8 Individual and Group Counseling Skills

Individual Counseling Skills

Components of the Therapeutic Alliance

Before we can move onto looking at some of the individual counseling skills themselves, it is important to identify components of a positive therapeutic alliance. There are literally dozens, if not hundreds, of characteristics that could be listed as elements of the positive therapeutic alliance, depending on who was asked. For the purposes of this book, we have identified what we feel are the most important.

Empathy

In order to develop a strong therapeutic connection, empathy is imperative. Empathy is the ability to listen to another’s story, understand context, and take their perspective. This includes the ability to accurately identify the individual’s thoughts and feelings and feel with them. It also involves being able to effectively communicate this with the other party.

Trust

Trust is a key component in the therapeutic relationship. It involves the ability of our clients to feel safe in sharing their experiences along with having confidence that we will not hurt or violate them. It’s important to note that trust is developed and earned over time and is a two-way street. Just as our clients need to trust us, we need to trust that they have the ability to make effective changes in their lives.

Active Listening

Active listening is vital to the therapeutic relationship. Active listening means being with our clients in the moment and not only hearing what they are saying, but being able to hypothesize as to the message they are trying to convey. It means being able to pay attention to nonverbal cues and read between the lines. Active listening also includes listening with the goal of understanding.

Cultural Competence

Human beings are multifaceted individuals. As a result, they have different worldviews and needs, given the intersection of these facets and their experiences in the world. Being culturally competent is an important characteristic for counselors to possess. It assists counselors in choosing approaches and interventions that are aligned with and respectful of a client’s culture. Demonstrating cultural competence helps clients to feel safe and acknowledges the importance of culture in the recovery process.

Flexibility and Adaptability

Treatment does not consist of a “one size fits all” approach. Thus, flexibility is a key component of the therapeutic relationship. Flexibility has many benefits, from being able to work with clients who have different backgrounds, experiences, personalities, problems, and needs, and tailoring interventions to best suit the individual, to knowing when it is appropriate to refer a client to another professional who can better help and meet their needs.

Adaptability is equally important. There is a saying that “nothing is constant but change.” This includes the counseling profession as well. Adaptability means being able to embrace that change is inevitable. It includes being able to grow from change, getting out of our comfort zone, having backup plans when the original doesn’t turn out the way we expected, and the willingness to grow as a professional through our commitment to being lifelong learners, including learning new skills.

Respect

The great humanistic psychologist Carl Rogers coined the term “unconditional positive regard”. It is the technique of accepting and supporting clients as who and how they are without conditions. Unconditional positive regard is in many ways tied to respect. It is important that counselors demonstrate respect for their clients as they are. This includes respecting a client’s thoughts, feelings, and decisions as their own, even when the counselor may not agree.

Boundaries

The importance of establishing and maintaining boundaries within the therapeutic relationship cannot be stressed enough. Boundaries are the parameters counselors establish that help ensure the therapeutic relationship remains effective and ethical.

treatment improvement protocol 35: enhancing motivation for change in substance use disorder treatment (adaptation)

motivational interviewing as a counseling style

Introduction to MI

MI is a counseling style based on the following assumptions:

- Ambivalence about substance use and change is normal and is an important motivational barrier to substance use behavior change.

- Ambivalence can be resolved by exploring the client’s intrinsic motivations and values.

- Your alliance with the client is a collaborative partnership to which you each bring important expertise.

- An empathic, supportive counseling style provides conditions under which change can occur.

You can use MI to effectively reduce or eliminate client substance use and other health-risk behaviors in many settings and across genders, ages, races, and ethnicities (DiClemente, Corno, Graydon, Wiprovnick, & Knoblach, 2017; Dillard, Zuniga, & Holstad, 2017; Lundahl et al., 2013). Analysis of more than 200 randomized clinical trials found significant efficacy of MI in the treatment of SUDs (Miller & Rollnick, 2014).

The MI counseling style helps clients resolve ambivalence that keeps them from reaching personal goals. MI builds on Carl Rogers’s (1965) humanistic theories about people’s capacity for exercising free choice and self-determination. Rogers identified the sufficient conditions for client change, which are now called “common factors” of therapy, including counselor empathy (Miller & Moyers, 2017).

As a counselor, your main goals in MI are to express empathy and elicit clients’ reasons for and commitment to changing substance use behaviors (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). MI is particularly helpful when clients are in the Precontemplation and Contemplation stages of the Stages of Change (SOC), when readiness to change is low, but it can also be useful throughout the change cycle.

The Spirit of MI

Use an MI counseling style to support partnership with clients. Collaborative counselor–client relationships are the essence of MI, without which MI counseling techniques are ineffective. Counselor MI spirit is associated with positive client engagement behaviors (e.g., self-disclosure, cooperation) (Romano & Peters, 2016) and positive client outcomes in health-related behaviors (e.g., exercise, medication adherence) similar to those in addiction treatment (Copeland, McNamara, Kelson, & Simpson, 2015).

The spirit of MI (Miller & Rollnick, 2013) comprises the following elements:

- Partnership refers to an active collaboration between you and the client. A client is more willing to express concerns when you are empathetic and show genuine curiosity about the client’s perspective. In this partnership, you are influential, but the client drives the conversation.

- Acceptance refers to your respect for and approval of the client. This doesn’t mean agreeing with everything the client says but is a demonstration of your intention to understand the client’s point of view and concerns. In the context of MI, there are four components of acceptance:

- Absolute worth: Prizing the inherent worth and potential of the client

- Accurate empathy: An active interest in, and an effort to understand, the client’s internal perspective reflected by your genuine curiosity and reflective listening

- Autonomy support: Honoring and respecting a client’s right to and capacity for self-direction

- Affirmation: Acknowledging the client’s values and strengths

- Compassion refers to your active promotion of the client’s welfare and prioritization of client needs.

- Evocation elicits and explores motivations, values, strengths, and resources the client already has.

To remember the four elements, use the acronym PACE (Stinson & Clark, 2017). The specific counseling strategies you use in your counseling approach should emphasize one or more of these elements.

Principles of Person-Centered Counseling

MI reflects a longstanding tradition of humanistic counseling and the person-centered approach of Carl Rogers. It is theoretically linked to his theory of the “critical conditions for change,” which states that clients change when they are engaged in a therapeutic relationship in which the counselor is genuine and warm, expresses unconditional positive regard, and displays accurate empathy (Rogers, 1965).

MI adds another dimension in your efforts to provide person-centered counseling. In MI, the counselor follows the principles of person-centered counseling, but also guides the conversation toward a specific, client-driven change goal. MI is more directive than purely person-centered counseling; it is guided by the following broad person-centered counseling principles (Miller & Rollnick, 2013):

- SUD treatment services exist to help recipients. The needs of the client take precedence over the counselor’s or organization’s needs or goals.

- The client engages in a process of self-change. You facilitate the client’s natural process of change.

- The client is the expert on his or her own life and has knowledge of what works and what doesn’t.

- As the counselor, you do not make change happen.

- People have their own motivation, strengths, and resources. Counselors help activate those resources.

- You are not responsible for coming up with all the good ideas about change, and you probably don’t have the best ideas for any particular client.

- Change requires a partnership and “collaboration of expertise.”

- You must understand the client’s perspectives on his or her problems and need to change.

- The counseling relationship is not a power struggle. Conversations about change should not become debates. Avoid arguing with or trying to persuade the client that your position is correct.

- Motivation for change is evoked from, not given to, the client.

- People make their own decisions about taking action. It is not a change goal until the client says so.

- The spirit of MI and client-centered counseling principles foster a sound therapeutic alliance.

