27 Module 27: Healthy Lifestyle

Module 27: A Healthy Lifestyle

Let’s speculate for a few minutes about what would be the most effective way to improve people’s health. For example, if the world community made it a priority to immunize all children, the impact would be amazing. Or perhaps the impact would be greater if we ensured clean drinking water throughout the world. One factor that people often do not think about is improving mental health. The fact is, improvement in traditional “physical” health would be dramatic if mental health were given the attention it deserves. For example, major depressive disorder is probably a contributing factor to at least heart disease and diabetes, among other diseases (Module 29).

At a personal level, there is much about health that is out of your control. Good or bad genes and exposure to dangerous or infectious substances in the environment all make quite significant contributions to whether we are sick or healthy. On the other hand, we can make a dramatic impact on our health by focusing on the factors that are under our control.

We are sure you have heard of the “mind-body” connection. It is not a New Age concept but rather a concept well grounded in the scientific principles about human physiology, behavior, and mental processes. Remember that the mind is simply the brain and that the brain controls the whole body.

There are at least two ways to think about this mind-body connection. The first is to consider the role of psychological stress in physical illness. If people would learn how to manage stress effectively, their physical health would improve. Managing stress may be the single most effective action that is under your control, in no small part because it will also improve other controllable disease risk factors, such as obesity, substance abuse, and sleep deprivation. The second way to think about the mind-body connection is to realize that a great deal of our behavior has a direct impact on our physical health. For example, the types and quantities of food that we eat and the amount of exercise we get are obviously key components of having a healthy life. Psychology has a great deal to offer to help us understand, predict, and control these important behaviors.

This module has four sections. Section 27.1 describes the causes and health consequences of stress, and section 27.2 offers some of the best strategies that research has identified to help us manage stress in our lives. Section 27.3 helps you to understand eating behavior in general, as well as the causes behind the epidemic of obesity that the US is currently experiencing. Section 27.4 offers advice from one of the leading experts on behavior change about how people can make lasting changes to improve their own health.

27.1. Understanding stress

27.2. Coping with stress

27.3. Understanding obesity and eating disorders

27.4. Promoting good health and habits

READING WITH A PURPOSE

Remember and Understand

By reading and studying Module 27, you should be able to remember and describe:

- Stress response: fast and slow response, fight-or-flight, tend-and-befriend (27.1)

- Long-term effects of stress (27.1)

- Kinds of stressors (27.1)

- Methods for coping with stress (27.2)

- Body Mass Index, obesity, and overweight (27.3)

- Biological and environmental influences on eating behavior (27.3)

- Eating disorders: anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa (27.3)

- Prochaska’s transtheoretical theory (27.4)

Apply

By reading and thinking about how the concepts in Module 27 apply to real life, you should be able to:

- Identify sources of stress in your life (27.1)

- Recognize fight-or-flight and tend-and-befriend responses in yourself or others (27.1)

- Identify the ways that you already cope with stress (27.2)

- Determine your own BMI and decide whether you are in the health range or not. Speculate about factors that may have influenced the number. (27.3)

Analyze, Evaluate, and Create

By reading and thinking about Module 27, participating in classroom activities, and completing out-of-class assignments, you should be able to:

- Describe examples of the way you think about some stressors that you could change to cope with stress (27.2)

- Identify environmental cues that sometimes lead you to eat more than you should (27.3)

- Identify the stage you are in from Prochaska’s transtheoretical theory for a problem behavior in your own life (27.4)

27.1. Understanding Stress

Activate

- What are the most important sources of stress in your life?

- How does stress affect you? What are the physical, cognitive, and emotional consequences for you?

If we may be so bold, we would like to suggest that you need to understand stress. By now it has a very bad reputation, as most people have heard that it contributes to physical illness. We fear that many people do not realize just how strong the evidence is, however. On the other hand, it is easy to forget that stress can be good, even necessary sometimes.

