Lab 8: Biodiversity Challenges: Deer Population

Introduction

The focus of this lab is to provide an opportunity to explore concepts related to biodiversity including understanding the idea of biodiversity, analyzing threats to biodiversity, exploring biodiversity issues in the urban/suburban setting, understanding the strategies and challenges in conservation biology, and evaluating the role of humans in the management of native wild species and their habitats, such as is pictured in Figure 8.1 above. We will primarily explore these concepts through case studies of white-tailed deer populations (Odocoileus virginianus).

Lab Objectives

In this lab, you will:

- Describe ways that humans have historically impacted the deer population.

- Gather and summarize information on how deer populations impact their ecosystems from expert sources.

- Explain the information presented about deer populations from charts and graphs.

- Assess the various goals and concerns of diverse stakeholders with regard to deer populations.

- Construct a plan to manage the deer population in response to both the ecological knowledge you have acquired and the stakeholder opinions that have been presented.

Part 1: Research—Should white-tailed deer populations be managed?

Visit the Illinois DNR website on white-tailed deer.

As a group, read and discuss the Deer Ecology section of the website and the page Why Manage? Be sure to spend some time looking through the rest of the website, as nearly every page has helpful information.

Use the website or other expert sources to answer the questions in Part 1: Should white-tailed deer populations be managed? section of the Lab Response form.

Be prepared to summarize your group’s comments in a full class discussion.

Part 2: Data Analysis—Outcomes of white-tailed deer management

Let’s take a deeper look into the subject of how deer populations impact their ecosystems.

Prior to European settlement, deer densities in North American forests were roughly 8-11 deer per square mile. In contrast, recent monitoring efforts have shown that deer densities in many eastern parks exceed 100 deer per square mile. Simultaneously, vegetation monitoring indicates a decline in tree seedling and sapling densities, which deer exclusion studies make plain is the result of deer browsing (or feeding behavior).

To recover from any type of disturbance, healthy forests require adequate tree seedlings and saplings to enable regeneration of the forest canopy. However, many long-term datasets (such as those from the National Park Service Inventory and Monitoring Division) indicate that decades of over-browsing by white-tailed deer have prevented tree regeneration in many eastern national parks. Most of the preferred foods for deer are native plant and tree species, so herbivory pressure in areas of high deer density results in non-native invasive species flourishing. Deer-dominated forest ecosystems tend to shift towards thickets of invasive shrubs as canopy trees decline from disturbances or age. The end result is that without deer management, parks are at risk of losing their forests. If a disturbance such as storm damage or insect infestation takes out mature trees, the forest will be unable to reestablish itself.

