29 Other Psychological Disorders and Treatment

We considered giving this module the subtitle “The Common, the Severe, and the Controversial.” It is extremely likely that you will be familiar with the four categories of disorders that we will describe because, well, they are common, severe, or controversial. Anxiety and related disorders, characterized by intense fear or nervousness, are “the common.” For example, a great many people suffer from social and specific phobias, and occasional panic attacks are common among the non-disordered population. Chances are quite good that you know someone who suffers from an anxiety disorder. Schizophrenia spectrum disorders are “the severe.” If you have an image of a hospitalized psychiatric patient who is confused and confusing, talks incoherently, and displays the wrong emotions, it is probably based on schizophrenia. Although long-term hospitalization is no longer the norm, sufferers of schizophrenia do indeed resemble this common image. Personality disorders and dissociative disorders are “the controversial.” They are difficult to diagnose, and their causes are disputed. Making matters worse, the cinematic “homicidal maniac” so responsible for our lingering fear of violence among the psychologically disordered is usually based on one of these controversial disorders.

Module 29 has four sections. Section 29.1 describes the extremely common anxiety and related disorders. Section 29.2 turns to perhaps the most severe of the psychological disorders, schizophrenia spectrum disorders, and section 29.3 tackles the controversial, especially antisocial personality disorder and dissociative identity disorder. Section 29.4 describes what we have discovered about the effects of COVID-19 on mental health. Finally, section 29.5 concludes the module with a brief description of some additional therapies and a discussion of factors that different therapies share.

29.1 Anxiety disorders

29.2 Schizophrenia

29.3 Personality disorders and dissociative disorders

29.4 COVID-19, quarantines, school closures, and mental health

29.5 Therapy in sum

READING WITH A PURPOSE

Remember and Understand

By reading and studying Module 29, you should be able to remember and describe:

- Anxiety disorders: generalized anxiety disorder, panic attacks, panic disorder, agoraphobia, phobias, systematic desensitization (29.1)

- Posttraumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (29.1)

- Schizophrenia: positive and negative symptoms, subtypes, biological factors and causes, antipsychotic medication (29.2)

- Personality disorders, antisocial personality disorder (29.3)

- Dissociative disorders, dissociative identity disorder (29.3)

- Short- and long-term changes in mental health associated with the COVID-19 pandemic (29.4)

- Psychodynamic therapy: free association, transference, projective tests, interpersonal therapy (29.5)

- Client-centered therapy (29.5)

- Shared factors in therapy (29.5)

Apply

By reading and thinking about how the concepts in Module 29 apply to real life, you should be able to:

- Recognize examples of the different anxiety disorders (29.1)

- Recognize examples of schizophrenia, including subtypes (29.2)

- Recognize examples of antisocial personality disorder and dissociative identity disorder (29.3)

Analyze, Evaluate, and Create

By reading and thinking about Module 29, participating in classroom activities, and completing out-of-class assignments, you should be able to:

- Outline how you might plan systematic desensitization for a specific fear or anxiety that you commonly experience (29.1)

- Connect what we have learned about the changes in mental health associated with the COVID-19 pandemic to historical trends and to other topics from the text (for example, social development) (29.4)

- Comment on the opinion that “psychological therapy is more an art than a science” (29.5)

29.1. Anxiety and Related Disorders

Activate

- If you have never suffered from an anxiety disorder, how would you characterize the differences between everyday nervousness and an anxiety disorder?

- If you have suffered from an anxiety disorder, how would you describe the differences between everyday nervousness and an anxiety disorder?

Whenever we experience an emotion or find ourselves in a physically or psychologically stressful situation, our bodies react with sympathetic nervous system arousal—the fight-or-flight response. Often, the arousal is experienced as anxiety, a feeling roughly similar to nervousness or fear. Usually, anxiety is reasonably mild, and it goes away soon after the arousing situation changes. But sometimes anxiety becomes a problem; it lasts so long or is so distressing that the individual cannot function or is able to control the anxiety only by engaging in strange, maladaptive behaviors. When that happens, the individual is said to be suffering from an anxiety disorder.

The specific anxiety disorders we will describe in this section are panic disorder and agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder, and phobias. In addition, we will describe two additional disorders: obsessive-compulsive disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder. On the surface, all of these disorders may not seem very similar. Although it is true that each disorder has features that distinguish it from the others, the feature that they all share in common is out-of-control anxiety, anxiety that causes severe distress or interferes with daily functioning.

anxiety: a feeling roughly similar to nervousness or fear

anxiety disorder: a category of psychological disorders marked by very distressing anxiety or maladaptive behaviors to relieve anxiety

Panic Disorder

An individual suffers from panic disorder if he or she experiences unexplained panic attacks. Panic disorder itself is not very common; about 1% – 2% of the population can expect to have it during their lifetime. Because panic attacks often occur in all of the anxiety disorders, and they are common among people who suffer from depression, as well, it makes sense to begin by describing them. A panic attack is a sudden dramatic increase in anxiety, marked by intense fear and (commonly) a feeling of doom or dread. It may be accompanied by physical symptoms, such as pounding heart, sweating, trembling, chest pain, nausea, abdominal distress, shortness of breath, and dizziness; it may also be accompanied by disruptive thoughts and feelings, such as feelings of unreality or being detached from oneself, fear of dying, and fear of losing control.

Panic attacks may be unexpected, or they may typically follow some cue. Cues may be external—for example, an individual has a panic attack when about to give a speech—or they may be internal—for example, when the person’s heart is pounding, creating the fear of having a heart attack. Occasional panic attacks are quite common; up to 40% of young adults report that they have had them (King, Gullone, & Tonge, 1993). But if the attacks are common or severe and they interfere with everyday functioning, they may signal an anxiety disorder. If the sufferer has recurrent, unexpected panic attacks, it signals panic disorder. Otherwise, the panic attacks will be considered a symptom of another disorder.

