4.1 Emergency Preparedness, Response, and Recovery

A disaster is defined as a serious disruption of the functioning of a community or a society at any scale due to hazardous events interacting with conditions of exposure, vulnerability, and capacity that lead to human, material, economic, and environmental losses and impacts.[1] Every community must prepare to respond to disasters that include natural events (e.g., tornadoes, hurricanes, floods, wildfires, earthquakes, or disease outbreaks), man-made events (e.g., harmful chemical spills, mass shootings, or terrorist attacks), or infectious disease outbreaks. See Figure 4.1[2] for an image of the effects of the natural disaster Hurricane Katrina.

Emergency preparedness is the planning process focused on avoiding or reducing the risks and hazards resulting from a disaster to optimize population health and safety. Disaster management refers to the integration of emergency response plans throughout the life cycle of a disaster event. Because disasters cause physical and psychological effects in a community, emergency preparedness and disaster management emphasize collaboration and cooperative aid among health care institutions and community agencies to ensure a coordinated and effective response.[3]

Read the American Nurses Association resource regarding Disaster Preparedness.

Emergency preparedness and disaster management are based on four key concepts: preparedness, mitigation, response, and recovery. This process guides decision-making when an emergency or disaster occurs in a community.[4] After the disaster event has concluded, evaluation of the effectiveness of the response occurs as part of planning emergency preparedness. See Figure 18.3[5] for a diagram that illustrates this theoretical framework for emergency preparedness. Each of these concepts is further discussed in the following subsections.

Preparedness

Preparedness includes planning, training personnel, and providing educational activities regarding potential disastrous events. Planning includes evaluating environmental risks and social vulnerabilities of a community. Environmental risk refers to the probability and consequences of an unwanted accident in the environment in which community members live, work, or play. Risk assessment also includes assessing social vulnerabilities that affect community resilience.[6]

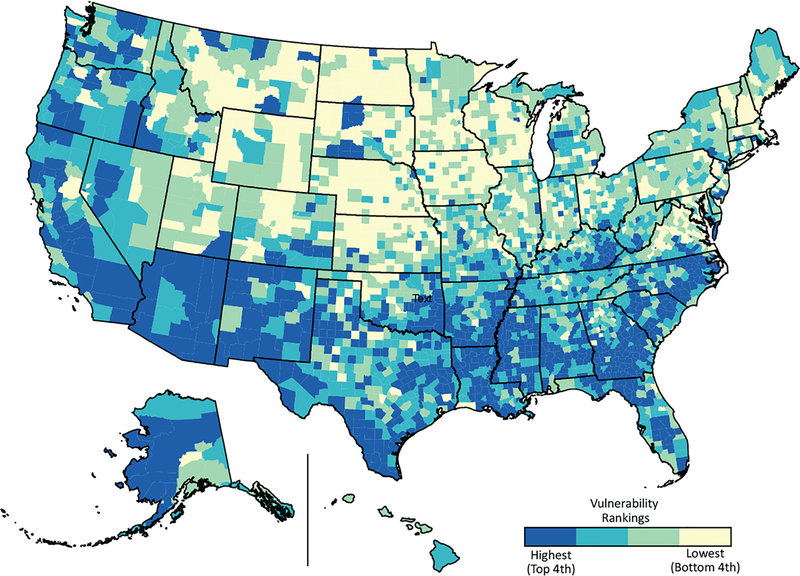

Social vulnerability refers to the characteristics of a person or a community that affect their capacity to anticipate, confront, repair, and recover from the effects of a disaster.[7] Populations living in a disaster-stricken area are not affected equally. Many factors can weaken community members’ ability to respond to disasters, including poverty, lack of access to transportation, and crowded housing. Evidence indicates that those living in poverty are more vulnerable at all stages of a catastrophic event, as are racial and ethnic minorities, children, elderly, and disabled people.[8] Socially vulnerable communities are more likely to experience higher rates of mortality, morbidity, and property destruction and are less likely to fully recover in the wake of a disaster compared to communities that are less socially vulnerable. Community health nurses must plan emergency responses to disasters that address these social vulnerabilities to decrease human suffering and financial loss.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) created a Social Vulnerability Index database and mapping tool designed to assist state, local, and tribal disaster management officials in identifying the locations of their most socially vulnerable populations. Geographic patterns of social vulnerabilities can be used in all phases of emergency preparedness and disaster management. See Figure 4.3[9] for an image of social vulnerability mapping.

Mitigation

Mitigation refers to actions taken to prevent or reduce the cause, impact, and consequences of disasters. Health care institutions and community health agencies plan three Cs to mitigate the effects of a disaster:

- Communication: An emergency communication plan identifies tools, resources, teams, and strategies to ensure effective actions during emergencies.

