4 The Science of Psychology: Tension and Conflict in a Dynamic Discipline

READING WITH PURPOSE

Remember and Understand

By reading and studying Module 4, you should be able to remember and describe:

- Three different kinds of disagreements that occur in psychology

- The relationship between the amount of tension in a field and important outcomes

- The origins of psychology

- Disagreements about theories: free will versus determinism, nature versus nurture (René Descartes and John Locke), people are good versus people are bad (René Descartes and Thomas Hobbes)

- Disagreements about scientific and non-scientific psychology (Wilhelm Wundt, William James, and the behaviorists)

- Disagreements about basic and applied goals in research

Analyze, Evaluate, and Create

By reading and thinking about Module 4, participating in classroom activities, and completing out-of-class assignments, you should be able to:

- State and defend your position on the three debates about fundamental theories

- State and defend your position on the relative values of scientific and non-scientific psychology

- State and defend your position on the importance of basic and applied research

Throughout the first three modules, we have emphasized the importance of a scientific approach to provide a solid foundation to our house of psychology. Honestly, this is one of the most important points in the book, so we certainly want you to remember it. And it is also essential that you remember and understand the formal principles that underlie science’s value (from Module 1) and the formal methods that we use in scientific psychology (from Module 2). There is another component to a scientific approach, however, and it is more of an informal component. The final module of each unit of this textbook (Modules 4, 9, 14, 18, 24, and 30) will introduce you to some of that informal component. Think of it as a more everyday description of how scientific psychologists actually work: for example, how they interact with each other, how they choose topics to research, and so on. (These unit-ending modules will also focus on the different sub-fields to help you fit them into our house metaphor, but that will not really start until Unit 2).

Let us begin this informal view of scientific endeavors by considering some important issues related to how scientists interact with each other. To do that, we will need to take you through some history of psychology (and philosophy). This historical view will be a common approach we will take in these unit-ending modules.

Imagine three potential friends or romantic partners. One person agrees with everything you say. Most of you will find a relationship with someone like that somewhat boring. On the other hand, a potential partner or friend who disagrees with everything you say, often aggressively, would lead to a relationship that is too stormy and distressing to be fulfilling. An ideal relationship would be with someone in between these two extremes, someone with whom you have “spirited disagreements,” serious yet respectful discussions about issues that you both care about. We propose that this third imaginary relationship serves as a useful analogy for the types of interactions that should characterize a dynamic, evolving discipline such as psychology.

Throughout this unit, we have invited you to “think like a psychologist,” as if all psychologists think alike. One important goal of this module is to explain that psychologists do not all think alike. Psychologists throughout the history of the discipline have disagreed often. Here we will describe three basic kinds of disagreements that characterize the field of psychology.

- Disagreements about the best theoretical explanations for fundamental observations about the human condition

- Disagreements about the role of science and scientific methods of inquiry in the discipline

- Disagreements about the relative importance of two goals: discovering basic principles of human behavior and mental processes versus applying this knowledge to help people

Although psychologists do not always see eye-to-eye, the lack of agreement is not necessarily a problem. If managed successfully, disagreement, conflict, and tension in a discipline are essential for scientific progress.

Tension Is Good

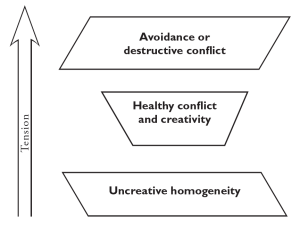

Like that ideal imaginary romantic partner, the field of psychology has just the right amount of conflict and tension to keep things lively and interesting. There is tension in psychology as different camps of psychologists champion their favored theories and visions of the field. If there is too much tension, psychology would be too disjointed to hang together as a discipline. If there is too little tension, psychology would become too homogenized, too uniform, to be creative and dynamic.