Recurrent panic attacks often lead sufferers to avoid situations or people associated with the attacks. The avoidance may turn into agoraphobia, anxiety about being unable to escape from or get help in a situation in which a panic attack is expected. People often think of agoraphobia as fear of leaving the house or fear of crowds. At a more basic level, however, it is better to think of agoraphobia as fear of panic attacks and of being stranded away from safety and helpers when one strikes. Many people who suffer from agoraphobia are able to venture out when they are accompanied by someone. In addition, they may have a number of “safe places” among which they can comfortably travel.

panic attack: a sudden dramatic increase in anxiety, marked by intense fear and (commonly) a feeling of doom or dread

panic disorder: an anxiety disorder marked repeated unexplained panic attacks

agoraphobia: an anxiety disorder marked by anxiety about being unable to escape from or get help in a situation in which a panic attack is expected

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

People who have Generalized Anxiety Disorder seem to always be tense and anxious about everything. The disorder is characterized by six months or more of excessive anxiety or worry more days than not about different events or activities– not necessarily about everything, but about a variety of different parts of their lives. In addition, three or more of the following symptoms are required:

- Feeling restless or on edge

- Easily fatigued

- Difficulty concentrating or mind going blank

- Irritability

- Muscle tension

- Sleep disturbance

Phobia

There are three different kinds of phobias, agoraphobia, which you have already seen, specific phobias, and social anxiety disorder (social phobias). Phobia, as you probably know, means fear; it is from ancient Greek language. (The names for different phobias were generated by tacking the Latin or Greek word for the feared object or situation to the front of phobia, as in “arachnophobia,” or fear of spiders.) A phobia, then, is an intense fear or anxiety associated with a specific object or situation. Although many people report feeling uneasy or fearful in the presence of certain objects or in certain situations, an individual suffering from a phobia has intense anxiety that is out of proportion to the threat posed. Panic attacks in the presence of the feared object or situation are common. Although sufferers realize that their fears are unreasonable or excessive, their fear is so intense that it interferes with the person’s everyday functioning.

Agoraphobia, although technically a phobia, never appears alone; it is always a symptom of another disorder, such as panic disorder. The other two major types of phobias, specific phobias and social anxiety disorder (social phobias), do appear as their own disorders. Specific phobias are fears of particular objects or situations, such as heights, spiders, water, or flying. Specific phobias are quite common. Up to 10% of the US population experiences specific phobias, although very few seek treatment for them (Kessler, et al. 1994). Social anxiety disorder is also quite common; more than 12% of the population can expect to have one during their lifetime (Kessler, Stein, & Berglund, 1998). Social anxiety disorder (social phobias) is, at its core, the fear of being judged by others or of being embarrassed; people who suffer from it are intensely fearful that they will say or do something wrong or inappropriate. Social phobias are commonly manifest as a fear of speaking in public or performing, of social situations such as parties, or of interactions such as meeting people. Because social situations are harder to avoid than specific objects or non-social situations, social phobias tend to be more burdensome than specific phobias are.

It can be easy to confuse social anxiety disorder and a specific phobia of the same type of situation. The key is to look for the fear of being evaluated to make it social anxiety, otherwise it is a specific phobia.

phobia: an anxiety disorder marked by an intense fear or anxiety associated with a specific object or situation

specific phobias: an anxiety disorder marked by fears of particular objects or situations

social anxiety disorder/social phobias: an anxiety disorder marked by the fear of being judged by others or of being embarrassed in social situations

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) used to be classified as an anxiety disorder. As such, it does have a significant anxiety component; it comes from obsessions, persistent, uncontrollable, inappropriate thoughts, impulses, or images. Obsessions are usually not related to any real-life problems that the individual might be facing. Common obsessions include thoughts about contamination (for example, thinking that there are germs in restaurant food), doubts (for example, wondering if the gas stove was left on), aggressive impulses (for example, an impulse to hurt one’s children), and sexual thoughts. Many people have occasional images or impulses like these, but they do not cause a great deal of distress because they can be banished from thought without much difficulty. People with obsessive-compulsive disorder try to ignore or suppress the thoughts, and if they fail, they turn to compulsions to help. Most sufferers of OCD do end up having both obsessions and compulsions.

A compulsion is a repetitive action or thought (think of it as a physical or mental act) that is intended to reduce the anxiety of an obsession. Some compulsions reduce anxiety because they address the concern contained in the obsession. For example, someone who is obsessed about leaving the stove on may check it every 10 minutes. Other compulsions might work through distraction; every time the individual thinks of hurting his children, he touches both of his knees ten times with each finger. Compulsions can be very elaborate, by the way. The most common compulsion is hand-washing; contamination by germs is a very common obsession.

In order to be diagnosed with OCD according to the DSM, the obsessions or compulsions must be very distressing, take up more than one hour per day, or interfere significantly with everyday functioning.

obsessive-compulsive disorder: a disorder marked by uncontrollable, inappropriate thoughts, impulses, or images that lead to anxiety (obsessions) and repetitive action or thought that is intended to reduce the anxiety (compulsions)

compulsion: a repetitive action or thought (think of it as a physical or mental act) that is intended to reduce the anxiety of an obsession

obsessions: persistent, uncontrollable, inappropriate thoughts, impulses, or images

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Nearly everyone experiences a stress response after a traumatic experience. For example, you are extremely likely to be tense and jittery in the immediate aftermath of a serious car accident, a result of the fight-or-flight response from the sympathetic nervous system. It is quite common for an individual to have lingering anxiety for a week or more after a traumatic event. For most of us, the anxiety goes away completely before too long. Others are not so fortunate; they suffer from posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). PTSD is characterized by complex sets of symptoms that last for at least one month (often much longer than that) after experiencing a traumatic event:

One or more intrusion symptom:

- Haunting memories

- Recurrent nightmares

- Flashbacks

- Intense psychological distress or physical reactions from stimuli that remind the individual of the trauma

One or both avoidance symptoms:

- Trying to avoid memories, thoughts, and feelings

- Trying to avoid reminders of the traumatic event

Two or more changes in cognition or mood

- Inability to remember important parts of the traumatic event

- Persistent negative beliefs or expectations

- Distorted thoughts about the traumatic event leading the individual to blame self or others

- Negative emotions

- Loss of interest in activities

- Feeling separated from others

- Inability to experience positive emotions

And two or more changes in arousal and reactivity

- Irritability and angry outbursts

- Reckless or self-destructive behavior

- Hypervigilance

- Easily startled

- Problems concentrating

- Sleep disturbance

Originally, PTSD was diagnosed only for individuals who experienced extreme events that directly threatened their own lives, such as being victimized in a violent crime or experiencing war or a severe natural disaster. The diagnosis has expanded substantially. The individual must be exposed to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence– and there are several ways this can happen: through directly experiencing it, by witnessing it happening to others, by learning about it happening to someone close, or by repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details about it.

