6 Module 6: Learning and Conditioning

Many students are confused when they first encounter the concept “learning” in their psychology class. We all know what learning means, having been students for at least 12 years prior to taking a college General Psychology course. Every day, we are asked, encouraged, or forced to “learn” new material in classes. Then you encounter a chapter in a General Psychology textbook called Learning, and it talks about a child who comes to fear a white rat because it is paired with a loud noise or a pigeon that pecks on a surface in order to receive a pellet of food. There seems to be some disconnect here between your experience of learning and what psychologists want to tell you about learning.

But there isn’t really a disconnect. The common thread is this idea: behavior (and knowledge) can change as a result of experience. When it happens, we call it learning. This is an intentionally broad definition. It encompasses both of the phenomena mentioned earlier—a child learning to fear a rat and a pigeon learning to peck—plus all that you are likely to have in mind when you think of learning.

As you read this module, keep in mind that the learning with which you are most familiar, the kind that takes place in a school setting, involves remembering information in order for you to prove that you learned it (for example, for you to perform well on an exam). Thus, it is often useful for you to think of learning and memory as parts of the same process. How can you remember something if you did not learn it? And how can you say that you have learned something if you do not remember it?

This module describes several basic types of learning, but it focuses primarily on two. The first is classical conditioning, in which the learner comes to associate two events in the environment, called stimuli. The second is operant conditioning, in which the learner comes to associate a behavior with its consequences. Together, classical and operant conditioning are sometimes called associative learning, because both involve learning some association, or link. The last section in the module concludes with a description of some other phenomena that also qualify as types of learning.

- 6.1 Learning That Events Are Linked: Classical Conditioning

- 6.2 Learning That Actions Have Consequences: Operant Conditioning

- 6.3 Other views of learning

associative learning: learning based on making a connection between two events in the environment, or stimuli (classical conditioning), or between behavior and its consequences (operant conditioning)

learning: changing knowledge and behavior as a result of experience

READING WITH PURPOSE

Remember and Understand

By reading and studying Module 6, you should be able to remember and describe:

- Learning (psychologist’s definition) (6 introduction)

- Basic elements of classical conditioning: unconditioned stimulus, unconditioned response, conditioned stimulus, conditioned response (6.1)

- Higher-order conditioning (6.1)

- Generalization and discrimination (6.1)

- Extinction and spontaneous recovery (6.1)

- Basic elements of operant conditioning: positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, positive punishment, negative punishment (6.2)

- Shaping (6.2)

- Continuous and partial reinforcement (6.2)

- Immediate and delayed consequences (6.2)

- Side effects of punishment (6.2)

- Primary and secondary reinforcers (6.2)

- Observational learning, non-associative learning, habituation, sensitization (6.3)

Apply

By reading and thinking about how the concepts in Module 6 apply to real life, you should be able to:

- Recognize and explain examples of classical conditioning (6.1)

- Recognize and explain examples of operant conditioning (6.2)

- Recognize and explain examples of observational learning (6.3)

- Recognize and explain examples of non-associative learning (6.3)

Analyze, Evaluate, and Create

By reading and thinking about Module 5, participating in classroom activities, and completing out-of-class assignments, you should be able to:

- Explain why some bad habit in yourself or others has developed using principles from the module (6.1, 6.2, 6.3)

- Devise a strategy for studying that uses principles from the module (6.1, 6.2, 6.3)

6.1 Learning That Events Are Linked: Classical Conditioning

Activate

- Have you ever developed an aversion to a food because of a bad experience with it? What happened?

- Have you ever developed a fear of some object or situation because of a bad experience? What happened?

- Do you generally eat meals at the same time every day? If so, what happens if you miss a regularly scheduled meal?

Ed is a 55-year-old former Military Police officer. He has complained that he cannot drink beer because, as an MP, he often had to break up fights at bars. Even today, decades after his duty, he finds that the smell of beer gets him too worked up.

Ciara is a dog who seems to be able to read her owner’s mind. She seems to know that her owner is going to take her running as soon as he decides to do it.

Although it may not be obvious at first, these two descriptions are both examples of the same psychological phenomenon, classical conditioning. Classical conditioning is learning that two stimuli are associated with each other. A stimulus is simply an event or occurrence that takes place in the environment and leads to a response, or a reaction, in an individual. For example, suppose that you are fortunate enough to have someone feed you dinner every night. Further, suppose that this kind person does this at the same time every night, 6:00 pm. On the first day, you look up at the clock and see that it is 6:00 (a stimulus), and your benefactor makes dinner appear in front of you (another stimulus). Second day, same thing: 6:00, and dinner appears. It will not take you too many days to learn that these two stimuli are associated- every time the clock says 6:00, someone gives you dinner. This is the essence of classical conditioning, and it explains a wide variety of animal and human behavior.

