12.8 Inspection and Auscultation of Abdominal Vasculature **This is an advanced skill

Inspection and auscultation of abdominal vasculature is best performed with the client in a supine position with their head on a pillow. You will be assessing the area over the abdominal aorta, renal arteries, iliac arteries, and femoral arteries (Figure 12.11). Draping is important because you will need to expose the abdomen and groin area.

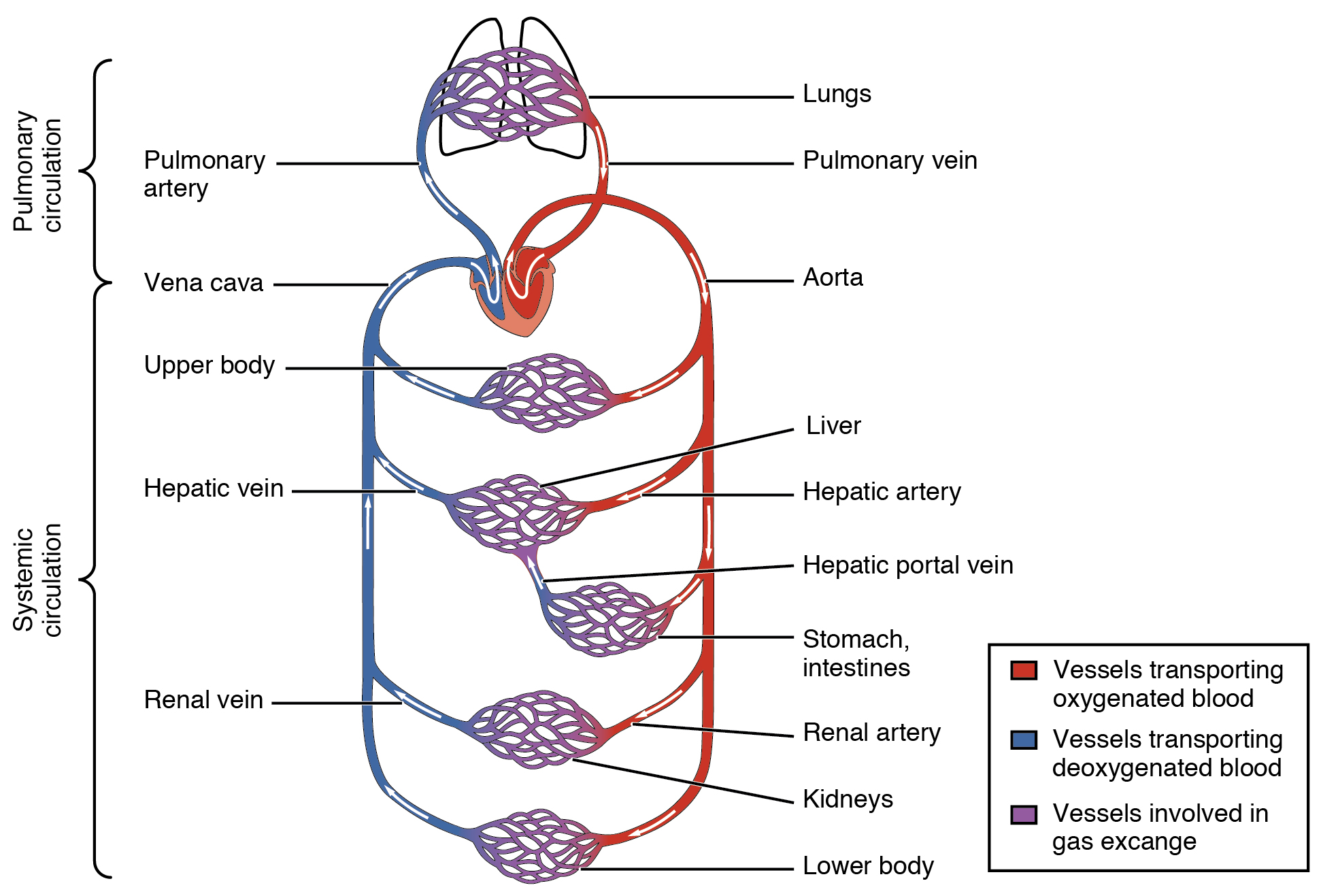

The peripheral vascular system (PVS) is a continuous network of blood vessels that carry oxygenated blood away from the heart to the periphery and carry deoxygenated blood back to the heart and to the lungs for reoxygenation. This system is important in the perfusion and oxygenation of tissues in the periphery. If this system is not functioning properly, perfusion issues can arise including hypoxia and tissue damage.