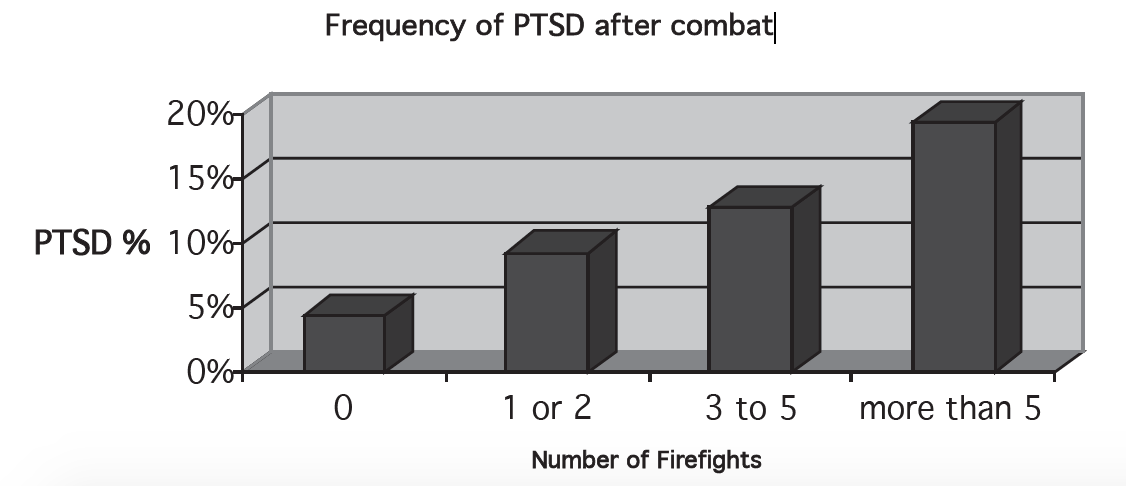

As we are sure you can guess, the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder in a group is heavily dependent on the severity of the traumas that members face. In a 2003 survey of over 1,700 US Army and Marine personnel who had been deployed in the Iraq war, 12.5% met the criteria to be diagnosed with PTSD 3 to 4 months after their return home. The more combat they experienced, the more likely they were to have post-traumatic stress disorder (Hoge et al., 2004).

Only fourteen of the 1,700 soldiers and Marines studied were women. Research had previously shown that 20% of women, but only 8% of men, suffer from PTSD after a trauma (Kessler et al. 1995), but as you can see, the frequency and severity of the trauma can increase that rate dramatically.

People who experience trauma over a very long period would be likely to suffer from PTSD as well. A survey of a representative sample of the adult (over age 15) population of Afghanistan, a country that has been nearly continuously at war for over 20 years, found that over 60% of the population had experienced four or more traumatic events in the past 10 years. Overall, 42% of the population had symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (Lopes Cardozo et al., 2004). One 2009 study found that 35.9% of children in the Gaza Strip had PTSD (Espie, et al. 2009). Large meta-analyses and reviews have found that up to 26% of civilians who live through wars will develop PTSD (Hoppen & Morina, 2019).

As you might guess, there are early reports that PTSD is an important side effect, if you will, of COVID-19. Health care workers, patients who require intensive care treatment for long periods of time, and family members who have been separated from loved ones while they die are all in danger (Kanzler & Ogbeide, 2020; Tingley et al., 2020).

Causes of and Treatments for Anxiety Disorders

Researchers have made important discoveries about the biological and psychological factors that are related to or contribute to anxiety disorders. These discoveries, especially those about psychological factors, have led to the development of effective treatments for these disorders.

Biological Factors and Causes

Heritability estimates from twin and family studies for anxiety disorders are in the 30% – 50% range, similar to depression (Hettema et al., 2001; Smoller et al., 2009).

As you certainly realize, anxiety disorders have very different features from each other. Even the anxiety or fear itself differs across the disorders. These differences show up in brain activity, as there are relatively few similarities for different kinds of anxiety. Two specific brain areas that are key are the amygdala (which you have already seen) and the insula (which you have not). The insula is located in the area between the frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes, and is divided into up 13 separate subdivisions (Uddin et al., 2017). These two areas are important in all three of posttraumatic stress disorder, specific phobias, and social anxiety disorder (Wager, 2007). The amygdala in particular might be responsible for an inflated perception of threat and emotional responses (Schmidt et al., 2018).

By now you probably realize that networks of brain areas are important for complex responses. In this case, the expectation of bad outcomes (that is, worrying or anxiety) is associated with a network including the amygdala, insula, hippocampus, cingulate cortex, and prefrontal cortex (Schmidt et al., 2018). If you are reading carefully, you might notice that several of these are the same areas as implicated in depression. The front part (anterior) of the cingulate cortex along with the insula has been nicknamed the fear network (Sehlmeyer et al., 2009). Research into pharmacological and psychotherapeutic treatments for anxiety disorders has found that brain activity in all of these very same areas are affected by the treatments (Greco & Liberson, 2016).

Learning Factors

Many cases of anxiety disorder involve straightforward applications of learning principles. Through a combination of classical and operant conditioning, ordinary fears can be transformed into the intense fear of a phobia. For example, you may have an intense fear of dogs that originated as a conditioned response to being bitten as a child (Module 6). The unconditioned stimulus of being bitten by the dog led to an unconditioned response of fear. The sight of the dog was a conditioned stimulus, which led to a conditioned fear response. Generalization could then lead you to experience the conditioned fear response in the presence of any dog.

Once a fear is established through classical conditioning, it can be strengthened considerably through operant conditioning. When you feel anxiety or fear in the presence of dogs, you are very likely to avoid them. When you avoid them, the fear goes away, so you would be likely to repeat these avoidance behaviors in the future. This, of course, is the strengthening of a behavior through negative reinforcement.

Negative reinforcement helps us to understand how the compulsive behaviors of obsessive-compulsive disorder develop as well. When an individual is extremely anxious about contamination by germs, for example, he may scrub his hands, and the anxiety goes away. The next time he feels the anxiety, he will repeat the same behavior that led to its removal previously. As the negative reinforcement–fueled cycle of anxiety and hand washing to relieve the anxiety continues, the result can be a compulsion.

Psychotherapy

Anxiety disorders are often successfully treated with psychotherapy alone—except for OCD, which responds well to treatment with a combination of SSRI antidepressant and cognitive-behavior therapy. In addition, severe anxiety can sometimes be controlled with antianxiety drugs. These drugs are often agonists for the neurotransmitter GABA. This inhibitory neurotransmitter, when released in the amygdala, reduces anxiety, so a drug that increases or mimics its activity would enhance that effect.

The specific psychotherapies that are commonly used to treat anxiety disorders are types of cognitive-behavior therapy or simply behavior therapy. The goal of the cognitive portion of therapy is similar to that for the treatment of depression, to recognize and correct specific thoughts that contribute to the individual’s anxiety (Module 28). For example, a client may be taught to recognize the shortness of breath and palpitations that precede a panic attack so that he will not mistake it for a heart attack (as is common). Sometimes, that knowledge alone is enough to prevent the panic attack (Seligman, 1994).

