31 Chapter 25: Navigating Cultural Awareness & Diversity Issues

Cultural Awareness

Learning about each others differences will allow you to feel more comfortable when you interact with peers, staff, and faculty that are different than you. Enhancing your cultural awareness will enrich your educational experience, improve your communication, and when presented with opportunities to critically explore these differences, you can become more accepting of others.

The information in this chapter is designed to better prepare students for the intellectual and societal challenges facing an increasingly diverse society.

Life in Quarantine

Since March 2020, the world has been turned upside down due to the covid-19 pandemic. The Life in Quarantine Project has invited people from all over the globe to share their personal stories about how the pandemic has affected them. To read about others’ experiences and share your own story, please see: http://liqproject.org/archive/.

Where Are You From?

Think about the question “where are you from?” What does it imply? Is it home? Is it where someone was born? Is it where their parents were born? Their grandparents? Is where someone is “from” connected with where they live? Have you ever assumed that someone of a certain ethnic background might come from a certain region?

Definitions of Cultural Competence

Cultural competence is the social awareness that everyone is unique, that different cultures and backgrounds affect how people think and behave, and that this awareness allows people to behave appropriately and perform effectively in culturally diverse environments.

Cultural competence is a set of congruent behaviors, attitudes and policies that come together in a system, agency or among professionals and enable that system, agency or those professions to function effectively. Five essential elements contribute to a system’s, institution’s, or agency’s ability to become more culturally competent which include:

- Valuing diversity

- Having the capacity for cultural self-assessment

- Being conscious of the dynamics inherent when cultures interact

- Having institutionalized culture knowledge

- Having developed adaptations to service delivery reflecting and understanding of cultural diversity

These five elements should be manifested at every level of an organization including policy making, administrative, and practice. Further these elements should be reflected in the attitudes, structures, policies and services of the organization[1].

As a college student, you are likely to find yourself in diverse classrooms, organizations, and – eventually – workplaces. It is important to prepare yourself to be able to adapt to diverse environments. Cultural competency can be defined as the ability to recognize and adapt to cultural differences and similarities. It involves “(a) the cultivation of deep cultural self-awareness and understanding (i.e., how one’s own beliefs, values, perceptions, interpretations, judgments, and behaviors are influenced by one’s cultural community or communities) and (b) increased cultural other-understanding (i.e., comprehension of the different ways people from other cultural groups make sense of and respond to the presence of cultural differences).”1

In other words, cultural competency requires you to be aware of your own cultural practices, values, and experiences, and to be able to read, interpret, and respond to those of others. Such awareness will help you successfully navigate the cultural differences you will encounter in diverse environments. Cultural competency is critical to working and building relationships with people from different cultures; it is so critical, in fact, that it is now one of the most highly desired skills in the modern workforce.2

Cultural Quotient (CQ)

Cultural Quotient (CQ) helps us understand and communicate with people from other cultures effectively. It is one’s ability to recognize cultural differences through knowledge and mindfulness, and behave appropriately when facing people from other cultures. Mindful is defined as being conscious or aware of something. The cultural intelligence approach goes beyond this emphasis on knowledge because it also emphasizes the importance of developing an overall repertoire of understanding, motivation, and skills that enables one to move in and out of lots of different cultural contexts[2].

Due to the globalization of our world, people of different cultures today live together in communities across our many nations. This presents more opportunities to interact with diverse individuals in many facets and thus, today’s workforce would need to know the customs and worldviews of other cultures. Therefore, people with a higher CQ can better interact with people from other cultures easily and more effectively.

Rationale for Curriculum Inclusion

Our country and our workplace settings are becoming more and more culturally diverse. Additionally, interaction with individuals and groups from other countries and cultures either face-to-face or in virtual contexts is more commonplace than ever. Effective working relationships provide for productive outcomes (e.g., products, services). For college students to be successful in their future careers, it is necessary that they be exposed to others who are culturally diverse and that they engage in discussions and activities that help them not only effectively function in those settings but actively contribute to those positive and productive outcomes.

Sample scenarios:

Matt’s case:

Matt is participating in a student exchange program in Japan. He loves to eat doughnuts or pancakes for breakfast. However, his host-family usually has a traditional Japanese breakfast (e.g., rice, miso-soup, pickles, egg dish, and/or broiled fish) with chopsticks. He is learning and getting better at using chopsticks. However, he doesn’t feel like having soup or fish for breakfast. One day when he went to a grocery store with Sachi, his host-mom, he found a doughnuts section. Matt suggested that they have doughnuts for breakfast. Sachi was surprised and said, “We can have doughnuts as a snack, but not for breakfast. They are too sweet for breakfast.”

Cultural norms influence when, how, and what we eat.

Kate’s case:

Kate is a first-generation college student from a rural area of Kentucky.