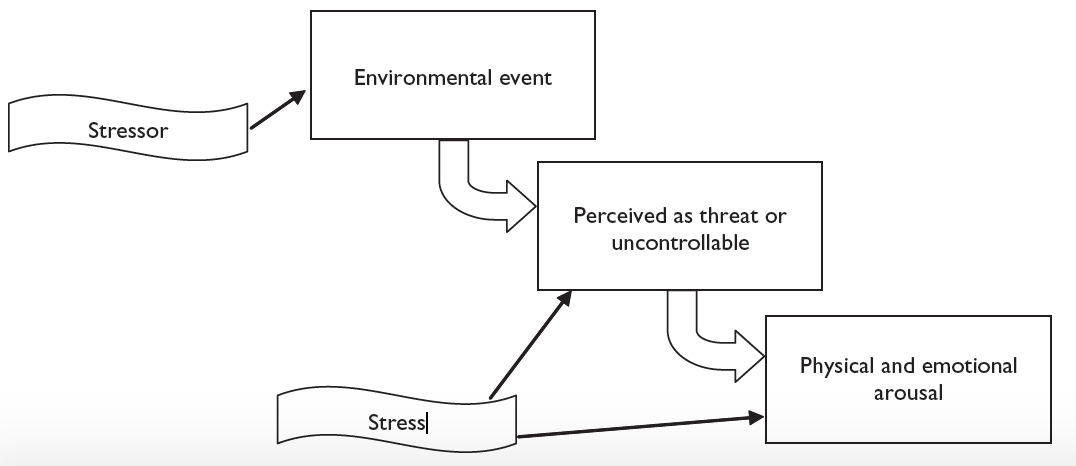

Let us start with a definition. Imagine a conversation with a friend who is complaining about her current situation. She tells you, “I have four exams over the next two days, I have to work until midnight, and my car is broken down. I am under a lot of stress.” When people use the word in everyday conversation, they tend to refer to the environment itself as the stress. For example, the exam is stress. For psychologists, however, the events or situations are stressors, and our response to those events is stress.

Making this distinction is not simply playing with words. It reveals a very important fact about stress, one that you can use to reduce stress in your own life. Quite simply, the very same event may lead to stress for one person and not for another. It is not the event itself that is the stress. Think of a situation like traffic. Many people hate traffic. After an hour on an expressway creeping along at 10 miles an hour, they are often tense, anxious, rushed, and angry. These individuals may be surprised to discover that some people like heavy traffic, however. They consider it one of the few chances during the day to be alone, with no family, work, or school responsibilities. They listen to music, a podcast, or an audio-book and relax. If the traffic-haters could figure out how to look at traffic the way some other people do, and not as a stressor, they could reduce their stress.

Certainly some general characteristics of events are likely to make them stressors. In short, events that are threatening and uncontrollable are stressful. Say you are confronted with a deadline for an important project at work or school. You can’t get out of it. Because of the project’s importance and the possibility of failure, you might find it threatening. That threat, combined with your lack of control over the deadline, is likely to make the project very stressful.

The response to stress is physical and emotional arousal. If the arousal is not too severe, many people enjoy the way stress makes them feel. They are energized and alert, and they feel ready to tackle the challenge. This is the well-known “I do my best work under pressure” crowd. Anxiety sometimes affects test performance this way (Module 8). Short-term, mild anxiety leads to better performance than being completely relaxed.

When the stressors become long term or severe, however, the troubles begin. With persistent stress we are forgetful, have difficulty concentrating, are easily moved to anger and depressed moods, and are overly anxious. We walk out of the mall during the stressful holiday shopping season and spend 15 minutes wandering through the parking lot because we cannot remember where we parked the car. We grind our teeth at night (a sleep disorder called bruxism), which can lead to temporomandibular joint disorder (TMJ), a common cause of jaw discomfort, headaches, and dizziness. We have difficulty sleeping, and are more likely to overeat and use cigarettes, drugs, or alcohol. But did we really have to tell you this? There is little doubt that being under constant high stress for long periods of time is extremely bothersome. It is also dangerous. To understand how stress makes us sick and even kills us, it is important to know why and how our body reacts to stress.

