13.9 Introduction to Cranial Nerves

In total, 12 paired cranial nerves originate within the brain and brainstem and extend into multiple branches (see Figure 13.11).

The 12 cranial nerves are related to sensory and/or motor functions (see Table 13.4). Sensory refers to senses such as seeing, hearing, tasting, smelling, and touching, while motor refers to movement. Innervation and associated responsibilities of the nerves can be affected when the nerve is damaged from a physical trauma (e.g., an accident), a surgical intervention, a brain lesion (related to a stroke, cerebral inflammation, tumor, aneurysm), or a condition resulting in demyelination (e.g., multiple sclerosis).

The next section explores some of the most common approaches that nurses use to examine the 12 pairs of cranial nerves. Keep in mind that there are many ways to assess cranial nerves, and an abnormal finding may indicate damage to the nerve. These findings should be considered in the context of the complete neurological examination.

| Nerves | Neurological signs and symptoms (when CN is damaged) |

| CN I (1) Olfactory nerves

Sensory nerves related to smell. |

|

| CN II (2) Optic nerves

Sensory nerves related to visual acuity (how well a person’s eyes can identify shapes and details of an object at a specific distance) and visual fields (periphery of vision). This nerve is also responsible for sending a message to the brain when light is introduced to the eye when assessing pupillary light reflex to evaluate CN III. |

|

| CN III (3) Oculomotor nerves

Sensory nerves related to pupil innervation (pupillary constriction) and lens shape. Motor nerves related to upper eyelid movement and eye muscle movement specific to four muscles (superior rectus, inferior rectus, medial rectus, and inferior oblique) controlling eye movements: diagonal upward (both inward and outward), diagonal downward-outward, horizontal inward. |

|

| CN IV (4) Trochlear nerves

Motor nerves related to eye muscle movement specific to one set of muscles (superior oblique) controlling the diagonal downward-inward movement of the eye. |

|

| CN V (5) Trigeminal nerves

Sensory nerves related to the sense of touch on facial dermatomes (forehead, maxillary, mandible) and the cornea. Motor nerve related to the innervation of the temporal and masseter muscles of the face. |

|

| CN VI (6) Abducens nerves

Motor nerves related to eye muscle movement specific to one set of muscles (lateral rectus) controlling the horizontal outward movement of the eye. |

|

| CN VII (7) Facial nerves

Sensory nerves related to taste on the dorsal side of the tongue on the anterior two-thirds (at the front of the tongue). Motor nerves related to movement of the facial muscles (i.e., facial expressions). |

|

| CN VIII (8) Vestibulocochlear nerves

Sensory nerves related to balance (vestibular) and hearing (cochlear). This is a set of two nerves including the vestibular nerves and the cochlear nerves (with some motor function). |

|

| CN IX (9) Glossopharyngeal and CN X (10) Vagus nerves

These nerves work together: CN IX carries afferent messages to the brain and CN X carries efferent messages to the affected area. Sensory nerves (CN IX) related to taste on the dorsal side of the tongue on the posterior third (toward the back of the tongue). Motor nerves related to movement of the soft palate, uvula, and pharynx, and some muscles of the tonsillar pillars, swallowing, and speech. |

|

| CN XI (11) Spinal accessory nerves

Motor nerves that innervate and control the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles. |

|

| CN XII (12) Hypoglossal nerves

Motor nerves related to tongue movement and strength. |

|

Authors

Dr. Jennifer Lapum 1

Michelle Hughes 2

Dr. Erin Ziegler 1

Evan Accettola

Alexis Andrew

Sita Mistry

1 Toronto Metropolitan University

2 Centennial College

Funding

This project is made possible with funding by the Government of Ontario and through eCampusOntario’s support of the Virtual Learning Strategy. To learn more about the Virtual Learning Strategy visit: https://vls.ecampusontario.ca

Acknowledgments

Instructional design consultant: Nada Savicevic, MA Interactive Design, MArch, BSc (Eng), Instructional Designer, Office of e-Learning, Toronto Metropolitan University, Toronto, Canada

Biology consultant: Charlotte Youngson, PhD, Department of Chemistry and Biology, Toronto Metropolitan University, Toronto, Canada

Copyeditor, Linn Clark Research and Editing Services, Toronto Canada

Pressbooks consultant: Sally Wilson, Web Services Librarian, Toronto Metropolitan University, Toronto, Canada

Accessibility consultant: Adam Chaboryk, IT Accessbility Specialist, Toronto Metropolitan University, Toronto, Canada

Copyright consultant: Ann Ludbrook, Copyright and Scholarly Engagement, Librarian, Toronto Metropolitan University, Toronto, Canada

Thank you to Centennial College Health Studies Lab Team for supporting this project and sharing their lab space to film the assessment videos.