Research on person-centered counseling approaches consistent with MI in treating alcohol use disorder (AUD) found that several sessions improved client outcomes, including readiness to change and reductions in alcohol use (Barrio & Gual, 2016).

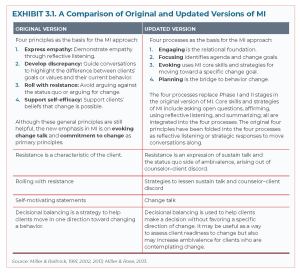

What Is New in MI

Much has changed in MI since Miller and Rollnick’s original (1991) and updated (2002) work. Exhibit 3.1 summarizes important changes to MI based on decades of research and clinical experience.

Exhibit 3.2 presents common misconceptions about MI and provides clarification of MI’s underlying theoretical assumptions and counseling approach, which are described in the rest of this chapter.

Ambivalence

A key concept in MI is ambivalence. It is normal for people to feels two ways about making an important change in their lives. Frequently, client ambivalence is a roadblock to change, not a lack of knowledge or skills about how to change (Forman & Moyers, 2019). Individuals with SUDs are often aware of the risks associated with their substance use, but continue to use substances anyway. They may need to stop using substances, but they continue to use. The tension between these feelings is ambivalence.

Ambivalence about changing substance use behaviors is natural. As clients move from Precontemplation to Contemplation, their feelings of conflict about change increase. This tension may help move people toward change, but often the tension of ambivalence leads people to avoid thinking about the problem. They may tell themselves things aren’t so bad (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). View ambivalence not as denial or resistance, but as a normal experience in the change process. If you interpret ambivalence as denial or resistance, you are likely to evoke discord between you and clients, which is counterproductive.

Sustain Talk and Change Talk

Recognizing sustain talk and change talk in clients will help you better explore and address their ambivalence.

Sustain talk consists of client statements that support not changing a health-risk behavior, like substance misuse. Change talk consists of client statements that favor change (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). Sustain talk and change talk are expressions of both sides of ambivalence about change. Over time, MI has evolved in its understanding of what keeps clients stuck in ambivalence about change and what supports clients to move in the direction of changing substance use behaviors. Client stuck in ambivalence will engage in a lot of sustain talk, whereas clients who are more ready to change will engage in more change talk with stronger statements supporting change.

Greater frequency of client sustain talk in sessions is linked to poorer substance use treatment outcomes (Lindqvist, Forsberg, Enebrink, Andersson, & Rosendahl, 2017; Magill et al., 2014; Rodriguez, Walters, Houck, Ortiz, & Taxman, 2017). Conversely, MI-consistent counselor behavior focused on eliciting and reflecting change talk, more client change talk compared with sustain talk, and stronger commitment change talk are linked to better substance use outcomes (Barnett, Moyers, et al., 2014; Borsari et al., 2018; Houck, Manuel, & Moyers, 2018; Magill et al., 2014, 2018; Romano & Peters, 2016). Counselor empathy is also linked to eliciting client change talk (Pace et al., 2017).

Another development in MI is the delineation of different kinds of change talk. The acronym for change talk in MI is DARN-CAT (Miller & Rollnick, 2013):

- Desire to change: This is expressed in statements about wanting something different— “I want to find an Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) meeting” or “I hope to start going to AA.”

- Ability to change: This is expressed in statements about self-perception of capability— “I could start going to AA.”

- Reasons to change: This is expressed as arguments for change—“I’d probably learn more about recovery if I went to AA” or “Going to AA would help me feel more supported.”

- Need to change: This is expressed in client statements about importance or urgency—“I have to stop drinking” or “I need to find a way to get my drinking under control.”

- Commitment: This is expressed as a promise to change—“I swear I will go to an AA meeting this year” or “I guarantee that I will start AA by next month.”

- Activation: This is expressed in statements showing movement toward action—“I’m ready to go to my first AA meeting.”

- Taking steps: This is expressed in statements indicating that the client has already done something to change—“I went to an AA meeting” or “I avoided a party where friends would be doing drugs.”

Exhibit 3.3 depicts examples of change talk and sustain talk that correspond to DARN-CAT.

To make the best use of clients’ change talk and sustain talk that arise in sessions, remember to:

- Recognize client expressions of change talk but don’t worry about differentiating various kinds of change talk during a counseling session.

- Use reflective listening to reinforce and help clients elaborate on change talk.

- Use DARN-CAT in conversations with clients.

- Recognize sustain talk and use MI strategies to lessen the impact of sustain talk on clients’ readiness to change (see discussion on responding to change talk and sustain talk in the next section).

- Be aware that both sides of ambivalence (change talk and sustain talk) will be present in your conversations with clients.

A New Look at Resistance

Understanding the role of resistance and how to respond to it can help you maintain good counselor–client rapport.

Resistance in SUD treatment has historically been considered a problem centered in the client. As MI has developed over the years, its understanding of resistance has changed. Instead of emphasizing resistance as a pathological defense mechanism, MI views resistance as a normal part of ambivalence and a client’s reaction to the counselor’s approach in the moment (Miller & Rollnick, 2013).

A client may express resistance in sustain talk that favors the “no change” side of ambivalence. The way you respond to sustain talk can contribute to the client becoming firmly planted in the status quo or help the client move toward contemplating change. For example, the client’s show of ambivalence about change and your arguments for change can create discord in your therapeutic relationship.

Client sustain talk is often evoked by discord in the counseling relationship (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). Resistance is a two-way street. If discord arises in conversation, change direction or listen more carefully. This is an opportunity to respond in a new, perhaps surprising, way and to take advantage of the situation without being confrontational. This new way of looking at resistance is consistent with the principles of person-centered counseling described at the beginning of the chapter.

Here is an example of what MI is NOT:

Core Skills of MI: OARS

To remember the core counseling skills of MI, use the acronym OARS (Miller & Rollnick, 2013):

- Asking Open questions

- Affirming

- Reflective listening

- Summarizing

These core skills are consistent with the principles of person-centered counseling and can be used throughout your work with clients. If you use these skills, you will more likely have greater success in engaging clients and less incidence of discord within the counselor–client relationship. These core skills are described below.

Asking Open Questions

Use open questions to invite clients to tell their story rather than closed questions, which merely elicit brief information. Open questions are questions that invite clients to reflect before answering and encourage them to elaborate. Asking open questions helps you understand their point of view. Open questions facilitate a dialog and do not require any particular response from you. They encourage clients to do most of the talking and keep the conversation moving forward. Closed questions evoke yes/no or short answers and sometimes make clients feel as if they have to come up with the right answer. One type of open question is actually a statement that begins with “Tell me about” or “Tell me more about.” The “Tell me about” statement invites clients to tell a story and serves as an open question.

Examples

Examples of closed questions:

- “So you are here because you are concerned about your use of alcohol, correct?”

- “How many children do you have?”

- “Do you agree that it would be a good idea for you to go through detoxification?”

- “On a typical day, how much marijuana do you smoke?

- “Did your doctor tell you to quit smoking?”

Examples of open questions:

- “What is it that brings you here today?”

- “Tell me about your family.”

- “What do you think about the possibility of going through detoxification?”

- “Tell me about your marijuana use on a typical day.”

- “In what ways are you concerned about your use of amphetamines?”

There may be times when you must ask closed questions, for example, to gather information for a screening or assessment. However, if you use open questions—“Tell me about the last time you used methamphetamines”—you will often get the information you need and enhance the process of engagement. During assessment, avoid the question-and-answer trap, which can decrease rapport, become an obstacle to counselor–client engagement, and stall conversations.

MI involves maintaining a balance between asking questions and reflective listening (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). Ask one open question and follow it with two or more reflective listening responses.