When she came to college, she was surprised to see many foreign-born students and faculty/staff on campus. One of her class instructors is not a native English speaker, and he has a thick foreign accent. At first she was shocked because she could hardly understand her teacher. However, when she paid more attention to what he said, she found out that his English was not bad. She actually got used to his accent during the first week of classes.

One day, Kate met Tim from Boston, Massachusetts. Unfortunately, she sometimes could not understand what he said because of his Boston accent. When she politely mentioned his accent, he laughed and pointed out that she has a Southern accent. He seems to be a nice person, but she feels that he is too direct.

How we speak and what kind of accent we have is determined by our experience (i.e, where we grew up and by whom we were raised, etc.).

In the following video, representatives from Rutgers University Behavioral Health Care elaborate on the concept of cultural competency:

Video: Cultural Competency at Rutgers University Behavioral Health Care

We don’t automatically understand differences among people and celebrate the value of those differences. Cultural competency is a skill that you can learn and improve upon over time and with practice. What actions can you take to build your cultural competency skills?

- Acknowledge your own uniqueness, for you are diverse, too. Diversity doesn’t involve just other people. Consider that you may be just as different to other people as they are to you. Don’t think of the other person as being the one who is different, that you are somehow the “norm.” Your religion may seem just as odd to them as theirs does to you, and your clothing may seem just as strange looking to them as theirs is to you—until you accept there is no one “normal” or right way to be. Look at yourself in a mirror and consider why you look as you do. Why do you use the slang you do with your friends? Why did you just have that type of food for breakfast? How is it that you prefer certain types of music? Read certain books? Talk about certain things? Much of this has to do with your cultural background—so it makes sense that someone from another cultural or ethnic background is different in some ways. But both of you are also individuals with your own tastes, preferences, ideas, and attitudes—making you unique. It’s only when you realize your own uniqueness that you can begin to understand and respect the uniqueness of others, too.

- Consider your own (possibly unconscious) stereotypes. A stereotype is a fixed, simplistic view of what people in a certain group are like. It is often the basis for prejudice and discrimination: behaving differently toward someone because you stereotype them in some way. Stereotypes are generally learned and emerge in the dominant culture’s attitudes toward those from outside that dominant group. A stereotype may be explicitly racist and destructive, and it may also be a simplistic generalization applied to any group of people, even if intended to be flattering rather than negative. As you have read this chapter so far, did you find yourself thinking about any group of people, based on any kind of difference, and perhaps thinking in terms of stereotypes? If you walked into a party and saw many different kinds of people standing about, would you naturally avoid some and move toward others? Remember, we learn stereotypes from our cultural background—so it’s not a terrible thing to admit you have inherited some stereotypes. Thinking about them is a first step in breaking out of these irrational thought patterns.

- Do not try to ignore differences among people. Some people try so hard to avoid stereotyping that they go to the other extreme and try to avoid seeing any differences at all among people. But as we have seen throughout this chapter, people are different in many ways, and we should accept that if we are to experience the benefits of diversity.

- Don’t apply any group generalizations to individuals. As an extension of not stereotyping any group, also don’t think of any individual person in terms of group characteristics. People are individuals first, members of a group second, and any given generalization simply may not apply to an individual. Be open-minded and treat everyone with respect as an individual with his or her own ideas, attitudes, and preferences.

- Develop cultural sensitivity for communication. Realize that your words may not mean quite the same thing in different cultural contexts or to individuals from different backgrounds. This is particularly true of slang words, which you should generally avoid until you are sure the other person will know what you mean. Never try to use slang or expressions you think are common in the cultural group of the person you are speaking with. Similarly, since body language often varies among different cultures, avoid strong gestures and expressions until the responses of the other person signify he or she will not misinterpret the messages sent by your body language.

- Take advantage of campus opportunities to increase your cultural awareness. Your college likely has multiculturalism courses or workshops you can sign up for. Special events, cultural fairs and celebrations, concerts, and other programs are held frequently on most campuses. There may also be opportunities to participate in group travel to other countries or regions of cultural diversity.

- Take the initiative in social interactions. Many students just naturally hang out with other students they are most like—that almost seems to be part of human nature. Even when we’re open-minded and want to learn about others different from ourselves, it often seems easier and more comfortable to interact with others of the same age, cultural group, and so on. If we don’t make a small effort to meet others, however, we miss a great opportunity to learn and broaden our horizons. Next time you’re looking around the classroom or dorm for someone to ask about a class you missed or to study together for a test or group project, choose someone different from you in some way. Making friends with others of different backgrounds is often one of the most fulfilling experiences of college students.