Artist / Illustrators

Arina Bogdan, BScN, RN (chapter 3-5 images, and cover art)

Pelageya Grebneva, Ryerson, Centennial, George Brown Collaborative Nursing Degree Program, Toronto, Ontario, Canada (chapter 3-5 images)

Levar Bailey (chapter 2 figure)

Student Advisory Committee

Christina Amirkhanian, Toronto Metropolitan, Centennial, George Brown Collaborative Nursing Degree Program, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Samin Barakati, Toronto Metropolitan, Centennial, George Brown Collaborative Nursing Degree Program, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Caitlyn Healey, Toronto Metropolitan, Centennial, George Brown Collaborative Nursing Degree Program, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Mehak Khawaja, Toronto Metropolitan, Centennial, George Brown Collaborative Nursing Degree Program, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Tommy Lin, Toronto Metropolitan, Centennial, George Brown Collaborative Nursing Degree Program, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Maruel Isaac Sanchez, Toronto Metropolitan, Centennial, George Brown Collaborative Nursing Degree Program, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Conner Sorley, Toronto Metropolitan, Centennial, George Brown Collaborative Nursing Degree Program, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Lauren Sweeney, Toronto Metropolitan, Centennial, George Brown Collaborative Nursing Degree Program, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Gabriel Umrao, Toronto Metropolitan, Centennial, George Brown Collaborative Nursing Degree Program, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Steven Zagada, Toronto Metropolitan, Centennial, George Brown Collaborative Nursing Degree Program, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

- Apply subjective assessment skills.

- Apply objective assessment skills.

- Use clinical judgment.

- Integrate health promotion interventions into actions.

The gastrointestinal system (also called the GI system) is important to assess because it is responsible for nutrition, digestion, absorption, hydration, and defecation. You may also have heard it referred to as the digestive system. As a nurse, your assessment of the GI system provides information about how the system is functioning and potential cues that require action.