stress: an individual’s physical and emotional arousal in response to a threatening event or situation

stressors: threatening events or situations that might lead to stress

The Stress Response

We have a fast and a slow physical response to stressors, a fact first observed by Hans Selye (pronounced SELL-yay) in the middle of the 20th century (Selye, 1956). The fast response is handled by the sympathetic nervous system, the arousing part of the autonomic nervous system. When your brain recognizes a stressor, the activity of the sympathetic nervous system leads to increased heart rate and blood pressure and reduced digestive activity, among other things (Module 11). Because the nerve endings of the sympathetic nervous system release their neurotransmitters directly to the organs throughout the body, the effects are immediate. One key response is the release of epinephrine, commonly known as adrenaline, by the inside sections of the adrenal glands, which are located on top of the kidneys. Epinephrine and norepinephrine are also released by areas throughout the sympathetic nervous system. When these two chemicals act directly at synapses, they function as neurotransmitters. Some of the epinephrine and norepinephrine also travels through the bloodstream to affect other areas of the body, so they function as hormones as well (and contribute to the slow stress response described below).

sympathetic nervous system: the arousing part of the autonomic nervous system

epinephrine: commonly known as adrenaline, it functions as a neurotransmitter in the fast stress response, and a hormone in the slow stress response

adrenal glands: glands located on top of the kidneys; they release glucocorticoids and epinephrine as part of the stress response

norepinephrine: a chemical produced throughout the sympathetic nervous system; it functions as a neurotransmitter in the fast stress response, and a hormone in the slow stress response

The slow response to stress (which is actually pretty fast but just slower than the fast response; it is a difference of seconds versus minutes) is handled by the endocrine system. The hypothalamus sends signals to the pituitary gland, which releases hormones that travel to the adrenal glands. The outside sections of the adrenal glands release hormones called glucocorticoids, along with epinephrine and norepinephrine. Altogether, these three hormones are known generally as the stress hormones.

Essentially, the sympathetic nervous system and the first release of epinephrine and norepinephrine get the stress response started. The immediate neurotransmitter activity from the sympathetic nervous system along with the slightly slower activity that occurs as these chemicals act as hormones take you through the first few minutes of a stressful situation. This fast response keeps you going until the endocrine system can catch up, a few minutes after the onset of the stressor.

endocrine system: the system of glands that releases hormones throughout the body

glucocorticoids: hormones that are released by the adrenal glands as a major part of the slow stress response

This stress response, which exists to help animals survive during a physical emergency, has been named the fight-or-flight response. Animals, including humans, that can find an extra burst of energy or strength when being attacked by a predator, for example, are more likely to survive. So, the stress response is essentially an evolutionary adaptation. Human ancestors one million years ago who could put on a burst of speed or find the strength to fight off the attacking sabre-toothed tiger were more likely to live and pass on that ability, the stress response, to their offspring.

For many years, researchers considered the fight-or-flight response to be the only stress response that humans have. Shelley Taylor and her colleagues (2000) pointed out that the large majority of research on the physiological responses to stress has been conducted on males, however. When you focus on typical female responses to stress, a different picture emerges. You probably realize that fighting and fleeing are not the only possible ways to survive in the face of a physical threat. In fact, in many situations, they are probably not even the best ways. For example, what if you need not only to survive yourself but to help your offspring to survive as well? You and your offspring might fare better if you focus your energy on seeking the company of other people who can help both you and your offspring to survive. Taylor and her colleagues have named this alternative the tend-and-befriend response, and they note that it is quite common in females. They also note that females in many animal species release more of the hormone oxytocin in response to stress, and evidence has begun to accumulate of similar effects in human females. Oxytocin appears to play an important role in maternal behavior and affiliative behavior and thus may be the key endocrine response that underlies tend-and-befriend. It is probably fair to say that both men and women exhibit both stress responses, but fight-or-flight seems to be more characteristic of men and tend-or-befriend more characteristic of women (Taylor et al. 2000).