- Work through conflicts as in any other interaction. Conflicts simply occur among people, whether of the same or different background. If you are afraid of making a mistake when interacting with someone from a different background, you might avoid interaction altogether—and thus miss the benefits of diversity. Nothing risked, nothing gained. If you are sincere and respect the other, there is less risk of a misunderstanding occurring. If a conflict does occur, work to resolve it as you would any other tension with another person.

Developing your cultural competency will help you be more in tune with the cultural nuances and differences present in any situation. It is also the first step in being able to appreciate the benefits diversity can bring to a situation.

This video portrays assumptions and expectations some people have about having their DNA tested. How do you think it ties into cultural competency?

Video: The DNA Journey

Exercise

DEVELOPING YOUR CULTURAL COMPETENCY

Objective

- Define and apply principles of cultural competency

Instructions

This activity will help you examine ways in which you can develop your awareness of and commitment to diversity on campus. Answer the following questions to the best of your ability:

- What are my plans for expanding myself personally and intellectually in college?

- What kind of community will help me expand most fully, with diversity as a factor in my expansion?

- What are my comfort zones, and how might I expand them to connect with more diverse groups?

- Do I want to be challenged by new viewpoints, or will I feel more comfortable connecting with people who are like me?

- What are my biggest questions about diversity?

Consider the following strategies to help you answer the questions:

- Examine extracurricular activities. Can you get involved with clubs or organizations that promote and expand diversity?

- Review your college’s curriculum. In what ways does it reflect diversity? Does it have departments and courses on historically unrepresented peoples, e.g., cultural and ethnic studies, and gender and sexuality studies. Look for study-abroad programs, as well.

- Read your college’s mission statement. Read the mission statement of other colleges. How do they match up with your values and beliefs? How do they align with the value of diversity?

- Inquire with friends, faculty, colleagues, family. Be open about diversity. What does it mean to others? What positive effects has it had on them? Ask people about diversity.

- Research can help. You might consult college literature, Web sites, resource centers and organizations on campus, etc.

The multiple roles we play in life—student, sibling, employee, partner, roommate, for example—are only a partial glimpse into our identity. Right now, you may think, “I really don’t know what I want to be,” meaning you do not know what you want to do for a living, but have you ever tried to define yourself in terms of the sum of your parts?

Social roles are those identities we assume in relationship to others. Our social roles tend to shift based on where we are and who we are with. Considering your social roles as well as your nationality, ethnicity, race, friends, gender, sexuality, beliefs, abilities, geography, etc., who are you?

According to the American Psychological Association, personal identity is an individual’s sense of self defined by (a) a set of physical, psychological, and interpersonal characteristics that is not wholly shared with any other person and (b) a range of affiliations (e.g., ethnicity) and social roles. Your identity is tied to the most dominant aspects of your background and personality.5 It determines the lens through which you see the world and the lens through which you receive information.

ACTIVITY

Complete the following statement using no more than four words:

I am _______________________________.

It is difficult to narrow down our identity to just a few options. One way to complete the statement would be to use gender and geography markers. For example, “I am a male New Englander” or “I am an American woman.” Assuming they are true, no one can argue against those identities, but do those statements represent everything or at least most things that identify the speakers? Probably not.

Try finishing the statement again by using as many words as you wish.

I am ____________________________________.

If you ended up with a long string of descriptors that would be hard for a new acquaintance to manage, don’t worry. Our identities are complex and reflect that we lead interesting and multifaceted lives.

To better understand identity, consider how social psychologists describe it. Social psychologists, those who study how social interactions take place, often categorize identity into four types: personal identity, role identity, social identity, and collective identity.

Personal identity captures what distinguishes one person from another based-on life experiences. No two people, even identical twins, live the same life.

Role identity defines how we interact in certain situations. Our roles change from setting to setting, and so do our identities. At work you may be a supervisor, in the classroom you are a peer working collaboratively; at home, you may be the parent of a 10-year-old. In each setting, your bubbly personality may be the same, but how your coworkers, classmates, and family see you is different.

Social identity shapes our public lives by our awareness of how we relate to certain groups. For example, an individual might relate to or “identify with” Korean Americans, Chicagoans, Methodists, and Bulls fans. These identities influence our interactions with others. Upon meeting someone, for example, we look for connections as to how we are the same or different. Our awareness of who we are makes us behave a certain way in relation to others. If you identify as a hockey fan, you may feel an affinity for someone else who also loves the game.

Collective identity refers to how groups form around a common cause or belief. For example, individuals may bond over similar political ideologies or social movements. Their identity is as much a physical formation as a shared understanding of the issues they believe in. For example, many people consider themselves part of the collective energy surrounding the #metoo movement. Others may identify as fans of a specific type of entertainment such as Trekkies, fans of the Star Trek series.

