28 Introduction to Mental Illnesses and Mood Disorders

Before beginning their first psychology class, many students have the impression that psychology consists solely of therapy for individuals who suffer from mental illness. Some students are surprised to discover that this aspect of psychology is a relatively small part of the total content of the course. On the other hand, even though clinical psychology, the understanding and treatment of mental illness or psychological disorders, is far from the only concern of psychology, it is a very important use of psychological knowledge. Many concepts from other psychological subfields contribute to our understanding of psychological disorders and their treatment. As you will see, insights about the brain and neurotransmitters, classical and operant conditioning, cognition, emotions, motivation, human development, and social psychology have all helped psychologists to understand and effectively treat psychological disorders.

Clinical psychologists spend years learning about the hundreds of psychological disorders that have been described. Obviously, we have to make choices about which disorders to cover in this book. We will cover only the disorders that are the most important to psychology in general, because of their seriousness, commonness, or both. In addition, we will cover a few disorders that have become well known because they are controversial.

This module begins by discussing some general issues about what it means to have a psychological disorder, and how psychologists decide that someone has a disorder and which disorder it is. Then, we will turn to what may be the most common category of disorders, mood disorders.

28.1 “Normal” and “abnormal”

28.2 Major depression and other mood disorders

28.3 Treatments for mood disorders

READING WITH A PURPOSE

Remember and Understand

By reading and studying Module 28, you should be able to remember and describe:

- How psychologists decide if someone has a disorder (28.1)

- Stigmas and stereotyping (28.1)

- General characteristics about DSM-5 (28.1)

- Major depressive disorder: suicide and depression (28.2)

- Bipolar I and II disorders (28.2)

- Biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors in mood disorders (28.2)

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy (28.3)

- Antidepressants (28.3)

- Other treatments for mood disorders (28.3)

Apply

By reading and thinking about how the concepts in Module 28 apply to real life, you should be able to:

- Come up with new examples of bias and stigma against sufferers of psychological disorders (28.1)

- Recognize examples of major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder (28.2)

Analyze, Evaluate, and Create

By reading and thinking about Module 28, participating in classroom activities, and completing out-of-class assignments, you should be able to:

- Identify misperceptions or negative attitudes that you might hold toward people who suffer from psychological disorders (28.1)

- Recognize and appreciate the differences between a depressed mood and major depressive disorder (28.2)

28.1. “Normal” and “Abnormal”

Activate

- What are some slang terms used to describe people who suffer from psychological disorders? Why do you think it is often still acceptable to use many of these terms?

- Who do you think decides that someone has a mental disorder? On what basis are such decisions made?

Psychological and mental disorders are more common than you might think. In 2017, 971,000,000 people around the world (12.7% of the world population) suffered from one (GBD, 2017). These disorders can be either contributing causes or consequences of a wide range of medical conditions, such as heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and HIV/AIDS. The WHO estimates that approximately 80% of worldwide sufferers receive no treatment. Because so few people worldwide have access to treatment for mental and psychological disorders—even though many effective treatments exist—one could argue that an effort to expand mental health programs might be the single most effective way to improve the overall health of the world’s population.

How Psychologists Decide That Someone Is “Abnormal”

As we are sure you are aware, there is an absolutely limitless set of possibilities for human behavior and mental processes. Consider anxiety, for example. People can range from completely calm to wildly panicked, and it is not difficult to imagine behavior at thousands of points between the two extremes. At what point do you draw the line and say everyone on this side is normal and everyone on that side is disordered? This is essentially a subjective decision (that is, one for which different observers might disagree), opening up the whole process of defining disorders to controversy from the very first moment.

Psychologists have come up with a set of criteria that can be used to make the decision more objective:

- How unusual and unexpected the behavior is. If someone is doing something that is completely out of the ordinary, it might be evidence that he or she is abnormal. As Oliver Wendell Holmes once said, “If a man is in a minority of one, we lock him up.” On the other hand, as Gandhi said, “Even if you are a minority of one, the truth is the truth.” Try to remember the Gandhi quotation when you are tempted to judge people simply because they are doing something unusual. The first thing you might look for is an indication of whether the unusual behavior is justified or expected given the situation. For example, a panic attack in the middle of a mall might be unusual, but it might be quite justified if you are an 8-year old child who has lost his parents. It might also be expected if you were the parent who was looking for the child.

- How much dysfunction and distress the behavior causes. Psychological disorders may cause dysfunction in many different areas of life, such as emotions, social relationships, work responsibilities, and patterns of thinking. For example, someone with major depressive disorder may report feeling sadness, social withdrawal, isolation, and fatigue that make them unable to work and maintain relationships. In other words, the disorder interferes with life in important ways. Clinicians focus a lot of their attention on the extent to which a person’s typical moods, behaviors, relationships, and thoughts are disrupted. This judgment is, as we noted previously, subjective. In addition, it is also relative. For example, imagine a college student that normally earns A’s in their classes. If the student is now struggling to maintain C’s in their classes, a clinician might note that they are experiencing dysfunction even though C’s are still passing grades and may be typical for other students. This dysfunction might also be distressing to the person suffering from the disorder or to those around them. For example, an individual who cannot get out of bed because of major depressive disorder would probably report being bothered by the inability to function. Again, however, we cannot use this criterion alone to make a final judgment. Some disordered behavior is characterized by a lack of distress. For example, people who suffer from antisocial personality disorder are not bothered by their aggressive and mean behaviors at all. Also, psychologists may judge that behavior is abnormal if the individual is unable to meet the demands of daily functioning, even if the behavior is not distressing.