fight-or flight response: the name given to the stress response that prepares the body to meet a physical danger by fighting or fleeing from it

tend-and-befriend response: the name given to the stress response that helps the individual cope by nurturing others and seeking social support

oxytocin: a hormone that is released in response to stress and tends to lead to nurturing and affiliative behavior

Why and How Stress Makes Us Sick

There are two basic, serious problems with the stress response in modern humans, whether it is fight-or-flight or tend-and-befriend. First, the stress response is supposed to help us during a physical threat, not a psychological threat. Unfortunately, however, the body reacts the same way to both. Second, the stress response is supposed to take place for a few minutes, not a few weeks. Our stress response evolved to help us face short-term, physical threats, essentially to protect us during an emergency. When we are facing constant psychological stressors, such as a difficult class with daily demands and frequent high-pressure deadlines, the stress response that is designed to help us escape from a physical emergency is activated for days or weeks on end. Making matters worse, humans’ ability to imagine the future leads us to anticipate stressful situations (in other words, to worry), which greatly increases the duration of the stress response, as does our ability to relive the past through our memories. To put it simply, a set of responses that would save our lives in the short term makes us sick and may even kill us in the long term (Sapolsky, 2004).

The list of health risks associated with stress is long and frightening. Most of the risks come from problems with the cardiovascular system and the immune system, but other disorders pop up on occasion, too.

Cardiovascular Problems. A major part of the stress response, particularly the fight-or-flight version, involves the faster delivery of blood to areas of the body that need it to face the emergency. The two main ways this happens (via the sympathetic nervous system and the endocrine system) are through speeding up of the heart rate and constricting blood vessels. The result over the long term is very simple, in a way. Basically, the heart and blood vessels wear down from overuse (Sapolsky, 2004). It makes sense that long-term overactivation of the cardiovascular system would lead it to break down; it is like continuously running a car’s engine at top speed (while not taking care of it, if you consider poor lifestyle choices a side effect of stress).

The result is that long-term stress is associated with a host of cardiovascular disorders. For example, there is an increased risk of the clogging of arteries (known as atherosclerosis), damage to the heart itself, stroke, and sudden heart attack (Brindley, 1995; Kamarck & Jennings, 1991; Rozanski et al. 1991; Waldstein et al. 2004).

Impaired Immune Function. Animal research has shown us that stress—created in the laboratory by separating offspring from mother, disrupting the social or physical environment, or introducing predators, for example—leads to reduced immune function and illness (Ader, 2001; Cohen et al. 1992). Although researchers cannot easily conduct similar studies to manipulate the stress level in humans, several human studies have demonstrated a direct link between stress and illness. For example, one team of researchers exposed a group of research participants to the common cold virus. The participants who reported being under more stress were more likely to develop a cold (Cohen, Tyrrell, & Smith, 1991; Cohen, et al. 1998; 1999). Other studies have shown a direct effect of stress on the functioning of the immune system (Kiecolt-Glaser et al. 1993)

Although our immune system is very complex, it is based on a simple concept: White blood cells, the major cells that fight against infection, can distinguish between normal cells in our bodies and invading foreign cells (mostly based on proteins on the surface of the cells). When white blood cells detect a foreign substance, they attack and destroy it. Different types of white blood cells have different mechanisms, and they attack different kinds of foreign cells, but the basic idea is the same.

One of the key ways that stress influences immunity is through the increase in glucocorticoids. As odd as it seems, the suppression of immunity appears to be what the stress response is supposed to do. A short explanation and this will make sense. Remember the role of the stress response in helping us to survive during a physical stressor. Soon after the onset of the stressor, immune function increases, just the response you need in order to stave off infection from a bite wound, for example. If the immune system stays “switched on” for too long, however, there is a rebalancing of immune function. Prolonged immune activity increases risk of autoimmune diseases, in which white blood cells begin to attack parts of the body in addition to foreign elements. To protect against an autoimmune response, glucocorticoids begin to suppress immune function after its initial boost. With an extended stressor, the period of suppression overwhelms the initial boost and the result is an overall decline in immune function (Sapolksy, 1998). Other parts of the immune system do continue to function at a high level, which can cause damaging inflammation throughout the body (Segerstrom & Miller, 2004).

