7.6 Objective Assessment

An objective MSK assessment is generally completed after the subjective assessment. If the client shows signs of clinical deterioration, such as respiratory distress, you should focus the interview portion on pertinent questions and proceed directly to the objective assessment and associated interventions. For example, a fractured rib or vertebral fracture or a fracture that has severed circulation requires urgent intervention.

Be aware of the environmental temperature in the room and the temperature of your hands. Room temperatures are not easily modified, so try to limit exposing the client’s body parts and keep them covered with their clothes or sheet/blanket until you need to assess that body part. This also follows a trauma-informed approach and maintains the client’s dignity and limits exposing them unnecessarily. If a stethoscope is needed, warm your hands and stethoscope before placing them on the client’s body.

The objective assessment of the MSK system involves a brief scan and a focus on inspection, palpation, range of motion (ROM), and manual muscle testing (MMT), and sometimes auscultation, depending on the affected area (see Table 7.2). Compare the body bilaterally throughout the assessment. Assess the unaffected side first for comparison with the affected side, and when a joint is affected, at the minimum, assess above and below the joint. However, it is important to note that some causes of joint pain can go beyond the joint above and joint below.

The sequential order of the objective assessment is typically based on minimizing position changes and using a cephalocaudal (head to toe) or proximal to distal approach. Although certain positions are suggested, you may need to adapt the position if a client is not able to stand or sit up. Do not conduct ROM or muscle testing if the subjective assessment and/or inspection and palpation suggest trauma to the neck or back, or a bone fracture.

| MSK Assessment | Clinical Tips |

| Inspection involves systematic observation with a focus on muscles, bones, and joints. Depending on the areas inspected, this may include color, swelling, masses, deformities, and asymmetry. Observed deformities may include subluxation (when a bone is partially dislocated within a joint) or a complete dislocation in which the articular surface of two bones are no longer aligned or connected. You also need to assess the surrounding skin condition and presence of bleeding with open fractures and whether you observe any involuntary muscle contractions (e.g., twitching, spasms). | Remember to compare findings bilaterally and further assess discrepancies, asking additional subjective questions when required.

Any abnormal findings noted upon inspection should be further assessed with palpation. You should assess for the presence of muscle atrophy/wasting (loss of muscle mass and tone) in clients who have suspected musculoskeletal conditions and mobility issues. It is best evaluated by comparing the client’s muscle mass and tone to their baseline (i.e., their normal composition). |

| Palpation involves applying your hands to assess temperature, pain, masses, swelling, deformities, palpable fluid, and size and contour of muscles. You can palpate the affected area if the client notes or you observe any involuntary muscle contractions (e.g., twitching, spasms). | Assess the unaffected side first to compare it to the affected side.

Use the dorsal aspect of your hands to assess for temperature, because it is most sensitive to temperature changes. For palpation, use your finger pads as they are densely innervated. Your thumb will often be used along with your fingertips when assessing joints. A synovial joint does not normally have palpable fluid. To learn more details about palpation techniques, review the Physical Examination Techniques: A Nurse’s Guide open educational resource. |

| Range of motion (ROM) refers to a joint’s mobility: can it stretch to its fullest extent? You should become familiar with the normal ROM of each joint. A client’s baseline also is important so that you can evaluate their progress over time.

When assessing, make note of:

When performing ROM exercises, encourage the client to try to perform active ROM first, meaning that they move without assistance. If they are unable, help the client perform assisted active ROM, and then move to passive ROM as needed.

With all ROM, ensure the joint is still and stabilized. When performing assisted active or passive ROM, always support the client’s joint and maintain proper body alignment throughout the movement. It is appropriate to provide light pressure to fully test the full ROM of the joint, but you should never force a joint beyond its capacity, as this could cause damage. |

It is helpful to demonstrate the movement so that the client can mirror the motions you make. Before beginning, ensure the client’s body is aligned. As the client moves through the motions, ensure stability of the body part proximal to the joints.

Ideally, the client would perform ROM bilaterally at the same time in order to make comparisons. However, this is not possible with all joints such as the hips. Additionally, it may not be possible with clients who have mobility limitations and pain. The guidelines for ROM angles vary across the literature. We recommend using the ROM guidelines set out by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (1965) and Luttgens and Hamilton (1997), as they are most commonly used in practice. Typically, you will visually observe the angle of the joint. Note that this will be an estimate, which is an appropriate approach when doing a functional assessment of ROM. If a more accurate joint angle is needed (e.g., fitting for a wheelchair), you may require a goniometer, which is a tool that measures the angle of a joint. ROM can be affected by several factors including the person’s typical use of the joint and their age. New onset of limited ROM is a concern and is a cue that requires further investigation. |

| Manual muscle testing (MMT) evaluates the body’s capacity to innervate muscle strength. This can reveal neurologic deficits and help you evaluate their response to treatment of neuromuscular conditions. Essentially, you are evaluating the muscle strength resistance against the force of the assessor (i.e., the nurse).

