9.3 Brief Scan: Respiratory System

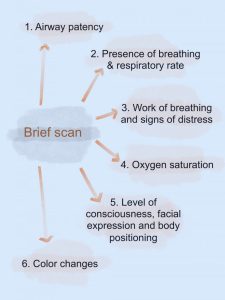

A brief scan (see Figure 9.6) involves inspection of the client’s breathing and includes elements of the primary survey (ABCCS). This assessment helps you quickly recognize cues of clinical deterioration, specifically signs of respiratory distress, and may influence your decision on whether immediate action is required. The steps of a brief scan are prioritized in order of importance. For example, you need to assess whether an airway is patent (i.e., not obstructed) before you assess presence of breathing and respiratory rate.

Guided by the primary survey (ABCCS), steps of the brief scan of the respiratory system include assessing respiratory effort and signs of respiratory distress:

Step 1. Assess airway patency

- Determine whether there is an open airway or the presence of obstructive airway symptoms (e.g., secretions [mucus, blood, vomit], snoring, stridor, difficulty breathing, coughing, drooling, wet-sounding voice, unable to speak). Partial or complete obstruction of airways is commonly associated with foreign objects, inflammation, and direct injury/trauma to the airway. An obstructed airway is a first-level priority of care because it affects oxygenation and can lead to clinical deterioration.

Step 2. Assess presence of breathing and respiration rate

- First, assess the presence of breathing and eupnea, which is normal automatic breathing with a regular rhythm. Apnea is the cessation of breathing and can be permanent or intermittent. It can result in severe hypoxia, and can be associated with respiratory depression from certain medications, and can also involve sleep apnea when breathing stops intermittently.

- If breathing is present, count the rate for 30 seconds if the rhythm is regular and one minute if it is irregular. Are there signs of bradypnea or tachypnea? See Table 9.2 for normal respiratory rates.

| Age | Rate (breaths per minute) |

|---|---|

| Newborn to one month | 30 to 60 |

| One month to one year | 26 to 60 |

| 1 to 10 years | 14 to 50 |

| 11 to 18 years | 12 to 22 |

| Adult and older adult | 12 to 20 |

Step 3. Assess work of breathing and signs of respiratory distress.

- Is the breathing silent or noisy? Do you hear wheezing or stridor? Normal breathing is silent. Noisy breathing with wheezing or stridor is a sign of distress.

- Do you observe nasal flaring? (This is a common symptom of respiratory distress, particularly in infants and young children. However, keep in mind that newborns are nose breathers. Additionally, air does not enter the lungs until birth so the newborn may be congested and you may observe nasal flaring.)

- Do you observe use of the accessory muscles (i.e., sternomastoid and trapezius) and intercostal tugging/pulling/retractions? Unobstructed breathing with no respiratory distress should be quiet with no observable use of accessory muscles or intercostal tugging. Observable use of accessory muscles and intercostal tugging are signs of distress.

- Do you observe any abnormal patterns of breathing? One example of an abnormal pattern of breathing is agonal breathing; it involves an irregular rhythm with gasping and is a sign that a person is near death.

Step 4. Assess oxygen saturation.

- Is the oxygen saturation level below 95 to 97%? Although 97 to 100% is the normal range for oxygen saturation levels, older individuals may have a slightly lower saturation (also, see Knowledge Bites for information about when lower oxygen saturations are acceptable in certain populations). Keep in mind that a saturation below 97% in children should always be further investigated.

- Nail polish should be removed before assessing oxygen saturation with a pulse oximeter on the finger.

- The accuracy of pulse oximetry can be affected by low perfusion states (e.g., vasoconstriction or low cardiac output). If you suspect low perfusion or you are getting a weak signal on the finger, use a pulse oximeter that snaps on the ear or can be taped to the forehead. These approaches to measuring oxygen saturation are best when a client has artificial nails.

Contextualizing Inclusivity: Pulse Oximetry

Oxygen saturation measured with pulse oximetry is sometimes overestimated in a client with dark skin: oxygen saturation may appear higher than it really is. If a client indicates that they are short of breath, but this is not reflected on the pulse oximeter, believe the client and assess further. It is always best to assess further when the client’s signs and symptoms do not align with the pulse oximetry.

Step 5. Assess level of consciousness, facial expression, and body position for signs of respiratory distress.

- Does the client have an altered level of consciousness and confusion? Normally, clients should be alert and oriented.

- Does the client show signs of agitation such as wide eyes and grimacing? Normally, a client should have a relaxed facial expression.

- Is the client showing signs of distress including hunched over/tripod position or unable to sit up? A client should normally be in a relaxed posture, while those in respiratory distress often shift into a tripod position: leaning forward with hands and/or forearms resting on their legs or another surface such as a table.

Step 6. Assess color changes (and fingernails for clubbing and testing capillary refill)

- Are there signs of cyanosis or pallor in the lips, mucous membranes, fingernails, or conjunctiva? Cyanosis and pallor result from hypoxemia, and can have many causes.

Contextualizing Inclusivity: Assessing Color Change

Cyanosis: This is best seen in areas with rich vasculature and thin overlying dermis: mucous membranes/lips, conjunctiva, and extremities (fingernails). In people with darker skin, cyanosis can appear as a gray/white shade around the lips and the conjunctiva can appear as a gray/bluish shade, while people with yellowish tones to their skin can have a grayish/green shade (Lewis, 2020; Sommers, 2011). In people with lighter skin, cyanosis appears as a dusky bluish/purple shade (Lewis, 2020).