- Whether the behavior is dangerous or damaging. As you know, many common behaviors are dangerous. For example, according to the US Surgeon General, cigarette smoking is responsible for over 480,000 deaths per year in the US alone; the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention reports that smoking will kill or disable half of all regular smokers. Smoking is undoubtedly dangerous and damaging. The behavior is not exactly unusual, however, as over 34 million adults in the US smoke cigarettes. Also, for many smokers, the behavior is only mildly distressing, if at all. On the other hand, a depressed individual who is suicidal is engaging in unusual, unexpected, distressing, and dangerous behavior and would be clearly judged disordered. Similarly, a person who has a severe attack of panic every time he even thinks about a vehicle and cannot work as a result is exhibiting unusual, unexpected, distressing, and damaging behavior.

These criteria remove a great deal of the doubt when trying to decide whether someone is “normal” or “disordered,” but they are not perfect. Remember that “unusual” is not the same as “disordered.” Keep in mind also that these criteria are considered in combination. One of them alone is probably not sufficient (unless it takes an extreme form) to justify a “disordered” label.

Stigmas

Unfortunately, assigning the label “abnormal” or “disordered” to a person brings with it a whole host of problems, commonly referred to as stigmas. The dictionary definition of stigma is a mark of disgrace or infamy or a bad or objectionable characteristic. If the stigmas were based in reality, it would be difficult to object to them. Let us pose the issue another way, though. In the language of social psychologists, people who suffer from psychological disorders are victims of stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination (Module 21). In other words, the stigmas are probably not based in reality but rather in preexisting notions about how people should be treated based on superficial information. Forming a stereotype based on incorrect information and applying the stereotype to all members equally is just as unfair to people who suffer from psychological disorders as it is to victims of racial, gender, socioeconomic, and other stereotypes.

The effects of stigmas and labels

Throughout history, psychological disorders have been misunderstood and feared, a situation that is quite conducive to the development of stereotypes. Probably the most common conception historically was that people suffering from some kind of mental disorder were possessed by evil spirits. There is evidence that in ancient times, individuals received “treatment” by having someone drill into their skull to release the evil spirits, a procedure known as trephination. In the 19th century, people suffering from psychological disorders were commonly placed in asylums, facilities that resembled prisons more than anything else. In essence, the goal was to keep the psychologically disordered away from everyone else.

A 2012 meta-analysis of nationwide representative surveys from around the world found that although the public’s knowledge about mental illness has increased a great deal since the 1950’s (the date of the first survey), the social stigma of mental illness has not declined much. The problem is that at least one key stereotyped idea about the psychologically disordered remains as strong as ever: that individuals who suffer from psychological disorders are likely to be violent. In fact, the belief in violence is even stronger in recent times than it was in the 1950s (Phelan et al. 1997; Vaughan & Hansen, 2004). Observers have noted that this deterioration may be largely a result of news reports and entertainment media (Phelan et al., 1997; Heginbotham, 1998; Angermeyer & Matschinger, 1996). Just think about all of the movies over the years that have depicted violence inflicted by people who suffer from psychological disorders, from Psycho to Silence of the Lambs to Split to The Joker. A Beautiful Mind notwithstanding, movies overwhelmingly portray psychologically disordered people as violent aggressors and homicidal maniacs.

This would not be much of a problem if it were true, but studies show that the relationship between serious psychological disorder and violence is weak (Pilgrim & Rogers, 2003). People who suffer from serious psychological disorders are only a little bit more likely to commit violent acts than the general population is. The overall risk of violence at the hands of people who suffer psychological disorders is—just as it is from members of the general population—very low (Swanson et al., 1990).

When a mentally disordered person does become violent, the cause may be failure to take prescribed medications (Swartz et al. 1998). Also, one of the most important variables that predict violence in the disordered population is substance (alcohol and drug) abuse (Pilgrim & Rogers, 2003). This is very interesting because alcohol abuse is linked with aggression in the general population as well (Module 20). A main reason that violence is (slightly) higher among the psychologically disordered population is that rates of substance abuse are higher in that group (Regier et al., 1990). Again, however, even among psychologically disordered individuals who abuse substances, most do not become violent (Steadman et al., 1990).

Even on the rare occasions that psychologically disordered individuals do turn violent, they typically attack family members or other people that they know (Eronen et al., 1998; Lindqvist & Allebeck, 1989). You are at very little risk of being the victim of a homicidal attack by a stranger with mental illness. A great deal of the stereotypes and stigma associated with psychological disorders thus stems from an unrealistic fear of violence, a fear that comes largely from the misapplication of the availability heuristic, the tendency to judge the frequency of an event by how easily instances can be brought to mind.