What we do and believe today may not be the same tomorrow. Further, at any one moment, the identities we claim may seem at odds with each other. Shifting identities are a part of personal growth. While we are figuring out who we truly are and what we believe, our sense of self and the image that others have of us may be unclear or ambiguous.

Many people are uncomfortable with identities that do not fit squarely into one category. How do you respond when someone’s identity or social role is unclear? Such ambiguity may challenge your sense of certainty about the roles that we all play in relationship to one another. Racial, ethnic, and gender ambiguity can challenge some people’s sense of social order and social identity.

When we force others to choose only one category of identity (race, ethnicity, or gender, for example) to make ourselves feel comfortable, we do a disservice to the person who identifies with more than one group. For instance, people with multiracial ancestry are often told that they are too much of one and not enough of another.

The actor Keanu Reeves has a complex background. He was born in Beirut, Lebanon, to a White English mother and a father with Chinese-Hawaiian ancestry. His childhood was spent in Hawaii, Australia, New York, and Toronto. Reeves considers himself Canadian and has publicly acknowledged influences from all aspects of his heritage. Would you feel comfortable telling Keanu Reeves how he must identify racially and ethnically?

There is a question many people ask when they meet someone whom they cannot clearly identify by checking a specific identity box. Inappropriate or not, you have probably heard people ask, “What are you?” Would it surprise you if someone like Keanu Reeves shrugged and answered, “I’m just me”?

Malcom Gladwell is an author of five New York Times best-sellers and is hailed as one of Foreign Policy’s Top Global Thinkers. He has spoken on his experience with identity as well. Gladwell has a Black Jamaican mother and a White Irish father. He often tells the story of how the perception of his hair has allowed him to straddle racial groups. As long as he kept his hair cut very short, his fair skin obscured his Black ancestry, and he was most often perceived as White. However, once he let his hair grow long into a curly Afro style, Gladwell says he began being pulled over for speeding tickets and stopped at airport check-ins. His racial expression carried serious consequences.

Avoid Making Assumptions

By now you should be aware of the many ways diversity can be both observable and less apparent. Based on surface clues, we may be able to approximate someone’s age, weight, and perhaps their geographical origin, but even with those observable characteristics, we cannot be sure about how individuals define themselves. If we rely too heavily on assumptions, we may be buying into stereotypes, or generalizations.

Stereotyping robs people of their individual identities. If we buy into stereotypes, we project a profile onto someone that probably is not true. Prejudging people without knowing them, better known as prejudice or bias, has consequences for both the person who is biased and the individual or group that is prejudged. In such a scenario, the intimacy of real human connections is lost. Individuals are objectified, meaning that they only serve as symbolic examples of who we assume they are instead of the complex, intersectional individuals we know each person to be.

Stereotyping may be our way of avoiding others’ complexities. When we stereotype, we do not have to remember distinguishing details about a person. We simply write their stories for ourselves and let those stories fulfill who we expect those individuals to be. For example, a hiring manager may project onto an Asian American the stereotype of being good at math and hire her as a researcher over her Hispanic counterpart. Similarly, an elementary school teacher may recruit an Indian American sixth grader to the spelling bee team because many Indian American students have won national tournaments in the recent past. A real estate developer may hire a gay man as an interior designer because he has seen so many gay men performing this job on television programs. A coach chooses a White male student to be a quarterback because traditionally, quarterbacks have been White men. In those scenarios, individuals of other backgrounds, with similar abilities, may have been overlooked because they do not fit the stereotype of who others suspect them to be.

Earlier, equity and inclusion were discussed as going hand in hand with achieving civility and diversity. In the above scenarios, equity and inclusion are needed as guiding principles for those with decision-making power who are blocking opportunity for nontraditional groups. Equity might be achieved by giving a diverse group of people access to internships to demonstrate their skills. Inclusion might be achieved by assembling a hiring or recruiting committee that might have a better chance of seeing beyond stereotypical expectations.

Being civil and inclusive does not require a deep-seated knowledge of the backgrounds and perspectives of everyone you meet. That would be impossible. But avoiding assumptions and being considerate will build better relationships and provide a more effective learning experience. It takes openness and self-awareness and sometimes requires help or advice but learning to be sensitive—practicing assumption avoidance—is like a muscle you can strengthen.

Be Mindful of Microaggressions

Whether we mean to or not, we sometimes offend people by not thinking about what we say and the way we say it. One danger of limiting our social interactions to people who are from our own social group is in being insensitive to people who are not like us. The term microaggression refers to acts of insensitivity that reveal our inherent biases, cultural incompetency, and hostility toward someone outside of our community. Those biases can be toward race, gender, nationality, or any other diversity variable. The individual on the receiving end of a microaggression is reminded of the barriers to complete acceptance and understanding in the relationship. Let us consider an example.