Pallor: In people with darker skin, this can appear as a gray shade to the mucous membranes/lips, nail beds, and skin, and a yellowish shade in people with lighter brown skin; it can be helpful to look at the palms of people with dark skin when assessing for pallor as they tend to be paler (Lewis, 2020). In people with lighter skin, pallor can appear as a generalized pale discoloration to the skin, nail beds, and mucous membranes/lips. In people of all skin colors, the conjunctiva is normally a healthy pink due to the vascularity, but with pallor it will appear white or very pale pink (Mukwende et al., n.d.).

- While assessing fingernails, also assess for presence of clubbing. Clubbing is related to conditions that lead to chronic hypoxia and cause the nail angle to flatten to 180 degrees or more, the nail bed to soften and become spongy, and the fingertips distal to the distal interphalangeal joint to become enlarged. Normally, the nail angle is about 160 degrees with firm nail beds, and no enlarged fingertips. It is often assessed on the index finger, but in cases of early clubbing it may not have advanced to that digit, so it is best to assess the thumb first. To assess for the presence of clubbing:

- Ask the client to stick their thumb (or index finger) out so that it is parallel to the ground and view it at eye level (this is considered the profile sign).

- Inspect the nail angle at the intersection of where the nail base meets the skin (the angle should be about 160 degrees).

- Inspect for enlarged fingertips that look “bulb-like” (see Figure 9.7).

- Palpate the nail bed (it should be firm to touch).

- Test capillary refill on two or three fingernails of each hand. Start by applying pressure with your own finger to the client’s nail; this causes the nail to blanch (become pale in color). Apply the pressure for about 5 seconds and then release and observe the return in color. It should return within 3 seconds or less; a more sluggish return (more than 3 seconds) suggests that there may be issues with oxygenated blood perfusion, which might be caused by respiratory, cardiac, and/or peripheral vascular system issues.

Step 7. Note the findings.

- Normal findings might be documented as: “Patent airway, quiet breathing with no signs of respiratory distress. Alert. Oxygen saturations 98%. No color changes with translucent nails and pinkish undertone. No signs of clubbing. Capillary refill returns within 1–2 seconds.”

- Abnormal findings might be documented as: “Stridor present, nasal flaring and intercostal tugging, pallor noted around lips. Oxygen saturations 91%. Slow capillary refill at 4–5 seconds.”

Priorities of Care

A client who is in respiratory distress requires immediate intervention, especially if signs indicate an obstructed airway, increased work of breathing, an altered level of consciousness, and an oxygen saturation dropping below 92%. Stay with client and call for help (a senior nurse, physician, or nurse practitioner) if a client is in respiratory distress.

- If an airway is not patent, try to open the airway with a head-tilt-chin-lift and inspect the mouth and nose for obstructions.

- If oxygen saturations are low, try to wake the client if they are sleeping, sit them upright, and ask them to take a few deep breaths. Supplemental oxygen can be applied if there are standing orders on your unit.

You may need to keep the client in a supine position if you suspect that they are deteriorating quickly and may go into respiratory or cardiac arrest. Notify the critical care response team (CCRT) or call a code in this case. Bag-mask-ventilation may be needed if the client is in respiratory arrest.

If you suspect the client is choking, stay with the client and call for help while you place them in a high Fowler’s position. If they are able to, encourage them to cough and clear their airway. You may need to suction the oral cavity and airway, if possible. If you suspect a complete obstruction, use your Basic Life Support Training skills.

Knowledge Bites

Lower oxygen saturation levels (between 88 to 92%) are acceptable for those with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD).

In a healthy person without COPD, the strongest stimulus for the normal respiratory drive is hypercapnia (increased carbon dioxide, CO2, in the blood). This means that a person is stimulated to breathe when there are high CO2 levels in their blood.

In contrast, a person with COPD has a reduced capacity to exhale carbon dioxide, leading to hypercapnia (increased CO2 in the blood). As a result, there is a shift in the normal respiratory drive: the respiratory drive becomes a hypoxic drive, meaning that low oxygen is the primary stimulus to breathe. This means that low oxygen levels stimulate respirations as opposed to hypercapnia because a person with COPD is a CO2 retainer (i.e., they retain CO2 in their lungs). Therefore, when performing a brief scan, consider oxygen saturation levels in the context of existing conditions and be cautious about applying oxygen when a client’s oxygen saturation is lower than normal, particularly if the client has COPD.

References

Lewis, G. (2020). Identifying AEFI in diverse skin color. https://mvec.mcri.edu.au/references/identifying-aefi-in-diverse-skin-colour/

Mukwende, M., Tamony, P., & Turner, M. (n.d.). Mind the gap: A handbook of clinical signs in black and brown people. (1st edition). https://litfl.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Mind-the-Gap-A-handbook-of-clinical-signs-in-Black-and-Brown-skin.-first-edition-2020.pdf

Sommers, M. (2011). Color awareness: A must for patient assessment. American Nurse. https://www.myamericannurse.com/color-awareness-a-must-for-patient-assessment/