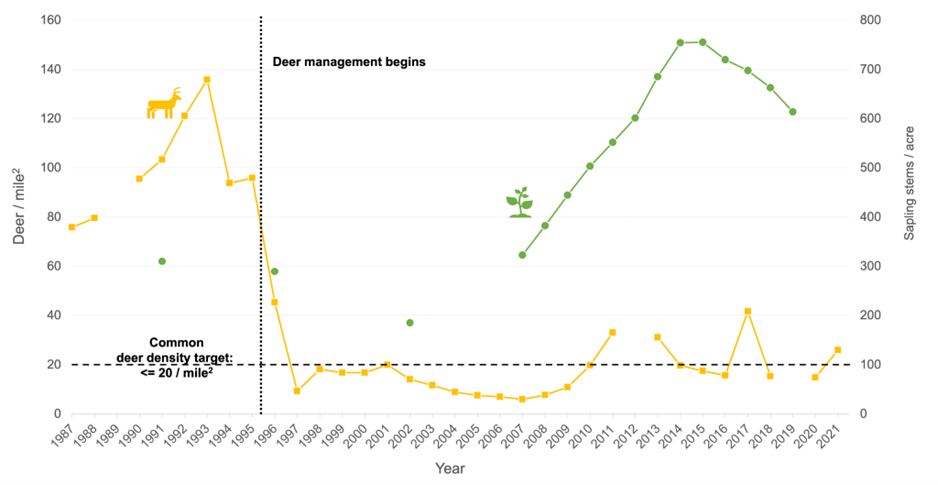

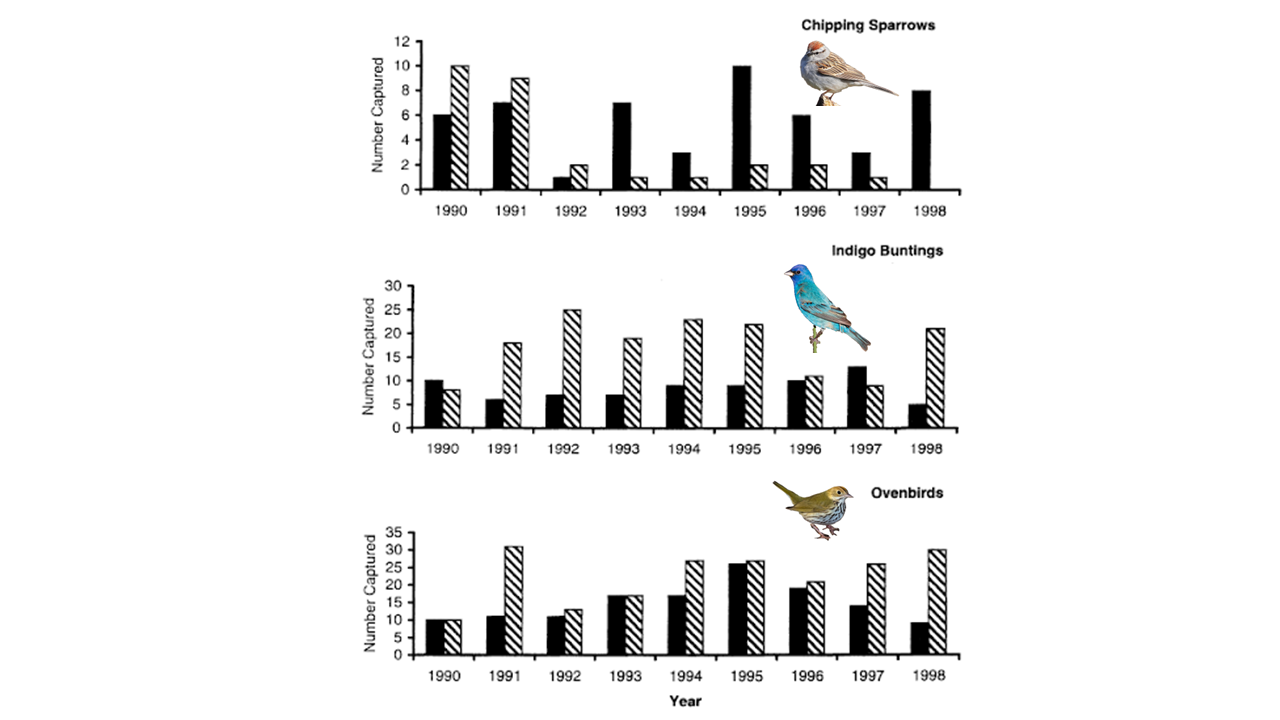

We’ll examine the results of deer management programs on seedling recovery in two parks: Gettysburg National Military Park in Pennsylvania and Catoctin Mountain Park in Maryland. The graphs presented here are from Case Studies in Deer Management StoryMap (Weinberg McClosky, ND) and are based on data from the National Park Service Resilient Forests Initiative for Eastern National Parks. Read the two summaries below, examine the graphs, and answer questions in Part 2: Data analysis—Outcomes of white-tailed deer management and Part 3: Analyze and Explain: What population control practices should we use? of your Lab Response form.

Gettysburg National Military Park

The landscape at Gettysburg National Military Park in south central Pennsylvania includes a combination of open fields, farmland, and woodlots that are dominated by white oak, ash, and hickory. To help visitors connect with historic events, the park endeavors to maintain the landscape as close to what it was when the battle was fought. Beginning in the 1970s and 1980s, park staff observed an increase in the size of deer herds feeding in the park’s agricultural areas. At the same time, they also noticed a lack of young trees in the woodlots and speculated that the deer were browsing on the seedlings and saplings as well. Due to concerns about forest regeneration and the role that deer might play in it, they began a long-term vegetation and deer monitoring project.

What researchers from Gettysburg Park and Pennsylvania State University found was that by 1992 deer densities exceeded 100 per square mile. Simultaneously, vegetation monitoring showed that tree seedling and sapling densities were declining, and comparisons of fenced (deer exclusion) and unfenced plots provided evidence that the declines were due to deer browsing. These studies concluded that deer density in Gettysburg would need to be reduced to 25 deer per forested square mile to allow for adequate survival of seedlings and saplings to maintain the woodlots. In 1995 the park completed an environmental impact statement that specified lethal removal of deer as the best deer management pathway to achieve the recommended density, and the first removals began later that same year (NPS, 1995). Reference Figure 8.2 below, which displays a relationship between the deer population density and the number of seedlings in the area.

Catoctin Mountain Park

Established during the Great Depression, Catoctin Mountain Park in Maryland protects both natural areas and cultural resources. Though despoiled by industry and agriculture, the park’s forests have successfully recovered and today offer a wide range of outdoor recreation opportunities.