Although a therapist may employ many specific behavioral techniques, the most well-known one is called systematic desensitization. This technique, quite an effective treatment for phobias, is based on two important observations. First, many specific fears have been classically conditioned (see Module 6). Second, a person cannot be anxious (or fearful) and relaxed at the same time. The goal of systematic desensitization is to replace the fear-conditioned response with a relaxation conditioned response. The therapist helps this process along by teaching the client to relax in the presence of the feared conditioned stimulus. Systematic desensitization works gradually, unlike a therapy technique called flooding, in which the client is exposed immediately to the feared stimuli in an unescapable situation—the difference between, say, letting a client who fears dogs work up to facing a barking dog over a dozen encounters and simply throwing the client into a pen with a dozen barking dogs. Systematic desensitization works by asking the client to imagine frightening situations at first rather than experiencing them directly. The client and therapist prepare a list of increasingly frightening situations to imagine, starting with a very mild one. For example, a client who fears dogs might have the following list:

- Watching a television show about dogs

- Meeting a gentle puppy

- Playing with the puppy

- Standing in the same room as a gentle larger dog

- Petting a gentle dog

- Facing a barking dog while standing outside a neighbor’s front door

- Standing in the same room as a barking dog

After drawing up this list, the therapist teaches the client special techniques to relax. From here, the process is simple, although it does take some effort and persistence. The client relaxes and then imagines the first item in the list. If she is able to stay relaxed, she moves to the second item, then the third item, and so on. As soon as she feels any anxiety at all, the client stops imagining the situations and tries to relax again. Once relaxed, she can begin to imagine situations again. Eventually, the client is able to remain relaxed while imagining situations that previously caused anxiety. At this point, the client seeks some real situations that would have at one time caused anxiety while trying to maintain the relaxation response.

You may not be surprised to discover that systematic desensitization has gone high tech. Clients in virtual reality exposure therapy face their feared situations in the form of a sort of video game, a realistic computer-generated environment with which they can interact. Research has shown that virtual reality therapy is effective for two very common phobias, heights and flying, and we are awaiting research results for other kinds of phobias (Krijin et al., 2004). In one study, clients who feared flying did as well in virtual reality exposure therapy as they did in a standard therapy that used exposure to actual situations, demonstrating how useful, efficient, and relatively inexpensive the therapy can be (Rothbaum et al., 2002).

systematic desensitization: a behavior therapy in which a client learns to relax while imagining increasingly frightening situations related to his or her phobia

flooding: a behavior therapy in which a client is exposed immediately to the feared stimuli of a phobia in an unescapable situation

virtual reality exposure therapy: a behavior therapy related to systematic desensitization in which a client interacts with feared situations in a computer-generated environment

Debrief

- Have you ever had a panic attack? If so, what brought it on? Can you describe how it felt?

- Think about an event, object, or situation that makes you very anxious. How would you plan a program of systematic desensitization for your anxiety?

29.2. Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders

Activate

- Based on your prior exposure to the concept, how would you describe someone who suffers from schizophrenia?

Schizophrenia, one of the most serious of all psychological disorders, is very complex. In general, individuals with schizophrenia suffer from disturbed perceptions and disorganized thoughts. Their thoughts and perceptions are often extreme, bizarre, and irrational. Schizophrenia is actually a whole category of disorders, so symptoms can be quite different from person to person. However, many people who suffer from schizophrenia cannot function in society without treatment.

General Characteristics of Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is characterized by two general types of symptoms, called positive and negative. Positive symptoms denote the presence of extra and inappropriate behaviors:

- Delusions are false beliefs, particularly about sensations or experiences. Of course, many normal people have false beliefs, and the boundary between a delusion and a “normal wrong belief” is a fuzzy one. The best criterion to tell them apart is the persistence of the belief in the face of contradicting evidence. For example, a woman suffering from schizophrenia who reported that she was Senator Edward Kennedy’s daughter despite the fact that she was quite obviously older than the Senator. Delusions are clearly out of touch with reality.

- Hallucinations are sensations and perceptions that are not based on real stimuli. The most common hallucinations in schizophrenia are auditory, especially hearing voices (two voices conversing are especially common).

- Disorganized speech is speech that quickly and frequently gets derailed or is incoherent.

- Disorganized or Catatonic behavior. Disorganized behavior is is activity inappropriate to the current situation. An individual may react with the wrong emotion (for instance, laugh at bad news), dress bizarrely, or otherwise act in a very unusual way. Catatonic behavior is a failure to react to the environment. Schizophrenic individuals may seem totally unaware of the things going on around them, stand or sit like a statue, or make excessive repetitive movements.

An individual who is currently experiencing positive symptoms is said to be psychotic.

Negative symptoms of schizophrenia are those that represent the loss of normal behavior. They include reduced speech (less fluent, less frequent, empty replies to questions), lack of initiative in activities, and especially loss of emotional characteristics, such as an immobile face or monotone voice. Catatonic behaviors might seem like negative symptoms, but catatonic behaviors are considered positive symptoms because they mark a difference in—and not necessarily a loss of—motor behaviors.

An individual can be diagnosed with schizophrenia if they have two or more of the above symptoms for one month or longer. One of the symptoms must be delusions, hallucinations, or disorganized speech. In addition, some signs of the disorder must be present for at least six months.

A second disorder in this class is delusional disorder, characterized by at least one month of delusions (without a diagnosis of schizophrenia). The individual’s behavior might be more-or-less normal outside of the delusions, making this disorder seem less severe. The delusions can be one of several types:

- Erotomanic: believing that someone loves the individual

- Grandiose: belief that one has great talent or insight

- Jealous: beliefs that spouse or lover is unfaithful

- Perscutory: beliefs that others are spying, cheating, conspiring against, etc.

- Somatic: beliefs about body functions or sensations

negative symptoms: symptoms that represent the loss of normal behavior

positive symptoms: symptoms that represent the presence of extra and inappropriate behaviors

Biological Factors in Schizophrenia

There is strong evidence that schizophrenia has a significant genetic component. The number one risk factor for schizophrenia is having a close relative who suffers from it (Owen & O’Donovan, 2003). Estimates of heritability for schizophrenia by behavior geneticists range from 80% to 85% (Cardno & Gottesman, 2000; Hilker et al., 2018). Remember, even with such a high heritability, having the genes does not guarantee that an individual will develop schizophrenia. For example, if one identical twin has schizophrenia, there is only a 33% to 65% chance that the other twin will also have it.

