3.2 Communication

The third IPEC competency focuses on interprofessional communication and states, “Communicate with patients, families, communities, and professionals in health and other fields in a responsive and responsible manner that supports a team approach to the promotion and maintenance of health and the prevention and treatment of disease.”[1] See Figure 3.1[2] for an image of interprofessional communication supporting a team approach. This competency also aligns with The Joint Commission’s National Patient Safety Goal for improving staff communication.[3] See the following box for the components associated with the Interprofessional Communication competency.

Components of IPEC’s Interprofessional Communication Competency[4]

- Choose effective communication tools and techniques, including information systems and communication technologies, to facilitate discussions and interactions that enhance team function.

- Communicate information with patients, families, community members, and health team members in a form that is understandable, avoiding discipline-specific terminology when possible.

- Express one’s knowledge and opinions to team members involved in patient care and population health improvement with confidence, clarity, and respect, working to ensure common understanding of information, treatment, care decisions, and population health programs and policies.

- Listen actively and encourage ideas and opinions of other team members.

- Give timely, sensitive, constructive feedback to others about their performance on the team, responding respectfully as a team member to feedback from others.

- Use respectful language appropriate for a given difficult situation, crucial conversation, or conflict.

- Recognize how one’s uniqueness (experience level, expertise, culture, power, and hierarchy within the health care team) contributes to effective communication, conflict resolution, and positive interprofessional working relationships.

- Communicate the importance of teamwork in patient-centered care and population health programs and policies.

Transmission of information among members of the health care team and facilities is ongoing and critical to quality care. However, information that is delayed, inefficient, or inadequate creates barriers for providing quality of care. Communication barriers continue to exist in health care environments due to interprofessional team members’ lack of experience when interacting with other disciplines. For instance, many novice nurses enter the workforce without experiencing communication with other members of the health care team (e.g., providers, pharmacists, respiratory therapists, social workers, surgical staff, dieticians, physical therapists, etc.). Additionally, health care professionals tend to develop a professional identity based on their educational program with a distinction made between groups. This distinction can cause tension between professional groups due to diverse training and perspectives on providing quality patient care. In addition, a health care organization’s environment may not be conducive to effectively sharing information with multiple staff members across multiple units.

In addition to potential educational, psychological, and organizational barriers to sharing information, there can also be general barriers that impact interprofessional communication and collaboration. See the following box for a list of these general barriers.

General Barriers to Interprofessional Communication and Collaboration[5]

- Personal values and expectations

- Personality differences

- Organizational hierarchy

- Lack of cultural humility

- Generational differences

- Historical interprofessional and intraprofessional rivalries

- Differences in language and medical jargon

- Differences in schedules and professional routines

- Varying levels of preparation, qualifications, and status

- Differences in requirements, regulations, and norms of professional education

- Fears of diluted professional identity

- Differences in accountability and reimbursement models

- Diverse clinical responsibilities

- Increased complexity of patient care

- Emphasis on rapid decision-making

There are several national initiatives that have been developed to overcome barriers to communication among interprofessional team members. These initiatives are summarized in Table 3.1.

| Action | Description |

|---|---|

| Teach structured interprofessional communication strategies | Structured communication strategies, such as ISBARR, handoff reports, I-PASS reports, and closed-loop communication should be taught to all health professionals. |

| Train interprofessional teams together | Teams that work together should train together. |

| Train teams using simulation | Simulation creates a safe environment to practice communication strategies and increase interdisciplinary understanding. |

| Define cohesive interprofessional teams | Interprofessional health care teams should be defined within organizations as a cohesive whole with common goals and not just a collection of disciplines. |

| Create democratic teams | All members of the health care team should feel valued. Creating democratic teams (instead of establishing hierarchies) encourages open team communication. |

| Support teamwork with protocols and procedures | Protocols and procedures encouraging information sharing across the whole team include checklists, briefings, huddles, and debriefing. Technology and informatics should also be used to promote information sharing among team members. |

| Develop an organizational culture supporting health care teams | Agency leaders must establish a safety culture and emphasize the importance of effective interprofessional collaboration for achieving good patient outcomes. |

Communication Strategies

Several communication strategies have been implemented nationally to ensure information is exchanged among health care team members in a structured, concise, and accurate manner to promote safe patient care. Examples of these initiatives are ISBARR, handoff reports, closed-loop communication, and I-PASS. Documentation that promotes sharing information interprofessionally to promote continuity of care is also essential. These strategies are discussed in the following subsections.

Closed-Loop Communication

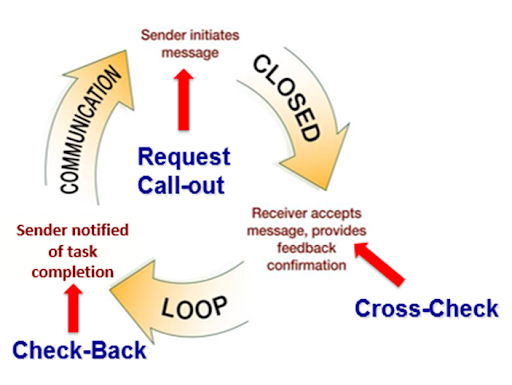

The closed-loop communication strategy is used to ensure that information conveyed by the sender is heard by the receiver and completed. Closed-loop communication is especially important during emergency situations when verbal orders are being provided as treatments are immediately implemented. See Figure 3.2[7] for an illustration of closed-loop communication.

- The sender initiates the message.

