19 Clinical Supervision and Professional Development of the Substance Abuse Counselor

Introduction

Clinical supervision is emerging as the crucible in which counselors acquire knowledge and skills for the substance abuse treatment profession, providing a bridge between the classroom and the clinic. Supervision is necessary in the substance abuse treatment field to improve client care, develop the professionalism of clinical personnel, and impart and maintain ethical standards in the field. In recent years, especially in the substance abuse field, clinical supervision has become the cornerstone of quality improvement and assurance.

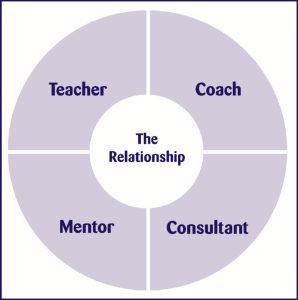

Your role and skill set as a clinical supervisor are distinct from those of counselor and administrator. Quality clinical supervision is founded on a positive supervisor–supervisee relationship that promotes client welfare and the professional development of the supervisee. You are a teacher, coach, consultant, mentor, evaluator, and administrator; you provide support, encouragement, and education to staff while addressing an array of psychological, interpersonal, physical, and spiritual issues of clients. Ultimately, effective clinical supervision ensures that clients are competently served. Supervision ensures that counselors continue to increase their skills, which in turn increases treatment effectiveness, client retention, and staff satisfaction. The clinical supervisor also serves as liaison between administrative and clinical staff.

This TIP focuses primarily on the teaching, coaching, consulting, and mentoring functions of clinical supervisors. Supervision, like substance abuse counseling, is a profession in its own right, with its own theories, practices, and standards. The profession requires knowledgeable, competent, and skillful individuals who are appropriately credentialed both as counselors and supervisors.

Definitions

This document builds on and makes frequent reference to CSAT’s Technical Assistance Publication (TAP), Competencies for Substance Abuse Treatment Clinical Supervisors (TAP 21-A; CSAT, 2007). The clinical supervision competencies identify those responsibilities and activities that define the work of the clinical supervisor. This TIP provides guidelines and tools for the effective delivery of clinical supervision in substance abuse treatment settings. TAP 21-A is a companion volume to TAP 21, Addiction Counseling Competencies (CSAT, 2006), which is another useful tool in supervision.

The perspective of this TIP is informed by the following two definitions of supervision:

- “Supervision is a disciplined, tutorial process wherein principles are transformed into practical skills, with four overlapping foci: administrative, evaluative, clinical, and supportive” (Powell & Brodsky, 2004, p. 11). “Supervision is an intervention provided by a senior member of a profession to a more junior member or members. … This relationship is evaluative, extends over time, and has the simultaneous purposes of enhancing the professional functioning of the more junior person(s); monitoring the quality of professional services offered to the clients that she, he, or they see; and serving as a gatekeeper of those who are to enter the particular profession” (Bernard & Goodyear, 2004, p. 8).

- Supervision is “a social influence process that occurs over time, in which the supervisor participates with supervisees to ensure quality of clinical care. Effective supervisors observe, mentor, coach, evaluate, inspire, and create an atmosphere that promotes self-motivation, learning, and professional development. They build teams, create cohesion, resolve conflict, and shape agency culture, while attending to ethical and diversity issues in all aspects of the process. Such supervision is key to both quality improvement and the successful implementation of consensus- and evidence-based practices” (CSAT, 2007, p. 3).

Rationale

For hundreds of years, many professions have relied on more senior colleagues to guide less experienced professionals in their crafts. This is a new development in the substance abuse field, as clinical supervision was only recently acknowledged as a discrete process with its own concepts and approaches.

As a supervisor to the client, counselor, and organization, the significance of your position is apparent in the following statements:

- Organizations have an obligation to ensure quality care and quality improvement of all personnel. The first aim of clinical supervision is to ensure quality services and to protect the welfare of clients.

- Supervision is the right of all employees and has a direct impact on workforce development and staff and client retention.

- You oversee the clinical functions of staff and have a legal and ethical responsibility to ensure quality care to clients, the professional development of counselors, and maintenance of program policies and procedures.

- Clinical supervision is how counselors in the field learn. In concert with classroom education, clinical skills are acquired through practice, observation, feedback, and implementation of the recommendations derived from clinical supervision.

Functions of a Clinical Supervisor

You, the clinical supervisor, wear several important “hats.” You facilitate the integration of counselor self-awareness, theoretical grounding, and development of clinical knowledge and skills; and you improve functional skills and professional practices. These roles often overlap and are fluid within the context of the supervisory relationship. Hence, the supervisor is in a unique position as an advocate for the agency, the counselor, and the client. You are the primary link between administration and front line staff, interpreting and monitoring compliance with agency goals, policies, and procedures and communicating staff and client needs to administrators. Central to the supervisor’s function is the alliance between the supervisor and supervisee (Rigazio-DiGilio, 1997).

As shown in Figure 19.1, your roles as a clinical supervisor in the context of the supervisory relationship include:

-

Teacher: Assist in the development of counseling knowledge and skills by identifying learning needs, determining counselor strengths, promoting self-awareness, and transmitting knowledge for practical use and professional growth. Supervisors are teachers, trainers, and professional role models.

-

Consultant: Bernard and Goodyear (2004) incorporate the supervisory consulting role of case consultation and review, monitoring performance, counseling the counselor regarding job performance, and assessing counselors. In this role, supervisors also provide alternative case conceptualizations, oversight of counselor work to achieve mutually agreed upon goals, and professional gatekeeping for the organization and discipline (e.g., recognizing and addressing counselor impairment).

-

Coach: In this supportive role, supervisors provide morale building, assess strengths and needs, suggest varying clinical approaches, model, cheerlead, and prevent burnout. For entry-level counselors, the supportive function is critical.

-

Mentor/Role Model: The experienced supervisor mentors and teaches the supervisee through role modeling, facilitates the counselor’s overall professional development and sense of professional identity, and trains the next generation of supervisors.

Central Principles of Clinical Supervision

The Consensus Panel for this TIP has identified central principles of clinical supervision. Although the Panel recognizes that clinical supervision can initially be a costly undertaking for many financially strapped programs, the Panel believes that ultimately clinical supervision is a cost-saving process. Clinical supervision enhances the quality of client care; improves efficiency of counselors in direct and indirect services; increases workforce satisfaction, professionalization, and retention; and ensures that services provided to the public uphold legal mandates and ethical standards of the profession.

The central principles identified by the Consensus Panel are:

- Clinical supervision is an essential part of all clinical programs.Clinical supervision is a central organizing activity that integrates the program mission, goals, and treatment philosophy with clinical theory and evidence-based practices (EBPs). The primary reasons for clinical supervision are to ensure (1) quality client care, and (2) clinical staff continue professional development in a systematic and planned manner. In substance abuse treatment, clinical supervision is the primary means of determining the quality of care provided.

- Clinical supervision enhances staff retention and morale. Staff turnover and workforce development are major concerns in the substance abuse treatment field. Clinical supervision is a primary means of improving workforce retention and job satisfaction (see, for example, Roche, Todd, & O’Connor, 2007).

- Every clinician, regardless of level of skill and experience, needs and has a right to clinical supervision. In addition, supervisors need and have a right to supervision of their supervision. Supervision needs to be tailored to the knowledge base, skills, experience, and assignment of each counselor. All staff need supervision, but the frequency and intensity of the oversight and training will depend on the role, skill level, and competence of the individual. The benefits that come with years of experience are enhanced by quality clinical supervision.

