22 Module 22: Intimate Relationships

This module is principally about the third part of the definition of social psychology, relating to other people. It is nowhere near an exhaustive list of the different ways that we relate with each other; rather it covers some of the close relationships that we have in our lives. In particular, We will be covering important aspects of intimate, often physical, relationships that many people have. Some related topics are covered elsewhere in the book. For example, friendship and parenting from Unit 4 are both important aspects of intimate relationships. Also, emotions and behaviors such as helping and aggression clearly are relevant to a discussion of how people relate to each other.

This module has three sections. Section 22.1 covers two key components of close physical relationships, namely love and sexual behavior. Section 22.2 describes the important progress we have made toward understanding sexual orientation, or the gender of people to whom we are sexually attracted. Section 22.3 covers some important observations about marriage, the specific long-term relationship in which love and sexual behavior play prominent roles.

22.1 Love and Sexual Behavior

22.2 Sexual Orientation

22.3 Marriage, and Divorce

READING WITH A PURPOSE

Remember and Understand

By reading and studying Module 22, you should be able to remember and describe:

- Characteristics of love/kinds of love (22.1)

- Why people fall in love physical attraction, similarity, mere exposure (22.1)

- Misconceptions about sex (22.1)

- Sexuality throughout the lifespan (22.1)

- Evolutionary psychology applied to sexual behavior: long-term and short-term mating strategies, and evolved preferences in mates (22.1)

- Sexual response cycle (22.1)

- Sexual orientation: different sexual orientations, genetic factors, rejected environmental explanations (22.2)

- Benefits of a good marriage, dangers of a bad marriage (22.3)

- What predicts and does not predict divorce (22.3)

- Strengthening marriage (22.3)

Apply

By reading and thinking about how the concepts in Module 22 apply to real life, you should be able to:

- If you have ever been in love, recognize the possible roles of physical attraction, similarity, and mere exposure (22.1)

- Recognize the phases of sexual response in yourself or a sexual partner (22.1)

- Recognize behaviors in yourself or others that are consistent with long-term and short-term mating strategies (22.1)

Analyze, Evaluate, and Create

By reading and thinking about Module 22, participating in classroom activities, and completing out-of-class assignments, you should be able to:

- If you have ever been in love, describe how Sternberg’s triangular theory and Berscheid and Hatfield’s passionate and companionate love apply to your relationship. (22.1)

- Articulate your response to the information about the causes of sexual orientation. If you agree, why do you agree? If you disagree, why do you disagree? (22.2)

- Apply John Gottman’s ideas about marriage to a long-term romantic relationship (successful or unsuccessful) in your own life (22.3)

22.1 Love and Sexual Behavior

Activate

- What is your opinion about the benefits of scientific research into the causes of love?

- Have you ever been in love? If so, what led you to fall in love? If not, what do you think will lead you to fall in love with someone?

- Do you think that US culture is too restrictive or too permissive about sexuality?

If people object to the scientific study of anything more than they object to the study of love, we cannot imagine what it would be. To many people, part of the appeal, the mystique, of love is that it is incomprehensible. Reducing something as wondrous and transcendent as love to psychological, or worse yet, biological, explanations seems to render it sterile and mundane. On top of that, it seems frivolous to try to study love. What possible benefit comes from discovering what leads to love? Recall from Module 4, a dubious distinction intended to signify a waste of US taxpayers’ money, was given to research about love (research, by the way, conducted by Ellen Berscheid, about whom you will read soon).

To put it mildly, we disagree with those who object to the scientific study of love. First of all, we are driven by a curiosity about what love is and what makes it happen or not happen. There is a practical reason for studying love as well. Approximately 40% of first and second marriages in the US end in divorce or separation (Bramlett & Mosher, 2002). The vast majority of these people are probably deeply in love when they marry. Later, when something in the relationship changes, a series of events is set in motion that ends in the dissolution of the marriage. Could it be that many of these people entered into the marriage with unrealistic expectations about love that they acquired from romantic depictions of it in movies, books, and poems (Segrin & Nabi, 2002)? Could it be that because they did not understand what love really is, they failed to anticipate how it might change, and were disillusioned by the changes? Could be. Let us take a look at what the science of love has to say and find out.

What is Love?

Think seriously for a moment about what it means to be in love with someone. What kinds of feelings and behaviors are essential parts of romantic love? David Buss (1988) found that both males and females view commitment as a key aspect; he suggests that it is the most important component of love.

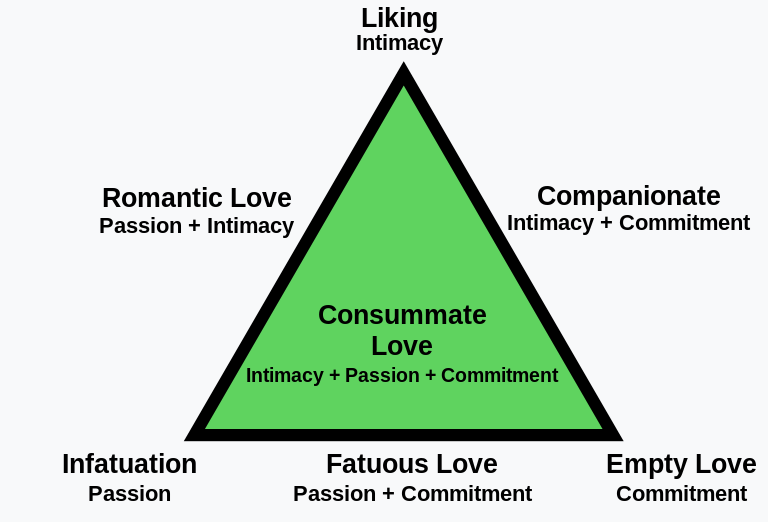

Robert Sternberg (1986), in his triangular theory of love, added passion and emotional intimacy to the mix. Intimacy is the emotional closeness that comes from sharing private thoughts. Passion is the desire for physical closeness; it is based on physical attraction, and it includes sexual desire. Each of these components can work together to represent different types of love (e.g., intimacy, romantic, companionate, passion, fatuous, commitment, and consummate. According to Sternberg, strong relationships are those for which the partners are similar in the levels of passion, intimacy, and commitment they feel toward each other (i.e., consummate love). Sternberg (1998) has also noted that individuals harbor their own personal expectations about how romantic love is supposed to be. Relationships that meet those expectations will be satisfying, and those that do not meet them will not be satisfying.

