3.4 Teams and Teamwork

IPEC Competencies

The fourth IPEC competency states, “Apply relationship-building values and the principles of team dynamics to perform effectively in different team roles to plan, deliver, and evaluate patient/population-centered care and population health programs and policies that are safe, timely, efficient, effective, and equitable.”[1] See the following box for the components of this IPEC competency.

Components of IPEC’s Teams and Teamwork Competency[2]

- Describe the process of team development and the roles and practices of effective teams.

- Develop consensus on the ethical principles to guide all aspects of teamwork.

- Engage health and other professionals in shared patient-centered and population-focused problem-solving.

- Integrate the knowledge and experience of health and other professions to inform health and care decisions, while respecting patient and community values and priorities/preferences for care.

- Apply leadership practices that support collaborative practice and team effectiveness.

- Engage self and others to constructively manage disagreements about values, roles, goals, and actions that arise among health and other professionals and with patients, families, and community members.

- Share accountability with other professions, patients, and communities for outcomes relevant to prevention and health care.

- Reflect on individual and team performance for individual, as well as team, performance improvement.

- Use process improvement to increase effectiveness of interprofessional teamwork and team-based services, programs, and policies.

- Use available evidence to inform effective teamwork and team-based practices.

- Perform effectively on teams and in different team roles in a variety of settings.

Why is teamwork important in healthcare?

Developing effective teams is critical for providing health care that is patient-centered, safe, timely, effective, efficient, and equitable.[3] [4] for an image illustrating interprofessional teamwork.

A patient can directly see at least 18 different healthcare professionals a day. This number may not include healthcare workers such as sterile processing technicians, pharmacy technicians, and food service workers that do not see the patients face to face but have a direct impact on their care. It is then clear why teamwork is essential to quality patient-centered care. As a healthcare employee you will be required to work with multiple people in various different roles.

Understanding the importance of a team allows us to see how dangerous poor teamwork can be to a patient. Poor work relationships and lack of teamwork don’t only result in tears or hurt feelings. A lack of teamwork can cause actual harm, and even death, to patients. Picture a nurse and physician that do not get along. The nurse does not like to speak to the physician because he is rude and snaps at her every time they communicate. The dysfunctional relationship takes center stage, above the patient, and important health related information is not relayed about the patient. This is one example of how poor teamwork may affect the patient.

Poor teamwork can also harm employees. Those who work in the health care system at every level can be the victims of poor teamwork. They often experience physical and emotional problems when teamwork lacks respect. It is not unusual to hear someone say they want to quit their job because of another coworker, or due to a “toxic work environment”. Hospitals may lose quality employees to a lack of effective teamwork, creating a culture of constant change and instability.

Qualities of a successful team are described in the following box.[5]

Qualities of A Successful Team[6]

- Promote a respectful atmosphere

- Define clear roles and responsibilities for team members

- Regularly and routinely share information

- Encourage open communication

- Implement a culture of safety

- Provide clear directions

- Share responsibility for team success

- Balance team member participation based on the current situation

- Acknowledge and manage conflict

- Enforce accountability among all team members

- Communicate the decision-making process

- Facilitate access to needed resources

- Evaluate team outcomes and adjust as needed

Psychological Safety

An effective team creates an environment that allows EVERY member to speak up with questions or concerns. This is called Psychological safety. Research shows that 20% of US healthcare workers are hesitant to speak up about patient safety. Another study discusses team members who reported seeing the same mistakes happening over and over again with no way to discuss and resolve them. In order to create a strong team, we must assure every healthcare worker feels safe enough to speak up when needed.

Healthcare, like many industries, has a hierarchy system based on education and experience. This system has entry level skilled workers at the bottom, mid level professionals in the middle, and continues to the physician at the top. Looking at the operating room, a typical OR team can consist of a Patient Care Technician (1 semester of higher education), a Surgical Technologist (2 years of higher education), a circulator nurse (4 years of higher education), a physician assistant (6 years of higher education), an anesthesiologist (10 years higher education and residency), and a surgeon who can have over 12 years of education and training. While all healthcare workers are skilled in their specific roles, the surgeon, the most qualified member of the team, is considered the team leader. The surgeon sets the stage and issues direction in times of crisis. Now, picture this room without recognizing the hierarchy of skills and education, there would be no clear leader, and someone who is not appropriately educated or licensed, could take charge and lead the team in the wrong direction. So hierarchy has a purpose in healthcare and it should be respected.