Affirming

Affirming is a way to express your genuine appreciation and positive regard for clients (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). Affirming clients supports and promotes self-efficacy. By affirming, you are saying, “I see you, what you say matters, and I want to understand what you think and feel” (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). Affirming can boost clients’ confidence about taking action. Using affirmations in conversations with clients consistently predicts positive client outcomes (Romano & Peters, 2016).

When affirming:

- Emphasize client strengths, past successes, and efforts to take steps, however small, to accomplish change goals.

- Do not confuse this type of feedback with praise, which can sometimes be a roadblock to effective listening.

- Frame your affirming statements with “you” instead of “I.” For example, instead of saying “I am proud of you,” which focuses more on you than on the client, try “You have worked really hard to get to where you are now in your life,” which demonstrates your appreciation, but keeps the focus on the client (Miller & Rollnick, 2013).

- Use statements such as (Miller & Rollnick, 2013):

- “You took a big step in coming here ”

- “You got discouraged last week, but kept going to your AA. You are persistent.”

- “Although things didn’t turn out the way you hoped, you tried really hard, and that means a lot.”

- “That’s a good idea for how you can avoid situations where you might be tempted to drink.”

There may be ethnic, cultural, and even personal differences in how people respond to affirming statements. Be aware of verbal and nonverbal cues about how the client is reacting and be open to checking out the client’s reaction with an open question—“How was that for you to hear?” Strategies for forming affirmations that account for cultural and personal differences include (Rosengren, 2018):

- Focusing on specific behaviors to affirm.

- Avoiding using “I.”

- Emphasizing descriptions instead of evaluations.

- Emphasizing positive developments instead of continuing problems.

- Affirming interesting qualities and strengths of clients.

- Holding an awareness of client strengths instead of deficits as you formulate affirmations.

Reflective Listening

Reflective listening is the key component of expressing empathy. Reflective listening is fundamental to person-centered counseling in general and MI in particular (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). Reflective listening (Miller & Rollnick, 2013):

- Communicates respect for and acceptance of clients.

- Establishes trust and invites clients to explore their own perceptions, values, and feelings.

- Encourages a nonjudgmental, collaborative relationship.

- Allows you to be supportive without agreeing with specific client statements.

Reflective listening builds collaboration and a safe and open environment that is conducive to examining issues and eliciting the client’s reasons for change. It is both an expression of empathy and a way to selectively reinforce change talk (Romano & Peters, 2016). Reflective listening demonstrates that you are genuinely interested in understanding the client’s unique perspective, feelings, and values. Expressions of counselor empathy predict better substance use outcomes (Moyers, Houck, Rice, Longabaugh, & Miller, 2016). Your attitude should be one of acceptance, but not necessarily approval or agreement, recognizing that ambivalence about change is normal.

Consider ethnic and cultural differences when expressing empathy through reflective listening. These differences influence how both you and the client interpret verbal and nonverbal communications.

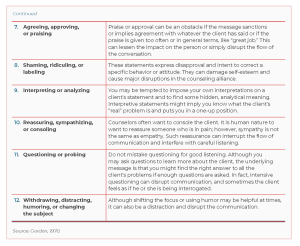

Reflective listening is not as easy as it sounds. It is not simply a matter of being quiet while the client is speaking. Reflective listening requires you to make a mental hypothesis about the underlying meaning or feeling of client statements, then reflect that back to the client with your best guess about his or her meaning or feeling (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). Gordon (1970) called this “active listening” and identified 12 kinds of responses that people often give to others that are not active listening and can actually derail a conversation. Exhibit 3.5 describes these roadblocks to listening.

If you engage in any of these 12 activities, you are talking and not listening. However well intentioned, these roadblocks to listening shift the focus of the conversation from the client to the counselor. They are not consistent with the principles of person-centered counseling.

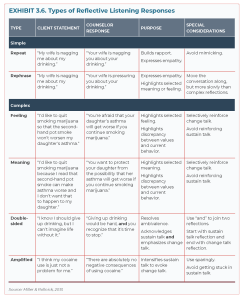

Types of reflective listening

In MI, there are several kinds of reflective listening responses that range from simple (e.g., repeating or rephrasing a client statement) to complex (e.g., using different words to reflect the underlying meaning or feeling of a client statement). Simple reflections engage clients and let them know that you’re genuinely interested in understanding their perspective. Complex reflections invite clients to deepen their self-exploration (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). In MI, there are special complex reflections that you can use in specific counseling situations, like using a double-sided reflection when clients are expressing ambivalence about changing a substance use behavior. Exhibit 3.6 provides examples of simple and complex reflective listening responses to client statements about substance use.

Forming complex reflections

Simple reflections are fairly straightforward. You simply repeat or paraphrase what the client said. Complex reflections are more challenging. A statement could have many meanings. The first step in making a complex reflection of meaning or feelings is to make a hypothesis in your mind about what the client is trying to say (Miller & Rollnick, 2013).

Use these steps to form a mental hypothesis about meaning or feelings:

- If the client says, “I drink because I am lonely,” think about the possible meanings of “lonely.” Perhaps the client is saying, “I lost my spouse” or “It is hard for me to make friends” or “I can’t think of anything to say when I am with my family.”

- Consider the larger conversational context. Has the client noted not having much of a social life?

- Make your best guess about the meaning of the client’s statement.

- Offer a reflective listening response—“You drink because it is hard for you to make friends.”

- Wait for the client’s response. The client will tell you either verbally or nonverbally if your guess is correct. If the client continues to talk and expands on the initial statement, you are on target.

- Be open to being wrong. If you are, use client feedback to make another hypothesis about the client’s meaning.

Remember that reflective listening is about refraining from making assumptions about the underlying message of client statements, making a hypothesis about the meaning or feeling of the statement, and then checking out your hypothesis by offering a reflective statement and listening carefully to the client’s response (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). Reflective listening is basic to all four MI processes. Follow open questions with at least one reflective listening response—but preferably two or three responses—before asking another question. A higher ratio of reflections to questions consistently predicts positive client outcomes (Romano & Peters, 2016). It takes practice to become skillful, but the effort is worth it because careful reflective listening builds a therapeutic alliance and facilitates the client’s self-exploration—two essential components of person-centered counseling (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). The key to expressing accurate empathy through reflective listening is your ability to shift gears from being an expert who gives advice to being an individual supporting the client’s autonomy and expertise in making decisions about changing substance use behaviors (Moyers, 2014).

Summarizing

Summarizing is a form of reflective listening that distills the essence of several client statements and reflects them back to him or her. It is not simply a collection of statements. You intentionally select statements that may have particular meaning for the client and present them in a summary that paints a fuller picture of the client’s experience than simply using reflections (Miller & Rollnick, 2013).

There are several types of summarization in MI (Miller & Rollnick, 2013):

- Collecting summary: Recalls a series of related client statements, creating a narrative to reflect on.

- Linking summary: Reflects a client statement; links it to an earlier statement.

- Transitional summary: Wraps up a conversation or task; moves the client along the change process.

- Ambivalence summary: Gathers client statements of sustain talk and change talk during a session. This summary should acknowledge sustain talk, but reinforce and highlight change talk.

- Recapitulation summary: Gathers all of the change talk of many conversations. It is useful during the transition from one stage to the next when making a change plan.

At the end of a summary, ask the client whether you left anything out. This opportunity lets the client correct or add more to the summary and often leads to further discussion. Summarizing encourages client self-reflection.

Summaries reinforce key statements of movement toward change. Clients hear change talk once when they make a statement, twice when the counselor reflects it, and again when the counselor summarizes the discussion.

