8 “Words Do Things in the World”

Stacey Van Dahm

Stacy Van Dahm overviews the importance of everyday writing and reading by reminding the reader that the more you practice and engage, the more you are able to engage with a larger variety of texts, as well as audiences. Dahm explains how texts are set in place to empower and illustrates how behind each piece, there is an argument to unpack or an active writing or strategy in place to analyze.

WRITING IS AN EVERYDAY ACTION

We take literacy for granted sometimes. We all write, all the time, but often people don’t think of themselves as writers. We might even falter sometimes in explaining the obvious ― that writing and reading empower us to do things, to change our lives, to change the world. Or simply to get a cup of coffee with a friend.

I think we’re less conscious of writing because writing is a tool that we use every day, like a fork or a toothbrush. Or a keyboard. Writing is sometimes mundane. You might leave a note for your parent or roommate saying when you’ll be home. You might send a quick email to a relative or instructor or someone at work. You might post a comment on social media, text a friend about going out, fill out an application, or draft an essay for a class. You actually write all the time. It’s true. You take advantage of your literacy ― writing and reading ― every day. It’s like a superpower we forget we have. But texting your friend about a cup of coffee (or to study, or whatever) can lead to sharing some important time with someone you care about. A little text message can lead to human connection ― the most important thing.

I’m a big fan of dystopian literature and film. One common trope or structuring theme we find in dystopian fiction is illiteracy or, really, control over who gets to learn to read and write and what information is available to people. In Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) the “World Controllers” create and disseminate the official history of the World State, and they intentionally remove strong human emotion ― by giving everyone the drug, Soma ― in order to sustain a peaceful society. The state enforces peace by eliminating access to literature, art, science, and religion.

Imagine a world in which you weren’t allowed to read your favorite novel …

Or a world in which government-mandated medication dulled the senses.

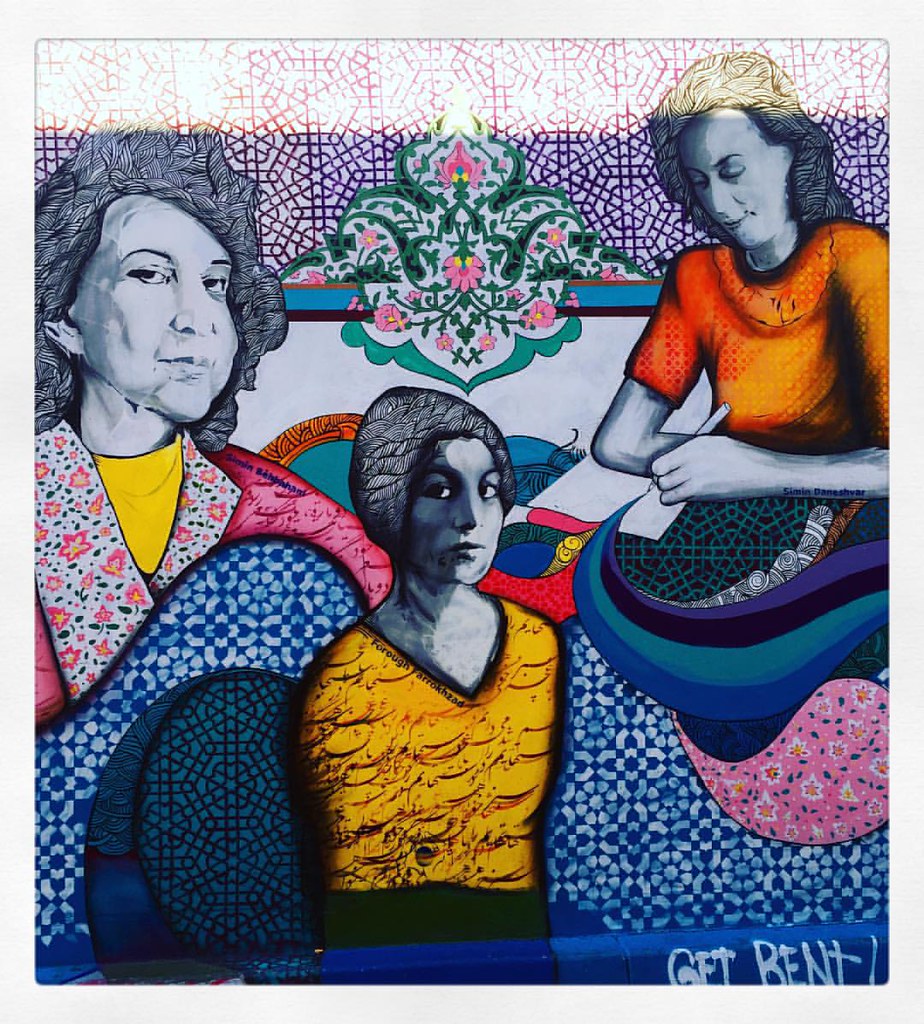

In Margaret Atwood’s famous novel, The Handmaid’s Tale (1985), which is now a popular TV show, we can see how within the space of just one or two generations, the new society of Gilead will be filled with young people who do not know about the past at all. This is because girls are completely forbidden from reading and writing and boys are taught a tailored version of history and religion. The entire economic and political system resides on highly restricted, gender-based roles for everyone. You have probably seen the red uniform of the handmaid as a popular form of social critique in our society today. As people learn only their assigned position in society, they lose unique ways to express themselves.