Assessment of the PVS provides information about the functioning of this system and cues that may require action.

Peripheral Vascular System Components

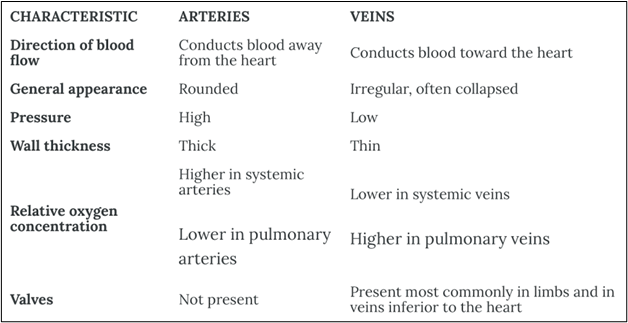

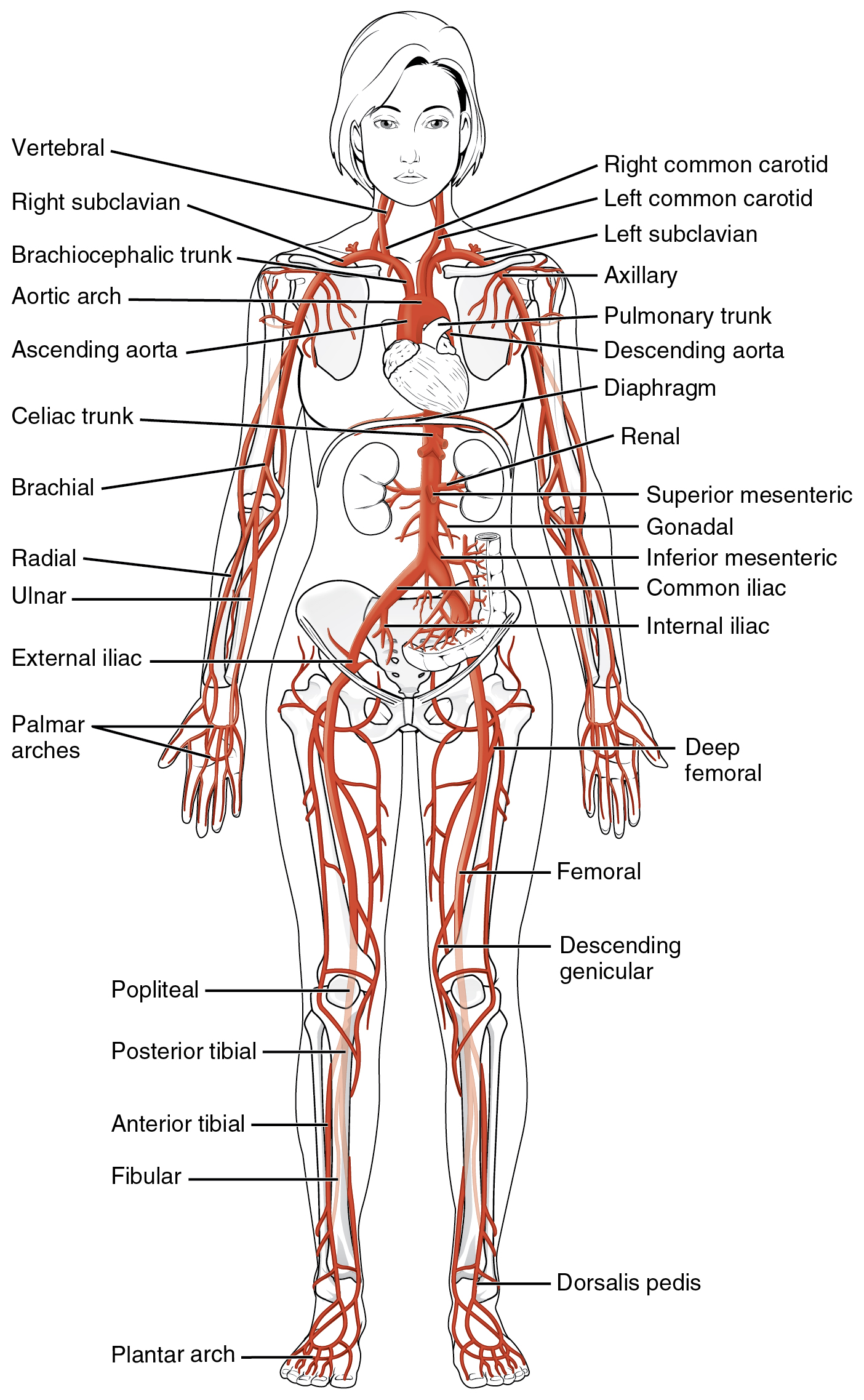

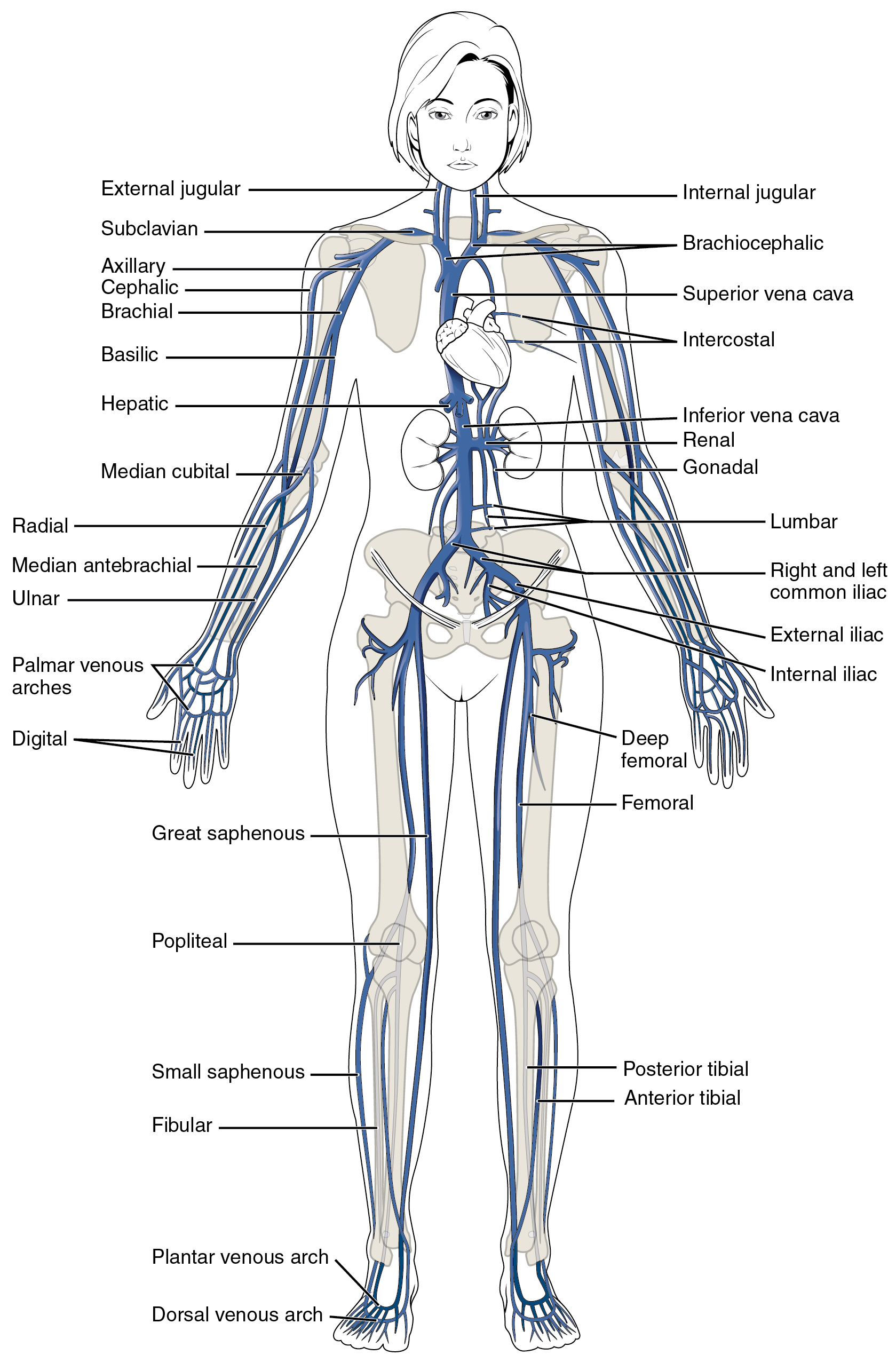

The main components of the PVS (see Table 1 and Figures 1 and 2) include:

- Arteries: vessels that carry blood away from the heart to the periphery. Blood in the arteries is referred to as arterial blood. The multiple layers of the arteries are strong and elastic and can dilate (expand in circumference) and recoil (decrease or return to normal size) in relation with cardiac systole and diastole. These high-pressure vessels dilate when the heart contracts and pumps blood out into them and then recoil to push blood through the arteries, creating a wave of blood through the vessels (felt as a pulse).

