7.1 Stress Response

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Healthcare is defined as the field concerned with the maintenance or restoration of the health of the body or mind. Although the goal is to maintain and restore, everyday in healthcare patients die. Death is not selective and does not only come to those who have lived long wonderful lives. We discussed in the last chapter that death comes in many forms to every age group: babies, children, teenagers, sons, daughters, mothers, and fathers. Those of us who entered healthcare to care for others often become attached to our patients, therefore the loss of a patient can be upsetting and stressful. Dealing with stress correctly will help you to be resilient through the loss of a patient and will allow you to stay strong to help others.

Stress Responses

For years researches believed that there was only one response available to deal with stress, Fight or Flight. This meant that the only options to deal with an everyday stress such as a late mortgage payment, missing assignment, or traffic accident would be to fight or run. Because this would be inappropriate, if we only have one stress response, we would have to learn to turn off the Fight or Flight response, or choose to avoid all types of stress. In healthcare, both of these options are impossible tasks. Due to recent research, it has been found that fleeing and fighting are not the only strategy that the body supports. The stress response has evolved, adapting over time to better fit the world we now live in.

Your stress response has the ability to help get you out of a burning building and engage with challenges, connect with social support, and learn from experience. Despite the fact that it feels like we do not choose our response, research shows we actually can! Choosing an appropriate stress response will allow you to be effective in healthcare and help others for the rest of your career. There are three main responses to stress, Fight or flight, Challenge, and Tend and Befriend response. So, how do we deal with the many stressors found in healthcare. It is important to understand the available stress responses and practice being mindful, or aware, that we have the strength to select the right one.

Fight or Flight

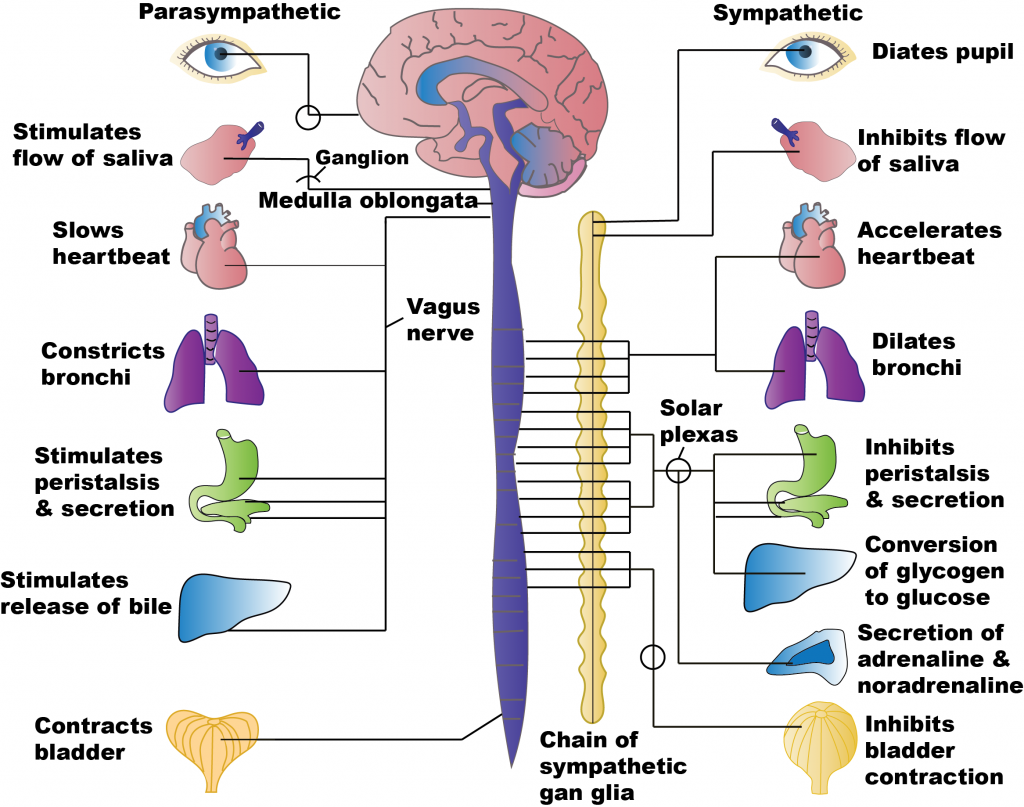

Stressors are any internal or external event, force, or condition that results in physical or emotional stress.[1] The body’s sympathetic nervous system (SNS) responds to actual or perceived stressors with the “fight, flight, or freeze” stress response. Several reactions occur during the stress response that help the individual to achieve the purpose of either fighting or running. The respiratory, cardiovascular, and musculoskeletal systems are activated to breathe rapidly, stimulate the heart to pump more blood, dilate the blood vessels, and increase blood pressure to deliver more oxygenated blood to the muscles. The liver creates more glucose for energy for the muscles to use to fight or run. Pupils dilate to see the threat (or the escape route) more clearly. Sweating prevents the body from overheating from excess muscle contraction. Because the digestive system is not needed during this time of threat, the body shunts oxygen-rich blood to the skeletal muscles. To coordinate all these targeted responses, hormones, including epinephrine, norepinephrine, and glucocorticoids (including cortisol, often referred to as the “stress hormone”), are released by the endocrine system via the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) and dispersed to the many SNS neuroreceptors on target organs simultaneously.[2] After the response to the stressful stimuli has resolved, the body returns to the pre-emergency state facilitated by the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) that has opposing effects to the SNS. See Figure 3.1[3] for an image comparing the effects of stimulating the SNS and PNS.

