13.5 Subjective Assessment

Subjective assessment of the neurological system involves asking questions about the health of the client and symptoms that might be caused by pathologies affecting the central and peripheral nervous system. A full exploration of these pathologies is beyond the scope of this chapter, but common problems associated with the neurological system include cerebrovascular accidents (stroke), cerebral aneurysms, traumatic brain injury, neurodegenerative disorders (dementias, Parkinson’s disease), movement disorders, seizures, diabetes-related neuropathy, spinal cord injuries, brain tumors, delirium, migraines, and neurodiverse conditions.

Common symptoms that may be related to the neurological system include headache, paresis, paralysis, paresthesia, dysphagia, dysarthria, visual changes/impairment, dizziness, balance issues, incoordination, seizures, tremors, confusion, fatigue, and nausea and vomiting. See Table 13.1 for guidance on subjective health assessment: many of the questions in the table align with the PQRSTU mnemonic (or variations of it). Try to ask questions in order of importance—you will not necessarily follow the sequential order of PQRSTU.

Always ask about any medications (prescribed or over the counter) or supplements the client is taking: name, dose, frequency, reason it was prescribed, and how long they have been taking it.

To help determine the validity of your findings, ask about other factors that may affect the neurological assessment such as alcohol or substance use. Try to evaluate the condition of the client in relation to their ability to comprehend questions and provide subjective data. On initial contact you will assess neurological status based on client responses: Are they awake? Are they paying attention to you?

Remember to ask questions related to health promotion. Depending on the context of the assessment, you may ask these questions and engage in a discussion during a subjective assessment or after an objective assessment. A section on “Health Promotion Considerations and Interventions” is included later in this chapter after the discussion of objective assessment.

Knowledge Bites

One common neurological condition is stroke, which is caused by a blocked or leaking cerebral artery (hemorrhage) causing damage in the brain. Its pathology is related to atherosclerosis and blood clots. If it is a temporary disruption of blood flow, it can result in a transient ischemic attack (TIA), commonly known as a mini-stroke. See Figure 13.9, which presents one type of stroke.

Another common condition is traumatic brain injury (TBI). Always monitor clients closely when they have experienced an injury to the head and brain, which might be caused by a fall or a physical bump or jolt to the body/head. Concussion is one possible serious consequence of this kind of injury, and it can disrupt normal brain function and lead to an altered level of consciousness. Symptoms of concussion include confusion, headaches, problems with memory and judgment, sensitivity to light, disruptions in sleep, and nausea and vomiting. Another serious risk associated with traumatic brain injury is increased intracranial pressure (pressure inside the skull), which can be related to swelling and bleeding in the brain. Symptoms of increased intracranial pressure include headaches, vision impairment, vomiting, and weakness.

| Symptoms | Questions | Clinical tips |

| Headache is a specific type of pain that can be felt in one certain location or all over the head. It can be described in many ways, including sharp, achy, throbbing, full, or squeezing with a viselike quality (a tight, strong, constricting feeling).

Headaches occur when nociceptors react to certain triggers. There are many causes. Although some headaches are related to musculoskeletal injuries, most are neurologically-related and can be related to inflamed or damaged nerves and triggers such as stress, alcohol, lack of sleep, and certain food and medications. Other influences can include muscular tension, dental or jaw problems, infections, and eye problems. |

Do you currently have a headache? Have you recently experienced any headaches that you are concerned about? Do you have frequent, severe, and/or recurring headaches that disrupt your day-to-day functioning? Additional probes if the client’s responses are affirmative may include: Quality/quantity: What does your headache feel like? How bad is your headache? Severity: Can you rate your headache on a scale of 0 to 10 with 0 being no pain and 10 being the most pain you have ever had? Region/radiation: Where do you feel your headache? Does it radiate anywhere? Provocative/palliative: Is there anything that makes your headache worse? Is there anything that makes your headache better? Timing/treatment: When did the headache begin? Was it sudden or gradual? What were you doing when it began? Is it constant or intermittent? How often do you get headaches? Have you taken anything to treat your headache? Have you taken any medications? Understanding: Do you know what is causing the headache? Do other members in your family experience similar headaches? Other: How does it affect your daily life? |

A severe headache with a quick onset is a cue for concern. This kind of headache can be related to conditions such as stroke. Patients may describe these types of severe headaches as the worst headache they have ever had or say they have never experienced pain like this before. Chronic headaches can be debilitating for people and affect day-to-day life. Migraines are a neurological condition. They are often described as throbbing, pulsating, and pounding intense headaches with associated symptoms such as nausea and vomiting, sensitivity to light, noise and smell, and auras. The causes of migraines are not yet clear, but they appear to be linked with genetic, environmental, and hormonal factors. |

| Paresis, paralysis, and paresthesia are common symptoms associated with neurological conditions such as stroke or nerve damage.

Paresis is decreased muscle strength of the voluntary muscle groups (often referred to as muscle weakness) whereas paralysis is the inability to move a muscle such as a limb. Paresthesia is abnormal sensory sensations such as numbness (loss of feeling), tingling (sometimes described as pins and needles), or other characteristics such as burning and prickling. |

Have you experienced any decrease in muscle strength? (Or inability to move a muscle/limb or abnormal sensations such as numbness or tingling in your face, arm, or leg?)