As the forests recovered, so did the deer population, and by the 1980s, park staff were concerned about the impact of deer herds on the forest ecosystem. Young trees as well as understory plants and wildlife all seemed to be impacted, and the state-threatened greater purple fringed orchid needed the protection of deer exclusion fencing. Figure 8.3 below displays the population of three bird species at four deer exclosure sites (areas that the deer cannot access) and four control sites.

Thus in 2009, based on long-term studies validating the undesirable effects of a large deer population, the park finalized an environmental impact statement that included the use of fencing, repellents, as well as the lethal removal of deer to maintain a winter population of 15–20 deer per square mile. At the time the EIS (NPS, 2009) was finalized, the deer numbered over 120 per square mile in the park. Since then, park staff survey the deer population each November and determine the deer management plan that will achieve the target density of 15-20 deer per square mile.

Answer the questions in the Part 2: Data Analysis—Outcomes of white-tailed deer management section of the Lab Response form.

Part 3: Analyze and Explain—What population control practices should we use?

Conflicts over the management of abundant wildlife have increased dramatically over the past decade. Some residents enjoy the presence of white-tailed deer in their neighborhoods, while others have become concerned about problems deer may cause. Here we focus on the challenges faced by wildlife managers and community decision-makers in reducing the negative impacts associated with high deer densities. Especially in highly populated areas like DuPage County, the traditional management method of hunting is infeasible (as it is unsafe to discharge firearms in areas with high human population density), or socially unacceptable (as the general public will not enjoy watching deer die), and community members hold diverse wildlife values. Instead, here are four potential methods for managing deer that are being considered.

Read, consider, and discuss the four possible methods of deer population control presented below. As a group, decide which method is the most practical, answer the Lab Response questions, and create a plan to deal with the white-tailed deer population for your model community.

Method 1: Selectively Cull Deer

The deer population could be reduced by selectively shooting deer attracted to a carefully designed bait site. The meat from a deer cull can be donated to charitable organizations. Deer could be culled by professional sharpshooters or village police. Sharpshooters could use shotguns or archery equipment (bow and arrow) to shoot deer. The cost of this technique is estimated to be around $300 per deer. Wildlife scientists say this technique is effective for immediate reduction of deer numbers in small areas. However, this technique may be difficult in Cayuga Heights because of the density of buildings and houses and because of safety concerns. Sharpshooting is estimated to reduce adult and yearling deer survival by 54-76% (DiNicola and Williams 2008).

Method 2: Deer Contraception

Contraception, or birth control, for female deer is still being perfected, so any decision to use contraception must be part of a research project. The estimated cost of contraception is around $1,000 per deer to administer two treatments per year for two years. Contamination of the food chain and meat butchered by hunters is possible. Several contraceptives are used and generally administered to deer with a dart gun. If any darts miss their mark and go unrecovered, they could be hazardous to humans. The effectiveness of reducing population levels using this method is uncertain but estimated to result in 80-90% reduction in fawning for treated females.

Method 3: Surgically Sterilize Deer

Surgically sterilizing female deer is another possible means to attempt to reduce the population of deer. The cost of this method is estimated to range from $400 to $600 per deer—depending on the success rate and the method used to capture deer—after an initial outlay of around $20,000 for equipment. The long-term effects of this method on deer behavior and genetics are unknown. Sterilization has been successful in over 90% of the cases, with successfully treated females becoming unable to have offspring. However, reproductive tissues have been observed to grow back in some individuals. Individual deer only need to be treated once, but it is difficult to capture all deer, especially when there is movement between deer populations. Previous studies have demonstrated that capturing 45-80% of female deer in a population is necessary for sterilization to be effective (Merrill et al. 2006, DeNicola and DeNicola 2021).

Method 4: Educate People About Reducing Deer-Related Problems

One possible decision is to do nothing to reduce the deer population directly, but to try to teach people to reduce problem interactions by changing their behavior or the behavior of deer. The costs for this approach would depend on how much, if any, of an education campaign was funded by the county. Methods that could be promoted include installing deer fencing, planting unpalatable landscape plants, using deer repellents, discouraging deer feeding, and hazing or frightening deer. County ordinance prohibits installing fences over 4 feet in height within the first 15 feet of one’s property. Most methods of problem prevention have low levels of effectiveness, and none are considered fool-proof.

Part 4—Create: Your White-Tailed Deer Management Proposal

Once you have completed Parts 1-3 of this lab and heard other groups’ perspectives, go to Part 4: Create—Your White-Tailed Deer Management Proposal in the Lab Response form. Ensure that you address each of the following:

- After discussing your group’s various viewpoints, document your discussion and decisions via the case management plan.