Ellen Berscheid and Elaine Hatfield (1978) have distinguished between two kinds of romantic love. Passionate love is common early in a relationship; it is marked by intense feelings and physical desire. Over time, passionate love often fades in a relationship, leaving companionate love. Notice that we did not say, “leaving only companionate love.” That would imply that companionate love is some lukewarm leftover feeling that lingers after the “real” love has faded. Companionate love is the stuff of commitment and emotional intimacy. Partners who feel companionate love essentially regard each other as best friends. Both types of love are related to happiness but in different ways. Passionate love is related to the presence of positive emotions, whereas companionate love is related to overall life satisfaction (Kim & Hatfield, 2004)

It looks as if romantic love is a universal human experience; researchers using a limited set of criteria found it in 90% of cultures surveyed throughout the world (Jankowiak & Fischer, 1992). There are, however, significant cultural differences in how romantic love is experienced. As you might guess, individualistic and collectivistic cultures differ on several important aspects of love. For example, people from collectivistic cultures tend to value and experience the companionate aspects of love more than people from individualistic cultures, who experience more passion and place more emphasis on personal fulfillment in love relationships (Dion & Dion, 1993; Gao, 2001). In many collectivistic cultures, marriages are arranged and passion is not expected. Instead, couples are expected to develop companionate love over time (Epstein et al., 2013; Levine et al., 1995).

passionate love: love that is marked by intense feelings and physical desire

companionate love: love that is marked by high levels of commitment and emotional intimacy

triangular theory of love: Robert Sternberg’s theory that love involves passion, commitment, and emotional intimacy

Why Do People Fall in Love?

The exact reasons why any two people fall in love are still a mystery. Psychologists have been able to figure out many of the important factors that can lead to love, however. We will mention three of them; the first two you might be able to guess, but we may surprise you with the third.

What first draws you to a potential romantic partner? It is not necessarily true in all cases, but the initial attraction between two people is often physical. And although there is some truth to the common belief that “beauty is in the eye of the beholder,” people tend to agree very well about the physical attractiveness of individuals, regardless of the ethnic and racial groups of rater and rated person (Cunningham, et al. 1995). For example, faces that are symmetrical—that is, the left side is close to a mirror image of the right side—are judged attractive throughout the world, as are faces that do not have extreme features (Jones et al., 2003; Mealey et al., 1999; Rhodes et al., 2002). Some combinations of physical features are very frequently found attractive. For example, females with large, widely spaced eyes and a small nose are judged attractive (Cunningham, 1986). Other features are more dependent on culture. For example, whites rate the attractiveness of heavy females lower than African Americans do (Hebl & Hetherton, 1998; Jackson & McGill, 1996).

Once you discover that you are physically attracted to someone, your next step is to talk to that person. What discovery about the other person is most likely to increase your attraction? Perhaps the biggest factor is the degree to which the other person is similar to you. When you speak to the person, the more they agree with you—on politics, music, sports, television shows, favorite color, whether you are a dog person or a cat person—the more you will like them (Byrne & Nelson, 1965). In short, the common idea that “opposites attract” is nearly entirely a myth. Similarity even extends to physical attractiveness. People very typically wind up with a partner who is close to them in physical attractiveness (Berscheid et al., 1971). Keep in mind that similarity levels in physical attractiveness do not always equate to higher levels of relationship satisfaction (Hunt et al., 2015).

Many people believe that each individual has one true soul-mate, his or her perfect match. If this were true, your soul-mate would probably live in Asia, where well over half of the world’s population resides. Instead, out of the 7.8 billion people on the planet, there are likely thousands, if not millions of potential partners who would make excellent matches for an individual. In reality, most people fall in love with someone who is close to them, someone they met at work or school, for example (Michael et al., 1994). It is not simply that having someone nearby magically attracts you to him or her. Rather, proximity affords the opportunity for frequent contact, and that is what makes you like the other person. This effect, called mere exposure, was discovered by Robert Zajonc (1968), and it is one of the most well-known effects in psychology. It has been demonstrated many times, with many different stimuli, such as pictures, sounds, and characters from an unfamiliar alphabet. It also works with people. For example, in one study, the researchers varied the number of times (0, 5, 10 or 15 times) that four female research assistants attended a class during the semester. At the end of the semester, the asked students how much they liked each assistant. The more times the assistant had attended, the more the students liked her (Moreland & Beach, 1992). We confess, this is the least magical reason for falling in love, but in a way, it is the most intriguing. Think about it. Your affection for someone increases simply because you come in contact with the person a number of times.

Human Sexual Behavior

By now, you may have noticed that throughout this book, we have been illustrating concepts with thinly disguised examples from our own lives, friends and families. We will not be doing that in this section.

We are simultaneously attracted to sex and shielded from it. It is mysterious and alluring, yet forbidden and shocking. That is how we can have a situation like the 2004 Super Bowl halftime show, during which two entertainers shocked hundreds of millions of people with a sexual display that may or may not have been choreographed. When Justin Timberlake grabbed at Janet Jackson’s costume, her breast was exposed on live TV. This “wardrobe malfunction” led people to express outrage at such an indecent act and launched a Federal Communications Commission investigation. Yet, the exposure was the single most frequently replayed moment ever recorded by TiVo, a precursor appliance to the DVR that allowed viewers to pause and replay live TV, and it was the most sought item ever reported from an earlier internet search engine Lycos.

Misconceptions about sex

In light of our culture’s contradictory feelings about sexual behavior, many people’s interest in sex ends up being indulged secretly. It is, after all, an intensely private act. People’s discomfort with admitting to an interest in sex and asking open questions about it leads to a great deal of misinformation. In the case of romantic love, misinformation may contribute to the high rate of marital discord and divorce. In the case of sex, ignorance and misinformation is even more serious; it contributes to sexually transmitted diseases or infections, unwanted pregnancy, and even distorted attitudes that can lead to sexual violence.

To give you an idea of what we are talking about, let us address a few commonly held misconceptions about sex in the US. Keep in mind that this is by no means intended to be an exhaustive list.