- The receiver accepts the message and repeats back the message to confirm it (i.e., “Cross-Check”).

- The sender confirms the message.

- The receiver notified the sender the task was completed (i.e., “Check-Back”).

See an example of closed-loop communication during an emergent situation in the following box.

Closed-Loop Communication Example

Doctor: “Administer 25 mg Benadryl IV push STAT.”

Nurse: “Give 25 mg Benadryl IV push STAT?”

Doctor: “That’s correct.”

Nurse: “Benadryl 25 mg IV push given at 1125.”

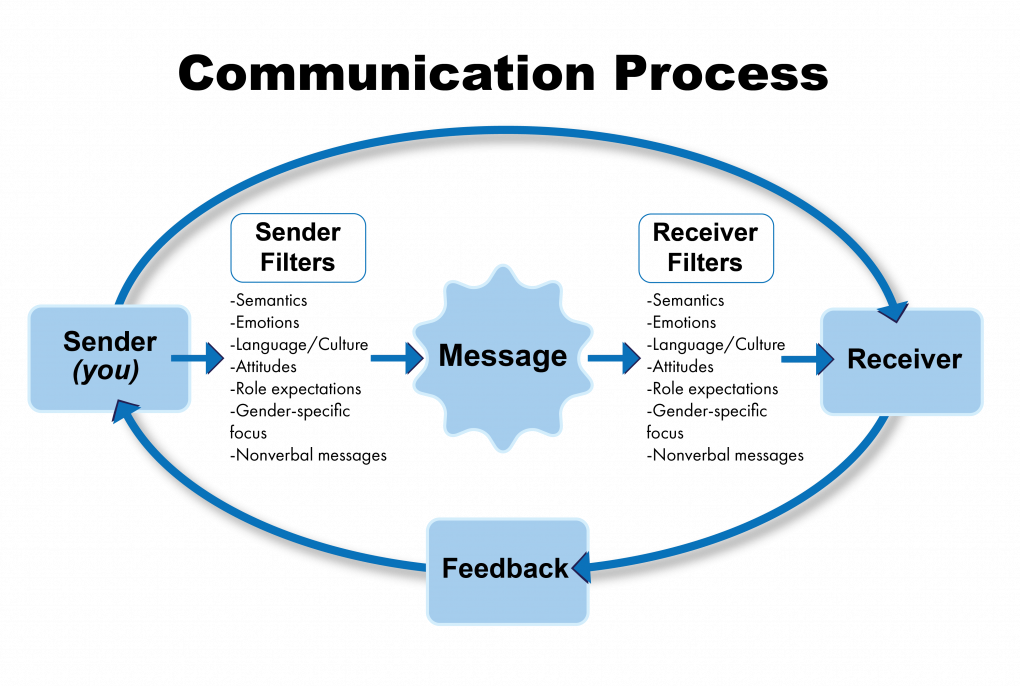

Communication is a process by which information is exchanged between individuals through a common system of symbols, signs, or behavior.[8] In the health care setting, good communication is the foundation to trusting relationships that improve client outcomes. It is the gateway to providing holistic care. Holistic care addresses a client’s physical, emotional, social, and spiritual needs.[9] The communication process involves a sender, the message, and a receiver. See Figure 3.3[10] for an illustration of the communication process.

Verbal Messages

There are many aspects of the communication process that can alter the delivery and interpretation of the message. These aspects relate to the language and experience of both the sender and receiver, referred to as semantics. People typically make reference to things they are familiar with, including landmarks, popular culture, and slang. Barriers can occur even when both parties in the conversation speak the same language. For example, if you asked a person who has never used the Internet to “Google it,” they would have no idea what that means.

Nonverbal Messages

Nonverbal messages, also referred to as body language, greatly impact the conversational process. Nonverbal communication includes body language and facial expressions, tone of voice, and pace of the conversation. See Figure 1.2[11] for an illustration of body language communicating a message. Nonverbal communication can have a tremendous impact on the communication experience and may be much more powerful than the verbal message itself. You may have previously learned that 80% of communication is nonverbal communication. The importance of nonverbal communication during conversation has been broken down further, estimating that 55% of communication is body language, 38% is tone of voice, and 7% is the actual words spoken.[12] If the sender or receiver appears disinterested or distracted, the message or interpretation may become distorted or missed.

Health care professionals assess receivers’ preferred methods of communication and individual characteristics that might influence communication and then adapt communication to meet the receivers’ needs. For example, nursing assistants adapt verbal instructions for adult patients with cognitive disabilities. Although the information provided might be similar to that provided to a patient without disabilities, the way the information is provided is adapted based on the patient’s developmental level. A nursing assistant may ask a cognitively intact person, “What do you want for lunch?” but adapt this information for someone with impaired cognitive function by offering a choice, such as “Do you want a sandwich or soup for lunch?” This adaptation allows the cognitively impaired patient to make a choice without being confused or overwhelmed by too many options.[13] Read more about developmental levels in the “Human Needs and Developmental Stages” section of this chapter.

