11 Working with Sources: Worknets and Invention

Kate Pantelides; Jennifer Clary-Lemon; and Derek Mueller

This article illustrates how to successfully incorporate a wide array of sources into your work by first analyzing how the piece came to be and then analyzing how it works alongside your work. Additionally, it discusses the importance of establishing credibility in both sources and your writing, the importance of recognizing how scholars communicate with one another, and how it ultimately positions you to further understand your research.

To work with materials successfully, practitioners in many fields study how something is made. They may turn to instructions and diagrams, or they may take apart and put back together equipment. They may follow steps essential to understanding better how things fit together, which parts of a system are dependent on which other parts, and how—when things go well—the system operates.

For example, a materials engineer at a bicycle manufacturer may look at other models or even collect samples of bicycles and take them for a ride. The materials engineer might ponder, alone or in consultation with others, alternatives for any individual part or material necessary to the bike’s functioning. She might take notes, draw and scribble about connections, or make mock-up prototypes.

In another comparable scenario, a pizza maker might follow a dough recipe several times before making a change to an essential component, such as trying a new oil or yeast or flour, or perhaps modifying resting time or the kneading process. The ingredients and process are both built up intricately and periodically unbuilt to ensure great familiarity with how things work.

Writing researchers frequently read, study, and consult sources as a way to stay apprised of new knowledge as well as long-established histories relevant to their questions. Sources are tremendously important among the materials writing researchers work with.

The reason researchers cite sources is simple: to establish credibility—build their ethos—writers have to show that they are members of their academic communities. They do this by pointing to other writers who have had, and are having, the research conversation they are interested in joining. You’ll notice as you read any academic article that it usually begins with a literature review, or a synthesis of sources that shows explicitly that the writer knows the main arguments, or critical conversation, circulating about a particular topic and is then able to carve out a space for their own research question. But what can citing sources do for you? Here are some possibilities:

- It recognizes the history of how sources build on each other by relating new research to past research (homage; timeliness of current research).

- It lends credibility to the author—you!—who, by referencing sources, demonstrates care, ethics, rigor, and knowledge (authority; credibility).

- It revisits claims, data, and key concepts that serve as a foundation to the new research (build-up).

- It positions new research in relationship to the research gaps that it highlights (differentiation).

It’s not enough, in working with a topic—say, climate change—to simply know it is of interest to a variety of scholars. A writer needs to become familiar with the key terms used by the scholarly community working on climate research, such as greenhouse gas and carbon threshold, and the historic data that is fundamental to that research. This might be represented by, for example, how the measurements of carbon levels in the atmosphere that have been taken by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration at the Moana Loa Observatory since 1958 led to noticing that we have surpassed the 400 PPM, or parts per million, carbon threshold that is key to human thinking about climate change. Learning these things allows you to write your way into a complex topic and shows that you know enough to join the conversation.

But how do you begin? This chapter helps you begin to invent ideas by engaging deeply with sources. Seeking and finding appropriate sources and knowing them well enough to incorporate them into your writing is slow work. It can be especially slowed down when you are at the beginning, finding your way into an unfamiliar conversation for the first time. It takes time to trace even a sample of the relations that reach through and across sources.

In this chapter, we focus on one way that you can work with a text, or source, through working with the webs of relationships that extend out from it, or its web of connections with other sources. We call this kind of working with multiple texts sourcework, and it can show itself in a variety of ways—often through library research, keyword searches, paging through a source’s bibliography or Works Cited page, or following a trail of online links or even a hunch about a key idea. Yet sourcework takes time, and that’s something many student writers don’t have a lot of when they are trying to navigate a complex topic and key details of a nuanced argument—all from one source! Given the time it takes to work with sources effectively, here we introduce you to a method of sourcework that we call worknets, a four-part model of working your way through one source such that it leads you towards other sources and ideas that will be useful to the thinking and framing of your project.

The Power of Worknets

Worknets give us a visual model for understanding how sources interrelate, how key words and ideas become attached to certain people, and why provenance—when something was written and where it came from—matters. At the center of any worknet is the source that you or your instructor sees as focal to the conversations happening in your research. Radiating outward from that source, as spokes from a wheel, are what we call nodal connections. Each nodal connection gives you another research path to follow and another way to connect with your source more deeply and less superficially. Often students are called upon to “incorporate five or seven or x sources” as though this is a quick and easy task—it isn’t! But when you can treat a central source as one that leads you in a series of directions, each with its own path toward another source, concept, person, or event, you are more likely to read the whole thing. This will help you understand sources more fully, investigate what you don’t understand, and more easily locate another source. It will also help you gather sources together and see how they connect to each other and what gaps in the sources emerge, which helps you piece together a literature review with your research question front and center.