The purpose of the Fight or Flight response is to help you deal with danger, such as being inside a burning building. Your heart races, delivering oxygen, fat, and sugar to your muscles and brain, your breathing quickens: which delivers oxygen to the heart. This offers extraordinary physical abilities that make you ready for action. Your pupils dilate to let in more light, hearing sharpens, and your brain processes more quickly. All of these responses help you fight or run. While the “fight or flight” stress response equips our bodies to quickly respond to life-threatening stressors, exposure to long-term stress can cause serious effects on the cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, endocrine, gastrointestinal, and reproductive systems.[4] Consistent and ongoing increases in heart rate and blood pressure and elevated levels of stress hormones contribute to inflammation in arteries and can increase the risk for hypertension, heart attack, or stroke.[5]

While this response is essential for human survival, it is hard on the body and therefore cannot be the only stress response used for any areas of stress in our lives.

Challenge Response

The challenge response is an excellent response for many stressful situations or challenges, including stressful moments while caring for others. Adrenaline still spikes and the muscles and brain get more fuel. The response is a focused, but not fearful response, that allows the body to recover and learn from the stress. Top athletes, artists, surgeons, or gamers are not physiologically calm under pressure; rather, they have strong challenge responses.

The Challenge response is similar to exercise. Blood vessels relax to maximize blood flow and energy, the heart maintains a fast and strong beat, pumping even more blood than during the Fight or Flight response. Strong Challenge responses can be associated with superior aging, cardiovascular and brain health. Because the stressor is looked at as a challenge, you may feel anxious, excited, energized, enthusiastic, and confident. People who have strong Challenge responses will better learn resilience, suppresses fear, and enhance positive motivation during stress (McGonigal, 2016).

Tend and Befriend

The third response is Tend and Befriend. Oxytocin released by pituitary gland which calms the fear response and builds courage. This response will actually build and strengthen social bonds because you will talk with friends, family, and coworkers about stress. It will help you connect to others and the support will help recover from the stress. This response is actually good for cardiovascular health (McGonigal, 2016).

Mindfulness

Mindfulness is the ability to consciously choose the appropriate stress response for each situation. You are in a burning building, Fight or Flight. You are involved in the care of a crashing trauma patient, the Challenge response. You are faced with the death of a patient after caring for them for months, the Tend and Befriend response.

When experiencing a stressor, you should first acknowledge your feelings and not ignore that a stress is present. When feeling the physical symptoms such as a racing heart, recognize this is your body preparing you to deal with the stress, and does not mean you should automatically select the Fight or Flight response. Mindfully, choose the correct response when working in healthcare. Understand that there are many stressful moments while caring for others. Using the appropriate response will give you the tools you need to be courageous rather than fearful, and will allow you to recover from the stress of caring for others.

Mindfully choosing the correct stress response while dealing with the many difficulties in healthcare, will calm your fears and help you build and strengthen social bonds that will help build the resilience needed to work in healthcare. Please remember, important work is stressful, and healthcare is important work. Always remember why you chose this career and why it is important for you. The connection you maintain with friends family and coworkers

Stress Management

Effective stress management strategies can also be effective when dealing with stress and include the following[6],[7]:

- Set personal and professional boundaries

- Maintain a healthy social support network

- Select healthy food choices

- Engage in regular physical exercise

- Get an adequate amount of sleep each night

- Set realistic and fair expectations

Setting limits is essential for effectively managing stress. Individuals should list all of the projects and commitments making them feel overwhelmed, identify essential tasks, and cut back on nonessential tasks. For work-related projects, responsibilities can be discussed with supervisors to obtain input on priorities. Encourage individuals to refrain from accepting any more commitments until they feel their stress is under control.[8]

Maintaining a healthy social support network with friends and family can provide emotional support.[9] Caring relationships and healthy social connections are essential for achieving resilience.

Physical activity increases the body’s production of endorphins that boost the mood and reduce stress. Nurses can educate clients that a brisk walk or other aerobic activity can increase energy and concentration levels and lessen feelings of anxiety.[10]

People who are chronically stressed often suffer from lack of adequate sleep and, in some cases, stress-induced insomnia. Experts recommend going to bed at a regular time each night, striving for at least 7-8 hours of sleep, and, if possible, eliminating distractions, such as television, cell phones, and computers from the bedroom. Begin winding down an hour or two before bedtime and engage in calming activities such as listening to relaxing music, reading an enjoyable book, taking a soothing bath, or practicing relaxation techniques like meditation. Avoid eating a heavy meal or engaging in intense exercise immediately before bedtime. If a person tends to lie in bed worrying, encourage them to write down their concerns and work on quieting their thoughts.[11]

Mindfulness is a form of meditation that uses breathing and thought techniques to create an awareness of one’s body and surroundings. Research suggests that mindfulness can have a positive impact on stress, anxiety, and depression.[12] Additionally, guided imagery may be helpful for enhancing relaxation. The use of guided imagery provides a narration that the mind can focus in on during the activity. For example, as the nurse encourages a client to use mindfulness and relaxation breathing, they may say, “As you breathe in, imagine waves rolling gently in. As you breathe out, imagine the waves rolling gently back out to sea.”