- Misconceptions about sex education. Many people believe that sex education leads to sexual behavior and that abstinence-only sexual education is the most (or only) effective way to reduce early sexual activity and teen pregnancy. As you might suspect, this has been a heavily researched topic, but because some of the research in this area is conducted by people who have a strong interest in the outcome, some of that research is problematic. A recent review of reviews has drawn some solid conclusions, however. The researchers identified 37 review articles containing 224 individual studies (all randomized controlled trials, the best design for drawing causal conclusions). The overall conclusions were that although abstinence-only education generally increases knowledge about the risks of sexual behavior, it does not lead to positive changes in adolescents’ actual behavior. In contrast, comprehensive education generally improves knowledge, attitudes, and behavior (Denford et al. 2017). The results are not extraordinary, though. There are some studies that found no effect, and even a few that found that the education increased sexual behavior. Part of the problem is that there are a great many variations in what the education includes, and several different behaviors that might be affected.

- Misconceptions about condoms. Many people believe that condoms have a very high failure rate. In reality, if condoms are used correctly, they have a failure rate of 3%. Unfortunately, however, another set of misconceptions concerns the correct usage of a condom. Between one-third and one-half of adolescents in the US have incorrect beliefs about condom usage that can lead to their failure ( Brown et al., 2008; Crosby & Yarber, 2001).

- Misconceptions about rape. Among the myths about rape are these: females commonly lie about being raped, only sexually promiscuous females are raped, and many females secretly enjoy the thought of being raped. A great deal of research has examined these rape myths and discovered that they can be quite harmful. First, you will not be surprised to learn that males are much more likely than females to believe rape myths (Ashton, 1982; Fonow et al., 1992: Hockett et al., 2015). People who believe rape myths are less likely to judge that a scenario meeting the legal definition of rape is actually rape; they assign less blame to a rapist and more blame to the victim than other people assign; they assign shorter sentences to male convicted of rape in “mock trial” research; they score higher on surveys that measure hostility toward females; they have more negative attitudes toward rape survivors; and they are more accepting of interpersonal violence (Lonsway & Fitzgerald, 1994). More dramatically, males who believe rape myths are more likely to admit that they might force a woman to have sex with them (Hamilton & Yee, 1990; Reilly et al., 1992). After this list, we are sure it will come as no surprise that males who believe the myths are also more likely to commit acts of sexual aggression, measured by self-report and by the actual commission of criminal sexual aggression (Murphy, Coleman & Haynes, 1986; Fromuth et al., 1991).

Sex throughout life

There is a wide range in media portrayals of adolescent sexual behavior. In reality, it can be difficult to gauge adolescents’ sexual behavior because people hold different opinions about what constitutes “having sex.” For example, one survey indicated that 59% of college students did not consider oral-genital contact to be “having sex” (Sanders & Reinisch, 1999). Not surprisingly, rates of oral-genital contact are still fairly high among young adults with many engaging in these activities without using safer sex practices (Holway & Hernandez, 2017). This furthers the point that young adults may not view oral-genital contact as sex and thus do not perceive it as an activity that has many risks.

Many parents have been concerned about early sexual activity in their children through the years. It is true that adolescents had sexual intercourse at earlier ages throughout most of the 20th century. The trend peaked in the early 1990s and began to reverse, however. For example, in 1990, 54% of high school students reported that they had ever had sex. By 2002, it had dropped to 46% of 15 – 19 year-olds. From there, it fell lower, especially for males. In 2015 – 2017, 42% of 15 – 19-year-old females and 38% of 15 – 19-year-old males reported that they had ever had sexual intercourse (Martinez & Abma, 2020).

In part because of a lack of consistent and correct information about sex and sexuality, adolescents are in particular danger of contracting sexually transmitted diseases/infections. According to the US Centers for Disease Control, teenagers and young adults ages 15-24 have about half of the sexually transmitted diseases in the US, despite being only one-quarter of the sexually active population (CDC, 2017; Sherman, 2004).

Sexual activity peaks in the adult years, during the early years of marriage. Contrary to many people’s beliefs and the countless “married equals no sex” jokes, married couples have more frequent sex than singles (Twenge et al., 2017). For example, in one of the most comprehensive national surveys on sexual behavior ever conducted in the US, 19% of single males versus 36% of married males and 13% of single females versus 32% of married females reported having sexual activity 2 to 3 times per week (Lauman et al. 1994). There is a gradual decline in married couples’ frequency of sex as they age, from 2.2 times per week in their 20’s to 1.3 times per week in their 40’s, to 0.6 times per week in their 60’s and 0.3 times per week in their 70’s (Smith, 1994). By the way, if you are tempted to compare yourself to these averages, do not do it. There is huge variability; a better gauge is your and your partner’s personal satisfaction with your sex life.

Biological and psychological influences on sexual behavior

As you may recall from Unit 3, evolutionary psychology has a great deal to say about human sexual behavior. As it turns out, evolutionary psychology’s explanations of male and female mating behavior are among its most provocative and controversial contributions to the field. As the evolutionary thinking goes, the specific selection pressures faced by a species leads to the adoption of, or preference for, different reproductive strategies. Because males and females throughout our evolutionary history have frequently faced different selection pressures, the two sexes have somewhat different preferences.

A basic distinction is between long-term and short-term mating strategies. A long-term mating strategy denotes a set of behaviors that promote sex only within a long-term, committed, monogamous relationship. A short-term strategy essentially means casual sex with multiple partners.

Both males and females can and do use both, but situations throughout evolutionary history have suggested some important differences related to their use. Specifically, pregnancy involves a much higher biological investment for females than males. Males produce millions of sperm per day, whereas females have about 400 ova in their entire lives, so right from the start, the conception of a single child represents a much higher proportion of a woman’s lifetime reproductive capacity. In addition, between pregnancy, birth, and breastfeeding, a woman is unable to conceive for a period that can reach 4 years or more for each child. Biologically speaking, the man is done nine months before the birth of the child. The only time that he is unable to conceive again is during the refractory period that occurs after ejaculation, which can be as short as a few minutes (see the section below). The overall result is an enormous biological investment in a child by a female and a very small biological investment by a male. Because of the large differences in parental investment required by males and females in the case of a pregnancy, one would expect females to be more selective in mate choices, even when engaging in a short-term encounter. And this is indeed what researchers have found (Buss & Schmitt, 2011). For example, men are far more likely to agree to have sex with a stranger than women are. In one dramatic demonstration of this, a member of the opposite sex approaches a target participant and says, “I have been noticing you all day, and I find you very attractive. Will you have sex with me?” In one version of this study, 75% of college-aged men said yes, and 0% of women did (Clark & Hatfield, 1989). Similarly, in a survey across 52 different countries, men were found to consistently desire more sexual partners than women do (Schmitt, 2003).