Worknets provide you with a method for working within and across academic sources. As a way of helping you “invent” what you have to say, worknets are a source-based way of helping you to generate a path for your research that points you toward a particular question, gap, or needed extension of what has come before. A finished worknet consists of four phases: a semantic phase, which looks at significant words and phrases repeated in the text; a bibliographic phase, which connects your central or focal source to the other works the author has cited in her piece; an affinity phase, which shows how personal relationships shape sourcework; and a choric phase, which allows researchers to freely associate historic and sociocultural connections to the central source text.* After developing a finished worknet, which involves all four phases placed visually together, you will have many openings for further research, and you will have gained a handle on the central source such that incorporating it into your writing via direct quotation, paraphrase, or summary is easier for you to achieve and more interesting for an audience to read. Worknets can follow the proposal you developed in Chapter 1, or they can offer you a method for reading sources that supports your drafting and refining a research focus and related proposal.

Try This: Summarizing a Central Source (1 hour)

Return to the research proposal that you generated in Chapter 1 or “Making an Argument for Your Research” in Chapter 2. Spend some time coming up with key terms or phrases that succinctly capture your research interests, practicing with Boolean operators such as and, or, and not (e.g., “trees and diseases and campus”; “texting or IM and depression”; “composition and grades not music”). Begin with your library’s databases in your major and, using these key terms, start narrowing your search to academic articles (rather than reviews, newspaper articles, or web pages, for example) using these key terms. Skim at least five sources as you look for your central source, taking notes on the following:

- What is the purpose of the research article?

- What methods did the researchers use to answer their research question?

- What did the researchers find out?

- What is the significance of the research?

- What research still needs to be done?

Taking these notes will allow you to see if the source you’ve read really connects with your curiosities and research direction. They also clearly lay out the basis of most academic articles: a hypothesis (the research question), methods (the tools used to answer a research question), results (what you found out), and discussion (why it matters). Putting these together in 50-100 words allows you to generate a summary of the key points of an academic article, letting you select the article that is the most interesting and central to your research question to begin your worknets.

To develop a worknet, begin by selecting a researched academic article published since 1980.* This date may seem arbitrary, but we consider it a turning point because major citation systems shifted in the 1980s from numbered annotations to alphabetically ordered lists of references or works cited. As you read the article you select, you will, in four distinct but complementary ways, focus on a different dimension of the source’s web of meaning, one at a time. Worknets typically pair a visual model and a written account that discusses the elements featured in the visual model. For the guiding examples that follow, we have developed visual diagrams using Dana Driscoll’s “Introduction to Primary Research: Observations, Surveys, and Interviews,” published in 2011. Driscoll explains in her article the differences between primary and secondary research, details types of qualitative research methods, and provides student examples of research projects to help readers conceptualize her advice about conducting primary research. Because her article ties so closely to what this book is about—research methods—we’ve selected it as a central source to model the worknets process.

Phase 1: Semantic Worknet—What Do Words Mean?

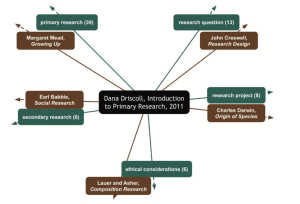

When creating a semantic worknet (Figure 3.1), you pay attention to words and phrases that are repeated throughout the central source (“semantics” is the study of meaning in words). Because academic writers repeat and return to concepts that they want readers to remember, by repetition we begin to understand the idea of a keyword or keyphrase*—those words and phrases that are doing the work of advancing a source’s central ideas. By noticing these key words and phrases, we understand first where they come from and how they have been initiated and second how they are being used to create a common understanding between members of a particular academic discipline, community, or group of specialists. Although such keywords and phrases can at first seem inaccessible, strange, or confusing, noticing them and investigating their meaning is a sure way to begin grasping what the article is about, what knowledge it advances, and the audiences and purposes it aspires to reach.