WHO Stress Management Guide

In addition to the stress management techniques discussed in the previous section, the World Health Organization (WHO) shares additional techniques in a guide titled Doing What Matters in Times of Stress. This guide is comprised of five categories. Each category includes techniques and skills that, based on evidence and field testing, can reduce overall stress levels even if only used for a few minutes each day. These categories include 1) Grounding, 2) Unhooking, 3) Acting on our values, 4) Being kind, and 5) Making room.[13]

Nurses can educate clients that powerful thoughts and feelings are a natural part of stress, but problems can occur if we get “hooked” by them. For example, one minute you might be enjoying a meal with family, and the next moment you get “hooked” by angry thoughts and feelings. Stress can make someone feel as if they are being pulled away from the values of the person they want to be, such as being calm, caring, attentive, committed, persistent, and courageous.[14]

There are many kinds of difficult thoughts and feelings that can “hook us,” such as, “This is too hard,” “I give up,” “I am never going to get this,” “They shouldn’t have done that,” or memories about difficult events that have occurred in our lives. When we get “hooked,” our behavior changes. We may do things that make our lives worse, like getting into more disagreements, withdrawing from others, or spending too much time lying in bed. These are called “away moves” because they move us away from our values. Sometimes emotions become so strong they feel like emotional storms. However, we can “unhook” ourselves by focusing and engaging in what we are doing, referred to as “grounding.”[15]

Grounding

“Grounding” is a helpful tool when feeling distracted or having trouble focusing on a task and/or the present moment. The first step of grounding is to notice how you are feeling and what you are thinking. Next, slow down and connect with your body by focusing on your breathing. Exhale completely and wait three seconds, and then inhale as slowly as possible. Slowly stretch your arms and legs and push your feet against the floor. The next step is to focus on the world around you. Notice where you are and what you are doing. Use your five senses. What are five things you can see? What are four things you can hear? What can you smell? Tap your leg or squeeze your thumb and count to ten. Touch your knees or another object within reach. What does it feel like? Grounding helps us engage in life, refocus on the present moment, and realign with our values.[16]

Unhooking

At times we may have unwanted, intrusive, negative thoughts that negatively affect us. “Unhooking” is a tool to manage and decrease the impact of these unwanted thoughts. First, NOTICE that a thought or feeling has hooked you, and then NAME it. Naming it begins by silently saying, “Here is a thought,” or “Here is a feeling.” By adding “I notice,” it unhooks us even more. For example, “I notice there is a knot in my stomach.” The next step is to REFOCUS on what you are doing, fully engage in that activity, and pay full attention to whoever is with you and whatever you are doing. For example, if you are having dinner with family and notice feelings of anger, note “I am having feelings of anger,” but choose to refocus and engage with family.[17]

Acting on Our Values

The third category of skills is called “Acting on Our Values.” This means, despite challenges and struggles we are experiencing, we will act in line with what is important to us and our beliefs. Even when facing difficult situations, we can still make the conscious choice to act in line with our values. The more we focus on our own actions, the more we can influence our immediate world and the people and situations we encounter every day. We must continually ask ourselves, “Are my actions moving me toward or away from my values?” Remember that even the smallest actions have impact, just as a giant tree grows from a small seed. Even in the most stressful of times, we can take small actions to live by our values and maintain or create a more satisfying and fulfilling life. These values should also include self-compassion and care. By caring for oneself, we ultimately have more energy and motivation to then help others.[18]

Being Kind

“Being Kind” is a fourth tool for reducing stress. Kindness can make a significant difference to our mental health by being kind to others, as well as to ourselves.

Making Room

“Making Room” is a fifth tool for reducing stress. Sometimes trying to push away painful thoughts and feelings does not work very well. In these situations, it is helpful to notice and name the feeling, and then “make room” for it. “Making room” means allowing the painful feeling or thought to come and go like the weather. Nurses can educate clients that as they breathe, they should imagine their breath flowing into and around their pain and making room for it. Instead of fighting with the thought or feeling, they should allow it to move through them, just like the weather moves through the sky. If clients are not fighting with the painful thought or feeling, they will have more time and energy to engage with the world around them and do things that are important to them.[19]

Read Doing What Matters in Times of Stress by the World Health Organization (WHO).

View the following YouTube video on the WHO Stress Management Guide[20]:

Strategies for Self-Care

By becoming self-aware regarding signs of stress, you can implement self-care strategies to prevent compassion fatigue and burnout. Use the following “A’s” to assist in building resilience, connection, and compassion[21]:

- Attention: Become aware of your physical, psychological, social, and spiritual health. What are you grateful for? What are your areas of improvement? This protects you from drifting through life on autopilot.