Think carefully for a moment about how we could tell that someone has learned to associate the time on the clock with dinner. Consider the second part of the definition of a stimulus; it leads to a response. One way see if someone has learned that two stimuli are associated would be to observe how he or she responds to the two. If we discover that the person responds to the clock the same way that she responds to dinner, it is reasonable to conclude that she has learned the association between the clock and dinner. Specifically, when you begin to eat dinner, your body responds in very specific ways—for example, salivation begins, the stomach begins to secrete acids, the pancreas begins to secrete insulin, and so on. To keep things simple, focus on the salivation response for a moment. If the person begins to salivate when the clock says 6:00 pm, even when dinner is not served, we can tell that she has learned to associate the two stimuli.

And precisely what association is learned? As psychologists have observed, it is that one stimulus predicts that the other stimulus is about to occur. So, the 6:00 clock face predicts that dinner is about to occur, or the smell of beer for a military police officer predicts that he will soon encounter a fight that he will have to break up.

The mechanisms of classical conditioning were originally spelled out in the early 1900’s by the Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov. A bit later, classical conditioning was embraced by a group of psychologists known as the behaviorists. John B. Watson, the most famous and influential of the behaviorists, believed that the principles developed by Pavlov could explain all of human behavior. Classical conditioning does do a good job of explaining some very interesting aspects of human (and animal) behavior, although it falls short, of being a complete explanation of human psychology (see Module 9).

classical conditioning: a type of associative learning, in which two stimuli are associated, or linked, with each other

response: a reaction to something that takes place in the environment (a stimulus)

stimulus: an event or occurrence that takes place in the environment and leads to a response in an individual

How Two Events Become Linked: Stimulus and Response

With these basic ideas in mind, we can take a closer look at the details of classical conditioning. As you begin to learn the distinctions among some important terms—what are known as the unconditioned stimulus, unconditioned response, conditioned stimulus, and conditioned response—try to avoid the temptation to memorize through repetition. Rather, recode to make these concepts meaningful (see Module 5). Two key questions will help you in this regard:

- Are you considering something that originated in the environment, or is it a person’s (or animal’s) reaction to something in the environment? If it originated in the environment, it is a stimulus. If it is a reaction to the stimulus originating in the person (or animal), it is a response.

- Are you looking at a relationship between a stimulus and response that is automatic (unlearned), or did the person (or animal) have to learn it? Conditioned means learned, so the answer to this question will tell you whether you are looking at a stimulus and response pairing that is unconditioned or conditioned. Specifically, automatic stimulus-response pairings are called unconditioned, and learned pairings are called conditioned.