Ann is new to her office job. Her colleagues are friendly and helpful, and her first two months have been promising. She uncovered a significant oversight in a financial report, and, based on her attention to detail, was put on a team working with a large client. While waiting in line at the cafeteria one day, Ann’s new boss overhears her laughing and talking loudly with some colleagues. He then steps into the conversation, saying, “Ann, this is not a night at one of your clubs. Quiet down.” As people from the nearby tables look on, Ann is humiliated and angered.

What was Ann’s manager implying? What could he have meant by referring to “your clubs?” How would you feel if such a comment were openly directed at you? One reaction to this interaction might be to say, “So what? Why let other people determine how you feel? Ignore them.” While that is certainly reasonable, it may ignore the pain and invalidation of the experience. And even if you could simply ignore some of these comments, there is a compounding effect of being frequently, if not constantly, barraged by such experiences.

Consider the table below, which highlights common examples of microaggressions. In many cases, the person speaking these phrases may not mean to be offensive. In fact, in some cases the speaker might think they are being nice. However, appropriate terminology and other attitudes or acceptable descriptions change all the time. Before saying something, consider how a person could take the words differently than you meant them.

Microaggressions

| Category | Microaggression | Why It’s Offensive |

| Educational Status or Situation | “You’re an athlete; you don’t need to study.” | Stereotypes athletes and ignores their hard work. |

| “You don’t get financial aid; you must be rich. | Even an assumption of privilege can be invalidating. | |

| “Did they have honors classes at your high school?” | Implies that someone is less prepared or intelligent based on their geography. | |

| Race, Ethnicity, National Origin | “You speak so well for someone like you.” | Implies that people of a certain race/ethnicity can’t speak well. |

| “No, where are you really from?” | Calling attention to someone’s national origin makes them feel separate. | |

| “You must be good at _____.” | Falsely connects identity to ability. | |

| “My people had it so much worse than yours did.” | Makes assumptions and diminishes suffering/difficulty. | |

| “I’m not even going to try your name. It looks too difficult.” | Dismisses a person’s culture and heritage. | |

| “It’s so much easier for Black people to get into college.” | Assumes that merit is not the basis for achievement. | |

| Gender and Gender Identity | “They’re so emotional.” | Assumes a person cannot be emotional and rational. |

| “I guess you can’t meet tonight because you have to take care of your son?” | Assumes a parent (of any gender) cannot participate. | |

| “I don’t get all this pronoun stuff, so I’m just gonna call you what I call you.” | Diminishes the importance of gender identity; indicates a lack of empathy. | |

| “I can’t even tell you used to be a woman.” | Conflates identity with appearance, and assumes a person needs someone else’s validation. | |

| “You’re too good-looking to be so smart.” | Connects outward appearance to ability. | |

| Sexual Orientation | “I support you; just don’t throw it in my face.” | Denies another person’s right to express their identity or point of view. |

| “You seem so rugged for a gay guy.” | Stereotypes all gay people as being “not rugged,” and could likely offend the recipient. | |

| “I might try being a lesbian.” | May imply that sexual orientation is a choice. | |

| “I can’t even keep track of all these new categories.” | Bisexual, pansexual, asexual, and other sexual orientations are just as valid and deserving of respect as more binary orientations. | |

| “You can’t just love whomever you want; pick one.” | Bisexual, pansexual, asexual, and other sexual orientations are just as valid and deserving of respect as more binary orientations. | |

| Age | “Are you going to need help with the software?” | May stereotype an older person as lacking experience with the latest technology. |

| “Young people have it so easy nowadays.” | Makes a false comparison between age and experience. | |

| “Okay, boomer.” | Dismisses an older generation as out of touch. | |

| Size | “I bet no one messes with you.” | Projects a tendency to be aggressive onto a person of large stature. |

| “You are so cute and tiny.” | Condescending to a person of small stature. | |

| “I wish I was thin and perfect like you.” | Equates a person’s size with character. | |

| Ability | (To a person using a wheelchair) “I wish I could sit down wherever I went.” | Falsely assumes a wheelchair is a luxury; minimizes disabilities. |

| “You don’t have to complete the whole test. Just do your best.” | Assumes that a disability means limited intellectual potential. | |

| “I’m blind without my glasses.” | Equating diminished capacity with a true disability. |

Have you made statements like these, perhaps without realizing the offense they might cause? Some of these could be intended as compliments, but they could have the unintended effect of diminishing or invalidating someone. (Credit: Modification of work by Derald Wing Sue6.)

Everyone Has a Problem: Implicit Bias

One reason we fall prey to stereotypes is our own implicit bias. Jo Handelsman and Natasha Sakraney, who developed science and technology policy during the Obama administration, defined implicit bias.