That said, while respecting the different positions within the hierarchy, it is equally important for every member, regardless of placement on the pyramid, to respect the skill and ability of each member of the team, and allow them to speak freely if they witness a mistake within their scope of practice.

Health care, as a culture, places great emphasis on being right and knowing the answers. No one wants to look as if they do not know what they are doing. And anyone who has ever been unsupported, humiliated, or disciplined for speaking up, is definitely less willing to do it a second time, no matter the risk to the patient. This means that healthcare leaders must set a positive tone that invites all team members into the conversation so they feel comfortable sharing their concerns and ideas.

Patient Advocacy is a Team Sport!

An Advocate is defined as a defender of a cause, or another person, or as someone who speaks or writes to support something. Because a person cannot advocate by thinking something and keeping it to oneself, or wishing a patient well and hoping bad things don’t happen, advocacy means taking some kind of public stand, and speaking out.

Advocacy involves the outright refusal to leave patients to fend for themselves. And We know that failure of advocacy not only leads to frustration but also to below standard of care and possibly even avoidable harm. One reason that advocacy is such a challenge is that it has been identified as an individual responsibility rather than as a team activity. If we work as a team, we will be better patient advocates for the patient.

Often allied health professionals, those who are on the low end of the pyramid, are closest to the patient, or the patient’s care, throughout the day. Due to this fact, we may see things that the nurses or doctors do not see. It is important we maintain strong healthy team relationships, and have the confidence and strength to speak up when observing a problem.

Feedback

Feedback is provided to a team member for the purpose of improving team performance. Effective feedback should follow these parameters[7]:

- Timely: Provided soon after the target behavior has occurred.

- Respectful: Focused on behaviors, not personal attributes.

- Specific: Related to a specific task or behavior that requires correction or improvement.

- Directed towards improvement: Suggestions are made for future improvement.

- Considerate: Team members’ feelings should be considered and privacy provided. Negative information should be delivered with fairness and respect.

Advocating for Safety with Assertive Statements

When a team member perceives a potential patient safety concern, they should assertively communicate with the decision-maker to protect patient safety. This strategy holds true for ALL team members, no matter their position within the hierarchy of the health care environment. The message should be communicated to the decision-maker in a firm and respectful manner using the following steps[8]:

- Make an opening.

- State the concern.

- State the problem (real or perceived).

- Offer a solution.

- Reach agreement on next steps.

Examples of Using Assertive Statements to Promote Patient Safety

A nurse notices that a team member did not properly wash their hands during patient care. Feedback is provided immediately in a private area after the team member left the patient room: “I noticed you didn’t wash your hands when you entered the patient’s room. Can you help me understand why that didn’t occur?” (Wait for an answer.) “Performing hand hygiene is essential for protecting our patients from infection. It is also hospital policy and we are audited for compliance to this policy. Let me know if you have any questions and I will check back with you later in the shift.” (Monitor the team member for appropriate hand hygiene for the remainder of the shift.)

Two-Challenge Rule

When an assertive statement is ignored by the decision-maker, the team member should assertively voice their concern at least two times to ensure that it has been heard by the decision-maker. This strategy is referred to as the two-challenge rule. When this rule is adopted as a policy by a health care organization, it empowers all team members to pause care if they sense or discover an essential safety breach. The decision-maker being challenged is expected to acknowledge the concern has been heard.[9]

CUS Assertive Statements

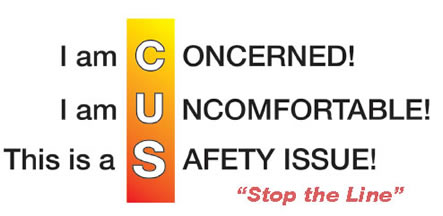

During emergent situations, when stress levels are high or when situations are charged with emotion, the decision-maker may not “hear” the message being communicated, even when the two-challenge rule is implemented. It is helpful for agencies to establish assertive statements that are well-recognized by all staff as implementation of the two-challenge rule. These assertive statements are referred to as the CUS mnemonic: “I am Concerned – I am Uncomfortable – This is a Safety issue!”[10] See Figure 7.8[11] for an illustration of CUS assertive statements.

