CHAPTER VI: A SUNNY NEW YEAR

OURS was a lonely house the winter after Father’s death. The first forty-nine days when “the soul hovers near the eaves” was not sad to me, for the constantly burning candles and curling incense of the shrine made me feel that Father was near. And, too, everyone was lovingly busy doing things in the name of the dear one; for to Buddhists, death is a journey, and during these seven weeks, Mother and Jiya hastened to fulfil neglected duties, to repay obligations of all kinds and to arrange family affairs so that, on the forty-ninth day, the soul, freed from world shackles, could go happily on its way to the Land of Rest.

But when the excitement of the busy days was over and, excepting at the time of daily service, the shrine was dark, then came loneliness. In a childish, literal way, I thought of Father as trudging along a pleasant road with many other pilgrims, all wearing the white robes covered with priestly writings, the pilgrim hats and straw sandals in which they were buried—and he was getting farther and farther from me every day.

As time passed on we settled back into the old ways, but it seemed that everybody and everything had changed. Jiya no longer hummed old folk-songs as he worked and Ishi’s cheerful voice had grown so lifeless that I did not care for fairy tales any more. Grandmother spent more time than ever polishing the brass furnishings of the shrine. Mother went about her various duties, calm and

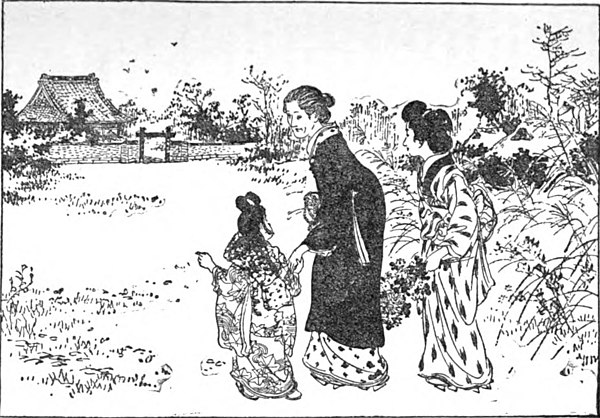

During these months, my greatest pleasure was going to the temple with Mother. Toshi, the maid, always walked behind, carrying flowers for the grave.

quiet as usual, but her smile was sad. Sister and I sewed and read together, but we no longer wasted time in giggling and eating sweets. And when in the evening we all gathered around the fire-box in Grandmother’s room, our conversation was sure to drift to mournful topics. Even in the servants’ hall, though talking and laughter still mingled with the sounds of spinning and grinding of rice, the spirit of merriment was gone.

During these months my greatest pleasure was going to the temple with Mother or Ishi. Mother’s special maid, Toshi, always walked behind, carrying flowers for the graves. We went first to the temple to bow our respects to the priest, my much-honoured teacher. He served us tea and cakes and then went with us to the graves, a boy priest going along to carry a whitewood bucket of water with a slender bamboo dipper floating on the top. We made bows to the graves and then, in respect to the dead, poured water from the little dipper over the base of the tall gray stones. So loyal to the past are the people of Nagaoka that, many years after my father’s death, I heard my mother say that she had never visited his grave when she had not found it moist with “memory-pourings” of friends and old retainers.

On February 15th, the “Enter into Peace” celebration of Buddha’s death, I went to the temple with Toshi, carrying as a gift to the priest a lacquer box of little dumplings. They were made in the shapes of all the animals in the world, to represent the mourners at Buddha’s death-bed, where all living creatures were present except the cat. The good old priest, after expressing his thanks, took a pair of chopsticks and, lifting several of the dumplings on to a plate, placed it for a few minutes in front of the shrine, before putting it away for his luncheon. That day he told me with deep feeling that he must say farewell, since he was soon to go away from Chokoji for ever. I could not understand, then, why he should leave the temple where he had been so long and which he so dearly loved; but afterward I learned that, devout and faithful though he was to all the temple forms, his brain had advanced beyond his faith, and he had joined the “Army of the Few” who choose poverty and scorn for the sake of what they believe to be the truth.

One evening, after a heavy snowfall, Grandmother and I were sitting cozily together by the fire-box in her room. I was making a hemp-thread ball for a mosquito net that was to be woven as part of my sister’s wedding dowry, and Grandmother was showing me how to put my fingers deftly through the fuzzy hemp.

“Honourable Grandmother,” I exclaimed, suddenly recalling something I wanted to say, “I forgot to tell you that we are going to have a snow-fight at school tomorrow. Hana San is chosen to be leader on one side and I on the other. We are to——”

I was so interested that again I lost my thread and it matted. I gave it a quick jerk and at once found myself in sad trouble.