Let’s take a look at an effective example of MI in action:

Four Processes of MI

MI has moved away from the idea of phases of change to overlapping processes that more accurately describe how MI works in clinical practice. This change is a shift away from a linear, rigid model of change to a circular, fluid model of change within the context of the counseling relationship. This section reviews these MI processes, summarizes counseling strategies appropriate for each process, and integrates the four principles of MI from previous versions.

Engaging

Engaging clients is the first step in all counseling approaches. Specific counseling strategies or techniques will not be effective if you and the client haven’t established a strong working relationship. MI is no exception to this. Miller and Rollnick (2013) define engaging in MI “as the process of establishing a mutually trusting and respectful helping relationship” (p. 40). Research supports the link between your ability to develop this kind of helping relationship and positive treatment outcomes such as reduced drinking (Moyers et al., 2016; Romano & Peters, 2016).

Opening strategies

Opening strategies promote engagement in MI by emphasizing OARS in the following ways:

- Ask open questions instead of closed questions.

- Offer affirmations of client self-efficacy, hope, and confidence in the client’s ability to change.

- Emphasize reflective listening.

- Summarize to reinforce that you are listening and genuinely interested in the client’s perspective.

- Determine the client’s readiness to change or specific stage in the stages of change.

- Avoid prematurely focusing on taking action.

- Try not to identify the client’s treatment goals until you have sufficiently explored the client’s readiness. Then you can address the client’s ambivalence.

These opening strategies ensure support for the client and help the client explore ambivalence in a safe setting. In the following initial conversation, the counselor uses OARS to establish rapport and address the client’s drinking through reflective listening and asking open questions:

Counselor: Jerry, thanks for coming in. (Affirmation) What brings you here today? (Open question)

Client: My wife thinks I drink too much. She says that’s why we argue all the time. She also thinks that my drinking is ruining my health.

Counselor: So your wife has some concerns about your drinking interfering with your relationship and harming your health. (Reflection)

Client: Yeah, she worries a lot.

Counselor: You wife worries a lot about the drinking. (Reflection) What concerns you about it? (Open question)

Client: I’m not sure I’m concerned about it, but I do wonder sometimes if I’m drinking too much.

Counselor: You are wondering about the drinking. (Reflection) Too much for…? (Open question that invites the client to complete the sentence)

Client: For my own good, I guess. I mean it’s not like it’s really serious, but sometimes when I wake up in the morning, I feel really awful, and I can’t think straight most of the morning.

Counselor: It messes up your thinking, your concentration. (Reflection)

Client: Yeah, and sometimes I have trouble remembering things.

Counselor: And you wonder if these problems are related to drinking too much. (Reflection)

Client: Well, I know it is sometimes.

Counselor: You’re certain that sometimes drinking too much hurts you. (Reflection) Tell me what it’s like to lose concentration and have trouble remembering. (Open question in the form of a statement)

Client: It’s kind of scary. I am way too young to have trouble with my memory. And now that I think about it, that’s what usually causes the arguments with my wife. She’ll ask me to pick up something from the store and when I forget to stop on my way home from work, she starts yelling at me.

Counselor: You’re scared that drinking is starting to have some negative effects on what’s important to you, like your ability to think clearly and good communication with your wife. (Reflection)

Client: Yeah. But I don’t think I’m an alcoholic or anything.

Counselor: You don’t think you’re that bad off, but you do wonder if maybe you’re overdoing it and hurting yourself and your relationship with your wife. (Reflection)

Client: Yeah.

Counselor: You know, Jerry, it takes courage to come talk to a stranger about something that’s scary to talk about. (Affirmation) What do you think? (Open question)

Client: I never thought of it like that. I guess it is important to figure out what to do about my drinking.

Counselor: So, Jerry, let’s take a minute to review where we are today. Your wife is concerned about how much you drink. You have been having trouble concentrating and remembering things and are wondering if that has to do with how much you are drinking. You are now thinking that you need to figure out what to do about the drinking. Did I miss anything? (Summary)

Avoiding traps

Identify and avoid traps to help preserve client engagement. The above conversation shows use of core MI skills to engage the client and help him feel heard, understood, and respected while moving the conversation toward change. The counselor avoids common traps that increase disengagement.

Common traps to avoid include the following (Miller & Rollnick, 2013):

-

- The Expert Trap: People often see a professional, like a primary care physician or nurse practitioner, to get answers to questions and to help them make important decisions. But relying on another person (even a professional) to have all the answers is contrary to the spirit of MI and the principles of person-centered care. Both you and the client have expertise. You have knowledge and skills in listening and interviewing; the client has knowledge based on his or her life experience. In your conversations with a client, remember that you do not have to have all the answers, and trust that the client has knowledge about what is important to him or her, what needs to change, and what steps need to be taken to make those changes. Avoid falling into the expert trap by:

- Refraining from acting on the “righting reflex,” the natural impulse to jump into action and direct the client toward a specific change. Such a directive style is likely to produce sustain talk and discord in the counseling relationship.

- Not arguing with the client. If you try to prove a point, the client predictably takes the opposite side. Arguments with the client can rapidly degenerate into a power struggle and do not enhance motivation for change.

- The Expert Trap: People often see a professional, like a primary care physician or nurse practitioner, to get answers to questions and to help them make important decisions. But relying on another person (even a professional) to have all the answers is contrary to the spirit of MI and the principles of person-centered care. Both you and the client have expertise. You have knowledge and skills in listening and interviewing; the client has knowledge based on his or her life experience. In your conversations with a client, remember that you do not have to have all the answers, and trust that the client has knowledge about what is important to him or her, what needs to change, and what steps need to be taken to make those changes. Avoid falling into the expert trap by:

-

- The Labeling Trap: Diagnoses and labels like “alcoholic” or “addict” can evoke shame in clients. There is no evidence that forcing a client to accept a label is helpful; in fact, it usually evokes discord in the counseling relationship. In the conversation above, the counselor didn’t argue with Jerry about whether he is an “alcoholic.” If the counselor had done so, the outcome would likely have been different:

Client: But I don’t think I’m an alcoholic or anything.

Counselor: Well, based on what you’ve told me, I think we should do a comprehensive assessment to determine whether or not you are.

Client: Wait a minute. That’s not what I came for. I don’t think counseling is going to help me.

-

- The Question-and-Answer Trap: When your focus is on getting information from a client, particularly during an assessment, you and the client can easily fall into the question-and-answer trap. This can feel like an interrogation rather than a conversation. In addition, a pattern of asking closed questions and giving short answers sets you up in the expert role, and the client becomes a passive recipient of the treatment intervention instead of an active partner in the process. Remember to ask open questions, and follow them with reflective listening responses to avoid the question-and-answer trap.

- The Premature Focus Trap: You can fall into this trap when you focus on an agenda for change before the client is ready—for example, jumping into solving problems before developing a strong working alliance. When you focus on an issue that is important to you (e.g., admission to an inpatient treatment program), but not to the client, discord will occur. Remember that your approach should match where the client is with regard to his or her readiness to change.

- The Blaming Trap: Clients often enter treatment focused on who is to blame for their substance use problem. They may feel guarded and defensive, expecting you to judge them harshly as family, friends, coworkers, or others may have. Avoid the blame trap by immediately reassuring clients that you are uninterested in blaming anyone and that your role is to listen to what troubles them.

Focusing

Once you have engaged the client, the next step in MI is to find a direction for the conversation and the counseling process as a whole. This is called focusing in MI. With the client, you develop a mutually agreed-on agenda that promotes change and then identify a specific target behavior to discuss. Without a clear focus, conversations about change can be unwieldy and unproductive (Miller & Rollnick, 2013).