Evolutionary psychologists point out that when men and women are engaging in long-term mating strategies, their preferences are more similar, but that the differences in parental investment lead to some lingering differences between males and females. Although we are simplifying a bit, ancient males were more successful biologically if they chose mates who could conceive and give birth, so they evolved more of a preference for females whose appearance signaled that they were fertile and healthy, such as youthful appearance, smooth skin, and a specific ratio of the size of the waist compared to hips. Because these physical cues to fertility are so important, evolutionary psychology predicts that males will place a great deal of value on physical appearance and age when choosing mates. Females, on the other hand, were more successful biologically if the few children that they did bear survived. Thus, they evolved a preference for males that could help them do that. In other words, ancient females preferred males who signaled that they could be good providers for their children. These cues to a man’s ability to provide include high social status, ambition, dependability, willingness to commit, and athletic ability (Buss, 2003).

Evolutionary psychologists have conducted very ambitious research projects to test many of these claims about mate preferences. Of course, the claims cannot be tested directly because no one knows for sure what the specific evolutionary pressures were in ancient times. Instead, the reasoning is that if the evolutionary explanations are correct, then the predicted mate preferences should be seen throughout the world, regardless of culture. In one early study, researchers conducted surveys of people aged 14 to 70 in 37 different cultures around the world, over 10,000 people total, and found strong support for the predictions of evolutionary psychology. For example, in all 37 cultures, they found that men judged the physical attractiveness of a mate more important than women did—although both genders judge it important (Buss & Schmitt, 1993). Similarly, in all 37 cultures, women judged the social status of a mate more important than men did (Buss et al., 1990).

As impressive as these results are, they are not the last word on the issue. Alice Eagly and Wendy Wood (1999; Wood & Eagly, 2012) argued that the gender roles that have developed in a specific culture can have a large impact on mate preferences. Suppose in a particular culture men are expected to work outside the home and provide material support for the family while women are expected to stay at home and care for the children. In this case, you would expect men to select women who appear to be good at fulfilling their expected role, and vice versa. Indeed, all of the cultures in the Buss et al. research have gender role expectations just like these, although the role expectations are stronger in some cultures than in others (that is, some cultures have very rigid gender roles, others are more lax). Eagly and Wood reanalyzed the Buss et al. (1990) results and found that the cultures that have stronger gender role expectations have larger sex differences in mate preferences. Eagly and Wood have drawn the conclusion that gender role inequality in general can explain the existence of the gender difference in mate preferences. Thus, they have offered an alternative explanation of the Buss et al. results that does not rely on an evolutionary theory.

Now you may be wondering which view is correct: Do people choose mates because of preferences that have evolved throughout human history (the Buss et al. view) or because of their adaptations to gender role expectations in the current culture in which they live (the Eagly and Wood view)? Perhaps this is a false dichotomy (see Module 1). In other words, they could both be correct. Similar to the way the nature and nurture issue has played itself out in other contexts, evolutionary psychology can help us to understand the mechanism in nature by which gender differences exist at all. Then, the properties of individual cultures, such as gender inequality, can explain the nurture side of the equation, through which human behavior can stray from or intensify the predispositions that nature has put in place. More recent research has pursued this line. David Schmitt was involved in a survey of nearly 17,000 people from 53 nations (even more ambitious than the Buss research; one article based on this survey project listed 99 individual co-authors!) that supported this view. In another article that described the phenomenon of “mate poaching,” that is, trying to attract someone who is already in a relationship, Schmitt found evidence that supported the impact of evolution, social roles, and individual personality, another example of the complex interaction of nature and nurture (Schmitt, 2004). Most recently, Walter et al. (2020) replicated a version of the multi-culture studies (this time with 45 different countries; 108 co-authors this time around!) and found solid support for the evolutionary psychology predictions of men having a stronger preference than women for attractive, young mates and women having a stronger preference than men for older mates with good financial resources. They also found some support for the gender role expectation side of the explanation as well, as gender equality predicted the actual age of participants’ partners.

Sexual response cycle

Another way to think about the biology of sex is to consider what happens during the sexual act itself. According to Masters and Johnson (1966) the sexual response cycle is similar in men and women. There are four phases: excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution. During excitement, the genitals become aroused; the penis becomes erect and the vagina becomes lubricated. In women, the tip of the clitoris swells, the upper portion of the vagina expands, and nipples become erect (as they do in some men, too). During plateau, breathing rate, pulse rate, and blood pressure increase. In men, the tip of the penis swells, and a small amount of fluid (not semen) appears. In women, the outer portion of the vagina contracts and the clitoris is retracted. During orgasm, the genitals contract rhythmically, as do many muscles throughout the body. Breathing rate, pulse rate, and blood pressure are at their highest during orgasm. The pleasurable feeling that both men and women experience is actually quite similar, contrary to what many people think. Vance and Wagner (1976) had men and women write out descriptions of how orgasms felt. A panel that included gynecologists, medical students, and clinical psychologists could not tell the difference between men’s and women’s descriptions. The final phase is resolution, during which the bodies return to normal. After orgasm, men have a refractory period, during which they cannot have another erection or orgasm. The period can last for a few minutes in some men, up to a full day in others; the refractory period tends to grow longer as men age. Women do not have a refractory period, so they are able to have multiple orgasms if they are stimulated again.

excitement: phase of sexual response when genitals become aroused

plateau: phase of sexual response before orgasm, when breathing, pulse rate and blood pressure increase

orgasm: phase of sexual response during which genitals contract rhythmically

resolution: phase of sexual response during which the body returns to normal

refractory period: period of time after orgasm in men during which they cannot have another erection or orgasm

At one level, sexual response is a simple reflex between neural centers in the spinal cord and the sex organs. In men, the spinal cord receives input from stimulation of the penis (or nearby areas), which then sends neural signals through the parasympathetic nervous system—the part of the autonomic nervous system that generally calms the body—to produce an erection (McKenna, 2000). The erection itself results when muscles that surround the arteries in the penis relax, allowing the arteries to fill with blood. With continued stimulation of the penis, the spinal cord sends a message via the sympathetic nervous system (the arousing part of the autonomic nervous system), which begins muscular contractions that control ejaculation, the expulsion of semen from the penis. In women, the clitoris and vagina participate in sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system reflexes, but the exact mechanisms by which they work are not as well understood (Hyde & DeLamater, 2003).