- Coordination: Coordination plays a crucial role in efficiency and effectiveness of disaster management by providing a big picture of an emergency and reducing uncertainty levels among responders.

- Collaboration: Collaboration allows responders to act together smoothly and helps reduce impact of the disaster.

Response

The response phase occurs in the immediate aftermath of a disaster. When a disaster occurs, actions are taken to save lives, treat injuries, and minimize the effect of the disaster. Immediate needs are addressed, such as medical treatment, shelter, food, and water, as well as psychological support of survivors. Personal safety and well-being in an emergency and the duration of the response phase depend on the level of a community’s preparedness. Examples of response activities include implementing disaster response plans, conducting search and rescue missions, and taking actions to protect oneself, family members, pets, and other community members.[10]

While the immediate actions of responding to a disaster are treating physical injuries, psychological effects must be addressed as well. To minimize psychological effects, nurses and first responders can provide support to victims of the disaster by following these tips from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)[11]:

- Promote safety: Ensure basic needs are met and provide simple instructions about how to receive these basic needs.

- Promote calm: Listen to people express their feelings and provide empathy and compassion even if they are angry, upset, or acting out. Offer objective information about the situation and efforts being made to help those affected by the disaster.

- Promote connectedness: Help people connect with friends, family members, and other loved ones. Keep families and family units together as best as possible, especially by keeping children with those whom they feel safe.

- Promote self-efficacy: Give suggestions about how people can help themselves and guide them toward the resources available. Encourage families and individuals to help meet their own needs.

- Promote help and hope: Know what services available and direct people are to those services and continue to update people about what is being done. When people are worried or scared, remind them that help is on the way.

Disaster Response Protocols

When thinking about responding to a disaster, first responders and emergency personnel come to mind such as law enforcement, fire departments, and emergency medical technicians (EMTs). However, many healthcare workers are also called upon to assist in emergencies or disasters and must be competent in responding. Any healthcare worker may be involved in triaging individuals for treatment.

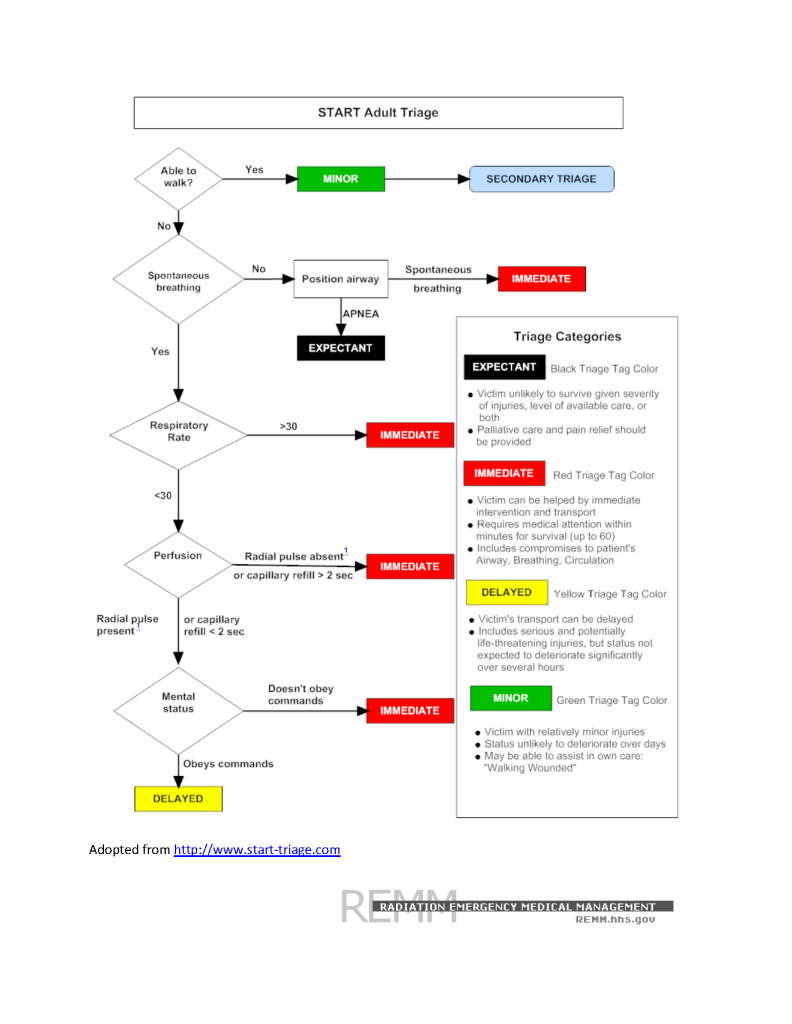

To respond effectively when a disaster occurs, emergency responders perform triage by prioritizing treatment for individuals affected by the disaster or emergency. Field triage sorts victims affected by the event and ranks victims based on the severity of their symptoms. Disaster triage determines the severity of injuries suffered by victims and then systematically distributes them to local health care facilities based on their severity.

Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment (START) is an example of a triage system established by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services that prioritizes treatment of victims by using standard colors indicating the severity of symptoms and prognosis. See Figure 4.4[12] for the START algorithm. The following colors indicate severity of injury and prognosis:

- RED: Emergent needs

- Life-threatening needs, such as alterations in airway, breathing, and circulation; impairment in neurological systems; or severe, life-threatening injuries.

- They may have less than 60 minutes to survive.

- These patients will be seen first or immediately.

- YELLOW: Urgent, but delayed needs

- Life-threatening needs; status is not anticipated to change quickly or significantly in the next hours, so transport can be delayed.

- GREEN: Non-urgent needs, often referred to as the “walking wounded”

- Minor injuries; status is not likely to deteriorate over the next several days.

- Many individuals can assist with obtaining their own care.

- BLACK: The person has died or is expected to die soon

- This person is unlikely to survive given the severity of their injuries, level of available care, or both.

- Palliative care and pain relief should be provided.

Providing Care for Those Exposed to Environmental Hazards

Healthcare wokers may be involved in caring for clients who have been exposed to chemicals or other environmental hazards. See Table 18.3 for assessment findings and interventions for a variety of exposures. Chelation therapy is a treatment indicated for heavy metal poisoning such as mercury, arsenic, and lead. Chelators are medications that bind to the metals in the bloodstream to increase urinary excretion of the substance.

Some chemical exposures require decontamination to treat the individual, as well as to protect others around them, including first responders, nurses, and other patients. Decontamination is any process that removes or neutralizes a chemical hazard on or in the patient to prevent or mitigate adverse health effects to the patient; protect emergency first responders, health care facility first receivers, and other patients from secondary contamination; and reduce the potential for secondary contamination of response and health care infrastructure. For example, if a farmer enters a rural hospital’s emergency department after chemical exposure to an insecticide spray, decontamination may be required. See Figure 4.5[13] for an image of decontamination.

The decision to decontaminate an individual should take into account a combination of these key indicators[14]:

- Signs and symptoms of exposure displayed by the patient

- Visible evidence of contamination on the patient’s skin or clothing

- Proximity of the patient to the location of the chemical release

- Contamination detected on the patient using appropriate detection technology

- The chemical and its properties

- Request by the patient for decontamination, even if contamination is unlikely

| Chemical or Hazard | Assessment Findings | Interventions |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon Monoxide (CO) Poisoning

(Auto exhaust and improperly vented or malfunctioning furnaces or fuel-burning devices)[15] |

Primarily decreased mental status from confusion to coma

May have cherry-red appearance of the lips and skin *Note: Pulse oximetry does not reflect accurate oxygenation levels because CO binds to hemoglobin. |

|

| Lead Poisoning

(Lead-contaminated paint dust, water, or food and bullets in wild game)[16],[17] |

Abdominal pain, constipation, fatigue, joint pain, muscle pain, headache, anemia, memory deficits, psychiatric symptoms, elevated blood pressure, decreased kidney function, decreased sperm count, increased mortality

*Note: Some symptoms may be irreversible. |

|

| Formaldehyde Poisoning

(Construction and agriculture products and disinfectants)[18] |

Eye and skin irritation, abdominal pain, bronchospasm, shortness of breath, decreased respiratory rate, acute kidney failure |

|

| Arsenic Poisoning

(Contaminated groundwater, tobacco smoke, hide tanning, and pressure treated wood)[19],[20] |

Nausea/vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, paresthesias, muscle cramping, skin pigmentation changes, skin lesions and cancers, cardiac dysrhythmias, death |

|

| Mercury

(Thermometers, sphygmomanometers, fluorescent light bulbs, amalgam tooth fillings, and contaminated fish)[21] |

Acute inhalation exposure in occupational settings may cause cough, dyspnea, chest pain, excessive salivation, inflammation of gums, severe nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, dermatitis |

|

| Radon Gas

(Naturally occurring gas resulting from the decay of trace amounts of uranium found in the earth’s crust)[22] |