Remember to incorporate the language that the client uses into your probing questions (below, “XX” is used to represent the client’s language). Additional probes if the client’s responses are affirmative may include: Timing: Are you currently experiencing XX now? When did it begin? Did it come on suddenly or gradually? Is it constant or intermittent? What were you doing when it began? How often do you get it? Quality/quantity: What does it feel like? How bad is it? |

Falls are a safety concern with paresis, paralysis, and paresthesia. Fall risk assessment and prevention strategies are essential for client safety. If the client is mobile, strategies may include non-skid shoes or socks, use of prescribed mobility and assistive devices, and removal of hazards in the room. Nurses should consult with occupational therapists, physical therapists, and physiotherapists to decrease the client’s risk of falls.

Skin ulcers are another risk factor. Areas of the body that have lost or limited sensation or strength/movement should be assessed daily to decrease further damage to the area. Therefore, it may be important to assess clients using the Braden Scale for risk of pressure sores (see: Skin inspection via Braden Scale). Paresis, paralysis, and paresthesia decrease client mobility and therefore increase the risk of blood clots, urinary stasis, decreased peristalsis, and pneumonia. Passive range of motion (ROM) exercises should be performed to encourage continuous movement of the joints and muscles. Bell’s palsy is a facial nerve (CN VII) disorder causing temporary paralysis of the face in which it droops downwards (e.g., eye, cheek, mouth). However, similar symptoms can occur with Botox and other facial fillers/injections. A thorough assessment can help determine the origin of the cause. |

| Dysphagia and dysarthria are common symptoms associated with various neurological conditions such as stroke, brain tumor, and neurodegenerative diseases (e.g., Alzheimer’s, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s).

Dysphagia is impairment in swallowing. Clients often refer to it as difficulty or trouble swallowing and it is sometimes associated with pain. Dysarthria is a neuromotor impairment in speaking: clients may have difficulty saying or forming a word and may have reduced strength and speed when speaking. This can result in slow or slurred speech. |

Have you experienced any difficulty swallowing? Have you experienced any difficulty speaking?

Remember to incorporate the language that the client uses into your probing questions (remember that below, “XX” refers to the client’s language). Additional probes if the client’s responses are affirmative may include: |

New onset of dysphagia requires immediate action because it can be associated with conditions such as stroke and can lead to clinical deterioration as well as other complications such as choking or aspiration pneumonia. Always notify the physician or nurse practitioner. Additionally, if the client is experiencing new onset dysphagia, it is important to restrict food or fluids until this has been fully assessed. If possible, have the client sit upright (e.g., high Fowler’s position) or raise the head of the bed.

After any acute symptoms have been managed, consult with a speech language pathologist and dietician to discuss safety measures required during meal assistance to decrease risk of choking and aspiration pneumonia. Dysphagia management tips may include a special dysphagia diet, having the client sit upright, placing food on the noneffective side of the mouth, use of thickening fluids, and taking small bites. Dysarthria can cause slowed, slurred speech, which may be misdiagnosed as intoxication. A thorough assessment is required to determine the cause of dysarthria to ensure proper interventions are performed. Evaluating a client’s speech, including changes in speech, is part of the primary survey (ABCCS) assessment. Consult with a speech-language therapist on exercises to strengthen speech-related muscles and use of other communication aids. |

| Visual impairment is a disturbance in the client’s ability to see. Symptoms may include blurred vision, double vision, or partial or complete vision loss (central or peripheral) in one eye or both, a dark area in the visual field, shadowed vision, and/or light sensitivity. | Have you experienced any difficulty seeing or new changes to your sight? (You may choose to provide some examples.)

Remember to incorporate the language that the client uses into your probing questions (remember that below, “XX” refers to the client’s language). Additional probes if the client’s responses are affirmative may include: Timing: Are you currently experiencing XX now? When did it begin? Did it come on sudden or gradual? Is it constant or intermittent? How often do you get it? Quality/quantity: What does it feel like? How bad is it? Severity: Can you rate it on a scale of 0 to 10 with 0 being no XX and 10 being the most XX you have ever had? Region/radiation: Where in your eye do you experience it? Provocative/palliative: Is there anything that makes it worse? Is there anything that makes it better? Treatment: Have you taken anything to treat it? Have you taken any medications? Understanding: Do you know what is causing it? Other: How does it affect your daily life? |

A sudden change in vision is a priority in care. This cue is considered an emergency and needs immediate action. Sudden vision change could indicate a stroke and blood clot in the retinal artery. Immediate care is required to decrease the risk of permanent vision loss (blindness). |

| Dizziness, balance issues, and incoordination are neurological symptoms that are sometimes, but not always, associated with each other.