With that in mind, let me offer the “other side of the coin,” an alternative world in which the media choose to focus on the remarkable accomplishments of some individuals who suffer from psychological disorders, not on their potential for violence. We might have a very different view of these disorders indeed. For example, consider the following list:

| Person | Profession/Known For | Psychological Disorder |

| John Nash | Mathematician (won Nobel Prize) | Schizophrenia |

| J Balvin | Musician | Depression/Anxiety |

| Jim Carrey | Actor and Comedian | Depression |

| Abraham Lincoln | US President | Depression |

| Ernest Hemingway | Writer | Bipolar Disorder |

| Vincent Van Gogh | Artist | Bipolar Disorder |

| Emily Dickenson | Poet | Depression |

| Sylvia Plath | Writer | Depression |

| Karen Carpenter | Musician | Anorexia Nervosa |

| Virginia Woolf | Writer | Depression |

Please note: Unless an individual has made a disorder public—as in the cases of Jim Carrey and Kanye West, for example—we cannot be certain about whether someone had a disorder or not. We can be fairly confident by examining details about their lives, but it can be difficult to pinpoint which disorder a person has or had.

Another important source of misunderstanding about psychological disorders is related to the dualism-monism distinction (Module 26). Because some people believe in dualism—in other words, that the mind and body are separate—they tend to think of physical disorders and mental disorders as different kinds of disorders (although that is one specific area where knowledge has increased over the years). Saying to a mentally disordered person that something is “all in your mind” implies that the problem is imaginary, as if the mind is not real.

Concrete Effects of Stereotypes and Labels

The stigmas associated with mental illness have real-world consequences. For example, researchers found that mothers who suffer from psychological disorders are more likely to be judged unfit parents simply because of their diagnosis rather than because of the way they treat their children (Benjet, Azar, & Kuersten-Hogan, 2003). Stigmas also commonly prevent people from seeking the treatment that could help them. For example, a systematic review of 144 studies found that stigmas associated with mental illness was one of the top barriers to treatment that people who suffer from psychological disorders face (Clement et al., 2014).

Diagnosing Disorders: The DSM-5

When a psychologist or psychiatrist needs to figure out which, if any, specific disorder an individual has, he or she uses criteria that are laid out in the book Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, which is published by the American Psychiatric Association. The current edition of the book, published in 2013, is the 5th; it is abbreviated DSM-5 (or sometimes just DSM).

DSM-5 is essentially a checklist, a list of symptoms only (and how long they need to be present), which makes it seem as if it would be easy to use to classify people. Do not give in to the temptation to pick up the DSM (which is probably in your school’s library and is available in online editions) and diagnose your friends, however. The DSM was designed to be used by trained professionals, and application of the criteria requires substantial clinical judgment. Psychological tests also play a role in making decisions. The problem is that the categories have fuzzy boundaries. Although some clear cases are fairly easy to judge, many people present symptoms that could place them into a number of different categories of disorders. Also, many disorders occur together with other disorders, making it very difficult to reach a definitive diagnosis.

Compounding the difficulty of using the DSM-5 criteria is the fact that clinical judgments are not perfectly reliable; in other words, diagnoses using the DSM-5 are not always consistent from one clinician to another. Each new edition of the DSM is an improvement over the previous editions, and judgments that clinicians make for most diagnostic categories now have good reliability. That said, DSM-5 has been criticized for encouraging false positive diagnoses (a diagnosis of a disorder when none exists). Many disorders, such as major depressive disorder, bipolar II disorder, and attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder in adults now require lower thresholds to receive a diagnosis in DSM-5 compared to earlier editions. Although this is likely to pick up some genuine cases that would have been missed using the earlier criteria, it is also likely that false positives will occur as a result (Wakefield, 2016).

For each type of disorder, the DSM-5 describes both central features, the features that are most important for diagnosis, and associated features that can help a diagnosis. These secondary features are common to the disorder but may be less helpful because they occur in fewer cases than the central ones or occur in many different disorders (making them less useful for determining which disorder a person may be suffering from). The DSM-5 also gives information about prevalence, risk factors, available diagnostic measures, the way the disorder progresses, and information to help distinguish similar disorders.

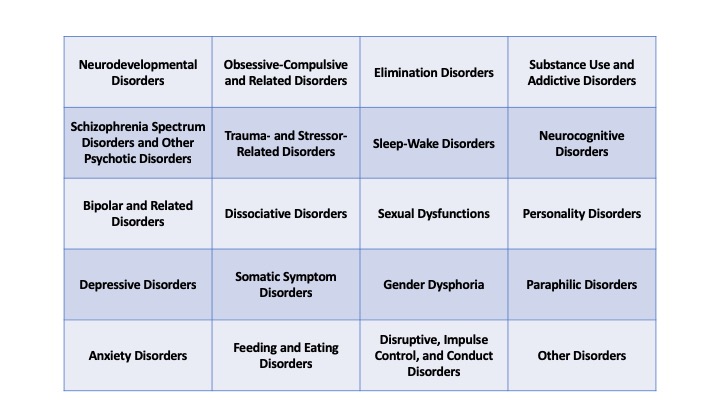

There are twenty major categories of disorders in the DSM-5, covering about 150 different possible diagnoses.

Becoming familiar with all these diagnoses and being able to tell which apply to a particular client is one of the challenges of becoming a professional clinical psychologist.

Debrief

- Try to think of some examples of when you may have perceived someone differently because of a label (even if it was not a label relating to a psychological disorder).