For both men and women, sexual response is far more than these simple reflexes. For example, tactile stimulation of the penis while a man is washing in the shower usually does not produce an erection, whereas the gentlest touch during the opening moments of a sexual encounter often does. In fact, you may realize that both men and women can enter the excitement phase of sexual response without any physical stimulation at all. Obviously, the brain is involved in sexual response. An individual’s cognition and perception are essential features of sexual arousal (Walen & Roth, 1987). Brain areas that are important for cognition, sensation, and perception, then, such as the thalamus and certain areas of the cortex, are active during sexual behavior. Another area of the brain that appears important for sexual behavior is the limbic system, the set of brain structures that form a ring around the thalamus and are important for emotions in general. Research in which electrodes were used to electrically stimulate the limbic system of monkeys and rats, and fMRI research on humans have both found support for the role of specific limbic structures such as the hypothalamus and the cingulate cortex, usually considered part of the limbic system although it is part of the cortex (Paredes & Baum, 1997; Park et al., 2001; Van Dis & Larsson, 1971).

Hormones are also involved in sexual arousal and behavior, although they are involved far less dramatically than people believe. If you remove all testosterone from the body of a male by castration (as has been done on occasion to violent sex offenders), they will very likely lose interest in sexual behavior—but not immediately and not always completely (Carter, 1992). On the other hand, if a male already has sufficient testosterone, giving them more will probably not increase their sex drive. There is a relationship between the amount of testosterone in the bloodstream and sexual activity in adolescent males, but no solid relationships have been demonstrated in healthy adult men (Sherwin, 1988; Udry et al., 1985). Testosterone is also related to sexual behavior in females perhaps more strongly than in males. Researchers have found correlations between sexual motivation and levels of testosterone in healthy adult females (Morris et al., 1987). It is important to remember that in both males and females once the level of hormones reaches a minimum threshold, changes in the level have a relatively small effect (or no effect) on further sexual behavior.

Debrief

- What is your opinion about the mate selection ideas of evolutionary psychologists?

- Why do you think our culture is so conflicted about sex and sexuality?

22.2 Sexual Orientation

Activate

- What, specifically, attracts you to another person romantically?

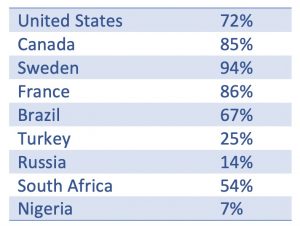

As you may realize, there has been a marked improvement in attitudes toward people with homosexual orientations recently. Some casual observers might even believe that the struggle for acceptance is over, but unfortunately, that is not quite true. Despite the significant movement in public opinion over the last ten years or so, the topic of sexual orientation is still controversial. Consider the results from 10 different countries in a worldwide survey conducted by the Pew Research Center:

Percentage who say that homosexuality should be accepted by society

Source: Pew Research Center 2020

So maybe in Sweden, the struggle is (almost) over. Many people, often for religious reasons, still do not accept gays or lesbians and believe that same-gender sexual behavior is wrong. Many also note that it is “unnatural,” as sex without the possibility of reproduction cannot be biologically useful. Well, one thing we can tell you is that, despite many unanswered questions, sexual orientation from psychologists’ perspective is far less controversial than it is in the general population. To be sure, there are still serious disagreements about what causes sexual orientation, but there is a growing agreement about several important aspects. If you have strong religious-based attitudes against homosexuality, we are unlikely to change your mind in this short section. You should know what the science of sexual orientation has to say, however. And we will return to the “it is unnatural” argument shortly.

Let us start with some definitions and clarifications. Sexual orientation refers to the gender to which an individual is sexually attracted and with which the individual is prone to fall in romantic love. Many people categorize sexual orientation into heterosexual and homosexual (or, to use more inclusive language, gay or straight), but that is really a false dichotomy (see Module 1). Why? Because there are more than two sexual orientations, of course. People who have a bisexual orientation are attracted to both genders, people with a heterosexual orientation are attracted to the opposite gender, and people with a homosexual orientation are attracted to the same gender. We will be adopting the term non-heterosexual orientation to refer to sexual orientations that are not heterosexual. Of course, you probably already knew that there are many different sexual orientations (asexuality, bisexuality, homosexuality, pansexuality, etc.). There is even the intriguing possibility that sexual orientation falls along a continuum, a position that has some scientific support (Savin-Williams, 2016). Note that sexual orientation is separate from one’s gender identity (Module 17), although there is some relationship, as we shall soon see.

Instead of focusing on understanding non-heterosexual orientations, many psychologists consider that their focus is to understand sexual orientation in general. This is not “political correctness,” as some may charge. The reason is that it looks like variations of the same basic mechanisms are responsible for heterosexual and non-heterosexual orientations. Reflect on your answers to the Activate question for this section. Many straight people are puzzled by the question and respond that they do not know why they are attracted to and fall and love with the opposite gender; they just are and they just do. It is the same with people who have a same-gender orientation. Despite this change in psychologists’ general focus, however, the practical focus still tends to be on understanding same-gender attraction.

How Common is Non-Heterosexual Orientation?

This has been a remarkably difficult question to answer. There are different ways to measure it (physiological, self-reports of behavior or attraction, self-reports of identification), the different measures and people’s orientations might not be stable over time, and people might be unwilling to admit to non-heterosexual orientations because of stigmas (Bailey et al., 2016). Let us use one representative fairly recent estimate to give us an idea of the numbers. Gates (2011) reviewed several individual estimates and concluded that about 3.5% of the US population identifies as gay, lesbian, or bisexual. Altogether, that corresponds to approximately 9 million LGBT (T for transgender) individuals in the US, which is near the population of New Jersey. Nineteen million (8%) report engaging in same-sex sexual behavior, and 25.6 million (11%) report some same-sex sexual attraction. So, we may be talking about numbers around this range: 3.5% to 11% (or 9 to 25.6 million).

non-heterosexual orientation: sexual orientations that are not heterosexual

sexual orientation: gender to which an individual is sexually attracted and with which the individual is prone to fall in romantic love

What Causes Sexual Orientation?

Before describing some specific possible causes of sexual orientation, let us address the “it is unnatural argument” that some advance against non-heterosexuality. It turns out that this is a relatively easy argument to refute using the rules of deductive logic that we outlined in Module 7.