Cancer. Researchers have suspected for many years that stress contributes to cancer, judging from animal studies and correlational research with humans. For example, one study found a 3.7 times increased risk of breast cancer for women who experienced major stress, daily stress, and depression (Kruk & Aboul Enein, 2004). Some scientists have concluded that suppression of the immune system contributes to some types of cancer (Reiche, Nunes, & Morimoto, 2004). At this point, there is fairly strong evidence allowing us to conclude that stress plays a role in cancer progression. It has been more difficult to establish its role in cancer initiation, but it the evidence is growing here as well (Jenkins, Van Houten, & Bovbjerg, 2014; Soung & Kim, 2015). As you certainly realize, a cancer diagnosis is extremely stressful for most patients and their families (note how threatening and uncontrollable it is). There is also mounting evidence that psychological interventions can help patients and their families reduce distress and can help patients follow doctor’s orders (Andersen et al. 2004; Cillessen et al., 2019; Spiegel & Kato, 1996).

A Bit More on Stressors

Let us finish this section by focusing a bit more on the types of situations that people may find stressful. Again, any event or situation that is perceived as threatening or uncontrollable (or both) will be stressful. Some people find a great many events stressful. And some events are stressful for nearly everybody, such as being the victim of a crime, being involved in a serious accident, or having a close friend or family member die.

Whether other events are perceived as stressful depends more on the interpretation of the person experiencing them. For many people, daily hassles, including congested traffic, are a large source of stress (Ruffin, 1993). Daily hassles like financial burdens, social rejection, or ethnic or racial conflict are quite serious. Others seem trivial, such as disliking daily activities, having too many things to do at once, having difficulty dealing with computers, and being bored at work (Hennessy, Wiesenthal, & Kohn, 2000; Kohn & MacDonald, 1992). But the effects of even these trivial annoyances add up. If you personally find an event threatening or uncontrollable (or both), then it will be stressful.

Debrief

- What are some events that you find stressful that you suspect many other people do not?

- What are some events that many other people find stressful that you do not?

27.2. Coping with Stress

Activate

- What do you do to cope with stress?

- Which of your stress coping activities are the most successful? Which are the least successful?

An individual experiencing stressful events, especially major stressors like the death of a loved one or relentless social rejection, should be keenly aware of the dangers of stress and then take action to combat it. The best solution is to avoid stressors, but of course, that often is not possible. This section focuses on some important aspects of coping with stress in these cases.

General Approaches to Coping

Researchers have distinguished between problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping as general strategies that individuals tend to rely on (Carver, Scheier, & Weintraub, 1989). Some people favor problem-focused coping. They tackle the problem head on and try to solve it, perhaps by increasing their effort, trying to change a situation, or learning some new skills. People who favor emotion-focused coping seek to manage their distressing feelings. You might think that problem-focused coping seems better, as it is directly intended to solve problems, while emotion-focused coping sounds like avoiding a problem and letting it get worse. You would be right, at least some of the time. People who tend to use problem-focused coping do seem to be better adjusted in general. There are exceptions to the advantage, though. For example, if a problem is unsolvable, managing distress might be the only strategy that can help us cope at all. Also, if the distress itself is too disruptive, it might be necessary to manage it before attempting to solve a problem. The best advice is to be ready to use both strategies when appropriate.

Change the Way You Think About Stressors

Do you want to reduce stress? Simple. Do not find events threatening or uncontrollable. Seriously, one important way to cope with stress is to learn how to think about our world differently. Although this can be difficult to do, it is definitely possible, especially with a little help.

