10 Module 10: Biology and Psychology

The discovery that at least some mental disorders have biological causes led to what has been called the era of biological psychiatry (Seligman, 1993). The key scientific development was Richard von Krafft-Ebing’s proof that a common form of madness, known through the centuries as general paresis, was actually caused by syphilis, a physical illness. Krafft-Ebing was able to make his discovery despite the fact that researchers had not yet developed techniques to see the germ that causes syphilis. Instead, he reasoned that because syphilis could not be caught twice, anyone suffering from general paresis must be immune to syphilis. When he exposed paresis patients to syphilis and none of them contracted the disease, Krafft-Ebing had his proof (Seligman, 1993).

According to Martin Seligman (1993), adherents to biological psychiatry believe that mental illness is actually a physical illness, which can only be cured by drugs. Further, they believe that personality, being genetically determined, is fixed. The idea that we cannot change that which is biological about ourselves, at least without pharmacological intervention, is a very sweeping and, to us, pessimistic conclusion.

Fortunately, that conclusion is far too simple to be correct, and it is rejected by most researchers in biopsychology (as opposed to adherents to what Seligman called biological psychiatry). As Modules 11, 29, and 30 reveal, sometimes a drug treatment is an important, even necessary, component of a cure for a psychological disorder. It is rarely a sufficient treatment by itself, however, and many disorders can be treated with no drugs at all.

This module gives you the background to judge why the broad conclusions of biological psychiatry are oversimplified. For example, it is true that a great deal of our behavior and mental processes have genetic causes. That does not mean that genes are the only causes, however, and it does not mean that they are unchangeable.

The module is divided into two sections. Section 10.1 describes the basics about genes and heredity. It is essential background information if you want to be able to understand many claims about genetics. The section also introduces you to behavior genetics, the subfield that allows you to estimate the degree to which a given trait is determined by genes, and the important developments in epigenetics. Section 10.2 introduces you to evolutionary psychology, a relatively new, important, and controversial perspective in psychology that tries to place what we know about genetics and psychology into the context of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution by selection.

- 10.1 Genes and Behavior

- 10.2 Evolutionary Psychology

READING WITH A PURPOSE

Remember and Understand

By reading and studying Module 10, you should be able to remember and describe:

- Basic concepts of heredity: genes, DNA, chromosomes (10.1)

- Dominant and recessive genes (10.1)

- Genotype and phenotype (10.1)

- Interaction between genes and environment (10.1)

- Basic ideas and research methods of behavior genetics: heritability, twin studies, adoption studies (10.1)

- Theory of natural selection (10.2)

- Evolutionary psychology: natural selection, sexual selection (10.2)

Apply

By reading and thinking about how the concepts in Module 10 apply to real life, you should be able to:

- Make a reasonable prediction of the relative heritabilities of some common traits (10.2)

Analyze, Evaluate, and Create

By reading and thinking about Module 10, participating in classroom activities, and completing out-of-class assignments, you should be able to:

- Compare your prior beliefs about nature and nurture to the textbook material on genetics, behavior genetics, and evolutionary psychology (10.1 and 10.2)

- Support your position in favor or against the basic claims of evolutionary psychology (10.2)

- Generate a possible evolutionary explanation for specific human traits and behaviors (10.2)

10.1. Genes and Behavior

Activate

- In what ways are you similar to your closest blood relatives? In what ways are you dissimilar?

- Do you believe that similarities and differences between people’s personalities and other psychological tendencies result more from genetic factors or environmental factors?

- Jot down anything you can remember about genetics from a biology class you have taken.

In the introduction to this module, We raised the possibility that there are things about yourself that you cannot change. Although the idea that psychological tendencies are fixed is wrong, there definitely are some unchangeables. You cannot change your parents, and you cannot change the genes, the coded information you inherited from them. There is a genetic contribution to just about any psychological phenomenon, trait, or behavioral tendency that you can think of. As we have said, however, that does not mean that you are automatically doomed to suffer (or blessed to enjoy) the consequences of your genes.