Another method to assess a client’s muscle strength is a functional test. This kind of test assesses performance during activities of daily living; examples include the 30 Seconds Sit to Stand test or the Timed Up, Go (TUG) test. |

MMT can be evaluated in several ways. Check with the unit policy to see if there is a preferred approach. Keep these tips in mind when performing MMT:

|

Contextualizing Inclusivity

When assessing the MSK, you will need to assist the client into various body positions. Try to reduce the number of changes in body position, particularly for older clients and clients with physical disabilities who may have difficulty and possibly reduced strength to change positions. If you are assessing a newborn or young child, you can ask someone (e.g., care partner, health care provider, parent) to help hold and reposition the client on the exam table or in their lap while you conduct the assessment.

Knowledge Bites

Synovial joints have a small amount of fluid in the cavity between the articulating joints, but this fluid should not be palpable. Palpable fluid is a joint effusion, which refers to an accumulation of excess fluid. When palpating, it feels soft and moveable, and is sometimes associated with warmth, redness, and pain. The cause of effusions varies, but can be associated with infection, inflammation, and injury. Effusions are considered in the context of other cues, the severity, and potential causes. Treatment may be as simple as rest, ice or heat, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications. Depending on the cause and severity, other treatments may include antibiotics, arthrocentesis, and surgery.

References

American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Joint Motion: Method of Measuring and Recording. Chicago: AAOS; 1965.

James, M. (2007). Use of the Medical Research Council Muscle Strength Grading System in the Upper Extremity. The Journal of Hand Surgery (American Ed.), 32(2), 154–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2006.11.008

Luttgens, K. & Hamilton, N. (1997). Kinesiology: Scientific Basis of Human Motion, 9th Ed., Madison, WI: Brown & Benchmark.

Medical Research Council. Aids to the investigation of peripheral nerve injuries (2nd ed.), Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, London (1943).

Naqvi, U. Muscle strength grading. InStatpearls [Internet] 2019 May 29. StatPearls Publishing. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK436008/ (last accessed 7.1.20)

Schmitt, W.H., Cuthbert, S.C. Common errors and clinical guidelines for manual muscle testing: “the arm test” and other inaccurate procedures. Chiropractic and Manual Therapies 16, 16 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-1340-16-16

