8 Module 8: Testing and Intelligence

Activate

- Did you take the SAT or the ACT? Have you ever taken an intelligence test?

- Do you think that tests of intellectual ability (for example, SAT, ACT, intelligence tests) do a good job of predicting who will be successful in school and in life?

- If the answer to the previous question is “no,” what abilities (besides “intellectual” abilities) might help people to succeed in school and in life?

CogAT, Iowa Test of Basic Skills, Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, SAT, ACT, General Chemistry, Principles of Economics. At your school, students may be required to take exams to place them into the correct English and math classes, and to determine if they are skilled at college-level reading. You may face standardized tests when you begin and when you finish at the college in order to assess the effectiveness of the curriculum. And, of course, nearly every college class offers two to three exams of its own.

Even after college, you will not be done with tests. Cognitive ability tests, skills tests, even personality tests and integrity tests are all used as part of the employee selection procedure at many companies. If you decide to earn an advanced degree, you may be required to take another standardized test such as the LSAT, GMAT, MCAT, or GRE. And of course, if the current projections that most people will be required to return to school for retraining at various times during their careers are correct, you are likely to continue to face the dreaded midterm and final examinations in courses throughout your life.

For better or worse, we have entered an era of unprecedented testing. Many states require college placement exams of all high school students. Elementary schools begin preparing their students for third grade abilities tests as early as kindergarten. This module describes the good and bad aspects of tests, primarily tests of intellectual ability. Section 8.1 introduces you to the principles of test construction and how they apply to standardized tests and course exams in school. Section 8.2 takes up the question of what intelligence tests measure and fail to measure; it also discusses a couple of views of intelligence that characterize it as a set of separate abilities, rather than as a single trait. Because tests can be difficult, unpleasant, and very important, many students suffer anxiety as a result of them. This module concludes with Section 8.3, a discussion of test anxiety and the effects of stress on memory.

8.1. Understanding Tests and Test Construction

8.2. Measuring “Intelligence”

8.3. Test Anxiety

READING WITH PURPOSE

Remember and Understand

By reading and studying Module 8, you should be able to remember and describe:

- Aptitude and achievement tests (8.1)

- Standardization, reliability, and validity (8.1)

- Cattell-Horn-Carroll (CHC) theory and its organization (8.2)

- Successful Intelligence: analytical, creative, practical intelligence (8.2)

- Test bias (8.2)

- Stressors (8.3)

- Effects of stress and anxiety on memory and testing ability (8.3)

- Relaxation techniques for test anxiety: STOP technique, progressive relaxation (8.3)

Apply

By reading and thinking about how the concepts in Module 8 apply to real life, you should be able to:

- Recognize standardization, reliability, and validity in exams you encounter (8.1)

- Recognize examples of the Cattell-Horn-Carroll (CHC) theory (8.2)

- Recognize examples of Robert Sternberg’s Successful Intelligence (8.2)

Analyze, Evaluate, and Create

By reading and thinking about Module 8, participating in classroom activities, and completing out-of-class assignments, you should be able to:

- Combine elements of different definitions and theories to come up with your own definition of intelligence (8.2)

- Identify whether anxiety helps or hurts you on exams, and devise a strategy to manage it if necessary (8.3)

- Describe the important elements you would include in a test to predict success in school and career (8.1 and 8.2)

8.1 Understanding Tests and Test Construction

Activate

- Have you ever taken a test and felt that you knew more than you were able to demonstrate on the test?

- Do you consider yourself a good or a poor test taker? If good, what makes you good? If poor, what makes you poor?

Many students complain that tests—standardized tests in particular—do not reflect their actual talents, knowledge, and abilities. These students assert that they are poor test takers who know much more than their test scores indicate. They worry that being bad at taking tests will unfairly impede their academic and work careers, because so many decisions that affect a person’s status in life are based on test scores. Although it will not entirely solve the problem, understanding a few things about tests might help demystify them and help you cope with them.