On the other hand, you simply cannot ignore the role of heredity in psychology. In addition to helping you understand many important psychological phenomena, knowledge of the principles of heredity will certainly help you to understand yourself. A solid working knowledge of these concepts will help you make sense out of the large (and increasing) amount of information about genetics (and psychology) in the popular media.

Genetics

You should be aware of two important roles for genes. As you may already know, genes are the basic unit of heredity, the biological transmission of traits from parents to offspring. They do more than just determine the color of your eyes or how tall you will be, though. They also determine many psychological tendencies, which is why we care about them in psychology. What you may not have realized is that genes continue to work throughout our lives. Although many people think that genes finish their work as soon as we are born, they actually are responsible for the building of all the cells in our bodies throughout our lives. You have perhaps heard that proteins are the building blocks of our body. Did you ever wonder where the proteins come from? They are synthesized, or built from their component ingredients, by cells that have been programmed by genes. Although in psychology we concern ourselves principally with genes’ role in heredity, it is important to keep this other function in mind, too.

How genes determine traits.

In 2003, a team of researchers completed a map of the human genome, the complete set of all human genes, a project that began in 1990. Many casual observers believed that this impressive scientific feat would explain many human behaviors and mental processes. For example, they may have believed that somewhere in the genome we would find a gene for depression, another for happiness, another for aggression, and so on. The truth, however, is nowhere near that simple. At best, in the vast majority of cases, a particular gene might mean a predisposition, an increased likelihood that some psychological trait would be present. Further complicating matters is the fact that some genes actually have functions other than determining some trait. These genes act to turn on or off other genes, which in turn might produce the suspected predisposition only when other genes are also present and active.

As you might guess, the possible combinations are essentially limitless. Furthermore, a given behavior or trait might very well appear in many different ways. For example, consider Alzheimer’s disease, a very serious disorder that leads to profound memory loss. A few cases of Alzheimer’s strike as early as 40 years old. Three separate genes have been linked with many of these early-onset Alzheimer’s cases (Goate et al., 1991; Sherrington et al., 1995; Levy et al., 1995). Over 99% of Alzheimer’s cases begin after age 60, however. Two different genes have been linked with late-onset Alzheimer’s, and together they are related to only about 40% of the cases (Bertram et al., 2000; Stritmatter & Roses, 1995). As you might guess from this short description, Alzheimer’s disease is quite complex, and researchers are still trying to figure out what causes it; you will learn more about their progress in Module 16.

The fact that a given condition may be associated with several possible genes may help us to understand many puzzles. For example, we know that antidepressants are effective for only about half of the people who take them, but we do not know why. Perhaps there are different types of depression, with different physiological mechanisms because they result from the actions and interactions of different genes.

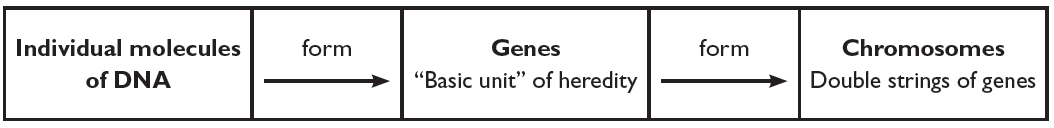

In order to understand genes’ role in heredity, it is important to know some details about how they are organized. Although genes are often considered the basic unit of heredity, they can themselves be subdivided into their components. Genes are made up of molecules of deoxyribonucleic acid, commonly called DNA. Nucleic acids, such as DNA, are the only kind of molecules in nature that can direct their own replication (Campbell & Reece, 2002). DNA contains all of our hereditary information, which can be reproduced and passed down to our offspring.