- Clinical supervision needs the full support of agency administrators.Just as treatment programs want clients to be in an atmosphere of growth and openness to new ideas, counselors should be in an environment where learning and professional development and opportunities are valued and provided for all staff.

- The supervisory relationship is the crucible in which ethical practice is developed and reinforced. The supervisor needs to model sound ethical and legal practice in the supervisory relationship. This is where issues of ethical practice arise and can be addressed. This is where ethical practice is translated from a concept to a set of behaviors. Through supervision, clinicians can develop a process of ethical decision-making and use this process as they encounter new situations.

- Clinical supervision is a skill in and of itself that has to be developed. Good counselors tend to be promoted into supervisory positions with the assumption that they have the requisite skills to provide professional clinical supervision. However, clinical supervisors need a different role orientation toward both program and client goals and a knowledge base to complement a new set of skills. Programs need to increase their capacity to develop good supervisors.

- Clinical supervision in substance abuse treatment most often requires balancing administrative and clinical supervision tasks. Sometimes these roles are complementary and sometimes they conflict. Often the supervisor feels caught between the two roles. Administrators need to support the integration and differentiation of the roles to promote the efficacy of the clinical supervisor.

- Culture and other contextual variables influence the supervision process; supervisors need to continually strive for cultural competence. Supervisors require cultural competence at several levels. Cultural competence involves the counselor’s response to clients, the supervisor’s response to counselors, and the program’s response to the cultural needs of the diverse community it serves. Since supervisors are in a position to serve as catalysts for change, they need to develop proficiency in addressing the needs of diverse clients and personnel.

- Successful implementation of EBPs requires ongoing supervision. Supervisors have a role in determining which specific EBPs are relevant for an organization’s clients (Lindbloom, Ten Eyck, & Gallon, 2005). Supervisors ensure that EBPs are successfully integrated into ongoing programmatic activities by training, encouraging, and monitoring counselors. Excellence in clinical supervision should provide greater adherence to the EBP model. Because state funding agencies now often require substance abuse treatment organizations to provide EBPs, supervision becomes even more important.

- Supervisors have the responsibility to be gatekeepers for the profession. Supervisors are responsible for maintaining professional standards, recognizing and addressing impairment, and safeguarding the welfare of clients. More than anyone else in an agency, supervisors can observe counselor behavior and respond promptly to potential problems, including counseling some individuals out of the field because they are ill-suited to the profession. This “gatekeeping” function is especially important for supervisors who act as field evaluators for practicum students prior to their entering the profession. Finally, supervisors also fulfill a gatekeeper role in performance evaluation and in providing formal recommendations to training institutions and credentialing bodies.

- Clinical supervision should involve direct observation methods. Direct observation should be the standard in the field because it is one of the most effective ways of building skills, monitoring counselor performance, and ensuring quality care. Supervisors require training in methods of direct observation, and administrators need to provide resources for implementing direct observation. Although small substance abuse agencies might not have the resources for one-way mirrors or videotaping equipment, other direct observation methods can be employed (see the section on methods of observation, below).

Guidelines for New Supervisors

Congratulations on your appointment as a supervisor! By now you might be asking yourself a few questions: What have I done? Was this a good career decision? There are many changes ahead. If you have been promoted from within, you’ll encounter even more hurdles and issues. First, it is important to face that your life has changed. You might experience the loss of friendship of peers. You might feel that you knew what to do as a counselor, but feel totally lost with your new responsibilities. You might feel less effective in your new role. Supervision can be an emotionally draining experience, as you now have to work with more staff-related interpersonal and human resources issues.

Before your promotion to clinical supervisor, you might have felt confidence in your clinical skills. Now you might feel unprepared and wonder if you need a training course for your new role. If you feel this way, you’re right. Although you are a good counselor, you do not necessarily possess all the skills needed to be a good supervisor. Your new role requires a new body of knowledge and different skills, along with the ability to use your clinical skills in a different way. Be confident that you will acquire these skills over time and that you made the right decision to accept your new position.

Suggestions for new supervisors:

- Quickly learn the organization’s policies and procedures and human resources procedures (e.g., hiring and firing, affirmative action requirements, format for conducting meetings, giving feedback, and making evaluations). Seek out this information as soon as possible through the human resources department or other resources within the organization.

- Ask for a period of 3 months to allow you to learn about your new role. During this period, do not make any changes in policies and procedures but use this time to find your managerial voice and decision-making style.

- Take time to learn about your supervisees, their career goals, interests, developmental objectives, and perceived strengths.

- Work to establish a contractual relationship with supervisees, with clear goals and methods of supervision.

- Learn methods to help staff reduce stress, address competing priorities, resolve staff conflict, and other interpersonal issues in the workplace.

- Obtain training in supervisory procedures and methods.

- Find a mentor, either internal or external to the organization.

- Shadow a supervisor you respect who can help you learn the ropes of your new job.

- Ask often and as many people as possible, “How am I doing?” and “How can I improve my performance as a clinical supervisor?”

- Ask for regular, weekly meetings with your administrator for training and instruction.

- Seek supervision of your supervision.

Problems and Resources

As a supervisor, you may encounter a broad array of issues and concerns, ranging from working within a system that does not fully support clinical supervision to working with resistant staff. A comment often heard in supervision training sessions is “My boss should be here to learn what is expected in supervision,” or “This will never work in my agency’s bureaucracy. They only support billable activities.” The work setting is where you apply the principles and practices of supervision and where organizations are driven by demands, such as financial solvency, profit, census, accreditation, and concerns over litigation. Therefore, you will need to be practical when beginning your new role as a supervisor: determine how you can make this work within your unique work environment.

Working With Staff Who Are Resistant to Supervision

Some of your supervisees may have been in the field longer than you have and see no need for supervision. Other counselors, having completed their graduate training, do not believe they need further supervision, especially not from a supervisor who might have less formal academic education than they have. Other resistance might come from ageism, sexism, racism, or classism. Particular to the field of substance abuse treatment may be the tension between those who believe that recovery from substance abuse is necessary for this counseling work and those who do not believe this to be true.

In addressing resistance, you must be clear regarding what your supervision program entails and must consistently communicate your goals and expectations to staff. To resolve defensiveness and engage your supervisees, you must also honor the resistance and acknowledge their concerns. Abandon trying to push the supervisee too far, too fast. Resistance is an expression of ambivalence about change and not a personality defect of the counselor. Instead of arguing with or exhorting staff, sympathize with their concerns, saying, “I understand this is difficult. How are we going to resolve these issues?”

When counselors respond defensively or reject directions from you, try to understand the origins of their defensiveness and to address their resistance. Self-disclosure by the supervisor about experiences as a supervisee, when appropriately used, may be helpful in dealing with defensive, anxious, fearful, or resistant staff. Work to establish a healthy, positive supervisory alliance with staff. Because many substance abuse counselors have not been exposed to clinical supervision, you may need to train and orient the staff to the concept and why it is important for your agency.

Things a New Supervisor Should Know

Eight truths a beginning supervisor should commit to memory are listed below:

- The reason for supervision is to ensure quality client care. As stated throughout this TIP, the primary goal of clinical supervision is to protect the welfare of the client and ensure the integrity of clinical services.>

- Supervision is all about the relationship. As in counseling, developing the alliance between the counselor and the supervisor is the key to good supervision.