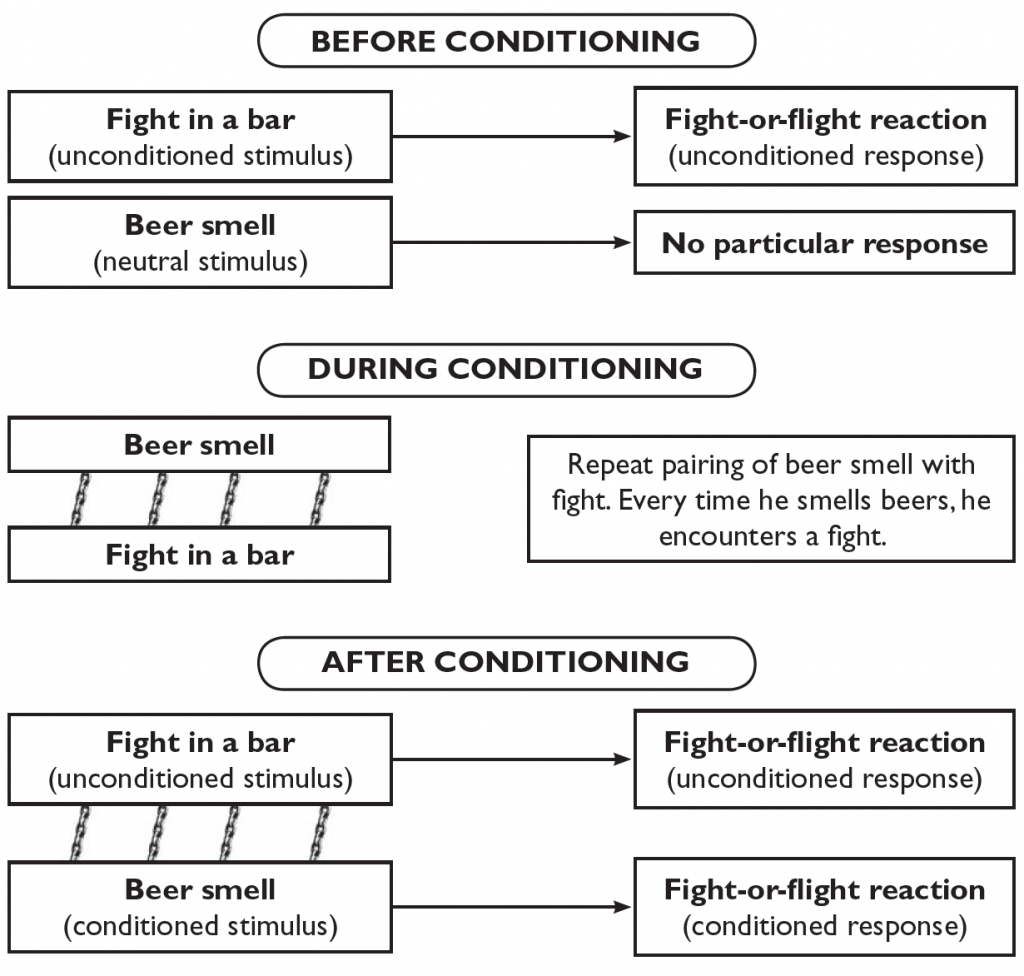

Let’s apply these two questions to a specific classical conditioning example. Before Ed became a Military Police officer, the smell of beer probably had very little effect on him. Being called upon to break up a fight, however, does lead to the automatic, and very dramatic, “fight-or-flight” response. For instance, the heart will begin to race, and the digestive system will shut down as blood is diverted from it to the body systems that will allow the person to face the physical danger, principally the respiratory system, circulatory system, and the large skeletal muscles of the arms and legs (see Modules 11 and 28).

The two questions, in this case, are easy to answer:

- The part that originated in the environment is the fight (the stimulus), and the physiological changes that Ed experiences are what the person does in reaction to the stimulus (the response).

- The fight-or-flight response is automatic, that is, unlearned, so we are observing an unconditioned stimulus (UCS) and an unconditioned response (UCR).

Classical conditioning occurs when the unconditioned stimulus is paired with something else that originates in the environment (another stimulus), in this case, the smell of beer. Originally, this stimulus had no particular power to produce a response. In other words, it was a neutral stimulus. Over the course of his experience as an MP officer, though, every time Ed smelled beer, he found himself confronted with a fight to break up. After a few pairings of beer with fight, Ed began to have a fight-or-flight response when he smelled beer alone. This new response was learned, or conditioned, so it is called the conditioned response (CR). The stimulus that elicited it, the smell of beer, is called the conditioned stimulus (CS).

The smell of beer used to be neutral for Ed, but because of the pairing with the bar fights, he learned to associate the two stimuli. Thus, he has been classically conditioned. Again, what he has learned is that the smell of beer—the conditioned stimulus—predicts that a fight—the unconditioned stimulus—is about to occur.

In real life, it is not always so easy to decide whether something is a stimulus or response. A stimulus may occur because of something you did, so it might seem like a response. For example, Ed might open a beer bottle to produce the smell of beer. But that beer smell itself comes from the environment and leads to a response, so it is a stimulus. Similarly, suppose you are the person who feeds yourself at 6:00 every night. Although you prepare the dinner, the food comes from the environment and leads to a response in you (the digestive response). Therefore, it is a stimulus.

Also, it can be challenging to tell the difference between conditioned and unconditioned. If you are having difficulty, consider this observation. The unconditioned stimulus is ALWAYS the unconditioned stimulus. A bar fight leads to the fight-or-flight response the first time, fifth time, tenth time, and thousandth time it happens. It does not change. The conditioned stimulus changes. At first (before conditioning), it is neutral. It leads to nothing interesting. It is only after repeated pairing of this stimulus with the unconditioned stimulus that it begins to lead to response. In other words, it does change. It goes from being a neutral stimulus to a conditioned stimulus.