If p, then q;

p;

therefore q.

If something appears in nature, it is, by definition, natural (If p, then q)

Homosexual behavior, defined as genital interaction between animals of the same sex, appears in nature (in hundreds of species, see below) (p)

Therefore, homosexual behavior is natural (q)

Indeed same-sex genital interaction, sometimes to orgasm has been observed at least occasionally in hundreds of species, including bonobos, mountain gorillas, macaques, baboons, and dolphins.

As we turn to describe causes of sexual orientation in humans, it might be useful to start with an important statement from a comprehensive review of the science published in 2016: “No causal theory of sexual orientation has yet gained widespread support. The most scientifically plausible causal hypotheses are difficult to test.” (Bailey et al., 2016, p. 46). The reasons for this might be obvious to you. First, it is impossible to conduct experimental research in this area. Second, even longitudinal research can be a challenge, given the political difficulties that sometimes accompany research in this area, and the relatively low prevalence of non-heterosexual orientations. For example, a researcher would need to start out with 10,000 participants to follow over decades in order to have an adult sample of 350 people with a non-heterosexual orientation. And that is assuming that everyone remains in the study for the next 20 years (which never happens). Researchers are forced to do a lot of retrospective design studies, in which adults remember experiences and thoughts from their childhood, and prospective design studies, which are similar to longitudinal studies with one key difference. In a prospective study, participants are chosen at the outset because they are likely to be interesting subjects as time goes on. You probably noticed that there are key limitations to each of these study types: retrospective studies rely on imperfect human memory, and prospective studies have a selection bias.

Even with all of the difficulties, scientific support for what Bailey and his collaborators called non-social causes is much stronger than for social causes. One reason this is important is that people’s attitudes toward non-heterosexuality are strongly related to the types of causal explanations they believe. If they believe that non-heterosexual orientations result from social causes, such as early sexual experiences and societal acceptance, they tend to hold negative attitudes. On the other hand, people who believe in non-social causes such as genes and hormones tend to hold positive attitudes.

One of the strongest correlates of adult non-heterosexuality is consistent childhood gender nonconformity, when a child (as early as pre-school) behaves like the other gender. These behaviors can include: cross-dressing, playing with dolls, desire for girl playmates, not liking competitive sports, and wanting to be a girl in boys, and more-or-less the opposite in girls. Some of the most convincing research (to our eyes) showed videos of children who later grew up to be heterosexual or non-heterosexual to research participants, who were much better than chance at predicting who ended up with each orientation (Rieger et al., 2008). Gender nonconformity is also more common among adults with non-heterosexual orientations. Because these differences start so early and are seen in cultures throughout the world, it is not likely that the nonconforming behaviors are culturally learned (Bailey et al., 2016).

The non-social explanations consist largely of the role of hormones on development and genetics. First, let us talk about hormones. As you may recall, hormones play an important role in the development of a fetus. For example, developing testes produce androgens, which then lead the sex organs to become male sex organs. These circulating hormones also likely help determine brain differences that are related to adult sexual behavior. It is through this mechanism that heterosexual and non-heterosexual orientations might develop. Again, without being able to experimentally manipulate levels of androgens for a developing fetus, we are left to examine the hypothesis using indirect techniques. There are three parts to the evidence stream:

- Experimental and observational research in animals. For example, research in rodents has found that by manipulating levels of androgens early in development can cause males to exhibit female-typical sexual behavior and females exhibit male-typical behaviors (Henley et al., 2011).

- Consistent evidence through case studies in humans. Some humans are exposed to abnormal levels of androgens prenatally because of genetic conditions. For example, women who are exposed to higher levels of androgens before birth have higher rates of gender nonconformity (Berenbaum & Beltz, 2011).

- Evidence of other consistent effects of different levels of early hormones in humans. This might sound like the oddest piece of evidence but “finger-length ratio” studies are consistent with this early hormone exposure hypothesis. Compare the length of your index finger and ring finger on one hand. Females tend to have a larger ratio of index to ring finger than males do. But females who have been exposed to high levels of androgen prenatally have smaller ratios (more like males), and males who have conditions that make them insensitive to androgens have larger ratios (more like females) (Honekopp & Watson, 2010; Berenbaum et al., 2009). Although finger length ratio differences for non-heterosexual versus heterosexual individuals have only been consistently observed for females, this is still a contender for part of the explanation (Bailey at al., 2016).

Taken together, most researchers agree that exposure to androgens prenatally at least contributes to gender nonconformity, which then can play a significant role in adult sexual orientation (but no one thinks that this is the whole story).

Genetics clearly also plays a significant role in sexual orientation. Recall that behavior genetics research tries to identify differences in a trait in a population (in this case sexual orientation) that result from differences in genes and differences in the environment. A stable estimate of heritability takes years to develop because it requires several individual studies. Bailey et al. (2016) arrived at the best current estimate of 0.32 for the heritability of sexual orientation. This is a moderate level, with approximately one-third of sexual orientation variation appearing to be a result of genetic differences.

This means that there is a substantial role for environmental effects. But probably not the social environment. In other words, there is no high-quality evidence that social aspects, such as observational learning, other types of social contagion, parenting, or early sexual experiences influence sexual orientation. The studies that have examined these proposed links are plagued with various combinations of weak to null results, poor quality data and methods, and plausible alternative explanations for relationships that do appear (Bailey et al., 2016).

Rather, it is what we would call the non-social environment that appears important. One of the strongest pieces of evidence of the effects of this non-social environment is the fraternal birth order effect, in which having older brothers increases the likelihood that a male will have a same-gender orientation. This effect only occurs for biological older brothers with the same mother, not with adopted, step- or half-brothers, which would seem to rule out a social environment explanation. Just to be clear, we are saying that there is something in the mother’s uterus that changes when a developing fetus has had older brothers pass through that same uterus. One key possibility is the way the immune system of the mother responds to the earlier brothers, therefore changing the uterine environment for later developing males (Blanchard, 2001).

retrospective design: research study in which adults remember experiences and thoughts from their childhood

prospective design: research study that is similar to a longitudinal study in which participants are chosen before the study begins

gender nonconformity: when a person behaves or dresses like the societal expectations of another gender

fraternal birth order effect: theory that having older brothers increases the likelihood that a male will have a same-gender orientation

How is Sexual Orientation Discovered?

