82 Central Asia: Economic Geography I – The Aral Sea Debacle

Imagine Lake Michigan being nearly dry and empty. It seems impossible.

Visualize Lake Michigan no longer being connected to Lake Huron in the north. Can you see Green Bay (the bay, not the city) as a small puddle, separate and nearby?

Consider that boats no longer traverse Lake Michigan for trade or transportation, but instead many ships sit rusted and many miles from the former shoreline.

Don’t worry whether or not the Asian carp reaches Lake Michigan, for the little water left in the lake supports very few fish. The shorelines that once held a variety of flora and fauna now are nearly barren without the water’s presence.

Science fiction? A monstrous story? No, this is the account of the decline of the Aral Sea. The problem of the Aral Sea was caused by a grossly mismanaged economic plan that in the end created great economic and ecological damage.

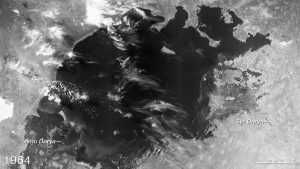

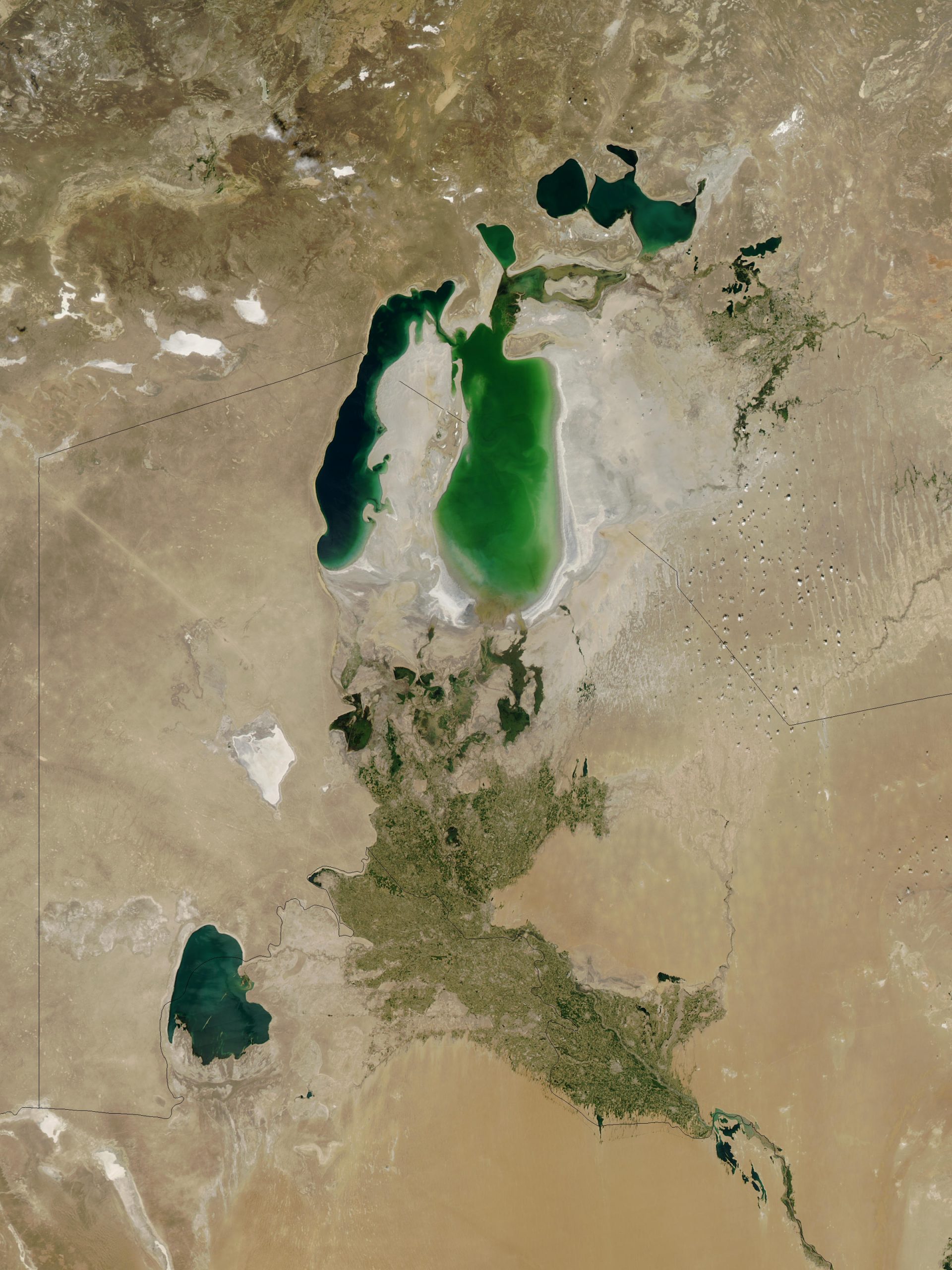

The Aral Sea, located between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, once was the fourth largest lake in the world, thus larger than Lake Michigan. Yes, it too was a lake, for it does not connect to the world’s oceans, that a requirement for being labelled a sea. Due to disastrous misuse begun during Soviet times, the Aral Sea has split into smaller lakes, nearly disappearing entirely.

In the 1960s, both Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan were part of the Soviet Union, as republics in Central Asia. Thus, the Aral Sea was within the Soviet Union. The Aral Sea is considered an endorheic lake, meaning that it has no outlets. Water flows into the Aral Sea, but not out of it. Hmm, shouldn’t this be an advantage for retaining water? Normally yes, but Soviet mismanagement was normal too.

The Aral Sea has no streams leaving it. How does its water balance out? Well, before Soviet mismanagement, the Aral Sea had two major sources of incoming water – two rivers. The Syr Darya to the north flowed largely from snow melt in the Tien Shan Mountains of Kyrgyzstan, spending most of its length crossing Kazakhstan. Similarly, the Amu Darya to the south flowed much from snow melt in the Pamir Mountains along the border of Afghanistan and Tajikistan, then flowing in Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.

The Syr Darya, historically also known as the Jaxartes River, is about 1400 miles long. Its prominent tributary is the Naryn River. The usual flow of the Syr Darya was between 10 and 20 km3 a year. Excepting minor localized withdrawals of water, this volume reached the Aral Sea.