Genes themselves are organized into chromosomes. A chromosome is basically a doubled string of genes. Every species has a specific number of chromosomes; humans have 23. When sperm and egg meet during fertilization, each contributes one strand of 22 chromosomes (the 23rd is a little different, as we will describe in a moment). So you inherited half of your DNA from your mother and half from your father. On each chromosome, you have strings of paired genes, approximately 34,000 genes total. Every cell in the body contains a complete copy of your 23 chromosomes; thus, every cell has all of your particular genetic material.

Figure 10.1: DNA, Genes, and Chromosomes

Figure 10.1: DNA, Genes, and Chromosomes

One pair of chromosomes is special, the sex chromosomes. They determine your sex, along with some additional traits. There are two kinds sex chromosomes, X and Y. The X chromosome is much larger than the Y; in addition to information about your sex, it contains genes for other characteristics, such as colorblindness, that are not on the Y chromosome. The mother always contributes one X. The father may contribute an X or a Y. If the father contributes an X, the baby will be a girl; if he contributes a Y, the baby will be a boy.

heredity: the biological transmission of traits from parents to offspring

genome: the complete set of all genes in a species

genes: the basic unit of material that gets transmitted from parents to offspring

DNA: deoxyribonucleic acid; these are the molecules that make up genes

chromosomes: a doubled string of genes; each species has a specific number of chromosomes

sex chromosomes: the chromosomes that determine your sex; there are two types, X and Y

This description of genetic heredity is rather simplified. The genes that go into each egg and each sperm may get scrambled a little bit through a process called crossing over, so the half-chromosomes you inherit from your parents are not identical to the ones they themselves have. In other words, you are not an exact genetic copy of half of each parent. Rather, you inherit large sections of DNA, along with some modified sections from the crossing over process.

In the simplest cases of trait transmission, a single pair of genes inherited from both parents determine a trait. For example, one version of the gene for eye color causes brown eyes, and another causes blue eyes. If you inherit the brown version from both mother and father, you will have brown eyes. Likewise, if you inherit the blue version from both, you will have blue eyes.

What if you inherit a brown version from one parent and a blue version from the other? Usually, one version dominates the other; it is called the dominant gene, and the other is called the recessive gene. In the case of eye color, brown is dominant. This means that if you have a brown version from one parent and a blue from the other, you will have brown eyes.

Because there are two ways that you can have brown eyes (brown-blue genes or brown-brown genes), biologists must distinguish between what they refer to as the genotype, the particular combination of genes, brown-blue or brown-brown in this case, and the phenotype, the physical trait exhibited, brown eyes. The distinction between genotype and phenotype helps to explain why some children with brown-eyed parents have blue eyes. If both parents have the brown-blue genotype, any of their children could end up with a genotype for eye color consisting of one blue-eyed gene from the mother and one blue-eyed gene from the father.

Now, keep in mind that eye color is controlled by a single set of genes. Psychological tendencies, such as shyness or irritability, are typically far more complex than this. There are many traits controlled by more than two versions of a gene or by two genes or more, and no interesting psychological tendencies have been traced to a single gene. Even in these more complicated cases, however, the relationship between dominant and recessive genes usually holds.

dominant gene: the gene version that codes the trait that the offspring will inherit when the parents contribute different versions

recessive gene: the gene version that codes the trait that the offspring will not inherit when the parents contribute different versions

genotype: the genetic coding that underlies a specific observed trait

phenotype: an observed trait, which might result from different specific gene version combinations

It’s not Nature versus Nurture, It’s Nature and Nurture

You may recall that in Module 4, we told you about one of the key historical philosophical debates that made it into the field of scientific psychology, namely, nature versus nurture. Are we a product of our genes (nature) or our experiences, upbringing, and environment (nurture)? You probably realized that even without us telling you that this really is a false dichotomy, a kind of oversimplification (see Module 1). It is not really one or the other. It is a combination of both. That is a pretty unsatisfying answer, however, kind of like just splitting the difference. It is indeed a bit more correct to note that personality, intelligence, mental illness, etc. are a result of genes and environment. But only a bit more correct. Seriously, now that you know this, do you really feel as if you understand the relative roles of genes and environment in psychology? We thought not (we assume you said, “No.”). So, let’s talk about 3 key ideas that really do help us to understand what we mean by “it’s nature and nurture.”