According to Handelsman and Sakraney, “A lifetime of experience and cultural history shapes people and their judgments of others. Research demonstrates that most people hold unconscious, implicit assumptions that influence their judgments and perceptions of others. Implicit bias manifests in expectations or assumptions about physical or social characteristics dictated by stereotypes that are based on a person’s race, gender, age, or ethnicity. People who intend to be fair, and believe they are egalitarian, apply biases unintentionally. Some behaviors that result from implicit bias manifest in actions, and others are embodied in the absence of action; either can reduce the quality of the workforce and create an unfair and destructive environment.”7

The notion of bias being “implicit,” or unconsciously embedded in our thoughts and actions, is what makes this characteristic hard to recognize and evaluate. You may assume that you hold no racial bias, but messages from our upbringing, social groups, and media can feed us negative racial stereotypes no matter how carefully we select and consume information. Further, online environments have algorithms that reduce our exposure to diverse points of view. Psychologists generally agree that implicit bias affects the judgements we make about others.

the College Classroom

We carry our attitudes about gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, age, and other diversity categories with us wherever we go. The college classroom is no different than any other place. Both educators and students maintain their implicit bias and are sometimes made uncomfortable by interacting with people different than themselves. Take for example a female freshman who has attended a school for girls for six years before college. She might find being in the classroom with her new male classmates a culture shock and dismiss male students’ contributions to class discussions. Similarly, a homeschooled student may be surprised to find that no one on campus shares his religion. He may feel isolated in class until he finds other students of similar background and experience. Embedded in your classroom may be peers who are food insecure, undocumented, veterans, atheist, Muslim, or politically liberal or conservative. These identities may not be visible, but they still may separate and even marginalize these members of your community. If, in the context of classroom conversations, their perspectives are overlooked, they may also feel very isolated.

In each case, the students’ assumptions, previous experience with diversity of any kind, and implicit bias surface. How each student reacts to the new situation can differ. One reaction might be to self-segregate, that is, locate people they believe are like them based on how they look, the assumption being that those people will share the same academic skills, cultural interests, and personal values that make the student feel comfortable. The English instructor at the beginning of this chapter who assumed all his students were the same demonstrated how this strategy could backfire.

You do not have to be enrolled in a course related to diversity, such as Asian American literature, to be concerned about diversity in the classroom. Diversity touches all aspects of our lives and can enter a curriculum or discussion at any time because each student and the instructor bring multiple identities and concerns into the classroom. Ignoring these concerns, which often reveal themselves as questions, makes for an unfulfilling educational experience.

In higher education, diversity includes not only the identities we have discussed such as race and gender, but also academic preparation and ability, learning differences, familiarity with technology, part-time status, language, and other factors students bring with them. Of course, the instructor, too, brings diversity into the classroom setting. They decide how to incorporate diverse perspectives into class discussions, maintain rules of civility, choose inclusive materials to study or reference, receive training on giving accommodations to students who need them, and acknowledge their own implicit bias. If they are culturally competent, both students and instructors are juggling many concerns.

“I’m just me.”

Remember the response to the “What are you?” question for people whose racial or gender identity was ambiguous? “I’m just me” also serves those who are undecided about diversity issues or those who do not fall into hard categories such as feminist, liberal, conservative, or religious. Ambiguity sometimes makes others feel uncomfortable. For example, if someone states she is a Catholic feminist unsure about abortion rights, another student may wonder how to compare her own strong pro-life position to her classmate’s uncertainty. It would be much easier to know exactly which side her classmate is on. Some people straddle the fence on big issues, and that is OK. You do not have to fit neatly into one school of thought. Answer your detractors with “I’m just me,” or tell them if you genuinely do not know enough about an issue or are not ready to take a strong position.

Resources for expanding our understanding and inclusion of diversity issues are all around us.

Footnotes

- 6Adapted from Sue, Derald Wing, Microaggressions in Everyday Life: Race, Gender and Sexual Orientation, Wiley & Sons, 2010

- 7Handlesman, Jo and Sakraney, Natasha. White House Office of Science and Technology Policy. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/microsites/ostp/bias_9-14-15_final.pdf.

- 8WInslow, Barbara. “The Impact of Title IX.” Gilder-Lerhman Institute. https://faculty.uml.edu/sgallagher/The_Impact_of_Title_IX-_GilderLehrman.pdf

Gender

More and more, gender is also a diversity category that we increasingly understand to be less clearly defined. Some people identify themselves as gender fluid or non-binary. “Binary” refers to the notion that gender is only one of two possibilities, male or female. Fluidity suggests that there is a range or continuum of expression. Gender fluidity acknowledges that a person may vacillate between male and female identity.