Entrance, placement, and job selection tests are all designed to do one thing, predict your future success at some endeavor. Tests that are designed to predict some future performance are called aptitude tests. College aptitude tests (SAT, ACT), for example, are designed to predict your college first semester freshman year grade point average. They are, at least in principle, different from the kinds of tests that you take in your classes at school. These other tests are called achievement tests. Achievement tests are designed to measure whether you have met some particular learning goals (e.g., did you learn the material from Chapter 6 of your History textbook).

Aptitude tests are not supposed to reflect achievement, but they often do. Some of the best-known so-called aptitude tests, such as the SAT, have been found to rely too much on the knowledge that people learn from their environment to be true measures of one’s potential. Thus, you should always keep in mind that the terms aptitude tests and achievement tests refer to their intended uses only, not to any principles related to their construction or the things they actually measure. In order to avoid confusion, we will rarely use these terms and refer instead to specific types of tests—for example, college entrance tests (SAT, ACT), and course exams.

aptitude test: a test designed to predict the test taker’s future performance

achievement test: a test designed to measure whether the test taker has met particular learning goals

Three Key Testing Concepts

College entrance tests, along with other aptitude tests, are generally standardized tests. These are tests given to people under similar testing conditions and for which individual scores are compared to a group that has already taken the tests. Let us look carefully at three key concepts that apply to many tests: standardization, reliability, and validity.

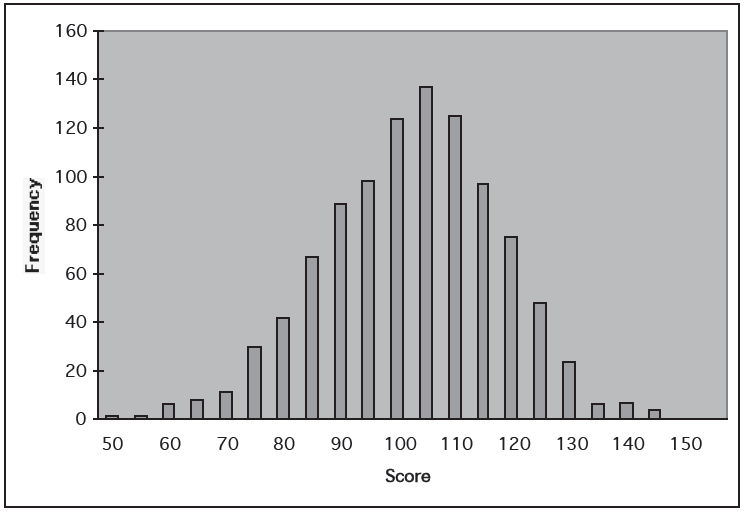

Standardization refers to the procedure through which an individual’s score is compared to the scores from people who have previously taken the test. Typically, a test will be given to a large group of people (several thousand). The scores from this standardization group are distributed in the form of the famous “bell curve.” That is, most of the scores will cluster near the middle, at the average score. There will be fewer and fewer people who score farther away from the average score. A chart of this distribution looks like the outline of a bell:

By using this distribution of scores, it is possible to estimate an individual’s score relative to the standardization group with great precision. In order for standardization to work—that is, to be able to pinpoint the individual’s performance relative to the standardization group—the testing conditions must be similar for all test takers. That is why these tests are timed, with everyone taking the test in nearly identical settings.

The second important concept in standardized testing is reliability, which refers to the consistency of a test. If a test is to be a good predictor of your future performance, it should be a consistent, or stable, predictor. It would not be very useful if the test predicted straight A’s for you on a Tuesday but a D average for you on a Friday. In order to assess the reliability of a standardized test, psychometricians (psychologists who construct tests) examine two types of consistency:

- Consistency over time is often assessed by measuring test-retest reliability. The concept is very simple. Give a group of people the test today, and then give it to them later, say, three months from today. If the test is reliable, individuals in the group should receive close to the same score both times.

- Consistency within the test is assessed by measuring what is known as internal consistency reliability, or how well the different parts of a test agree with one another. If one section of a test of verbal ability indicated that you have above-average verbal ability, it would not make sense if another section of the test indicated below-average verbal ability.

There is an important relationship between reliability and standardization. Specifically, failure to standardize the procedures by which a test is administered will lead to unreliability. For example, if a group of test-takers is given more time in a more comfortable room the second time they take a test, then test-retest reliability will be low (because they will likely score much higher on the retest).