There are several different ways to come up with a list of keywords and phrases. One approach is to manually circle or underline words and phrases as you read, noting them as they appear and reappear in the text so you can return to them later. Other approaches make use of free online tools, such as TagCrowd (tagcrowd.com/), where you can copy and paste the text of the article and initiate a computer-assisted process that will yield a concordance, or a list of words and the number of times they appear in the text. NGram Analyzer (guidetodatamining.com/ngramAnalyzer/) is another effective tool for processing a text into a list of its one-, two-, and three-word phrases. Across multiple sources, beginning to find words and phrases that match up will help you locate key concepts for the literature review section of your research project.

A semantic worknet also helps you understand specialized vocabulary on your own terms, acting as a gateway into the terminology in the article. Noticing these words and phrases is a first step toward learning what the words and phrases mean. In Figure 3.1, you will see arrows extending outward from each term, radiating toward the edge of the image. This minor detail is a crucial feature of the worknet. It says that there is more, a deeper expanse beyond this article. That is, it suggests the generative reach of the words and phrases stemming from the article. Clearly an echo of the title, the phrase “primary research” appears in Driscoll’s article 39 times, three times more than the next phrase, “research question,” at 13. The article differentiates primary and secondary research. These keywords and phrases remind us of this. But the article also repeats the phrase “research project” and “ethical considerations.” Each of these repeated keywords and phrases are included in the worknet.

Try This: Finding Keywords (30 minutes)

You’ve chosen an article you consider to be interesting and relevant to your emerging research question. In anticipation of developing the semantic phase, spend time analyzing the article by doing the following:

- Read through the article, noting the title and any headings. Make a list of words that you find central to the text.

- Does the article provide a list of keywords at the beginning? If so, do any of them surprise you or differ from what you would have selected? Which ones overlap with the ones you compiled during your reading?

- Choose some of the keywords you’ve identified from the list supplied by the article or from the list you have generated. Next, without looking up any of the terms in the article or in any dictionary, attempt to write brief definitions of these terms. What does each keyword mean? Note with a star those terms you believe to be highly specialized.

After creating your worknet, we encourage you to create a 300-500 word written accompaniment of the visual worknet, based on the questions in the next “Try This,” that helps you think through the “why” of the source’s keywords and phrases. The notes you take as a part of the semantic worknet will not only give you a greater understanding of the central source you’ve read, but will also link to others in the conversation, giving you a fuller body of sources from which to orient your research proposal or project.

In addition to providing insight into the article, the family of ideas it advances, and the disciplinary orientation of the inquiry, noticing keywords and phrases can also inform further research, providing search terms relevant for exploring and locating related sources. It can lead you toward examining why an article covers some things with more repetition (in Driscoll’s example, ethics), but not others (for example, finances and how they relate to ethical choices). When gaps appear between what a source says and does not say, those gaps are interesting places to orient your own research question.

Try This: Developing your Semantic Worknet (1-2 hours)

Select three to five keywords and develop the visual model demonstrated in Figure 3.1. After adding the appropriate nodes to the diagram, in 300-500 words, develop a critical reflection on your selected visual semantic worknet, using the following questions to guide you:

- What does each word or phrase mean, generally? What do they mean in the context of this specific article?

- Does the author provide definitions of the terms? More than one definition for each term? Are there examples in the article that illustrate more richly what the words or phrases do, how they work, or what they look like?

- Who uses these phrases, other than the author? For example, who are the people in the world who already know what “primary research” refers to? What kind of work do they do? Why?

Phase 2: Bibliographic Worknet—How do Sources Intersect and Draw from Each Other?

In the second phase of working with your central article, we ask you to investigate its bibliography*—the list of sources that the author of your article has paraphrased, quoted, and summarized—by selecting, finding, and skimming or reading sources from the bibliography. (Bibliographies are located at the end of research articles; they may be titled “Works Cited,” “References,” or “Bibliography,” depending on the documentation style.) You can choose any source that is found in the back matter, footnotes, or endnotes of your focal article to work with, and we recommend beginning with five or so. You might select the most significant sources—the ones that the author cited most frequently or drew from extensively—or you might simply select the ones that are most interesting to you. Either approach will be useful—they’ll just yield different results. Attention to a source’s bibliography is a way to begin tracing how sources use other sources to make their arguments. When we pay close attention to bibliographic references, we begin to see the links we might make 1) between keywords and phrases and a bibliography or Works Cited page and 2) between a central author and the sources with which they work. We begin to see that ideas don’t just happen—they are connected to ideas that came before them. This foregrounds the interconnection of the article’s main ideas and sources it draws upon, shedding light on the many ways in which academic research builds upon precedents by extending, challenging, and reengaging historical texts.