Deciding on an agenda

MI is essentially a conversation you and the client have about change. The direction of the conversation is influenced by the client, the counselor, and the clinical setting (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). For example, a client walking through the door of an outpatient SUD treatment program understands that his or her use of alcohol and other drugs will be on the agenda.

Clients, however, may be mandated to treatment and may not see their substance use as a problem, or they may have multiple issues (e.g., child care, relational, financial, legal problems) that interfere with recovery and that need to be addressed. When clients bring multiple problems to the table or are confused or uncertain about the direction of the conversation, you can engage in agenda mapping, which is a process consistent with MI that helps you and clients decide on the counseling focus. Exhibit 3.7 displays the components in an agenda map.

Identifying a target behavior

Once you and the client agree on a general direction, focus on a specific behavior the client is ready to discuss. Change talk links to a specific behavior change target (Miller & Rollnick, 2010); you can’t evoke change talk until you identify a target behavior. For example, if the client is ready to discuss drinking, guide the conversation toward details specific to that concern. A sample of such a conversation follows:

Counselor: Marla, you said you’d like to talk about your drinking. It would help if you’d give me a sense of what your specific concerns are about drinking. (Open question in the form of a statement)

Client: Well, after work I go home to my apartment and I am so tired; I don’t want to do anything but watch TV, microwave a meal, and drink till I fall asleep. Then I wake up with a big hangover in the morning and have a hard time getting to work on time. My supervisor has given me a warning.

Counselor: You’re worried that the amount you drink affects your sleep and ability to get to work on time. (Reflection) What do you think you’d like to change about the drinking? (Open question)

Client: I think I need to stop drinking completely for a while, so I can get into a healthy sleep pattern.

Counselor: So I’d like to put stop drinking for a while on the map, is that okay? [Asks permission. Pauses. Waits for permission.] Let’s focus our conversations on that goal.

Notice that this client is already expressing change talk about her alcohol use. By narrowing the focus from drinking as a general concern to stopping drinking as a possible target behavior, the counselor moved into the MI process of evoking.

Evoking

Evoking elicits client motivations for change. It shapes conversations in ways that encourage clients, not counselors, to argue for change. Evoking is the core of MI and differentiates it from other counseling methods (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). The following sections explore evoking change talk, responding to change talk and sustain talk, developing discrepancy, evoking hope and confidence to support self-efficacy, recognizing signs of readiness to change, and asking key questions.

Evoking change talk

Engaging the client in the process of change is the fundamental task of MI. Rather than identifying the problem and promoting ways to solve it, your task is to help clients recognize that their use of substances may be contributing to their distress and that they have a choice about how to move forward in life in ways that enhance their health and well-being. One signal that clients’ ambivalence about change is decreasing is when they start to express change talk.

The first step to evoking change talk is to ask open questions. There are seven kinds of change talk, reflected in the DARN acronym. DARN questions can help you generate open questions that evoke change talk. Exhibit 3.8 provides examples of open questions that elicit change talk in preparation for taking steps to change.

Examples of Open Questions to Evoke Change Talk

DESIRE

- “How would you like for things to change?”

- “What do you hope our work together will accomplish?” “What don’t you like about how things are now?”

- “What don’t you like about the effects of drinking or drug use?” “What do you wish for your relationship with ________?”

- “How do you want your life to be different a year from now?” “What are you looking for from this program?”

ABILITY

- “If you decided to quit drinking, how could you do it?” “What do you think you might be able to change?” “What ideas do you have for how you could ?”

- “What encourages you that you could change if you decided to?”

- “How confident are you that you could if you made up your mind?”

- “Of the different options you’ve considered, what seems most possible?”

- “How likely are you to be able to ?”

REASONS

- “What are some of the reasons you have for making this change?”

- “Why would you want to stop or cut back on your use of _______?”

- “What’s the downside of the way things are now?”

- “What might be the good things about quitting _________?”

- “What would make it worthwhile for you to __________?”

- “What might be some of the advantages of __________?”

- “What might be the three best reasons for ________ ?”

NEED

- “What needs to happen?”

- “How important is it for you to ________?”

- “What makes you think that you might need to make a change?”

- “How serious or urgent does this feel to you?”

- “What do you think has to change?”

Source: Miller & Rollnick, 2013. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change (3rd ed.), pp. 171‒173. Adapted with permission from Guilford Press.

Other strategies for evoking change talk (Miller & Rollnick, 2013) include:

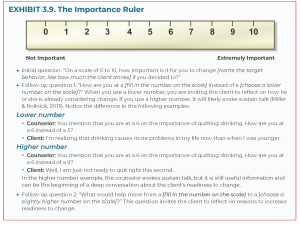

- Eliciting importance of change. Ask an open question that elicits “Need” change talk (Exhibit 3.8): “How important is it for you to [name the change in the target behavior, such as cutting back on drinking]?” You can also use scaling questions such as those in the Importance Ruler in Exhibit 3.9 to help the client explore change talk about need more fully.

- Exploring extremes. Ask the client to identify the extremes of the problem; this enhances his or her motivation. For example: “What concerns you the most about [name the target behavior, like using cocaine]?”

- Looking back. To point out discrepancies and evoke change talk, ask the client about what it was like before experiencing substance use problems, and compare that response with what it is like now. For example: “What was it like before you started using heroin?”

- Looking forward. Ask the client to envision what he or she would like for the future. This can elicit change talk and identify goals to work toward. For example: “If you decided to [describe the change in target behavior, such as quit smoking], how do you think your life would be different a month, a year, or 5 years from now?”

Reinforce change talk by reflecting it back verbally, nodding, or making approving facial expressions and affirming statements. Encourage the client to continue exploring the possibility of change by asking for elaboration, explicit examples, or details about remaining concerns. Questions that begin with “What else” effectively invite elaboration.

Your task is to evoke change talk and selectively reinforce it via reflective listening. The amount of change talk versus sustain talk is linked to client behavior change and positive substance use outcomes (Houck et al., 2018; Lindqvist et al., 2017; Magill et al., 2014).

Responding to change talk and sustain talk

Your focus should be on evoking change talk and minimizing sustain talk. Sustain talk expresses the side of ambivalence that favors continuing one’s pattern of substance use. Don’t argue with the client’s sustain talk, and don’t try to persuade the client to take the change side of ambivalence.

There are many ways to respond to sustain talk that acknowledge it without getting stuck in it. You can use (Miller & Rollnick, 2013):

- Simple reflections. Acknowledge sustain talk with a simple reflective listening response. This validates what the client has said and sometimes elicits change talk. Give the client an opportunity to respond before moving on.

Client: I don’t plan to quit drinking anytime soon.

Counselor: You don’t think that abstinence would work for you right now.

- Amplified reflections. Accurately reflect the client’s statement, but with emphasis (and without sarcasm). An amplified reflection overstates the client’s point of view, which can nudge the client to take the other side of ambivalence (i.e., change talk).

Client: But I can’t quit smoking pot. All my friends smoke pot.

Counselor: So you really can’t quit because you’d be too different from your friends.

- Double-sided reflections. A double-sided reflection acknowledges sustain talk, then pairs it with change talk either in the same client statement or in a previous statement. It acknowledges the client’s ambivalence yet selectively reinforces change talk. Use “and” to join the two statements and make change talk the second statement (see Counselor Response in Exhibit 3.6).

Client: I know I should quit smoking now that I am pregnant. But I tried to go cold turkey before, and it was just too hard.

Counselor: You’re worried that you won’t be able to quit all at once, and you want your baby to be born healthy.