- Acknowledgement: Honestly look at all you have witnessed as a health care professional. What insight have you experienced? Acknowledging the pain of loss you have witnessed protects you from invalidating the experiences.

- Affection: Choose to look at yourself with kindness and warmth. Affection and self-compassion prevent you from becoming bitter and “being too hard” on yourself.

- Acceptance: Choose to be at peace and welcome all aspects of yourself. By accepting both your talents and imperfections, you can protect yourself from impatience, victim mentality, and blame.

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Untitled image by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Shaw, W., Labott-Smith, S., Burg, M. M., Hostinar, C., Alen, N., van Tilburg, M. A. L., Berntson, G. G., Tovian, S. M., & Spirito, M. (2018, November 1). Stress effects on the body. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/body ↵

- Shaw, W., Labott-Smith, S., Burg, M. M., Hostinar, C., Alen, N., van Tilburg, M. A. L., Berntson, G. G., Tovian, S. M., & Spirito, M. (2018, November 1). Stress effects on the body. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/body ↵

- Shaw, W., Labott-Smith, S., Burg, M. M., Hostinar, C., Alen, N., van Tilburg, M. A. L., Berntson, G. G., Tovian, S. M., & Spirito, M. (2018, November 1). Stress effects on the body. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/body ↵

- Kelly, J. F., & Coons, H. L. (2019, October 25). Stress won’t go away? Maybe you are suffering from chronic stress. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/chronic ↵

- Kelly, J. F., & Coons, H. L. (2019, October 25). Stress won’t go away? Maybe you are suffering from chronic stress. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/chronic ↵

- Kelly, J. F., & Coons, H. L. (2019, October 25). Stress won’t go away? Maybe you are suffering from chronic stress. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/chronic ↵

- Kelly, J. F., & Coons, H. L. (2019, October 25). Stress won’t go away? Maybe you are suffering from chronic stress. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/chronic ↵

- Kelly, J. F., & Coons, H. L. (2019, October 25). Stress won’t go away? Maybe you are suffering from chronic stress. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/chronic ↵

- Kandola, A. (2018, October 12). What are the health effects of chronic stress? MedicalNewsToday. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/323324#treatment ↵

- This work is a derivative of Doing What Matters in Times of Stress: An Illustrated Guide by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO ↵

- This work is a derivative of Doing What Matters in Times of Stress: An Illustrated Guide by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO ↵

- This work is a derivative of Doing What Matters in Times of Stress: An Illustrated Guide by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO ↵

- This work is a derivative of Doing What Matters in Times of Stress: An Illustrated Guide by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO ↵

- This work is a derivative of Doing What Matters in Times of Stress: An Illustrated Guide by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO ↵

- This work is a derivative of Doing What Matters in Times of Stress: An Illustrated Guide by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO ↵

- This work is a derivative of Doing What Matters in Times of Stress: An Illustrated Guide by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO ↵

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2020, November 4). Doing what matters in times of stress: An illustrated guide [Video]. YouTube. Licensed in the Public Domain. https://youtu.be/E3Cts45FNrk ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

A vulnerable population is a group of individuals who are at increased risk for health problems and health disparities.[1] Health disparities are health differences linked with social, economic, and/or environmental disadvantages. Health disparities adversely affect groups of people who often experience greater obstacles to health based on individual characteristics, such as socioeconomic status, age, gender, culture, religion, mental illness, disability, sexual orientation, or gender identity.[2]

Examples of vulnerable populations are[3],[4]:

- The very young and the very old

- Individuals with chronic illnesses, disabilities, or communication barriers

- Veterans

- Racial and ethnic minorities

- Individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer (LGBTQ)

- Victims of human trafficking or sexual violence

- Individuals who are incarcerated and their family members

- Rural Americans

- Migrant workers

- Individuals with chronic mental health disorders

- Homeless people

Individuals typically have less access and use of health services, resulting in significant health disparities in life expectancy, morbidity, and mortality. They are also more likely to have one or more chronic physical and/or mental health illnesses.[5] Advancing health equity for all members of our society is receiving increased emphasis as a central goal of public health. Health equity is defined by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services as the “attainment of the highest level of health for all people” and that “achieving health equity requires valuing everyone equally with focused and ongoing societal efforts to address avoidable inequities, historical and contemporary injustices, and the elimination of health and health care disparities.”[6]

Examples of vulnerable populations and associated resources available to promote health equity and reduce health disparities are further described in the following sections.

Age and Developmental Status

Developmental status and age are associated with vulnerability. Children have health and developmental needs that require age-appropriate care. Developmental changes, dependency on others, and different patterns of illness and injury require that attention be paid to the unique needs of children in the health system. The elderly population also has unique health care needs due to increased incidence of illness and disability, as well as the complex interactions of multiple chronic illnesses and multiple medications.[7]

Children and the elderly are also vulnerable to experiencing neglect and abuse. Healthcare workers must be aware of signs of neglect and abuse and are legally mandated to report these signs.