Behavior Genetics

There is a subfield of psychology that tries to sort out the nature-nurture puzzle by estimating the contribution of genes and environment for a given trait; it is called behavior genetics. Behavior geneticists come up with numerical estimates of the relative contributions of nature and nurture. For example, they have determined that the genetic contribution to intelligence is in the 50% – 75% range. These percentages are known as the heritability of some trait, which is defined as the percentage of trait variation in a group that is accounted for by genetic variation.

Notice in this definition that heritability is a conclusion about a group, not an individual. So, it does not mean that 50% – 75% of your intelligence comes from your genes, the rest from your environment. Rather, it means that if you give an intelligence test to a group of people, 50% – 75% of the differences in the scores can be attributed to differences in the group members’ genes. The main reason this is important is because the group you are examining can change; when it does, so too can your estimate of heritability. For example, suppose you administered your intelligence test to a group of children at a single elementary school in a wealthy suburb of Chicago. It is easy to imagine that the children at this school might very well have similar environments, most of them coming from stable two-parent homes, with similar economic backgrounds and educational experiences in and out of school. In this case, precisely because the children’s environments are so similar, a great deal of variation in intelligence test scores would have to be attributed to genetic variation (simply because there is not enough environmental variation). On the other hand, suppose your group of children included students from a privileged background and students from a very poor neighborhood in the city of Chicago. The differences in environments are enormous. The genetic contribution to differences in this group’s intelligence test scores would be overwhelmed by the differences in between the environments. In the first, suburb-only case, estimated heritability of intelligence would be high, closer to 75%; in the second case, it would be low, closer to 50% (or lower). Thus, the second important observation about heritability is that it is not a fixed number; it depends on the actual differences in the environment that are present for a group. This also means that when you hear about stable estimates of heritability, that the numbers are averages based on many individual studies involving many thousands of people.

The two most important methods that behavior geneticists use for estimating heritability are twin studies and adoption studies. In twin studies, identical twins, fraternal twins, and non-twin siblings are compared to each other. Identical twins are natural-born clones; they are identical genetic copies of each other. Fraternal twins are genetically no more similar than non-twin siblings, each sharing on average half of their genes. In a twin study, the three groups could be given a survey of life satisfaction, for example. If life satisfaction is heritable at all, the correlation between scores for the identical twins will be higher than that for the fraternal twins and non-twin siblings. The size of the difference in correlations between the groups can be used to come up with the estimate of heritability.

Adoption studies examine the other side of the coin. They look more directly at the contribution of the environment among people who do not share genes. Two children born to different parents adopted into the same family can be compared to examine the influence of shared environment on the traits in question.

A somewhat glib summary of the conclusions of the behavior geneticists is that everything is heritable. Steven Pinker (2002) notes, however, that this statement is only a slight exaggeration. Pinker’s partial list of psychological traits and conditions that have a significant genetic component includes autism, dyslexia, language delay, learning disability, left-handedness, depression, bipolar disorder, sexual orientation, verbal ability, mathematical ability, general intelligence, degree of life satisfaction, introversion, neuroticism, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. We will have several opportunities to examine the link between genetics and these and other phenomena throughout the book. But keep in mind that “significant genetic component” does not mean 100%. In fact, most estimates of heritability for different psychological traits and conditions hover around or below 50%. In most cases, you are not trapped by your genes, even though they play an important role in shaping human behavior. And this brings us to the second key idea.