The third important concept in standardized testing is validity, which refers to the degree to which a test measures what it is supposed to measure. It is the most complex of the three concepts. We will focus on two particular kinds of validity:

- Content validity in essence rephrases the question “Does the test measure what it is supposed to measure?” to be “Does the test look like it measures what it is supposed to?” Specifically, content validity is a judgment made by a subject-matter expert that a test adequately addresses all of the important skills and knowledge that it should.

- Predictive validity rephrases the question to be “Does the test predict what it is supposed to predict?” Obviously, then, it is principally of interest when we are talking about aptitude tests. For example, the SAT and ACT are designed to predict your college GPA. The measure of a tests’ success at doing that is its predictive validity.

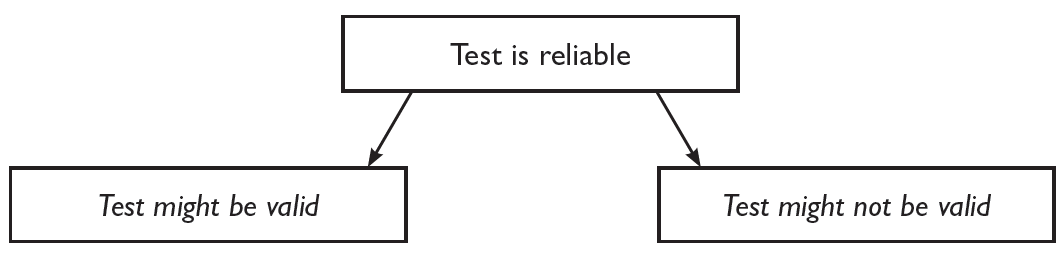

There is an important relationship between reliability and validity. If a test is reliable, we can say nothing about whether it is valid or not. Think about it. A test can be extremely reliable (consistent) yet be a very poor predictor. For example, your shoe size is reliable but not a valid predictor of your grade in this class (of course, your instructor’s job would be much easier if it were valid!).

On the other hand, if a test is unreliable, we can say something about its validity. An unreliable test cannot be valid. If a test is not consistently measuring anything (which is what being unreliable means), then it certainly cannot be a good predictor. Thus, reliability is necessary but not sufficient for a test to be valid.

standardization: comparing a test taker’s score to the scores from a pre-tested group

reliability: the consistency of a test

test-retest reliability: a technique for measuring reliability by examining the similarity of scores when the same individuals take a test multiple times

internal consistency reliability: a technique for measuring reliability by examining the similarity of an individual’s sub-score for different parts of the test

validity: whether a test measures what it is intended to measure

content validity: a technique of estimating validity by having an expert judge whether the test samples from an appropriate range of skills and knowledge

predictive validity: a technique of estimating the validity of an aptitude test by comparing test-takers’ actual performance on some task to the performance that was predicted by the test

The Properties of Course Exams

So, how do the tests with which you may be familiar fare on the three important test construction properties? First, let us consider course exams. It is important to realize that college professors are not psychometricians. Nonetheless, an informal kind of standardization often does occur. Instructors try to administer tests in similar conditions every time, and they often adjust their results to report scores relative to the rest of the class (when you are graded on a curve). This is similar to, but not the same as, standardization.

It is difficult to make generalizations about the reliability of course exams. It is probably safe to say that reliability is a problem for many course exams because there are so many specific threats to reliability. First, although instructors try, it is difficult to standardize procedures. Some classrooms are cold and noisy, others are comfortable and quiet. Some class sections meet twice a week for an hour and a half, others 3 days a week for an hour. And so on. Other important threats to reliability can come from questions or instructions that are misunderstood by students and non-course related vocabulary words that are known to some students and not to others.

Of course, then, these threats to reliability also influence the validity of course exams. There are some reasons to be a bit more optimistic about the validity of these exams, however. The content validity of course exams is often very high. Instructors are often very careful about indicating what skills and knowledge are important to learn during the course. They subsequently do a good job of ensuring that these skills and knowledge are included on their exams. If some of the threats to validity that result from reliability problems could be addressed, then we might be very optimistic indeed about the validity of course exams. Note, however, that these qualities relate only to course exams’ validity as achievement tests. Their usefulness for predicting some future performance (hence, their predictive validity) is usually an open question.