“Wait!” said Grandmother, reaching out to help me. “You should sing ‘The Hemp-Winding Song.’ ” As she straightened my tangled thread, her quavery old voice sang:

“Watch your hand as it winds hemp thread;

If it mats, with patience wait;

For a thoughtless move or a hasty pull

Makes smaller tangles great.”

“Don’t forget again!” she added, handing back the untangled bunch of hemp.

“I was thinking about the snow-fight,” I said apologetically.

Grandmother looked disapproving. “Etsu-bo,” she said, “your eldest sister, before she was married, made enough hemp thread for both the mosquito nets for her destined home. You have now entered your eleventh year and should aim to be more maiden-like in your tastes.”

“Yes, Honourable Grandmother,” I replied, feeling with humiliation how true her words were. “This winter I will wind plenty of hemp thread. I will make many balls, so Ishi can weave the two nets for Sister’s dowry before New Year’s.”

“There is no need for such haste,” Grandmother replied, smiling at my eagerness, but speaking gravely. “Our days of sorrow must not influence your sister’s fate. Her marriage has been postponed until the good-luck season when the ricefields bow with their burden.”

I had noticed that fewer shop men had been coming to the house, and I had missed the frequent visits of tall Mr. Nagai and his brisk, talkative little wife, the go-between couple for my sister. So that was what it meant! Our unknown bridegroom would have to wait until autumn for his bride. Sister did not care. There were plenty of things to be interested in and we both soon forgot all about the delayed wedding in our preparations for the approaching New Year.

The first seven days of the first month were the important holidays of the Japanese year. Men in pleated skirts and crest coats made greeting calls on the families of their friends, where they were received by hostesses in ceremonious garments who entertained them with most elaborate and especial New Year dishes; little boys held exciting battles in the sky with wonderful painted kites having knives fastened to their pulling cords; girls in new sashes tossed gay, feathery shuttlecocks back and forth or played poem cards with their brothers and brothers’ friends, in the only social gatherings of the year where boys and girls met together. Even babies had a part in this holiday time, for each wee one had another birthday on New Year’s Day—thus suddenly being ushered into its second year before the first had scarcely begun.

Our family festivities that year were few; but our sorrow was not allowed to darken too much the atmosphere of New Year, and for the first time since Father’s death we heard sounds of merriment in the kitchen. With the hot smell of steaming rice and the “Ton-g—click! Ton-g—click!” of mochi-pounding were mingled the voices of Jiya and Ishi in the old song, “The Mouse in the House of Plenty,” which always accompanies the making of the oldest food of Japan—the rice-dough called mochi.

“We are the messengers of the Good-luck god,

The merry messengers.

We’re a hundred years old, yet never have heard

The fearful cry of cat;

For we’re the messengers of the Good-luck god,

The merry messengers.”

About two days before New Year, Ishi came into the kitchen looking for me. I was sitting on a mat with Taki, who was here to help for New Year time, and we were picking out round beans from a pile in a low, flat basket. They were the “stones of health” with which the demons of evil were to be pelted and chased away on New Year’s Eve. Jiya, in ceremonious dress, would scatter them through the house, closely followed by Taki, Ishi, and Toshi, with Sister and Etsu-bo running after, all vigorously sweeping, pushing, tossing, and throwing; and while the rolling beans went flying across the porches into the garden or on to the walks, our high-pitched voices would merrily sing, over and over:

“Good luck within!

Evil, go out! Out!”

Ishi had some errands to do and Mother had said that I might go with her to see the gay sights. How well remember that wonderful sunshiny winter day! We crossed the streets on paths cut between walls of frozen snow only three feet deep; for we had but little early snow that winter, and no tunnels were made until after New Year. The sidewalk panels were down in some places, just like summer time, and the shops seemed very light with the sky showing. On each side of every doorway stood a pine tree, and stretched above was a Shinto rope with its ragged tufts and dangling zig-zag papers. Most of the shops on that street were small, with open fronts, and we could plainly see the sloping tiers of shelves laden with all the bright attractions of the season. In front of every shop was a crowd, many of the people having come from near-by villages, for the weather had been unusual, and Nagaoka had hopefully laid in a supply of New Year goods that would appeal to the simple taste of our country people.