- What ways can you suggest that society could change some of the negative attitudes toward people who suffer from psychological disorders?

- What ways can you help change some of the negative attitudes toward people who suffer from psychological disorders?

28.2. Depressive and Bipolar Disorders

Activate

- If you have never suffered from major depressive disorder, how would you characterize the differences between a depressed mood and clinical depression?

- If you have suffered from major depressive disorder, how would you describe the differences between a depressed mood and clinical depression?

It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that mood disorders are the most important psychological disorders. Mood disorders have a disturbed mood as the main feature. They include depressive disorders, such as major depressive disorder (commonly called depression) and persistent depressive disorder, and bipolar disorders, along with a few others.

Mood disorders are among the most common disorders. 264 million people worldwide suffer from depressive disorders, with 163 millions suffering from major depressive disorder alone (GBD, 2018). In the US, about 17% of the population can expect to suffer from at least short-term depression during their lives (Kessler et al., 1994). Throughout the world, women are twice as likely as men to suffer from depression (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2002). College students are at particularly high risk. In one recent survey of over 30,000 college students in the US, 41% reported at least moderate depression (based on answers to a survey designed to detect it), including 21% whose depression was rated as severe (Duffy et al., 2019).

Depression touches many aspects of the lives of people who suffer from it, as well as the lives of friends, family, loved ones, and coworkers. Depressive disorders are the third of the leading cause of disability in the world (GBD, 2018). They are also a risk factor for cardiovascular illness, suicide, and other serious diseases.

Depressive Disorders

It is a rather unfortunate coincidence that the English language uses the same word, depression, for a short-term, mildly sad feeling and a serious medium- or long-term psychological disorder. It is entirely natural for a person who is not suffering from major depressive disorder to say, “I’m depressed.” The surface-level similarity between a “depressed mood” and “depression” leads people to some serious misconceptions about the disorder. For example, when a healthy person feels depressed, she may be able to distract herself with some pleasant activity or otherwise reverse the feeling so she feels better. It is not difficult to imagine that this person would then wonder why someone suffering from clinical depression cannot do the same thing.

You can use your experiences of depressed moods to imagine what depression might feel like, but we should caution you: Depression is a complex disorder, and there are very many possible symptoms, so there really is not a “typical” profile.

Depression often goes away by itself, a fact that also leads some people to doubt that it is a true disorder. “How could it be a real illness,” they wonder, “if it goes away on its own?” We must confess, we have never understood this argument. Very many diseases and disorders go away on their own at least occasionally, for example, colds, the flu, and rashes; that is what our immune system is supposed to do, to make diseases go away. That does not make the diseases any less “real,” however. Even cancer sometimes spontaneously goes into remission. By the way, it is probably more correct to call depression’s disappearance a remission rather than a cure, because it frequently recurs after it goes away.

What Does Depression Look Like?

To be diagnosed with major depressive disorder, the DSM specifies that a person must have at least one major depressive episode: 2 or more weeks of at least five of the following nine symptoms (but at least one of the first two is required):

- Depressed mood, most of the day, nearly every day (can be irritability in children and adolescents)

- Loss of interest or pleasure in nearly all activities (this is called anhedonia)

- Weight loss when not dieting, or decrease or increase of appetite

- Insomnia or hypersomnia (sleeping too much)

- Psychomotor agitation or retardation

- Fatigue or loss of energy

- Feelings of worthlessness or inappropriate guilt

- Difficulty concentrating, making decisions

- Recurrent thoughts of death or suicide (suicide ideation), or suicide attempt or plan

You might note that depression hits us with emotional and motivational symptoms, physical symptoms, and cognitive symptoms, thus spanning an extraordinary range of our everyday functioning.

This is a notable list of symptoms in another important respect, too. There are nine possible symptoms, three of which do not specify the direction of the change in behavior; sleep, appetite, and activity level might increase or decrease. In addition, people from different cultures tend to report different symptoms when they experience depression. For example, people from Latino/Latina and Mediterranean cultures often report “nerves” and headaches; people from Asian cultures report that they are weak, tired, and unbalanced. As you might guess, it can be quite difficult to recognize depression. Which of these two individuals would you say is depressed: Joe, a 27-year-old graduate student who has been sad and feels worthless, spends most of the day sleeping or sitting on the couch, and has been eating more than he usually does for the past month? Or Jennifer, a 17-year-old high school junior unexpectedly quit the cross country team, and has been irritable and feeling overly guilty about an argument she had with her mother three weeks ago and is unable to sleep, eat, or sit still? In truth, both could be suffering from depression.

Many additional symptoms, such as anxiety and worrying, obsessive thoughts, phobias, panic attacks, and physical pain, often occur along with depression. Many people report difficulty with their social relationships, marriage, sexual functioning, occupation, or school. Also, increases in alcohol and drug use are common. Finally, when children have depression, they are more likely to suffer physical symptoms, irritability, and social withdrawal.