The Properties of Standardized Tests

Now, what about standardized tests (so-called aptitude tests), such as the SAT and ACT? As you might guess, standardization tends to be very good. The administration procedures are usually precisely controlled, making them quite uniform. The comparison group (standardization group) is usually very large and quite recent.

Reliability tends to be high for standardized tests, in part because of the good control of administration procedures. For example, although some people do score differently if they take the test a second or third time, most people will have very similar scores from one time to another.

Validity, however, is a more complex and controversial issue. Let us focus on the predictive validity of college aptitude tests (SAT and ACT) to illustrate the issues. As supporters of aptitude tests are quick to point out, these tests are the best single predictor of success in a wide variety of areas. This may not be true, however. Recent research conducted by the College Board, the publisher of the SAT found that high school GPA is a better predictor of college grades than the SAT is (Wingert, 2008). Still, if you ask us to pick someone who will succeed as a salesperson, a doctor, or a marketing manager, and tell us that we can know only one piece of information about that person, we might ask for the SAT score. Unfortunately, some people confuse the idea that “aptitude tests are the best single predictor” with “aptitude tests are better than all other predictors combined.” These are very different ideas. College aptitude tests (SAT and ACT) are said to be moderately successful at predicting a person’s college GPA during the first semester of freshman year. No other predictor (e.g., high school GPA, letters of recommendation) has as high a correlation with first-semester freshman year college GPA.

This does not mean, however, that the SAT predicts most of college GPA, or even that it does a great job of predicting GPA during the first semester of freshman year. Only 25% of the variability in students’ first semester freshman year GPA is related to their college aptitude test scores (Willingham et al., 1990; Wingert, 2008). Thus test scores are not a trivial tool for predicting success when a person first starts college, but at the same time, they are not infallible. With 75% of first-year freshman-year college GPA unrelated to test scores, you will find many cases of people who score high on the tests yet fail when they get to college. Similarly, community colleges across the United States have many students with SAT or ACT scores that predicted they would fail at a four-year college who end up doing extremely well and even go on to complete a bachelor’s or master’s degree or more.

Debrief

- Please try to recall some bad experiences with exams (both course exams and standardized tests). Try to assess the degree to which the bad experience was related to standardization, reliability, and validity.

- What would you do to increase the reliability and validity of course exams?

- What would you do to increase the validity of tests like the SAT or ACT?

8.2 Measuring “Intelligence”

Activate

- What is your definition of intelligence?

- How closely is intelligence, as you define it, related to success in life?

One way to begin to think about what intelligence is to examine the tests that are supposed to measure it. Let us look briefly at one of the most popular intelligence tests, the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. The WAIS-IV (for 4th edition), which was published in 2008, is described as a test of intellectual ability. The test is administered to individual test takers by a trained examiner; it takes 60 – 90 minutes to complete. It contains 10 core subtests and 5 supplemental, unscored subtests. The scored subtests contribute to an overall intelligence test score.

WAIS-IV Sub-tests

Sub-tests preceded by an asterisk are unscored subsections.

| Sub-Test | Brief Description |

| General Information | General knowledge questions |

| Similarities | Questions about how two different concepts are alike |

| Arithmetic Reasoning | Word problems involving arithmetic only |

| Vocabulary | Words and their meanings |

| *Comprehension | Understanding reasons for facts |

| Digit Span | Repeating a sequence of numbers |

| *Picture Completion | Recognizing what is missing from a picture |

| *Figure Weights | Selecting figures that “balance” a scale |

| Block Design | Rearranging blocks to match a design |

| Visual Puzzles | Choosing pieces from a set that could form a jigsaw puzzle |

| Coding | Transcribing a digit-symbol code using a key |

| Matrix Reasoning | Looking at a shape and naming or pointing to a correct response |

| *Cancellation | Scanning arrays and marking target shapes |

| *Letter-Number Sequencing | Re-ordering letters and numbers in ascending or alphabetical order |

| Symbol Search | Indicating whether a target symbol appears in a search group |

So, now you know roughly what a typical test of intelligence looks like. (You might also think about the college entrance exams you may have taken; although they are not supposed to be intelligence tests, they are based on principles designed to measure intelligence; Gardner 1999). But could you now describe exactly what intelligence is? No one really has a good, complete definition of intelligence with which everyone will agree. Furthermore, as you might have noticed from the WAIS description, intelligence tests do not measure the types of abilities that most people, including many psychologists, would count as intelligence. That is one reason why the subject of measuring intelligence has become rather controversial.