Dizziness refers to impaired spatial orientation in which clients describe feeling lightheaded, woozy, or that they might faint. It may be associated with nausea and syncope. (Vertigo is often described as dizziness, but vertigo is actually a different neurological symptom in which the client feels like they are spinning or the environment around them is spinning.) Balance issues are associated with feeling unsteady: the client feels like they may lose their balance or fall down. It can sometimes be associated with dizziness. Incoordination refers to loss of muscle control and lack of coordination such as the impaired ability to use parts of the body together (e.g., hands, arms, legs). It may result in impaired ability to walk smoothly or to use arms/hands together. |

Have you experienced any dizziness or a feeling of light-headedness?

Remember to incorporate the language that the client uses into your probing questions (remember that below, “XX” refers to the client’s language). Additional probes if the client’s responses are affirmative may include: Quality/quantity: What does XX feel like? Have you ever passed out or lost consciousness? How bad is it? Timing: Are you currently experiencing it now? When did it begin? Is it constant or intermittent? What were you doing when it began? Is it associated with position changes such as standing up? How often do you get it? Severity: Can you rate it on a scale of 0 to 10 with 0 being no XX and 10 being the most XX you have ever had? Provocative/palliative: Is there anything that makes it worse? Is there anything that makes it better? Treatment: Have you taken anything to treat it? Have you taken any medications? Understanding: Do you know what is causing it? Other: How does it affect your daily life? |

Fall risk assessment is essential to help the client take precautions against falling. Various fall assessment tools are available to help you systematically assess risk factors related to falls. These factors may include a history of falls/near falls; acute condition; ability to move around; mobility aids; or hearing, vision, or cognitive impairment. If the client has already been assessed, you should follow all recommendations, as well as all institutional policies to prevent falls. |

| Seizures are sudden changes in the brain’s electrical function that affect consciousness, muscle tone, movement, and sensations. For example, a client may be unable to move or walk, or may blink repeatedly, stare with no movement of eyes, experience stiffening and spasms of the muscles, loss of muscle tone, or exhibit sudden repetitive movements often described as twitching or jerking.

Tonic-clonic seizures refer to seizures in which a client’s muscles stiffen and twitch. In contrast, a client experiencing an absence seizure often stares off into space and/or repeatedly blinks. After the active (ictal) phase, many clients experience a recovery (postictal) phase that typically lasts minutes to 30 minutes (but for some this period may last for days), with symptoms including sore muscles, fatigue, confusion, and headache. The cause of a seizure may be unknown, or a result of a head injury, infection, high fever, certain medications, electrolyte imbalance, or other diagnosis/illness. A client who has two or more seizures is often diagnosed with epilepsy. |

Have you experienced a seizure?

Remember to incorporate the language that the client uses into your probing questions. Additional probes if the client’s responses are affirmative may include: Quality/quantity: What does it feel like or look like? Have you ever lost consciousness? How bad is it? Timing: When did you experience one last? How often do you experience them? At what age did you experience your first one? Provocative/palliative: Is there anything that makes it worse? Is there anything that makes it better? Treatment: Have you ever sought treatment for it? Have you taken anything to treat it? Have you taken any medications? Understanding: Do you know what is causing it? Other: How does it affect your daily life? Has anyone ever told you that you have short episodes where you stare off into space or repeatedly blink? |

Seizures can last a few seconds to many minutes or longer. In some institutions, seizures are treated when they last longer than 3 minutes or the client has 3 within 30 minutes.

Seizures can place the client in danger and safety precautions need to be considered. The client could be at risk of falling, accidents in the workplace (e.g., machinery), and pregnancy complications due to medications. Encourage clients to wear a medical alert bracelet. Consider the client’s own unique plan to manage their seizures. |

| Other neurological symptoms can include fatigue, tremors, fasciculations, confusion, hearing impairment, difficulty breathing, and nausea and vomiting.

For example, tremors can be related to neurological diseases (e.g., Parkinson’s disease) or other factors such as caffeine, certain medications, or overactive thyroid. |

Always ask one question at a time. Questions might include:

Have you experienced tremors or twitching-like movements? (Or confusion, fatigue, hearing impairment, difficulty breathing, or nausea and vomiting?) Use variations of the PQRSTU mnemonic to assess these symptoms further if the client’s response is affirmative. |

These symptoms can be related to the neurological system as well as other body systems. It is important to explore these symptoms specifically if the client answers affirmatively. |

| Personal and family history of neurological conditions and diseases.

As noted earlier, common issues associated with the neurological system include stroke, migraines, seizures, dementia, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, or other movement disorders. |

Do you have any chronic neurological conditions or diseases? Do you have a familial history of neurological conditions or diseases? (Give examples.)

If the client’s response is affirmative, begin with an open-ended probe: Tell me about the condition/disease. Remember to incorporate the language that the client uses into your probing questions. If the client has a personal history, probing questions might include: Timing: When were you diagnosed? Quality/quantity: How does it affect you? What symptoms do you have? Treatment: How is it treated? Do you take medication? Provocative/palliative: Is there anything that makes it worse? Is there anything that makes it better? |

Risk factors may be influenced by genetics and/or culture, so you should ask about the biological and non-biological nature of family.