Depression and Suicide

It is worth spending some time on one specific symptom of depression, the recurrent thoughts of death or suicide. As we are sure you realize, some depressed individuals act on those thoughts. The CDC reports that suicide is the 10th leading cause of death in the US and the 2nd highest cause of death for people ages 15 to 24, behind only accidental death. (Note these estimates do not include deaths from COVID-19.) Although no one can know for sure, it is estimated that for every completed suicide, there are 8 to 25 attempted suicides. Three times as many women as men attempt suicide, but four times as many men as women die by suicide. The difference in completed suicides appears to be largely a result of the different methods that men and women choose; in particular, women are more likely than men to ingest poison, whereas men are more likely than women to choose a more deadly method, such as shooting.

Suicide is clearly related to depression, but the two are not synonymous. The large majority of people who suffer from depression do not attempt or complete suicide. On the other hand, the more serious the depression and the more suicide thoughts present, the more likely suicide is. Also, if you look at people who do commit suicide, 60% of them suffered from a mood disorder. This can be confusing, so let us repeat it another way that highlights the difference between the points:

- If someone has a mood disorder, he or she probably will not commit suicide.

- If someone commits suicide, he or she probably had a mood disorder.

It is very difficult to predict that a person suffering from depression will commit suicide because the same pattern exists between suicide and other risk factors as well. For example, a very small percentage of people who abuse drugs and alcohol commit suicide, but a larger percentage of people who commit suicide had abused drugs or alcohol. Other factors that increase the risk of suicide include impulsiveness, aggressive tendencies, previous suicide attempts, family history of suicide, and previous sexual abuse (NIMH, 1999). Also, some individuals, especially people under 24, attempt suicide after the suicide of a close friend or a celebrity, a phenomenon known as suicide contagion (CDC, 2002; Gould et al., 2003; Poijula et al., 2001).

The bottom line: If an individual reports that he or she has been thinking about suicide, you must take the comment seriously. Although most people who communicate that they are thinking about suicide do not follow through, most who commit suicide did communicate their intent in advance.

anhedonia: loss of interest or pleasure in nearly all activities

hypersomnia: sleeping too much

suicide contagion: an individual’s attempt at suicide following the suicide of a close friend or a celebrity

suicide ideation: recurrent thoughts of death or suicide

Persistent Depressive Disorder

You can think of persistent depressive disorder as a long-term milder form of depression. To be diagnosed, an individual must have a depressed mood most of the day for more than half of the days for two years or more. In addition, two of the following symptoms are required:

- Poor appetite or overeating

- Insomnia or hypersomnia

- Low energy or fatigue

- Low self-esteem

- Difficulty concentrating or making decisions

- Feelings of hopelessness

Bipolar Disorders

You may know bipolar disorderby its older name, manic-depression. You probably think of it as the disorder in which an individual has periods of mania interspersed with periods of depression. It is a bit more complicated than that though. There are two main types, bipolar I disorder and bipolar II disorder. They are distinguished by the presence of a manic episode or a hypomanic episode, and by whether a major depressive episode is required or not.

A diagnosis of bipolar I disorder requires a manic episode only. A major depressive episode is not required (but the large majority with Bipolar I do end up having one or more). A manic episode consists of one week of abnormally elevated or irritable mood and increased goal-directed activity or energy. In addition, three of the following symptoms are required (four if the mood is only irritable):

- Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity

- Decreased need for sleep

- More talkative than usual

- Racing thoughts

- Distractibility

- Increase in goal-directed activity or psychomotor agitation

- Excessive high-risk behavior (e.g., buying sprees, sexual indiscretions)

Sometimes people have delusions, or false beliefs, when they are experiencing a manic episode. For example, an individual might believe that she can run a marathon without any training. It is also very common for someone experiencing a manic episode to deny that they are ill or need treatment.

A diagnosis of bipolar II disorder requires at least one hypomanic episode and major depressive episode (exactly the same as in major depressive disorder). A hypomanic episode is a four day period over which a person experiences the same symptoms as required for a manic episode.

manic episode: the active phase of bipolar I disorder. Often involves high energy and good mood; it can also include irritability, inflated self-esteem, feelings of grandiosity, and delusions.

delusions: false beliefs

hypomanic episode: a four day period over which a person experiences the same symptoms as required for a manic episode

Causes of Depression and Mood Disorders

Befitting such hard-to-pinpoint disorders, the causes of depression and other mood disorders are complex. Biological and genetic factors are both involved, as are psychological and sociological factors. Because the concepts are complex but similar across different specific disorders, we will focus on major depressive disorder to illustrate the ideas and keep information at a manageable level.

Biological Factors

Many people have heard that depression is caused by a “chemical imbalance in the brain.” Honestly, that is not a very useful statement, though, as the changes that we have observed in people who suffer from depressive disorders are profound. Oakes et al. (2016) identified at least 34 separate brain areas that have been shown to be affected in major depression. Two of the key ones appear to be shrinkage of the hippocampus and cingulate cortex.

In addition, there appears to be something abnormal with neural transmission, notably in circuits involving pre-frontal cortex and limbic system. Reduced levels of several different neurotransmitters have also been observed, including GABA, glutamate, serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine. In some cases, particularly for serotonin, faulty receptor sites have also been identified.

Whew! Now we think you can begin to understand why depression has such a wide array of possible symptoms (and, as you will see, only moderately effective treatments).