GI System Components

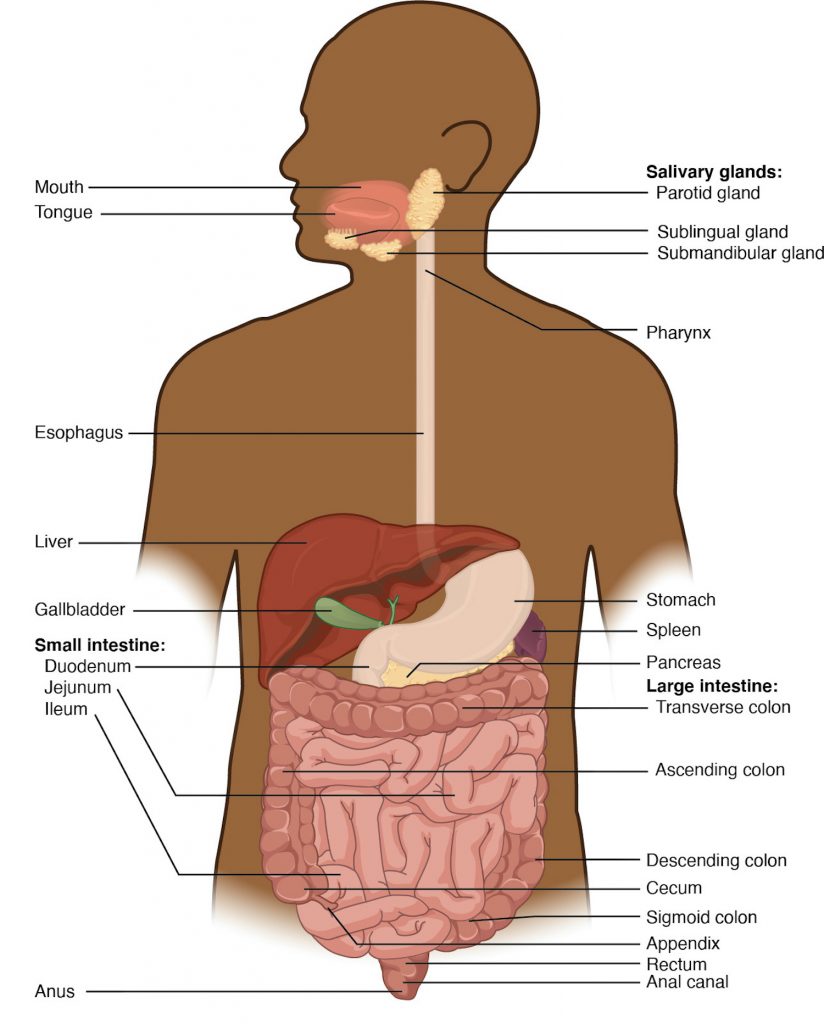

As per Figure 1, the main components of the GI system include:

- The upper GI tract (oral cavity, esophagus, stomach, and the first part of the small intestine [i.e., the duodenum]).

- The lower GI tract (small and large intestine, rectum, anus).

- The accessory glands and organs (salivary glands, liver, pancreas, gallbladder) and lymphatic organs and tissue (tonsils, spleen, appendix).

Figure 1: GI tract.

(Attribution statement for image at bottom of page)

You have already learned about the anatomy and physiology of the GI system; See Video 1 for a quick overview:

Video 1: Overview of the GI system. (Attribution taken from: https://www.khanacademy.org/science/high-school-biology/hs-human-body-systems/hs-the-digestive-and-excretory-systems/v/meet-the-gastrointestinal-tract)

Activity: Check Your Understanding

Attribution statement for Figure 5.1 - Image from: J. Gordon Betts, Kelly A. Young, James A. Wise, Eddie Johnson, Brandon Poe, Dean H. Kruse, Oksana Korol, Jody E. Johnson, Mark Womble, Peter DeSaix, Anatomy and Physiology, OpenStax, Apr 25, 2013, Houston, Texas. Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/23-1-overview-of-the-digestive-system. Licenced under Creative Commons CC BY 4.0.

Subjective assessment of the GI system involves asking questions about the health of the client and symptoms related to pathologies of the associated organs and glands. Although a full understanding of these pathologies is beyond the focus of this chapter, common issues associated with the GI system include dental cavities, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), cancer, ulcers, hepatitis, ascites, ileus, irritable bowel syndrome, constipation, hernias, and hemorrhoids.

Knowledge Bites

Ulcers have emerged over the last century as a common condition. For decades, researchers believed the cause was related to increased acid production, foods, and stress. In the early part of this century, researchers found that Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) bacteria are a common cause of gastric and duodenal ulcers (Ahmed, 2005; Kusters et al., 2006). Since then, there has been a major shift in both diagnostics and treatment, including testing for H. pylori and use of medications including antibiotics and proton pump inhibitors. Correct treatment is important considering that untreated ulcers can lead to perforation of the gastric or intestinal wall (depending on location) followed by peritonitis and possible hemorrhage.

Common symptoms that can be related to the GI system include pain, nausea and vomiting, appetite changes, bowel patterns changes including diarrhea and constipation, bloating, and flatulence. See Table 1 for guidance on a subjective health assessment related to common symptoms, questions, and clinical tips. Many of the questions in this table align with the PQRSTU mnemonic. You should consider asking questions in order of importance, thus you do not follow the sequential order of PQRSTU.

You should also ask about any medications (prescribed, over the counter, or illicit) the client is taking, including the name, dose, frequency, reason for taking, and how long they have been taking it. Many types of medications can cause GI upset (nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhea).

Always use questions focusing on health promotion during an assessment. Depending on the context, you might ask these during the subjective assessment or after an objective assessment. A “Health Promotion Considerations and Interventions” section is provided later in this chapter after the discussion of an objective assessment.