Persistent cough, hoarseness, wheezing, shortness of breath, coughing up blood, chest pain, frequent respiratory infections like bronchitis and pneumonia, loss of appetite, weight loss, fatigue, lung cancer |

|

| Infectious Disease

(HIV, hepatitis, sexually transmitted diseases, and COVID-19) |

Symptoms are based on disease process |

|

| Frostbite

(Overexposure of skin to cold)[23] |

White or grayish color of exposed skin, may be hard or waxy to touch; lack of sensitivity to touch or numbness and tingling; clear or blood-filled blisters after thawing; cyanosis after rewarming indicates necrosis |

|

| Organophosphates

(Insecticides and bioterrorism nerve agents)[24] |

Acute onset of symptoms related to cholinergic excess: bradycardia, increased salivation, tearing, urination, vomiting and diarrhea, diaphoresis, paralysis, respiratory failure, hypotension, seizures

Intermediate syndrome: neck flexion weakness, cranial nerve abnormalities, muscle weakness |

|

| Bioterrorism

(Anthrax, smallpox, nerve agents, and ricin)[25] |

Symptoms are based on the agent |

|

Access up-to-date, evidence-based information for suspected poisoning at the Poison Control Center or call 1-800-222-1222.

Read more about Patient Decontamination in a Mass Chemical Exposure Incident by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Recovery

During the recovery period, restoration efforts occur concurrently with regular operations and activities. The recovery period from a disaster can be prolonged. Examples of recovery activities include the following[26]:

- Preventing or reducing stress-related illnesses and excessive financial burdens

- Rebuilding damaged structures

- Reducing vulnerability to future disasters

When people are affected by a disaster, they may respond in a variety of different ways. It is natural and expected to respond to a disaster with emotions such as fear, worry, sadness, anxiety, depression, and despair. Many people exhibit resiliency, the ability to cope with adversity and recover emotionally from a traumatic event.[27] However, the mental health of the population must be considered and monitored during recovery from any disastrous event. For example, some people may relive previous traumatic experiences or revert to using substances to cope. Behavioral health responses such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), substance use disorder, and increased risk for suicide should always be considered when assessing individuals’ responses to a disaster.

Effects from trauma extend beyond the physical damages from any disaster. It may take time for individuals to recover physically and emotionally. Survivors of a community disaster should be encouraged to take steps to support each other to promote adaptive coping. Use the following box to read additional information in the “Tips for Survivors of a Traumatic Event” handout by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

Read the SAMHSA handout on “Tips for Survivors of a Traumatic Event” PDF.

Review concepts related to loss and the stages of grief in the “Grief and Loss” chapter of Open RN Nursing Fundamentals.

Agencies Providing Emergency Assistance

Many federal, state, and local agencies provide support to communities during disasters. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) is the agency that promotes disaster mitigation and readiness and coordinates response and recovery following the declaration of a major disaster. FEMA defines a disaster as an event that results in large numbers of deaths and injuries; causes extensive damage or destruction of facilities that provide and sustain human needs; produces an overwhelming demand on state and local response resources and mechanisms; causes a severe long-term effect on general economic activity; and severely affects state, local, and private sector capabilities to begin and sustain response activities.[28] FEMA employees represent every U.S. state, local, tribal, and territorial area and are committed to serving our country before, during, and after disasters.

Disasters are declared using established guidelines and procedures. Because all disasters are local, they are initially declared at the local level. This declaration is typically made by the local mayor. When the mayor determines that capabilities of local resources have been or are expected to be exceeded, state assistance is requested. If the state chooses to respond to a disaster, the governor of the state will direct implementation of the state’s emergency plan. If the governor determines that the resource capabilities of the state are exceeded, the governor can request that the president declare a major disaster in order to make federal resources and assistance available to qualified state and local governments. This ordered sequence is important to ensure appropriate financial assistance.[29]

A state of emergency is declared when public health or the economic stability of a community is threatened, and extraordinary measures of control may be needed. For example, an infectious disease outbreak like COVID-19 can cause the declaration of a state of emergency. A county or municipal agency is designated as the local emergency management agency, and local law specifies the chain of command in emergencies. Use the following box to access more information about federal and local agencies that provide emergency assistance.