A key issue about having a non-heterosexual identity is that many people are afraid to admit it. It is still quite socially acceptable in many quarters to insult a gay person openly, and the US Supreme Court only deemed discrimination against LGBTQ+ individuals in employment unacceptable in 2020.

The culture of secrecy, shame, and discrimination contribute to the still problematic issue of violence against lesbians and gay men. The Federal Bureau of Investigation reported that hate crimes—crimes principally motivated by bias about the race, religion, ethnicity, gender, disability, or sexual orientation of the victim—based on sexual orientation was 1,303 in 2017 and 1,196 in 2018. With many of these crimes being underreported as hate crimes, scholars believe that these numbers may be higher.

Sexual orientation is pretty well set before adolescence (Weinberg & Hammersmith, 1981). The first challenge for the adolescent is to discover what their orientation is. This would seem a relatively straightforward process of simply noticing whether you are sexually attracted to men or women. Two factors make this discovery process more difficult. First, remember, there are at least a minimum of 3 orientations and a very real possibility that sexual orientation is on a continuum. It can be difficult to fit oneself into a box that has two compartments when the reality is far more continuous and complex. Second, because our culture is overwhelmingly heterosexual and correspondingly still somewhat disapproving of non-heterosexual orientations, adolescents do not approach this period in an unbiased way. Rather, they operate under the assumption that they are straight, and they tend to hold on to that belief for as long as they can. They may deny their orientation to themselves, or be confused about it, and only in time, come to accept it (Cass, 1979). Despite the barriers in the way of gay, lesbian, bisexual, and other people with non-heterosexual orientations developing healthy identities, most do seem to succeed. For example, they are as well adjusted as the general population (Ross et al. 1988).

Even after accepting their own sexual orientation, individuals will need to decide how open they will be about it to other people. Can they tell their parents, friends, acquaintances, and employers? Being openly gay can lead to hate crimes, social rejection and disapproval, and until very recently (June 2020) discrimination on the job (Corrigan & Matthews, 2003; Ragins & Cornwell, 2001).

Debrief

- Do you have any friends who are gay? Can you see how the ideas from the stereotype, prejudice, and discrimination discussion (Module 22) apply to sexual orientation?

- What do you think some of the “missing” environmental influences of sexual orientation are?

22.3 Marriage and Divorce

Activate

- If you are not yet married, do you expect to marry someday? If you do expect to marry, or already are married, how likely do you think your marriage is to end in divorce?

- Think about some happily and some not-so-happily married couples that you know fairly well. If you do not know enough married couples, you can use any couples who are in a serious, long-term, exclusive romantic relationship, as long as you end up with some couples who seem happy together and others not so.

- What are the important differences you can see between the two types?

- Which differences do you think might be the causes of happiness or discord, and which do you think might be the effects?

News reports in the US during the first half of 2004 were strident: the institution of marriage is under attack. Observers were referring to the decisions in San Francisco and Massachusetts to allow same-sex couples to marry. Now, there is little doubt that the institution of marriage is in decline, but it has nothing to do with same-sex marriage. Demographic changes in the US in the latter half of the 20thcentury led to sharply increasing numbers of divorced and never-married people. The percentage of households headed by a married couple declined from 71% in 1970 to 53% in 2000 (US Census Report, 2001). The decline is largely a result of people marrying later and divorcing more. Despite the large decline, the majority of US adults do find themselves in a long-term monogamous relationship for a large portion of their adult lives. Among all people over age 15 in the US, 27% have never been married, and fewer than 10% of people over 45 have never been married (US Census Report, 2003).

There are real physical and psychological benefits to being married. People who are married tend to have better physical health and psychological well-being than other adults (House et al., 1988; Kim & McKenry, 2002; Lee et al., 1991; Mookherjee, 1997; Murphy et al., 1997). Longitudinal research in many cases has led most observers to conclude that there is something about marriage that leads to positive outcomes, as opposed to good physical or mental health causing people to get and stay married (although this relationship is surely part of the picture).

However, not all marriage is good. Destructive marital conflict is related to many physical and psychological problems, such as depression, alcoholism, cancer, and heart disease (Beach et al., 1998; Fincham & Beach, 1999). It is also related to the poor adjustment of children, similar to the well-known negative effects of divorce (Grych & Fincham, 1990; Owen & Cox, 1997).

There is no lack of advice for people in search of marriage advice. A search on Amazon.com for “self-help marriage” returned over 30,000 results in June 2020. However, this abundance of advice is not all worthwhile. John Norcross and colleagues (2003) have undertaken a gargantuan effort to help us wade through the immense number of self-help resources that are on the market. They have conducted a series of surveys of almost 3,500 clinical and counseling psychologists in the US in order to determine the quality of thousands of self-help resources that are available to the general public. In the category of marriage, John Gottman’s books were clear favorites (Gottman, 1994; Gottman & Silver, 2000).

Gottman is not simply the author of the self-help books. He has conducted a great deal of research himself, which has appeared in the scientific literature throughout the years. Through his research, Gottman has discovered many key factors that seem to lead to marital satisfaction, dissatisfaction, and stability. The rest of this section summarizes some of them.

What Causes Marriages to Disintegrate

Many people have heard the famous statistic that the divorce rate in the US is 50%. This is a misinterpretation of the fact that for every two marriages in a single year, there is one divorce. These are not necessarily the same people marrying and divorcing. It is a safer conclusion to predict that someone’s lifetime risk of divorce is around 40% (Glick, 1988). Half of the divorces occur in the first 7 years of marriage (Cherlin, 1982; cited in Gottman & Levenson, 2002). One way that researchers estimate the divorce rate is to measure the number of divorces in a given year for every 1000 married women. According to this measure, the divorce rate in the US hit a 40-year low in 2018, with 15.7 divorces per 1000 married women (Allred, 2019). Gottman is convinced that the divorce rate could be even lower.

It can be quite difficult to determine the causes of marital discord, particularly if we try to do it simply by observing high-functioning and low-functioning marriages. For example, a marriage may sour because the partners frequently criticize each other, or the partners may frequently criticize each other because they have a poor marriage. As is so often the case when we are interested in real-world social and emotional questions, we are faced with a correlation, which does not point clearly to causes and effects. One way to help us determine which factor is the cause and which is the effect, however, is to use a longitudinal research design. If we can determine that a factor comes into play long before a couple is unhappy in their marriage, it gives us some confidence that the factor is a cause. Gottman and his colleagues were able to do just this. By observing newlyweds while they discussed an ongoing conflict, they were able to predict which couples would eventually divorce with 91% accuracy.