Communication Styles

In addition to using verbal and nonverbal communication, people communicate with others using one of three styles. A passive communicator puts the rights of others before their own. Passive communicators tend to be apologetic or sound tentative when they speak and often do not speak up if they feel as if they are being wronged. Aggressive communicators[ on the other hand, come across as advocating for their own rights despite possibly violating the rights of others when communicating. They tend to communicate in a way that tells others their feelings don’t matter. Assertive communicators respect the rights of others while also standing up for their own ideas and rights when communicating. An assertive person is direct, but not insulting or offensive.[14]

Assertive communication refers to a way of conveying information that describes the facts and the sender’s feelings without disrespecting the receiver’s feelings. Assertive communication is different from aggressive communication because it uses “I” messages, such as “I feel…,” “I understand…,” or “Help me to understand…,” to address issues instead of using “you” messages that can cause the receiver to feel as though they are being verbally attacked. Using assertive communication is an effective way to solve problems with patients, coworkers, and health care team members. For example, instead of using aggressive communication to say to a coworker, “You always leave your patients’ rooms a mess! I dread following you on the next shift,” an assertive communicator would use “I” messages. The assertive communicator might say, “I feel frustrated spending the first part of my shift decluttering patients’ rooms. Help me understand the reasons why you don’t empty the wastebaskets and clean up the rooms by the end of your shift.”[15]

Overcoming Communication Barriers

It is important to reflect on personal factors that influence your ability to communicate with others effectively. There are many factors that can distort the message you are trying to communicate, resulting in your message not being perceived by the receiver in the way you intended. When communicating, it is important to seek feedback that your message is clearly understood.[16]

Common Barriers to Communication in Health Care[17]

- Jargon: Avoid using medical terminology, complicated wording, or unfamiliar words. When communicating with patients, explain information in common language that is easy to understand. Consider any generational, geographical, or background information that may change the perception or understanding of your message.

- Lack of attention: It is easy to become task-centered rather than person-centered when caring for multiple residents. When entering a patient’s room, remember to use preprocedural steps and mindfully focus on the person in front of you to give them your full attention. Patients should feel as if they are the center of your attention when you are with them, no matter how many other things you have going on.

- Noise and other distractions: Health care environments can be very noisy with people talking in the room or hallway, the TV blaring, alarms beeping, and pages occurring overhead. Create a calm, quiet environment when communicating with patients by closing doors to the hallway, reducing the volume of the TV, or moving to a quieter area, if possible.

- Light: A room that is too dark or too light can create communication barriers. Ensure the lighting is appropriate according to the patient’s preference.

- Hearing and speech problems: If your patient has hearing or speech problems, implement strategies to enhance communication, including assistive devices such as eyeglasses, hearing aids, and any communication aids such as whiteboards, photobooks, or microphones.

- Language differences: If English is not your patient’s primary language, it is important to seek a medical interpreter and provide written handouts in the patient’s preferred language when possible. Most agencies have access to an interpreter service available by phone if they are not available on-site.

- Differences in cultural beliefs: The norms of social interaction vary greatly in different cultures, as well as the ways that emotions are expressed. For example, the concept of personal space varies among people from different cultural backgrounds. Some people prefer to stand very close to one another when speaking whereas others prefer a distance of a few feet. Additionally, some patients are stoic about pain whereas others are more verbally expressive when in pain.

- Psychological barriers: Psychological states of the sender and the receiver affect how the message is sent, received, and perceived. Consider what the receiver may be experiencing in the health care setting and what may change your delivery of your message. Being rushed, distracted, and overwhelmed are just a few things that can affect your message and its understanding.

- Physiological barriers: It is important to be aware of patients’ potential physiological barriers when communicating. For example, if a patient is in pain, they are less likely to hear and remember what was said. If the patient is receiving pain medication, be aware these medications may alter their comprehension and response.

- Physical barriers for nonverbal communication: Providing information via email or text is often less effective than face-to-face communication. The inability to view the nonverbal communication associated with a message, such as tone of voice, facial expressions, and general body language, often causes misinterpretation of the message by the receiver. When possible, it is best to deliver important information to others using face-to-face communication so that nonverbal communication is included with the message.

- Differences in perceptions and viewpoints: Everyone has their own beliefs and perspectives and wants to feel “heard.” When patients feel their beliefs or perspectives are not valued, they often become disengaged from the conversation or their plan of care. Information should be provided in a nonjudgmental manner, even if the patient’s perspectives, viewpoints, and beliefs are different from your own.

Communicating With the Client, Families, and Loved Ones

Therapeutic communication is a type of professional communication used with patients. It is defined as the purposeful, interpersonal, information-transmitting process through words and behaviors based on both parties’ knowledge, attitudes, and skills that leads to patient understanding and participation.[18] Therapeutic communication techniques have been used by nurses since Florence Nightingale, who insisted on the importance of building trusting relationships with patients. She believed in the therapeutic healing that results from nurses’ presence with patients.[19]

There are several components included in therapeutic communication. The health care professional uses active listening and attending behaviors to demonstrate they are interested in understanding what the patient is saying. Touch is used to professionally communicate caring, and specific therapeutic techniques are used to encourage the patient to share their thoughts, concerns, and feelings.

Active Listening and Attending Behaviors

Listening is obviously an important part of communication. A well-known phrase from a Greek philosopher named Epictetus is, “We have two ears and one mouth so we can listen twice as much as we speak.” It is important to actively listen to patients and not use competitive or passive listening. Competitive listening occurs when we are primarily focused on sharing our own point of view instead of listening to someone else. Passive listening occurs when we are not interested in listening to the other person or we assume we correctly understand what the person is communicating without verifying their message. During active listening, we communicate verbally and nonverbally that we are interested in what the other person is saying and also verify our understanding with the speaker. For example, an active listening technique is to restate what the person said and verify our understanding is correct, such as, “I hear you saying you are hesitant to go to physical therapy because you are afraid of falling. Is that correct?” This feedback process is the main difference between passive listening and active listening.[20]

Touch

Touch is a powerful way to professionally communicate caring and compassion if done respectfully while being aware of the patient’s cultural beliefs. For example, simply holding a patient’s hand during a painful procedure can be very effective in providing comfort. See Figure 1.4[21] for an image of a nurse using touch as a therapeutic technique when caring for a patient.