- Be prepared to present and explain your responses to the class, using notes from your discussion as well as the information you have summarized in Parts 1-3 of your Lab Response form.

References

DeNicola, A. J., & DeNicola, V. L. (2021). Ovariectomy As a Management Technique for Suburban Deer Populations. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 45(3), 445–455. https://doi.org/10.1002/wsb.1218

DeNicola, A., & Williams, S. (2008). Sharpshooting Suburban White-Tailed Deer Reduces Deer–Vehicle Collisions. Human–Wildlife Interactions, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.26077/cqnd-nc30

McClosky, J. W. (2022, December 28). Case Studies in Deer Management. ArcGIS StoryMaps. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/5b5fe3b82f664093ad435040724706ef

McShea, W. J., & Rappole, J. H. (2000). Managing the Abundance and Diversity of Breeding Bird Populations through Manipulation of Deer Populations. Conservation Biology, 14(4), 1161–1170. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1739.2000.99210.x

Merrill, J. A., Cooch, E. G., & Curtis, P. D. (2006). Managing an Overabundant Deer Population by Sterilization: Effects of Immigration, Stochasticity and the Capture Process. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 70(1), 268–277. https://doi.org/10.2193/0022-541X(2006)70[268:MAODPB]2.0.CO;2

National Park Service. (1995). Record of Decision on the White-Tailed Deer Management Plan Final Environmental Impact Statement for Gettysburg National Military Park/ Eisenhower National Historic Site, Pennsylvania. Federal Register, 60(134), 3159–3161. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/1995/07/13/95-17226/record-of-decision-on-the-white-tailed-deer-management-plan-final-environmental-impact-statement-for

Lab 8 Response: Biodiversity Challenges: Deer Population

Download this Lab Response Form as a Microsoft Word document.

Part 1: Research—Should white-tailed deer populations be managed?

- Use bullet points to fill out the table below with information about white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) from the Illinois DNR website or another credible source. Make sure that each piece of information is cited.

|

Topic |

Information |

Source (Author, Page Title, Link) |

|---|---|---|

|

List three facts about their reproductive cycle. |

|

|

|

List three traits of their preferred habitat. |

|

|

|

List three concrete problems deer populations pose to the ecosystems they inhabit. |

|

|

|

List two possible threats deer populations pose to human populations. |

|

|

|

List two possible ways deer overpopulation impacts the deer themselves. |

|

|

Answer the next two questions:

- How have humans changed the environment to favor the population of white-tailed deer? Explain your answer using evidence from your chart.

- Should humans play an active role in white-tailed deer management? Why or why not? List your reasons, using evidence from your chart.

Part 2: Data analysis—Outcomes of white-tailed deer management

In your lab group, describe and analyze Figures 8.2 and 8.3 from the Lab Activity and be prepared to share your responses to the following questions in a full class discussion:

- Describe both graphs. What story is each telling about the ecological impact of deer populations? How are they similar? How are they different?

- What conclusion can you draw regarding the effect of deer management on seedling numbers?

- What conclusion can you draw regarding the effect of deer management on the 3 different bird species?

- What predictions would you make about sustainable forest regeneration in the future in these two forests? Brainstorm challenges that could potentially impact forest regeneration. What information would you need to make a more informed conclusion?

Part 3: Analyze and Explain—What population control practices should we use?

Your group will be assigned one of the following stakeholder groups:

- Hunter

- Environmental activist

- Corn farmer

- UPS truck driver with a rural route

- Suburban householder who works from home and lives in a recently developed subdivision built upon former farmland fields

- What environmental (in general) interests or concerns might your stakeholder group hold? Explain why this is the case.

- How do deer impact the lives of your stakeholder group? What deer-driven concerns would your group have?

- What concerns might the stakeholder have about different methods of population control?

Present your stakeholder’s viewpoint to the rest of the class by summarizing your group’s answers to the three questions above.

Part 4: Create—Your white-tailed deer management proposal

Once you’ve heard the information from the different stakeholder groups presented to the class, your group should create a white-tailed deer population management proposal that reflects all of the stakeholders’ viewpoints. What method or combination of methods should the Illinois Department of Natural Resources Division of Wildlife Resources deer manager (State DNR, wildlife & recreation departments, etc.), plan to use to manage the deer population in your area or region? Discuss your plan’s potential effectiveness, cost, safety, acceptability, and humaneness.

- Why did your group make the choices you did? How did your group achieve consensus on a plan? Consensus means that the decision is one that everybody agrees with or, at least, can live with.

- Present and discuss deer management plans: Present your deer management plan to the rest of the class. After the presentations we will discuss all the plans as a class, and we will attempt to come to a consensus as a class.