Even if we had a perfect account of the neurotransmitter and brain activity involved in depression, we would still not have an explanation of the disorder. What we would have is a detailed description of the disorder at a very fine level. A description tells you what a phenomenon looks like, while an explanation tells you how or why the phenomenon occurs. To get an explanation of depression, we would need to know why these brain and neurotransmitter changes occur.

Genetic and Epigenetic Factors

There is solid evidence that mood disorders have a genetic component, which by now should come as no surprise to you. Reviews of behavior-genetics research have discovered heritabilities around 37% for major depressive disorder. The environmental contributions appears to come largely through individual environments, rather than through environmental conditions that are common to all members of a family (Lohoff, 2010). Given the complexity of depression, it probably comes as no surprise to you that no single gene variations have been implicated in all, or even most, cases of depression. Genes involved in serotonin transport and reception have been cited frequently as important candidates, however. A recent review has also suggested that epigenetic changes in DNA expression are indeed associated with depressive disorders (Li et al., 2019). There are few longitudinal studies, however, so it is not yet clear if these epigenetic changes are causes or consequences of depressive disorders.

Psychological Factors

Depressive episodes often follow stressful experiences. Of course, that does not mean that everyone who has a stressful experience will develop depression. We can begin to understand and predict who will, however, if we consider the role of genes. In essence, we can think of depression as an example of a gene x environment interaction (Module 10). For example, one line of research has found that individuals who had a particular version of a gene related to serotonin were likely to develop depression but only if they experienced serious life stressors (Caspi et al., 2010; Caspi et al., 2003). The researchers noted that many people who have the gene do not ever develop depression, and others who do not have the gene do develop depression. Clearly, something is still missing from the explanation. One likely possibility is that additional genes are involved.

A second possibility, also likely, is that cognition is involved. The thoughts of worthlessness and hopelessness that accompany depression are, for many sufferers, extreme versions of the kinds of thoughts that they have had for many years. Many researchers believe, then, that a negative style of thinking is not simply a symptom of depression but is a contributing cause. In other words, some people develop a habit of thinking in ways that make it more likely that they will develop depression.

Imagine that you are doing poorly in school and nothing you try is working. You devote every waking moment to studying or attending class, you spend many hours with your professors and in your college’s academic assistance areas, and you even hire a private tutor. Still, your grades do not improve one bit. Many people would finally give up, as they come to believe that nothing they can do will make a difference. In effect, they learn that they are helpless. This idea is one of the most important discoveries about the kind of thinking that puts people at risk for depression. Martin Seligman and his colleagues discovered it in the 1960s in some famous research with dogs.

The researchers placed two dogs in an apparatus that administered electric shocks. One dog was able to stop the shocks by pressing on a panel. This is a simple example of negative reinforcement, and the dog quickly learned to avoid the electric shocks and suffered no ill effects. The other dog was connected to the same shock generator as the first dog. This second dog received electric shocks whenever the first one did, but this dog did not have the ability to control the shocks. Although the two dogs received the same amount of shock, only the second one showed any negative effects. This dog essentially gave up and became passive and lethargic, much like a depressed person. Even if the dog could later escape the shocks, it made no effort to do so (Seligman & Maier, 1967). Seligman called the phenomenon learned helplessness.

Seligman and his colleagues have combined this concept with some of their concepts about optimism (Module 25). They have observed how differently optimists and pessimists look at the things that happen to them:

Perception of Successes and Failures by Optimists

| Successes | Failures |

| Are my fault (Personal) | Are someone else’s fault |

| Affect many other areas of life (Pervasive) | Are specific to this experience |

| Last forever (Permanent) | Are temporary |

Perception of Successes and Failures by Pessimists

| Successes | Failures |

| Are someone else’s fault | Are my fault (Personal) |

| Are specific to this experience | Affect many other areas of life (Pervasive) |

| Are temporary | Last forever (Permanent) |

When an individual learns that he is helpless in a specific situation, he tries to explain why (Abramson et al., 1978). If he has a pessimistic style of thinking—he blames himself, thinks that it will affect other areas of life, and thinks it will last forever—he is likely to generalize the helpless feeling to many other situations. The result is a generalized learned helplessness and a very high risk of depression. This link between depression and thinking style has been demonstrated in a great deal of research (Abramson et al., 2002).

Sociocultural Factors

One way to think about the role of sociocultural factors in depression is to realize that when significant life stressors that can influence individuals become increasingly common, they cross over to become cultural factors. Let us consider two briefly. First, we have already seen that a life event like unemployment can lead to long-term changes in happiness (Module 25). And unemployment can certainly qualify as a major life stressor that puts one at risk of developing depression. Consider these in a larger context. One recent study found that people who were employed at one-time point were less likely to suffer from major depressive disorder at a later time point. Forty-three million workers in the US filed for unemployment between the start of the COVID-19 economic downturn and May 30, 2020. This is one (of many) reasons why experts have been concerned about an increase in mental illness as another tragic side effect of the pandemic (also see Module 29).

A second reason is loneliness. A recent meta-analysis of 88 studies (with over 40,000 individual people) found that loneliness has a moderate effect on depression (Erzen & Çikrikci, 2018). One national survey of 20,000 individuals over 18, conducted on behalf of the insurance company Cigna, revealed the following sobering statistics:

- 54% said that they often feel like no one knows them well

- Nearly half said that they sometimes or always feel alone (46%) or left out (47%)

- 43% said that their relationships lack meaning and the same number said that they sometimes or always lack companionship.