One other realization might help you keep the distinction between conditioned and unconditioned straight. Think again about what, precisely, is being learned. The individual comes to realize that some formerly meaningless stimulus (smell of beer, clock saying 6:00, etc.) has begun to predict that something important is about to occur.

conditioned response (CR): In classical conditioning, an organism’s learned response to a conditioned stimulus

conditioned stimulus (CS): In classical conditioning, an environmental event that an organism associates with an unconditioned stimulus; the conditioned stimulus begins to lead to a reaction that is similar to an unconditioned response.

neutral stimulus: In classical conditioning, an environmental event that does not lead to any particular response related to the conditioning situation. This stimulus will become a conditioned stimulus.

unconditioned response (UCR): In classical conditioning, an organism’s automatic (unlearned) reaction to an unconditioned stimulus

unconditioned stimulus (UCS): In classical conditioning, the environmental event that leads to an automatic (unlearned) response

Higher-order conditioning

All right. Now suppose you have a very strongly learned conditioned stimulus. As an MP officer, you are unlucky enough to be called on to break up hundreds of fights, each with its corresponding beer smell. In cases like this, the conditioned stimulus can become so well established that it can eventually become an unconditioned stimulus in a future round of classical conditioning. This type of conditioning is called higher-order conditioning. Again, think of it as a “later round” of conditioning. A conditioned stimulus in round one that is very well established becomes the automatic, or unconditioned, stimulus in round two. Higher-order conditioning can then repeat several times until it is difficult to identify the original conditioned stimulus.

For example, consider the dog, Ciara, we mentioned in the beginning of the section. She has always loved going running with her owner. This stimulus, being taken running, leads to an automatic response: she gets excited. Thus, these are unconditioned stimulus and unconditioned response. Over time, a neutral stimulus, namely a leash, gets paired with the unconditioned stimulus (every time the owner gets the leash, Ciara gets taken running). Thus, the leash becomes a conditioned stimulus that causes Ciara to get excited (conditioned response). Round 1 is over.

Now, begin conditioning round 2. Because the leash had become a strong conditioned stimulus at the end of round 1, it will become an unconditioned stimulus in round 2. A new neutral stimulus, namely the owner putting on running shoes, now gets paired with the new unconditioned stimulus (every time they put on their running shoes, they get the leash). At the end of round 2, putting on running shoes is a conditioned stimulus that will cause Ciara to get excited.

The conditioning can continue to round 3. A new neutral stimulus, the owner going into the closet to get the shoes, gets paired with the new unconditioned stimulus (the conditioned stimulus from round 2, putting on the shoes). And so on. By the end of several rounds, Ciara has undergone 4th, 5th, or even 6th order conditioning, as she learns to associate new stimuli with previously learned stimuli.

How Conditioned Responses May Change with Time and Experience

A few more details will help you to recognize and understand the many examples of classical conditioning that you may encounter. The period during which classical conditioning occurs is called acquisition. During acquisition, in order for conditioning to occur, the conditioned stimulus must come before the unconditioned stimulus. If you recall the earlier point about prediction, it is easy to see why this is so. In order for the conditioned stimulus to be a good predictor of the unconditioned stimulus, it must come first. A predictor that occurs after, or at the same time as, the event it is supposed to predict is not very useful.

Imagine that you were once bitten by a big yellow dog named Rex. You might easily develop a fear of Rex through classical conditioning. But many people who have an experience like this go on to fear other dogs as well, even little white or black or brown ones; in some cases, they may come to fear all dogs. What has happened is that stimulus generalization has taken place. Stimulus generalization occurs whenever a conditioned response occurs in the presence of stimuli that are similar to the original conditioned stimulus. On the other hand, what if you have a dog? In this case, although you might still develop a fear of Rex and some other dogs, it is likely that you would not come to fear your own dog. In this case, stimulus discrimination has occurred. Stimulus discrimination is when a conditioned response does not occur in the presence of a stimulus similar to the original conditioned stimulus.

Classical conditioning effects do not last forever; they fade over time. If a conditioned stimulus is presented repeatedly without pairing it with the unconditioned stimulus, the conditioned response will grow weaker and eventually disappear. This is called extinction. For example, suppose Rex bites you, and then you adopt a new puppy. At first, because of generalization, you may have a classically conditioned fear of the new puppy. Over time, however, as this puppy (a conditioned stimulus) is presented to you without the unconditioned stimulus—she does not bite you—your fear may fade.