Many would agree that standardized intelligence-type tests mostly measure your ability to solve problems in very specific areas, namely math and language. Scores on these tests have been shown to modestly predict success in other areas as well, such as on the job (at least for certain jobs). Some psychologists have argued, however, that these other types of success depend much more on abilities—what we might call non-academic intelligences—that are beyond skills in using math and language.

The most complete current theory that describes the structure and organization of the cognitive abilities that we would call intelligence is the Cattell-Horn-Carroll (CHC) theory (Flanagan & Dixon, 2014). CHC theory divides cognitive ability into three separate levels; these levels go from broad, general abilities to narrow, more specific ones. The top-level corresponds to general intelligence, the broadest level. An intermediate level includes 16 somewhat narrower, but still quite general abilities such as processing speed, reasoning ability, memory, acquired knowledge, etc. Then, there are more than 70 narrow abilities, such as:

- inductive reasoning,

- quantitative reasoning,

- communication ability,

- mechanical knowledge,

- reading comprehension,

- memory span (number of items you can hold in working memory),

- ability to remember meaningful information,

- ability to remember unrelated information,

- olfactory memory (memory for different odors),

- multi-limb coordination,

- and so on.

Think of the three levels as a hierarchy; some of the 70 narrow abilities map onto abilities in the intermediate level, which then combine to map onto the general intelligence level. Because the narrow abilities can be measured more easily, psychologists can use these both for the insights they provide about the narrow abilities themselves and for an estimation of an individual’s abilities on the higher levels.

One final observation about the theory: Note the number of abilities we just reported. CHC theory has 16 semi-general abilities and 70 narrow abilities. The ones we listed were just some interesting examples of those abilities. In other words, the theory is huge. And maybe that is a good thing. Given the rich diversity of human cognitive abilities, and the very many ways that one might exhibit intelligence, it makes sense that it would take a monster-sized theory to describe it. CHC theory has been very useful at guiding and organizing research, and it undergoes frequent revision as new research comes in. We hope that sounds familiar and good, as this is exactly what a theory is supposed to do (see Module 2).

Successful Intelligence

Robert Sternberg took a slightly different track in the development of his theory of intelligence. He noted that traditional views of intelligence tended to include only problem-solving in an academic context and ignored the set of abilities that truly allow people to succeed in life. Sternberg calls his concept Successful Intelligence. It encompasses the abilities of recognizing and maximizing strengths, recognizing and compensating for weaknesses, and adapting to, shaping, and selecting environments. Sternberg defines three important components of successful intelligence (Sternberg and Grigorenko, 2000; Sternberg, 1996):

- Analytical intelligence: The conscious direction of mental process to solve problems. It involves identifying problems, allocating resources, representing and organizing information, formulating strategies, monitoring strategies, and evaluating solutions. The “intelligence” tested by many traditional tests of intellectual ability compose a small portion of analytical intelligence only.

- Creative intelligence: Generating ideas that are novel and valuable. It often involves making connections between things that other people do not see.

- Practical intelligence: An ability to function well in the world. It involves knowing what is necessary to do to thrive in an environment and doing it. Because our world is essentially a social one, interpersonal and communication skills are keys to practical intelligence.

These three component intelligences combine to determine a person’s successful intelligence. Interestingly, Sternberg believes that successful intelligence can be improved.

A Final Word on Different Views of Intelligences

Which one of these views on intelligences is correct? This is, perhaps, not a fair question. Because intelligence is defined differently by different psychologists, both views may be considered correct. It seems very likely that a set of abilities related to managing emotions and understanding and dealing with people (including oneself) is a key component for success in life. And these abilities, more than any others, are the keys to success that are not tested by traditional intelligence tests and other intellectual aptitude tests.