Therapeutic Communication Techniques

Therapeutic communication techniques are specific methods used to provide patients with support and information while focusing on their concerns. It is important to recognize the autonomy of the patient to make their own decisions, maintain a nonjudgmental attitude, and avoid interrupting. Depending on the developmental stage and educational needs of the patient, appropriate terminology should be used to promote patient understanding and rapport. When using therapeutic communication, health care professionals often ask open-ended questions, repeat information, or use silence to prompt patients to process their concerns. Table 1.3a describes a variety of therapeutic communication techniques.

| Therapeutic Technique | Description |

|---|---|

| Active Listening | By using nonverbal and verbal cues such as nodding and saying, “I see,” health care professionals can encourage patients to continue talking. Active listening involves showing interest in what patients have to say, acknowledging that you’re listening and understanding, and engaging with them throughout the conversation. General leads such as “What happened next?” can be used to guide the conversation or propel it forward. |

| Using Silence | At times, it’s useful to not speak at all. Deliberate silence can give patients an opportunity to think through and process what comes next in the conversation. It may also give them the time and space they need to broach a new topic. |

| Providing Acceptance | Sometimes it is important to acknowledge a patient’s message and affirm they’ve been heard. Acceptance isn’t necessarily the same thing as agreement; it can be enough to simply make eye contact and say, “I hear what you are saying.” Patients who feel their health care professionals are listening to them and taking them seriously are more likely to be receptive to care. |

| Giving Recognition | Recognition acknowledges a patient’s behavior and highlights it. For example, saying something such as “I noticed you ate all of your breakfast today” draws attention to the action and encourages it. |

| Offering Self | Hospital stays can be lonely and stressful at times. When health care professionals make time to be present with their patients, it communicates they value them and are willing to give them time and attention. Offering to simply sit with patients for a few minutes is a powerful way to create a caring connection. |

| Giving Broad Openings/Open-Ended Questions | Therapeutic communication is often most effective when patients direct the flow of conversation and decide what to talk about. For example, giving patients a broad opening such as “What’s on your mind today?” or “What would you like to talk about?” is a good way to allow patients an opportunity to discuss what’s on their mind. |

| Seeking Clarification | Similar to active listening, asking patients for clarification when they say something confusing or ambiguous is important. Saying something such as “I’m not sure I understand. Can you explain more to me?” helps health care professionals ensure they understand what’s actually being said and can help patients process their ideas more thoroughly. |

| Placing the Event in Time or Sequence | Asking questions about when certain events occurred in relation to other events can help patients (and health care professionals) get a clearer sense of the whole picture. It forces patients to think about the sequence of events and may prompt them to remember something they otherwise wouldn’t. |

| Making Observations | Making observations about the appearance, demeanor, or behavior of patients can help draw attention to areas that may indicate a problem. For example, making an observation that they haven’t been eating much may lead to the discovery of a new symptom. |

| Encouraging Descriptions of Perception | For patients experiencing sensory issues or hallucinations, it can be helpful to ask about these perceptions in an encouraging, nonjudgmental way. Phrases such as “What do you hear now?” or “What do you see?” give patients a prompt to explain what they’re perceiving without casting their perceptions in a negative light. |

| Encouraging Comparisons | Patients often draw upon previous experiences to deal with current problems. By encouraging them to make comparisons to situations they have coped with before, health care professionals can help patients discover solutions to their problems. |

| Summarizing | It is often useful to summarize what patients have said. This demonstrates you are listening and allows you to verify information. Ending a summary with a phrase such as “Does that sound correct?” gives patients explicit permission to make corrections if they’re necessary. |

| Reflecting | Patients often ask health care professionals for advice about what they should do about particular problems. Instead of offering advice, health care professionals can ask patients to reflect on what they think they should do, which encourages them to be accountable for their own actions and helps them come up with solutions themselves. |

| Focusing | Sometimes during a conversation, patients mention something particularly important. When this happens, health care professionals can focus on this statement and prompt patients to discuss it further. Patients don’t always have an objective perspective on what is relevant to their case, but as impartial observers, health care professionals may be able to pick out the topics on which to focus. |

| Confronting | Health care professionals should only use this technique after they have established trust and rapport with the client. In some situations, it can be vital to disagree with patients, present them with reality, or challenge their assumptions. Confrontation, when used correctly, can help patients break destructive routines or understand the state of their current situation. |

| Voicing Doubt | Voicing doubt can be a gentler way to call attention to incorrect or delusional ideas and perceptions of patients when appropriate. For example, when appropriate, a health care worker may say to a patient experiencing visual hallucinations, “I know you said you are seeing spiders on the walls, but I don’t see any spiders.” |

| Offering Hope and Humor | Because hospitals can be stressful places for patients, sharing hope that they can persevere through their current situation or lightening the mood with humor can quickly establish rapport. This technique can help move patients in a more positive state of mind. However, it is important to tailor humor to the patient’s sense of humor. |