Chronic Illness and Disability

Individuals with chronic illnesses and/or disabilities are more likely than the general population to experience problems in accessing a range of health care services. These vulnerable groups may also experience lack of coordination of care across multiple providers. In addition, individuals with specific chronic illnesses, such as individuals with mental illness or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), may face social stigma that makes it challenging to seek and/or receive appropriate health care.[8] See Figure 17.1[9] for an image of a disabled individual who is considered a member of a vulnerable population.

In addition to experiencing challenges in accessing appropriate health care, adults with disabilities report experiencing more mental distress than the general population. In 2018 an estimated 17.4 million (32.9%) adults with disabilities experienced frequent mental distress, defined as 14 or more reported mentally unhealthy days in the past 30 days. Frequent mental distress is associated with poor health behaviors, mental health disorders, and limitations in daily life.[10] The National Center on Health, Physical Activity and Disability (NCHPAD) is a public health resource center that focuses on health promotion, wellness, and quality of life for people with disabilities.

The Barrier-Free Health Care Initiative is a national initiative by the American Disability Association and the Offices of the United States Attorneys that supports people with disabilities. It legally enforces appropriate access to health care services, such as effective communication for people who are deaf or have hearing loss, physical access to medical care for people with mobility disabilities, and equal access to treatment for people who have HIV/AIDS. This nationwide initiative sends a collective message that disability discrimination in health care is illegal and unacceptable.

Visit the Barrier-Free Health Care Initiative to learn more.

Visit the National Center on Health, Physical Activity and Disability (NCHPAD) for additional wellness resources.

Veterans

A veteran is someone who has served in the military forces. Veterans have higher risks for mental health disorders, substance abuse, post-traumatic stress disorders, traumatic brain injuries, and suicide compared to their civilian counterparts. Medical records of veterans reveal that one in three clients was diagnosed with at least one mental health disorder.[11] Identifying and treating mental health disorders in veterans have the greatest potential for reducing suicide risk, but the reluctance in this population to seek treatment can make diagnosing and treating mental illness challenging. Nurses must be aware of their clients’ military history, recognize risk factors for common disorders, and advocate for appropriate health care services.[12] See Figure 17.2[13] for an image of a veteran.

Veterans Affairs (VA) provides health care and other benefits to individuals serving on active duty in the United States uniformed services. The Veterans Health Administration is the largest health care network in the United States with 1,255 health care facilities and serves nine million enrolled veterans each year. In addition to health care, benefits may include educational loans, home loans or housing grants, and life insurance. Nurses can refer clients who are veterans to the VA for more information about benefits.

Healthcare workers can also refer veterans and their family members to the National Alliance on Mental Health (NAMI) Homefront course. NAMI Homefront is a class for families, caregivers, and friends of military service members and veterans with mental health conditions. The course is designed specifically to help these individuals understand mental health disorders and improve their ability to support their service member or veteran.

Visit the Veterans Affairs (VA) website for additional information on health care and other benefits for military service members.

Visit the NAMI Homefront course to learn more about mental health conditions and resources available to military service members and their families.

Racial and Ethnic Minorities

Racial and ethnic minority populations in the United States experience significant health disparities.[14] See Figure 17.3[15] for an image of a child from a minority population. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health provides Minority Population Profiles for Black/African Americans, American Indian/Alaska Natives, Asian Americans, Hispanic/Latinos, and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders. Profiles include demographics, English language fluency, education, economics, insurance coverage and health status information, and full census reports. Nurses can access these profiles to view health care statistics regarding these populations and services available in their communities.

The Office of Minority Health is dedicated to improving the health of racial and ethnic minority populations through the development of health policies and programs that help eliminate health disparities.

Visit the Office of Minority Health to learn more about efforts to improve the health of racial and ethnic minority populations through health policy and program development. Examples of initiatives include the following[16]:

COVID-19 Response

Improving Cultural Competency for Behavioral Health Professionals

Sickle Cell Disease Initiative

LGBTQ Population

The lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer or questioning (LGBTQ) population encompasses all races and ethnicities, religions, and social classes. See Figure 17.4[17] for an image of a pride festival by an LGBTQ population. Research suggests that LGBTQ individuals experience health disparities linked to societal stigma, discrimination, and denial of their civil rights.[18] The LGBTQ population experiences high rates of mental health disorders, substance abuse, and suicide, and experiences of violence and victimization are frequent for LGBTQ individuals and can result in long-lasting effects.[19]

Community efforts to improve the health of the LGBTQ population include these initiatives[20]:

- Training health professionals to appropriately inquire and support clients’ sexual orientation and gender identity to promote regular use of health care services

- Training health professionals and students regarding culturally competent care

- Providing supportive social services to reduce suicide and homelessness among youth

- Curbing sexually transmitted infections and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmission

Discover health services by state at CDC’s LGBT Health website.