Table 1: Common symptoms, questions, and clinical tips

|

Symptoms |

Questions |

Clinical tips |

|---|---|---|

|

Dysphagia is difficulty related to swallowing and can involve difficulty related to swallowing saliva, food, and/or fluids. It can be caused by a variety of conditions that can be associated with structural issues (inflammation) or neural issues (stroke). |

Do you have any current or recent difficulty swallowing? If the client's response is affirmative, additional probes may include: Quality/quantity: Tell me about the difficulty. What does if feel like? How bad is it? Region: Where do you feel it (e.g., in the throat area or lower in the upper esophageal area)? Understanding: Do you know what is causing it? Do you have any related symptoms (e.g., pain, swollen glands, excessive saliva, drooling)? Timing: When did it begin? What were you doing when it began? Is it constant or intermittent? Provocative/palliative: Is there anything that makes it worse? Is it aggravated or associated with eating or drinking? Is there anything that makes it better (e.g., position)? Treatment: Have you treated it with anything? Do you take any medications for it? |

New onset of dysphagia requires immediate action because it can lead to clinical deterioration and complications such as choking or aspiration pneumonia. If a client is experiencing new onset dysphagia, it is important to restrict food or fluids until it has been fully assessed. If possible, have the client sit upright (e.g., high fowler position) or raise the head of the bed. |

|

Oral lesions, discolourations, and bleeding gums. |

Do you currently have or have you had any chronic issues with sores/ulcers in your mouth, discolouration of your mouth, or bleeding gums? If the client response is affirmative, additional probes may include: Region: Where is it located? Quality/quantity: Tell me about it. How bad is it? Timing: When did it begin? What were you doing when it began? Is it constant or intermittent? Provocative/palliative: Is there anything that makes it worse? Is there anything that makes it better? Treatment: Have you treated it with anything? Do you take any medications for it? Understand: Do you know what is causing it or what it is related to? |

The first action is to inspect the mouth so that you can provide an objective assessment. Interventions will depend on the cause. For example, bleeding gums may be caused by brushing too hard or increased vascularity associated with pregnancy; they can also be caused by gum disease, so you may need to refer the client to a dentist. |

|

Xerostomia is dry mouth; it can be mild and easily treated or severe and affecting a client’s quality of life, health, and overall wellbeing. It can be associated with dehydration, certain medications, cancer treatments such as radiation therapy, and alcohol and drug use. |

Do you currently have a dry mouth or have you had any chronic issues with dryness in the mouth? If the client’s response is affirmative, additional probes may include: Quality/quantity: Tell me about your dry mouth. What does it feel like? How bad is it? Timing: When did it begin? Is it constant or intermittent? Understanding: Do you know what is causing it or what it is related to? Provocative/palliative: Is there anything that makes it worse? Is there anything that makes it better? Other questions may include: How much fluids do you drink per day? Are you taking any medications or radiation therapy? How much alcohol do you drink per day? Do you take any drugs? Do you smoke? Treatment: Have you treated it with anything? Do you take any medications for it? Tell me about how much fluids you drink per day |

Interventions will depend on the cause. Older adults are at risk for xerostomia due to decreased intake of fluids as well as increased usage of medications and certain medical conditions that affect the functioning of the salivary glands. It may be as simple as encouraging the client to drink more water, limit sodium, limit alcohol and drug use, and use sugar-free gum or lozenges. You should also ask about smoking, which can further aggravate symptoms related to dry mouth. If a client has chronic dry mouth, inspect their mouth for associated symptoms such as cracked lips, gum disease, tooth decay, and oral lesions. You should also assess whether it is affecting the client’s nutrition or other elements of daily life such as wearing dentures, especially when the client is an older adult. |

|

Mouth pain or sensitivities can involve a sore throat, tooth pain or sensitivities, and jaw pain. |

Do you currently have or have you had any issues with mouth pain or sensitivities such as a sore throat, tooth pain or sensitivities, or jaw pain? If the client response is affirmative, additional probes may include: Region: Where is it located? Quality/quantity: Tell me about it. How bad is it? Timing: When did it begin? What were you doing when it began? Is it constant or intermittent? Provocative/palliative: Is there anything that makes it worse? Is there anything that makes it better? Treatment: Have you treated it with anything? Do you take any medications for it? Understand: Do you know what is causing it or what it is related to? |