- Culture and ethics influence all supervisory interactions. Contextual factors, culture, race, and ethnicity all affect the nature of the supervisory relationship. Some models of supervision (e.g., Holloway, 1995) have been built primarily around the role of context and culture in shaping supervision.

- Be human and have a sense of humor. As role models, you need to show that everyone makes mistakes and can admit to and learn from these mistakes.

- Rely first on direct observation of your counselors and give specific feedback. The best way to determine a counselor’s skills is to observe him or her and to receive input from the clients about their perceptions of the counseling relationship.

- Have and practice a model of counseling and of supervision; have a sense of purpose. Before you can teach a supervisee knowledge and skills, you must first know the philosophical and theoretical foundations on which you, as a supervisor, stand. Counselors need to know what they are going to learn from you, based on your model of counseling and supervision.

- Make time to take care of yourself spiritually, emotionally, mentally, and physically. Again, as role models, counselors are watching your behavior. Do you “walk the talk” of self-care?

- You have a unique position as an advocate for the agency, the counselor, and the client. As a supervisor, you have a wonderful opportunity to assist in the skill and professional development of your staff, advocating for the best interests of the supervisee, the client, and your organization.

Models of Clinical Supervision

You may never have thought about your model of supervision. However, it is a fundamental premise of this TIP that you need to work from a defined model of supervision and have a sense of purpose in your oversight role. Four supervisory orientations seem particularly relevant. They include:

- Competency-based models.

- Treatment-based models.

- Developmental approaches.

- Integrated models.

Competency-based models (e.g., microtraining, the Discrimination Model [Bernard & Goodyear, 2004], and the Task-Oriented Model [Mead, 1990], focus primarily on the skills and learning needs of the supervisee and on setting goals that are specific, measurable, attainable, realistic, and timely (SMART). They construct and implement strategies to accomplish these goals. The key strategies of competency-based models include applying social learning principles (e.g., modeling role reversal, role playing, and practice), using demonstrations, and using various supervisory functions (teaching, consulting, and counseling).

Treatment-based supervision models train to a particular theoretical approach to counseling, incorporating EBPs into supervision and seeking fidelity and adaptation to the theoretical model. Motivational interviewing, cognitive–behavioral therapy, and psychodynamic psychotherapy are three examples. These models emphasize the counselor’s strengths, seek the supervisee’s understanding of the theory and model taught, and incorporate the approaches and techniques of the model. The majority of these models begin with articulating their treatment approach and describing their supervision model, based upon that approach.

Developmental models, such as Stoltenberg and Delworth (1987), understand that each counselor goes through different stages of development and recognize that movement through these stages is not always linear and can be affected by changes in assignment, setting, and population served. (The developmental stages of counselors and supervisors are described in detail below).

Integrated models, including the Blended Model, begin with the style of leadership and articulate a model of treatment, incorporate descriptive dimensions of supervision (see below), and address contextual and developmental dimensions into supervision. They address both skill and competency development and affective issues, based on the unique needs of the supervisee and supervisor. Finally, integrated models seek to incorporate EBPs into counseling and supervision.

In all models of supervision, it is helpful to identify culturally or contextually centered models or approaches and find ways of tailoring the models to specific cultural and diversity factors. Issues to consider are:

- Explicitly addressing diversity of supervisees (e.g., race, ethnicity, gender, age, sexual orientation) and the specific factors associated with these types of diversity;

- Explicitly involving supervisees’ concerns related to particular client diversity (e.g., those whose culture, gender, sexual orientation, and other attributes differ from those of the supervisee) and addressing specific factors associated with these types of diversity; and

- Explicitly addressing supervisees’ issues related to effectively navigating services in intercultural communities and effectively networking with agencies and institutions.

It is important to identify your model of counseling and your beliefs about change, and to articulate a workable approach to supervision that fits the model of counseling you use. Theories are conceptual frameworks that enable you to make sense of and organize your counseling and supervision and to focus on the most salient aspects of a counselor’s practice. You may find some of the questions below to be relevant to both supervision and counseling. The answers to these questions influence both how you supervise and how the counselors you supervise work:

- What are your beliefs about how people change in both treatment and clinical supervision?

- What factors are important in treatment and clinical supervision?

- What universal principles apply in supervision and counseling and which are unique to clinical supervision?

- What conceptual frameworks of counseling do you use (for instance, cognitive–behavioral therapy, 12-Step facilitation, psychodynamic, behavioral)?

- What are the key variables that affect outcomes? (Campbell, 2000)

According to Bernard and Goodyear (2004) and Powell and Brodsky (2004), the qualities of a good model of clinical supervision are:

- Rooted in the individual, beginning with the supervisor’s self, style, and approach to leadership

- Precise, clear, and consistent.

- Comprehensive, using current scientific and evidence-based practices.

- Operational and practical, providing specific concepts and practices in clear, useful, and measurable terms.

- Outcome-oriented to improve counselor competence; make work manageable; create a sense of mastery and growth for the counselor; and address the needs of the organization, the supervisor, the supervisee, and the client.

Finally, it is imperative to recognize that, whatever model you adopt, it needs to be rooted in the learning and developmental needs of the supervisee, the specific needs of the clients they serve, the goals of the agency in which you work, and in the ethical and legal boundaries of practice. These four variables define the context in which effective supervision can take place.

Developmental Stages of Counselors

Counselors are at different stages of professional development. Thus, regardless of the model of supervision you choose, you must take into account the supervisee’s level of training, experience, and proficiency. Different supervisory approaches are appropriate for counselors at different stages of development. An understanding of the supervisee’s (and supervisor’s) developmental needs is an essential ingredient for any model of supervision.

Various paradigms or classifications of developmental stages of clinicians have been developed (Ivey, 1997; Rigazio-DiGilio, 1997; Skolvolt & Ronnestrand, 1992; Todd and Storn, 1997). This TIP has adopted the Integrated Developmental Model (IDM) of Stoltenberg, McNeill, and Delworth (1998). This schema uses a three-stage approach. The three stages of development have different characteristics and appropriate supervisory methods. Further application of the IDM to the substance abuse field is needed. (For additional information, see Anderson, 2001.)

| Developmental Level | Characteristics | Supervision Skills Development Needs | Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 |

|

|

|

| Level 2 |

|

|

|

| Level 3 |

|

|

|

| Source: Stoltenberg, Delworth, & McNeil, 1998 |

It is important to keep in mind several general cautions and principles about counselor development, including:

- There is a beginning but not an end point for learning clinical skills; be careful of counselors who think they “know it all.”

- Take into account the individual learning styles and personalities of your supervisees and fit the supervisory approach to the developmental stage of each counselor.

- There is a logical sequence to development, although it is not always predictable or rigid; some counselors may have been in the field for years, but remain at an early stage of professional development, whereas others may progress quickly through the stages.

- Counselors at an advanced developmental level have different learning needs and require different supervisory approaches from those at Level 1; and

- The developmental level can be applied for different aspects of a counselor’s overall competence (e.g., Level 2 mastery for individual counseling and Level 1 for couples counseling).