The concept of extinction is perhaps misnamed, however, because the conditioned response is not really dead. After a delay, it will reappear in a weakened from, a process called spontaneous recovery.

acquisition: the period during which classical conditioning occurs

extinction: in classical conditioning, the fading away of a conditioned response after repeated presentation of a conditioned stimulus without the unconditioned stimulus

spontaneous recovery: in classical conditioning, the reappearance of a formerly extinct conditioned response after a delay

stimulus discrimination: in classical conditioning, a situation in which an organism learns to not have a conditioned response in the presence of stimuli similar to the original conditioned stimulus

stimulus generalization: in classical conditioning, a situation in which an organism has a conditioned response in the presence of stimuli similar to the original conditioned stimulus

How Understanding Classical Conditioning Can Help You

You may now feel that you can recognize some examples of classical conditioning in your life. It may not be obvious, however, that you can use this knowledge to help you. The thing for you to realize is that many typical conditioned responses—good and bad habits, if you will—are classically conditioned.

For example, many people have a bad habit of falling asleep when they study, particularly if they try to study in bed. Perhaps now you can see this habit as classical conditioning. The comfortable stimulus of your bed may be an unconditioned stimulus that leads to an unconditioned response of drowsiness. If you frequently read your chemistry textbook in bed, the textbook will become a conditioned stimulus that will also make you feel drowsy (even later when you do not read it in bed). Stimulus generalization may also occur, and then you might discover that any textbook (except psychology, of course) makes you feel drowsy.

Other habits, such as being anxious or being unable to study in certain situations, may likewise be examples of classical conditioning. The trick is for you to recognize them as such and use the principles you learned in this section to break the habits. Stop pairing the conditioned stimulus with the unconditioned stimulus (for example, stop reading in bed) to encourage extinction to occur.

Better yet, you might try to make your chemistry book a conditioned stimulus for a more productive conditioned response, such as studying and being alert. This concept, called counterconditioning, replaces an original conditioned response with a new, incompatible conditioned response; it is the basis for a common therapy that psychologists use to treat phobias (see Module 30).

Debrief

- If you were able to answer “yes” to any of the questions in the Activate exercise, describe your experiences as examples of classical conditioning, being sure to label the unconditioned stimulus, unconditioned response, conditioned stimulus, and conditioned response.

- If you did not generate any examples in the Activate exercise, describe a new example of a time when you learned the association between two stimuli. Again, be sure you can label the UCS, UCR, CS, and CR.

6.2 Learning That Actions Have Consequences: Operant Conditioning

Activate

- Describe a behavior or activity that you do because you have been rewarded for it in the past.

- Describe a behavior or activity that you used to do, but do not do any longer because you were punished for it.

Suppose you decide to study for an upcoming exam by using recoding for meaning and retrieval practice with the spacing effect. When you get your exam score, you find that you got the highest grade you have ever received. Assuming you find this consequence pleasant, you will be more likely in the future to study using the same techniques. On the other hand, suppose you insult your psychology professor by pointing out that his clothes look funny. On your next written assignment, you get the lowest grade you have ever received. Assuming this consequence is unpleasant, you are rather unlikely to insult your professor again in the future. This, in a nutshell, is operant conditioning.

Understanding Different Kinds of Consequences

In order to understand operant conditioning well, you have to learn to distinguish between the two different types of consequences, known as reinforcement and punishment. As you read the descriptions, take time to understand them and be careful; these concepts are among the most misunderstood in all of psychology.