Psychological research about people has left no doubt that extreme conflict or poorly managed conflict is very damaging and can ultimately lead to anger, pain, sadness, animosity, and even violence (Johnson, 2000). Any of these destructive outcomes can lead people to avoid one another. To be sure, occasional avoidance to manage particular conflicts has its place. If you are primarily interested in maintaining a relationship, for example, avoiding conflict may be a very appropriate temporary strategy (Johnson, 2000). This strategy is particularly common in cultures that value relationships highly, such as China (Tjosvold and Sun, 2002). As a general strategy, however, avoidance is often counterproductive or even unhealthy (De Dreu et al., 2000). When people (or disciplines) that could enrich each other’s understanding act instead as if neither has anything to offer, both suffer.

Too little conflict can be nearly as damaging as too much, however. Research in education and work organizations has indicated that conflict can lead to creativity and good decision-making (Cosier and Dalton, 1990; James et al., 1992). The key is to manage conflict so that it does not fall into unproductive infighting (Johnson and Johnson, 2003).

Although these observations about conflict and creativity have been made through research on small groups or in individual organizations, it is reasonable to expect that they would apply to a discipline like psychology as well. After all, as you will see, psychology is a collection of factions with different points of view and opinions.

Figure 4.1: Tension in the Field of Psychology

Psychology’s Long History of Tension and Conflict

The birth of scientific psychology is often taken to be 1879. What happened that year is that Wilhelm Wundt established the first psychological laboratory in Leipzig, Germany, supporting the idea that psychology is a scientific discipline. It was not really the birth of the discipline, though. The term psychology had already been in use for over 300 years, and several researchers across Europe had already been working in areas that would become part of psychology. But because Wundt established the lab, and he worked hard to establish psychology as a discipline throughout Europe, he is given the credit (Hunt, 2007).

The term psychology first appeared in 1520, but systematic thinking about human behavior and mental processes began far before then. Morton Hunt (2007) places the real beginning around 600 BC. Prior to that date, people simply assumed without question that human thoughts and emotions were implanted by gods. The real birth of psychology was probably the day that philosophers started to question that belief.

Hunt notes that the questions asked by the ancient Greek philosophers became the fundamental debates of psychology, debates that in many cases continue in some form even today. Thus, the great philosophical disagreements from centuries ago became the subject matter and controversies of psychology. We can see many of these philosophical disagreements at the root of some of the most fundamental conflicts in the history of psychology: conflicts about fundamental theories of human nature, methods of inquiry, and proper goals for psychologists.

Conflicts About Fundamental Theories

Scientific meetings are filled with people who disagree with one another. If a psychologist is giving a presentation about a theoretical explanation for depression at one of the meetings, for example, they can be sure that some members of the audience are there precisely because they disagree with the presenter. Occasionally, tempers flare and interpersonal conflict, not just scientific conflict, is part of the picture. One of the authors once witnessed an audience member purposely sit in the front row of a presentation given by a researcher he did not like just so he could cause a commotion when he got up in the middle and walked out.

Particular psychologists may have invested a great deal in a specific theory. They may have devoted many years to developing it, and they may have based their entire professional reputation on the success of the theory. In these cases, it can be difficult to avoid seeing an attack on your theory as a personal attack. Making matters worse, some attacks on theories are more personal than they should be. Robert Sternberg, a former president of the American Psychological Association, has noted with dismay the sometimes savage criticism that may be leveled against rivals, far harsher than is warranted by disagreements about theories. Yet interpersonal conflicts are somewhat unusual. Instead, psychologists tend to have the healthier “spirited disagreements” that are confined to the theories alone.

Quite likely, no psychological theory is universally accepted across the discipline. But that lack of agreement can be a good thing. Progress in science occurs through the production and resolution of scientific controversies, and psychology is no different (see Module 1). Sometimes the disagreements are minor, focusing on a small part of a single theory. At other times the disagreements are related to very important theories or reflect fundamental beliefs about the human condition.