Developmental Stages of Supervisors

Just as counselors go through stages of development, so do supervisors. The developmental model presented in figure 19.3 provides a framework to explain why supervisors act as they do, depending on their developmental stage. It would be expected that someone new to supervision would be at a Level 1 as a supervisor. However, supervisors should be at least at the second or third stage of counselor development. If a newly appointed supervisor is still at Level 1 as a counselor, he or she will have little to offer to more seasoned supervisees.

| Developmental Level | Characteristics | To Increase Supervision Competence |

|---|---|---|

| Level 1 |

|

|

| Level 2 |

|

|

| Level 3 |

|

|

Cultural and Contextual Factors

Culture is one of the major contextual factors that influence supervisory interactions. Other contextual variables include race, ethnicity, age, gender, discipline, academic background, religious and spiritual practices, sexual orientation, disability, and recovery versus non-recovery status. The relevant variables in the supervisory relationship occur in the context of the supervisor, supervisee, client, and the setting in which supervision occurs. More care should be taken to:

- Identify the competencies necessary for substance abuse counselors to work with diverse individuals and navigate intercultural communities.

- Identify methods for supervisors to assist counselors in developing these competencies.

- Provide evaluation criteria for supervisors to determine whether their supervisees have met minimal competency standards for effective and relevant practice.

Models of supervision have been strongly influenced by contextual variables and their influence on the supervisory relationship and process, such as Holloway’s Systems Model (1995) and Constantine’s Multicultural Model (2003).

The competencies listed in TAP 21-A reflect the importance of culture in supervision (CSAT, 2007). The Counselor Development domain encourages self-examination of attitudes toward culture and other contextual variables. The Supervisory Alliance domain promotes attention to these variables in the supervisory relationship. (See also the TIP, Improving Cultural Competence in Substance Abuse Counseling [CSAT, 2014].)

Cultural competence “refers to the ability to honor and respect the beliefs, language, interpersonal styles, and behaviors of individuals and families receiving services, as well as staff who are providing such services. Cultural competence is a dynamic, ongoing, developmental process that requires a commitment and is achieved over time” (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2003, p. 12). Culture shapes belief systems, particularly concerning issues related to mental health and substance abuse, as well as the manifestation of symptoms, relational styles, and coping patterns.

There are three levels of cultural consideration for the supervisory process: the issue of the culture of the client being served and the culture of the counselor in supervision. Holloway (1995) emphasizes the cultural issues of the agency, the geographic environment of the organization, and many other contextual factors. Specifically, there are three important areas in which cultural and contextual factors play a key role in supervision: in building the supervisory relationship or working alliance, in addressing the specific needs of the client, and in building supervisee competence and ability. It is your responsibility to address your supervisees’ beliefs, attitudes, and biases about cultural and contextual variables to advance their professional development and promote quality client care.

Becoming culturally competent and able to integrate other contextual variables into supervision is a complex, long-term process. Cross (1989) has identified several stages on a continuum of becoming culturally competent (see figure 19.4).

Figure 19.4. Continuum of Cultural Competence

Cultural Destructiveness

Superiority of dominant culture and inferiority of other cultures; active discrimination

Cultural Incapacity

Separate but equal treatment; passive discrimination

Cultural Blindness

Sees all cultures and people as alike and equal; discrimination by ignoring culture

Cultural Openness (Sensitivity)

Basic understanding and appreciation of importance of sociocultural factors in work with minority populations

Cultural Competence

Capacity to work with more complex issues and cultural nuances

Cultural Proficiency

Highest capacity for work with minority populations; a commitment to excellence and proactive effort

Source: Cross, 1989.

Although you may never have had specialized training in multicultural counseling, some of your supervisees may have (see Constantine, 2003). Regardless, it is your responsibility to help supervisees build on the cultural competence skills they possess as well as to focus on their cultural competence deficits. It is important to initiate discussion of issues of culture, race, gender, sexual orientation, and the like in supervision to model the kinds of discussion you would like counselors to have with their clients. If these issues are not addressed in supervision, counselors may come to believe that it is inappropriate to discuss them with clients and have no idea how such dialog might proceed. These discussions prevent misunderstandings with supervisees based on cultural or other factors. Another benefit from these discussions is that counselors will eventually achieve some level of comfort in talking about culture, race, ethnicity, and diversity issues.

If you haven’t done it as a counselor, early in your tenure as a supervisor you will want to examine your culturally influenced values, attitudes, experiences, and practices and to consider what effects they have on your dealings with supervisees and clients. Counselors should undergo a similar review as preparation for when they have clients of a culture different from their own. Some questions to keep in mind are:

- What did you think when you saw the supervisee’s last name?

- What did you think when the supervisee said his or her culture is X, when yours is Y?

- How did you feel about this difference?

- What did you do in response to this difference?

Constantine (2003) suggests that supervisors can use the following questions with supervisees:

- What demographic variables do you use to identify yourself?

- What worldviews (e.g., values, assumptions, and biases) do you bring to supervision based on your cultural identities?

- What struggles and challenges have you faced working with clients who were from different cultures than your own?

Beyond self-examination, supervisors will want continuing education classes, workshops, and conferences that address cultural competence and other contextual factors. Community resources, such as community leaders, elders, and healers, can contribute to your understanding of the culture your organization serves. Finally, supervisors (and counselors) should participate in multicultural activities, such as community events, discussion groups, religious festivals, and other ceremonies.

The supervisory relationship includes an inherent power differential, and it is important to pay attention to this disparity, particularly when the supervisee and the supervisor are from different cultural groups. A potential for the misuse of that power exists at all times but especially when working with supervisees and clients within multicultural contexts. When the supervisee is from a minority population and the supervisor is from a majority population, the differential can be exaggerated. You will want to prevent institutional discrimination from affecting the quality of supervision. The same is true when the supervisee is gay and the supervisor is heterosexual, or the counselor is non-degreed and the supervisor has an advanced degree, or a female supervisee with a male supervisor, and so on. In the reverse situations, where the supervisor is from the minority group and the supervisee from the majority group, the difference should be discussed as well.

Ethical and Legal Issues

You are the organization’s gatekeeper for ethical and legal issues. First, you are responsible for upholding the highest standards of ethical, legal, and moral practices and for serving as a model of practice to staff. Further, you should be aware of and respond to ethical concerns. Part of your job is to help integrate solutions to everyday legal and ethical issues into clinical practice.

Some of the underlying assumptions of incorporating ethical issues into clinical supervision include:

- Ethical decision-making is a continuous, active process.

- Ethical standards are not a cookbook. They tell you what to do, not always how.

- Each situation is unique. Therefore, it is imperative that all personnel learn how to “think ethically” and how to make sound legal and ethical decisions.

- The most complex ethical issues arise in the context of two ethical behaviors that conflict; for instance, when a counselor wants to respect the privacy and confidentiality of a client, but it is in the client’s best interest for the counselor to contact someone else about his or her care.

- Therapy is conducted by fallible beings; people make mistakes—hopefully, minor ones.

- Sometimes the answers to ethical and legal questions are elusive. Ask a dozen people, and you’ll likely get twelve different points of view.

Helpful resources on legal and ethical issues for supervisors include Beauchamp and Childress (2001); Falvey (2002b); Gutheil and Brodsky (2008); Pope, Sonne, and Greene (2006); and Reamer (2006).

Legal and ethical issues that are critical to clinical supervisors include (1) vicarious liability (or respondeat superior), (2) dual relationships and boundary concerns, (4) informed consent, (5) confidentiality, and (6) supervisor ethics.