Some neurological-associated diseases (e.g., Parkinson’s) are related to genetics, but it is more likely that environmental and cultural factors (such as family traditions and practices) play a larger role. Examples might include diet, sedentary lifestyle, and smoking. |

Priorities of Care

Respiratory distress is a first-level priority of care. Signs of respiratory distress and respiratory failure can be related to various neuromuscular disorders (Racca et al., 2019). Always screen for and recognize signs of respiratory distress (e.g., shortness of breath, stridor, desaturation, intercostal tugging, nasal flaring, difficulty talking). If any of these signs are present, notify the physician or nurse practitioner while supporting the client’s airway.

- If an airway is not patent, try to open the airway with a head-tilt-chin-lift and inspect the mouth and nose for obstructions.

- If oxygen saturations are low, try to wake the client if they are sleeping, sit them upright, and ask them to take a few deep breaths. Supplemental oxygen can be applied if there are standing orders on your unit.

- You may need to keep the client in a supine position if you suspect that they are deteriorating quickly and may go into respiratory or cardiac arrest. Notify the critical care response team (CCRT) or call a code in this case. Bag-mask-ventilation may be needed if the client is in respiratory arrest.

- If you suspect the client is choking, stay with the client and call for help while you place them in a high Fowler’s position. If they are able to, encourage them to cough and clear their airway. You may need to suction the oral cavity and airway, if possible. If you suspect a complete obstruction, use a combination of “back blows, abdominal thrusts, and chest thrusts” (Canadian Red Cross – What to do if an adult is choking).

Stroke is one of the most acute neurological pathological conditions. Acute stroke is a medical emergency. You should respond immediately by activating a Rapid Response, reporting your findings to a physician or nurse practitioner, or calling 911 in the community.

FAST—and more recently, BE-FAST—are common mnemonics used when assessing stroke (Aroor et al., 2017; Heart & Stroke of Canada, n.d.).

Balance: Are they having difficulty with balance, walking, coordination, or lower extremity weakness?

Eyes: Are they having difficulty with vision? (e.g., sudden trouble seeing out of one or both eyes or double vision).

Face: Is their face drooping, does it look asymmetrical, or do they have numbness on one side?

Arms: Do they have difficulty raising both arms or have numbness or weakness on one side?

Speech: Are they having trouble speaking, have slurred speech, or seem confused?

Time: Time is of utmost importance, so assess when the symptoms/signs began.

If you suspect a stroke, complete a brief scan (detailed later) and notify the physician or nurse practitioner. Depending on the hospital, you may notify the Critical Care Response Team or the Stroke Response Team. Assess and monitor vital signs, specifically blood pressure. Monitor for neurological deficits (e.g., decreased consciousness, confusion, dysphagia, dysphasia, ataxia, respiratory dysfunction such as Cheyne–Stokes respiration pattern). If you suspect a stroke, stay with the client and ensure their safety: restrict food/fluid intake and keep bed railings raised. (Hogge, C., Goldstein, L. B., & Aroor, S. R., 2024).

Contextualizing Inclusivity

The symptoms of neurological conditions (e.g., confusion, ataxia) and diseases or conditions that affect the neurological system can sometimes resemble intoxication from alcohol or substance use. It is important to reflect on your own biases and consider how they influence your perception of neurological symptoms and (in)actions to promote an inclusive approach.

Taking part in cultural safety and diversity, equity and inclusion training is one effective way to develop competence in working with diverse communities.

It is also vital to listen, validate, and act on what clients say. This is particularly important with racialized people because of the racism they have experienced and the serious effects it has on their lives and the health care they receive.

Knowledge Bites

Migraines and neuropathic pain management historically have been treated with opiods, however, other analgesics have demonstrated better results in treating neuropathic pain (Moulin et al., 2014), and opioids are also associated with increased risk of harm (Canadian Neurological Society, 2022).

References

Aroor, S., Singh, R., & Goldstein, L. (2017). BE-FAST (Balance, eyes, face, arm, speech, time). Reducing the proportion of strokes missed using the FAST mnemonic. Stroke, 48(2), 479-481.

Canadian Epilepsy Alliance (n.d.). Seizure First Aid. https://www.canadianepilepsyalliance.org/about-epilepsy/epilepsy-safety/seizure-first-aid/

Canadian Neurological Society (2022). Neurology: Five tests and treatments to questions. https://choosingwiselycanada.org/recommendation/neurology/

Canadian Patient Safety Institute (2015). Reducing falls and injuries from falls. https://www.patientsafetyinstitute.ca/en/toolsResources/Pages/Falls-resources-Getting-Started-Kit.aspx

Epilepsy Canada (n.d.), https://www.epilepsy.ca/seizures

Heart & Stroke of Canada (2022). Canadian Stroke Best Practice Recommendations: Acute Stroke Management, 7th edition. https://www.strokebestpractices.ca/-/media/1-stroke-best-practices/acute-stroke-management/csbpr7-acute-stroke-management-module-final-eng-2022.pdf?rev=44cca46747ed4f4c8870b8a135184f5a

Heart & Stroke of Canada (n.d.). Signs of stroke. https://www.heartandstroke.ca/stroke/signs-of-stroke

Hogge, C., Goldstein, L. B., & Aroor, S. R. (2024). Mnemonic utilization in stroke education: FAST and BEFAST adoption by certified comprehensive stroke centers. Frontiers in neurology, 15, 1359131. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2024.1359131

Olanlesi-Aliu, A., Alaazi, D., & Salami, B. (2023). Black health in Canada: Protocol for a scoping review. JMIR Research Protocols, 12, e42212.