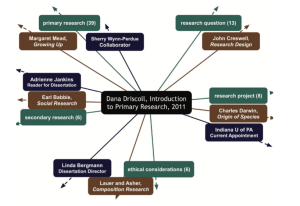

Developing a bibliographic worknet like the one in Figure 3.2 calls attention to choices the author has made to invoke specific writers and researchers and their work in the article. It tells of a deeper and thicker entanglement, a web whose filaments extend beyond the obvious references into work that has gone before, sometimes recently, sometimes long before. By involving sources in the article, the author orients what are oftentimes central ideas while also associating those ideas (via the sources) with tangible, identifiable, and (sometimes) accessible precedents. This step is like the development of an annotated bibliography, or a list of sources relevant to a research project that include brief notes about the significance of a source to a wider conversation. An annotated bibliography provides an invaluable intermediate step toward developing a literature review.

In a journal article, the sources an author cites are listed at the end of the article. Their position implies secondary relevance. And yet the references list is an invaluable resource for further tracing and for discovering, by following specific references back into the article, just how unevenly the sources become involved in the article. That is, a references list makes sources appear flat and equal, but among the sources listed, it is common to find that only a quarter of them (or even less, sometimes) figure in substantial and sustained ways throughout the article. Many others are light, passing gestures. The bibliographic worknet can help you differentiate between the two and begin to notice which sources loom large and which are but briefly invoked.

Reading along and across the sources cited is akin to following leads and accepting invitations to further inquiry, formulating new or more nuanced research questions, and discovering influences that are intertwined, eclectic, and complementary. Finding a source and reading it alongside your focus article, too, can yield insights into the highly specific and situated ways writers use sources. For example, if you’re researching climate change and just read a paraphrase or a brief quote from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration at the Mauna Loa Observatory’s 1958 data, you’ll only have a part of the story. However, if you find that data and read it yourself, you might find that there are different parts of the data that you think are important to highlight. You might have a different perspective on the research, or you might find that you better understand the original article that led you to this text. Either way, your understanding of the original article, the larger research area, and the intersection between the two sources will deepen.

Try This: Developing Your Bibliographic Worknet (1-2 hours)

After adding the appropriate nodes to your diagram (as in Figure 3.2), in 300-500 words, develop a critical reflection on your selected visual bibliographic worknet, using the following questions to guide you:

- Which of these sources are available in the library? Which are available online?

- What is the average age of the sources? What might the date of the sources say about the timeliness of the article? What is the oldest source? Which is most recent?

- Are there sources that are inaccessible or out of circulation? How did the author locate such sources in the first place?

- How did the focus article use or incorporate the source materials? Were they glossed or briefly mentioned? Were large parts summarized into thin paraphrases? Were the whole of the works mentioned or just key ideas?

- Which of the sources, judging by its title, is most likely to cite other sources in the list? Which is least likely?

Try This: Developing a Rapid Prototype (30 minutes)

Before we go farther, let’s pause and try this out. Notice that the first two phases of developing a worknet are concerned with things you will find in the source—keywords and phrases and sources cited. Work with any text you choose (an assigned reading for this class or another class or a source you can access quickly) to develop a rapid prototype, a swiftly hand-sketched radial diagram focusing only on the first two phases. You could share the diagram with someone who has read the same source and compare your radiating terms and citations. You could write about one or two of the terms or citations to anticipate their relevance to your emerging project. Or you could write about (or discuss) what the presence or absence of selected terms or sources says about the source you’ve chosen.

And/Or, Try This: Investigating Lists of Sources (1 hour)

Works cited or references lists may appear to be simple and flat add-ons at the end of an article or book, but we regard them to be rich resources for thinking carefully about a writer’s choices. Look again at the works cited or references list for your chosen article, this time with an interest in coding and sorting it. This means you will look at the references list with the following questions to guide you:

- How recent are the sources in the list? Plot them onto a timeline to indicate the year of publication from oldest to newest. Which decade do most of the resources come from?

- How many of the sources are single-authored? How many are co-authored? How many are authored by organizations, companies, or other non-human entities (i.e., not by named human authors)?

- How many of the sources come from books? How many from journals? How many are available only online? How many are published open access?

- Ethical citation practices include awareness of the kind of voices represented through the works you’ve consulted. Given that you can only know so much about an author through a quick Google search, consider what voices are included. Which voices are amplified, and which are missing altogether? You might consider developing a coding pattern to highlight the ways in which the authors represented identify in regard to gender, race, and ethnicity. Such an effort is fraught, yet it can begin to highlight patterns important for readers of sources to understand who is and is not being cited.