In addition to the therapeutic techniques listed in Table 3.2, health care professionals should genuinely communicate with patients with empathy. Communicating honestly, genuinely, and authentically is powerful. It opens the door to establishing true connections with others.[23] Communicating with empathy can be described as providing “unconditional positive regard.” Research has demonstrated that when health care professionals communicate with empathy, there is improved patient healing, reduced symptoms of depression, and decreased medical errors.[24]

Nontherapeutic Responses

Health care professionals must be aware of potential barriers to communication. In addition to the common communication barriers discussed in the “Communication Styles” subsection of this chapter, there are several nontherapeutic responses to avoid. These nontherapeutic responses often block the patient’s communication of their feelings or ideas. See the table below for a description of nontherapeutic responses.[25]

| Nontherapeutic Response | Description |

|---|---|

| Asking Personal Questions | Asking personal questions that are not relevant to the situation is not professional or appropriate. Don’t ask questions just to satisfy your curiosity. For example, asking, “Why have you and Mary never married?” is not appropriate. A more therapeutic question would be, “How would you describe your relationship with Mary?” |

| Giving Personal Opinions | Giving personal opinions takes away the decision-making from the patient. Effective problem-solving must be accomplished by the patient and not the NA. For example, stating, “If I were you, I’d put your father in a nursing home” is not therapeutic. Instead, it is more therapeutic to say, “Let’s talk about what options are available to your father.” |

| Changing the Subject | Changing the subject when someone is trying to communicate with you demonstrates lack of empathy and blocks further communication. It seems to say that you don’t care about what they are sharing. For example, stating, “Let’s not talk about your insurance problems; it’s time for your walk now” is not therapeutic. A more therapeutic response would be, “After your walk, let’s talk more about your concerns about insurance so I can help find assistance for you.” |

| Stating Generalizations and Stereotypes | Generalizations and stereotypes can threaten relationships with patients. For example, it is not therapeutic to state a stereotype like, “Older adults are always confused.” It is better to focus on the patient’s concern and ask, “Tell me more about your concerns about your wife’s confusion.” |

| Providing False Reassurances | When a patient is seriously ill or distressed, it is tempting to offer false hope with statements such as “You’ll be fine,” or “Don’t worry; everything will be alright.” These comments tend to discourage further expressions of feelings by the patient. A more therapeutic response would be, “It must be difficult not to know what the surgeon will find. What can I do to help?” |

| Showing Sympathy | Sympathy focuses on the health care professional’s feelings rather than the patient. Saying “I’m so sorry about your amputation; I can’t imagine losing a leg” shows pity rather than trying to help the patient cope with the situation. A more therapeutic response would be, “The loss of your leg is a major change; how do you think this will affect your life?” |

| Asking “Why” Questions | It can be tempting to ask a patient to explain “why” they believe, feel, or act in a certain way. However, patients and family members can interpret “why” questions as accusations and become defensive. It is best to phrase a question by avoiding the word “why.” For example, instead of asking, “Why are you so upset?” it is better to rephrase the statement as, “You seem upset. What’s on your mind?” |

| Approving or Disapproving | Health care professionals should not impose their own attitudes, values, beliefs, and moral standards on patients or family members. Judgmental messages contain terms such as “should,” “shouldn’t,” “ought to,” “good,” “bad,” “right,” or “wrong.” Agreeing or disagreeing sends the subtle message that health care professionals have the right to make value judgments about the patient’s decisions. Approving implies that the behavior being praised is the only acceptable one, and disapproving implies that the patient must meet the listener’s expectations or standards. Instead, health care professionals should help the patient explore their own beliefs and decisions. For example, it is nontherapeutic to state, “You shouldn’t schedule elective surgery; there are too many risks involved.” A more therapeutic response would be, “So you are considering elective surgery. Tell me more about it…” This response gives the patient a chance to express their ideas or feelings without fear of being judged. |

| Giving Defensive Responses | When patients or family members express criticism, health care professionals should actively listen. Listening does not imply agreement. To discover reasons for the patient’s anger or dissatisfaction, health care professionals should listen without criticism, avoid being defensive or accusatory, and attempt to defuse anger. For example, it is not therapeutic to state, “No one here would intentionally lie to you.” Instead, a more therapeutic response would be, “You believe people have been dishonest with you. Tell me more about what happened.” (After obtaining additional information, the health care worker may decide to follow the chain of command at the agency and report the patient’s concerns to the nurse supervisor for follow-up.) |

| Providing Passive or Aggressive Responses | Passive responses serve to avoid conflict or sidestep issues, whereas aggressive responses provoke confrontation. Health care workers should use assertive communication. |

| Arguing | Challenging or arguing against patient perceptions denies that they are real and valid to the other person. They imply that the other person is lying, misinformed, or uneducated. The skillful health care professional can provide alternative information or present reality in a way that avoids argument. For example, it is not therapeutic to state, “How can you say you didn’t sleep a wink when I heard you snoring all night long!” A more therapeutic response would be, “You don’t feel rested this morning? Let’s talk about ways to improve your sleep so you feel more rested.” |

Strategies for Effective Communication

In addition to overcoming common communication barriers, using active listening and therapeutic communication techniques, and avoiding nontherapeutic responses, there are additional strategies for promoting effective communication when providing patient-centered care. Specific questions to ask patients are as follows[27]:

- What concerns do you have about your plan of care?

- What questions do you have about your daily routine?

- Did I answer your question(s) clearly, or is there additional information you would like?