More than for any other disorder, researchers have discovered severe abnormalities in the structure and activity of the brain associated with schizophrenia. The brains of many people with schizophrenia have larger fluid-filled spaces, called ventricles, than people without the disorder (Lieberman et al. 2001). Because there is fluid where there should be brain tissue, there is a corresponding reduction of brain mass. There are also many individual brain areas that have abnormal activity or structure, including the thalamus, hippocampus, amygdala, and frontal and temporal lobes (Andreasen, 2001) (Module 11). The major functions associated with these brain areas include sensation, memory, emotions, language, and planning, so you can perhaps understand how the many symptoms of schizophrenia occur.

The most important neurotransmitter that has been implicated in schizophrenia is dopamine. There appears to be too much dopamine in some areas of the brain, which may be responsible for the positive symptoms, and too little in areas such as the prefrontal cortex, which may be responsible for the negative symptoms (Conklin & Iacono, 2002; Davis et al., 1991).

Treatments for Schizophrenia

The first line of treatment in cases of schizophrenia is an antipsychotic medication. Traditional antipsychotic drugs decrease the activity of dopamine (that is, they are antagonists), often by blocking the receptor sites on dendrites. These drugs are quite effective for the positive symptoms, but they do not help negative symptoms much. Traditional antipsychotic drugs are very powerful, with serious side effects, such as involuntary facial movements (once these start they are irreversible for most patients), blurred vision, and sexual problems. Without the drugs, however, many people who suffer from schizophrenia have little chance of functioning outside of a hospital. Newer antipsychotic drugs, such as Clozapine and risperdone, have slightly different effects on neurotransmitters (such as blocking only some dopamine receptors or influencing other neurotransmitters such as serotonin), and they appear to be at least as effective as traditional ones with far less serious side effects (Bondolfi et al., 1998).

Although antipsychotic drugs benefit the majority of people who suffer from schizophrenia (Bondolfi et al., 1998; Spaulding et al., 2001), there is definitely a role for other kinds of therapy. In particular, behavior therapy is extremely helpful. A system of reinforcement can help the individual develop needed social skills to help him or her function once the more dramatic positive symptoms have been controlled by medication.

Debrief

- It is extremely likely that you have some false beliefs and that they are resistant to change. How do you know that these false beliefs do not qualify as delusions?

29.3. Personality Disorders and Dissociative Disorders

Activate

- What do you think a sociopath is?

- Have you ever heard of multiple personality disorder? Write down everything you know about this disorder.

When “crazy people” are depicted in movies and fiction, they are often either cold-blooded criminals or “split personalities,” Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde types. These depictions are generally based on two types of psychological disorders: personality disorders and dissociative disorders. Although the truth about people with these sorts of disorders is less dramatic than fictional accounts would have you believe, it is a fascinating and controversial piece of the picture of psychological disorders.

Personality disorders are inflexible patterns of behavior or thinking that reflect deviations from a culture’s expectations and lead to impairment or distress. These are not the temporary lapses in judgment and manners that we all experience at one time or another. Personality disorders are stable over time and across different life situations. There are ten different personality disorders, the most well known of which is antisocial personality disorder.

| Personality Disorder | Key Features |

| Antisocial personality disorder | Disregard for others’ rights |

| Avoidant personality disorder | Socially inhibited, sensitive to negative evaluation |

| Borderline personality disorder | Unstable personal relationships, emotions, and self-image |

| Dependent personality disorder | Excessive need for care from others |

| Histrionic personality disorder | Excessive attention-seeking |

| Narcissistic personality disorder | Grandiosity and lack of empathy |

| Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder | Overly concerned with orderliness and control |

| Paranoid personality disorder | Distrust of others |

| Schizoid personality disorder | Little emotional expression, detached socially |

| Schizotypal personality disorder | Odd behavior, uncomfortable in social relationships, cognitive disturbances |

Dissociative disorders are characterized by dissociation, a split in consciousness. Again, people have dissociation experiences quite commonly. Perhaps when you are preoccupied while driving home, for example, you might arrive home and realize that you do not remember part of the drive. At times, your mind was so focused on your thoughts that you were not conscious of where you were going. That is an ordinary example of dissociation, a simple split in consciousness. People who suffer from dissociative disorders have severe and dramatic splits, however. They lose contact with their identity or memory, and may have feeling of being separated from themselves. As you will see, this last class of disorder is rare (affecting about 1% of the population) and controversial. We will describe the most famous one, dissociative identity disorder in its own short section below.

personality disorder: a category of psychological disorders marked by inflexible patterns of behavior or thinking that reflect deviations from a culture’s expectations and lead to impairment or distress

dissociative disorders: a category of psychological disorders marked by dissociation, a split in consciousness

Antisocial Personality Disorder

Commonly known as sociopaths or psychopaths, people who suffer from antisocial personality disorder have no regard for the rights of other people, happening after reaching age 15 (but can only be diagnosed after 18). Three or more of the following symptoms are required:

- Repeatedly performing illegal acts

- Repeated lying, use of fake names, conning others for personal profit or pleasure

- Impulsivity or failure to plan

- Irritability and aggressiveness

- Disregard for safety of self or others

- Irresponsibility— with work behavior or financial obligations

- Lack of remorse—being indifferent to or rationalizing behavior that hurt others

People with antisocial personality disorder often engage in illegal behavior, deception, aggressiveness, and disregard for others’ safety. They are also typically indifferent about or lack remorse for their behavior. They often lack empathy and are impulsive, arrogant, cynical, and contemptuous toward other people. In addition, alcohol abuse is common among people who have antisocial personality disorder, probably making them even more likely to act on their aggressive impulses (Kraus & Reynolds, 2001).

Antisocial personality disorder is clearly one of the disorders that contribute greatly to the stereotypes about the psychologically disordered being violent and antisocial. By definition, antisocial personality disorder includes illegal, aggressive, or other antisocial behavior, the only disorder to do so. It comes as no surprise, then, that people with antisocial personality disorder are much more likely to commit violent crimes than other people are (Hart & Hare, 1997). Not all people with antisocial personality disorder commit violent crimes, however. Some commit crimes in business, and many are not even criminals at all (Reid, 2001).

Not much is known about the causes and treatments for personality disorders in general, in part because they are difficult to diagnose, a fact that makes them a bit controversial. Antisocial personality disorder is no different. As usual, however, there is evidence for a genetic component for the disorder, but the estimates of heritability have varied widely, ranging from 40% – 70% (Carey & Goldman, 1997; Cloninger & Gottesman, 1987; Torgersen et al., 2012).