Although you could probably predict some of what Gottman and his colleagues found in their research, there were certainly a few surprises. First, contrary to popular opinion (and the advice given in some self-help books), anger in a marriage does not predict divorce because, in essence, everyone gets angry. Rather, it looks as if a particular kind of anger, or a particular way of expressing anger, is destructive. Specifically, when couples filled their conflict discussions with high-intensity negativity—criticism, defensiveness, contempt, listener withdrawal, and belligerence—they were much more likely to divorce (Gottman, 1994; Gottman et al., 2002). You don’t even need to be an expert to recognize some of the warning signs, if you know what to look for. In one study, college students were able to predict divorce with 85% accuracy by identifying hostility in husbands, sadness in wives, and lack of empathy in both partners (Waldinger et al., 2004).

Second, Gottman’s team found that one of the most common strategies recommended by marriage counselors was unrelated to the likelihood of divorce. Active listening is a communication strategy in which the listener paraphrases what he or she hears without evaluating. It can be very effective at clearing up miscommunication and is a key component of many therapies. Marriage counselors in particular often teach active listening to their clients so that the couples can use it when they argue. Gottman and his colleagues concluded, however, that the strategy was unrelated to marital stability, not because it did not work, but because couples rarely used it. During a conflict, couples’ emotions are running too high to allow them to employ active listening.

Gottman’s research has dispelled several additional myths. Many people believe that common interests keep marriages strong, but the research did not support this idea. Also, many think that a sign of a strong marriage is when couples reciprocate good deeds with other good deeds. Quite the contrary, Gottman found that this “quid pro quo” is more common in bad marriages; and the flip side occurs, too (bad deeds are reciprocated with bad deeds). Finally, the research has shown that the belief that avoiding conflict is unhealthy (that you should “tell it like it is”) is wrong.

Something that probably will not surprise you is that different behaviors in each partner predicted divorce. When a spouse quickly changed the tone of discussion from neutral to negative—for example, by beginning a discussion of a sensitive topic such as money disagreements by criticizing their partner—the couple was more likely to divorce. On the other hand, spouses who would not let their partners influence them were more likely to divorce. Finally, a couple’s ability to maintain positive behaviors, such as smiling or using humor, while they were discussing conflicts was related to marriage stability. Gottman has called these sorts of strategies to de-escalate conflict repair attempts. He notes that nearly all couples use them, but they are successful in stable couples only.

active listening: a communication strategy in which the listener paraphrases what he or she hears without evaluating.

repair attempts: a couple’s attempts to maintain positive behaviors, such as smiling or using humor, while they were discussing conflicts.

How to Have a Successful Marriage

So far, nearly everything has been focused on what predicts divorce. This is an unfortunate side effect of the fact that when people seek help for their marriage, they are nearly always at risk for divorce; it becomes the main focus. There is, however, much positive to say. Although couples that are in trouble are the most likely to seek advice to strengthen their marriage, Gottman has noted that all couples can benefit from it. In fact, it is easier to adopt the strategies if the marriage is not yet in trouble. As John F. Kennedy famously said, “The time to repair the roof is when the sun is shining.”

So, while the sun is shining, you might pay attention to many of the characteristics that Gottman has discovered in successful marriages (of course, these will work when it is “raining,” too). Perhaps the most important basic idea is that the couple needs to work on friendship first—in other words, on their companionate love. A marriage in which the couple are close friends is not devoid of passion, by the way. Gottman has noted that these marriages are much more passionate than when the couple encourages passion through occasional romantic gestures. Instead, the couple should work on everyday gestures, such as paying attention and responding positively to comments. They should look for opportunities to create a life together, for example, through new family traditions and rituals. Passion flows more freely when each partner feels generally positive about each other, as they do when they are intimate friends. As part of strengthening their friendship, couples need to become very familiar with each others’ likes, dislikes, hopes, and fears. They must find and build on fondness and admiration; if the couple is already in trouble, they may need to find these aspects in memory. The partners need to continually remind themselves of the positives. Gottman has said that the encouragement of fondness and admiration is especially important for protecting against contempt (a feeling that you are better than someone else), which may be the most destructive emotion for a marriage.

Every day is filled with a great many opportunities to improve a couple’s relationship. Imagine a couple just relaxing together in their family room after dinner. The wife turns to the husband and says, “Hey, let’s go on a hike this weekend.” The husband is busy watching TikTok videos on his phone and does not even respond to the request. Obviously, this is not a great interaction, but let us analyze it a bit to discover what is going on. Many times throughout the day, romantic partners make bids for connection. In this case, the invitation to go on a hike is a bid to share an adventure together (Brittle, 2015). The husband has three options, and in this case, he took the worst of the three. First, he can turn toward the bid. In other words, he can respond positively, by accepting the invitation. Second, he can turn against the bid, by acknowledging it but rejecting it, perhaps offering an alternative. Although not ideal, turning against does at least keep the lines of communication open. The worst response is turning away, in essence not even noticing or acknowledging the bid. In Gottman’s research, he discovered that couples who stayed married turned toward each others’ bids for attention 86% of the time. Couples who divorced turned towards each others’ bids only 33% of the time (Navarra & Gottman, 2013). So there are two elements to the advice: first, recognize when a statement or request is actually a bid for emotional connection. Second, turn toward that bid as often as you can.

In the discussion about predictors of divorce, you learned what a couple should not do during a conflict situation. On the positive side, couples need to learn how to distinguish between solvable problems tied to a particular situation and perpetual problems that reflect an underlying conflict and are likely to recur throughout their married lives. You can often tell the difference by how painful the problem is to discuss. When a couple recognizes that a problem is unsolvable, they should not try to ignore it. Instead, they should develop skills for coping and try to get to the point where they can discuss the problem without experiencing great distress. They should acknowledge that neither spouse will win and avoid doing anything that will make the problem worse.

Finally, Gottman also has some specific advice for couples: Accept influence. He emphasizes that attitudes such as “I wear the pants in this family” are fast roads to marital problems. Even in marriages in which one partner is the “boss,” they need to honor and respect their partner; the goal is mutual respect.

Debrief

- Which of John Gottman’s principles seem the most useful to you?

- Do you recognize any of Gottman’s warning signs in a current or past relationship or even as general tendencies in your personality?