5.2 Human Needs and Developmental Stages

It is important to understand human needs and developmental stages to communicate effectively and provide holistic care.

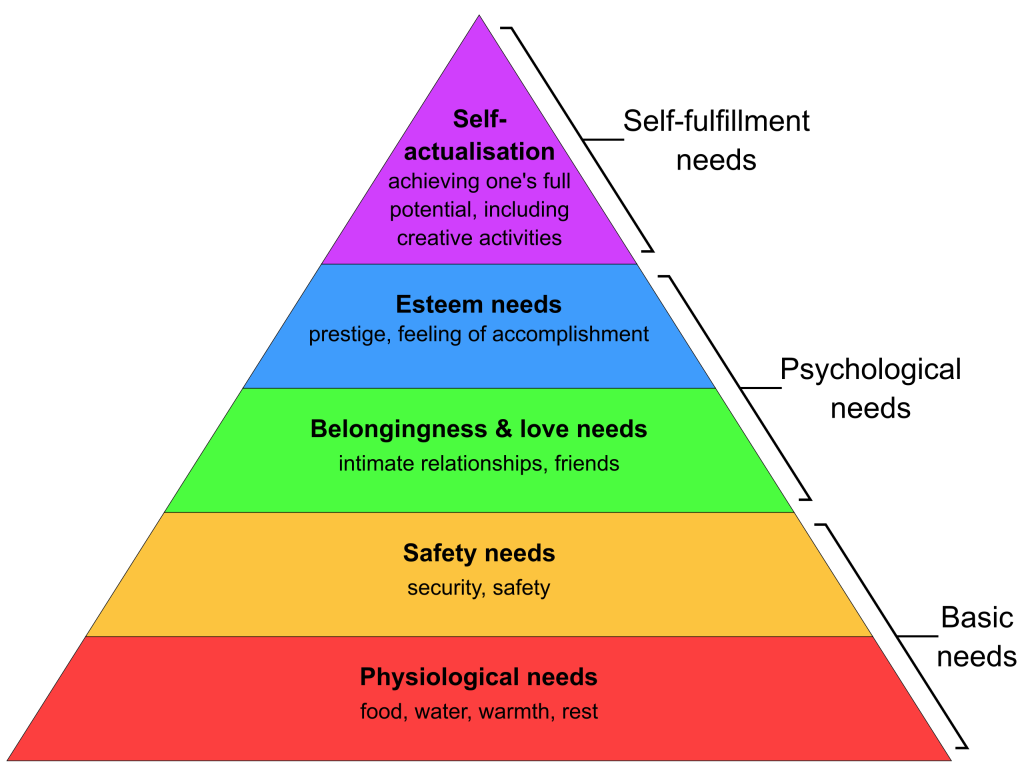

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs was created in 1943 by American psychologist Abraham Maslow. Maslow’s theory is based on the ranking of the importance of human needs and the belief that human actions are based on motivation to meet these needs. See an illustration of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs in Figure 1.5.[1]

Maslow’s theory states that unless the basic needs in the lower levels of the hierarchy are met, humans cannot experience the higher levels of psychological and self-fulfillment needs. The levels of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs have the following definitions[2]:

- Physiological needs: This is the most important level with basic needs humans must have to stay alive and function, including air, food, drink, shelter, clothing, warmth, sex, and sleep.

- Safety needs: People want to experience order, predictability, and control in their lives. This includes emotional security, freedom from fear, and health and well-being (such as safety against falls and injury). For new residents in a long-term care facility, this level includes becoming comfortable in familiar surroundings as opposed to feeling apprehension when experiencing a new environment.

- Love and belongingness: After physiological and safety needs have been fulfilled, the third level of human needs is social and involves feelings of belongingness. Belongingness refers to a human emotional need for interpersonal relationships, connectedness, and being part of a group. A group may mean biological families, friends, or other supporters. It may also include physical intimacy and romantic relationships.

- Esteem needs: Esteem needs include self-worth and feelings of accomplishment and respect. It includes how one views oneself and the feeling of contributing to something of importance.

- Self-actualization: Self-actualization is the highest level and refers to the realization of a person’s potential and self-fulfillment. This level refers to the desire to attain life goals and being truly satisfied in being the most one can be.

Maslow theorized that one cannot attain a higher level in any of these categories if the levels below are not met. For example, one is not motivated by a sense of belonging if they are focused on obtaining basic needs such as food, water, and shelter. The hierarchy is subjective because each individual determines what each level means for them. For instance, for one person, safety may mean living in the neighborhood where they grew up, whereas for another individual it means having a daily routine. Belongingness to one person may mean being a part of a community group whereas to another it may mean having one very close friend. Self-esteem and feelings of accomplishment may be defined by one person as successfully graduating from high school, whereas to another it is defined by being able to run a mile without stopping. Self-actualization is defined by each individual and can mean things such as being a good parent, graduating from college, or achieving one’s dream of becoming a nurse.

