8 General Concepts

Intimate Partner Abuse Violence in romantic relationships is a significant concern for relationships throughout the lifespan. Statistically, women aged 18 to 34 generally experience the highest rates of intimate partner violence. According to the most recent Violence Policy Center (2018) study, more than 1,800 women were murdered by men in 2016. The study found that nationwide, 93% of women killed by men were murdered by someone they knew, and guns were the most common weapon used. The national rate of women murdered by men in single victim/single offender incidents dropped 24%, from 1.57 per 100,000 in 1996 to 1.20 per 100,000 in 2016. However, since reaching a low of 1.08 per 100,000 women in 2014, the 2016 rate increased by 11%. Intimate partner violence is often divided into situational couple violence, which is the violence that results when heated conflict escalates, and intimate terrorism, in which one partner consistently uses fear and violence to dominate the other (Bosson, et al., 2019). Men and women equally use and experience situational couple violence, while men are more likely to use intimate terrorism than are women. Additionally, female victims of intimate partner violence experience different patterns of violence, such as rape, severe physical violence, and stalking than male victims, who most often experienced more slapping, shoving, and pushing. The National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799-SAFE (7233) or go to The Hotline.org.

Preventing Sexual Violence

What is Sexual Violence?

Sexual violence is sexual activity when consent is not obtained or freely given. It is a serious public health problem in the United States that profoundly impacts lifelong health, opportunity, and well-being. Sexual violence impacts every community and affects people of all genders, sexual orientations, and ages. Anyone can experience or perpetrate sexual violence. The perpetrator of sexual violence is usually someone the victim knows, such as a friend, current or former intimate partner, coworker, neighbor, or family member.1

Sexual violence can occur in person, online, or through technology, such as posting or sharing sexual pictures of someone without their consent, or non-consensual sexting.

How big is the problem?

Sexual violence affects millions of people each year in the United States. Researchers know the numbers underestimate this problem as many cases are unreported. Survivors may be ashamed, embarrassed, or afraid to tell the police, friends, or family about the violence. Survivors may also keep quiet because they have been threatened with further harm if they tell anyone or do not think anyone will help them. The data shows:

- Sexual violence is common. Over half of women and almost 1 in 3 men have experienced sexual violence involving physical contact during their lifetimes. One in 4 women and about 1 in 26 men have experienced completed or attempted rape. About 1 in 9 men were made to penetrate someone during his lifetime. Additionally, 1 in 3 women and about 1 in 9 men experienced sexual harassment in a public place. 2

- Sexual violence starts early. More than 4 in 5 female rape survivors reported that they were first raped before age 25 and almost half were first raped as a minor (i.e., before age 18). Nearly 8 in 10 male rape survivors reported that they were made to penetrate someone before age 25 and about 4 in 10 were first made to penetrate as a minor.2

- Sexual violence disproportionately affects some groups. Women and racial and ethnic minority groups experience a higher burden of sexual violence. For example, more than 2 in 5 non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native and non=Hispanic multiracial women were raped in their lifetime. 2

- Sexual violence is costly. Recent estimates put the lifetime cost of rape at $122,461 per victim, including medical costs, lost productivity, criminal justice activities, and other costs.3

What are the consequences?

Sexual violence consequences are physical, like bruising and genital injuries, sexually transmitted infections, and pregnancy (for women)2 and psychological, such as depression, anxiety, and suicidal thoughts. 4

The consequences may be chronic. Survivors may suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder, and experience re-occurring reproductive, gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, and sexual health problems. 4 Sexual violence is also linked to negative health behaviors. Survivors are more likely to smoke, abuse alcohol, use drugs, and engage in risky sexual activity. 5

The trauma from sexual violence may impact a survivor’s employment in terms of time off from work, diminished performance, job loss, or inability to work. These disrupt earning power and have a long-term effect on the economic well-being of survivors and their families. Coping and completing everyday tasks after victimization can be challenging. Survivors may have difficulty maintaining personal relationships, returning to work or school, and regaining a sense of normalcy. 4

Additionally, sexual violence is connected to other forms of violence. For example, girls who have been sexually abused are more likely to experience additional sexual violence and other violence types and become victims of intimate partner violence in adulthood. 6

Bullying perpetration in early middle school is associated with sexual harassment perpetration in high school. 7

How can we prevent sexual violence?

Certain factors may increase or decrease the risk of perpetrating or experiencing sexual violence. To prevent sexual violence, we must understand and address the factors that put people at risk for or protect them from violence. 6 We must also understand how historical trauma and structural inequities impact health.2

CDC developed STOP SV: A Technical Package to Prevent Sexual Violence to help communities use the best available evidence to prevent sexual violence. This resource is available in English and Spanish and can impact individual behaviors and relationships, family, school, community, and societal factors that influence risk and protective factors for violence. Different violence types are connected and often share root causes. Sexual violence is linked to other violence types through shared risk and protective factors. Addressing and preventing one violence type may help prevent other violence types.

1-800-CDC-INFO (232-4636) • www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention

References

1. Basile KC, Smith SG, Breiding MJ, Black M C, & Mahendra, R. (2014). Sexual violence surveillance: uniform definitions and recommended data elements, Version 2.0. Atlanta (GA): National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

2. Basile KC, Smith SG, Kresnow M, Khatiwada S, & Leemis RW. (2022). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2016/2017 Report on Sexual Violence. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

3. Peterson C, DeGue S, Florence C, Lokey C. (2017). Lifetime Economic Burden of Rape in the United States. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 52(6): 691-701.

4. Basile KC and Smith SG. (2011). Sexual Violence Victimization of Women: Prevalence, Characteristics, and the Role of Public Health and Prevention. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine (5): 407-417.

5. Basile KC, Clayton HB, Rostad WL, & Leemis RW. (2020). Sexual violence victimization of youth and health risk behaviors. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 58(4), 570-579.

6. Preventing Multiple Forms of Violence: A Strategic Vision for Connecting the Dots. (2016). Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

7. Espelage DL, Basile KC, Hamburger ME. (2012). Bullying perpetration and subsequent sexual violence perpetration among middle school students. Journal of Adolescent Health 50(1): 60-65.

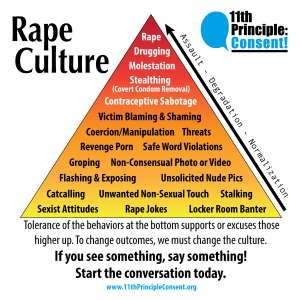

8. “Rape Culture Pyramid,” and “Gender Neutral” Creative Commons Licensed CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike), which means attribution is required for not-for-profit use. Please contact us for commercial use: https://www.11thprincipleconsent.org/consent-propaganda/rape-culture-pyramid/