Researchers have suspected that some of the biological causes of aggression are important for antisocial personality disorder as well (Module 20). For example, low levels of serotonin, linked to impulsiveness and aggression in normal people, may play a role in antisocial personality disorder (Ferris & de Vries, 1997; Mann et al., 2001). Observers have noted that impulsiveness may be the key characteristic of antisocial personality disorder (Rutter, 1997). This observation has led to the suggestion that SSRI antidepressants be used to treat antisocial personality disorder (Krause & Reynolds, 2001) (see sec 29.3). Although research is lacking for using SSRI’s for antisocial personality disorder, there has been some success at using these drugs to treat patients with other personality disorders and impulse control problems (Hollander, 1999; Markovitz, 2004).

People who have antisocial personality disorder do not have strong physiological reactions to what should be stressful situations (Herpertz et al. 2001). In a situation in which most people would have substantial sympathetic nervous system activity and feel intensely anxious or fearful, a person with antisocial personality disorder might be completely calm. In essence, it looks as if people with antisocial personality disorder do not experience much (if any) fear (Raine, 1997). People with antisocial personality disorder might seek dangerous and antisocial experiences to make up for their lack of internal arousal, and their lack of fear makes it unlikely that they are worried about the negative consequences (Eysenck, 1994).

Although there are definitely characteristic behaviors and patterns of thinking in many people with antisocial personality disorder, suggesting that psychotherapy should be effective, for the most part it has not been. The individuals who have the disorder resist treatment, believing that they do not have a problem—everyone else has the problem (Millon et al., 2000).

Dissociative Identity Disorder

Although dissociative identity disorder is very different from personality disorders, it shares with antisocial personality disorder the unfortunate distinction of being commonly represented in depictions of “homicidal maniacs” in the media. You may know dissociative identity disorder by its former name, multiple personality disorder. It is characterized by a dissociation, or split, between different parts of the personality. The dissociation becomes so complete that the person develops two or more complete personalities; each personality controls the person at different times, and the individual has significant gaps in memory about important events, personal information, or prior trauma. Although schizophrenia and dissociative identity disorder are commonly confused, you should be able to recognize some key differences. In schizophrenia, an individual may have a delusion and believe she is someone else, but she does not exhibit complete, separate personalities at different times.

The cause of dissociative identity disorder is the subject of controversy. Some believe that it results from an individual trying to repress extremely painful memories, especially memories of childhood sexual abuse (Ross, 1997). The child learns to dissociate during the abuse as a way of reducing the distress of the trauma. She (nearly all sufferers of dissociative identity disorder are female) forms a separate personality, one that does not experience the abuse.

Psychologists on the other side of the debate argue that dissociative identity disorder is best explained as an individual’s response to role expectations. More precisely, information from the media, individual beliefs about the disorder, and cues from therapists create a powerful expectation that leads some individuals to develop symptoms of the disorder (Lilienfeld et al., 1999; Spanos, 1994). Perhaps you have just realized why this debate is so explosive. Proponents of the role expectation view have suggested that therapists, in part, cause dissociative identity disorder by using techniques that (unintentionally) encourage the client to form separate personalities. There is in fact evidence that completely normal people can rather easily be encouraged to display symptoms of dissociative identity disorder. All you have to do is hypnotize college students and ask a set of questions designed to “discover” multiple personalities (Spanos et al., 1985).

Also consistent with the idea that dissociative identity disorder is a consequence of some therapy is the observation that it commonly develops only after the therapy. For example, according to one estimate, only 20% of dissociative identity disorder patients had clear symptoms of the disorder before the therapy (Kluft, 1991). Even people who reject the role expectation explanation admit that people who have dissociative identity disorder are commonly unaware of their multiple personalities before therapy (Lilienfeld et al., 1999).

Because of the controversy about the role of therapists in causing this disorder, it is difficult to outline effective treatments for it. For example, therapies that encourage the client to confront the multiple personalities might actually make the disorder worse. As a consequence, dissociative identity disorder is difficult to treat (Ross & Ellason, 1999).

Debrief

- Laypeople are often prone to “diagnose” someone as having a personality disorder, such as antisocial personality disorder. Have you ever done this? Why do you suppose it happens?

- Look over your description of schizophrenia from the Activate exercise for section 29.2. If you have any inaccuracies in it, to what extent did they resemble dissociative identity disorder?

29.4. COVID-19, Quarantines, School Closures and Mental Illness

Activate

- How was your mental health (and that of your friends and family) during the COVID-19 pandemic?

- Do you think that having a mental illness would make it more or less likely that someone might contract COVID-19? How about the reverse? Do you think contracting COVID-19 would make it more or less likely that someone might develop a mental illness?

As a way of wrapping up a general description of mental illness before concluding with some parting thoughts on therapy, let us turn to the most significant set of events in recent memory, the COVID-19 pandemic that began in 2020. You might recall from Module 24 that scientists have been busily producing research related to the pandemic since it began in March 2020. We have already hinted at a bit of what they have discovered. In this section, we will highlight a few more important discoveries. Please keep in mind, that although there has been an explosion of research activity, the topic is still new and as such, we might expect significant modifications of these early conclusions.

There are two types of research findings we would like to focus on:

- General effects of the pandemic and societal responses to it on mental health

- Direct effects of COVID-19 on mental health and of mental health on COVID-19

Then, we will conclude with a brief summary of some psychological factors that are related to behaviors that help and hurt during the active portion of the pandemic.

General effects of the pandemic on mental health

In March 2020, COVID-19 was declared a worldwide pandemic. As a consequence, billions of people across the globe engaged in quarantine-like behavior, while tens of millions contracted COVID-19 and nearly 6.7 million died from the disease (by January 2023).

There is no doubt you were, and probably still are, affected by the pandemic. Perhaps you were one of the billions who participated in a lock-down, shelter-in-place order, quarantine, or a stay-at-home order. During these quarantine-like periods, people who were not infected with or exposed to coronavirus severely limited their contact with people outside of their immediate family and spent a great deal of time in their own home. If you did this, it was hard. (That last statement has been entered into the “understatement of the book” contest.) You also probably experienced some kind of disruption in your education. Further, you may have felt anxiety about you or your loved ones being infected and suffering serious complications or dying. Or perhaps you or your loved ones did contract COVID. What were the effects of all of this uncertainty, loneliness, illness, and death?