Among these patterns, which are significant for understanding the article, its authorship, or the contexts from which it was developed? What can you tell about the discipline or about the citation system based on coding the works cited or references list as you have?

To create a bibliographic worknet, begin by reading the references list, footnotes, and endnotes and highlighting the sources that pique your curiosity. Once you’ve sampled from the list, take your sources to your library database to see what you can find. Try to locate three to five other sources from the bibliography, noting to yourself how difficult or easy these sources were to find. Once you’ve located your bibliographic sources, take a look at the pages that your central source cited and how the ideas on those pages were used in the focal source. Put the borrowed idea in context and try to figure out how and why your central source chose the bibliographic source to work with. Sampling from a bibliography, whether purposeful or random, can lead to promising new questions and promising new sources that can inform, guide, and shape your research questions. When you compose a 300-500 word written accompaniment of the bibliographic worknet, it is in service to thinking through where sources come from, how history marks sourcework, how findable sources really are, and how authors use other sources to create their key arguments.*

By the time you’ve collected three to five sources for your bibliographic worknet and noted some emergent key terms from your semantic worknet, you will be in good shape to begin to chart the major ideas, patterns, and distinctions among a group of sources. This will help you determine which sources hang together with a kind of “idea glue” that may help you, as a researcher, figure out which sources best frame your research question and which sources are less important in framing your research direction—this is how literature reviews begin to develop.

Phase 3: Affinity Worknet—How Are Writers Connected?

In the third worknet phase, you pay attention to ties, connections, and relationships—affinities—between the central article’s author and others in the research field you are exploring. An affinity worknet takes into account where the author has worked, what sorts of other projects she has taken up, and whom she has learned from, worked alongside, mentored, and taught. Many other authors are continuing research related to the article you have read. They are also keeping the company of people who do related work, whose research may complement or add perspective to the issues addressed in the article. You can see these relationships illustrated in the affinity worknet for our sample article in Figure 3.3.

As distinct from the first (semantic) and second (bibliographic) phases, the affinity worknet moves beyond the text and citations in the article; it is informed by activity and relationships in the world that may not be evident in the article itself. It begins to explore insights into an author’s career and the interests that have shaped it. The focal article, for example, may bear close resemblance to other projects the author has worked on. Or her professional experience may suggest interplay among work history, current workplace responsibilities, and intellectual curiosities. Further, the people authors learn from and mentor are interconnected, participating in what is sometimes called an invisible college,* or a network of relations that operate powerfully and with varying degrees of formality and that influence the behind-the-scenes ways knowledge circulates throughout and across academic disciplines. The affinity worknet traces provisionally some of the shape of the collectives that have been a part of the author’s work life. When you trace these relationships, you’ll find that you have a much larger pile of sources to work from and directions for your work to follow—research centers, university programs, online forums, conference presentations, and multi-authored collaborations. As you compose a 300-500 word written record of the affinity worknet, you’ll get a sense that academic writers don’t emerge suddenly from isolation to compose rigorous work. Instead, they—like you—are real people, with real friends, colleagues, institutions, and collaborative relationships that sustain them. All of those relationships are also places that you might look to in order to orient your research project, as they offer you a glimpse into where your thinking comes from, how it is sustained, and where it gathers in space.

Try This Together: Where Can I Find Affinities? (30 minutes)

Among the central premises in the affinity phase is that we can learn something about a writing researcher by noticing the company they keep. That is, by looking into professional and social relationships that have operated in their lives, we can begin to understand the larger systems of which their ideas—and their research commitments—are a part.

To treat this as its own research question would be to ask the following: What kinds of relationships can we learn about and by what means can we learn about them? Certainly simple Google searches may provide a start, but where else might you look? Work with a partner to generate a list of possible leads—platforms or social media venues where you might check to find out more about the lead author of the article you’ve chosen to work with.

Where can you find information about an author’s affinities? A Google search for the author’s name may lead you to an updated and readily available curriculum vitae, which is like an academic resume. Such a search might also lead to the author’s social media activity (Facebook or Twitter accounts) or to a professional web site that provides additional details about collaborations and relationships. For perspective on intellectual genealogy related to a doctoral dissertation, you can turn to your library’s database resources page and look into ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global, which indexes information about major graduate projects and the people who participated on related committees. This lead can yield insight not only into who the author is and how she is connected to others but also into where an author’s work comes from in the earliest stages of her career. You’ll finish the affinity worknet having both a larger repertoire of research strategies and a wealth of people and places to lead you to other sources that you might not have otherwise thought of.*

Finding these affinities will also help you hone your research skills, allowing you to see that lives and connections can be traced through sources other than traditional library databases.