Conflicts about human nature have been part of many major theoretical disagreements in psychology. Let us consider three of the theory-related disagreements. Keep in mind that the conflicts are larger than disagreements about individual theories. They address basic philosophical beliefs about the nature of humanity. These disagreements had their origin in philosophy and thus illustrate our earlier point about the development of psychology from earlier philosophical debates. Some of the details about these conflicts are filled in throughout the rest of the book.

Free Will Versus Determinism.

For many centuries prior to the 6th century BC, the questions about our mental processes and behaviors had a very simple answer: Everything was predetermined by a god or gods. The ancient Greek philosophers began to question this belief when they proposed that emotions and thoughts were not placed in the head by gods, that at least some of them came from an individual’s experience and from thinking about the world (Hunt, 2007). By asking questions such as “Does the mind rule emotions, or do emotions rule the mind?” some of these philosophers began to wonder whether human beings had free will.

When psychology emerged, it also adopted the free will versus determinism debate. For example, a group of psychologists known as the behaviorists were champions of a deterministic view. Prominent behaviorists in the 1940s and 1950s, such as B. F. Skinner, contended that human behavior was entirely determined by the environment. For example, behaviors that are rewarded persist, and those that are punished fade away. In the 1960s several groups of psychologists rejected this overly deterministic stance. For example, cognitive psychologists noted that human behavior was far too complex and novel to have emerged as a simple response to the environment. (sec Module 9)

Nature Versus Nurture.

René Descartes, considered by many to be the father of modern philosophy, championed a viewpoint called rationalism; he believed that much of human knowledge originates within a person and can be activated through reasoning. Hence, knowledge is innate, a product of nature only (1637). John Locke is perhaps the most famous philosopher on the other side of this debate; his viewpoint is typically referred to as empiricism. He likened the mind to white paper (or a blank slate); through experience (or nurture) the paper acquires the materials of knowledge and reason (1693). Although Locke and Descartes did not have conflicts themselves—Locke was only 22 when Descartes died—Locke’s writing did take aim at Descartes’s specific ideas (Watson, 1979).

A very controversial book was published in 1994 that reignited the nature versus nurture debate. In The Bell Curve, Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray argued that because the genetic contribution to intelligence is so high within a population, social interventions are unlikely to help people with low intelligence. To restate the point simplistically (although the authors were careful not to state this outright), nature is more important than nurture. Many psychologists stepped up and pointed out the errors in research and reasoning that led Herrnstein and Murray to these conclusions.

And these conflicts continue today. In 2018, behavioral genetics researcher Robert Plomin published Blueprint: How DNA Makes Us Who We Are. Plomin argued, based on research over the past 50 years, much of it conducted by Plomin himself, that much of what we consider as important aspects of nurture, such as parenting styles, do not affect outcomes very much. Critics were quick to jump in and do exactly what they are supposed to: argue for the other side. For example, Richardson and Joseph (2019) contended that Plomin’s explanations glossed over subtle factors related to nurture that temper his conclusions and that his analyses minimized the changes that occur in people during their lifetimes, something that a genetics-only approach has difficulty explaining. We are not coming down on one side or the other in this debate, as it is still in progress. It is, however, a terrific example of a conflict from philosophy that continues today in scientific psychology.

People Are Good Versus People Are Bad.

Thomas Hobbes, a contemporary of Descartes, is considered by many to be the father of modern political science. He believed that a strong monarch was necessary to control the populace because people had a natural tendency toward warfare. Without a strong leader, Hobbes believed, the lives of men were doomed to be “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short” (1651). In other words, people are bad, or at least seriously flawed. René Descartes figures prominently on the other side of this debate. He believed that the innate knowledge that we derive through reason comes from God. Thus human beings are fundamentally good.

Throughout the history of psychology, this debate has resurfaced repeatedly. For example, Sigmund Freud believed that our personality emerges as we try to restrain our hidden, unacceptable desires. (see Module 19) A group called the humanistic psychologists arose in the 1960s as a reaction against the view of people as bad and in need of restraint. (sec Mod 25)

Conflict About Methods of Inquiry: Science Versus Non-Science

As we told you in Module 1, psychology is a science. Or is it? Many people outside of psychology do not consider it a science. Scientific psychologists tend to find this belief quite bothersome, but this conflict was very important for the development of psychology into the discipline that it is today.