- Veins: vessels that carry blood back to the heart from the periphery. Blood in the veins is referred to as venous blood. The walls of these vessels are thin in comparison to arteries but have good stretching capacity, so they can acclimate to larger volumes of fluid (blood) when needed. Veins are low-pressure vessels because they are further away from the heart than arteries. Cardiac systole (contraction of the heart) does not assist with the forward movement of venous blood the way it does with arterial blood. Rather, forward movement of venous blood is mainly achieved through contraction of the skeletal muscles surrounding these veins and intraluminal valves in the veins that maintain unidirectional blood flow and prevent backward flow of blood.

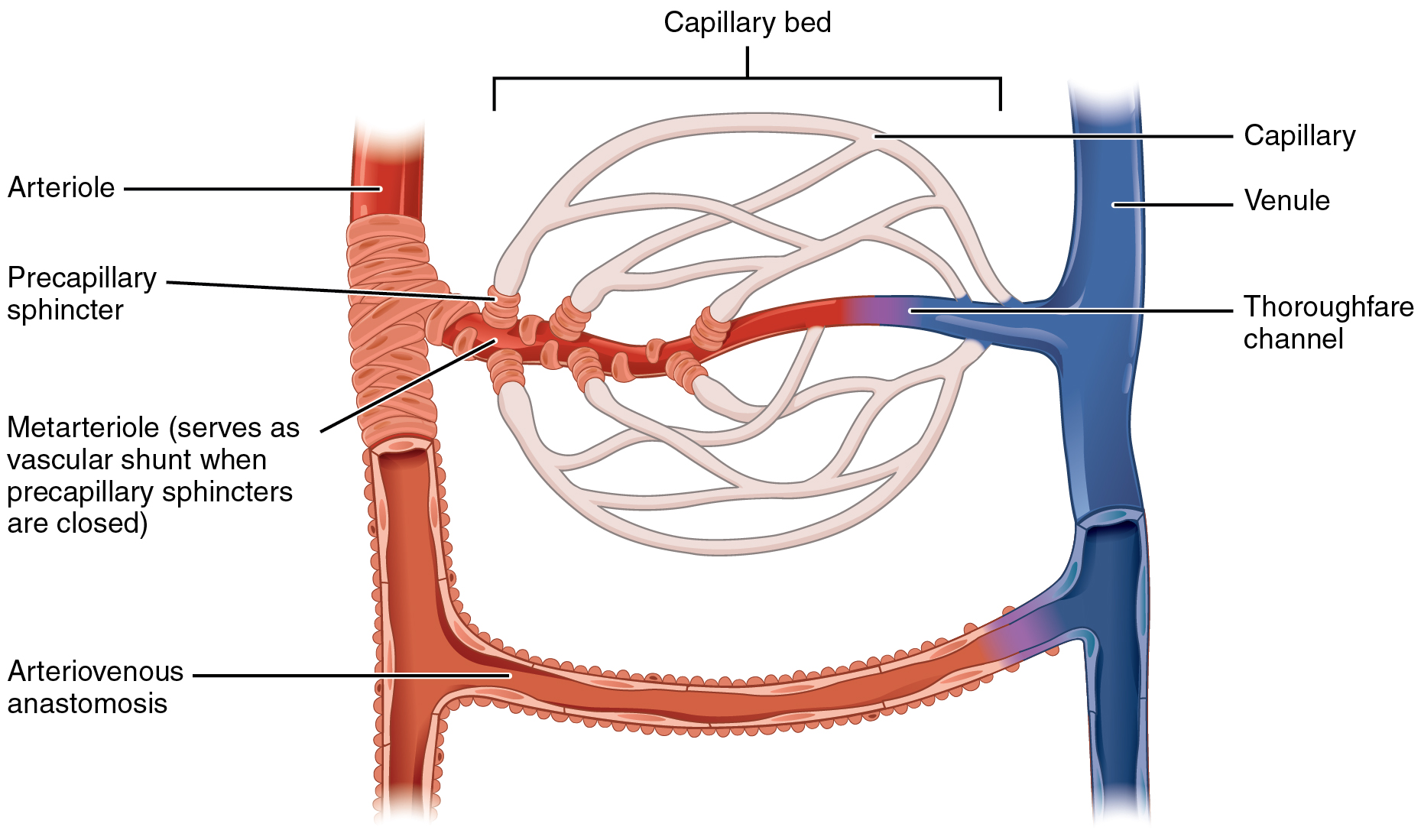

- Capillaries: small blood vessels that connect the arteries to the veins. Their main function is to facilitate the exchange of materials between blood and body tissues (e.g., muscles, kidneys, liver). They deliver blood and its components (nutrients and oxygen) to tissues throughout the body and transport waste products.

You have already learned about the anatomy and physiology of the PVS assessment: see this video for a quick overview: https://youtu.be/v43ej5lCeBo

Table 1: Comparison of arteries and veins. (Image from Anatomy and Physiology [on OpenStax] by Betts et al., used under a CC BY 4.0 international license. Download and access this book for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction)

Figure 1: Peripheral vascular system anatomy. (Image from Anatomy and Physiology [on OpenStax] by Betts et al., used under a CC BY 4.0 international license. Download and access this book for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction)

Figure 2: Capillaries. (Image from Anatomy and Physiology [on OpenStax] by Betts et al., used under a CC BY 4.0 international license. Download and access this book for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction)

Clinical Tip

The PVS is interconnected with many other body systems, so it is rarely assessed in isolation. When attempting to make sense of cues, nurses commonly assess other body systems including cardiovascular, integumentary, lymphatic, and musculoskeletal. See Figure 3 for related systems. For example, the PVS might be assessed along with a cardiovascular assessment to assess perfusion and also with the musculoskeletal system to assess potential blood flow interruptions. The PVS is also closely related to the lymphatic system and connected via the capillaries. In addition, many PVS conditions affect the skin, thus the integumentary system is often assessed.

Figure 3: Pulmonary and systemic circulation.