Asia Kate Dillon is an American actor and the first non-binary actor to perform in a major television show with their roles on Orange is the New Black and Billions. In an article about the actor, a reporter conducting the interview describes his struggle with trying to describe Dillon to the manager of the restaurant where the two planned to meet. The reporter and the manger struggle with describing someone who does not fit a pre-defined notion of gender identity. Imagine the situation: You are meeting someone at a restaurant for the first time, and you need to describe the person to a manager. Typically, the person’s gender would be a part of the description, but what if the person cannot be described as a man or a woman?

Figure: Asia Kate Dillon is a non-binary actor best known for their roles on Orange Is the New Black and Billions. (Credit: Billions Official Youtube Channel / Wikimedia Commons / Attribution 3.0 Unported (CC-BY 3.0))

Within any group, individuals obviously have a right to define themselves; however, collectively, a group’s self-determination is also important. The history of Black Americans demonstrates a progression of self-determined labels: Negro, Afro-American, colored, Black, African American. Similarly, in the nonbinary community, self-described labels have evolved. Nouns such as genderqueer and pronouns such as hir, ze, and Mx. (instead of Miss, Mrs. or Mr.) have entered not only our informal lexicon, but the dictionary as well.

Merriam-Webster’s dictionary includes a definition of “they” that denotes a nonbinary identity, that is, someone who fluidly moves between male and female identities.

Transgender men and women were assigned a gender identity at birth that does not fit their identity. Even though our culture is increasingly giving space to non-heteronormative (straight) people to speak out and live openly, they do so at a risk. Violence against gay, nonbinary, and transgender people occurs at more frequent rates than for other groups.

To make ourselves feel comfortable, we often want people to fall into specific categories so that our own social identity is clear. However, instead of asking someone to make us feel comfortable, we should accept the identity people choose for themselves. Cultural competency includes respectfully addressing individuals as they ask to be addressed.

Table Gender Pronoun Examples

| Subjective | Objective | Possessive | Reflexive | Example |

| She | Her | Hers | Herself | She is speaking.

I listened to her. The backpack is hers. |

| He | Him | His | Himself | He is speaking.

I listened to to him. The backpack is his. |

| They | Them | Theirs | Themself | They are speaking.

I listened to them. The backpack is theirs. |

| Ze | Hir/Zir | Hirs/Zirs | Hirself/Zirself | Ze is speaking.

I listened to hir. The backpack is Zirself. |

Intersectionality

The many layers of our multiple identities do not fit together like puzzle pieces with clear boundaries between one piece and another. Our identities overlap, creating a combined identity in which one aspect is inseparable from the next.

The term intersectionality was coined by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989 to describe how the experience of Black women was a unique combination of gender and race that could not be divided into two separate identities. In other words, this group could not be seen solely as women or solely as Black; where their identities overlapped is considered the “intersection,” or crossroads, where identities combine in specific and inseparable ways.

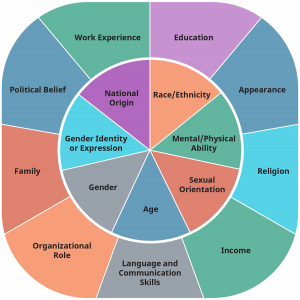

Figure: Our identities are formed by dozens of factors, sometimes represented in intersection wheels. Consider the subset of identity elements represented here. Generally, the outer ring are elements that may change relatively often, while the inner circle are often considered more permanent. (There are certainly exceptions.) How does each contribute to who you are, and how would possible change alter your self-defined identity?

Intersectionality and awareness of intersectionality can drive societal change, both in how people see themselves and how they interact with others. That experience can be very inward-facing or can be more external. It can also lead to debate and challenges. For example, the term “Latinx” is growing in use because it is seen as more inclusive than “Latino/Latina,” but some people—including scholars and advocates—lay out substantive arguments against its use. While the debate continues, it serves as an important reminder of a key element of intersectionality: Never assume that all people in a certain group or population feel the same way. Why not? Because people are more than any one element of their identity; they are defined by more than their race, color, geographic origin, gender, or socio-economic status. The overlapping aspects of each person’s identity and experiences will create a unique perspective.

ANALYSIS QUESTION

Consider the intersectionality of race, gender, and sexuality; religion, ethnicity, and geography; military experience; age and socioeconomic status; and many other ways our identities overlap. Consider how these overlap in you.

Do you know people who talk easily about their various identities? How does it inform the way you interact with them?

Footnotes

- 5APA Dictionary of Psychology https://dictionary.apa.org/identity proper citation to come

Privilege Is Not Just for White People

Privilege is a right or exemption from liability or duty granted as a special benefit or advantage. Oppression is the result of the “use of institutional privilege and power, wherein one person or group benefits at the expense of another,”9 according to the University of Southern California Suzanne Dworak Peck School of Social Work.