Both books demonstrate how controlling what people say and what information they have access to means controlling people. Illiteracy means the erasure of history, a dumbing down of society, implosion. People who control the words control most other things.

So, if literacy is so important, then why do we sometimes take it for granted in our everyday lives? It’s probably because small, everyday rhetorical gestures (from text messages to a note on the fridge to an email at work) don’t usually change the world. We don’t always recognize that these are part of the way we move through life. But all of our writing counts. The introduction to Towards a Rhetoric of Everyday Life (2003) defines rhetoric as “the ways that individuals and groups use language to constitute their social realities, and as a medium for creating, managing, or resisting ideological meanings” (Nystrand and Duffy ix). The words we use every day help us to navigate our social realities, to situate ourselves in our communities and societies. They demonstrate who we are in relation to ideas and other people.

For some humorous examples of notes that can make a difference, you might check these out.

Literacy is empowering. It is how people escape oppression, change their circumstances, think critically about what’s going on, and argue for change. In fact, in the novels mentioned above, literacy helps to break down the oppressive system because inquisitive and determined characters access forbidden information, use their literacy skills or learn some, and ask critical questions of the systems that oppress them.

Consider the ways you have used reading and writing in the past year to navigate your social reality. If you signed a petition, emailed your representative, cast a ballot, posted something important to you on social media, applied for college, wrote an essay, or wrote a note to a loved one, you engaged your rhetorical skills in a way that helped situate you in relation to the things you care about. You empowered yourself using literacy.

SMALL RHETORICAL GESTURES CAN BE PART OF SIGNIFICANT CHANGE

When we put our words into the world, we usually expect an outcome. In any writing you’ve done recently, you might have achieved your aims, or it might be too early to tell, but if you found yourself hoping for a response, that’s a reminder that writing is much more than just a tool, because language has power. Even the smallest rhetorical gestures can be part of significant change because our words have consequences. When your parents know when you’ll be home, they might make sure to have dinner ready for you. When your instructor understands your situation, they might give you an extension for your project. And when you make a strong case for a promotion at work, you might get a raise. Writing is the engine of our lives because people act on our words. When we put our words into the world, they do things.

If we thought about that more often, we would probably reflect on the power of our own literacy a little bit more. Words are like people; when you get a bunch of them together, interacting, they can do huge things, powerful, world-changing, mind-bending things. And words, like people, can collide and create reactions that are bigger than the sum of their parts. Of course, words don’t happen separately from people. Consider mass protests in which words bring people together to make a political or social statement further articulated in signs, chants, and slogans.

We can even say that putting our words into the world is an action in itself. Speech Act Theory, developed by British philosopher and linguist J. L. Austin and philosopher J.R. Searle, in the 1960s and ’70s, became a basis for analyzing language this way. The title of Austin’s collected lectures was How to Do Things with Words (1962), which gives a pretty good idea of his views on language. Austin and Searle studied the difference between utterances that describe something ― “someday I’m going to get married” ― and words that act ― as when one answers “I will” in response to a marriage proposal or “I do” at a wedding ceremony. “I do” ― just two small words ― can have a huge impact on the lives of those involved, for generations. The words we speak and write have consequences, a ripple effect that keeps going, like the multiple generations of a family.

Social media is a space in which our own words contribute to a sense of our identities and influence the way others see us and what communities we stand with. When we post a response to a social or political issue or even share a news item, we are by proxy articulating our own values and views. In fact, social media has become important for political organizing and social activism. This “Clictivism” has been criticized as a rather passive and sometimes harmful way for people to try to create change, but it has also contributed to powerful and important change in the world (Butler). The truth is, if you’ve participated in a social action of any kind in the last couple years, it’s very likely you were connected to it via social media. Consider the breadth of the Black Lives Matter protests across the nation and the world in 2020. Social media helped facilitate this mass action, and the tenets of the movement have had a huge impact ― consequences ― in policing, racial accountability, and institutional commitments toward inclusivity and equity across the country.