Racca, F., Vianello, A., Mongini, T., Ruggeri, P., Versace, A., Vita, G. L, & Via G. (2019). Practical approach to respiratory emergencies in neurological diseases. Neurological Sciences, 41, 497-508.

Rexrode, K., Madsen, T., Yu, A., Carcel, C., Lichtman, J., & Miller, E. (2022). The impact of sex and gender on stroke. Circulation Research, 130(4), 512-528. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.319915

Vervoort, D., Kimmaliardjuk, D., Ross, H., Frames, S., Ouzounian, M., & Mashford-Pringle, A. (2022). Access to cardiovascular care for Indigenous Peoples in Canada: A rapid review. Canadian Journal of Cardiology Open, 4(9), 782-791.

Palpation of the abdomen provides information about the organs associated with the GI system. The palpation technique follows auscultation, so the abdomen is already exposed. Additionally, you should not palpate the abdomen if vascular bruits are present (e.g., aortic, renal, iliac, and femoral). If the client has experienced a physical injury or trauma to the abdomen, you also might not palpate the abdomen.

Remember, always palpate on bare skin.

Palpation of the abdomen involves the following steps (see Video 3):

1. If not already, ask the client to bend their knees up and ensure they are draped.

2. Use the pads of your four fingers to gently palpate the abdomen, keeping your fingers together and your wrist and forearm at about the same plane as the client’s body.

- Avoid a more angled position: this will create a feeling that you are poking the client in the abdominal region, which can be uncomfortable and also does not permit you to assess the area as well.

- Only the pads of your fingers should be touching the client during light palpation.

3. Begin in the right lower quadrant and proceed clockwise. If the client indicates they have pain in the right lower quadrant, begin in the right upper quadrant instead and palpate the area with pain last.

4. Press down about one to two centimeters (light palpation) and move your fingers together in a circular motion.

- Sometimes, you will notice voluntary guarding (tense abdominal muscles) as a result of nervousness, pain, cold room temperature or hands of the nurse, or ticklishness. The tenseness of the muscles usually covers the whole abdomen (i.e., bilateral). It can help to ask the client to take a deep breath when you palpate to help them relax the muscles. Remember to use light palpation and do the painful area last. Only expose the abdomen as long as needed so the client stays warm, and warm your hands by rubbing them together. If the client is ticklish, use a sandwich technique: put their hand on top of your palpating hand, and place your other hand over top of both to control the pressure.

5. Lift fingers up together and move on to the next location, ensuring that you palpate every square centimeter of the abdomen in all four quadrants.

6. Assess the following:

- Overall consistency (soft or firm) and associated pain/tenderness. The abdomen is usually soft upon palpation. Note the location of any firmness and any associated pain/tenderness. The consistency of the abdomen is influenced by the amount of adipose tissue or muscle, but these are symmetrical across the abdomen.

- Presence of masses. Describe any masses in terms of location, size (dimensions), shape, consistency (soft or firm), and associated pain/tenderness.

- Presence of swelling. Note the location of any swelling.

- Presence of pain. If the client feels pain/tenderness upon palpation, note the location and ask them to rate the severity on a scale of 0 to 10.

- Presence of rigidity and spasms. Rigidity is involuntary firmness/hardness of the abdominal muscles associated with peritoneal inflammation. This rigidity is felt over the inflamed area; it is not bilaterally symmetrical and not voluntary like guarding. You may also feel spasms which are muscle contractions that are often painful.

7. Note the findings.

- Normal findings might be documented as: “Abdomen soft to touch with no masses, swelling, pain, and rigidity.”

- Abnormal findings might be documented as: “Client noted generalized pain all over abdomen upon palpation, rating it 5/10. Abdomen firm to touch in all quadrants. Left lower quadrant mass, circular in shape, 5 x 5 cm.”

Video 3: Palpation of the abdomen.

Clinical Tip

Priorities of Care

Urgent surgical intervention is required when a client has appendicitis (inflammation of the appendix that is at risk of perforating). In these cases, the client usually presents with an increasing level of pain in the right lower quadrant, often beginning in the periumbilical region. This can also be associated with lack of appetite, nausea, vomiting, fever, chills, and muscle rigidity. If you suspect appendicitis, notify the physician immediately. Continue to monitor the client, measure vital signs, do not allow the client to take anything by mouth, and begin an intravenous if there are standing orders. A physician or nurse practitioner may assess for rebound tenderness, which involves palpating in the right lower quadrant and quickly removing one’s hand. Positive rebound tenderness (pain when the assessor removes their hand) is often indicative of appendicitis.