The ancient philosophers Socrates and Aristotle, both of whom greatly influenced the discipline of psychology, foreshadowed the difference between science and non-science. One of Socrates’ most famous quotations is “An unexamined life is not worth living.” He favored a very introspective (non-empirical, or non-scientific) approach to understanding human nature. Aristotle’s thinking, on the other hand, was guided by empirical observations of the world around him. On the basis of these observations, he formulated theories about memory, learning, perception, personality, motivation, and emotion (Hunt, 2007).

During the infancy of psychology, the early giants in the field frequently disagreed about what the appropriate subject matter of psychology is and, by implication, whether the field is scientific or not. Recall Wilhelm Wundt, who in 1879 established the first psychological laboratory. One of Wundt’s central goals was the reduction of conscious experience into basic sensations and feelings (Hunt, 2007). Wundt’s research relied on the key method known as introspection. Trained observers (often the researchers themselves) reported on their own consciousness of basic sensations while they completed tasks such as comparing weights or responding to a sound. Wundt believed that these experimental methods could be applied to immediate experience only. Recall that science requires objective observation. Wundt believed that mental processes beyond simple sensations—for example, memory and thoughts—depended too much on the individual’s interpretation to be observed objectively. Hence to him only part of what we now think of as psychology could be a true science.

The early 20th century brought several challenges to Wundt’s approach. Some psychologists began to broaden the concept of introspection. For example, in the United States, William James embraced a more expansive and personal type of introspection, in which naturally occurring thoughts and feelings, not just sensations, were examined. He believed that this method was a great way to discover psychological truths. Although James’s more inclusive definition of introspection greatly broadened the scope of psychological inquiry, this expansion made it very difficult to assert that psychology was a scientific discipline. As you might guess, different observers might very well report different observations while introspecting about the same task. That is, because introspection was subjective and unreliable, it was a poor method on which to base a new science.

By far, however, the most significant challenge to Wundt came from the early behaviorists. They sought not to expand psychology but to reduce its scope, and in so doing, they rejected virtually all of the previous efforts in psychology. John B. Watson, a young American psychologist, was the chief spokesperson for the behaviorist movement. He defined psychology as the science of behavior and declared that the goal of psychology was the prediction and control of behavior. Watson emphasized that a psychology based on introspection was subjective; different psychologists could not even agree about the definitions of key concepts, let alone examine them systematically. In short, the introspective method was not useful. Further, mental states and consciousness were not the appropriate subject matter of psychology, defined as the science of behavior. The questions that had been addressed by introspective psychology were far too speculative to be of scientific value (1913; quoted in R. I. Watson, 1979).

Watson produced an extremely persuasive case for why behaviorism was right and all previous psychology was wrong. Although he was not the first to make many of these points, he was, in essence, a top-notch salesperson and his rather narrow vision of psychology eventually took over a great deal of the field (Hunt, 2007).

In the 1950s the cognitive revolution shook psychology, as internal mental processes became acceptable topics of study. (sec Module 9) This time, however, researchers were careful to approach these topics scientifically.

Today, the field of psychology combines the scientific orientation of Wundt and the behaviorists with the broad view of the scope of the psychology of William James and the cognitive psychologists. It seems rather unlikely that these two visions would both be represented in modern psychology if they had not been so vigorously championed by the two camps during the discipline’s early history.

Some might argue that, because the field has successfully merged the interests of earlier non-scientific psychologists with the scientific approach, the non-scientific orientation to psychology is no longer necessary. In other words, they believe that psychology should be purely scientific. The problem with this view is that it ignores an important lesson from the history of psychology. Basically, how do we know that non-scientific psychology can no longer be useful? If in the past non-scientific ideas merged with scientific methods to expand the useful scope of psychology, why should we be content to stop mixing things up now? In short, today’s non-scientific psychology may be a useful source of topics and ideas that future researchers may bring into the scientific fold.