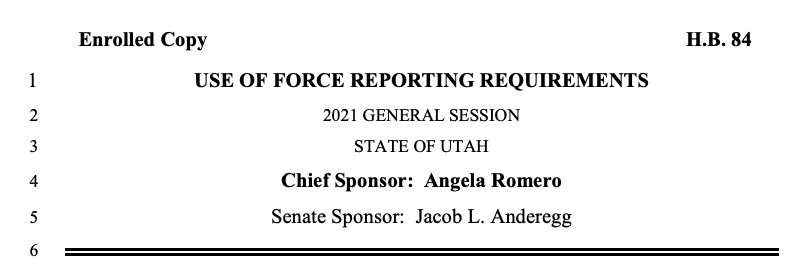

Two 2021 bills in Utah demonstrate how ideas move to action with real consequences in the world.

An important event that exemplifies how words have consequences is the tension around the 2020 presidential election and the infiltration of the capital on January 6, 2021. After having claimed for weeks that the election was stolen ― though without evidence ― former president Donald Trump was accused of inciting an insurrection at the capitol on January 6, the day that congress was supposed to certify the election results marking Joe Biden as the winner. In his speech that day, the former president made several statements that have been linked to the violence at the capital, including: “We fight like hell. And if you don’t fight like hell, you’re not going to have a country anymore” (Naylor). While some suggest this phrase incited protesters to violently overrun the capital, others argue that the words were meant figuratively. In fact, this is a false binary. Words have meaning and act on listeners beyond the intent or expectations of the speaker. Some may dismiss these words, others may protest, some may sign petitions, others may argue with their relatives on social media. But there are some who will take violent action.

So, words can lead to action that goes beyond our expectations. And that leads to the final point here.

THERE IS ALWAYS AN ETHICAL COMPONENT TO WRITING

Our words have consequences in our lives and in the lives of those around us. This means there is always an ethical component to writing. From the name of the January 6 march, “Save America,” to the numerous signs and banners, to the various ways the event was covered by the media ― multiple messages contributed to strong ideological views about the election, and the meanings of “America” and “freedom.” In the midst of this fervor, hundreds of protestors stormed the capital, transforming the event into an insurrection that involved $30 million in damages, violence, and death. NPR, reflecting on its own coverage of these events, demonstrated how powerful media representation is when it published an analysis, on January 14, 2021, of the way its own discourse covering the event evolved over the course of several days. They chose to call those involved “pro-Trump extremists” not “domestic terrorists.” The word “protestors” changed later to “mob” and “rioters.” All of these word choices impact the way listeners think about the events of January 6. You might also note my own word choices above: “infiltration,” “insurrection,” “violence,” and “overrun,” for example. I chose these carefully. A look through Fox News headlines shows terms like “riot,” “stormed,” “seizure.” The words we use reflect and influence thinking, choices, and action. Where we might not often see such extreme action taken in response to political speech, we can recognize that it impacts our own choices quite often ― from how we vote on policies and candidates, to what media we consume, to where we live, and even what communities we choose to join and which ones we avoid ― or outright reject.

Sometimes dystopian fiction helps us imagine what life would be like without the kinds of political discourse and emotional speech that incites such strong reactions. The 2014 film The Giver, based on Lois Lowry’s 1993 novel of the same name, limits speech and historical memory by putting it in the hands ― the heart and mind ― of just one member in the community, the main character, Jonas. When he reaches adulthood, Jonas is chosen to be the Receiver of Memory for all the community. Beyond suppression of memory, people in this society are controlled by other common dystopian tropes: suppression of emotion (through medication), strict rules enforcing equality (in this case sameness), and deconstruction of familial affiliation (infants are raised in a nurturing center). The film version uses color, or lack thereof, as a way to emphasize the blandness of such a controlled life. When Jonas rebels and passes beyond the boundary of his community, this “releases” the memories so that everyone experiences them and learns about the past; they suddenly feel true emotion. The film conveys this by washing the usually black and white scenery with vivid colors.

As lush images and sounds of diverse human experiences of joy and pain, love and loss, war and celebration fill the scene and flood people’s consciousness, The Giver asks us to consider the true definition of freedom and the cost of peace. In this case, freedom was suppressed by limiting access to historical knowledge for the sake of a bland peacefulness in society, a harmony devoid of human feeling. Literacy is suppressed to stop people from feeling, from desiring something different, or understanding the ways their own society oppresses them. In this way, these texts argue that words and images that share the stories of human experience have immeasurable power in the world.

The ethical implications of inciting violence, rejecting those who hold a different worldview, or withholding human emotion and history are incredibly important. These acts work against human connection. In all these cases, we can see that the words people use and withholding or altering information all have consequences that go far beyond any expectation. In the study of rhetoric, there is a long history of linking rhetoric to ethics. One well-known voice in this discussion is John Duffy. This scholar suggests that writing is a practice of virtue. Teaching writing, he argues, means to teach the “communicative practices of honesty, accountability, compassion, [and] intellectual courage” (213). Writing and honesty go hand in hand. In my classes you’ll hear me say that “effective rhetoric is ethical rhetoric.” I mean that the most effective means of persuasion include careful and transparent reasoning, credible and substantiated evidence, and awareness of the human experiences we impact with our writing.