- adoption studies: a method in behavior genetics in which children with different biological parents but the same adopted family are compared in order to assess the impact of a shared environment

- behavior genetics: the psychological subfield that estimates the contribution of genes and environment for specific psychological tendencies and traits

- heritability: the proportion of variability in a trait throughout a group that is related to genetic differences in the group

- twin studies: a method in behavior genetics in which identical twins, fraternal twins, and non-twin siblings are compared in order to assess the heritability of a trait

Gene x Environment interaction.

Further complicating matters—or as we prefer to think about it, making matters more interesting—are questions about how genes and environment combine. Basically, genes and environment interact. Let’s take a simplified example to illustrate some of the issues involved. Suppose researchers discovered a single gene for aggression (extremely unlikely at this point). Imagine that you, as someone with that aggressive gene, are placed into an environment in which no one ever makes you angry. It is possible that you might never become aggressive. Perhaps you can begin to see why you are not a slave to your genes.

You can also access this video directly at: https://youtu.be/QxTMbIxEj-E

(In a classic episode of The Twilight Zone, a town lives in fear of a young boy who punishes people with his tele-kinetic powers whenever anyone makes him angry. The townspeople spend their days making sure the boy never gets angry, a failed attempt to create the environment we just suggested. If you need a fun 5-minute break, watch the clip above.)

The best way to think about the role of genes in the development of psychological traits is that the genes may create a predisposition, a tendency to possess a particular trait. In order for the trait to be realized, however, the person must be exposed to a certain environment. For a more realistic example, Terrie Moffitt and Avshalom Caspi are frequent contributors to the research literature on gene x environment interactions. In one study of over 2,000 children, they found that those who had been bullied were more likely to develop emotional problems, but only if they possessed one specific variant of a gene that is related to regulation of serotonin concentration (a neurotransmitter implicated in mood, see Module 11).

Epigenetics

And finally, the third, and perhaps most interesting, key idea to help us understand the complexities of nature and nurture. Perhaps you had already learned about the distinction between genotype and phenotype in an earlier biology class, so you were familiar with dominant and recessive genes and their role in getting from genotype to phenotype. In this section, we will describe a second essential factor in producing phenotype. This factor is epigenetics, one of the key developments in genetics over the past 40 years. Epigenetics refers to changes in gene expression that are not related to the contents of the genes themselves (i.e., changes in the DNA) (Weaver, 2020). In other words, they change the activity of DNA without changing the DNA itself (Lester et al., 2016).

To understand these definitions, you need to know what we mean by gene expression or gene activity. The basic concept is relatively simple. Genes provide the instructions for the body to produce proteins. A gene might be present in a particular cell of the body, but it only provides those instructions when it is expressed. Think of it as turning on the gene so that it can perform its work (producing a protein). These proteins then go on and do x, y, and z.

Chemicals called tags can become attached to small portions of DNA and can influence the expression of the genes (increasing or suppressing it). This collection of tags is called the epigenome. So the importance of epigenetics is that there are substances within the epigenome that can increase and others that can suppress the expression of genes, but they don’t do anything to permanently change those genes. The key idea that places this in the nature and nurture context is that research, mostly on rats and mice, suggests that the epigenome can be affected by the environment. For example, Weaver et al. (2004) showed that rat pups’ epigenome changed as a result of mothers’ licking and grooming behaviors.

Researchers have recently begun to apply epigenetics to human behavior, that is, psychology (Lester, Conradt, & Marsit, 2016). Three key psychological areas in which researchers have applied epigenetics are development and mental health (and regular stuff?)

For example, Koopman-Verhoeff et al. (2020) found that epigenetic mechanisms are associated with certain types of sleep problems in children. On the other side of the lifespan, Pivsha et al. (2020) discovered the role of epigenetic mechanisms in psychotic symptoms that affect some sufferers of Alzheimer’s disease.