These symptoms require an objective assessment to assess further GI signs, or signs related to other systems. First, assess whether the jaw pain might be cardiac-related. Angina is a critical finding that requires immediate intervention and can radiate to the jaw area. In order to determine this, you should assess what brought the pain on. For example, was there a physical injury? If not, are there other related factors and symptoms. Another common cause of jaw pain is bruxism, which can be caused by stress. These types of symptoms and tooth pain and sensitivities usually require referral to a dentist. |

|

Upper and lower GI pain can be associated with many conditions. This is an unpleasant sensation that is described subjectively in a ways such as tenderness, achy, discomfort, burning, or sharp pain. |

Do you have any current or recent pain in the esophageal or abdominal region (or unpleasant sensations such as tenderness)? If the client’s response is affirmative, additional probes may include: Region: Where do you feel the pain/sensation? Does it radiate anywhere? Quality/quantity: Tell me about it. What does it feel like? How bad is it? Timing: When did it begin? What were you doing when it began? Is it constant or intermittent? Severity: Can you rate it on a scale of 0 to 10 with 0 being no pain and 10 being the worst pain you have had? Provocative/palliative: Is there anything that makes it worse? Is there anything that makes it better? Treatment: Have you treated it with anything? Do you take any medications for it? Understand: Do you know what is causing it or what it is related to? |

With children, always tailor questions to their developmental stage. With infants and pre-verbal or non-verbal children, you may need to focus on objective assessment such as behavioural and physiological signs of pain. Remember that GI pain is sometimes cardiac-related (angina). You must rule out this possibility because it can be a critical finding that requires urgent intervention. |

|

Nausea and vomiting (emesis) are common symptoms associated with many conditions. Nausea is an uneasiness/queasy feeling in the stomach associated with the urge to vomit. Vomiting (emesis) is the emptying of the GI tract (usually the contents of the stomach/esophagus) through the mouth. When associated with pregnancy, this is called hyperemesis gravidarum (morning sickness). |

Do you have any current or recent nausea and vomiting? If the client’s response is affirmative, additional probes may include: Timing: When did it begin? When was the last time? What were you doing when it began? Is it constant or intermittent? Is it associated with eating? Quality/quantity: Tell me about it. What does the nausea feel like? How bad is it? If the client indicates vomiting, ask: How much do you vomit? Is it undigested food? What colour is it? Is there blood in it? Provocative/palliative: Is there anything that makes it worse? Is there anything that makes it better? Treatment: Have you treated it with anything? Do you take any medications for it? (If so, do they help?) Understand: Do you know what is causing it or what it is related to? Do you have any other related symptoms (e.g., stomach pain, fever)? |

Nausea and vomiting are usually not serious, and are often associated with a bacterial or viral infection. However, they may be associated with a more serious condition such as appendicitis, a concussion, or an intestinal blockage. Hematemesis is a serious concern that suggests GI bleeding. It is important to assess the colour, as this can help determine where the bleeding is coming from and whether it is active bleeding or old, dried blood. For example, bright red suggests active bleeding from the upper GI system. You might also visualize vomit that has dark brown or black specks in it resembling coffee grounds, which is suggestive of bleeding. It is important to determine the cause and severity of the nausea and vomiting. Antiemetics are a class of drugs used to prevent and treat nausea and vomiting. Many types are available, including dimenhydrinate (Gravol). Assess the client for risk of dehydration, particularly among children or older adults or when vomiting is frequent with large quantities. Common signs of dehydration include dry mouth, cracked lips, decreased skin turgor, tachycardia, increased thirst, decreased urine output, delirium, and in infants, sunken fontanelles. |

|

Changes in bowel patterns can include constipation or diarrhea. These changes can be short-term or chronic and can be associated with many health conditions and other factors such as diet. Constipation refers to decreased frequency in bowel movements (BMs) (less than three per week) and difficulty having a BM (having to strain to push stool out, hard stool). Diarrhea refers to soft, loose, watery stools that are not formed and are frequent (three or more a day). |