The development from humanistic psychology into positive psychology is a great example of how conflict about methods of inquiry continues—and continues to make psychology ever more useful. In the 1950s and 1960s a group of non-scientific psychologists—for example, Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow—publicly stated their belief that human beings are individuals who have a natural tendency toward growth and self-fulfillment. They also largely rejected the scientific approach. Partly because of this disdain for science, the original humanistic psychology has little influence in modern psychology. Instead, a new sub-sub-field known as positive psychology has emerged from it. The positive psychologists have many of the same goals and basic beliefs as the former humanistic psychologists, but instead of rejecting the scientific approach, they have embraced it. Basically, positive psychology focuses on “mental health rather than mental illness” (Weil, quoted in Seligman, 2002). Positive psychology has already contributed a great deal to our understanding of what leads to happiness, health, and fulfillment (Diener, Oishi, Tay, 2020).

Conflict About Proper Goals: Research Versus Application.

People who work in a discipline like psychology can have two different types of goals. They can devote themselves to advancing knowledge in the discipline, or they can devote themselves to using the discipline to solve problems. Those who do the former are concerned with basic research. The others are interested in application. When researchers conduct research in order to solve specific problems, they are said to be involved in applied research.

Non-scientific psychologists tend to be application-oriented; scientific psychologists may be basic researchers or applied researchers. Throughout the history of psychology, both basic research and applied research have contributed to the development of the field. Basic research has built most of the knowledge base of psychology, while applied researchers have solved problems for government and business or on behalf of people who suffer from behavioral or mental problems. Practicing psychologists do not typically conduct research at all but have been concerned with using psychological knowledge to help people.

There has often been tension between basic researchers and application-oriented psychologists. The two sides are often pitted against each other. The pool of available research funds is a fixed, or even shrinking, pie. That means that if funding organizations decide to throw support behind applied research, basic research will suffer. And vice versa. Observers note that this is just what has happened over the past 40 years or so.

Probably in part because of the competition for resources between basic and applied research, psychology has sometimes not been successful at harnessing the power of the tension between the two sides to create healthy conflict. In the not-too-distant past, Ph.D. students who pursued careers in applied, invariably higher-paying areas were considered “selling out” by many basic researchers. Others often referred to basic research as “pure” research, as if applied research was somehow “impure” or “dirty.”

The general public has a role in this tension, by the way. The public has a tendency to belittle basic research. People often do not understand the point of research that cannot be put to use immediately. Politicians can sometimes fuel the criticism. Former U.S. Senator William Proxmire was well-known for the Golden Fleece Award that he publicized during the 1970s and 1980s. This “award” highlighted and ridiculed activities by government agencies that, in Senator Proxmire’s opinion, were a waste of taxpayers’ money. Although he criticized what he saw as waste throughout the government, basic research was a frequent target. His very first Golden Fleece Award was for research on why people fall in love (see Module 22).

Many people do not realize that basic research is an investment in the future. Like any investment, a particular research project might not turn out to be useful right away. But the eventual payout may be enormous. For example, consider research about genetics. Basic research on genetics began in the 19th century and has continued since then. Over the years, we have discovered many applications of this knowledge, such as the genetic contribution to physical and psychological disorders. As we continue to expand our knowledge of how genes work, we may someday be able to cure many currently incurable diseases.

The problem is, how do you know which basic research that is being conducted today will allow us to solve important problems 10, 20, or 30 years from now? For example, who can tell whether research about environmental factors in human aggression (another “winner” of a Golden Fleece Award) may or may not someday be used to end human aggression? To ridicule basic research today is shortsighted and uninformed.