Human Trafficking Victims

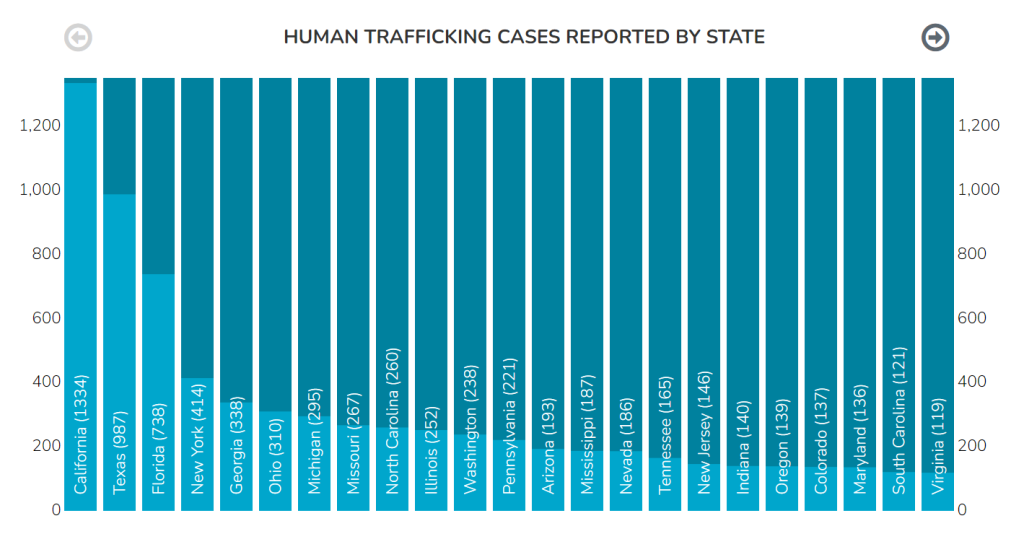

Human trafficking victims are forced to work or provide commercial sex against their will in legal business settings and underground markets.[21] The International Labor Organization estimates there are 40.3 million victims of human trafficking globally. Victims include men, women, adolescents, and children.[22] Experts estimate that 100,000 incidents of sexual exploitation of minors occur each year in the United States.[23] Human trafficking victims have been identified in cities, suburbs, and rural areas in all 50 states and in Washington, D.C. See Figure 17.5[24] regarding human trafficking statistics reported by state in 2020.

Widespread lack of awareness and understanding of trafficking leads to low levels of victim identification. Individuals at risk include runaway and homeless youth, foreign nationals, and individuals with prior history of experiencing violence or abuse. A study in Chicago found that 56 percent of female prostitutes were initially runaway youth, and similar numbers have been identified for male populations.[25]

Foreign nationals who are trafficked within the United States face unique challenges. Recruiters located in home countries frequently require such large recruitment and travel fees that victims become highly indebted to the recruiters and traffickers.

Individuals who have experienced violence and trauma in the past are more vulnerable to future exploitation because the psychological effect of trauma is often long-lasting and challenging to overcome. Victims of domestic violence, sexual assault, war, or social discrimination may be targeted by traffickers who recognize the vulnerabilities left by these prior abuses.[26]

These are some of the services victims of trafficking may need[27]:

- Emergency Services

- Crisis Intervention and Counseling

- Emergency Shelter and Referrals

- Urgent Medical Care

- Safety Planning

- Food and Clothing

For more information about the services available to victims of human trafficking, visit the National Human Trafficking Hotline Referral Directory.

See an example of a nurse providing care for victims of human trafficking in their community in the “Spotlight Application” section.