- Agreements with a twist. A subtle strategy is to agree, but with a slight twist or change of direction that moves the discussion forward. The twist should be said without emphasis or sarcasm.

Client: I can’t imagine what I would do if I stopped drinking. It’s part of who I am. How could I go to the bar and hang out with my friends?

Counselor: You just wouldn’t be you without drinking. You have to keep drinking no matter how it affects your health.

- Reframing. Reframing acknowledges the client’s experience yet suggests alternative meanings. It invites the client to consider a different perspective (Barnett, Spruijt-Metz, et al., 2014). Reframing is also a way to refocus the conversation from emphasizing sustain talk to eliciting change talk (Barnett, Spruijt-Metz, et al., 2014).

Client: My husband always nags me about my drinking and calls me an alcoholic. It bugs me.

Counselor: Although your husband expresses it in a way that frustrates you, he really cares and is concerned about the drinking.

- A shift in focus. Defuse discord and tension by shifting the conversational focus.

Client: The way you’re talking, you think I’m an alcoholic, don’t you?

Counselor: Labels aren’t important to me. What I care about is how to best help you.

- Emphasis on personal autonomy. Emphasizing that people have choices (even if all the choices have a downside) reinforces personal autonomy and opens up the possibility for clients to choose change instead of the status quo. When you make these statements, remember to use a neutral, nonjudgmental tone, without sarcasm. A dismissive tone can evoke strong reactions from the client.

Client: I am really not interested in giving up drinking completely.

Counselor: It’s really up to you. No one can make that decision for you.

All of these strategies have one thing in common: They are delivered in the spirit of MI.

Developing discrepancy: A values conversation

Developing discrepancy has been a key element of MI since its inception. It was originally one of the four principles of MI. In the current version, exploring the discrepancy between clients’ values and their substance use behavior has been folded into the evoking process. When clients recognize discrepancies in their values, goals, and hopes for the future, their motivation to change increases.

Your task is to help clients focus on how their behavior conflicts with their values and goals. The focus is on intrinsic motivation. MI doesn’t work if you focus only on how clients’ substance use behavior is in conflict with external pressure (e.g., family, an employer, the court) (Miller & Rollnick, 2013).

To facilitate discrepancy, have a values conversation to explore what is important to the client (e.g., good heath, positive relationships with family, being a responsible member of the community, preventing another hospitalization, staying out of jail), then highlight the conflict the client feels between his or her substance use behaviors and those values. Client experience of discrepancy between values and substance use behavior is related to better client outcomes (Apodaca & Longabaugh, 2009).

This process can raise uncomfortable feelings like guilt or shame. Frame the conversation by conveying acceptance, compassion, and affirmation. The paradox of acceptance is that it helps people tolerate more discrepancy and, instead of avoiding that tension, propels them toward change (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). However, too much discrepancy may overwhelm the client and cause him or her to think change is not possible (Miller & Rollnick, 2013).

To help a client perceive discrepancy, you can use what is sometimes termed the “Columbo approach.” Initially developed by Kanfer & Schefft (1988), this approach remains a staple of MI and is particularly useful with a client who is in the Precontemplation stage and needs to be in charge of the conversation. Essentially, the counselor expresses understanding and continuously seeks clarification of the client’s problem, but appears unable to perceive any solution.

In addition to providing personalized feedback, you can facilitate discrepancy by (Miller & Rollnick, 2013):

- Identifying personal values. For clients to feel discrepancy between their values and actions, they need to recognize what those values are. Some clients may have only a vague understanding of their values or goals. A tool to help you and clients explore values is the Values Card Sort.

-

- Print different values like “Achievement—to have important accomplishments” (Miller & Rollnick, 2013, p. 80) on individual cards.

- Invite clients to sort the cards into piles by importance; those that are most important are placed in one pile, and those that are least important are in another pile.

- Ask clients to pick up to 10 cards from the most important pile; converse about each one.

- Use OARS to facilitate the conversations.

- Pay attention to statements about discrepancy between these important values and clients’ substance use behaviors, and reinforce these statements.

- A downloadable, public domain version of the Value Card Sort activity is available online (www.motivationalinterviewing.org/sites/ default/fles/valuescardsort_0.pdf).

-

- Providing information. Avoid being the expert and treating clients as passive recipients when giving information about the negative physical, emotional, mental, social, or spiritual effects or consequences of substance misuse. Instead, engage the client in a process of mutual exchange. This process is called Elicit-Provide-Elicit (EPE) and has three steps (Miller & Rollnick, 2013):

- Elicit readiness or interest in the information. Don’t assume that clients are interested in hearing the information you want to offer; start by asking permission. For example: “Would it be okay if I shared some information with you about the health risks of using heroin?” Don’t assume that clients lack this knowledge. Ask what they already know about the risks of using heroin. For example: “What would you most like to know about the health risks of heroin use?”

- Provide information neutrally (i.e., without judgement). Prioritize what clients have said they would most like to know. Fill in knowledge gaps. Present the information clearly and in small chunks. Too much information can overwhelm clients. Invite them to ask more questions about the information you’re providing.

- Elicit clients’ understanding of the information. Don’t assume that you know how clients will react to the information you have provided. Ask questions:

“So, what do you make of this information?”

“What do you think about that?”

“How does this information impact the way you might be thinking about [name the substance use behavior, such as drinking]?”

Allow clients plenty of time to consider and reflect on the information you presented. Invite them to ask questions for clarification. Follow clients’ responses to your open questions with reflective listening statements that emphasize change talk whenever you hear it. EPE is an MI strategy to facilitate identifying discrepancy and is an effective and respectful way to give advice to clients about behavior change strategies during the planning process.

- Exploring others’ concerns. Another way to build discrepancy is to explore the clients’ understanding of the concerns other people have expressed about their substance use. This differs from focusing on the external pressure that a family member, an employer, or the criminal justice system may be putting on clients to reduce or abstain from substance use. The purpose is to invite clients to explore the impact of substance use behaviors on the people with whom they are emotionally connected in a nonthreatening way. Approach this conversation from a place of genuine curiosity and even a bit of confusion (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). Here is a brief example of what this conversation might look like using an open question about a significant other’s concern, where reflecting sustain talk actually has the effect of eliciting change talk:

Counselor: You mentioned that your husband is concerned about your drinking. What do you think concerns him? (Open question)

Client: He worries about everything. The other day, he got really upset because I drove a block home from a friend’s house after a party. He shouldn’t worry so much. (Sustain talk)

Counselor: He’s worried that you could crash and hurt yourself or someone else or get arrested for driving under the influence. But you think his concern is overblown. (Complex reflection)

Client: I can see he may have a point. I really shouldn’t drive after drinking. (Change talk)

Evoking hope and confidence to support self-efficacy

Many clients do not have a well-developed sense of self-efficacy. They find it hard to believe that they can begin or maintain behavior change. Improving self-efficacy requires eliciting confidence, hope, and optimism that change, in general, is possible and that clients, specifically, can change. This positive impact on self-efficacy may be one of the ways MI promotes behavior change (Chariyeva et al., 2013).

One of the most consistent predictors of positive client behavior change is “ability” change talk (Romano & Peters, 2016). Unless a client believes change is possible, the perceived discrepancy between desire for change and feelings of hopelessness about accomplishing change is likely to result in continued sustain talk and no change. When clients express confidence in their ability to change, they are more likely to engage in behavior change (Romano & Peters, 2016).