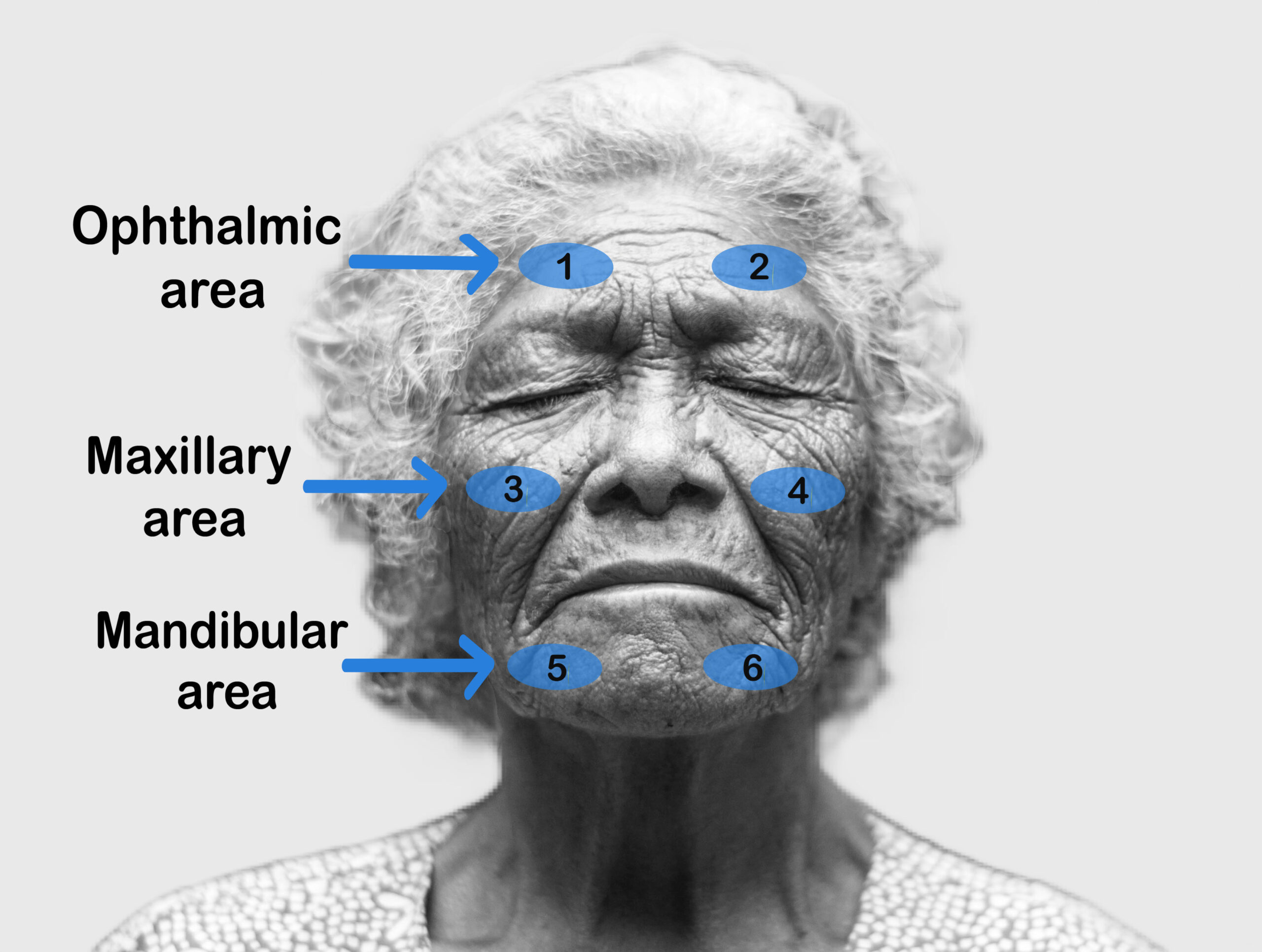

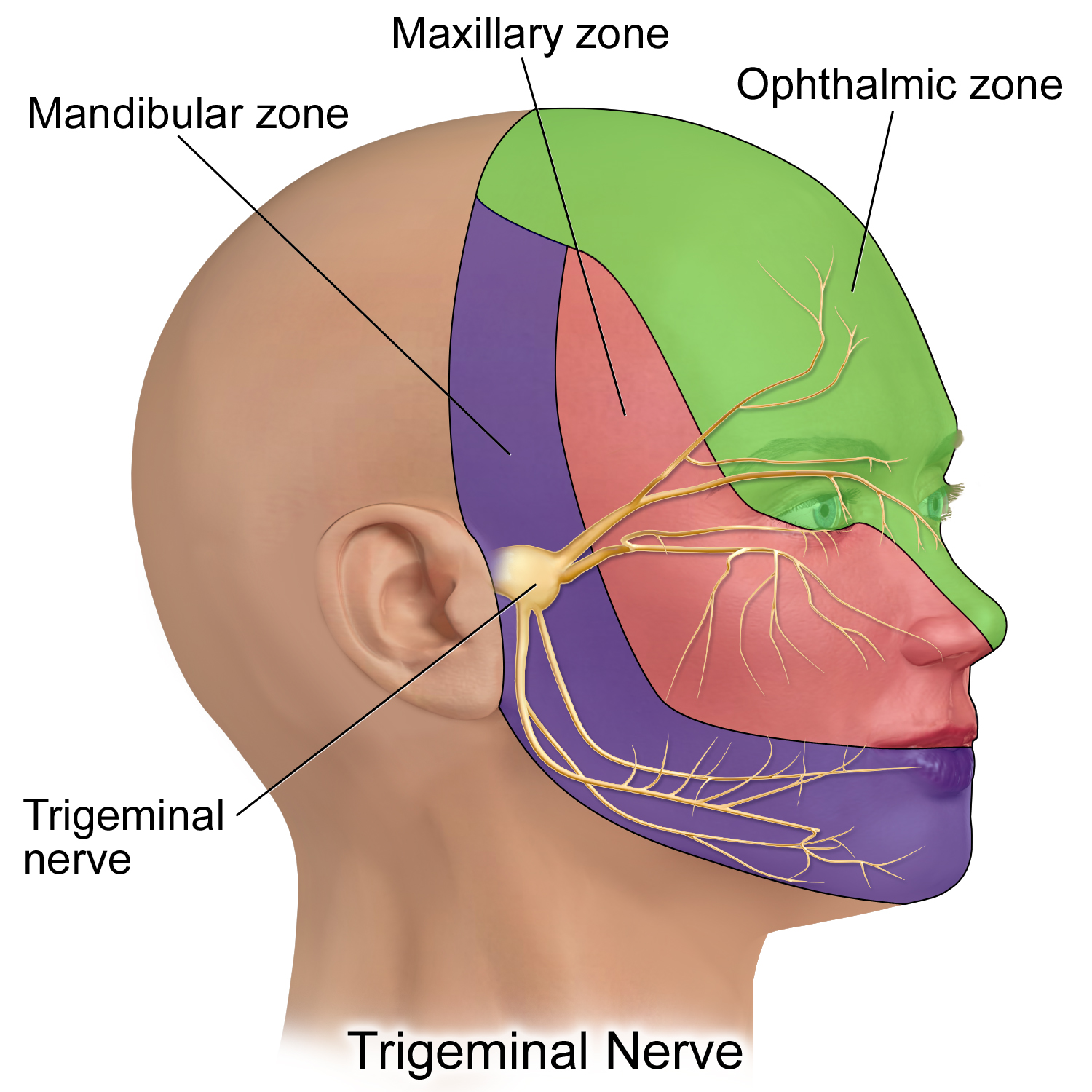

- Sensory function testing of CN V - Cotton ball: Explain to the client that you want them to close their eyes, that you will lightly touch areas on their face with a cotton-tipped applicator or cotton ball, and that they should indicate when they feel you touch their face each time. When their eyes are closed, briefly touch one spot in the ophthalmic area, then wait 2 to 3 seconds, and then touch the other ophthalmic area (see Figure 13). After touching these two spots, ask the client if the sensation felt the same. Repeat the same test for the maxillary and mandibular areas. The objective is to evaluate the locations where the trigeminal nerves innervate (see Figure 14 and Video 7).

-

- Normally, a client should be able to indicate when their face is being touched in the ophthalmic, maxillary, and mandibular areas bilaterally and the sensation should feel similar.

- Abnormal findings include not being able to feel the touch on one or more locations or having decreased sensation on one side. If you observe any abnormal findings or need more information, you may repeat the test using a tongue depressor broken in half. Apply the rounded edge or sharp edge in each location and ask the client to differentiate between “rounded edge” or “sharp edge.” You may show them the round edge and sharp edge before beginning and brush both on their forearm so they know what each feels like.

Figure 13: Trigeminal nerve sensation areas. (Illustrated by Tayiba Rahman)

Figure 14: Sites of trigeminal nerve innervation. (CC-BY 4.0 by BruceBlaus: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=61465350)

Video 7: Sensory testing of trigeminal nerve (CN V).