Direct Versus Vicarious Liability

An important distinction needs to be made between direct and vicarious liability. Direct liability of the supervisor might include dereliction of supervisory responsibility, such as “not making a reasonable effort to supervise” (defined below).

In vicarious liability, a supervisor can be held liable for damages incurred as a result of negligence in the supervision process. Examples of negligence include providing inappropriate advice to a counselor about a client (for instance, discouraging a counselor from conducting a suicide screen on a depressed client), failure to listen carefully to a supervisee’s comments about a client, and the assignment of clinical tasks to inadequately trained counselors. The key legal question is: “Did the supervisor conduct him- or herself in a way that would be reasonable for someone in his position?” or “Did the supervisor make a reasonable effort to supervise?” A generally accepted time standard for a “reasonable effort to supervise” in the behavioral health field is 1 hour of supervision for every 20–40 hours of clinical services. Of course, other variables (such as the quality and content of clinical supervision sessions) also play a role in a reasonable effort to supervise.

Supervisory vulnerability increases when the counselor has been assigned too many clients, when there is no direct observation of a counselor’s clinical work, when staff are inexperienced or poorly trained for assigned tasks, and when a supervisor is not involved or not available to aid the clinical staff. In legal texts, vicarious liability is referred to as “respondeat superior.”

Dual Relationships and Boundary Issues

Dual relationships can occur at two levels: between supervisors and supervisees and between counselors and clients. You have a mandate to help your supervisees recognize and manage boundary issues. A dual relationship occurs in supervision when a supervisor has a primary professional role with a supervisee and, at an earlier time, simultaneously or later, engages in another relationship with the supervisee that transcends the professional relationship. Examples of dual relationships in supervision include providing therapy for a current or former supervisee, developing an emotional relationship with a supervisee or former supervisee, and becoming an Alcoholics Anonymous sponsor for a former supervisee. Obviously, there are varying degrees of harm or potential harm that might occur as a result of dual relationships, and some negative effects of dual relationships might not be apparent until later.

Therefore, firm, always-or-never rules aren’t applicable. You have the responsibility of weighing with the counselor the anticipated and unanticipated effects of dual relationships, helping the supervisee’s self-reflective awareness when boundaries become blurred, when he or she is getting close to a dual relationship, or when he or she is crossing the line in the clinical relationship.

Exploring dual relationship issues with counselors in clinical supervision can raise its own professional dilemmas. For instance, clinical supervision involves unequal status, power, and expertise between a supervisor and supervisee. Being the evaluator of a counselor’s performance and gatekeeper for training programs or credentialing bodies also might involve a dual relationship. Further, supervision can have therapy-like qualities as you explore countertransferential issues with supervisees, and there is an expectation of professional growth and self-exploration. What makes a dual relationship unethical in supervision is the abusive use of power by either party, the likelihood that the relationship will impair or injure the supervisor’s or supervisee’s judgment, and the risk of exploitation.

The most common basis for legal action against counselors (20 percent of claims) and the most frequently heard complaint by certification boards against counselors (35 percent) is some form of boundary violation or sexual impropriety (Falvey, 2002b).

Codes of ethics for most professions clearly advise that dual relationships between counselors and clients should be avoided. Dual relationships between counselors and supervisors are also a concern and are addressed in the substance abuse counselor codes and those of other professions as well. Problematic dual relationships between supervisees and supervisors might include intimate relationships (sexual and non-sexual) and therapeutic relationships, wherein the supervisor becomes the counselor’s therapist. Sexual involvement between the supervisor and supervisee can include sexual attraction, harassment, consensual (but hidden) sexual relationships, or intimate romantic relationships. Other common boundary issues include asking the supervisee to do favors, providing preferential treatment, socializing outside the work setting, and using emotional abuse to enforce power.

It is imperative that all parties understand what constitutes a dual relationship between supervisor and supervisee and avoid these dual relationships. Sexual relationships between supervisors and supervisees and counselors and clients occur far more frequently than one might realize (Falvey, 2002b). In many states, they constitute a legal transgression as well as an ethical violation.

Informed Consent

Informed consent is key to protecting the counselor and/or supervisor from legal concerns, requiring the recipient of any service or intervention to be sufficiently aware of what is to happen, and of the potential risks and alternative approaches, so that the person can make an informed and intelligent decision about participating in that service. The supervisor must inform the supervisee about the process of supervision, the feedback and evaluation criteria, and other expectations of supervision. The supervision contract should clearly spell out these issues. Supervisors must ensure that the supervisee has informed the client about the parameters of counseling and supervision (such as the use of live observation or video- or audiotaping). A sample template for informed consent is provided in Part 2, chapter 2 (p. 106).

Confidentiality

In supervision, regardless of whether there is a written or verbal contract between the supervisor and supervisee, there is an implied contract and duty of care because of the supervisor’s vicarious liability. Informed consent and concerns for confidentiality should occur at three levels: client consent to treatment, client consent to supervision of the case, and supervisee consent to supervision (Bernard & Goodyear, 2004). In addition, there is an implied consent and commitment to confidentiality by supervisors to assume their supervisory responsibilities and institutional consent to comply with legal and ethical parameters of supervision. (See also the Code of Ethics of the Association for Counselor Education and Supervision [ACES], available online at http://www.acesonline.net/members/supervision/.)

With informed consent and confidentiality comes a duty not to disclose certain relational communication. Limits of confidentiality of supervision session content should be stated in all organizational contracts with training institutions and credentialing bodies. Criteria for waiving client and supervisee privilege should be stated in institutional policies and discipline-specific codes of ethics and clarified by advice of legal counsel and the courts. Because standards of confidentiality are determined by state legal and legislative systems, it is prudent for supervisors to consult with an attorney to determine the state codes of confidentiality and clinical privileging.

In the substance abuse treatment field, confidentiality for clients is clearly defined by federal law: 42 CFR, Part 2 and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Key information is available at http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/. Supervisors need to train counselors in confidentiality regulations and to adequately document their supervision, including discussions and directives, especially relating to duty-to-warn situations. Supervisors need to ensure that counselors provide clients with appropriate duty-to-warn information early in the counseling process and inform clients of the limits of confidentiality as part of the agency’s informed consent procedures.

Under duty-to-warn requirements (e.g., child abuse, suicidal or homicidal ideation), supervisors need to be aware of and take action as soon as possible in situations in which confidentiality may need to be waived. Organizations should have a policy stating how clinical crises will be handled (Falvey, 2002b). What mechanisms are in place for responding to crises? In what timeframe will a supervisor be notified of a crisis situation? Supervisors must document all discussions with counselors concerning duty-to-warn and crises. At the onset of supervision, supervisors should ask counselors if there are any duty-to-warn issues of which the supervisor should be informed.

New technology brings new confidentiality concerns. Websites now dispense information about substance abuse treatment and provide counseling services. With the growth in online counseling and supervision, the following concerns emerge: (a) how to maintain confidentiality of information, (b) how to ensure the competence and qualifications of counselors providing online services, and (c) how to establish reporting requirements and duty to warn when services are conducted across State and international boundaries. New standards will need to be written to address these issues. (The National Board for Certified Counselors has guidelines for counseling by Internet at https://www.matrc.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/NBCC-Policy-Regarding-Practice-of-Distance-Professional-Services-2016.pdf.)