All of this is interesting and reveals some important context to the idea of a gene x environment interaction. If you were not already familiar with epigenetics, though, we predict that the next point will amaze you. The epigenome can be transmitted across generations. In other words, suppose diet affects your epigenome (this is very likely true, by the way; see Hullar & Fu, 2015). The tags that get attached to your DNA—that is, the epigenetic changes—change the way your own genes express proteins, as we have described. But these same epigenetic changes might be transmitted to your children when they are born. How is that for pressure? Junk food is not just bad for you; it might also be bad for children you might have in the future.

Debrief

- Which psychological traits or tendencies do you think would have the largest genetic component (i.e., highest heritability)? Which would have the smallest?

- What do you think would be the relative heritability of such well-known psychological tendencies as happiness, anxiety, depression, intelligence, and extraversion?

8.2. Evolutionary Psychology

Activate

- Do you believe in Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection (evolution)?

- In your opinion, what is the main objection that people have to the concept of evolution?

- Why might some people who believe in evolution in general object to its application to psychology?

Although evolution is one of the most important discoveries in the history of science, it has often been accompanied by controversy. Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, which introduced the basic theory, generated an explosive public reaction. Today, criticisms of evolutionary psychology have gone so far as to include insults about the researchers’ sex lives (Pinker, 2002). Although this is not the place for a full discussion of evolution and the controversy surrounding it, a short treatment of the issues is in order.

The Controversy over Evolution

When people refer to evolution, they are referring to Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection or one of the modern versions of it. Darwin formulated the theory of natural selection after a long journey through the South America region as a young man in the early 1830s. During the voyage, he observed and collected many fossils and samples of plants and animals. He was struck by how similar South American samples were to each other and how different they were from European samples with which he was familiar. At the same time, he was reading about the then-new idea that the earth was very old and changing. Upon his return, Darwin began to realize that species must have changed over time in response to their environment—in short, that species evolve. He proposed the theory of natural selection in 1859 to explain how evolution occurs.

Natural selection means that traits that allow an organism to survive are more likely to be passed down from parents to offspring. The reason is simple; the beneficial traits are more likely to keep the organism alive long enough to reproduce. Over time (usually very long periods of time), as more and more of the organisms with the beneficial traits reproduce, and fewer and fewer of those without them do, species evolve to have only the beneficial traits. These beneficial traits are known as adaptive traits.

Even back then, Darwin had an enormous amount of supporting evidence, and evolution was accepted by most biologists very quickly (Campbell & Reece, 2002). The public, however, especially in the United States, resisted the theory. Even today, most adults in the US do not believe in evolution. For example, a recent survey found that 40% of US adults believe humans were created in our present form in the last 10,000 years (Gallup, 2019). On the other hand, there is an overwhelming consensus among scientists in favor of evolution (Pew Research Center, 2020). They note that evolution is supported by an enormous body of evidence, so much evidence that the theory has attained the status of fact (Futuyma, 1995). David Buss (2007) points out that there has never been a scientific observation that has falsified the basic process of evolution by selection.

Many non-scientists do not believe in evolution because it contradicts their belief in the literal interpretation of the Judeo-Christian Bible. Although this is not the place for a full discussion of this controversial issue, there is one important fact to keep in mind. Belief in evolution can co-exist with belief in the Bible. In 1950, for example, Pope Pius XXII stated that “there was no opposition between evolution and the doctrine of the faith about man and his vocation, on condition that one did not lose sight of several indisputable points.” In 1996, Pope John Paul II agreed. Granted, both popes did dispute some important facets of particular theories of evolution, but they had seen the scientific evidence in favor of evolution and understood that it is overwhelming.

- natural selection: the key concept in Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution; traits that helped an individual to survive are more likely to be passed from parent to offspring and become more common in future generations

- adaptive traits: specific traits that help an individual to survive

The Controversy over Evolutionary Psychology

With this brief background in evolution, we can now move on to evolutionary psychology.

Of course, a public that does not accept evolution, in general, is not likely to put much stock in evolutionary psychology. The controversy runs deeper, however, as even many psychologists are not persuaded by many of the claims of evolutionary psychologists. Let us briefly examine the issues. Throughout the later modules in the book, we will have opportunities to revisit and amplify these issues as they relate to specific claims about people.