Cattell-Horn-Carroll Theory of Cognitive Ability: A comprehensive theory of human cognitive ability that organizes intelligence in three levels, from the highest general intelligence level, through intermediate broad abilities, and to more than 70 narrow abilities.

Successful intelligence: Robert Sternberg’s characterization of intelligence as three separate abilities that allow an individual to succeed in the world.

Are tests unfair?

Of course, tests can be unpleasant experiences for some people. Many unpleasant experiences are fair and beneficial, however. For example, many people do not particularly like injections, but they endure them because they know that the shots are good for them. So, it is not enough to condemn testing because the experience is difficult and unpleasant. We need to take a good look at whether they treat people fairly. One exercise you may find helpful in that regard is to take a quick glance backward, to the history of intelligence, intelligence testing, and aptitude testing.

As you might know, intelligence and intelligence testing have been quite controversial over the years. Perhaps the topic was doomed to controversy from the very beginning. In the late 1800s, one of the pioneers in the area, Francis Galton, promoted the view that intelligence was entirely hereditary. He also believed that various races differed in their intelligence and took it as a given that men were more intelligent than women. Most controversially, perhaps, it was Galton who developed the concept of eugenics, a field that sought to encourage the reproduction of “genetically superior” people and discourage the reproduction of “genetically inferior” people (Hunt, 2007).

Although Galton developed his own tests of intelligence, they tended to focus on sensory abilities (this was another of his beliefs, that these sensory abilities were related to intelligence) and were not particularly influential in the fledgling field of intelligence testing. Intelligence testing as we know it really began with Alfred Binet and Theodore Simon in France at the beginning of the 20th century. Binet and Simon created a test designed to predict which children would succeed and which ones would have difficulty in school. Binet and Simon conceptualized the idea of mental age, the cognitive abilities that should correspond to a particular age. Later, the concept would be given a number, the famous IQ, or intelligence quotient. IQ is the ratio of mental age to actual age (multiplied by 100). A child with the same mental and actual age, therefore, has an IQ of 100. A child with a mental age of 10 and an actual age of 8 would have an IQ of 125 (10/8 = 1.25). Intelligence testing quickly developed into aptitude testing, testing designed to predict future performance. The practice was embraced in the US and was adopted by the US military to classify recruits during World War I.

Fresh from its perceived success in the war effort, the testing world evolved in the 1930s to create a new controversy. In 1926, the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) was developed to admit students to Ivy League universities (a small group of east coast, extremely elite schools, such as Harvard and Yale). The original intention was to create a test that could discover students who would be able to excel at these institutions despite not having had the advantage of an east coast college-preparatory education. That is, the goal was to tap into a student’s potential, a potential distinct from one’s educational experience (Lemann, 1999). Unfortunately, it did not quite work out that way. The SAT and its chief competitor, the ACT, ended up largely “discovering” students from the very same advantaged backgrounds that they had sought to move beyond (Gardner, 1999). So, an important piece of the history of aptitude tests is that the individuals who had better educational experiences, particularly wealthy whites, performed better on the tests.

What does it mean for a test to be unfair? Many students might initially argue that it is essentially the same thing as being difficult, but that is not quite right. A test can be difficult and fair. As an aside, it is important to distinguish between the fairness of a test and the fairness of using the test. A test may be perfectly fair, but if it is used for an unintended purpose, it will be unfair. For example, some personality tests that have not been designed to predict success on the job have been used for job selection purposes.

In order for a test to be fair, it should be acceptably high on the test construction principles, standardization, reliability, and validity. Second, it should be unbiased, meaning that it should treat everyone the same. These ideas apply to both aptitude tests and course exams, by the way. We have already described the issues surrounding standardization, reliability, and validity, so let us focus on the question of bias.