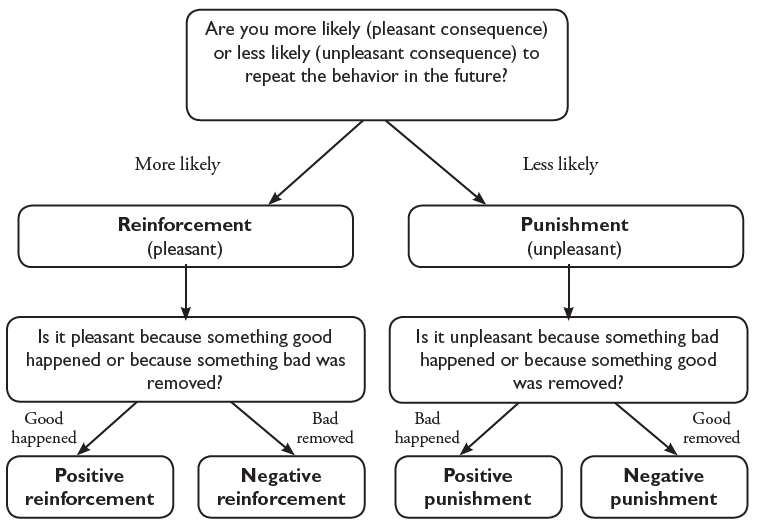

Let’s start abstractly, with the general ideas. Again, pleasant consequences make it more likely that you will repeat a behavior in the future, and unpleasant consequences make it less likely that you will repeat a behavior in the future. Consequences that make it more likely that you will repeat a behavior are called reinforcements, whereas consequences that make it less likely that you will repeat a behavior are called punishments.

There is already a complication that makes it difficult to recognize the difference between reinforcement and punishment. Basically, there are two main ways that we could do something pleasant to you: we can give you something good, or we can take away something bad. Similarly, there are two ways that we could do something unpleasant to you: We can give you something bad, or we can take away something good. These four possibilities constitute the four main types of consequences that are important in operant conditioning; they are called positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, positive punishment, and negative punishment. This diagram shows how you can decide which type of consequence is creating the learning:

Note that the terms “positive” and “negative” have nothing whatsoever to do with whether the consequence is pleasant or unpleasant. They refer only to whether something was done to you (positive) or taken away from you (negative).

Another reason that many students find it difficult to recognize examples of punishment is that they believe that someone must be doing the punishing. This misconception is consistent with the common usage of the English word punishment—as, for example, when we talk about parents punishing their children. It does not matter where the consequence comes from, however. If the consequence is unpleasant and you are less likely to repeat the behavior in the future, it is punishment.

Let us summarize and recap with an example of each of the four types of consequences:

- Your decision to study using the Module 5 techniques in the future because of the good grade you received on an exam is an example of positive reinforcement. The pleasant consequence occurred because something good (the high grade) happened to you. You are likely to repeat the behavior again—that is what makes the consequence a reinforcement.

- Imagine that you are plagued by anxiety whenever you do not study hard enough for an exam. Every time you do study, you find that the anxiety goes away. You are likely to find this consequence (getting rid of the anxiety) pleasant. Therefore, you are likely to increase your studying, so this consequence is a reinforcement for your behavior. Because the reinforcement occurred by taking away something bad (the anxiety), it is negative reinforcement.

- The example of insulting your psychology professor is positive punishment. The consequence, getting a low grade, will make you unlikely to insult your professor again, which makes it a punishment. And getting a low grade is something bad that happened to you, not a good thing that was removed.

- Losing driving privileges as a consequence of committing traffic violations is an example of negative punishment. A driver who has their license suspended becomes less likely to commit the violations in the future. Thus, because the unpleasant consequence occurs by taking away something good (the right to drive), it is negative punishment.

One additional distinction that you should know is between primary and secondary reinforcers. A primary reinforcer gains its power to increase behavior because it satisfies some biological need. The clearest examples are food and water. A secondary reinforcer gains its power to increase behavior through learning. In short, you learn that a secondary reinforcer is valuable; hence, it is perceived as rewarding. Perhaps the best example of a secondary reinforcer is money. Both primary and secondary reinforcers can be quite effective at increasing behaviors.

negative punishment: in operant conditioning, punishment that occurs because of the removal of something good

negative reinforcement: in operant conditioning, reinforcement that occurs because of the removal of something bad

positive punishment: in operant conditioning, punishment that occurs because of the addition of something bad

positive reinforcement: in operant conditioning, reinforcement that occurs because of the addition of something good (i.e.that is, a reward)

primary reinforcer: a reinforcer that meets some biological need

punishment: in operant conditioning, a consequence of behavior that makes it less likely that the organism will repeat the behavior in the future

reinforcement: in operant conditioning, a consequence of behavior that makes it more likely that the organism will repeat the behavior in the future

secondary reinforcer: a reinforcer that has the power to increase behavior because the organism learns that it is valuable

Why Reinforcement Works Better Than Punishment

You have perhaps noticed something missing in the earlier examples of positive and negative punishment. Consider the insulting the psychology professor scenario. Although you may stop the face-to-face insults if you received a low grade on your assignment, would you then go around thinking and saying only good things about your professor? Probably not. On the contrary, you would likely be very angry and might engage in some other behavior that the professor might find objectionable (for example, complaining to the department head, or leaving a bad review on Ratemyprofessor.com). An important fact to realize about punishment is that, although it may decrease the likelihood of a specific behavior, it does not necessarily replace that behavior with a more appropriate one.