We could continue, but we want you to keep reading.

Here, if we put you in a bad mood, we will try to make it up to you. The news is not all bad. Contrary to what experts had feared, the early results are that the COVID-19 physical distancing recommendations did not seem to increase loneliness in general, as indicated by an unrelated survey of 1,500 individuals (Luchetti et al., 2020). In other words, things are bad, but at least they are not getting worse. And in fact, there is even some cause for optimism in this study, as respondents reported that their perceived level of social support had increased over the first few months of the pandemic. This suggests that if we focus on the need for social support and to reduce loneliness, it is almost certainly a goal we can accomplish, with an expected decline in illnesses like major depressive disorder (and frankly, many other illnesses as well).

Debrief

- Which of the cognitive and sociocultural factors that contribute to depression can you recognize in your own life? What, if anything, do you do to protect yourself from the effects of these factors?

28.3. Treatments For Mood Disorders

Activate

- Why do you think that antidepressant drugs like Zoloft, Prozac, are Cymbalta are so popular these days?

- Are you generally in favor of or against the use of antidepressant drugs for the treatment of depression? Why?

- What do you think the important elements of a psychotherapy treatment for depression should be?

The roles that neurotransmitter activity and negative thinking patterns play in depression are among the most important discoveries to advance our understanding of mood disorders. It should come as no surprise, then, that treatments based on these discoveries have emerged as the most successful ways for individuals to cope with these serious disorders. Specifically, cognitive-behavioral therapy and antidepressant medication are quite effective treatments for major depressive disorder and for the depressive symptoms of bipolar disorder.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

The most effective psychotherapy for depression is cognitive-behavioral therapy, a simple combination of methods derived from cognitive theory and behavioral or learning theory. One key aspect of these therapies is that they try to help the client break habits, some of which have been established over a lifetime. It is not practical to expect that a one-hour conversation with a psychologist, once or twice per week, will have much of an impact. The client has to use the strategies throughout the week; in a sense, these therapies include a great deal of homework for the client.

The many specific therapies that make use of cognitive techniques all share important aspects. First, they are based on the observation that our thoughts are related to but separate from our feelings. Second, they help clients to recognize their own specific maladaptive or irrational thinking that contributes to depression. Third, they try to teach the client new ways of thinking. The main differences among cognitive therapies are specifics about the different kinds of thinking patterns that are common and specific techniques to recognize and stop them. For example, many cognitive therapies help clients to recognize the negative thoughts that they have about themselves, the world, and the future, an approach first described by psychologist Aaron Beck (1967).

In the behavioral part of cognitive-behavioral therapy, the therapist can help the client realize how aspects of the environment contribute to the depression. Then the client can be encouraged to avoid situations that lead to depression. When situations cannot be avoided—as, for example, with someone who becomes depressed about having to visit with relatives over the holidays—the therapist can teach the client new skills (such as relaxation) to solve problems or to cope with distress.

Antidepressants

Another common treatment for mood disorders—best used with psychotherapy but in reality often an alternative to it—is antidepressant medication. Recent data from the CDC showed that 13.2% of US adults were currently taking an antidepressant (Brody & Gu, 2020). The most common type of antidepressant is called a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI). Commonly prescribed drugs such as Prozac and Paxil fall into this category. They were developed to treat problems in the neural transmission process. After the neurotransmitter serotonin is released into synapses, it is reabsorbed by the axon terminal button, a process called reuptake. SSRI antidepressants increase the effects of serotonin by preventing reuptake, so the serotonin that is available in a synapse stays there longer. SSRI’s are very common, in large part because they are a great improvement over older kinds of antidepressants. Although SSRI’s and older antidepressants are equally effective, SSRI’s have much less severe side effects. However, these side effects are very common. They include nausea, diarrhea, headaches, jitteriness, and sexual dysfunction. SSRI’s have also been used to treat other disorders, such as anxiety disorders.

One side effect that has received a great deal of well-deserved scrutiny over the years is an increase in suicidal thoughts among people who take SSRI’s. For adults, this does not seem to be the case, but there is an increase in these thoughts for children and adolescents. Luckily, there does not seem to be an increase in completed suicides, but physicians and caregivers of children and adolescents who take SSRI’s should be extra vigilant (Nischal et al., 2012).

Seventy-nine percent of antidepressants in the US are prescribed by primary care physicians, not psychiatrists (Barkil-Oteo, 2013). Although making antidepressants available through all medical doctors increases access to this important treatment option, it means that the drugs are being prescribed by people who might have little specialized training in psychological disorders. In addition, many doctors frequently prescribe antidepressants without requiring that psychotherapy be used as well.

You may now be wondering how effective SSRI’s are at treating depression. In order to determine the efficacy of a drug, researchers conduct tightly controlled experiments in which they compare the improvement of participants that receive an SSRI to participants that receive a placebo pill. In 2008, a group of researchers set out to perform a meta-analysis of these experiments with a key improvement on prior research: they included both published and unpublished data (Kirsch et al., 2008). This is important, because studies with positive results showing that the drug worked are more likely to be published. (Remember the file drawer problem from Module 4?) By including studies that were conducted but never published, the researchers aimed to get a more accurate picture of how well SSRI’s worked.