Another concrete example of how basic research may pay off in the long run concerns a 1979 winner of the Golden Fleece Award, research on the behavioral factors in vegetarianism. At the time, the U.S. government was dispensing the advice that people should eat from the “four basic food groups”—roughly, that people should eat equal amounts of meats, dairy products, grains, and fruits and vegetables. Since 1979 there has been a dramatic change in that advice; people are now advised to eat large amounts of grains and fruits and vegetables and relatively small amounts of dairy products and meats (the USDA Food Pyramid). Most people eat nowhere near enough fruits, vegetables, and grains. In short, a vegetarian diet is a much healthier diet than most Americans currently eat. The behavioral factors in vegetarianism would be a pretty useful piece of information to know now, wouldn’t it?

Very simply, there is a tradeoff between basic research and applied research. With any individual basic research study, there is a small chance that you will be able to solve a very important problem at some point in the future. With applied research, there is a good chance that you will be able to solve a less important problem soon. Rather than choose one over the other, we would like to see both valued.

The truth is, basic researchers and applied researchers need each other. When basic researchers remove themselves too much from the real world, their research may become so artificial that it distorts the way processes actually work. When applied researchers overlook the findings of basic research, they work inefficiently, examining many dead ends or “reinventing the wheel” by repeatedly demonstrating well-established phenomena. There will probably always be some friction between basic and applied researchers, however. Basic researchers may continue to covet the resources available to applied researchers, while applied researchers may continue to long for the intellectual respect accorded to basic researchers.

There is reason to believe that the separation and unhealthy tension of the past will diminish, however. In fact, the line between basic and applied research seems to be blurring these days. Basic researchers, funded by organizations that need to justify their existence, are being encouraged to propose applications of their research. Applied researchers are being encouraged to keep an eye on developments in basic research so they can more efficiently solve the human problems they encounter. The history of psychology has demonstrated that basic research is more accurate and comprehensive when it pays attention to the real world and that application is more effective when it is grounded in basic research results.

The Perils of Too Little Conflict: The Replication Crisis

You might recall (in fact, we hope you recall) that replication is one of the defining features of science. Only when multiple researchers have been able to successfully produce an effect can we begin to have confidence that the effect is reliable (think, real). The road to reaching this conclusion is, or should be, filled with the kind of conflict and tension that leads to scientific progress. Unfortunately, the field of psychology has discovered in the past few years that we have a problem in this area. For a long time, researchers paid little attention to the need for replication. In 2015, the Open Science Collaboration project reported on the results of an attempt to determine how serious this lack of attention is. The project replicated 100 studies that had been published in three prestigious psychology journals in 2008. Their results were sobering. Overall, only 39% of the statistically significant results reported in the original articles were reproduced upon replication.

Now, before everyone panics and drops psychology to take a “real science course,” this does not mean that nearly 2/3 of the published studies were wrong. But it almost certainly means that some of them are wrong. For a given non-replicated study, we now have a legitimate scientific controversy on our hands. One set of researchers has found one result, and a second set has found another. We need a third, fourth, fifth (and so on) set of researchers to come along and settle the controversy. We certainly hope that this sounds familiar, as it is exactly how science is supposed to work. Yes, real science. The process in psychology will just be a bit faster over the next few years while we try to get caught up. So although the “replication crisis” as the problem became known is a significant issue, it is one that can definitely be addressed. Stay tuned below for some additional specific steps the field is taking to prevent a recurrence of the problem.

How did we get here?

You might wonder how the field got into this problem. It is an oversimplification to blame it completely on a lack of conflict, leading to misplaced trust in individual research results. Actually, the causes are complex, and it is worth going into a little bit of detail about two of the major factors. One factor explains why no one bothered to do replications, and the second explains how researchers might get “wrong” results to begin with (thus making those missing replications essential).

Factor Number 1: There was no incentive structure in place to encourage replications.