In many cases, whether a test is biased or unbiased is a legal question. For example, think about job selection procedures. (sec 20.1) According to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, a department of the US Government, a selection procedure, including a test, is suspect if it results in a hiring rate for minority group members below 80% of the rate for the most-hired group. At that point, it is up to the employer to prove that the selection procedure is valid. So, in principle, it can be acceptable for a test to be biased against a group, as long as it does a good job at predicting success. In reality, however, it can be very difficult to justify the use of a biased test unless the validity is extraordinarily high.

As a result of the attention that psychometricians have paid to bias over the years, the most obvious sources of biases are gone from the widely used tests. They are probably not all gone, however. For example, some researchers note that the SAT is still biased against African Americans, Asian Americans, and members of the Latinx community (Freedle, 2003).

Let us finish this discussion of the fairness of tests by turning to a common complaint about course exams that sounds like a matter of content validity. Some students believe that an exam was unfair because they spent time studying a topic that ended up not being on the test. Although this could be a weakness of content validity (the test failing to sample from the appropriate skills and knowledge), it is more likely a misunderstanding of how course exams are supposed to work. When instructors give an exam, they would like to be able to conclude that students’ performance on it reflects their mastery of all of the associated course material, not simply the material on the exam.

The way this works is that the process of giving an exam is analogous to the process of conducting a survey with a representative sample. Survey researchers draw random samples from a population in order to generalize from a small sample to the whole population (sec 2.2). As long as each individual member of the population has an equal chance of being included in the sample, the researcher can conclude that the results of the sample reflect the opinions of the whole population. Course exams work the same way. Instructors’ “population” is all of the material from the course. They want to be able to determine whether you have learned everything. Of course, one way to do that would be to test you on everything, but that would result in a test that is as long as the material you have learned. So, your instructor samples from the material. If you are able to correctly answer questions on a sample of material—as long as you do not know exactly what that sample will be prior to the exam—your instructor can assume that you could have correctly answered questions from any possible sample of material. In other words, we can assume that you learned all of the material by testing you on a relatively small portion of it.

Debrief

- Did your earlier definition of intelligence contain any of the “non-intellectual” abilities described in this section?

- Can you think of an example of how the wording of an aptitude test question could be biased?

8.3 Test Anxiety

Activate

Think about the most important test you can remember taking.

- How nervous were you during the test?

- How long before the test did you start getting nervous?

- Did your nerves cause you to do better or worse on the test than you would have had you been completely calm?

Some students seem to shine on tests. The pressure of needing to do well enhances their memory and performance. Others, however, are not so fortunate. Despite studying, in many cases, longer than the “shiners,” these students find themselves blanking out on tests, nearly paralyzed by an anxiety that makes them forget much of what they studied. Why does the stress of taking a test translate into increased performance for some and debilitating anxiety (and reduced performance) for others? In order to answer this question, it is helpful to understand how stress affects memory.

Stress, as Module 27 describes more completely, arouses the body. It is important to realize that the body does not differentiate between psychological threats, such as exams and deadlines, and physical threats, such as being held up at gunpoint. These environmental threats or challenges are called stressors. For both psychological and physical stressors, the physiological reactions that take place have collectively been called the “fight or flight” response. Essentially, stressors cause the body to prepare itself to meet a physical danger—even when the stressor is psychological—by giving it a temporary boost in its ability to fight or run away from the danger. So, your heart beats faster in order to pump blood, which sends glucose (sugar, for energy) and oxygen throughout the body faster. This blood is diverted from parts of the body not needed to face the danger, such as the digestive system, and pumped to the large muscles of the arms and legs (so you can fight or run). This is why your stomach gets jumpy and your mouth gets dry when you are under stress.

Another part of the body that gets a boost of energy is the brain, particularly the areas that are involved in memory formation. Stress hormones also affect the memory-related areas of the brain. The result is a boost in memory during stressful events, which helps explain the “I do my best testing under pressure” folks.

But what about those who suffer from test anxiety? The key observation that is missing so far is that the memory-boosting effects of stress result from short-term, mild to moderate stressors only. Long-term, severe stressors have the opposite effect, they make memory worse.

How short is short-term? After about 30 minutes of a constant stressor, the brain’s use of glucose for extra energy returns to its regular level (Sapolsky, 2004). Beyond 30 minutes, there is actually a rebound effect, a reduction in the brain’s use of glucose. The student who begins to get nervous for a 1:00 exam at 12:55 is not much affected by this rebound effect. It is not so good, though, for the student who wakes up at 7:00 am already anxious about the exam.