Incarcerated Individuals and Their Families

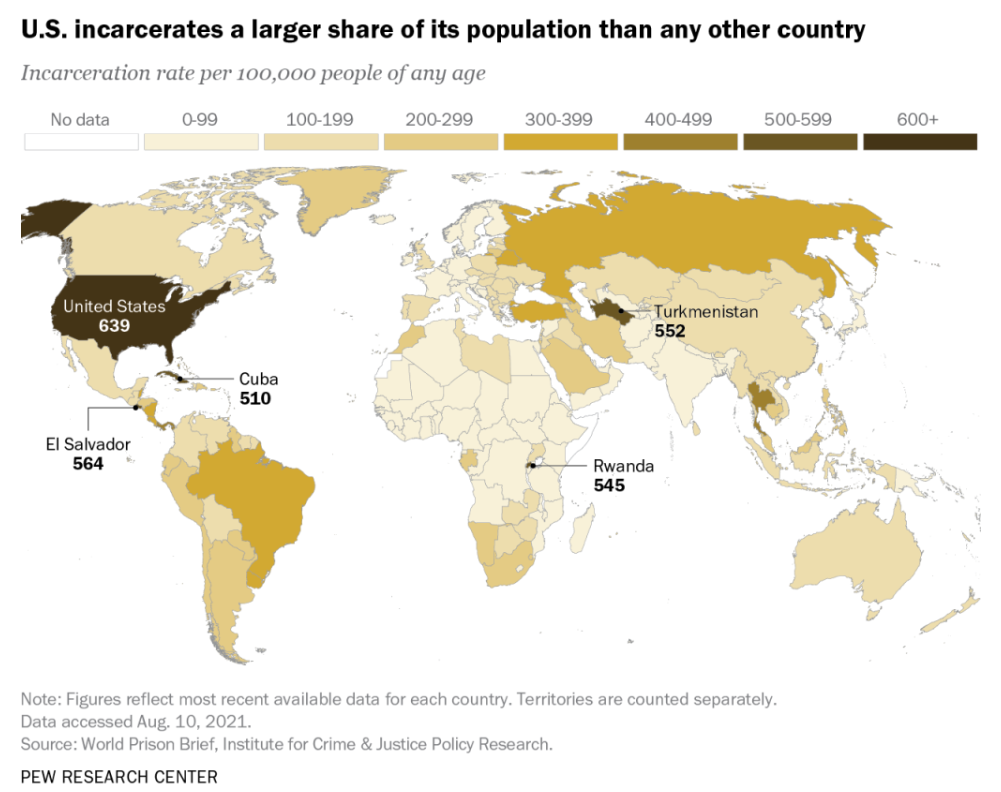

At the end of 2019, there were over 2 million people in U.S. prisons and jails with a nationwide incarceration rate of 810 inmates for every 100,000 adults. Higher rates of incarceration are seen among racial/ethnic minorities and people with lower levels of education. The United States incarcerates a larger share of its population than any other country in the world.[28] See Figure 17.6[29] for an illustration comparing worldwide incarceration rates.[30]

Many individuals who are incarcerated have chronic health conditions, including mental illness and addiction. Over half of all inmates have a mental health disorder, and female inmates have higher rates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) than the general population. In fact, some experts believe that escalation of U.S. incarceration rates since the 1970s is associated with inadequate community-based health care for mental illness and addiction; left untreated, both conditions can lead to behaviors that result in incarceration.[31]

Health care is a constitutional right for prisoners. The 1976 Supreme Court decision in Estelle v. Gamble found that “deliberate indifference to serious medical needs of prisoners” constitutes a violation of the Eighth Amendment prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment. Nurses working in correctional facilities have a legal and ethical obligation to respond to requests for care. If an inmate’s safety complaints are ignored, safety risks are not removed, or there is failure to provide proper medical attention, it is considered "deliberate indifference." Correctional nurses have a duty to evaluate prisoners’ health needs and determine the level of care required. For example, the nurse determines if the prisoner should be moved to the medical unit or transferred to a health facility that can provide the level of care needed. In addition, all pertinent information of health encounters with prisoners must be thoroughly documented and include assessment finding, health needs, interventions taken, patient education, and evaluation of patient outcomes.[32]

While the Supreme Court decision mandates health care provision for incarcerated populations in prisons and jails, it does not extend to those under supervision within the criminal justice system (e.g., on parole, probation, or home confinement).[33] However, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) helps to ensure continuity of medical coverage and care when prisoners are released into the community.[34]

While mortality rates within prisons and jails are comparable to those of the general population, releasees are nearly 13 times more likely to die in the two weeks following their release than the general population. The most common cause of death is overdose. Interventions that follow in-prison drug treatment programs with post-release treatment have been shown to reduce drug use and associated recidivism (i.e., return to prison). There have also been efforts to improve the outcomes of prisoner reentry to society through assistance with employment, housing, and other transitional needs that ultimately affect health.[35],[36]

The National Alliance on Mental Health (NAMI) provides several Re-Entry Planning resources.

Incarceration has a public health impact on prisoners’ family members and their communities while they are incarcerated, as well as after their release. Community health is affected by incarceration due to economic impacts (i.e., consequences on families’ well-being when income earners are removed) and long-term impacts on children’s health and mental health (also referred to as adverse childhood events). For example, children of incarcerated parents are more likely to live in poverty, as well as have higher rates of learning disabilities, developmental delays, speech/language problems, attention disorders, aggressive behaviors, and drug and alcohol use. Additionally, children of incarcerated parents are up to five times more likely to enter the criminal justice system than children of nonincarcerated parents.[37],[38]

Family-centered services for incarcerated parents and their children focus on parenting programs, family strengthening activities, nurturing of family relationships, and community support for families during incarceration and following release.

Read more about family-centered services at U.S. Department of Health Services Child Welfare Information Gateway.

Read additional guidance and resources at CDC Correctional Health.

Rural Americans

Rural Americans are a population group that experiences significant health disparities. Rural risk factors for health disparities include geographic isolation, lower socioeconomic status, higher rates of health risk behaviors, limited access to health care specialists, and limited job opportunities. This inequality is intensified because rural residents are less likely to have employer-provided health insurance or Medicaid coverage.[39],[40] See Figure 17.7[41] for an image of a small town in rural America.

For an in-depth look at rural health disparities, the Rural Health Information Hub Rural Health Series serves as a resource to examine rural mortality and preventable deaths, health-related behaviors, chronic disease, mental health services, and other related topics. The Federal Office of Rural Health Policy provides additional information regarding rural health policy, community health programs, and telehealth programs to increase access to health care for underserved people in rural communities.

Visit the Rural Health Information Hub Rural Health Series to examine rural mortality and preventable deaths, health-related behaviors, chronic disease, mental health services, and other related topics.

Learn more about the NHSC and how it supports health care professionals to provide care in areas with limited access to health services.

Migrant Workers

A migrant worker is a person who moves within their home country or outside of it to pursue work. Migrant workers usually do not intend to stay permanently in the country or region in which they work. See Figure 17.10[42] for an image of migrant workers harvesting cabbage.