Try This: Writing about Your Affinity Worknet (1-2 hours)

After adding the appropriate nodes to the diagram (as in Figure 3.3), in 300-500 words, develop a critical reflection on your selected visual affinity worknet, using the following questions to guide you:

- What other kinds of work has this author written? When? For what audiences and purposes?

- Does the article in question bear resemblance to their other research? Does it seem to inform or influence their teaching or other responsibilities?

- Who has the author collaborated with on articles or on grants? What are the research interests and primary disciplines of these collaborators?

- Does the author appear to be active in online conversations? Where, and what do these interactions appear focused on? Are they professional and research-related or more casual and social?

- Where did the author study? With whom? What might be some of the ways these places and people influenced the author?

Phase 4: Choric Worknet—How Is Research Rhetorically Situated in the World?

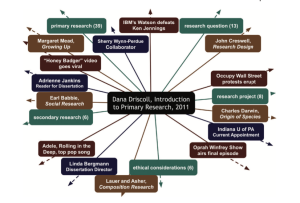

With the fourth phase, worknets grow curioser, adding to the mix what we identify as choric elements. Choric elements take into account the time and place in which the article was produced. Choric worknets gather references to popular culture, world news, or the peculiarities and happenings that coincided with the article’s being published. The term choric comes from the Greek, khôra, the wild, open surrounds as yet-unmapped and outside the town’s street grid and infrastructure. Notice, too, the word’s associations with chorus, or surrounding voices. With this in mind, we regard the choric worknet as exploratory and playful, engaging at the edges so that readers might wander just a bit. Sometimes our best ideas are those that seem, at first glance, to be farfetched.

Compared to the other phases, the choric worknet orbits in wider and weirder circles, drifting into uncharted and therefore potentially inventive linkages. Considering the time and place in which an article was written helps bring us as readers to that time and place. Venturing into the coincidental surrounds can lead to eureka moments, inspiring clicks of insight, curiosity, and possibility, but it can also prove to be too far flung, too peculiar to be useful. This is one of the lessons of research: sometimes we spend time on what we think will be useful, but as any Googler-down-the-rabbit-hole- of-YouTube knows, sometimes what we think will be useful isn’t. Yet it is in the trying that we learn how to weed out as well as how to hold close what is exciting, original, and odd.

This phase encourages you to find those rabbit holes, if only for a moment. Begin with the year your focal article was published, where the author wrote it, and begin an online search, paying attention to what was happening in the world that year. Follow your hunches, your interests, and even the ways that what you’ve found in the other worknet phases maps on to where your meandering is going. Look at Figure 3.4 and you will see five choric nodes. Their selection came from 30 minutes of online searches related to 2011, primarily, and also a few related to Southeast Michigan, Detroit, and Oakland University, the university where Dana Driscoll worked when she wrote the article. Each of the five nodes reflects your choice, something noteworthy or intriguing.

The choices you make in creating the nodes can spark the beginnings of researchable questions and may be reflected in your 300-500 word account of the choric worknet. For example, the node for the “Honey Badger” video going viral as it coincides with Driscoll’s article on primary research methods might instigate research questions concerning just what kind of researched claims the video makes, the relationship of video to writing, and the edge of seriousness and playfulness in composing research that will circulate publicly. This element in the choric worknet, although it at first may seem trivial, can also pique curiosity and invite inquiries into what animals know or into their biology and ecology, such as in the This American Life podcast episode, “Becoming a Badger.” For any student who began reading their focal article with few ideas about their own research path, the choric phase will give you an abundance of options to test and play with the limits and openings of a research project.

Given the messiness of invention—its combinations of purpose and digression, insight and failure, getting lost and then deciding on a direction— the choric worknet stands as the most wide open, potentially the richest of the four phases, even as it risks being the most wasteful, inviting oddball and offbeat ties. Such ties, however, situate the article in the wider world, and they do so while also honoring the place you stand as a researcher, tapping into the interests and curiosities that compel you most.

Try This: Writing about Your Choric Worknet (1-2 hours)

After adding the appropriate nodes to the diagram, in 300-500 words, develop a critical reflection on your selected visual choric worknet, using the following questions to guide you:

- What was happening in the wider world coincident with the time and place of the focal article’s being written and published?