(Image from Anatomy and Physiology [on OpenStax] by Betts et al., used under a CC BY 4.0 international license. Download and access this book for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction)

Activity: Check your Understanding

A 48-year-old client comes to the clinic with back pain. They report feeling pain in their back after moving some boxes. Yesterday their back spasmed as they tried to get out of bed, and now they’re unable to bend over to tie their shoes without feeling pain. The client has a history of back pain for the past 10 years. They play rugby and go to cross-fit exercises 2x/week. Due to the spasms, they are unable to do anything or go out and are feeling useless. Vital signs: blood pressure 124/78 mm Hg, pulse 98 beats per minute, respirations 20 breaths per minute and shallow, oxygen saturation 98%, oral temperature 36.9 degrees Celsius, BMI: 26. Upon a brief inspection, the client's trapezius muscles are elevated and tense, and their posture is leaning slightly forward to the left while walking slowly. Client slowly sat down in the chair with their face grimacing and using pursed lip breathing.

The client has been diagnosed with strained lower back muscles and inflammation along the L4-5. The client is being discharged and requires health teaching. Identify which health teaching strategies are required by dragging and dropping each strategy in the Indicated or Not Indicated columns.

Steps for assessing the abdominal vasculature include:

Step 1: Observe for pulsations over the areas of the abdominal vasculature. Use tangential lighting with a penlight; this will help highlight any small imperfections/shadows, which accentuate visible pulsations.

Step 2: Auscultate over the abdominal vasculature (see Figure 12.11 and Video 4) using the bell of a cleansed stethoscope. Use slightly firmer pressure than when you use the diaphragm over the lungs or intestines. Listen for vascular sounds related to the flow of the blood through the arteries. Placing your stethoscope in each location for about 2-3 seconds is usually sufficient.

Step 3: Note the findings.

Video 4: Auscultation of the abdominal vasculature [1:27]

Priorities of Care

If you hear a bruit, do not palpate the area. Ask if the client has experienced any recent pain in their chest, back, abdomen, or groin, and if they have ever been diagnosed with an aneurysm. You should also complete a primary survey (ABCCS) and measure blood pressure in both arms. Notify the physician and nurse practitioner of the findings. Until an aneurysm is ruled out or assessed, it is best to keep the client in bed, at rest, and under continuous monitoring.

Activity: Check Your Understanding