Migratory and seasonal agricultural workers (MASW) and their families face unique health challenges that can result in significant health disparities. Challenges can include the following[43]:

- Hazardous work environments

- Poverty

- Insufficient support systems

- Inadequate or unsafe housing

- Limited availability of clean water and septic systems

- Inadequate health care access and lack of continuity of care

- Lack of health insurance

- Cultural and language barriers

- Fear of using health care due to immigration status

- Lack of transportation

MSAW populations experience serious health problems including diabetes, malnutrition, depression, substance use, infectious diseases, pesticide poisoning, and injuries from work-related machinery. These critical health issues are exacerbated by the migratory culture of this population group that increases isolation and makes it difficult to maintain treatment regimens and track health records.[44]

Successful strategies to support health services for migrant workers are as follows[45]:

- Culturally sensitive health education and outreach

- Educational materials at the appropriate literacy level

- Portable medical records and case management

- Mobile medical units

- Transportation services

- Translation services

Nurses can refer uninsured migrant farmworkers to Migrant Health Centers or other federally qualified health centers that are open to everyone. Individuals who do not have health insurance can pay for services based on a sliding-fee scale.

Read more about promoting migrant worker health at the Rural Migrant Health Information Hub.

Individuals with Mental Health Disorders

One in five American adults experiences some form of mental illness. Despite a recent focus on mental health in America, there are still many harmful attitudes and misunderstandings surrounding mental illness that can cause people to ignore their mental health and make it harder to reach out for help.[46]

Many individuals with mental health disorders go undiagnosed. Nurses must be aware of these common signs of mental health disorders[47]:

- Excessive worrying or fear

- Excessively sad feelings

- Confused thinking or problems concentrating and learning

- Extreme mood changes, including uncontrollable “highs” or feelings of euphoria

- Prolonged or strong feelings of irritability or anger

- Avoidance of friends and social activities

- Difficulties understanding or relating to other people

- Changes in sleeping habits or feeling tired and low energy

- Changes in eating habits, such as increased hunger or lack of appetite

- Changes in sex drive

- Disturbances in perceiving reality (e.g., delusions and hallucinations)

- Inability to perceive changes in one’s own feelings, behavior, or personality (i.e., lack of insight)

- Overuse of substances like alcohol or drugs

- Multiple physical ailments without obvious causes (such as headaches, stomachaches, or vague and ongoing “aches and pains”)

- Thoughts of suicide

- Inability to carry out daily activities or handle daily problems and stress

- An intense fear of weight gain or overly concerned with appearance

Mental health conditions are also present in children. Because children are still learning how to identify and talk about thoughts and emotions, their most obvious symptoms are behavioral. Behavioral symptoms in children can include the following[48]:

- Changes in school performance

- Excessive worry or anxiety

- Hyperactive behavior

- Frequent nightmares

- Frequent disobedience or aggression

- Frequent temper tantrums

Healthcare workers should recognize signs and symptoms of potentially undiagnosed mental health problems in all care settings and make appropriate referrals to mental health professionals and support organizations.

National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) provides advocacy, education, support, and public awareness so that all individuals and families affected by mental illness can build better lives. NAMI’s strategic goals are for people to get help early, get the best possible care, and be diverted from justice system involvement.[49]

NAMI offers these programs that promote improved care for individuals with mental illness and their loved ones:

- Your Journey With Mental Illness is a web page with several resources such as understanding your diagnosis, finding a health professional, understanding insurance, handling a crisis, and navigating finances and work.

- NAMI Basics is an educational program for parents, family members, and caregivers who provide care for youth (ages 22 and younger) who are experiencing mental health symptoms. The program covers these topics:

- Impact mental health conditions can have on the entire family

- Different types of mental health care professionals and available treatment options and therapies

- Overview of the public mental health care, school, and juvenile justice systems and resources to help navigate these systems

- Child rights advocacy at school and in health care settings

- Preparation and response to crisis situations (self-harm, suicide attempts, etc.)

- Importance of self-care

- NAMI Provider introduces mental health professionals to the unique perspectives of people with mental health conditions and their families. It promotes empathy for their daily challenges and the importance of including them in all aspects of the treatment process.

- NAMI In Our Own Voice is a program to promote a change in attitudes, assumptions, and ideas about people with mental health conditions. Presentations provide a personal perspective of mental health conditions, as leaders with lived experience talk openly about what it's like to have a mental health condition.

Homeless People

Homelessness can significantly affect an individual’s health in three ways: health problems caused by homelessness, health problems that cause homelessness, and health conditions that are difficult to treat because of homelessness. As a result, the average age of death among homeless people is the mid-50s.[50]

Homeless people face multiple barriers to health care, including transportation, fragmentation of health care services, difficulty scheduling and keeping appointments, stigma of homelessness, lack of trust, social isolation, and significant basic physiological needs. Homeless people frequently have multiple needs resulting from exposure to violence or the elements, food insecurity, and untreated or undertreated physical and mental illnesses, resulting in frequent emergency department visits and hospitalizations.[51]

Attribution

This section contains content taken from Nursing: Mental Health and Community Concepts by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.