- Why have you selected the assortment of nodes you have? How did you find them? What about them compelled you to add them to the worknet?

- Where do you locate possibilities for further exploration and for emerging interests at the juncture of any choric node and any other node in the radial diagram?

- Which of the choric nodes is most relevant, in your view? Which is least?

- Are there choric nodes you thought about including but later abandoned? What motivated you to make such choices?

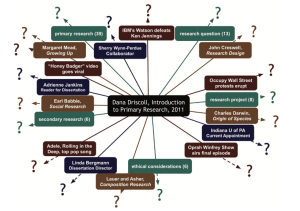

Branching Out—Taking Worknets Farther

With the four phases completed, as in Figure 3.5, the worknet introduces initial, inventive branchings, a web of filaments, or trails, that invite further inquiry and that may prime further questions. When experienced researchers read scholarly sources, they usually do so to support, reinforce, or clarify claims they have already begun to formulate. In early stages of research, however, reading scholarly sources oftentimes yields more questions, and these questions each set up further inquiry. Worknets position scholarly sources as resources for invention, and after developing all four phases, you will begin to see that you have many more options for expanding your emerging interests than you initially realized. This approach resonates with the idea of copia,* or lists of possibilities, which suggests that having more than you need to continue research is a wonderful place to be.

While a single worknet can engage us with new ideas entangled in a web of relationships extending from an article, a series of worknets—that is, worknets applied to two or three or more related articles—can form the foundation for a substantial backdrop to a research project. In fact, a compilation of worknets provides you with the basis of a literature review, that portion of a researched project that provides orientation to established research related to your area of inquiry.

Really Getting to Know Your Sources

Worknets provide a stepwise process to get to know your sources. The better known and better read the sources, the more nuanced and precise will be the literature review that emerges from your work with them. Certainly there are other intermediate note-keeping options and less involved approaches to the phases presented in this chapter. For example, an annotated bibliography might require you to gather and write brief summaries of related sources, focusing on the relevance of the source to your research question. Whether you take up the method we introduce and produce a full, complete worknet for one source, or whether you apply selections of the phases to one or more articles, perhaps adapting by writing annotations or sketching worknets by hand, the approach introduced here will help shape your own work.

Try This: Finding Connections, Near and Far (30 minutes)

The choric nodes are the most likely to introduce variety and surprise. They fan out the article’s web of relations, finding (possible) connections that may hint at new or slightly altered researchable questions. After you develop the choric phase of the worknet for your chosen article, identify both the node you consider to be most related and the node you consider to be least related. Write for five minutes on each node, accounting for why you think it to be more or less related. What do each of these nodes indicate about the world from which the article emerged? What do each of these nodes say about what you find interesting or about your own curiosities in this context?

Modeling Worknets

We have seen students do distinctive, innovative work with worknets, and we’re spotlighting one such example to give you an idea of what is possible. One undergraduate student at Virginia Tech applied all four phases to a 2015 article by Armond Towns, “That Camera Won’t Save You! The Spectacular Consumption of Police Violence.” The article discusses issues related to body cameras, social justice, police violence, and the presumed security bestowed on technological devices. In this case, the worknet followed the steps introduced in this article, culminating in all four phases layered into Figure 3.6.

Additionally, the student was invited to translate the visual and textual worknet into a 3D model, using materials from a local art supply store. The model materialized the worknet as a physical sculpture, conveying more fully an understanding of the article as entangled with the words, sources, relationships, and time-place coincidences of the moment in which it was produced. Figure 3.7 shows the potential of extending the worknet one step farther by creating a model whose dimensions and materials exceed the page or the screen.

Using Worknets to Develop a Literature Review

Although literature reviews serve different purposes from discipline to discipline and vary in scope from one project to another, they have in common the purpose of orienting readers to relevant scholarship. Literature reviews provide a synthesis, or glancing overview, that weaves together relevant focuses and acknowledges limitations, or knowledge gaps, in the series of sources gathered in the review. By the time you’ve finalized a worknet, you will have read and skimmed at least ten sources around a common research theme and question that interests you. Looking again, consider some of the ways specific worknet phases can support your development of a literature review:

- Semantic worknet (phase 1): How are specific keywords and phrases used differently from one source to another? How do different keywords and phrases across a selection of sources suggest yet more refined possibilities for impactful terms not yet introduced in the sources gathered?