Supervisor Ethics

In general, supervisors adhere to the same standards and ethics as substance abuse counselors with regard to dual relationship and other boundary violations. Supervisors will:

- Uphold the highest professional standards of the field.

- Seek professional help (outside the work setting) when personal issues interfere with their clinical and/or supervisory functioning.

- Conduct themselves in a manner that models and sets an example for agency mission, vision, philosophy, wellness, recovery, and consumer satisfaction.

- Reinforce zero tolerance for interactions that are not professional, courteous, and compassionate.

- Treat supervisees, colleagues, peers, and clients with dignity, respect, and honesty.

- Adhere to the standards and regulations of confidentiality as dictated by the field. This applies to the supervisory as well as the counseling relationship.

Monitoring Performance

The goal of supervision is to ensure quality care for the client, which entails monitoring the clinical performance of staff. Your first step is to educate supervisees in what to expect from clinical supervision. Once the functions of supervision are clear, you should regularly evaluate the counselor’s progress in meeting organizational and clinical goals as set forth in an Individual Development Plan (IDP) (see the section on IDPs below). As clients have an individual treatment plan, counselors also need a plan to promote skill development.

Behavioral Contracting in Supervision

Among the first tasks in supervision is to establish a contract for supervision that outlines realistic accountability for both yourself and your supervisee. The contract should be in writing and should include the purpose, goals, and objectives of supervision; the context in which supervision is provided; ethical and institutional policies that guide supervision and clinical practices; the criteria and methods of evaluation and outcome measures; the duties and responsibilities of the supervisor and supervisee; procedural considerations (including the format for taping and opportunities for live observation); and the supervisee’s scope of practice and competence. The contract for supervision should state the rewards for fulfillment of the contract (such as clinical privileges or increased compensation), the length of supervision sessions, and sanctions for noncompliance by either the supervisee or supervisor. The agreement should be compatible with the developmental needs of the supervisee and address the obstacles to progress (lack of time, performance anxiety, resource limitations). Once a behavioral contract has been established, the next step is to develop an IDP.

Individual Development Plan

The IDP is a detailed plan for supervision that includes the goals that you and the counselor wish to address over a certain time period (perhaps 3 months). Each of you should sign and keep a copy of the IDP for your records. The goals are normally stated in terms of skills the counselor wishes to build or professional resources the counselor wishes to develop. These skills and resources are generally oriented to the counselor’s job in the program or activities that would help the counselor develop professionally. The IDP should specify the timelines for change, the observation methods that will be employed, expectations for the supervisee and the supervisor, the evaluation procedures that will be employed, and the activities that will be expected to improve knowledge and skills. An example of an IDP is provided in Part 2, chapter 2 (p. 122).

As a supervisor, you should have your own IDP, based on the supervisory competencies listed in TAP 21-A (CSAT, 2007), that addresses your training goals. This IDP can be developed in cooperation with your supervisor, or in external supervision, peer input, academic advisement, or mentorship.

Evaluation of Counselors

Supervision inherently involves evaluation, building on a collaborative relationship between you and the counselor. Evaluation may not be easy for some supervisors. Although everyone wants to know how they are doing, counselors are not always comfortable asking for feedback. And, as most supervisors prefer to be liked, you may have difficulty giving clear, concise, and accurate evaluations to staff.

The two types of evaluation are formative and summative. A formative evaluation is an ongoing status report of the counselor’s skill development, exploring the questions “Are we addressing the skills or competencies you want to focus on?” and “How do we assess your current knowledge and skills and areas for growth and development?”

Summative evaluation is a more formal rating of the counselor’s overall job performance, fitness for the job, and job rating. It answers the question, “How does the counselor measure up?” Typically, summative evaluations are done annually and focus on the counselor’s overall strengths, limitations, and areas for future improvement.

It should be acknowledged that supervision is inherently an unequal relationship. In most cases, the supervisor has positional power over the counselor. Therefore, it is important to establish clarity of purpose and a positive context for evaluation. Procedures should be spelled out in advance, and the evaluation process should be mutual, flexible, and continuous. The evaluation process inevitably brings up supervisee anxiety and defensiveness that need to be addressed openly. It is also important to note that each individual counselor will react differently to feedback; some will be more open to the process than others.

There has been considerable research on supervisory evaluation, with these findings:

- The supervisee’s confidence and efficacy are correlated with the quality and quantity of feedback the supervisor gives to the supervisee (Bernard & Goodyear, 2004).

- Ratings of skills are highly variable between supervisors, and often the supervisor’s and supervisee’s ratings differ or conflict (Eby, 2007).

- Good feedback is provided frequently, clearly, and consistently and is SMART (specific, measurable, attainable, realistic, and timely) (Powell & Brodsky, 2004).

Direct observation of the counselor’s work is the desired form of input for the supervisor. Although direct observation has historically been the exception in substance abuse counseling, ethical and legal considerations and evidence support that direct observation as preferable. The least desirable feedback is unannounced observation by supervisors followed by vague, perfunctory, indirect, or hurtful delivery (Powell & Brodsky, 2004).

Clients are often the best assessors of the skills of the counselor. Supervisors should routinely seek input from the clients as to the outcome of treatment. The method of seeking input should be discussed in the initial supervisory sessions and be part of the supervision contract. In a residential substance abuse treatment program, you might regularly meet with clients after sessions to discuss how they are doing, how effective the counseling is, and the quality of the therapeutic alliance with the counselor. (For examples of client satisfaction or input forms, search for Client-Directed Outcome-Informed Treatment and Training Materials at http://www.goodtherapy.org/client-directed-outcome-informed-therapy.html)

Before formative evaluations begin, methods of evaluating performance should be discussed, clarified in the initial sessions, and included in the initial contract so that there will be no surprises. Formative evaluations should focus on changeable behavior and, whenever possible, be separate from the overall annual performance appraisal process. To determine the counselor’s skill development, you should use written competency tools, direct observation, counselor self-assessments, client evaluations, work samples (files and charts), and peer assessments. Examples of work samples and peer assessments can be found in Bernard and Goodyear (2004), Powell and Brodsky (2004), and Campbell (2000). It is important to acknowledge that counselor evaluation is essentially a subjective process involving supervisors’ opinions of the counselors’ competence.

Addressing Burnout and Compassion Fatigue

Did you ever hear a counselor say, “I came into counseling for the right reasons. At first I loved seeing clients. But the longer I stay in the field, the harder it is to care. The joy seems to have gone out of my job. Should I get out of counseling as many of my colleagues are doing?” Most substance abuse counselors come into the field with a strong sense of calling and the desire to be of service to others, with a strong pull to use their gifts and make themselves instruments of service and healing. The substance abuse treatment field risks losing many skilled and compassionate healers when the life goes out of their work. Some counselors simply withdraw, care less, or get out of the field entirely. Most just complain or suffer in silence. Given the caring and dedication that brings counselors into the field, it is important for you to help them address their questions and doubts. (See Lambie, 2006, and Shoptaw, Stein, & Rawson, 2000.)

You can help counselors with self-care; help them look within; become resilient again; and rediscover what gives them joy, meaning, and hope in their work. Counselors need time for reflection, to listen again deeply and authentically. You can help them redevelop their innate capacity for compassion, to be an openhearted presence for others.