Tell me about your normal bowel patterns? Probing questions may include: How often do you have a bowel movement? What is the consistency (soft or hard)? What colour is it? Have you ever noticed mucus or blood in it? Do you have any concerns about your bowel patterns? Do you take any medications to help you have a bowel movement (such as a stool softener or laxative)? Have you had any recent or frequent diarrhea or constipation? If the client has concerns about their bowel patterns or has reported a problem such as diarrhea or constipation, probe further with questions such as: Timing: When did it begin? When was the last time? Is it constant or intermittent? Is it associated with eating? Provocative/palliative: Is there anything that makes it worse? Is there anything that makes it better? Treatment: Have you treated it with anything? Do you take any medications for it (if so, do they help)? Understand: Do you know what is causing it or what it is related to? Do you have any other related symptoms (e.g., stomach pain)? |

Remember that normal bowel patterns vary from client to client. Some people, particularly older children/adolescents and young adults, may feel embarrassed to talk about bowel patterns. Try to normalize the discussion using statements like “I like to speak with all clients about their bowel patterns because it can provide information about your health.” An inclusive approach to assessment involves age- and culturally-appropriate terms. For example, not everyone will know what a BM is, so you may need to use words like “poop” or “number two.” Blood in the stool can appear as bright red or black/dark brown. Assessing the colour helps determine the cause, which can be something mild to something as severe as colorectal cancer. A focused assessment is important. If a client has constipation or diarrhea, choose an appropriate action based on the severity. Dietary changes and hydration are often helpful, but in some cases, severe constipation could be related to a bowel obstruction and requires urgent intervention. This may be associated with other symptoms such as abdominal pain and a distended abdomen. Severe diarrhea can lead to dehydration, which is a serious issue and needs to be treated with rehydration with fluids and electrolytes. Chronic and severe diarrhea could be related to digestive disorders (e.g., lactose intolerance, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, celiac) or viral (e.g., norovirus), bacterial (e.g., clostridium difficile [C. diff.]), or parasites (e.g., giardia) Contact isolation is required when a client has or is suspected to have infectious diarrhea. |

|

Appetite changes are common symptoms associated with the GI system. These changes can involve a decrease or increase in appetite (for foods or fluids), and can be physiologically or psychologically related. |

Have you had any recent appetite changes (such as decreased or increased appetite)? If the client’s response is affirmative, additional probes may include: Quality/quantity: Tell me about the changes? How bad have the changes been? Timing: When did these changes begin? Are the changes in appetite constant or intermittent? What was going on in your life when these changes began? Provocative/palliative: Is there anything that makes the appetite changes worse? Is there anything that makes the appetite changes better? Treatment: Have you treated the appetite changes with anything? Do you take any medications for it? Understand: Do you know what is causing the appetite changes or what they are related to? |

Changes in appetite can be a sensitive issue for some clients. Use a non-judgmental approach when asking questions, and use words that the client uses when asking additional probes (e.g., when did you begin feeling like not eating?). Prompt intervention is needed if a newborn is not eating, as adequate nutrition is important to growth and development, and they can also dehydrate easily. |

|

Other GI-related symptoms can include fatigue, unintended weight loss, fever, rectal pain/bleeding/pruritus, and lymph node swelling. |

Only ask one question at a time. For example: Have you experienced fatigue (appetite changes, unintended weight loss, fever, rectal pain/bleeding, lymph node swelling)? If the client’s response is affirmative, use variations of the PQRSTU mnemonic to assess the symptoms further. |

Keep in mind that many of these GI-related symptoms can be related to other body systems. Thus, these symptoms require further investigation to determine whether they are related to the GI system. You should assess the severity of rectal bleeding to determine whether prompt intervention is required. |

|

Personal and family history of GI conditions and diseases. As noted earlier, common issues associated with the GI system include dental cavities, acid reflux, ulcers, cancers, hepatitis, ascites, constipation, and hernias. |