- Bibliographic worknet (phase 2): How do the articles you have collected respond to common sources? What can be said about each article’s timeliness based on the ages of the sources it consults?

- Affinity worknet (phase 3): How do connections with other people or institutions reveal the priorities of the authors of your sources? What can you discern about the relationship of each article to an academic discipline?

- Choric worknet (phase 4): What is the relationship of each article to contemporary events? How might those events have influenced its message?

With a series of worknets built from different but related sources, you have carried out a generative, robust method for assembling, annotating, and interweaving sources. Literature reviews require thoughtful balancing of sources, making reference to sources so they are represented concisely and fairly. Worknets, for the practice they give you with moving in and out of texts, support the development of effective literature reviews.

Focus on Delivery: Writing a Literature Review

A literature review is a synthesized grouping of academic sources that have been chosen to frame a larger piece of research and that relate to a research question a writer is pursuing. Some literature reviews are stand-alone pieces to say “this is what’s out there on a particular topic.” Most literature reviews are front matter for larger academic papers. The scope of your project will determine how many sources go into your literature review.

By “literature,” we mean academic scholarship chosen about a certain topic that helps to answer a particular research question. By “review,” we mean a summary of the literature’s argument and an explanation of its connection to the other sources that you use.

To write a literature review, complete these steps:

- Locate five to ten sources that you think would be useful for understanding the research question.

- Skim these sources.

- If the source is relevant to your research question, read it fully and annotate it, writing a 100-word summary of the source in your own words. Read the source’s bibliography to add relevant sources you find there to your working source list.

- Discard irrelevant sources and locate ones that are more specific to your research question. Annotate all relevant sources.

- Read your 100-word summaries and try to figure out how they go together. What are their common features, key words, and theoretical frameworks? What year were they written? Could sources be grouped historically, theoretically, or thematically?

- Use your worknets to help you group your sources in different ways in order to see patterns between and among your sources:

- What similar ideas and words are used to discuss major ideas in your research area among your sources? How do they differ? (semantic)

- What changes when you move your sources into chronological order from earliest to latest or latest to most recent? (bibliographic)

- What happens when you group sources by relationships between and among sources? (affinity)

- Would your review benefit from adding historical and cultural context? (choric)

- Consider how these sources together lead up to your research question. Why is it important, timely, and relevant to previous research?

- Revise your annotations and put them together in such a way that the connections between them are clear and the connections to your research question are visible.

What’s important for you to know about literature reviews is that the choices about what sources to use and what makes them go together are not immediately clear for a reader, which means part of writing a literature review is including that rationale within the review itself. By reading your literature review, your audience should be able to figure out the “idea glue” that holds all of the literature together, inclusive of your project’s purpose and the main conversations taking place within your research area. A reader should walk away from your literature review knowing exactly why you’ve chosen these sources to go together, as opposed to millions of others that could be chosen instead.

Works Cited

Driscoll, Dana L. “Introduction to Primary Research: Observations, Surveys, and Interviews.” Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, edited by C. Lowe and P. Zemliansky, vol. 2, WritingSpaces.org/Parlor Press/The WAC Clearinghouse, 2011, pp. 153-74. The WAC Clearinghouse, wac.colostate.edu/docs/books/writingspaces2/ driscoll–introduction-to-primary-research.pdf.

Glass, Ira, host. “Becoming a Badger.” This American Life, episode 596, WBEZ, 9 Sept. 2016, www.thisamericanlife.org/596/becoming-a-badger.

Johnson, Alonda. “3D Model of Worknet for Armond Towns’ ‘That Camera Won’t Save You! The Spectacular Consumption of Police Violence.’” 14 Nov. 2018.

ENGL1105: First-year Writing: Introduction to College Composition, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, student work.

Johnson, Alonda. “Worknet of Armond Towns’ ‘That Camera Won’t Save You! The Spectacular Consumption of Police Violence.’” 14 Nov. 2018. ENGL1105: First-year Writing: Introduction to College Composition, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, student work.

Towns, Armond R. “That Camera Won’t Save You! The Spectacular Consumption of Police Violence.” Present Tense: A Journal of Rhetoric in Society, vol. 5, no. 2, 2015, www.presenttensejournal.org/volume-5/that-camera-wont-save-you-the-spectac-ular-consumption-of-police-violence/.

“Trends in Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide.” Carbon Cycle Greenhouse Gases, NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratory, 5 Oct. 2021, gml.noaa.gov/ccgg/trends/.