Listen closely for feedback from patients. Feedback provides an opportunity to improve patient understanding, improve the patient-care experience, and provide high-quality care. Other suggestions for effective communication with clients include the following:

- Read the care plan carefully and access any social history available. If family members or friends visit and it seems appropriate, talk with them about the client without intruding or taking up a lot of their time together. This information helps you build trust and care for the client based on their preferences and life history. For example, you might learn the resident lived on a farm most of their life and enjoyed taking care of their horses. Striking up conversations about horses is a way to build rapport with this client.

- Review any changes in routine or in the plan of care

- If there are questions you can’t answer, be sure to report to the nurse so someone can follow up with the client. Check back with the client to ensure they have had their questions answered.

- Observe nonverbal communication from clients. Do they seem to interact during care, or is it something that they are merely tolerating and just trying to get through each day? Find an approach so they are comfortable with receiving care.

Adapting Your Communication

When communicating with patients, their family members, and other caregivers, note your audience and adapt your message based on characteristics such as age, developmental level, cognitive abilities, and any communication disorders. For patients with language differences, it is vital to provide trained medical interpreters when important information is communicated.

Adapting communication according to an individual’s age and developmental level includes the following strategies[28]:

- When communicating with children, speak calmly and gently. It is often helpful to demonstrate what will be done during a procedure on a doll or stuffed animal. To establish trust, try using play or drawing pictures.

- When communicating with adolescents, give freedom to make choices within established limits.

- When communicating with older adults, be aware of potential vision and hearing impairments that commonly occur and address these barriers accordingly. For example, if a patient has glasses and/or hearing aids, be sure these devices are in place before communicating.

Strategies for Communicating With Patients With Impaired Hearing, Vision, and Speech

In addition to adapting your communication to your audience, there are additional strategies to use with individuals who have impaired hearing, vision, or speech.

Impaired Hearing

- Gain the person’s attention before speaking (e.g., through touch)

- Minimize background noise

- Position yourself 2-3 feet away from the patient

- Facilitate lip-reading by facing the person directly in a well-lit environment

- Use gestures, when necessary

- Listen attentively, allowing the person adequate time to process communication and respond

- Refrain from shouting at the person

- Ask the person to suggest strategies for improved communication (e.g., speaking toward a better ear, moving to well-lit area, and speaking in a lower-pitched tone)

- Face the person directly, establish eye contact, and avoid turning away mid-sentence

- Simplify language (e.g., do not use slang but do use short, simple sentences), as appropriate

- Read the care plan for information on the preferred method of communicating (whiteboards, pictures, etc.)

- Assist the person using any devices such as hearing aids or voice amplifiers

- Report any changes to the nurse

Impaired Vision

- Identify yourself when entering the person’s space

- Ensure the patient’s eyeglasses are cleaned and stored properly when not in use, and assist the patient in wearing them during waking hours

- Provide adequate room lighting

- Minimize glare (e.g., offer sunglasses, draw window covering, position with face away from window)

- Provide educational materials in large print as available

- Read pertinent information to the patient

- Provide magnifying devices

- Report any changes to the nurse

Impaired Speech[29]

Some patients may have problems processing what they are hearing or in responding to questions due to dementia, brain injuries, or prior strokes. This difficulty is referred to as aphasia. There are different types of aphasia. People with expressive aphasia understand speech and know what they want to say, but frequently speak in short phrases that are produced with great effort. For example, they may intend to say, “I would like to go to the bathroom,” but instead the words, “Bathroom, Go,” are expressed. People with receptive aphasia often speak in long sentences, but what they say may not make sense. They are unable to understand both verbal and written language. Aphasia often causes the person to become frustrated when they cannot communicate their needs. Review the following evidence-based strategies to enhance communication with a person with impaired speech[30]:

- Modify the environment to minimize excess noise and decrease emotional distress

- Phrase questions so the patient can answer using a simple “Yes” or “No,” being aware that patients with expressive aphasia may provide automatic responses that are incorrect

- Monitor the patient for frustration, anger, depression, or other responses to impaired speech capabilities

- Provide alternative methods of speech communication (e.g., writing tablet, flash cards, eye blinking, communication board with pictures and letters, hand signals or gestures, or computer)

- Adjust your communication style to meet the needs of the patient (e.g., stand in front of the patient while speaking, listen attentively, present one idea or thought at a time, speak slowly but avoid shouting, use written communication, or solicit the family’s assistance in understanding the patient’s speech)

- Ensure the call light is within reach

- Repeat what the client said to ensure accuracy

- Instruct the client to speak slowly

- Read the care plan for instructions from the speech therapist

- Report any changes to the nurse

Responding to Challenging Situations

Being a care provider is a very rewarding career, but it also includes dealing with challenging situations. Using strong communication techniques can de-escalate situations and put patients, loved ones, and staff at ease. It is impossible to predict what behavior you may encounter as a health care worker, but having a solid basis of communication techniques can prepare you to better handle unique situations.

Memory Impairment and Behavioral Health Issues

Healthcare workers may encounter older adults with varying degrees of memory impairment. Older adults are defined as adults aged 65 years old or older.[31] Residents with memory issues often become confused and can feel overwhelmed by everyday situations. For those with impaired cognitive functioning like dementia, it may not be possible to reorient them to the current time and place or to move them on from thoughts that are not based in the current situation. Aphasia and confusion can cause frustration that can result in agitation or aggression. Agitation refers to behaviors that fall along a continuum ranging from verbal threats and motor restlessness to harmful aggressive and destructive behaviors. Mild agitation includes symptoms such as irritability, oppositional behavior, inappropriate language, and pacing. Severely agitated patients are at immediate risk of harming themselves or others through assaultive or self-injurious behavior, and they are capable of causing property damage.[32] Aggression is an act of attacking without provocation.[33] See below for general guidelines to prevent aggression and agitation:

- Keep the environment calm and as quiet as possible.