The large majority of research in psychology is conducted by professors at Universities across the world. Although you may know your professors as teachers, many professors are employed more for their research than their teaching. (Note, this is not to say that they don’t care about or are not good at teaching, just that the job of a university professor is, to a large degree, based on research). In order to keep their jobs at their universities, these professors have to publish original research. A beginning professor who published replications would literally be out of a job when tenure decisions are made. Making matters worse, many psychology journals over the years did not consider replication studies worthy of publication. So very few researchers did them.

Factor Number 2: Publication bias in favor of positive results, leading to the file drawer effect and questionable research practices.

Scientific journal articles in psychology (and other disciplines) have another bias in addition to an aversion to replications. They also have a strong preference for studies that work, or in other words, that obtain statistically significant results. This preference is so strong, that many researchers who obtained results that were not statistically significant abandoned the projects. They didn’t throw the results away, they just filed them away; this phenomenon became known as the file drawer effect (years ago, the results were stored in physical file cabinets; nowadays, the results are just stored in a forgotten folder on a researcher’s computer). The basic idea is that for any published study that shows statistically significant results, we have no idea how many other researchers have non-significant results lurking unseen in their file drawers.

Making matters worse, because researchers’ livelihoods literally depended on publishing statistically significant results, they felt intense pressure to produce those results. As a result, many researchers began to adopt what became known as questionable research practices. Please note that we are not saying the researchers were being dishonest (although some certainly were). Rather, it became routine for researchers to inadvertently adopt techniques that were likely to produce “false positive” research results. A full description of the kinds of questionable practices that were common is beyond the scope of this textbook, so we will describe only one (if you are interested in learning more, we recommend you take courses in Statistics and Research Methods). One of the key questionable research practices is known as p-hacking. A p-value is a statistical concept that signifies that a research result is statistically significant. In the most basic form of p-hacking, a researcher would produce a great many research results, and select only those that the p-value indicated were statistically significant.

How do we get out of here? Honestly, psychology has made a lot of progress already. The field has identified some research results that might be ready to be removed from textbooks (and we will mention some of these throughout the book, in case you encounter them elsewhere). More importantly, however, researchers have begun to embrace Open Science practices, which will make it easier for future researchers to conduct replications and less likely that research based on questionable practices will sneak through the journal article review process. Open Science practices include three key parts (APS, 2020):

- Open Materials. Researchers make their materials freely available to other researchers to facilitate replications.

- Open Data. Researchers make their original data freely available so that other researchers can run their own statistical analyses to ensure that the original findings were not dependent on the specific data analysis choices.

- Preregistration. Researchers publicly commit to methods and data analysis strategy for a specific study prior to conducting it to prevent many questionable research practices from occurring.

One other practice that has been instrumental in recovering from the replication crisis is the use of meta-analyses. A meta-analysis is a study of studies, so to speak. Researchers take multiple studies on a topic and combine them into a single dataset, as if they have one giant study. Then, they perform advanced statistical analysis to allow them to conclude if a research result is stable beyond a single study. Meta-analyses are also useful for estimating the size of an effect and for determining factors that might change an observed effect. Obviously, meta-analyses are very useful, but they do not answer every question. For one, researchers cannot (or do not) always include all of the studies in an area. The exclusion criteria that they use (and sometimes, the specific data analysis procedure) can sometimes change the conclusions. Especially important is the need to find unpublished work in a research area to include in a meta-analysis to overcome the problem of publication bias.

By now the field has seen quite a few attempts to replicate individual studies, many meta-analyses, as well as several large-scale organized attempts to replicate many studies at one time (e.g., the Many Labs efforts). As a general rule of thumb, it appears that approximately half of the results of published studies can be reproduced. Again, this does not mean that half of what you are reading in your textbook is wrong, but it does mean that the ongoing process of self-correction is still going on (after all, that is what ongoing means).

Oh, and one last point. Psychology is not the only science that is enduring a replication problem. Even a quick Google search will reveal that among other disciplines, economics, exercise and sports science, and even biomedical research are all dealing with similar issues. Yes, biomedical research.