All abnormal findings (e.g., masses, swelling, pain, rigidity) should be further investigated with a focused abdominal assessment. Report any new, worsening, or unexpected findings to the physician or nurse practitioner.

Activity: Check Your Understanding

The guiding approaches of health assessment refer to specific conventions of when and what type of health assessment to perform. For example, how often should you perform an assessment on the client? What type of assessment should you perform and how comprehensive should it be? Approaches always depend on the context of the situation. As you become more experienced, you will also be able to pick up on cues that require additional assessment.

Health Assessment Frequency

The frequency of a health assessment is determined by the setting (e.g., primary care, long term care, acute care) and the health and clinical status of the client.

- The frequency of a primary care visit depends on the client’s age and their health status and needs. For example, guidelines have been established for the frequency of well-baby and childhood visits and maternal health visits. Also, clients with complex healthcare needs (such as multiple morbidities) will need to see their primary care practitioner more often than a healthy adult.

- The frequency of assessment in a long-term care setting is often determined by concerns voiced by the client, care provider, assistant, tech or the nurse.

- The frequency of assessment in acute care (such as medical or surgical units) will be at least every four hours. In critical care, this frequency is increased to usually every 1–2 hours at least. Clients in critical care are usually on a monitor in which their heart rhythm and vital signs such as oxygen saturation and heart rate are constantly monitored and alarm bells will signal if there is an abnormal change. Although there may be a standard for the frequency of assessment based on the unique population you care for or the institution policy, you must be aware that escalation of care and increased frequency may be needed based on the nurse’s assessment and the client’s clinical status. For example, at times clients may require constant observation (e.g., post-surgery, in critical care environments, a client who is unstable or may show signs of deterioration, or a client in mental health distress with suicide ideation or post-attempt).

Health Assessment Types

There are several ways to describe health assessment types. In this chapter, we refer to four types including: primary survey; focused assessment; head-to-toe (abbreviated version); and complete health assessment. As per Table 1, the type of health assessment to be performed is determined based on the context of the situation.

Table 1 : Types of health assessment

|

Type of Assessment |

Recommendations |

|

Primary survey |

According to current recommendations, all assessments should begin with a primary survey because this structured assessment helps nurses recognize and act on signs of clinical deterioration (Considine & Currey, 2014) that are correlated with death (Douglas et al., 2016). A primary survey collects data in order of importance, and it is aligned with most institutions’ rapid response systems (Considine & Currey, 2014). This recommendation marks a change from the tradition of beginning an assessment with vital sign measurement (Considine & Currey, 2014) or doing a head-to-toe assessment. A primary survey will help you determine if urgent intervention is needed or whether you should perform a focused assessment or a head-to-toe assessment. This change in assessment practice is still relatively new. Thus, you may encounter healthcare professionals who are not familiar with this shift in practice and the primary survey. It can provide an opportunity for discussion and learning. |

|

Focused assessment |

This type of assessment is performed in all areas of care (e.g., primary care, emergency, long-term care, medical, surgical). Because of its specificity, it usually involves a focus on a limited number of body systems based on the health concern, similar to an episodic database. For example, a client’s reason for seeking care may be an “achy knee.” Thus, the nurse’s assessment will be focused on the musculoskeletal system. Another example may be chest pain. Because there are multiple causes of chest pain, you may need to do a cardiac, respiratory, and musculoskeletal assessment. Another example is a follow-up assessment: a client may have been prescribed a new medication for high blood pressure and needs a follow-up assessment a couple of weeks later to determine the effects. |

|

Head-to-toe assessment (abbreviated) |

Typically, a head-to-toe assessment should take about 10 minutes and should be performed at the beginning of your shift and when you first interact with a client. There are variations of this assessment based on the client situation, reason for seeking care, and institution/unit. A head-to-toe assessment usually includes attention to overall wellbeing/needs, pain, vital signs, specific assessments related to neurological, cardiovascular, peripheral vascular, skin, respiratory, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, activity/rest, and wounds/dressings, IV sites, drains/tubes, and oxygen. Based on the collected data, this type of assessment may influence the need for a more focused examination of a specific body system. For example, you may notice the client has a bloated and hard abdomen. Based on these cues, you should complete an abdominal assessment. A more complete assessment/head-to-toe may be needed in certain situations when a comprehensive assessment is warranted (see next section on complete health assessment). |

|

Complete health assessment |

A complete health assessment may take 30–60 minutes depending on the client and the complexity of their health issues. It may be performed for several reasons, often when clients have complex care needs. It is often performed upon admission to a long-term care home or rehabilitation, and sometimes in a primary care setting with new clients. It may also be performed in acute settings when a client has complex health problems and diagnoses have been problematic. This kind of assessment can vary based on the client situation, developmental stage, reason for seeking care, and institution/unit. |

Clinical Tip

When you are new to a work environment, you should inquire about the typical conventions surrounding assessment frequency and type. It is also always helpful to ask your clinical instructor/preceptor about their approach to assessment.