- Sensory function testing of CN V - Corneal reflex: Test the corneal reflex ONLY in specific situations, such as suspected brain stem damage or CN V or CN VII lesions - typically, the corneal reflex should NOT be tested on a person who is healthy. The corneal reflex is facilitated by afferent sensory CN V and efferent motor CN VII. To test the right eye, stand on the client’s right side; if they are able to follow commands, ask them to keep their head still to use their eyes only to look up and away from you. Then, with a delicate wisp of a cotton ball, gently touch the edge of the cornea. Repeat this procedure for the left eye. Some healthcare professionals perform the test with a drop of sterile saline instead of a wisp of the cotton ball to avoid possible corneal abrasion. See Video 8.

- Normally, there will be bilateral blinking.

- Abnormal findings include unilateral or absent blinking.

Video 8: Corneal reflex.

- Motor function testing of CN V - Inspect and palpate: Inspect the temporalis and masseter muscles for symmetry. Next, ask the client to clench their teeth while you palpate the temporalis and masseter muscles on both sides simultaneously along the upper and lower jaw.

- Normally, the muscles are equal bilaterally in size.

- Abnormal findings include asymmetrical muscle mass or atrophy.

- Motor function testing of CN V - Range of motion: Ask the client to open and close their mouth a bit slower than usual and then protrude and retract the lower jaw (move outwards and back inwards).

- Normally, these movements should all be symmetrical.

- Abnormal findings include asymmetrical movement.

- Motor function testing of CN V - Manual muscle testing: Perform manual muscle testing of the jaw. Ask the client to keep their head still and clench their teeth, and then place your thumbs on their chin with your fingers toward the back of the neck. With your thumbs, attempt to pull down their lower jaw. Then, ask them to open their mouth and resist your force (i.e., not let you push their jaw closed) while you apply upward pressure on their chin; to do so, place your fingers on their chin applying upward pressure and your other hand on the top of their head (see Video 9).

- Normally, the client should be able to resist your force, demonstrating good strength.