Because punishment only tells you what not to do and not what to do, many psychologists favor the use of reinforcement when trying to influence the behavior of others. Parents, for example, are advised to use punishment sparingly, because it might be followed by some other unwanted behavior. To be sure, when it is necessary to stop a dangerous behavior quickly, punishment may be the only practical means available. A parent should always keep in mind, however, that the child needs to be shown what to do after being shown what not to do. Finally, note that punishment does not refer to physical punishment( e.g., corporal punishment), which is rarely recommended by psychologists (see Module 17).

How Time Affects the Link Between Behavior and Consequence

It is not only the pleasantness or unpleasantness of a consequence that determines its influence on subsequent behavior. Two additional important factors are the amount of time that passes between the behavior and the consequence and the frequency of the consequence.

The amount of time between behavior and consequence has a very strong influence on how effective operant conditioning will be. Immediate consequences are much more effective than delayed consequences. For example, some people find it difficult to take advantage of the delayed positive reinforcement that results from working hard, such as good grades in school or recognition at work. Instead, their behavior is more likely to be influenced by the immediate consequences of goofing off, such as having fun.

As for the frequency of the consequence, suppose someone starts giving you $10 every time you answer a question during class discussions, even if you are wrong. How long do you think it would take you to start answering every question? Then suddenly, your benefactor stops paying you for talking. Now, how long do you think it would take for you to stop answering questions? You have just discovered the characteristics of what is known as continuous reinforcement—reinforcement that occurs every time the behavior does. You probably realized that with a schedule of continuous reinforcement you would acquire the behavior (answering questions in class) very quickly, which is exactly what is observed when continuous reinforcement is used. You probably also predicted that soon after the reinforcement stops coming, you would stop doing the behavior. Again, this is what happens with continuous reinforcement. Rapid learning and rapid extinction are the hallmarks of continuous reinforcement.

Suppose instead that you get money for speaking in class, but not every time you do it. This method of reinforcement is known as a partial reinforcement schedule. It may take you a while to begin speaking in class, but what do you think will happen when the reinforcement stops? Perhaps you figured out that extinction would be much slower with partial reinforcement than with continuous reinforcement.

For example, consider a dog that continues to beg for scraps whenever someone takes food out of the refrigerator, despite the fact that the entire family has been instructed not to give the dog people food. Many years ago, however, this behavior was reinforced on an occasional basis by a well-meaning, but uninformed relative. (“Oh, every so often won’t matter, as long as I don’t feed him every time.”) He continued begging for 10 years. You can just imagine the dog thinking, “This time, he’s going to give me the piece of cheese.”

Similar to what we saw for punishment, there is a clear parenting application to this concept. Parents who give in to their children’s tantrums only occasionally are essentially using partial reinforcement of the bad behavior. Much of the advice to parents that they must be consistent in their parenting practices relates to the pitfalls of partial reinforcement.

continuous reinforcement: reinforcement that occurs after every appearance of a behavior. It leads to rapid learning; when the reinforcement stops, extinction is rapid

partial reinforcement: reinforcement that occurs only after some appearances of a behavior. It leads to slow learning; when the reinforcement stops, extinction is slow

How Operant Conditioning and Classical Conditioning Work Together

The separate discussions of operant and classical conditioning in this book reflect the historical development of the two concepts, and make it easier to explain them. In the normal course of the day, however, operant and classical conditioning are not separate. They can work together to cause human and animal behavior.

For example, imagine that your family has a cat that has a habit of walking on the dining room table. In order to train the cat to get off the table, many people use a bottle to spray it with water. Eventually, your kitty would jump off the table as soon as you walked into the room with your spray bottle. The pairing of spray bottle (a CS) with the jet of water (a UCS) is a straightforward example of classical conditioning; your cat learns that the appearance of the spray bottle predicted that she was about to get wet. Getting hit between the eyes with a stream of water (you have to practice your aiming to achieve this) for jumping on the table is a good example of operant conditioning (specifically, positive punishment). Together, these two forms of conditioning can help kitty learn to stay off the table.

How Shaping Can Help You Change Behavior

It is probably fairly obvious how you can use the principles of operant conditioning in your own life. For example, there are clear ways to apply the ideas to change your own behavior to improve your study habits or to change your children’s behavior. You should know about one more concept to help you in case you ever decide to try these principles, however.