Just as everyone has implicit bias, everyone has a certain amount of privilege, too. For example, consider the privilege brought by being a certain height. If someone’s height is close to the average height, they likely have a privilege of convenience when it comes to many day-to-day activities. A person of average height does not need assistance reaching items on high store shelves and does not need adjustments to their car to reach the brake pedal. There is nothing wrong with having this privilege, but recognizing it, especially when considering others who do not share it, can be eye-opening and empowering.

Wealthy people have privilege of not having to struggle economically. The wealthy can build retirement savings, can afford to live in the safest of neighborhoods, and can afford to pay out of pocket for their children’s private education. People with a college education and advanced degrees are privileged because a college degree allows for a better choice of employment and earning potential. Their privilege does not erase the hard work and sacrifice necessary to earn those degrees, but the degrees often lead to advantages. And, yes, White people are privileged over racial minorities. Remember Malcolm Gladwell’s explanation of how he was treated when people assumed he was White as opposed to how people treated him when they assumed he was Black?

It is no one’s fault that they may have privilege in any given situation. In pursuit of civility, diversity, equity, and inclusion, the goal is to not exploit privilege but to share it. What does that mean? It means that when given an opportunity to hire a new employee or even pick someone for your study group, you try to be inclusive and not dismiss someone who has not had the same academic advantages as you. Perhaps you could mentor a student who might otherwise feel isolated. Sharing your privilege could also mean recognizing when diversity is absent, speaking out on issues others feel intimidated about supporting, and making donations to causes you find worthy.

In pursuit of civility, diversity, equity, and inclusion, the goal is to not exploit privilege but to share it.

When you are culturally competent, you become aware of how your privilege may put others at a disadvantage. With some effort, you can level the playing field without making yourself vulnerable to falling behind.

Activity

Think about a regular activity such as going to a class. In what ways are you privileged in that situation? How can you share your privilege with others?

Your Future and Cultural Competency

Where will you be in five years? Will you own your own business? Will you be a stay-at-home parent? Will you be making your way up the corporate ladder of your dream job? Will you be pursuing an advanced degree? Maybe you will have settled into an entry-level job with good benefits and be willing to stay there for a while. Wherever life leads you in the future, you will need to be culturally competent. Your competency will be a valuable skill not only because of the increasing diversity and awareness in America, but also because we live in a world with increasing global connections.

If you do not speak a second language, try to learn one. If you can travel, do so, even if it is to another state or region of the United States. See how others live to understand their experience and yours. To quote Mark Twain, “Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness.” The more we expose ourselves to different cultures and experiences, the more understanding and tolerance we tend to have.

The United States is not perfect in its practice of diversity, equity, and inclusion. Still, compared to much of the world, Americans are privileged on several fronts. Not everyone can pursue their dreams as freely as Americans do. Our democratic elections and representative government give us a role in our future.

Understanding diversity and being culturally competent will make for a better future for everyone.

Footnotes

- 9Golbach, Jeremy. “A Guide to Discussion Identity, Power, and Privilege.” https://msw.usc.edu/mswusc-blog/diversity-workshop-guide-to-discussing-identity-power-and-privilege/

Curator’s note: This chapter was created as a project for an Stanford University EPIC (Education Partnership for Internationalizing Curriculum) Global Studies Fellowship project.

Licenses and Attributions:

The Life in Quarantine Project was designed by Stanford University graduate students Nelson Shuchmacher Endebo, Farah Bazzi, and Ellis Schriefer.

CC licensed content, Original:

- Shanta by Annie Christianx. License: CC BY: Attribution.

- America by Tramaine Wilkes. License: CC BY: Attribution.

CC licensed content, Shared previously:

- Global Pathways: Cultural Competence Curriculum Module. Authored by Monica G. Burke, Ric Keaster, Hideko Norman, and Nielson Pereira. Located at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/csa_fac_pub/71 License: CC BY: Attribution

- Diversity and Cultural Competency. Authored by: Laura Lucas. Provided by: Austin Community College. Located at: https://www.oercommons.org/courseware/module/25874/student/?task=1 License: CC BY: Attribution

- Introduction to Sociology 2e (Chapter 10.1). Authored by: OpenStax CNX, Heather Griffiths, Nathan Keirns, et al. Located at: https://cnx.org/contents/AgQDEnLI@12.5:7TCPamHd@7/10-1-Global-Stratification-and-Classification. The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the creative commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University. For questions regarding this license, please contact support@openstax.org. Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/02040312-72c8-441e-a685-20e9333f3e1d@12.5All rights reserved content:

- Cultural Competency at Rutgers University Behavioral Health Care. Provided by: UBHC Production Studio. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c-h1ZuRXBpg. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube License.

- The DNA Journey. Provided by momondo. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tyaEQEmt5ls. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube License.