- Abnormal findings include decreased or no resistance in which the client cannot resist jaw opening unilateral or bilateral, or is unable to keep the jaw open, or the jaw deviates to one side.

Video 9: Manual muscle testing of the jaw.

- Note the findings:

- Normal findings might be documented as: “Trigeminal nerve test: sensations intact on ophthalmic, maxillary, and mandibular areas bilaterally. Temporal and masseter muscles equal in size, symmetrical movement observed with ROM. Client able to resist force on the jaw. Corneal reflex present bilaterally.”

- Abnormal findings might be documented as: “Trigeminal nerve test: no sensations felt on ophthalmic, maxillary, and mandibular areas bilaterally, temporal and masseter muscles atrophy bilaterally, no muscle strength in jaw, corneal reflex absent bilaterally.”

1. Motor function testing—facial asymmetry: Observe for facial asymmetry such as flattening of nasolabial fold, lack of wrinkles on forehead, drooping of the eyebrow, or decreased or absent blinking.

- Normally, there is no asymmetry and the client is able to blink.

- Abnormal findings include decreased blinking, flattening of nasolabial fold, asymmetry of eyebrows with one drooping (see Figure 13.20).

2. Motor function testing—facial muscle movement: Explain to the client that you will ask them to move their facial muscles in different positions. It is simplest if you demonstrate the movement and ask them to mimic it. Observe the client for movement and symmetry of movement (see Video 10).

- Move eyebrows upwards and crease the forehead.

- Smile while showing teeth.

- Puff out cheeks with air and hold, while you press gently on the cheeks in and out 2 to 3 times.

- Close eyes and keep them closed, while you try to spread them open with your index fingers on the upper orbital bones and thumbs on the lower orbital bones.

- Normally, the client should be able to perform all movements symmetrically, should be able to keep cheeks puffed out when you press on them, and should be able to keep their eyes closed while you try to open them.

- Abnormal findings include lack of movement, asymmetrical movement, inability to keep cheeks puffed out, and inability to keep eyes closed.

Video 10: Facial movements.

3. Sensory Sensation: To test taste related to CN VII, use a familiar substance such as sugar or salt, but do not tell the client what the substance is. Place the substance in a small amount of water and stir it with a cotton swab until it dissolves. Ask the client to open their mouth, then you will place the swab on the dorsal anterior third of the tongue (not on the tip of the tongue). Ask the client to identify the taste.

- Normally, the client should be able to identify the taste or substance.

- Abnormal findings include inability or reduced ability to identify the taste or substance or decreased taste.

4. Note the findings.

- Normal findings might be documented as: “Facial nerves testing: No asymmetry of eyebrows, blinking automatically, symmetrical movement of face. Client able to identify taste with cotton-tipped applicator soaked in sugar.”

- Abnormal findings might be documented as: “Facial nerves testing: Right eyebrow droops, client unable to wrinkle forehead or raise right eyebrow. Client unable to identify sweet taste of cotton-tipped applicator soaked in sugar.”

Testing can begin with the client sitting on the exam table. Before testing the vestibulocochlear nerves, ask the client about any history of impaired hearing and use of hearing devices. If the client has a hearing aid, they should keep it on.

- General ability: Begin by noting the client’s general ability to hear you throughout your ongoing assessment process. For example, have you noticed any difficulties in hearing as manifested by leaning forward, lip reading, or consistently asking you to repeat what you say?

- Whisper voice test: this test also helps evaluate the cochlear nerve. Tell the client that you are going to whisper a mixture of three numbers and letters and you want them to repeat what you say. Ask them to look straight forward, place their index finger on the tragus of the right ear, push the tragus in, and move their finger over the tragus in a circular motion until you ask the client to stop. Stand on their left side (slightly behind them and about an arm’s length away) to test the left ear. Take a breath in, and as you breathe out, whisper a mixture of three numbers/letters (e.g., 8, E, 4). The client should repeat what you say. If they don’t, whisper another set of three numbers/letters (e.g., 2, K, 10). Repeat on the opposite ear with a different set of numbers/letters. See Video 12.

- Normal findings are when the client can repeat what you say with both ears. If you need to repeat the set of numbers/letters on one ear (for a total of six), a normal finding is if the client is able to repeat at least half of the numbers/letters.

- Abnormal findings are when the client is unable to repeat the set of numbers/letters on one or both ears or unable to repeat at least half of them if repeated twice.

Video 12: Whisper voice test.

- Note the findings.

- Normal findings might be documented as: “Cochlear nerve test: With whispered voice test, client able to hear and repeat numbers and letters in both ears.”

- Abnormal findings might be documented as: “Client unable to hear and repeat numbers and letters whispered in left ear.”