It might be easy for an ad to persuade us by massaging the facts, but that leads to short-term results, shallow responses, even unethical choices. None of us want to be persuaded by lies or trickery. This becomes more salient when we recognize that our words have consequences. We might not always know what effect they will have, but we are responsible for trying to understand just that.

One final example is helpful here: the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, during the Cold War. This was before I was born and probably before you were born, but it’s pretty important because we likely wouldn’t have been born at all had things not worked out. In brief, the Soviet Union started to build medium-range nuclear missiles in Communist Cuba. The U.S. wasn’t having it. So, the two leaders, John F. Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev, had some words. Letters, to be more precise, archived in the JFK Library online as “The World on the Brink.” Consider the rhetorical situation (the context and purpose). Each leader had an entire nation to appease, Kennedy during an election year, Khrushchev recognizing a nuclear arms gap that favored the U.S. The eyes of the world were on them because one false step would lead to nuclear disaster ― apocalyptic, dystopian-level annihilation. Neither could afford to simply back down. It was in the interest of all of humanity for them to find a peaceful and face-saving solution to this crisis. Here are a few excerpts to demonstrate the nature of this conversation:

Kennedy to Khrushchev, 22 October 1962

… I expressed our readiness and desire to find, through peaceful negotiation, a solution to any and all problems that divide us.

Khrushchev to Kennedy, 23 October 1962

We affirm that the armaments which are in Cuba, regardless of the classification to which they may belong, are intended solely for defensive purposes …

Kennedy to Khrushchev, 25 October 1962

I urged restraint upon those in this country who were urging action …

Khrushchev to Kennedy, 26 October 1962

I think you will understand me correctly if you are really concerned about the welfare of the world.

War is our enemy and a calamity for all the peoples.

I see, Mr. President, that you too are not devoid of a sense of anxiety for the fate of the world …

You are mistaken if you think that any of our means on Cuba are offensive.

There, Mr. President, are my thoughts, which, if you agreed with them, could put an end to that tense situation which is disturbing all peoples.

These thoughts are dictated by a sincere desire to relieve the situation, to remove the threat of war.

Khrushchev to Kennedy, 28 October 1962

It took them about a month of exchanging letters to get there. But they got there. Not with aggressive action, but with words. Of course, this event was much more complicated than I’ve represented here, but the point is there is no doubt that each leader understood well the ethical implications of each word, each sentence of their exchange.

CONCLUSION

Literacy is a sometimes underappreciated superpower. When we write, our words take flight and do things in the world. When your words connect you with a friend or ensure your place at the dinner table, they are important. And they are important when they win you admission to college or express the beautiful fragility of human experience in a story or poem. Your words have consequences. They open a space for you in communities, and they allow you to share your perspective and convince others that it’s a sensible one. And words always have ethical implications. We should use them often, effusively, creatively, and with care.

Works Cited

Austin, J. L. How to Do Things with Words. Harvard UP, 2nd edition, 1975.

Butler, Mary. Clicktivism, Slacktivism, or ‘Real’ Activism: Cultural Codes of American Activism in the Internet Era. MA Thesis, University of Colorado, 2011. scholar.colorado.edu.

Duffy, John. “Ethical Dispositions: A Discourse for Rhetoric and Composition.” JAC, vol. 34, no. 1/2, 2014, pp. 209–237. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/44781859. Accessed 19 May 2021.

The Giver. Directed by Phillip Noyce, performances by Brenton Thwaites, Odeya Rush, Jeff Bridges, and Meryl Streep, The Weinstein Company, 2014.

Huxley, Aldous. Brave New World. Harper, 2010.

Lowry, Lisa. The Giver. HMH Books for Young Readers. 1993

Naylor, Brian. “Read Trump’s Jan. 6 Speech, a Key Part of Impeachment Trial.” NPR, 10 February 2021. www.npr.org/2021/02/10/966396848/read-trumps-jan-6-speech-a-key-part-of-impeachment-trial. Accessed 19 May 2021.

Nystrand, Martin and John Duffy. “Introduction.” Towards a Rhetoric of Everyday Life: New Directions in Research on Writing, Text, and Discourse. Eds. P. Martin Nystrand and John Duffy. University of Wisconsin Press, 2003.

Searle, J. R. Speech Acts: An Essay in the Philosophy of Language. Cambridge UP, 1969.

“The World on the Brink: Thirteen Days in October 1962.” John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. microsites.jfklibrary.org/cmc/ Accessed 19 May 2021.