The Amu Darya, historically also known as the Oxus River, is about 1500 miles long. The usual flow of the Amu Darya was between 30 and 60 km3 a year, a bit more varied than the Syr Darya. Excepting minor localized withdrawals of water, this volume reached the Aral Sea.

Therefore, the Aral Sea annually received large volumes of fresh water from these two noteworthy rivers. What else? Rain? Not much, as the Aral Sea is located in continental desert climate. Thus, while the rivers contributed a sizable volume of water, little rain falls into this basin. In a desert climate with hot summers, the Aral Sea did suffer some from evaporation. However, with the influx of river water, the sea (lake!) did not vary too substantially in any measure – surface area, volume, depth. There are historical records suggesting that some years the Aral Sea did cause localized flooding.

So, what happened? During the Soviet Union, the planned communist economy established production goals and quotas for industry and agriculture. Even more, the government determined what products would be built or manufactured and for agriculture what crops would be grown and what animals raised. This included Khrushchev’s Virgin Lands program (see Chapter 84) for wheat and corn. In the 1960s, the government began emphasizing the production of cotton in the non-mountainous sections of Central Asia.

Cotton was a preferred crop, for it was a valuable export that earned hard currency. During communism, the Soviet ruble was considered a soft currency. That meant that it did not have an international value. Hard currencies – like the American dollar, the Euro, the British pound, the Japanese yen – these trade on international currency markets and are accepted around the world, having a “hard” value. The Soviet ruble did not have this value, for non-communist countries and corporations did not want to be paid in rubles. The export of cotton internationally could return hard currency payments which then could be used to fund international purchases.

Cotton would grow well in Central Asia given the hot summers; however, cotton requires lots of water. Therefore, historically cotton was only a modest crop in Central Asia. In fact, for most of Central Asia, agriculture was limited and nomadic herding was common. The Fergana Valley was an exception to this pattern, as it traditionally been quite productive.