To make matters worse for the test-anxious student, the very same event will be more threatening, and thus more stressful, for some students than others. Think about it. If you have had a lot of success taking exams in the past, each new exam is likely to seem fairly unthreatening. On the other hand, if you frequently do poorly on exams, each new exam is very threatening. The result is that the same mid-term exam or the same college aptitude test will be a short-term, mild to moderate stressor for some students and a longer-term, severe stressor for others. The students who fall in the latter group suffer from test anxiety.

The trick for the test-anxious, then, is to turn exams and standardized tests into short-term, mild-to-moderate stressors. Easier said than done, you say. The very activity that is intended to prepare you for the exam, studying, becomes stressful itself as you begin to think about the likelihood of failure. The key is to continue to prepare, studying as hard as or harder than you have been, but with two important differences. First, pay very close attention to the information in Module 7 about metacognition. It will be very helpful for you to develop the ability to reflect on your thinking and studying, so you will have a very accurate estimate of just how prepared you really are. Second, and perhaps more importantly, you should learn how to relax when you begin to feel anxious while studying. Remember, the ideal is to become a little anxious right before the exam begins, so if you are feeling anxiety at any time before then, you should probably engage in some calming or relaxation behaviors. You should develop a repertoire of relaxation techniques, some short and simple, others longer and more involved. Depending on what the situation allows and how anxious you are feeling, you can then choose from among several alternatives.

Here are a couple of techniques to help you begin to learn how to relax in the face of test anxiety (from Davis, Robbins Eshelman, and McKay, 1995). One is very short and simple, the second a bit more involved.

- STOP Technique. Whenever you find yourself getting anxious about a test (while studying or taking the test), silently “shout” to yourself to “STOP!” Once you have distracted yourself from the anxiety-provoking thoughts (which may take several “shouts”), start paying attention to your breathing. Take slow, deep breaths, making sure that your abdomen moves out with each inhalation. Count your breaths. Inhale. Exhale and count one. Inhale. Exhale and count two. When you reach 4, start over with one. Try to concentrate on the breaths. Don’t worry if you find yourself thinking the anxious thoughts again. Just “STOP” yourself and continue counting your breaths. Continue until you feel relaxed. You can repeat the procedure any time you start thinking anxious thoughts.

- Progressive Relaxation. Begin in a comfortable position, either sitting or lying down. Clench your right fist tightly, paying close attention to the tension in your fist and forearm. Relax and pay attention to the difference in feeling. Repeat once more with the right fist, then twice with the left. Bend your elbows and tense both biceps. Again, pay attention to the tension. Relax and straighten your arms, paying attention to the different feeling. Repeat once. Repeat the procedure twice with different areas of the head and face, for example, forehead, jaws, eyes, tongue, and lips. Tense your neck by tucking your chin back. Feel the tension in different areas of the neck and throat as you slowly move it from side-to-side and let your chin touch your chest. Relax and return your head to a comfortable position. Tense your shoulders by shrugging them. Relax them and drop them back. Feel the relaxation in your neck, throat, and shoulders. Relax your whole body. Take a deep breath and hold it. You will feel some tension. Exhale and relax again. Repeat several times. Then, tighten your stomach. Relax. Breathe deeply, letting your stomach rise with each inhalation. Note the tension as you hold each breath and the relaxation as you exhale. Tense and then relax your buttocks, thighs, calves, and shins (tense your calves by pointing your toes, shins by pulling your toes toward your shins) twice each. As you relax, notice how heavy your whole body feels. Let the relaxation go deeper, as you feel heavy and loose through your whole body.

You should practice these techniques for a week or two when you are not feeling anxious so that they will be easier to use when facing the real thing.

Debrief

- In general, do you think that you need to increase or decrease your level of anxiety to achieve your best performance on tests?

- If you need to increase your anxiety, what strategies do you think you can use to help you?

- If you need to decrease anxiety, which of the strategies presented in this section seem most useful to you? Can you think of other useful strategies?