The levels of belongingness and self-actualization also include a person’s spirituality and how they find meaning and purpose in life. Spirituality is often mistakenly equated with religion, but spirituality is a broader concept that includes how people seek meaning and purpose in life, as well as establish relationships with family, their community, nature, and/or a higher power.[3]

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs is a good basis for providing holistic care and communicating with clients based on their needs and preferences. For example, in nursing, priorities of care are based on physiological needs and safety. Additionally, knowing that a newly admitted resident may have difficulty reaching a higher level of needs if their basic needs are not met is a good starting point for providing care. Examples of care that integrate Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs include the following:

- Following the care plan to meet physiological needs.

- Implementing fall precautions to keep patients safe.

- Answering call lights promptly and consistently providing a calm, comfortable environment to make patients feel secure.

- Respecting patients’ belongings and asking their preferences for grooming, bathing, and meals to satisfy self-esteem needs.

- Encouraging interaction with patients to promote a feeling of belongingness.

- Respecting religious activities or referring patients to chaplain visits to promote self-actualization and a feeling of belongingness.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs can also be applied to the work environment to enhance professionalism by doing the following:

- Offering assistance to coworkers when able to promote a feeling of security and belongingness and also maintaining patients’ physiological needs and safety as a team.

- Accurately following training and agency policies and procedures to encourage feelings of self-esteem in the health care worker.

- Being accountable for one’s actions and job responsibilities to promote a feeling of self-actualization by meeting one’s potential.

Erikson’s Stages of Development

Another psychologist named Erik Erikson created a theory of psychosocial development that also describes how one’s personality is developed. It theorizes there are eight stages of development based on a person’s chronological age. Development occurs based on the main conflict or challenge confronted during that period of time. Each stage can create either a virtue/strength or a maladaptive tendency. Erikson proposed that those who have a stronger sense of identity from resolving these conflicts over time have fewer conflicts within themselves and with others and, subsequently, a decreased level of anxiety.[4]

Erikson’s stages of development are defined as trust versus mistrust, autonomy versus shame, initiative versus guilt, industry versus inferiority, identity versus identity confusion, intimacy versus isolation, generativity versus stagnation, and integrity versus despair[5]:

- Trust vs. Mistrust

The first stage establishes trust (or mistrust) that basic needs, such as nourishment and affection, will be met. Trust is the basis of our development during infancy (birth to 12 months). Infants are dependent on their caregivers, so caregivers who are responsive and sensitive to their infant’s needs help their baby to develop a sense of trust; their baby will see the world as a safe, predictable place. Unresponsive caregivers who do not meet their baby’s needs can engender feelings of anxiety, fear, and mistrust; their baby may see the world as unpredictable.[6]

- Autonomy vs. Shame

Toddlers begin to explore their world and learn that they can control their actions and act on the environment to get results. They begin to show clear preferences for certain elements of the environment, such as food, toys, and clothing. A toddler’s main task is to resolve the issue of autonomy versus shame and doubt by working to establish independence. For example, we might observe a budding sense of autonomy in a two-year-old child who wants to choose her clothes and dress herself. Although her outfits might not be appropriate for the situation, her input in such basic decisions has an effect on her sense of independence. If denied the opportunity to act on her environment, she may begin to doubt her abilities, which could lead to low self-esteem and feelings of shame.[7]

- Initiative vs. Guilt

Once children reach the preschool stage (ages 3–6 years), they are capable of initiating activities and asserting control over their world through social interactions and play. By learning to plan and achieve goals while interacting with others, preschool children can master this task. Those who do will develop self-confidence and feel a sense of purpose. Those who are unsuccessful at this stage may develop feelings of guilt.[8]

- Industry vs. Inferiority

During the elementary school stage (ages 7–11), children begin to compare themselves to their peers to see how they measure up. They either develop a sense of pride and accomplishment in their schoolwork, sports, social activities, and family life, or they feel inferior and inadequate when they don’t measure up.[9]

- Identity vs. Identity Confusion

In adolescence (ages 12–18), children develop a sense of self. Adolescents struggle with questions such as “Who am I?” and “What do I want to do with my life?” Along the way, most adolescents try on many different selves to see which ones fit. Adolescents who are successful at this stage have a strong sense of identity and are able to remain true to their beliefs and values in the face of problems and other people’s perspectives. Teens who do not make a conscious search for identity or those who are pressured to conform to their parents’ ideas for the future may have a weak sense of self and experience role confusion as they are unsure of their identity and confused about the future.[10]

- Intimacy vs. Isolation

People in early adulthood (i.e., 20s through early 40s) are ready to share their lives with others after they have developed a sense of self. Adults who do not develop a positive self-concept in adolescence may experience feelings of loneliness and emotional isolation.[11]