You can help counselors develop a life that does not revolve around work. This has to be supported by the organization’s culture and policies that allow for appropriate use of time off and self-care without punishment. Aid them by encouraging them to take earned leave and to take “mental health” days when they are feeling tired and burned out. Remind staff to spend time with family and friends, exercise, relax, read, or pursue other life-giving interests.

It is important for the clinical supervisor to normalize the counselor’s reactions to stress and compassion fatigue in the workplace as a natural part of being an empathic and compassionate person and not an individual failing or pathology. (See Burke, Carruth, & Prichard, 2006.)

Rest is good; self-care is important. Everyone needs times of relaxation and recreation. Often, a month after a refreshing vacation you lose whatever gain you made. Instead, longer-term gain comes from finding what brings you peace and joy. It is not enough for you to help counselors understand “how” to counsel, you can also help them with the “why.” Why are they in this field? What gives them meaning and purpose at work? When all is said and done, when counselors have seen their last client, how do they want to be remembered? What do they want said about them as counselors? Usually, counselors’ responses to this question are fairly simple: “I want to be thought of as a caring, compassionate person, a skilled helper.” These are important spiritual questions that you can discuss with your supervisees.

Other suggestions include:

- Help staff identify what is happening within the organization that might be contributing to their stress and learn how to address the situation in a way that is productive to the client, the counselor, and the organization.

- Get training in identifying the signs of primary stress reactions, secondary trauma, compassion fatigue, vicarious traumatization, and burnout. Help staff match up self-care tools to specifically address each of these experiences.

- Support staff in advocating for organizational change when appropriate and feasible as part of your role as liaison between administration and clinical staff.

- Assist staff in adopting lifestyle changes to increase their emotional resilience by reconnecting to their world (family, friends, sponsors, mentors), spending time alone for self-reflection, and forming habits that re-energize them.

- Help them eliminate the “what ifs” and negative self-talk. Help them let go of their idealism that they can save the world.

- If possible in the current work environment, set parameters on their work by helping them adhere to scheduled time off, keep lunch time personal, set reasonable deadlines for work completion, and keep work away from personal time.

- Teach and support generally positive work habits. Some counselors lack basic organizational, teamwork, phone, and time management skills (ending sessions on time and scheduling to allow for documentation). The development of these skills helps to reduce the daily wear that erodes well-being and contributes to burnout.

- Ask them, “When was the last time you had fun?” “When was the last time you felt fully alive?” Suggest they write a list of things about their job about which they are grateful. List five people they care about and love. List five accomplishments in their professional life. Ask, “Where do you want to be in your professional life in 5 years?”

You have a fiduciary responsibility given you by clients to ensure counselors are healthy and whole. It is your responsibility to aid counselors in addressing their fatigue and burnout.

Gatekeeping Functions

In monitoring counselor performance, an important and often difficult supervisory task is managing problem staff or those individuals who should not be counselors. This is the gatekeeping function. Part of the dilemma is that most likely you were first trained as a counselor, and your values lie within that domain. You were taught to acknowledge and work with individual limitations, always respecting the individual’s goals and needs. However, you also carry a responsibility to maintain the quality of the profession and to protect the welfare of clients. Thus, you are charged with the task of assessing the counselor for fitness for duty and have an obligation to uphold the standards of the profession.

Experience, credentials, and academic performance are not the same as clinical competence. In addition to technical counseling skills, many important therapeutic qualities affect the outcome of counseling, including insight, respect, genuineness, concreteness, and empathy. Research consistently demonstrates that personal characteristics of counselors are highly predictive of client outcome (Herman, 1993, Hubble, Duncan & Miller, 1999). The essential questions are: Who should or should not be a counselor? What behaviors or attitudes are unacceptable? How would a clinical supervisor address these issues in supervision?

Unacceptable behavior might include actions hurtful to the client, boundary violations with clients or program standards, illegal behavior, significant psychiatric impairment, consistent lack of self-awareness, inability to adhere to professional codes of ethics, or consistent demonstration of attitudes that are not conducive to work with clients in substance abuse treatment. You will want to have a model and policies and procedures in place when disciplinary action is undertaken with an impaired counselor. For example, progressive disciplinary policies clearly state the procedures to follow when impairment is identified. Consultation with the organization’s attorney and familiarity with state case law are important. It is advisable for the agency to be familiar with and have contact with your state impaired counselor organization, if it exists.

How impaired must a counselor be before disciplinary action is needed? Clear job descriptions and statements of scope of practice and competence are important when facing an impaired counselor. How tired or distressed can a counselor be before a supervisor takes the counselor off-line for these or similar reasons? You need administrative support with such interventions and to identify approaches to managing worn-out counselors. The Consensus Panel recommends that your organization have an employee assistance program (EAP) in place so you can refer staff outside the agency. It is also important for you to learn the distinction between a supervisory referral and a self-referral. Self-referral may include a recommendation by the supervisor, whereas a supervisory referral usually occurs with a job performance problem.

You will need to provide verbal and written evaluations of the counselor’s performance and actions to ensure that the staff member is aware of the behaviors that need to be addressed. Treat all supervisees the same, following agency procedures and timelines. Follow the organization’s progressive disciplinary steps and document carefully what is said, how the person responds, and what actions are recommended. You can discuss organizational issues or barriers to action with the supervisee (such as personnel policies that might be exacerbating the employee’s issues). Finally, it may be necessary for you to take the action that is in the best interest of the clients and the profession, which might involve counseling your supervisee out of the field.

Remember that the number one goal of a clinical supervisor is to protect the welfare of the client, which, at times, can mean enforcing the gatekeeping function of supervision.

Methods of Observation

It is important to observe counselors frequently over an extended period of time. Supervisors in the substance abuse treatment field have traditionally relied on indirect methods of supervision (process recordings, case notes, verbal reports by the supervisees, and verbatims). However, the Consensus Panel recommends that supervisors use direct observation of counselors through recording devices (such as video and audio taping) and live observation of counseling sessions, including one-way mirrors. Indirect methods have significant drawbacks, including:

- A counselor will recall a session as he or she experienced it. If a counselor experiences a session positively or negatively, the report to the supervisor will reflect that. The report is also affected by the counselor’s level of skill and experience.

- The counselor’s report is affected by his or her biases and distortions (both conscious and unconscious). The report does not provide a thorough sense of what really happened in the session because it relies too heavily on the counselor’s recall.

- Indirect methods include a time delay in reporting.

- The supervisee may withhold clinical information due to evaluation anxiety or naiveté.

Your understanding of the session will be improved by direct observation of the counselor. Direct observation is much easier today, as a variety of technological tools are available, including audio and videotaping, remote audio devices, interactive videos, live feeds, and even supervision through web-based cameras.

Guidelines that apply to all methods of direct observation in supervision include:

- Simply by observing a counseling session, the dynamics will change. You may change how both the client and counselor act. You get a snapshot of the sessions. Counselors will say, “it was not a representative session.” Typically, if you observe the counselor frequently, you will get a fairly accurate picture of the counselor’s competencies.

- You and your supervisee must agree on procedures for observation to determine why, when, and how direct methods of observation will be used.

- The counselor should provide a context for the session.

- The client should give written consent for observation and/or taping at intake, before beginning counseling. Clients must know all the conditions of their treatment before they consent to counseling. Additionally, clients need to be notified of an upcoming observation by a supervisor before the observation occurs.