The goal of evolutionary psychology is to understand the human mind/brain from an evolutionary perspective (Buss, 2007). It is concerned with how the current form of the mind was shaped; what the components of the mind are, how they are organized, and what they are designed to do; and how the environment interacts with the mind to lead to behavior. There are two ways to apply evolution to psychology, corresponding to two mechanisms originally outlined by Darwin. The first is natural selection as described above, through which traits end up common in humans because they helped our ancestors to survive long enough to reproduce. The second is sexual selection, through which traits are selected in a species because they helped our ancestors win a mate (Buss, 2003).

Psychologists have had little trouble accepting the first application, natural selection. For example, in order for our human ancestors to survive long enough to reproduce, they had to be able to escape from predators. Those that were able to find a boost of energy and strength during such times of danger were able to successfully fight or flee from the predator. Thus, we have evolved a stress response commonly known as the “fight or flight response,” that increases our heart rate and blood pressure, and diverts blood flow from body systems not needed to face the danger, such as digestion, and sends it to the large muscles of the arms and legs.

Sexual selection, however, has not been as safe from controversy among psychologists. The types of strategies suggested by sexual selection involve competition within genders and preferences in mating partners, which are ideas that have met with a great deal of resistance. For example, evolutionary psychologists have noted that men across the world tend to prefer women whose physical appearance signals fertility, such as youthfulness and a low waist-to-hip size ratio (that is, waist significantly smaller than hips). These women, the evolutionary explanation goes, were assumed to be more likely to become impregnated, which would allow the man to reproduce. Observations like these reinforce sexist stereotypes and consequently, have been met with a great deal of resistance from some psychologists.

From a psychologist’s perspective, the problem with these descriptions of natural selection and sexual selection so far is that we have not described a scientific approach to understanding human behavior and mental processes. Rather, an evolutionary psychology fashioned this way is simply telling stories about how some human traits came to be; some critics of evolutionary psychology have called them “just-so stories,” named after the fanciful tales by Rudyard Kipling that told how the elephant got its long trunk, for example (it was stretched by a crocodile). To be a bit more precise, the critics assert that evolutionary psychology does not generate useful scientific theories because they can seemingly explain any possible phenomenon. For example, one might be able come up with an evolutionary explanation for why women would prefer men who signaled fertility. The critics feel that evolutionary psychology is too “after the fact,” or post hoc.

Supporters claim that a careful examination of the methods of evolutionary psychology reveals that this criticism may be somewhat off base, however. To be sure, evolutionary psychologists sometimes seem to work in reverse of the typical “use theory to generate hypotheses and make observations” order. Rather, they find some interesting observation and generate a hypothesis or theory to explain it. If the evolutionary psychologists stopped there, the critics would have a valid criticism. They do not stop, however. Instead, now armed with a new theory, they go on to generate novel predictions. Further, they do so by using multiple types of data collection strategies, such as comparing different species; comparing genders within a species; and examining historical, anthropological, or paleontological evidence (Buss, 2007). But the debate continues. Philosopher Subrena Smith (2019) has tried to unravel the entire field of evolutionary psychology by noting that it is impossible to know if present-day cognitive mechanisms were actually adaptive in the past because no one really knows what the true environmental pressures were in the past. Absent that knowledge, we would at least need a “fossilized” version of an ancient human brain, something else that does not exist. She refers to this as the matching problem, and contends that it makes evolutionary psychology unscientific (not being concerned with actual empirical observations). As a result, she claims that evolutionary psychology is impossible, and the early response to her thesis has stirred up strong opinions on both sides of the debate (Mind Matters, 2020).

It is difficult to completely deny that evolution plays a role in human psychology. After all, evolution is the unifying theme of all of biology. Humans are every bit biological organisms as the members of any other species are, and our brains are not exempt from the processes that affect all other animals’ brains. One problem is that part of the controversy seems to stem from some of the specific explanations that come from evolutionary psychology and with some of the non-scientific ideologies associated with the application of evolution to humans.