Because self-efficacy is a critical component of behavior change, it is crucial that you also believe in clients’ capacity to reach their goals. You can help clients strengthen hope and confidence in MI by evoking confidence talk. Here are two strategies for evoking confidence talk (Miller & Rollnick, 2013):

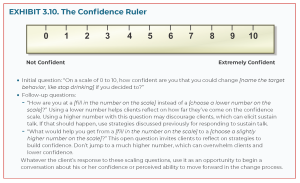

Use the Confidence Ruler (Exhibit 3.10) and scaling questions to assess clients’ confidence level and evoke confidence talk.

COUNSELOR NOTE: SELF-EFFICACY

Self-efficacy is a person’s confidence in his or her ability to change a behavior (Miller & Rollnick, 2013), such as a behavior that risks one’s health. Research has found that MI is effective in enhancing a client’s self-efficacy and positive outcomes including treatment completion, lower substance use at the end of treatment, greater desire to quit cannabis use, and reductions in risky sexual behavior for someone with HIV (Caviness et al., 2013; Chariyeva et al., 2013; Dufett, & Ward, 2015; Moore, Flamez,, & Szirony, 2017).

Ask open questions that evoke client strengths and abilities. Follow the open questions with reflective listening responses. Here are some examples of open questions that elicit confidence talk:

- “Knowing yourself as well as you do, how do you think you could [name the target behavior change, like cutting back on smoking marijuana]?”

- “How have you made difficult changes in the past?”

- “How could you apply what you learned then to this situation?”

- “What gives you confidence that you could [name the target behavior change, like stopping cocaine use]?”

In addition, you can help enhance clients’ hope and confidence about change by:

- Exploring clients’ strengths and brainstorming how to apply those strengths to the current situation.

- Giving information via EPE about the efficacy of treatment to increase clients’ sense of self-efficacy.

- Discussing what worked and didn’t work in previous treatment episodes and offering change options based on what worked before.

- Describing how people in similar situations have successfully changed their behavior. Other clients in treatment can serve as role models and offer encouragement.

- Offering some cognitive tools, like the AA slogan “One day at a time” or “Keep it simple” to break down an overwhelming task into smaller changes that may be more manageable.

- Educating clients about the biology of addiction and the medical effects of substance use to alleviate shame and instill hope that recovery is possible.

Engaging, focusing, and evoking set the stage for mobilizing action to change. During these MI processes, your task is to evoke DARN change talk. This moves the client along toward taking action to change substance use behaviors. At this point, your task is to evoke and respond to CAT change talk.

Recognizing signs of readiness to change

As you evoke and respond to DARN change talk, you will begin to observe these signs of readiness to change in the client’s statements (Miller & Rollnick, 2013):

- Increased change talk: As DARN change talk increases, commitment and activation change talk begin to be expressed. The client may show optimism about change and an intention to change.

- Decreased sustain talk: As change talk increases, sustain talk decreases. When change talk overtakes sustain talk, it is a sign that the client is moving toward change.

- Resolve: The client seems more relaxed. The client talks less about the problem, and sometimes expresses a sense of resolution.

- Questions about change: The client asks what to do about the problem, how people change if they want to, and so forth. For example: “What do people do to get off pain pills?”

- Envisioning: The client begins to talk about life after a change, anticipate difficulties, or discuss the advantages of change. Envisioning requires imagining something different—not necessarily how to get to that something different, but simply imagining how things could be different.

- Taking steps: The client begins to experiment with small steps toward change (e.g., going to an AA meeting, going without drinking for a few days, reading a self-help book). Affirming small change steps helps the client build self-efficacy and confidence.

When you notice these signs of readiness to change, it is a good time to offer the client a recapitulation summary in which you restate his or her change talk and minimize reflections of sustain talk. The recapitulation summary is a good way to transition into asking key questions (Miller & Rollnick, 2013).

Asking key questions

To help a client move from preparing to mobilizing for change, ask key questions (Miller & Rollnick, 2013):

-

- “What do you think you will do about your drinking?”

- “After reviewing the situation, what’s the next step for you?”

- “What do you want to do about your drug use?”

- “What can you do about your smoking?”

- “Where do you go from here?”

- “What might you do next?”

When the client responds with change talk (e.g., “I intend to stop using heroin”), you can move forward to the planning process. If the client responds with sustain talk (e.g., “It would be too hard for me to quit using heroin right now”), you should go back to the evoking process. Remember that change is not a linear process for most people.

Do not jump into the planning process if the client expresses enough sustain talk to indicate not being ready to take the next step. The ambivalence about taking the next step may be uncertainty about giving up the substance use behavior or a lack of confidence about being able to make the change.

Planning

Your task in the process is to help the client develop a change plan that is acceptable, accessible, and appropriate. Once a client decides to change a substance use behavior, he or she may already have ideas about how to make that change. For example, a client may have previously stopped smoking cannabis and already knows what worked in the past. Your task is to simply reinforce the client’s plan.

Don’t assume that all clients need a structured method to develop a change plan. Many people can make significant lifestyle changes and initiate recovery from SUDs without formal assistance (Kelly, Bergman, Hoeppner, Vilsaint, & White, 2017). For clients who need help developing a change plan, remember to continue using MI techniques and OARS to move the process from why change and what to change to how to change (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). A change plan is like a treatment plan, but broader (e.g., going to an addiction treatment program may be part of a change plan), and the client, rather than you or the treatment program, is the driver of the planning process (Miller & Rollnick, 2013).

Identifying a change goal

Part of planning is working with the client to identify or clarify a change goal. At this point, the client may have identified a change goal. For example, when you ask a key question such as “What do you want to do about the drinking?” the client might say, “I want to cut back to two drinks a day on weekends.” In this situation, the focus shifts to developing a plan with specific steps the client might take to reach the change goal. If the client is vague about a change goal and says, “I really need to do something about my drinking,” the first step is to help the client clarify the change goal.

Here is an example of a dialog that helps the client get more specific:

Counselor: You are committed to making some changes to your drinking. (Reflection) What would that look like? (Open question)

Client: Well, I tried to cut back to one drink a day, but all I could think about was going to the bar and getting drunk. I cut back for 2 days but did end up back at the bar, and then it just got worse from there. At this point, I don’t think I can just cut back.

Counselor: You made a good-faith effort to control the drinking and learned a lot from that experiment. (Affirmation) You now think that cutting back is probably not a good strategy for you. (Reflection)

Client: Yeah. It’s time to quit. But I’m not sure I can do that on my own.

Counselor: You’re ready to quit drinking completely and realize that you could use some help with making that kind of change. (Reflection)

Client: Yeah. It’s time to give it up.

Counselor: Let’s review the conversation, (Summarization) and then talk about next steps.

The counselor uses OARS to help the client clarify the change goal. The counselor also hears that the client lacks confidence that he or she can achieve the change goal and reinforces the client’s desire for some help in making the change. The next step with this client is to develop a change plan.

Developing a change plan

Begin with the change goal identified by the client, then explore specific steps the client can take to achieve it. In the planning process, use OARS and pay attention to CAT change talk. As you proceed, carefully note the shift from change talk that is more general to change talk that is specific to the change plan (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). Some evidence shows that change talk is related to the completion of a change plan (Roman & Peters, 2016).

Here are some strategies for helping clients develop a change plan (Miller & Rollnick, 2013):

- Confirm the change goal. Make sure that you and the client agree on what substance use behavior the client wants to change and what the ultimate goal is (e.g., to cut back or to abstain). This goal might change as the client takes steps to achieve it. For example, a client who tries to cut back on cannabis use may find that that it is not a workable plan and may decide to abstain completely.

- Elicit the client’s ideas about how to change. There may be many different pathways to achieve the desired goal. For example, a client whose goal is to stop drinking may go to AA or SMART Recovery meetings for support, get a prescription for naltrexone (a medication that reduces craving and the pleasurable effects of alcohol [Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration & National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2015]) from a primary care provider, enter an intensive outpatient treatment program, or try some combination of these. Before you jump in with your ideas, elicit the client’s ideas about strategies to make the change. Explore pros and cons of the client’s ideas; determine which appeals to the client most and is most appropriate for this client.