Using these scripted messages may effectively catch the attention of the decision-maker. However, if the safety issue still isn’t addressed after the second statement or the use of “CUS” assertive statements, the team member should take a stronger course of action and utilize the agency’s chain of command. For the two-challenge rule and CUS assertive statements to be effective within an agency, administrators must support a culture of safety and emphasize the importance of these initiatives to promote patient safety.

Read an example of a nurse using assertive statements in the following box.

Assertive Statement Example

A nurse observes a new physician resident preparing to insert a central line at a patient’s bedside. The nurse notes the resident has inadvertently contaminated the right sterile glove prior to insertion.

Nurse: “Dr. Smith, I noticed that you contaminated your sterile gloves when preparing the sterile field for central line insertion. I will get a new set of sterile gloves for you.”

Dr. Smith: (Ignores nurse and continues procedure.)

Nurse: “Dr. Smith, please pause the procedure. I noticed that you contaminated your right sterile glove by touching outside the sterile field. I will get a new set of sterile gloves for you.”

Dr. Smith: “My gloves are fine.” (Prepares to initiate insertion.)

Nurse: “Dr. Smith – I am concerned! I am uncomfortable! This is a safety issue!”

Dr. Smith: (Stops procedure, looks up, and listens to the nurse.) “I’ll wait for that second pair of gloves.”

The coordination and delivery of safe, quality patient care demands reliable teamwork and collaboration across the organizational and community boundaries. Clients often have multiple visits across multiple providers working in different organizations. Communication failures between health care settings, departments, and team members is the leading cause of patient harm.[12] The health care system is becoming increasingly complex requiring collaboration among diverse health care team members.

The goal of good interprofessional collaboration is improved patient outcomes, as well as increased job satisfaction of health care team professionals. Patients receiving care with poor teamwork are almost five times as likely to experience complications or death. Hospitals in which staff report higher levels of teamwork have lower rates of workplace injuries and illness, fewer incidents of workplace harassment and violence, and lower turnover.[13]

Valuing and understanding the roles of team members are important steps toward establishing good interprofessional teamwork. Another step is learning how to effectively communicate with interprofessional team members.

Attribution

The section contains content taken from Nursing Management and Professional Concepts 2e by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- Interprofessional Education Collaborative. IPEC core competencies. https://www.ipecollaborative.org/ipec-core-competencies ↵

- Interprofessional Education Collaborative. IPEC core competencies. https://www.ipecollaborative.org/ipec-core-competencies ↵

- Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. (2011). Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: Report on an expert panel. Interprofessional Education Collaborative. https://ipec.memberclicks.net/assets/2011-Original.pdf ↵

- "400845937-huge.jpg" by Flamingo Images is used under license from Shutterstock.com ↵

- O’Daniel, M., & Rosenstein, A. H. (2011). Professional communication and team collaboration. In: Hughes R.G. (Ed.). Patient safety and quality: An evidence-based handbook for nurses. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); Chapter 33. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2637 ↵

- O’Daniel, M., & Rosenstein, A. H. (2011). Professional communication and team collaboration. In: Hughes R.G. (Ed.). Patient safety and quality: An evidence-based handbook for nurses. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); Chapter 33. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2637 ↵

- AHRQ. (2020, January). Pocket guide: TeamSTEPPS. https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/instructor/essentials/pocketguide.html ↵

- AHRQ. (2020, January). Pocket guide: TeamSTEPPS. https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/instructor/essentials/pocketguide.html ↵

- AHRQ. (2020, January). Pocket guide: TeamSTEPPS. https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/instructor/essentials/pocketguide.html ↵

- AHRQ. (2020, January). Pocket guide: TeamSTEPPS. https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/instructor/essentials/pocketguide.html ↵

- “cusfig1.jpg” by unknown author is licensed under Public Domain. Access for free at https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/instructor/essentials/pocketguide.html ↵

- Rosen, M. A., DiazGranados, D., Dietz, A. S., Benishek, L. E., Thompson, D., Pronovost, P. J., & Weaver, S. J. (2018). Teamwork in healthcare: Key discoveries enabling safer, high-quality care. The American Psychologist, 73(4), 433-450. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000298 ↵

- Rosen, M. A., DiazGranados, D., Dietz, A. S., Benishek, L. E., Thompson, D., Pronovost, P. J., & Weaver, S. J. (2018). Teamwork in healthcare: Key discoveries enabling safer, high-quality care. The American Psychologist, 73(4), 433-450. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000298 ↵