Throughout the theory’s history, people supposedly following the principles of Darwinian natural selection have initiated (and followed through on) some heinous activities. For example, the eugenics movement of the early 20th century was essentially an attempt to selectively breed humans—that is, to impose selection pressures on people (Hunt, 1993). The most horrific institution of a eugenics-like policy in modern times was the “final solution” of the Nazi-led Holocaust, Hitler’s attempt to create a genetically pure Aryan master race. Another, less dramatic, perversion of Darwinian principles were known as social Darwinism. According to social Darwinism, people who were economically worse off were so because they were genetically less fit. Herbert Spencer, an early proponent of this view, believed that to help the less well off could conflict with the process of evolution and ultimately hurt humanity. Steven Pinker (2002) notes, however, that the social Darwinists were confusing economic success with reproductive success; social Darwinism simply does not follow from the theory of natural selection. The history of the misuse of evolutionary theory makes many observers nervous about any application of the theory to people.

The concept of sexual selection also has some serious political baggage connected to it. For example, evolutionary psychology reframes phenomena such as conflict, aggression, sexual jealousy, and deception as adaptive solutions to problems of survival and reproduction faced by our ancestors. For example, sexual jealousy may have evolved as an adaptive solution to the problem of uncertain paternity (Dal et al., 1982). Quite simply, a male can never be completely certain that the baby born to his mate is his. Therefore, ancient males who had a strategy to prevent female infidelity—that is, males exhibiting sexual jealousy—were more effective at impregnating their mates and producing offspring. Further, one of the key strategies of dealing with sexual jealousy may have been to assault one’s mate, to ensure that she did not stray. This is an alarming prospect that something like spousal abuse is explained by saying that the behavior was an adaptive solution to an ancient reproductive problem.

Evolutionary psychologists are sometimes seen as apologists for social ills, such as spousal abuse, gender and racial inequality, and male violence. Leaping to the defense of evolutionary psychology, Pinker’s (2002) simple observation is that we can and should have a system of values and morality that is independent of our biological predispositions. For example, evolutionary psychology suggests that men and women have key psychological differences. If our society deems discrimination against a gender wrong, however, it should be irrelevant whether women on average tend to experience basic emotions (not including anger) more intensely than men. David Buss (2003), a prominent evolutionary psychologist, argues that the fact that humans may have antisocial psychological tendencies that arose because of our ancestral past does not excuse this behavior in modern people. In fact, he notes, by acknowledging antisocial tendencies, we stand a better chance of solving social ills.

The jury is still out on many of these questions; we just do not know whether particular evolutionary explanations of human behavior are correct or not. It would be a tragedy if the fear of ideological contamination prevented the research from being done, however, especially if the evolutionary psychologists are correct. On the other hand, we must continue to be vigilant about the misuse of evolutionary principles to drive an unfair or dangerous agenda, and we must insist that proponents of a new subfield adhere to the highest scientific principles (see Module 14 for another take on this debate).

- evolutionary psychology: the subfield of psychology that focuses on understanding the human mind/brain from an evolutionary perspective

- sexual selection: the process through which specific traits are passed on from parents to offspring because they helped an individual win a mate

- eugenics: a misuse of evolutionary principles that attempted to selectively breed humans to remove “unwanted” traits from humanity

- social Darwinism: a misapplication of evolutionary principles that proposed that people who were worse off economically were so because they were evolutionarily less fit

- stress response: commonly known as the “fight or flight response.” The physiological response that results in increased heart rate and blood pressure, diverted blood flow from body systems not needed to face the danger, and increased blood flow to the large muscles of the arms and legs.

Debrief

- Try to come up with an evolutionary explanation for: Male and female sexual infidelity, sadness, anger, anxiety, happiness