Psychologist Martin Seligman (1990) has adapted techniques from cognitive therapy, which is an effective treatment for depression, and demonstrated how individuals can use them to change their style of thinking to cope better with stress. He notes that many people have a tendency to blame themselves when they experience a negative event, and they believe that it will be permanent and affect many aspects of their lives. For example, if you fail an important exam, you might think that it is all your fault, that you will never be able to pass this or any class, and that you will never be able to have a fulfilling career or social life because of your failure. We are sure you can see how this kind of thinking would make many events seem threatening and uncontrollable.

Importantly, researchers have discovered that stress reappraisal, reframing part of the stress response to change its meaning, it can have remarkable effects. For example, Jamieson et al. (2016) taught students who were enrolled in developmental math courses that the stress arousal that they experienced with exams actually helps their performance. Compared to controls who were told to ignore stress feelings, the students who reappraised, reported less test anxiety and they actually did perform better on exams.

Again, although it is not always easy, learning to recognize these unhelpful styles of thinking and adopting new ones is possible. New ways of thinking can help you to realize that you have more control over situations and can also help you to see situations as challenges rather than threats.

Seek Support

People who have good social connections are better able to cope with stress than those who are isolated. Having a close friend, spouse, or family member on whom they can rely during stressful times literally makes people healthier (House, Landis, & Umberson, 1988; Case et al. 1992). For one thing, having a social support network can encourage people to engage in healthier behaviors (Helgeson, Cohen, & Fritz, 1998). On top of that, though, the social network itself appears to provide a direct boost to our ability to fight the negative effects of stress, at least according to research on non-human primates (Coe, 1993; Cohen et al. 1992).

You can get similar effects from simulating social support by writing about stressful experiences. When research participants were instructed to write down their thoughts and emotions about traumatic experiences, they had healthier immune systems and got sick less often than participants who wrote about some other topic (Esterling, et al. 1994; Pennebaker, 1989; Smyth, 1998) Writing about stressful experiences has also improved the immune function of people suffering from HIV infection. (Petrie et al., 2004)

Learn to Relax

Although relaxing is a simple concept, it can be difficult to do. You might think that you are relaxing while watching television when in reality you may still be clenching your jaw, hunching your shoulders, and just generally remaining tense.

Getting some advice or instruction about effective relaxation techniques is helpful for most people. For example, you can use biofeedback to help learn how to relax. Biofeedback is simply a tool that allows you to see aspects of your physical state as some visual stimulus, such as a number. You can learn what types of behaviors can change the numbers, thus changing the physical states. Biofeedback systems use various physical cues as signs of stress level, such as muscular tension or fingertip temperature. Perhaps the most easily accessible is heart rate. You can buy an extremely accurate heart rate monitor for as little as fifty dollars. By trying different behaviors, such as deep breathing or releasing tension in your muscles, you can learn the most effective ways to decrease your heart rate.

Other techniques and activities also promote relaxation. For example, you can use STOP or progressive relaxation techniques (see sec 8.3). The STOP technique is an easy way to distract yourself when you are feeling anxious, so you can engage in some relaxation behavior, such as deep breathing. It simply involves mentally telling yourself to “STOP!” whenever you find yourself getting anxious, then devoting yourself to a short relaxation exercise. Progressive relaxation involves tensing and then relaxing different muscle groups in sequence throughout the body. Simpler forms of relaxation also work. Many people are successful listening to relaxing music, sometimes with progressive relaxation (Pelletier, 2004; Smith & Joyce, 2004). Meditation and yoga may also help reduce stress through relaxation (Canter, 2003; Gura, 2002).

emotion-focused coping: a coping strategy in which people seek to manage their distressing feelings

problem-focused coping: a coping strategy that focuses on tackling the problem head on and trying to solve it

biofeedback: a tool that allows you to see aspects of your physical state, such as muscular tension or heart rate, as some visual stimulus, such as a number

stress reappraisal: reframing part of the stress response to change its meaning

Increase Physical Activity

There is little doubt that physical activity, and specifically aerobic exercise, improves our mood and helps us to cope with stress (Glenister, 1996; Yeung, 1996). In essence, exercise allows the body to do exactly what stress is preparing it to do. A survey of over 12,000 adults found that people who exercised least reported feeling the most psychological stress (Ng & Jeffery; 2003). Researchers Rebar, Stanton, and Geard (2015) conducted a meta-analysis of meta-analyses that indicated that physical activity leads to significant reductions of non-clinical anxiety and depression symptoms (these are milder symptoms that are common among people experiencing stress).