- Generativity vs. Stagnation

When people reach their 40s, they enter a time period known as middle adulthood that extends to the mid-60s. The social task of middle adulthood is generativity versus stagnation. Generativity involves finding your life’s work and contributing to the development of others, through activities such as volunteering, mentoring, and raising children. Those who do not master this task may experience stagnation, having little connection with others and little interest in productivity and self-improvement.[12]

- Integrity vs. Despair

The mid-60s to the end of life is a period of development known as late adulthood. People in late adulthood reflect on their lives and feel either a sense of satisfaction or a sense of failure. People who feel proud of their accomplishments feel a sense of integrity and often look back on their lives with few regrets. However, people who are not successful at this stage may feel as if their life has been wasted. They focus on what “would have,” “should have,” or “could have” been. They face the end of their lives with feelings of bitterness, depression, and despair.[13]

By combining Maslow’s and Erickson’s theories of development and motivation, we can begin to understand why some patients need more encouragement, space, or time to allow caregivers to provide care to maintain physical and emotional health.

View the following YouTube video[14] for more information about Erikson’s theory of development: Erikson’s Psychosocial Development | Individuals and Society.

Assisting With Spiritual Needs

When patients experience a serious illness or injury, they often grapple with the existential question, “Why is this happening to me?” This question can be a sign of spiritual distress defined as, “A state of suffering related to the inability to experience meaning in life through connections with self, others, the world, or a superior being.” Spiritual well-being is a pattern of experiencing meaning and purpose in life through connectedness with self, others, art, music, literature, nature, and/or a power greater than oneself. Spirituality is often mistakenly equated with religion, but spirituality is a broader concept. Elements of spirituality include faith, meaning, love, belonging, forgiveness, and connectedness.[15] Spirituality and religion can change over a person’s lifetime and vary greatly between people. Some people who are very spiritual may not belong to a specific religion.

Religion is frequently defined as an institutionalized set of beliefs and practices. Many religions have specific rules about food, religious rituals, clothing, and touching. Supporting these rules when they are a meaningful part of a patient’s spirituality is an effective way to support the patient and maintain a caring, professional relationship. The healthcare worker should discuss these aspects with their supervisor to assure they support the plan of care for the patient and encourage other staff members to provide support.

Many healthcare institutions employ professionally trained chaplains to assist with the spiritual, religious, and emotional needs of clients, family members, and staff. In these settings, chaplains support and encourage people of all religious faiths and cultures and customize their approach to each individual’s background, age, and medical condition. Chaplains can meet with any individual regardless of their belief, or lack of belief, in a higher power and can be very helpful in reducing anxiety and distress.[16] NAs may suggest chaplain services for their clients.

An important way to assist a client with their spiritual well-being is to ask them what they need to feel supported in their faith and then try to accommodate their requests, if possible. Explain that spiritual health helps the healing process. For example, perhaps they would like to speak to their clergy, spend some quiet time in meditation or prayer without interruption, or go to the on-site chapel. [17]

If the patient or family member requests a healthcare worker to pray with them, it is acceptable to pray with them or find someone who will. Some healthcare workers may feel reluctant to pray with patients when they are asked for various reasons; they may feel underprepared, uncomfortable, or unsure if they are “allowed to.” Health care team members are encouraged to pray with their patients to support their spiritual health, as long as the focus is on the patient’s preferences and beliefs, not their own preferences. Having a short, simple prayer ready that is appropriate for any faith may help a health care professional feel prepared for this situation. However, if the nursing assistant does not feel comfortable praying with the patient as requested, the nurse should be notified so the chaplain can be requested to participate in prayer with the patient.[18]

It is important to support clients within their own faith tradition, but it is not appropriate for the healthcare worker to take this opportunity to attempt to persuade a patient towards a preferred religion or belief system. The role of the healthcare worker is to respect and support the patient’s values and beliefs, not promote the healthcare worker’s values and beliefs.[19]

Attribution

This section contains content taken from Nursing Assistant by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- “Maslow%27s_Hierarchy_of_Needs2.svg” by Androidmarsexpress is licensed under CC.BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- McLeod, S. (2020, March 20). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html ↵

- Puchalski, C. M., Vitillo, R., Hull, S. K., & Reller, N. (2014). Improving the spiritual dimension of whole person care: Reaching national and international consensus. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 17(6), 642–656. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2014.9427 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Orenstein and Lewis and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Psychology 2e by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Psychology 2e by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Psychology 2e by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Psychology 2e by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Psychology 2e by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Psychology 2e by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Psychology 2e by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Psychology 2e by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Psychology 2e by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Desai, S. (2014, February 25). Erikson’s psychosocial development | Individuals and society | MCAT | Khan Academy [Video]. YouTube. Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA. https://youtu.be/SIoKwUcmivk ↵

- Herdman, T. H., & Kamitsuru, S. (Eds.). (2018). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification, 2018-2020. Thieme Publishers New York, pp. 365, 372-377. ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