Do you have any chronic conditions or diseases associated with your GI system? Do you have a familial history of conditions or diseases related to the GI system? If the client’s response is affirmative, begin with an open-ended probe: Tell me about the condition/disease? If the client has a personal history, additional probing questions might include: Timing: When did it occur? When were you diagnosed? Quality/quantity: How does it affect you? What symptoms do you have? Treatment: How is it treated? Do you take medication? Provocative/palliative: Is there anything that makes it worse? Is there anything that makes it better? Understanding: Do you have any concerns about how the condition or disease is affecting you? |

Some clients may not be familiar with the word gastrointestinal (GI). If so, use words such as the mouth, esophagus, stomach, liver, bowels/intestines. Some GI-associated diseases have a genetic component, but environmental and cultural factors (family traditions and personal practices) are more likely for many symptoms (e.g., diarrhea, constipation, hepatitis). |

Knowledge Bites

Blood can appear in the stool for various reasons; this requires a focused and prompt assessment so that you can attempt determine the cause. Start by asking when it began and what the client has noticed (e.g., colour, amount, associated symptoms).

- If the colour is bright red, this suggests active bleeding and is usually associated with the lower GI system, possibly related to the rectal area or the lower/distal portion of the colon. The objective assessment should begin by inspecting the perianal region to check for any bleeding around the anus, possibly caused by hemorrhoids.

- Sometimes the bleeding is difficult to notice because it is darker in colour. Melena is black sticky stool (often referred to as tar-like) and can be caused from bleeding higher in the GI tract. You might visualize dark brown or black specks in stool resembling coffee grounds.

- If the stool is red and resembles a jelly-like substance, this could indicate intussusception. It is a serious GI condition in which a part of the intestine folds into itself, causing obstruction of the bowel and constriction of blood supply. It is rare in adults, but a common cause of intestinal obstruction in infants and toddlers. It is often associated with severe abdominal pain, lethargy, nausea, and vomiting.

Sometimes what looks like blood in the stool is not actually blood. Diet (e.g., beets, black licorice) and certain medications (e.g., iron medications) can change the colour of stool.

Some blood is not visible to the naked eye. This is called “occult blood” and can only be determined by testing a stool sample for blood. In Ontario, a fecal immunochemical test (FIT) is routinely recommended when someone is at “average risk” (over age 50 and no first-degree relative diagnosed with colorectal cancer) or at “increased risk” (family history of colorectal cancer) (Cancer Care Ontario, n.d.).

If you identify blood in the stool, your action should be based on its severity and associated symptoms. Act promptly if the amount of blood is concerning or if the client shows signs of clinical deterioration. It’s always best to do a primary survey to determine the potential of deterioration.

Priorities of Care

Certain symptoms associated with the GI system are cues that require action. Urgent intervention is required when the cues suggest clinical deterioration or the potential for clinical deterioration. For example, urgent intervention is required with:

- New onset dysphagia (can be associated with stroke and/or can lead to complications).

- Severe diarrhea and/or vomiting (particularly with signs of dehydration or when vomiting indicates hematemesis).

- GI pain (may suggest angina) or right lower quadrant pain (may suggest appendicitis).

- GI pain in infants (may suggest intussusception).

If you encounter a cue that suggests clinical deterioration, ask a colleague to call the physician/nurse practitioner while you perform a primary survey and a focused objective assessment. For example, assess the client’s respiration rate, work of breathing, oxygen saturation, and then pulse, blood pressure, and temperature, followed by auscultation of lungs.

Any evidence of bleeding requires intervention. However, the severity (e.g., the amount and whether it is active bleeding) will determine how prompt the intervention needs to be. Additionally, when a care partner or parent indicates that an newborn/infant has had a decreased number of wet diapers, you should conduct further assessment as this could be a sign of dehydration.

Activity: Check Your Understanding

References

Ahmed, N. (2005). 23 years of the discovery of Helicobacter pylori: Is the debate over? Annals of clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-0711-4-17

Cancer Care Ontario (n.d.). Guidelines & advice: Colorectal cancer screening recommendations summary. https://www.cancercareontario.ca/en/guidelines-advice/cancer-continuum/screening/resources-healthcare-providers/colorectal-cancer-screening-summary

Kusters, J., van Vliet, A., & Kuipers, E. (2006). Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 19(3), 449-490. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00054-05