Imagine that you decide to use operant conditioning to increase the length of time that you can study without your mind wandering. Currently, you can make it for about five minutes before some distraction becomes so magnetic that you cannot resist leaving your desk. Your goal is to study for one hour at a time without interruption, so you decide to use positive reinforcement; you will reward yourself with one dollar in a “shopping spree” jar every time you are able to study for one hour. At the end of the month, you can spend that money on anything you want. After 30 days, you reach for your jar to discover with dismay that it is empty. You were never once able to make it to one hour without distraction.

The concept that you need to know to start filling that jar and increasing the length of time that you can study is called shaping. Shaping is teaching (or learning) a new behavior by reinforcing closer and closer approximations to the desired behavior. Rather than waiting until you manage a full hour of studying to reward yourself, you can give yourself the money every time you are able to study for 10 minutes, only 5 minutes longer than your current behavior. After you are able to consistently study for 10 minutes, you reward yourself only when you are able to study for 15 minutes, another 5-minute increase over your current study time. Over several weeks, you should be able to increase your study time to an hour straight, but it will be easy because every increase was only a small bump up from what you could already do. Shaping can be used to learn very complex behaviors; the key is keeping individual steps small.

Debrief

- The situations that you described in the Activate exercise (things that happened to you) were probably examples of positive reinforcement and positive punishment. Please think of several additional examples of operant conditioning that you have experienced so you have examples of positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, positive punishment, and negative punishment). In each case, was the reinforcement continuous or partial? Were the consequences immediate or delayed?

6.3 Some Other Types of Learning

Stop us if you have heard this one before. Mom and Dad were growing distressed that their two children, Joey, aged 9, and Zoey, aged 11, had begun to use profanity. They realized that they needed to do something fast, so they decided to use physical punishment to stop their children’s swearing. That night at dinner, Zoey says, “Pass the f***ing salt.” Dad immediately turns to Zoey and smacks her face, knocking her glass of milk onto her lap and her food to the floor. Then, he turns to Joey and demands, “Well, what do you have to say about it?” Joey looks at the mess and replies, “Well, you can bet your a** I’m not going to ask for the f***ing salt.”

For the record: we do not condone physical punishment under any circumstances (see Module 17). We just dug up this old joke to make a point about observational learning, which is learning that occurs through watching others’ behavior. Of particular importance is the observation of operant conditioning in someone else. For example, if a child observes his sister being punished for a behavior he may learn not to do it as effectively as if he were being punished himself. Also, as the joke hilariously illustrates (we assume you are still laughing at it), because punishment does not directly tell learners what they are supposed to do, is not a particularly efficient way to change people’s behavior.

Throughout the rest of this module, we have been describing different kinds of associative learning. Even observational learning involves learning that behavior is associated with consequences, just as in operant conditioning. You might be wondering if there is such a thing as non-associative learning. The answer is yes. Non-associative learning occurs when the repetition of a single stimulus leads to a change in an individual. Note, of course, that this stimulus is not linked with anything; it just occurs repeatedly. Over time, your experience, even your very perception of that stimulus might change. Allow us to explain with a couple of examples. Imagine that you visit a friend who lives near an airport for the first time. As your friend is making coffee for the two of you, an airplane flies overhead, and you practically jump out of your skin. Your friend, on the other hand, does not even react, continuing to make the coffee as if nothing has happened. You cannot believe it. “How can you even hear yourself think with that deafening noise?” you ask. “Oh, I got used to it. I barely even hear it anymore,” your friend answers. Your friend has experienced habituation, in which the repetition of the stimulus leads to a reduced reaction or perception over time. On the other hand, consider the opposite kind of non-associative learning, sensitization, in which the repetition of the stimulus causes a stronger reaction or perception over time. We like to call this the annoying-little-brother effect. Imagine that you have a little brother who has the worst habit of scraping his teeth on his fork when he takes it out of his mouth. You are absolutely convinced that he is doing it louder and louder just to annoy you. Maybe. Or maybe you have just experienced sensitization.

habituation: non-associative learning type in which the repetition of some stimulus over time leads to a reduced reaction to the stimulus

non-associative learning: learning, or change, that occurs because of the repetition of a single stimulus over time

observational learning: learning that occurs through watching others’ behavior

sensitization: non-associative learning type in which the repetition of some stimulus over time leads to a stronger reaction to the stimulus