To me, many of the sights, familiar though they were, had, in the novelty of their surroundings, the excitement and fascination of a play. At one place, when Ishi stopped to get something, I watched a group of ten- or twelve-year old boys, some with babies on their backs, clattering along on their high, rainy-day clogs. They stopped to buy a candy ball made of puffed rice and black sugar, which they broke, each taking a piece and not forgetting to stuff some scraps in the mouths of the babies that were awake. They were low-class children, of course, to eat on the street, but I could taste that delicious sweet myself, as my eyes followed them to the next shop, where they pushed and jostled themselves through a crowd toward a display of large kites painted with dragons and actors’ masks that would look truly fearful gazing down from the sky, In some places young girls were gathered about shops whose shelves held rows of wooden clogs with bright-coloured toe-thongs; or where, beneath low eaves, swung long straw cones stuck full of New Year hairpins, gay with pine leaves and plum blossoms. There were, of course, many shops which sold painted battledores and long split sticks holding rows of five or ten feathery shuttlecocks of all colours. The biggest crowds of all were in front of these shops, for nobody was too poor or too busy to play hana on New Year days.

That was a wonderful walk, and I’ve always been glad I took it, for it was the only time I remember of my childhood when we had sunshiny streets at New Year time.

Notwithstanding our quiet house, the first three days of the New Year Mother was pretty busy receiving calls from our men kinsfolk and family friends. They were entertained with every-vegetable soup, with miso-stuffed salmon, fried bean-curd, seaweed of a certain kind, and frozen gelatin. Mochi, as a matter of course, was in everything, for mochi meant “happy congratulations” and was indispensable to every house during New Year holidays. With the food was served a rice-wine called toso-sake, which was rarely used except on certain natal occasions and at New Year time. Toso means “fountain of youth,” and its significance is that with the new year, a new life begins.

The following days were more informal. Old retainers and old servants called to pay respect, and always on one day during the season Mother entertained all the servants of the house. They would gather in the large living room, dressed in their best clothes. Then little lacquer tables with our dishes laden with New Year dainties were brought in and the rice served by Sister and myself. Even Mother helped. There were Taki, Ishi, Toshi, and Kin, with Jiya and two menservants, and all behaved with great ceremony. Kin, who had a merry heart, would sometimes make fun for all by rather timidly imitating Mother’s stately manner. Mother always smiled with dignified good nature, but Sister and I had to quench our merriment, for we were endeavouring to emulate Kin and Toshi in our deep bows and respectful manners. It was all very formally informal and most delightful.

On these occasions, Mother sometimes invited a carpenter, an old man who was always treated in our family as a sort of minor retainer. In old Japan, a good carpenter included the profession of architect, designer, and interior decorator as well as of a worker in wood, and since this man was known in Nagaoka as “Master Goro Beam”—the complimentary title of an exceptionally clever and skilful master-carpenter—and, in addition, was the descendant of several generations of his name, he was much respected. I was very fond of Goro. He had won my heart by making for me a beautiful little doll-house with a ladder-like stairway. It was my heart’s pride during all the paper-doll years of my life. On the first New Year’s Day that Goro came after Father’s death, he seemed quiet and sad until Mother had served him toso-sake; then he brightened up and grew talkative. In the midst of the feast he suddenly paused and, lifting his toso-sake cup very respectfully to the level of his forehead, he bowed politely to Mother, who was sitting on her cushion just within the open doorway of the next room .

“Honourable Mistress,” he began, “when your gateway had the pine decoration the last time, and you graciously entertained me like this, my Honourable Master was here.”

“Yes, so he was,” Mother replied with a sad smile. “Things have changed, Goro.”

“Honourable Master ever possessed wit,” Goro went on. “No ill-health or ill-fortune could dull his brain or his tongue. It was in the midst of your gracious hospitality, Honourable Mistress, that Honourable Master entered the room and assured us all that we were received with agreeable welcome. I had composed a humble poem of the kind that calls for a reply to make it complete; and was so bold as to repeat it to Honourable Master with the request that he honour me with closing words. My poem, as suitable for a New Year greeting, was a wish for good luck, good health, and good will to this honourable mansion.

“The Seven—the Good-fortune gods—

Encircle this house with safely-locked hands;

And nothing can pass them by.

“Then Honourable Master”—and Goro deeply bowed—“with a wrinkle of fun on his lips, and a twinkle of fun in his eyes, replied as quickly as a flash of light:

“Alas! and alas! Then from this house

The god of Poverty can never escape;

But must always stay within.”

Goro enjoyed his joke-poem so much that Mother united her gentle smile with the gay laughter of his companions who were always ready to applaud any word spoken in praise of the master they had all loved and revered.

But bright-eyed Kin whispered to Ishi and Ishi smiled and nodded. Then Taki and Toshi caught some words and they, too, smiled. Not until afterward did I know that Kin’s whisper was:

“The gods of Poverty are sometimes kind.

They’ve locked their hands with the Good-luck gods

And prisoned joy within our gates.”

Thus lived the spirit of democracy in old Japan.