Examples of Organizations That Provide Emergency Assistance

Federal

Local

- Local FEMA agencies (each state)

- American Red Cross

- Local county emergency management divisions

Attribution

This section contains content taken from Nursing: Mental Health and Community Concepts by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2021). The future of nursing 2020-2030: Charting a path to achieve health equity. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25982 ↵

- “LA_1603_9thDistDam121.jpg” by Booher, Andrea, Photographer is in the Public Domain. ↵

- Savage, C. L. (2020). Public/community health and nursing practice: Caring for populations (2nd ed.). FA Davis. ↵

- Emergency Management Institute. (2013). ISS-111.A: Livestock in disasters. Federal Emergency Management Agency. https://training.fema.gov/emiweb/downloads/is111_unit%204.pdf ↵

- “Environmental Health and Emergency Preparedness” by Dawn Barone for Open RN is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Flanagan, B. E., Hallisey, E. J., Adams, E., & Lavery, A. (2018). Measuring community vulnerability to natural and anthropogenic hazards: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's social vulnerability index. Journal of Environmental Health, 80(10). 34–36. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7179070/ ↵

- Flanagan, B. E., Hallisey, E. J., Adams, E., & Lavery, A. (2018). Measuring community vulnerability to natural and anthropogenic hazards: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's social vulnerability index. Journal of Environmental Health, 80(10). 34–36. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7179070/ ↵

- Flanagan, B. E., Hallisey, E. J., Adams, E., & Lavery, A. (2018). Measuring community vulnerability to natural and anthropogenic hazards: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's social vulnerability index. Journal of Environmental Health, 80(10). 34–36. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7179070/ ↵

- This image is derivative of Flanagan, B. E., Hallisey, E. J., Adams, E., & Lavery, A. (2018). Measuring community vulnerability to natural and anthropogenic hazards: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's social vulnerability index. Journal of Environmental Health, 80(10), 34–36. Access the report at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7179070/ ↵

- Emergency Management Institute. (2013). ISS-111.A: Livestock in disasters. Federal Emergency Management Agency. https://training.fema.gov/emiweb/downloads/is111_unit%204.pdf ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2005). Psychological first aid for first responders. [Handout]. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://store.samhsa.gov/product/Psychological-First-Aid-for-First-Responders/NMH05-0210 ↵

- “StartAdultTriageAlgorithm.png” by unknown author at CHEMM is in the Public Domain. ↵

- “decontamination26.jpg” by Benjamin Crossley CDP/FEMA is in the Public Domain. ↵

- U.S. Department of Homeland Security, & U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2014). Patient decontamination in a mass chemical exposure incident: National planning guidance for communities. http://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/responders/Documents/patient-decon-natl-plng-guide.pdf ↵

- Clardy, P. F., & Manaker, S. (2021, June 17). Carbon monoxide poisoning. UpToDate. Accessed April 3, 2022, from www.update.com ↵

- World Health Organization. (2021, October 11). Lead poisoning. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/lead-poisoning-and-health ↵

- Goldman, R. H., & Hu, H. (2021, November 4). Lead exposure and poisoning in adults. UpToDate. Accessed April 3, 2022, from www.update.com ↵

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. (2014, October 21). Medical management guidelines for formaldehyde. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/TSP/MMG/MMGDetails.aspx?mmgid=216&toxid=39 ↵

- World Health Organization. (2018, February 15). Arsenic. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/arsenic ↵

- Goldman, R. H. (2020, October 8). Arsenic exposure and poisoning. UpToDate. Accessed April 3, 2022, from www.update.com ↵

- Beauchamp, G., Kusin, S., & Elinder, C. (2022, February 1). Mercury toxicity. UpToDate. Accessed April 3, 2022, from www.update.com ↵

- National Radon Defense. (n.d.). Radon symptoms. https://www.nationalradondefense.com/radon-information/radon-symptoms.html ↵

- Zafren, K., & Mechem, C. C. (2021, February 1). Frostbite: Emergency care and prevention. UpToDate. Accessed April 3, 2022, from www.update.com ↵

- Bird, S. (2021, September 23). Organophosphate and carbamate poisoning. UpToDate. Accessed April 3, 2022, from www.update.com ↵

- Adalja, A. A. (2022, January 10). Identifying and managing casualties of biological terrorism. UpToDate. Accessed April 3, 2022, from www.update.com ↵

- Emergency Management Institute. (2013). ISS-111.A: Livestock in disasters. Federal Emergency Management Agency. https://training.fema.gov/emiweb/downloads/is111_unit%204.pdf ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2022, March 23). Disaster preparedness, response, and recovery. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.samhsa.gov/disaster-preparedness ↵

- Emergency Management Institute. (2013). ISS-111.A: Livestock in disasters. Federal Emergency Management Agency. https://training.fema.gov/emiweb/downloads/is111_unit%204.pdf ↵

- Emergency Management Institute. (2013). ISS-111.A: Livestock in disasters. Federal Emergency Management Agency. https://training.fema.gov/emiweb/downloads/is111_unit%204.pdf ↵