Across all of these trials, the researchers found that SSRI’s did not outperform placebo for mild, moderate, or even severe depression. Improvement in the placebo group was considerable, duplicating more than 80% of the improvement in the SSRI group. The only patients for whom SSRI’s were notably superior to placebo were patients with very severe depression, and this was not because of an increased response to the medication, but instead a decreased response to the placebo pill (Kirsch et al., 2008). These findings are also in line with the recent research questioning the serotonin hypothesis of depression. After all, the use of SSRI’s depends on the premise that serotonin transmission is faulty in individuals with depression.

Now, what should we do with this information? We will not presume to have all of “the answers”, but we will try to share our perspective as psychology professors, consumers of research, and, importantly, consumers of healthcare. We do not dispute that SSRI’s have been a component of many successful treatment regimes and that some individuals credit SSRI’s with nothing less than saving their lives. The research we have shared does not invalidate anyone’s individual experience with the drug. It does, however, make us question what the “active ingredient” in this treatment really is. Some researchers have suggested that only 25% of the improvement observed in response to SSRI’s is actually due to the activity of the drug itself – 51% is attributable to the placebo effect and the remaining 24% can be explained through the natural progression and resolution of the disorder on its own (Kirsch & Sapirstein, 1999).

Is this necessarily a bad thing? After all, you could make an argument that the job of a medical provider is to improve someone’s condition and if a doctor can accomplish that through eliciting hope and activating the “self-healing” properties of a placebo, maybe they should do it. It is important to note, however, that SSRI’s do not come without risks. The side effects tend to be more mild than those of some other psychiatric medications, but again, they are very common and can be very distressing. So, should SSRI’s still be prescribed? There is no one single answer to this question that will be correct for each person reading this book. Deciding to take (or not take) a medication requires evaluation: you, under the careful guidance of a qualified doctor, must weigh the potential costs and benefits. These costs and benefits likely differ for different people. In sharing these findings with you, we hope that you can be an informed decision-maker. There is, however, one final implication of these findings that we all agree on: doctors (psychiatrists and general practitioners) should be aware of this research on the effectiveness of SSRI’s and they should not push people to take medication if they do not want to. (See Bschor & Kilarski, 2016, for an excellent review and expert commentary on the utility of SSRI’s given recent challenges to their effectiveness compared to placebo.)

Other lines of research have compared the effectiveness of medication to psychotherapy. The evidence suggests that both work. When research pits antidepressants against psychotherapy—specifically, cognitive-behavioral therapy—the two usually fare about equally well; about half of patients get better (Kappelmann et al., 2020). Nothing about depression implies that one needs to be limited to a single treatment option, however. The clear winner in these studies of treatment for depression, with more than 70% getting better, is the combination of antidepressants and cognitive-behavioral therapy (Keller et al., 2000; TADS, 2004).

cognitive-behavioral therapy: a simple combination of methods derived from cognitive theory and behavioral or learning theory

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor: a class of antidepressant drugs that works by preventing the reabsorption of excess serotonin in synapses

Other Treatments for Mood Disorders

A number of other treatments have been used for mood disorders; some are reserved for serious cases:

- Lithium is commonly used for bipolar disorder. This drug works better for mania, so many people who have bipolar disorder also take an antidepressant for the depressive episodes. There is some evidence that cognitive-behavioral therapy is also effective for bipolar disorder (Jones, 2004).

- Vagus nerve stimulation was approved by the FDA in 2004 for severe, treatment-resistant depression. The vagus nerve brings information from other parts of the body to the hypothalamus and amygdala, brain areas that seem to be involved in depression (see sec 11.2). Patients have a device surgically implanted in the chest that provides stimulation of the vagus nerve, a nerve that sends information to the brain from the head, neck, chest, and abdomen. Research support for this treatment was shaky, and the benefits appeared in these studies only after one to two years using the therapy, but the severity of the disorder led the FDA to approve it.

- Electroconvulsive therapy is occasionally used for severe depression that is resistant to all other forms of treatment. After sedatives and muscle relaxers are administered, an electric current is passed through the brain, which starts a convulsion. Treatment usually involves 6 to 12 sessions over about a two-week period. The patient suffers some memory loss, but the depression lifts in most cases. Up to 85% will become depressed again, however, and may need additional treatment (Fink, 2001).

- Transcranial magnetic stimulation is another possible therapy for depression that has not responded to other treatments. In this therapy a magnetic field is introduced over the left prefrontal cortex. Twenty daily sessions seems to improve short-term symptoms in up to 50% of patients whose depression had been resistant to other forms of treatment. Although there were few studies that looked at longer-term results, those that did found that most had improvements lasting at least 2 – 5 months (Gellerson & Kedzior, 2018).

Debrief

- Once again, are you generally in favor of or against the use of antidepressant drugs for the treatment of depression? Why?

- What is your opinion about the Food and Drug Administration’s decision to put the black box warning label on antidepressants?

- In the Debrief for section 28.2, you are asked to describe strategies that you might have used to protect yourself from the cognitive and sociocultural factors that contribute to depression. Which of the strategies remind you of the therapies described in this section?