Researchers have been able to show how exercise helps. In one study, individuals who underwent six weeks of aerobic exercise had lower physiological responses (blood pressure and heart rate increases) during stress (Spalding et al., 2004). As you probably know, aerobic exercise improves the cardiovascular system by reducing blood pressure and heart rate in general, so these direct reductions during stressful episodes are on top of the overall benefits of exercise.

Perhaps the best news about exercise is that a little goes a long way. If you want to get the full range of cardiovascular, weight control, and stress reduction benefits, you should follow the recommendations of the US Department of Health and Human Services and get 60 minutes of exercise nearly every day (90 minutes if you need to lose weight). However, people gain most of the stress reduction benefits from getting as little as 10 minutes of exercise per day (Hansen, Stevens, & Coast, 2001). Anyone can exercise this much. All you need to do is purposely park your car at the far end of a parking lot and spend 10 minutes walking briskly to your office, classroom, or workplace, instead of driving around looking for the closest space. Walking back to your car adds another 10 minutes. If you squeeze in one more 10-minute walk, you will have reached another key threshold: The US Department of Health and Human Services reports that 30 minutes of exercise per day will improve health and psychological well-being.

Debrief

- Which of the strategies in this section for coping with stress are behaviors that you use already? Did you think of them as stress coping techniques?

- Which of the strategies in this section for coping with stress do you not currently use? What, if anything, is preventing you from starting to use them?

27.3. Understanding Obesity and Eating Disorders

Activate

- What do you think are the main causes of the large increase in overweight and obese people in the US over the past few decades?

- In what kinds of situations do you probably eat more than you should?

Most people are aware that there is an epidemic of obesity in the US. Although there are a number of different ways to illustrate the alarming state of affairs, let us mention two. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that the percentage of adults who were overweight or obese rose from 55% in the 1988–1994 period to 72% during 2015–2016. Obese individuals alone increased from 22% to 40% of the adult population. Second, 14% of 2 – 5 year-olds, 18% of 6 – 11 year-olds, and 21% of 12 – 19 year-olds were obese in 2015 – 2016 (CDC, 2019).

A key part of these statistics is the definitions of overweight and obese.They are based on the body mass index (BMI), a measure of weight in relation to height. For example, a six-foot person weighing 200 pounds would have a higher BMI (27.1) than a six-foot person weighing 180 pounds (24.4). According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) of the U.S. government, an individual is overweight if he or she has a BMI above 25. A person with a BMI of 30 or above is obese. So, a 6-foot tall person who weighs 184 pounds would be overweight; one who weighs 221 pounds would be obese. The BMI is only a guideline, however, because it does not actually measure body composition. People who are very athletic and muscular sometimes have BMI’s indicating that they are overweight.

To calculate your own BMI, multiply your body weight in pounds by 705, then divide by your height in inches squared.

body mass index (BMI): a measure of weight in relation to height; BMI is used to estimate whether an individual is overweight or obese

overweight: an official designation that corresponds to a BMI above 25

obese: an official designation that corresponds to a BMI of 30 or above

Most people are certainly aware that there are health risks of being overweight, but they might not know the scope of the problem. At the risk of overwhelming you, in order to convey the seriousness of the health risks associated with being obese or overweight, let us give you the exact list of physical ailments that are more likely, as reported by the CDC:

- All-causes of death (mortality)

- High blood pressure (hypertension)

- High LDL cholesterol, low HDL cholesterol, or high levels of triglycerides (Dyslipidemia)

- Type 2 diabetes

- Coronary heart disease

- Stroke

- Gallbladder disease

- Osteoarthritis (a breakdown of cartilage and bone within a joint)

- Sleep apnea and breathing problems

- Many types of cancers

- Low quality of life

- Mental illness such as clinical depression, anxiety, and other mental disorders

- Body pain and difficulty with physical functioning

The key question, of course, is why do so many people weigh too much? Although the full explanation is extremely complex, and we will outline quite a bit of that explanation, one of the most important reasons is that our biological need for food and the reasons that we eat are out of sync. For example, if your schedule allows you only 30 minutes to eat lunch every day at 12:00, you might eat every day at 12:00, whether or not your body needs the food.