- Offer a menu of options. Use the EPE process (see the section “Developing discrepancy: A values conversation” above) to ask permission to offer suggestions about accessible treatment options, provide information about those options, and elicit the client’s understanding of options and which ones seem acceptable.

- Summarize the change plan. Once you and the client have a clear plan, summarize the plan and the specific steps or pathways the client has identified. Listen for CAT change talk and reinforce it through reflective listening.

- Explore obstacles. Once the client applies the change plan to his or her life, there will inevitably be setbacks. Try to anticipate potential obstacles and how the client might respond to them before the client takes steps to implement the plan. Then reevaluate the change plan, and help the client tweak it using the information about what did and didn’t work from prior attempts.

Strengthening Commitment to Change

The planning process is just the beginning of change. Clients must commit to the plan and show that commitment by taking action. There is some evidence that client commitment change talk is associated with positive AUD outcomes (Romano & Peters, 2016). One study found that counselor efforts to elicit client commitment to change alcohol use is associated with reduced alcohol consumption and increased abstinence for clients in outpatient treatment (Magill, Stout, & Apodoaca, 2013).

Usually, people express an intention to make a change before they make a firm commitment to taking action. You can evoke the client’s intention to take action by asking open questions: “What are you willing to do this week?” or “What specific steps of the change plan are you ready to take?” (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). Remember that the client may have an end goal (e.g., to quit drinking) and intermediate action steps to achieving that goal (e.g., filling a naltrexone prescription, going to an AA meeting).

Once the client has expressed an intention to change, elicit commitment change talk. Try asking an open question that invites the client to explore his or her commitment more clearly: “What would help you strengthen your commitment to ________________ [name the step or ultimate goal for change, for example, getting that prescription from your doctor for naltrexone]?” (Miller & Rollnick, 2013).

Other strategies to strengthen commitment to action steps and change goals include (Miller & Rollnick, 2013):

- Exploring any ambivalence clients have about change goals or specific elements of change plans.

- Reinforcing CAT change talk through reflective listening.

- Inviting clients to state their commitment to their significant others.

- Asking clients to self-monitor by recording progress toward change goals (e.g., with a drinking log).

- Exploring, with clients’ consent, whether supportive significant others can help with medication adherence or other activities that reinforce commitment (e.g., getting to AA meetings).

The change plan process lends itself to using other counseling methods like CBT and MET. For example, you can encourage clients to monitor their thoughts and feelings in high-risk situations where they are more likely to return to substance use or misuse. No matter what counseling strategies you use, keep to the spirit of MI by working with clients and honoring and respecting their right to and capacity for self-direction.

Benefits of MI in Treating SUDs

The number of research studies on MI has doubled about every 3 years from 1999 to 2013 (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). Many studies were randomized clinical trials reflecting a range of clinical populations, types of problems, provider settings, types of SUDs, and co-occurring substance use and mental disorders (Smedslund et al., 2011).

Although some studies report mixed results, the overall scientific evidence suggests that MI is associated with small to strong (and significant) effects for positive substance use behavioral outcomes compared with no treatment. MI is as effective as other counseling approaches (DiClemente et al., 2017). A research review found strong, significant support for MI and combined MI/MET in client outcomes for alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis, and some support for its use in treating cocaine and combined illicit drug use disorders (DiClemente et al., 2017). Positive outcomes included reduced alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis use; fewer alcohol-related problems; and improved client engagement and retention (DiClemente et al., 2017). MI and combined MI/MET were effective with adolescents, young adults, college students, adults, and pregnant women.

Counselor adherence to MI skills is important for producing client outcomes (Apodaca et al., 2016; Magill et al., 2013). For instance, using open questions, simple and complex reflective listening responses, and affirmations is associated with change talk (Apodaca et al., 2016; Romano & Peters, 2016). Open questions and reflective listening responses can elicit sustain talk when counselors explore ambivalence with clients (Apodaca et al., 2016). However, growing evidence suggests that the amount and strength of client change talk versus sustain talk in counseling sessions are key components of MI associated with behavior change (Gaume et al., 2016; Houck et al., 2018; Lindqvist et al., 2017; Magill et al., 2014).

Other benefits of MI include (Miller & Rollnick, 2013):

- Cost effectiveness. MI can be delivered in brief interventions like SBIRT (screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment) and FRAMES (Feedback, Responsibility, Advice, Menu of options, Empathy, and Self-efficacy), which makes it cost effective. In addition, including significant others in MI interventions is also cost effective (Shepard et al., 2016).

- Ease of use. MI has been adapted and integrated into many settings, including primary care facilities, emergency departments, behavioral health centers, and criminal justice and social service agencies. It is useful anywhere that focuses on helping people manage substance misuse and SUDs.

- Broad dissemination. MI has been disseminated throughout the United States and internationally.

- Applicability to diverse health and behavioral health problems. Beyond substance use behaviors, MI has demonstrated benefits across a wide range of behavior change goals.

- Effectiveness. Positive effects from MI counseling occur across a range of real-life clinical settings.

- Ability to complement other treatment approaches. MI fits well with other counseling approaches, such as CBT. It can enhance client motivation to engage in specialized addiction treatment services and stay in and adhere to treatment.

- Ease of adoption by a range of providers. MI can be implemented by primary care and behavioral health professionals, peer providers, criminal justice personnel, and various other professionals.

- Role in mobilizing client resources. MI is based on person-centered counseling principles. It focuses on mobilizing the client’s own resources for change. It is consistent with the healthcare model of helping people learn to self-manage chronic illnesses like diabetes and heart disease.

Conclusion

MI is a directed, person-centered counseling style that is effective in helping clients change their substance use behaviors. When delivered in the spirit of MI, the core skills of asking open questions, affirming, using reflective listening, and summarizing enhance client motivation and readiness to change. Counselor empathy, shown through reflective listening and evoking change talk, is another important element of MI’s effectiveness and is associated with positive client outcomes. MI has been adapted for use in brief interventions and across a wide range of clinical settings and client populations. It is compatible with other counseling models and theories of change, including CBT and the SOC.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Enhancing Motivation for Change in Substance Use Disorder Treatment. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series No. SAMHSA Publication No. PEP19-02-01-003. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019.

Group Counseling Skills

Although not every client will be appropriate for group counseling, it remains the modality of choice for treating addiction. Group counseling has many benefits including, but not limited to, the following:

- Cost-effectiveness

- Peer-support and sense of community

- Development of social and interpersonal skills

- Ability to learn effective confrontation skills

- Ability to receive feedback from various perspectives

Given the importance of group counseling in treating addiction, it is imperative that counselors working in the field learn and develop the skills necessary to effectively facilitate various types of groups used in treatment settings. Therapeutic groups used in the treatment of addiction include (Substance Abuse Treatment: Group Therapy, 2015):

- Psychoeducational groups, which teach about substance abuse

- Skills development groups, which hone the skills necessary to break free of addiction

- Cognitive-behavioral groups, which rearrange patterns of thinking and action that lead to addiction

- Support groups, which comprise a forum where members can debunk each other’s excuses and support constructive change

- Interpersonal process group psychotherapy (often referred to as “therapy groups”), which enable clients to recreate their pasts in the here-and-now of group and rethink the relational and other life problems that they have previously fled by means of addictive substances

treatment improvement protocol 41 / Substance abuse treatment: group therapy (adaptation)

the Group Leader