Research on the psychology of the pandemic was conducted so rapidly, that several meta-analyses were available even in 2020. For example, Salari et al (2020) reported on 17 separate studies with up to 63,000 participants (depending on the analysis) in the general population in Asia and Europe. These researchers noted that all of the studies reported that individuals suffered many symptoms of mental illness, including:

- emotional distress

- depressed mood

- mood swings

- irritability

- insomnia

- anger

Sound familiar? We thought so, because the key findings were that these symptoms, and other diagnosed mental illnesses were widespread. Some of the specific numbers were

- Stress: 20.6%

- Anxiety: 31.9%

- Depression: 33.7%

And of course, people in the United States did not escape. One study compared 5,065 participants before the pandemic to 1,441 participants in the first month of the pandemic and found that the rate of depression had tripled (Ettman, et al. 2020). Another meta-analysis (this one, international) found a seven-fold increase in depression in just the first two months of the pandemic (Bueno-Notival et al. 2020). As you might guess, having a family member diagnosed with COVID-19 was associated with higher rates of anxiety and depression (this study looked only at college students; Wang et al., 2020). Young adults have been especially devastated. A US national survey conducted in late June 2020 by the CDC found that 62.9% of 18 to 24-year-olds were suffering from anxiety or depressive disorders, 24.7% had started or increased substance use to help cope, and 25.5% had seriously considered suicide (Czeisler MÉ , Lane RI, Petrosky E, et al., 2020). The research also identified that a COVID-19 diagnosis seems to make these problems worse.

Other researchers found that most of the changes in mental health were not permanent. For example, Aknin, et al. (2022) found that distress, anxiety, and depression returned to pre-pandemic levels by the end of the first year of the pandemic. This might sound great, but unfortunately, pre-pandemic levels of distress were quite high. In the US, for example, general distress and poor mental health has been increasing steadily since at least 1990 (Blanchflower and Bryson, 2022). Also unfortunately, rates of suicide (already high before the pandemic) increased during the pandemic, but did not decrease along with anxiety and depression rates during the first year (Aknin et al. 2022).

As researchers continued to examine mental health over the next couple of years, they were able to see some broad patterns. For example, David Blanchflower and Alex Bryson (2022) used US Census data (the detailed surveys that some residents filled out) for over 3,000,000 Americans. They found that poor mental health tracked closely with COVID-19 case rates. In other words, when states and counties had high rates of COVID-19, their residents had poorer mental health. As you might guess, then, when people got vaccinated, their mental health tended to improve. Interestingly, though, that was true for women and college educated men. For non-college educated men, mental health declined if they were vaccinated.

Earlier, we noted that healthcare workers who treat COVID-19 patients were particularly prone to post-traumatic stress disorder. Unfortunately, the risks did not end there. Many also suffered from depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances (Pappa et. al. 2020; a meta-analysis based on 13 studies with 33,000 participants in the first month of the pandemic).

As we reminded you above, you probably had a significant disruption in your own education during the pandemic. As you reflect on your own mental health, let us share what researchers discovered in general. Russell Viner et al. (2022) reviewed 36 individual studies from 11 different countries that examined the association between distress and school closures. These studies examined over 18,000 individual children and adolescents (up to age 19). These studies consistently found that the children and adolescents had worse mental health and well-being when schools were closed. They noted that all of the studies were conducted with the school closures as part of a broader lockdown, so it is impossible to determine the mental health associations with the closures alone. Nevertheless, the authors argued that because school constitutes such a large portion of children’s and adolescents’ days and a major source of their social contacts, these closures may have contributed to distress above the effects of the overall lockdowns.

29.5. Therapy in Sum

Activate

- Think about your images of psychotherapy from your prior exposure to psychology. How would you describe that psychotherapy? What are its characteristics?

Cognitive-behavioral therapy and behavior therapy, which guide clients away from maladaptive patterns of thinking and behaving, are effective treatments for many disorders, including depression, other mood disorders, and anxiety disorders. But they are not the only psychotherapy techniques that clinical psychologists use. Other popular options are psychodynamic therapy and interpersonal therapy, and therapies that combine cognitive-behavioral principles with mindfulness (such as ACT, see below). Another therapy type that is useful to know about is humanistic. The specific therapy used depends in large part on the individual therapist’s training and preference. In an era of managed health care and limited dollars for mental health treatments, however, there is a growing effort to determine which therapies are really most effective in treating particular disorders. We will address that issue after describing psychodynamic therapy and interpersonal therapy, mindfulness-based therapies, and humanistic therapy.

Psychodynamic Therapy

Sigmund Freud’s method of psychoanalysis is no longer much in use in its pure form (Module 19). It has been replaced for the most part by psychodynamic therapy. Although most modern psychodynamic therapists have rejected Freud’s focus on childhood sexuality and his ideas about the role of sexual impulses in everyday life, they do still emphasize that adult maladjustment results from repressed conflicts. The goal of the psychodynamic therapist is to help the client uncover and resolve those conflicts.

The psychodynamic therapist often uses techniques designed to tap into the unconscious, such as free association or dream analysis. In free association, the client is encouraged to say whatever comes to mind. The therapist listens closely for clues that some conflict is lurking under the surface. For example, if the client begins to say something and then quickly changes the subject, the therapist might probe to try to discover if the client was avoiding an unconscious conflict. In addition, the therapist looks for evidence of transference, in which the client reveals unconscious conflicts from the past by transferring those feelings to the therapist. For example, if a client becomes very upset when the therapist slightly criticizes the way he handled a situation at work, it might be because old feelings toward a parent are being transferred to the therapist. Another common tool that some psychodynamic therapists use is projective tests, such as the Rorschach inkblot test. Proponents of these tests believe that aspects of people’s personalities are revealed by the way they interpret the irregularly shaped “ink blots” (or other images) on a series of cards. Most research, however, has found that tests like the Rorschach have poor reliability (Garb, Florio, & Grove, 1998) (see sec 8.1).