- Build trusting relationships by learning resident preferences and routines.

- Gather information from family members and loved ones about the patient’s background and beliefs.

- Offer choices to allow the patient to communicate preferences, but do not cause them to be overwhelmed with too many decisions.

- Empathize with the resident and understand that challenging behavior is often communication of emotion due to cognitive impairment and not a choice.

- Practice validation therapy. Validation therapy is a method of therapeutic communication used to connect with someone who has moderate- to late-stage dementia and avoid agitation. It places more emphasis on the emotional aspect of a conversation and less on the factual content, thereby imparting respect to the person, their feelings, and their beliefs. Validation may require you to agree with a statement that has been made, even though the statement is neither true or real, because to the person with dementia, it feels both true and real.[34] For example, if the resident with dementia believes they are waiting to catch the bus and is intent on doing so, sit with them by the window as if you are waiting for a bus and continue to have interaction with them until they are no longer concerned with the bus.

- Redirect behavior if appropriate. For example, suggest alternative activities such as walking around the facility, looking at photos, listening to music, or other activities the resident enjoys.

- Focus on safety for residents experiencing delusions or hallucinations. Delusions are unshakable beliefs in something that isn’t true or based on reality. For example, a resident may refuse to eat breakfast because they have a delusion that staff are trying to poison them. Hallucinations are sensing things such as visions, sounds, or smells that seem real but are not. For example, a resident may refuse to enter a room because they have hallucinations of big spiders crawling on the walls. If a patient is having delusions or hallucinations, never contradict them or tell them what they perceive isn’t real. Instead, empathize with them and do whatever is possible to help them feel safe. For example, offer to move to another area or investigate what the resident is concerned about.

Attribution

The content from this chapter was taken from:

Nursing Assistant by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Nursing Management and Professional Concepts by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- Interprofessional Education Collaborative. IPEC core competencies. https://www.ipecollaborative.org/ipec-core-competencies ↵

- "1322557028-huge.jpg" by LightField Studios is used under license from Shutterstock.com ↵

- The Joint Commission. 2021 Hospital national patient safety goals. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/standards/national-patient-safety-goals/2021/simplified-2021-hap-npsg-goals-final-11420.pdf ↵

- Interprofessional Education Collaborative. IPEC core competencies. https://www.ipecollaborative.org/ipec-core-competencies ↵

- O’Daniel, M., & Rosenstein, A. H. (2011). Professional communication and team collaboration. In: Hughes R.G. (Ed.). Patient safety and quality: An evidence-based handbook for nurses. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); Chapter 33. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2637 ↵

- Weller, J., Boyd, M., & Cumin, D. (2014). Teams, tribes and patient safety: Overcoming barriers to effective teamwork in healthcare. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 90(1061), 149-154. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131168 ↵

- Image is derivative of "close-loop.png" by unknown and is licensed under CC0. Access for free at https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/instructor/essentials/pocketguide.html ↵

- Merriam-Webster. Communication. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/communication ↵

- Jasemi, M., Valizadeh, L., Zamanzadeh, V., & Keogh, B. (2017). A concept analysis of holistic care by hybrid model. Indian Journal of Palliative Care, 23(1), 71–80. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-1075.197960 ↵

- “Communication Process” by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Boulder_Worldcup_Vienna_29-05-2010a_semifinals090_Akiyo_Noguchi,_Anna_Stöhr.jpg” by Manfred Werner - Tsui is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Thompson, J. (2011). Is nonverbal communication a numbers game? Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/beyond-words/201109/is-nonverbal-communication-numbers-game ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Human Relations by LibreTexts and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- SkillsYouNeed. (n.d.). Barriers to effective communication. https://www.skillsyouneed.com/ips/barriers-communication.html ↵

- Abdolrahimi, M., Ghiyasvandian, S., Zakerimoghadam, M., & Ebadi, A. (2017). Therapeutic communication in nursing students: A Walker & Avant concept analysis. Electronic Physician, 9(8), 4968–4977. https://doi.org/10.19082/4968 ↵

- Karimi, H., & Masoudi Alavi, N. (2015). Florence Nightingale: The mother of nursing. Nursing and Midwifery Studies, 4(2), e29475. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4557413/ ↵

- This work is a derivative of Human Relations by LibreTexts and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- “Flickr_-_Official_U.S._Navy_Imagery_-_A_nurse_examines_a_newborn_baby..jpg” by Official Navy Page from United States of America MC2 John O'Neill Herrera/U.S. Navy is licensed in the Public Domain ↵

- American Nurse. (n.d.). 17 therapeutic communication techniques. https://www.myamericannurse.com/therapeutic-communication-techniques/ ↵

- Balchan, M. (2016, February 16). The magic of genuine communication. http://michaelbalchan.com/communication/ ↵

- Morrison, E. (2019). Empathetic communication in healthcare. EM Consulting. https://work.cibhs.org/sites/main/files/file-attachments/empathic_communication_in_healthcare_workbook.pdf?1594162691 ↵

- Burke, A. (2021). Therapeutic communication: NCLEX-RN. RegisteredNursing.org. https://www.registerednursing.org/nclex/therapeutic-communication/ ↵