Public Domain.

Soviet authorities decided that the need for cotton exports was so significant that they designed and began massive irrigation of normally unused dry land. As the Syr Darya and the Amu Darya flowed westward, huge volumes of water were diverted into large irrigation canals and smaller irrigation channels into the crop fields.

As so often was the case in the Soviet Union, planning and implementing were flawed. Consistently, the volume of water taken from the two rivers was more than the crop fields needed or even could hold. It is difficult to imagine, but true that the overflow created new lakes in the desert. The construction of canals was poorly designed and put in place. Most canals were not lined with concrete, but simply dug through the desert soils. Note that water moving over these dry canal floors and walls was naturally absorbed. Thus, some water intended for the cotton fields never reached the crops. Ideally, the canals would have been covered, but this too was not done. As a result, in the hot summers evaporation took place from the surface of the canal waters. More water was lost before reaching the fields.

Photo by Anton Ruiter on Flickr.

Therefore, from the 1960s on, the naturally large flows of water from Central Asia’s largest rivers diminished before they reached the Aral Sea. In some years, literally a trickle dotted the landscape. Nature’s balance for the Aral Sea skewed significantly to dry. As little water arrived, evaporation continued at its normal pace. The waters receded in surface area, dropped in depth, and shrank in volume. Unlike Lake Michigan, the Aral Sea naturally is a saline lake. As water, but of course not salt, evaporated, the salinity of the water rose. Eventually, the plentiful stocks of fish in the Aral Sea declined as the fish could not adapt to the saltier waters. In 1957, the fish catch in the Aral Sea yielded 48000 tons, but eventually the yearly catch would be zero. As the waters receded, the original shorelines no longer met the water, eventually ending up miles away from the water. Transportation, industry, and tourism dried up too.

Of course, the Soviet Union did break up and Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan became independent countries. The Soviet mandate to grow cotton ceased as well. However, the export income earned by cotton sales did not disappear, so Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan continued to irrigate and grow cotton. By this time the ecological disaster of the Aral Sea was well established; nevertheless, massive irrigation of the desert continued in order to maintain cotton yields.

So, what became of the Aral Sea? Can it be fixed? Read the next chapter.

Did you know?

In Turkic languages, aral means island. Thus, the Aral Sea refers to a sea of islands. Additionally, darya can refer to lake or sea or river in Persian, thus the Amu Darya is the Amu River.

In parts of Tajikistan along the Syr Darya, women are culturally forbidden from wearing bathing suits. Of course, they do not swim nude, but rather do not learn how to swim at all.

Like the Aral Sea, the Caspian Sea is a lake.

My Turn!

CITED AND ADDITIONAL BIBLIOGRAPHY:

The Annual Flow of Source Rivers (the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya) into the Aral Sea. ResearchGate, Oct. 2020, https://www.researchgate.net/figure/The-annual-flow-of-source-rivers-the-Amu-Darya-and-the-Syr-Darya-into-the-Aral-Sea_fig5_344460701.

“Aral Sea: Big Fish Is Back in Small Pond.” Reuters, 1 June 2017. www.reuters.com, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-kazakhstan-aral-idUSKBN18S4ZV.

The Aral Sea Crisis. http://www.columbia.edu/~tmt2120/introduction.htm.

“The Aral Sea: The Difficult Return of Water.” We Are Water, https://www.wearewater.org/en/the-aral-sea-the-difficult-return-of-water_322871.

carylsue. “Once Written Off for Dead, the Aral Sea Is Now Full of Life.” National Geographic Education Blog, 21 Mar. 2018, https://blog.education.nationalgeographic.org/2018/03/21/once-written-off-for-dead-the-aral-sea-is-now-full-of-life/.

Pannier, Bruce. “The Demands On Central Asia’s Great Naryn And Syr Darya Rivers.” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 7 Aug. 2021. www.rferl.org, https://www.rferl.org/a/naryn-syr-darya-rivers/31398202.html.

Ruiter, Anton. Aral Sea, Moynaq, Uzbekistan. Photo, 30 Aug. 2011. Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/antonruiter/6317970431/. Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.0).