- Observations should be selected for review (including a variety of sessions and clients, challenges, and successes) because they provide teaching moments. You should ask the supervisee to select what cases he or she wishes you to observe and explain why those cases were chosen. Direct observation should not be a weapon for criticism but a constructive tool for learning: an opportunity for the counselor to do things right and well, so that positive feedback follows.

- When observing a session, you gain a wealth of information about the counselor. Use this information wisely, and provide gradual feedback, not a litany of judgments and directives. Ask the salient question, “What is the most important issue here for us to address in supervision?”

- A supervisee might claim client resistance to direct observation, saying, “It will make the client nervous. The client does not want to be taped.” However, “client resistance” is more likely to be reported when the counselor is anxious about being taped. It is important for you to gently and respectfully address the supervisee’s resistance while maintaining the position that direct observation is an integral component of his or her supervision.

- Given the nature of the issues in drug and alcohol counseling, you and your supervisee need to be sensitive to increased client anxiety about direct observation because of the client’s fears about job or legal repercussions, legal actions, criminal behaviors, violence and abuse situations, and the like.

- Ideally, the supervisee should know at the outset of employment that observation and/or taping will be required as part of informed consent to supervision.

In instances where there is overwhelming anxiety regarding observation, you should pace the observation to reduce the anxiety, giving the counselor adequate time for preparation. Often enough, counselors will feel more comfortable with observation equipment (such as a video camera or recording device) rather than direct observation with the supervisor in the room.

The choice of observation methods in a particular situation will depend on the need for an accurate sense of counseling, the availability of equipment, the context in which the supervision is provided, and the counselor’s and your skill levels. A key factor in the choice of methods might be the resistance of the counselor to being observed. For some supervisors, direct observation also puts the supervisor’s skills on the line too, as they might be required to demonstrate or model their clinical competencies.

Recorded Observation

Audiotaped supervision has traditionally been a primary medium for supervisors and remains a vital resource for therapy models such as motivational interviewing. On the other hand, videotape supervision (VTS) is the primary method of direct observation in both the marriage and family therapy and social work fields (Munson, 1993; Nichols, Nichols, & Hardy, 1990). Video cameras are increasingly commonplace in professional settings. VTS is easy, accessible, and inexpensive. However, it is also a complex, powerful and dynamic tool, and one that can be challenging, threatening, anxiety-provoking, and humbling. Several issues related to VTS are unique to the substance abuse field:

- Many substance abuse counselors “grew up” in the field without taping and may be resistant to the medium;

- Many agencies operate on limited budgets and administrators may see the expensive equipment as prohibitive and unnecessary; and

- Many substance abuse supervisors have not been trained in the use of videotape equipment or in VTS.

Yet, VTS offers nearly unlimited potential for creative use in staff development. To that end, you need training in how to use VTS effectively. The following are guidelines for VTS:

- Clients must sign releases before taping. Most programs have a release form that the client signs on admission. The supervisee informs the client that videotaping will occur and reminds the client about the signed release form. The release should specify that the taping will be done exclusively for training purposes and will be reviewed only by the counselor, the supervisor, and other supervisees in group supervision. Permission will most likely be granted if the request is made in a sensitive and appropriate manner. It is critical to note that even if permission is initially given by the client, this permission can be withdrawn. You cannot force compliance.

- The use and rationale for taping needs to be clearly explained to clients. This will forestall a client’s questioning as to why a particular session is being taped.

- Risk-management considerations in today’s litigious climate necessitate that tapes be erased after the supervision session. Tapes can be admissible as evidence in court as part of the clinical record. Since all tapes should be erased after supervision, this must be stated in agency policies. If there are exceptions, those need to be described.

- Too often, supervisors watch long, uninterrupted segments of tape with little direction or purpose. To avoid this, you may want to ask your supervisee to cue the tape to the segment he or she wishes to address in supervision, focusing on the goals established in the IDP. Having said this, listening only to segments selected by the counselor can create some of the same disadvantages as self-report: the counselor chooses selectively, even if not consciously. The supervisor may occasionally choose to watch entire sessions.

- You need to evaluate session flow, pacing, and how counselors begin and end sessions.

Some clients may not be comfortable being videotaped but may be more comfortable with audio taping. Videotaping is not permitted in most prison settings and EAP services. Videotaping may not be advisable when treating patients with some diagnoses, such as paranoia or some schizophrenic illnesses. In such cases, either live observation or less intrusive measures, such as audio taping, may be preferred.

Live Observation

With live observation you actually sit in on a counseling session with the supervisee and observe the session first hand. The client will need to provide informed consent before being observed. Although one-way mirrors are not readily available at most agencies, they are an alternative to actually sitting in on the session. A videotape may also be used either from behind the one-way mirror (with someone else operating the videotaping equipment) or physically located in the counseling room, with the supervisor sitting in the session. This combination of mirror, videotaping, and live observation may be the best of all worlds, allowing for unobtrusive observation of a session, immediate feedback to the supervisee, modeling by the supervisor (if appropriate), and a record of the session for subsequent review in supervision. Live supervision may involve some intervention by the supervisor during the session.

Live observation is effective for the following reasons:

- It allows you to get a true picture of the counselor in action.

- It gives you an opportunity to model techniques during an actual session, thus serving as a role model for both the counselor and the client.

- Should a session become countertherapeutic, you can intervene for the well-being of the client.

- Counselors often say they feel supported when a supervisor joins the session, and clients periodically say, “This is great! I got two for the price of one.”

- It allows for specific and focused feedback.

- It is more efficient for understanding the counseling process.

- It helps connect the IDP to supervision.

To maximize the effectiveness of live observation, supervisors must stay primarily in an observer role so as to not usurp the leadership or undercut the credibility and authority of the counselor.

Live observation has some disadvantages:

- It is time consuming.

- It can be intrusive and alter the dynamics of the counseling session.

- It can be anxiety-provoking for all involved.

Some mandated clients may be particularly sensitive to live observation. This becomes essentially a clinical issue to be addressed by the counselor with the client. Where is this anxiety coming from, how does it relate to other anxieties and concerns, and how can it best be addressed in counseling?

Supervisors differ on where they should sit in a live observation session. Some suggest that the supervisor sit so as to not interrupt or be involved in the session. Others suggest that the supervisor sit in a position that allows for inclusion in the counseling process.

Here are some guidelines for conducting live observation:

- The counselor should always begin with informed consent to remind the client about confidentiality. Periodically, the counselor should begin the session with a statement of confidentiality, reiterating the limits of confidentiality and the duty to warn, to ensure that the client is reminded of what is reportable by the supervisor and/or counselor.

- While sitting outside the group (or an individual session between counselor and client) may undermine the group process, it is a method selected by some. Position yourself in a way that doesn’t interrupt the counseling process. Sitting outside the group undermines the human connection between you, the counselor, and the client(s) and makes it more awkward for you to make a comment, if you have not been part of the process until then. For individual or family sessions, it is also recommended that the supervisor sit beside the counselor to fully observe what is occurring in the counseling session.

- The client should be informed about the process of supervision and the supervisor’s role and goals, essentially that the supervisor is there to observe the counselor’s skills and not necessarily the client.

- As preparation, the supervisor and supervisee should briefly discuss the background of the session, the salient issues the supervisee wishes to focus on, and the plans for the session. The role of the supervisor should be clearly stated and agreed on before the session.