- Burke, A. (2021). Therapeutic communication: NCLEX-RN. RegisteredNursing.org. https://www.registerednursing.org/nclex/therapeutic-communication/ ↵

- Smith, L. L. (2018, June 12). Strategies for effective patient communication. American Nurse. https://www.myamericannurse.com/strategies-for-effective-patient-communication/ ↵

- Butcher, H., Bulechek, G., Dochterman, J., & Wagner, C. (2018). Nursing interventions classification (NIC). Elsevier, pp. 115-116. ↵

- Butcher, H., Bulechek, G., Dochterman, J., & Wagner, C. (2018). Nursing interventions classification (NIC). Elsevier, pp. 115-116. ↵

- Butcher, H., Bulechek, G., Dochterman, J., & Wagner, C. (2018). Nursing interventions classification (NIC). Elsevier, pp. 115-116. ↵

- HealthyPeople.gov. (n.d.). Older adults. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/older-adults ↵

- ScienceDirect. (n.d.). Agitation. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/immunology-and-microbiology/agitation ↵

- Merriam-Webster. Aggression. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/aggression ↵

- Hoyt, J. (Ed.). (2020, January 27). Validation therapy in dementia care. SeniorLiving.org. https://www.seniorliving.org/health/validation-therapy/ ↵

When providing clients with stress management techniques and effective coping strategies, nurses must be aware of common defense mechanisms. Defense mechanisms are reaction patterns used by individuals to protect themselves from anxiety that arises from stress and conflict.[1] Excessive use of defense mechanisms is associated with specific mental health disorders. With the exception of suppression, all other defense mechanisms are unconscious and out of the awareness of the individual. See Table 3.4 for a description of common defense mechanisms.

Table 3.4 Common Defense Mechanisms

| Defense Mechanisms | Definitions | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Conversion | Anxiety caused by repressed impulses and feelings are converted into a physical symptoms.[2] | An individual scheduled to see their therapist to discuss a past sexual assault experiences a severe headache and cancels the appointment. |

| Denial | Unpleasant thoughts, feelings, wishes, or events are ignored or excluded from conscious awareness to protect themselves from overwhelming worry or anxiety.[3],[4] | A client recently diagnosed with cancer states there was an error in diagnosis and they don’t have cancer.

Other examples include denial of a financial problem, an addiction, or a partner’s infidelity. |

| Dissociation | A feeling of being disconnected from a stressful or traumatic event - or feeling that the event is not really happening - to block out mental trauma and protect the mind from too much stress.[5] | A person experiencing physical abuse may feel as if they are floating above their bodies observing the situation. |

| Displacement | Unconscious transfer of one’s emotions or reaction from an original object to a less-threatening target to discharge tension.[6] | An individual who is angry with their partner kicks the family dog. An angry child breaks a toy or yells at a sibling instead of attacking their father. A frustrated employee criticizes their spouse instead of their boss.[7] |

| Introjection | Unconsciously incorporating the attitudes, values, and qualities of another person’s personality.[8] | A client talks and acts like one of the nurses they admire. |

| Projection | A process when one attributes their individual positive or negative characteristics, affects, and impulses to another person or group.[9] | A person conflicted over expressing anger changes “I hate him” to “He hates me.”[10] |

| Rationalization | Logical reasons are given to justify unacceptable behavior to defend against feelings of guilt, maintain self-respect, and protect oneself from criticism.[11] | A client who is overextended on several credit cards rationalizes it is okay to buy more clothes to be in style when spending money that was set aside to pay for the monthly rent and utilities. A student caught cheating on a test rationalizes, “Everybody cheats.” |

| Reaction Formation | Unacceptable or threatening impulses are denied and consciously replaced with an opposite, acceptable impulse.[12] | A client who hates their mother writes in their journal that their mom is a wonderful mother. |

| Regression | A return to a prior, lower state of cognitive, emotional, or behavioral functioning when threatened with overwhelming external problems or internal conflicts.[13] | A child who was toilet trained reverts to wetting their pants after their parents' divorce. |

| Repression | Painful experiences and unacceptable impulses are unconsciously excluded from consciousness as a protection against anxiety.[14] | A victim of incest indicates they have always hated their brother (the molester) but cannot remember why. |

| Splitting | Objects provoking anxiety and ambivalence are viewed as either all good or all bad.[15] | A client tells the nurse they are the most wonderful person in the world, but after the nurse enforces the unit rules with them, the client tells the nurse they are the worst person they have ever met. |

| Suppression | A conscious effort to keep disturbing thoughts and experiences out of mind or to control and inhibit the expression of unacceptable impulses and feelings. Suppression is similar to repression, but it is a conscious process.[16],[17] | An individual has an impulse to tell their boss what they think about them and their unacceptable behavior, but the impulse is suppressed because of the need to keep the job. |

| Sublimation | Unacceptable sexual or aggressive drives are unconsciously channeled into socially acceptable modes of expression that indirectly provide some satisfaction for the original drives and protect individuals from anxiety induced by the original drive.[18] | An individual with an exhibitionistic impulse channels this impulse into creating dance choreography. A person with a voyeuristic urge completes scientific research and observes research subjects. An individual with an aggressive drive joins the football team.[19] |

| Symbolization | The substitution of a symbol for a repressed impulse, affect, or idea.[20] | A client unconsciously wears red clothing due a repressed impulse to physically harm someone. |