In general, little research has been done on the effectiveness of psychodynamic therapies (Wolitzky, 1995). Therapists have had success at treating depression with an offshoot of psychodynamic therapy called interpersonal therapy. This therapy, shorter than traditional psychodynamic therapies (only twelve to sixteen sessions total), focuses on conflicts or problems in current relationships rather than in past ones (Weissman, 1999; Weissman & Markowitz, 2002).

psychodynamic therapy: a type of psychotherapy in which the therapist helps the client uncover and resolve hidden conflicts from the past

free association: a common technique used in psychodynamic therapy, it involves having a client say whatever comes to mind

interpersonal therapy: a modern offshoot of psychodynamic therapy that focuses on conflicts or problems in a client’s current relationships

transference: in psychodynamic therapy, the process in which a client transfers feelings harbored about a person from the past to the therapist

projective test: a psychological test that is purported to reveal aspects of an individual’s personality by the way he or she interprets some ambiguous stimulus

Mindfulness-Based Therapies

Mindfulness is a way to train an individual to focus awareness in such a way that troubling thoughts are observed almost as an outsider and without judgment. It is traditionally used in a mediation setting, and the principles of mindfulness (non-judging, non-reactivity, and observation, for example), have made it into several specific therapy techniques. For example, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy encourages clients to accept negative and troubling thoughts, and is used commonly to treat depression and anxiety disorders. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy explicitly combines ideas from cognitive therapy with mindfulness meditation and has strong support as a treatment for depression.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: encourages clients to accept negative and troubling thoughts

Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy: a therapy that explicitly combines ideas from cognitive therapy with mindfulness meditation

Humanistic Therapy

Humanistic therapies start from the assumption that people have a basic orientation toward growth—that is, to reach their full potential. When they are maladjusted, it is because some barrier is preventing them from going in their natural direction. The therapist’s main role is to help clients to find the ability to solve their problems within themselves.

The most well-known humanistic therapy, called client-centered therapy; was developed by psychologist Carl Rogers (1951). In client-centered therapy, the therapist uses three key tools in his or her role as a facilitator, someone who helps clients realize that they can, in fact, solve their own problems. The first is unconditional positive regard. The therapist listens and accepts what the client says without judging. Second, the therapist exhibits genuineness, sharing his or her thoughts openly and honestly. Third, the therapist employs empathetic understanding. Throughout the therapy, a client-centered therapist uses active listening, a technique of restating, paraphrasing, and clarifying what is heard without judging it. Although few modern therapies identify with the humanistic label, many do make use of techniques like active listening.

active listening: a technique of restating, paraphrasing, and clarifying what is heard without judging it

humanistic therapies: a type of psychological therapy that assumes that people have a basic orientation toward growth; the therapist’s main role is to help clients to find the ability to solve their problems within themselves

client-centered therapy: a humanistic therapy developed by Carl Rogers. It uses unconditional positive regard, genuineness, and empathetic understanding

Can an App Provide Therapy?

From 19th century psychoanalysis on Sigmund Freud’s couch to the present, psychotherapy has been a face-to-face interaction with a human therapist and a human patient or group (although there is animal behavior therapy for dogs). Artificial intelligence, in which computer programs learn and perform complex tasks that used to be possible for humans only, has begun to make contributions to medical care, such as diagnosis. It seems at least possible that a computer program might be able to provide some of the benefits of psychotherapy as well.

You might be interested to know that one of the earliest famous demonstrations of artificial intelligence was a program called ELIZA. If you have an iPhone, ask Siri, “Who is ELIZA?” One of the answers Siri gives (there are a few different ones) is: “ELIZA is my good friend. She was a brilliant psychiatrist, but she’s retired now.” ELIZA was a computer program developed by Joseph Weizenbaum around 1965. It was designed to mimic a humanistic therapist. In reality, ELIZA simply had a series of canned responses to keywords (for example, if you said something with the word “no,” ELIZA usually responded with “You are being a bit negative.” Even so, some observers believed that ELIZA was actually able to understand them, and reported some therapeutic benefit of talking to her (of course, “talking” meant typing). Even some practicing psychiatrists thought that ELIZA showed promise as an actual therapist (Weizenbaum, 1966; 1976)

Click here for a pretty good implementation of ELIZA (very low production value, though).

Were these 1960’s psychiatrists onto something? Can a computer program provide psychotherapy? Because computer-based, or smartphone app-based, therapy is quite new itself, you might realize that research into its effectiveness is just beginning to accumulate. For example, one group of researchers examined 555 different apps that are promoted in the treatment of PTSD (Sander et al. 2020). Only 69 followed principles from current therapy methods—most were based on CBT methods. Only one was evaluated in an experimental study. It was a small study, but it did show informal results (on outcomes such as adhering to treatment requirements, and usage of different elements of the program) similar to participants who received traditional CBT. So, in this case, the results showed that the apps have the potential to be an effective part of treatment, but we are still too early to know how effective.

The results are similar for other apps and other disorders, as well. Wang, Fagan, and Yu (2020) examined 28 apps for treating depression, and found only five that had research support. Again, studies tended to be small, and the results limited (for example, several studies showed immediate effects but did not do any follow-up assessments). Again, at this point, we would have to conclude that app-based therapy shows promise, but the evidence for their widespread adoption is not there yet.

Common Factors in Therapy

Although we have focused on the differences between therapies, the truth is they share a lot in common. And research has generally found only modest differences in effectiveness between different therapy styles (Cuijpers, et al., 2008). If you are interested, Division 12 of the American Psychological Association is devoted to Clinical Psychology. They offer a terrific resource of 86 different therapy-disorder combinations, and the level of research support for each. For example, Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Depression has strong research support; Psychoanalytic Treatment for Panic Disorder is listed as modest support/controversial.

At least 40 of the 86 are CBT or another cognitive- or behavioral-based therapy. They all have strong, or at least, modest research support. The number, 40, is also important, though, because it suggests that treatments based on cognitive and behavioral principles have been subjected to the most research. That is another point in favor of CBT, exposure therapies like systematic desensitization, and ACT. But again, the differences in effectiveness across therapies tends to be modest. One reason is probably that therapies, regardless of their specific orientation, often have important factors in common:

- Any successful therapy provides a client with a new way of looking at a previously unsolvable problem. One of the difficulties of solving real-world problems is that we get stuck representing or defining them incorrectly, a pattern of thinking called fixation (Module 7).

- Before beginning therapy, people commonly avoid their negative thoughts and emotions because of the distress they cause. As therapy clients, they will be forced to face those thoughts and emotions, and over time they can become less threatening. In essence, any therapy provides a desensitizing effect, working much like systematic desensitization does for anxiety (Garfield, 1992).

- Perhaps the most important shared factor across successful therapies is the trusting and caring relationship that develops between the therapist and client (Blatt et al. 1996; Teyber & McClure, 2000). Just as you may benefit most from advice when it is sincerely given by an individual whom you like, trust, and respect, therapy administered the same way tends to be effective.

It is likely that these shared factors will lead to a degree of success for very many competently administered therapies (Messer & Wampold, 2003; Wampold, 2001). However, we would caution you against relying on therapies that have not been demonstrated through research to be effective.

Debrief

- To what extent did your image of psychotherapy resemble psychodynamic or client-centered therapy? Why do you think these images are more common than those of cognitive-behavioral therapies?

- Which of the “shared factors” of therapy can you recognize in problem-solving or advising situations in your own life?