9.8 Posterior and Lateral Thorax: Inspection

Ensure the client is positioned in the best way to assess the lungs: usually seated or in the high Fowler’s position with the client looking straight ahead so that the lungs can fully expand. If you are assessing a young child or newborn, you could ask someone (e.g., care partner, health care provider, parent) to help hold the client upright on the exam table or sit the client in their lap while assessing the respiratory system.

You should help the client into the side-lying position if they are in a supine position and cannot sit upright. This repositioning may require the help of another health care provider if the client is unable to roll over themselves.

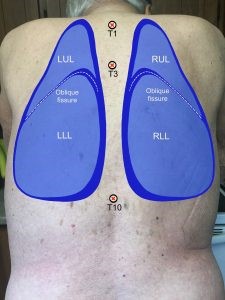

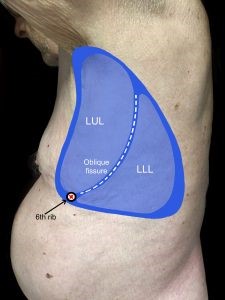

Assessment of the posterior and lateral thorax involves assessing from the shoulders and the axillary area down to the bottom of the rib cage. To help visualize, see Figure 9.9a for the location of the lobes on the posterior thorax and Figures 9.9b and 9.9c for the location of the lobes on the lateral thorax (shown upon inspiration).

Keep in mind, you should do the entire assessment on the bare skin.

Step 1: Inspect for symmetry of thorax and chest expansion.

- Compare the left and right sides of the thorax. Are the shoulders, scapula, and ribs symmetrical upon observation? Does the chest appear elliptical in shape? (Barrel shape indicates a chronic respiratory condition as commonly seen in COPD patients)

- When the client breathes, do the left and right sides of the thorax expand and recoil symmetrically? Make a note if the expansion is asymmetrical (one side has limited expansion, lags in expansion, or does not expand). This can happen when one lung cannot expand due to conditions that involve inflammation and air between the lungs and chest wall (i.e., pneumothorax) or partial or complete collapse of the alveoli (i.e., atelectasis). You may also notice that in pregnant women, the thorax shortens while the costal angle widens to accommodate the enlarging uterus: this is normal.

Step 2: Inspect the spinous process, ribs, deformities, masses, and swelling.

- Do the spinous processes appear in a straight line down the vertebral line of the posterior thorax?

- Are the ribs sloping downwards?

- Do you observe any deformities, masses, or swelling?

Step 3: Inspect skin color, skin integrity, and lesions

- Is the skin color consistent across the posterior and lateral thorax?

- Do you notice any skin discoloration? Is the skin intact? Are there any lesions?

- Do you notice any scars? If so, ask the client the cause. For example, a client may have a scar from lung surgery such as a lobectomy, and this surgery can lead to no air entry when you auscultate the lungs.

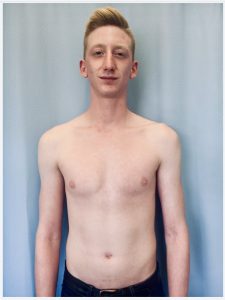

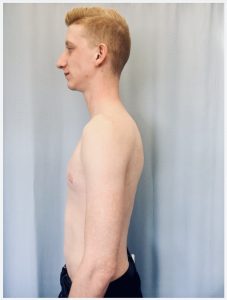

Step 4: Inspect the anteroposterior to transverse diameter of the thorax. See Figure 9.10. The transverse diameter is shown in the first image across the chest. The anteroposterior diameter is shown in the second image from front to back. In most adults, the anteroposterior to transverse diameter ratio is about 1:2.

- The ratio will be closer to equal (1:1) when a client has conditions that give rise to hyperinflated lungs (e.g., emphysema). Also, a 1:1 ratio is usually present in children younger than two years of age.

Figure 9.10: Anteroposterior to transverse diameter. From Introduction to Health Assessment for the Nursing Professional (2024), licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Step 5: Note the findings.

- Normal findings might be documented as: “Symmetrical posterior thorax with symmetrical chest expansion, no thorax deformities or masses, spinous process in a straight line, no skin discoloration, anteroposterior to transverse diameter 1:2.”

- Abnormal findings might be documented as: “Horizontal ribs with a 1:1 anteroposterior to transverse diameter.”

Priorities of Care

None of the abnormal findings on their own are considered critical findings. However, if you notice asymmetrical lung expansion, be aware that this is associated with decreased ventilation. You should investigate whether there is decreased or absent air entry in the affected lung, which may be lagging behind or not expanding at all. Examples of underlying pathologies can include pneumothorax, atelectasis, pleural effusion, or partial or complete obstruction of the airway on the ipsilateral side.