When conducting these assessments, it is important to assess the client's level of consciousness and level of orientation. New onset disorientation and/or a decrease in level of consciousness are important cues that could indicate clinical deterioration and thus, require immediate intervention. If not yet completed, a primary survey should be done and findings shared with the physician or nurse practitioner.

Level of consciousness is the client's state of awareness and response to stimuli (voice/sound or physical). Their level of consciousness is described as:

- Alert and oriented: This means that the client is awake (or easily arouses to your voice), engages appropriately in interactions with you, responds appropriately to your questions, and oriented to person, place, time, and self.

- Confused and disoriented: This means that the client shows altered cognition such as difficulty in memory retention, difficulty following commands, uncertain about the environment around them, inattention, and shows signs of disorientation in terms of person, place, time, and self. They may have delayed or inappropriate/incorrect responses to your questions.

- Lethargic: This means that the client is slow/sluggish to arouse to stimuli. For example, you need to say their name loudly or multiple times or physical shake their arm. They are sleepy, lack energy, slow to respond to your questions, but answers appropriately and are oriented.

- Obtunded: This means that the client has a significant impairment in their level of consciousness and requires a significant and continuous stimuli (loud voice, vigorous shaking of the arm). They have difficulty to respond because of the impairment, need constant coaxing to respond, can only answer very simple questions with one word responses that are difficult to hear and understand. Without stimuli, they will immediately return to sleep.

- Unconsciousness: This means that the client does not respond to any stimuli and has no purposeful motor responses.

Level of orientation is assessed by asking the client questions related to:

- Place (questions to ask: Do you know where you are? They may know they are in a hospital because of the room. Thus, you may probe with the question, do you know what hospital you are in?).

- Time (questions to ask: Do you know what date it is? Do you know what day of the week it is? Do you know what month it is? Do you know what year it is?).

- Person (question to ask: Do you know who I am? They may say "yes", but you should probe with the question, can you tell me who I am? They may be able to identify you as a nurse, but forget your name in some cases), - Self (question to ask: Do you know who you are? If they respond "yes", you should probe with the question, can you tell me your name?).

- Situation (questions to ask: What brought you in? Why are you here?).

A normal response is that the client is oriented to place, time, person and situation. If they are disoriented, you indicate what they are disoriented to. You may indicate oriented to place, person and situation, disoriented to time. It is important to consider context when assessing level of orientation. For example, a client may not be aware of the specific date, but knows the day of the week or month.

References

Considine, J., & Currey, J. (2014). Ensuring a proactive, evidence-based, patient safety approach to patient assessment. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 24, 300-307. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12641

Douglas, C., Booker, C., Fox, R., Windsor, C., Osborne, S., & Gardner, G. (2016). Nursing physical assessment for patient safety in general wards: Reaching consensus in core skills. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25, 1890-1900. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13201

Objective assessment involves the collection of data that you can observe and measure about the client’s state of health. Examples of objective assessment include observing a client’s gait, physically feeling a lump on client’s leg, listening to a client’s heart, tapping on the body to elicit sounds, as well as collecting or reviewing laboratory and diagnostic tests such as blood tests, urine tests, X-ray etc. Typically, an objective assessment is conducted following the collection of subjective data.

The purpose of the objective assessment is to identify normal and abnormal findings. The abnormal findings are cues that signal a potential concern. An important part of the nursing process to ensure client safety and effective care is:

- Recognizing abnormal cues.

- Acting on abnormal cues.

Failing to recognize or act upon abnormal cues can lead to significant negative consequences for the client.

Objective data are analyzed in combination with your subjective assessment to make a clinical judgement. A clinical judgement is the outcome of thinking critically about the data, analyzing the cues as a whole, making decisions about the most significant concerns to address, and identifying how to best address these concerns based on the existing evidence (National Council of State Boards of Nursing, 2018). As a healthcare professional, developing strong clinical judgement is essential to ensuring client safety and maintaining your competency. Your clinical judgement will guide the prioritization and sequencing of assessment techniques. Your assessment of cues (both subjective and objective) will help you determine what data warrant further investigation and assessment. Therefore, it is important to think critically about the findings you collect during an assessment: Are they normal or abnormal for this specific client? Do they require you to act and/or seek further assistance?

Clinical Tip

Recognizing and acting on assessment findings

As a nursing student, you must have timely discussions with your clinical instructor or preceptor to assess the significance of abnormal findings. You will need to take initiative, develop confidence in seeking assistance, and never ignore an abnormal finding.

