47 SE Asia: Economic Geography II – Landlocked Laos

Being a landlocked country is a major disadvantage in a globalized word. The definition of a landlocked country is straightforward. Being landlocked means that a country lacks any borders on bodies of water that are oceans or that connect to an ocean. Of course, in every region of the world, there are a multitude of countries that have ocean coastlines. Additionally, there are many countries that face a sea that directly connects to an ocean. Obviously, Italy is not landlocked for it has lengthy coastlines on the Mediterranean Sea that connects via the Strait of Gibraltar to the Atlantic Ocean. In the Eastern World, the same is true for Iran, which borders the Persian Gulf that connects through the Strait of Hormuz to the Indian Ocean.

In contrast, while Azerbaijan borders the Caspian Sea, this sea does not connect to the ocean; therefore, Azerbaijan is considered landlocked. This is not intuitive when a glance at the map shows over 400 miles of coastline on the Caspian Sea. Azerbaijan may benefit from certain aspects of the Caspian Sea – fishing, scenic coastline; however, it does not have the crucial economic benefit of straightforward international worldwide shipping.

About 80% of international trade is done by shipping on the open seas. In order to participate in international shipping, a landlocked country must gain the cooperation of adjacent coastal countries. This requires additional forms of transportation, break-of-bulk locations (where product is off-loaded and on-loaded to separate transport modes), border crossings, port access, and so on.

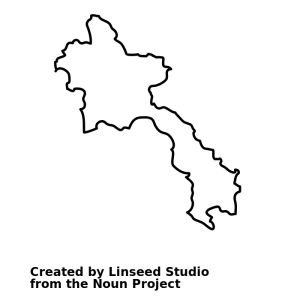

For Southeast Asia, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Laos) is the only country that meets this definition of a landlocked country. In fact, recall Chapter 38 on Southeast Asia, where we noted the importance and commonality of coastline for the islands of the region. The same is true for continental SE Asia, where most countries have elongated shapes that seek to maximize ocean coastline. To the credit of Laos, while it is landlocked, the country is neither the poorest nor least developed country in the region. Certainly, some of this credit goes to focusing on a policy of “land-linked.”

In Southeast Asia, tiny East Timor (142nd), Cambodia (144th), and Myanmar (147th) are ranked lower than Laos (137th) in the Human Development Index. The results are similar when assessed by GDP per capita – East Timor (121st), Laos (123rd), Myanmar (129th), Cambodia (143rd). Even so, given Laos’ landlocked situation, one would expect that Laos would rank last among Southeast Asian countries in multiple economic categories.

Let’s consider how Laos has worked to overcome its landlocked disadvantage.

1 – One of the ways that Laos works its way economically higher is by participating in the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS). Laos prioritized trade with its highly populated neighbors. Over 80% of both imports and exports for Laos are contributed by three neighboring countries – China – 1.4 billion people, with the Yunnan Province bordering Laos, Vietnam – may hit 100 million in 2022, and Thailand – 70 million. (Of course, Indonesia is the 4th most populated country in the world, but in SE Asia is far from Laos.) Within the Greater Mekong Subregion, Laos features road networks including sections of the Great Asian Highway. The GMS East-West Corridor intersects southern Laos to connect to the major port city of Danang, Vietnam.

Trade with China will be enhanced through the construction of the Vientiane-Boten highway. This highway will extend from the national capital city Vientiane to the Chinese border city Mohan across from the Laotian city Boten. Construction is proceeding in segments. The Vientiane to Vang Vieng section of the highway was completed in 2020, having been funded (95%) by Chinese developer Yunnan Construction Engineering Group. This highway will be a much faster parallel road to Route 13 which has long been the most important road in Laos. Route 13, however, often is in disrepair, so that the new highway will be a great improvement in quality and speed of travel. Other road systems connect to Hanoi, Vietnam, and to Bangkok, Thailand. For a map highlighting economic corridors for SE Asia, go to:

https://greatermekong.org/content/economic-corridors-in-the-greater-mekong-subregion

Land-linked, indeed.

2 – Regional trade agreements. Via the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in part. Laos can expand trade into major markets, even into huge markets outside SE Asia – China and India, for instance. In 1997, Laos joined ASEAN which seeks to “accelerate the economic growth, social progress and cultural development in the region through joint endeavours in the spirit of equality and partnership … .”1 While not solely an economic organization, ASEAN promotes cooperation among countries, mainly in this region. A specifically economic aspect of ASEAN is concordant membership in the ASEAN Free Trade Association (AFTA). In 2009, AFTA extended its reach with a free trade pact with Australia and New Zealand.

3 – Seeking diversification of products. In the last decade, Laos’ rank in the Economic Complexity Index has risen slightly, from 120th to 116th. About 63% of Laotian exports are resource-based. Its number one export (20%) is electricity, as generated from hydropower on the Mekong River. Laos is pushing to gain a greater share of manufacturing. For 2011-2021, the Laotian economy grew at a compound annual growth grade (CAGR) of 6.7%. This number ranked sixth highest in the world.

Overall, Laos remains a developing economy, but with legitimate optimism for the future. With heavily populated neighbors connected by road corridors, Laos has a strong economic floor tied to a land-linked focus. The height of its economic ceiling is not known yet, but should benefit from increasing economic diversification within the country and from expanding international trade with neighboring ports and via trade agreements.

Did you know?

An endorheic lake is a basin that does not have outflow to other bodies of water. These types of lakes are most common in Central Asia. A landlocked country may feature an endorheic lake.

My Turn!

CITED AND ADDITIONAL BIBLIOGRAPHY:

“Economic Corridors in the Greater Mekong Subregion.” Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS), 25 Aug. 2017, https://greatermekong.org/content/economic-corridors-in-the-greater-mekong-subregion.

GDP per Capita – Worldometer. 2017. https://www.worldometers.info/gdp/gdp-per-capita/.

Kunze, Gretchen A., et al. “In Laos: Land-Linked, Not Land-Locked.” The Asia Foundation, 27 Aug. 2008, https://asiafoundation.org/2008/08/27/in-laos-land-linked-not-land-locked/.

“Laos (LAO) Exports, Imports, and Trade Partners | OEC.” OEC – The Observatory of Economic Complexity, https://oec.world/en/profile/country/lao.

“Laos by Linseed Studio from NounProject.com.” https://thenounproject.com/icon/laos-724434/.

“List of Countries by Human Development Index.” Wikipedia, 13 Mar. 2022. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=List_of_countries_by_Human_Development_Index&oldid=1076914058.

Popovic, Sasha. Laos. January 7, 2017. Photo. https://www.flickr.com/photos/68637044@N05/31886363060/. Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Seno-Alday, Sandra. “How Laos Is Overcoming Landlockedness and Bolstering Growth.” East Asia Forum, 5 Mar. 2021, https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2021/03/05/how-laos-is-overcoming-landlockedness-and-bolstering-growth/.

UNIDO Statistics Data Portal. https://stat.unido.org/content/publications/competitive-industrial-performance-index-2020%253a-country-profiles?_ga=2.86059096.1187667958.1647554532-1672593690.1647554532.

Wiertz, Steve. Laos. College of DuPage GIS class.