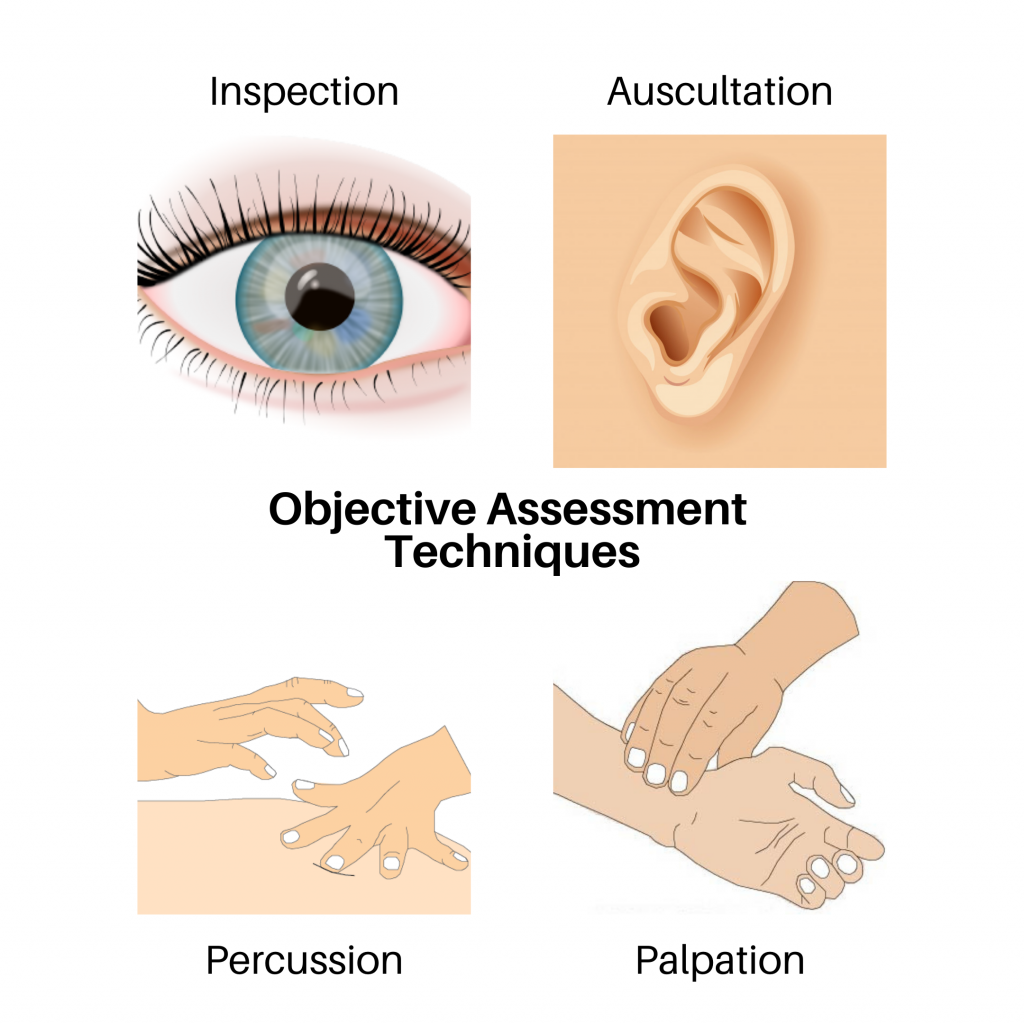

In this chapter, you will focus on four objective assessment techniques: inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation. These involve your senses of sight, hearing, and touch (see Figure 1.1). You should also be aware of your sense of smell when conducting any physical assessment, as certain odours can act as a cue; for example, a foul odour may indicate an infection.

- Inspection involves your visual sense to observe the client.

- Palpation involves your sense of touch to physically feel areas of the body.

- Percussion involves a combination of touch and hearing, but your focus is on hearing sounds when tapping the areas of the body.

- Auscultation involves your sense of hearing while listening to areas of the body with a stethoscope.

Figure 1.1: Objective assessment techniques

These techniques should be performed with methodical and deliberate action. Always perform inspection first because it is the least invasive and does not involve physical touch. Inspection also allows you to establish a baseline for your assessment. For example, if you observe someone crouched over in pain, this will inform the sequence of your subsequent assessment techniques. Typically, palpation, percussion, and then auscultation follow inspection. The sequencing of techniques may be rearranged for several reasons, including which system is being assessed and for safety reasons. For example, when assessing the abdomen, auscultation is generally performed before percussion and palpation. Client safety and comfort also influence the sequence of objective techniques. For example, with a sleeping infant, you should perform inspection and auscultation while the child is calm and to avoid awakening the client. You will learn more about modifications to the sequencing of techniques as you learn about specific body systems. Determining technique sequence also comes with experience.

When applicable, these IPPA techniques are used to assess body systems (e.g., eyes, ears, heart and neck vessels, lungs and thorax, abdomen, musculoskeletal). However, not all techniques are applicable to all systems. For example, you would not auscultate an eye because it does not emit a sound that would give you relevant data. Additionally, developmental stage and age can influence how some IPPA techniques are performed and also the determination of normal and abnormal findings. For example, normal heart rates vary significantly between a newborn compared to an adult.

Before you explore each technique, let’s discuss what you need to do before you begin the objective assessment!

Voices of Experience

Your foundational IPPA assessment techniques and the resultant findings will give you a baseline understanding of the client’s health status. These physical assessment skills, combined with subjective health assessment, are important parts of clinical judgement and can act as a prompt for urgent action, transfer to a higher level of care, and further diagnostic technologies. Your IPPA assessment skills will be even more important in areas with less access to resources and diagnostics (e.g., rural and remote areas and underdeveloped regions).