Because of this very loose relationship between biological need and eating behavior, environmental cues have a large impact on our eating behavior. As a result, many people end up eating more than their bodies require, and the excess turns into extra weight. For example, suppose an individual requires 2,200 calories to maintain her current weight—a typical recommendation for adult women, although age, metabolism, and activity level affect individual needs, as does gender (National Academy of Sciences, [NAS] 1989). The average US adult is estimated to eat over 2,600 calories per day (US Department of Agriculture [USDA], 2002). You can estimate a ballpark weight gain for the woman in the example by doing a little math. One pound of weight is approximately 3,500 calories, so a 2,600-calorie daily eater might gain one pound every nine days. Although this seems extremely fast, the weight gain would be slow enough that the individual might not notice it for a while; it is less than a “just noticeable difference” (see sec 12.3). Three months later, though, she looks up and realizes that she has gained 10 pounds.

Evolution and Obesity

Human beings have some tendencies that served us well 500,000 years ago but get us into trouble in today’s environment. Throughout evolutionary history, our human ancestors were not troubled by the need to keep off weight. On the contrary, hunters and gatherers needed to be able to preserve body weight when food was scarce.

As a consequence, we have effective physical mechanisms for saving energy but not for dealing with excess energy (Hill & Peters, 1998). For example, in response to fasting, our metabolism rate (the rate of energy use) decreases, so that we can function on fewer calories. Of course, this is a major reason that losing weight through dieting is difficult. Our body realizes that far less energy is entering the system—as if there is a drought and we cannot find enough berries to eat—and enters energy-saving mode.

Many people note, correctly, that there is a significant genetic component to body composition. As usual, however, we are not guaranteed anything by our genes. At best, some people are predisposed to being overweight. Indeed, twin studies have demonstrated that increased activity can help people who might be predisposed to being overweight prevent weight gain (Jackson, Llewellyn, & Smith, 2020).

Here is another sign that genes play a limited role in our current weight problems: The proportion of overweight adults in the US has skyrocketed over the past 40 years, while our genetic composition has likely changed little if at all in that time (CDC, 2019). Further, as cultures throughout the world adopt more Western behaviors—particularly diet—their rates of obesity increase very rapidly (Hebert, 2005). It is implausible that these changes would have much, if anything, to do with genetics.

Environmental Cues That Promote Weight Gain

Evolution also helps explain why there is little relationship between our need for food and our eating behavior. For our human ancestors, when food was available irregularly and was sometimes scarce, a variety of environmental cues encouraged them to eat even though they didn’t need food at the moment. But these cues hurt us today, when a scarcity of food for most people in the US can be solved by a trip to McDonald’s. Many people do not realize how powerful the effects of the “eating environment” are on the amount that we eat. The list of environmental influences on food consumption is enormous, so we will mention only a few of the big—and more surprising—ones.

Social Environment. Social norms, the rules that guide us in group situations, often suggest that overeating is the “correct” thing to do (Module 21). For example, in many families, the norm is to “clean your plate because people all over the world are starving and would do anything to have our food.” (we are not quite sure how our overeating would benefit starving people on the other side of the world.) At the same time, in the broader society, the descriptive norm (the behavioral evidence all around us) is that eating lots of food is exactly what many people do. From the person in front of you at the fast-food restaurant ordering two triple cheeseburgers to the family members taking second and third helpings during holiday meals, we are continually reminded that “everyone eats this much.”

Stress and Emotion. As you have probably heard, and read in the previous section, stress can lead to overeating. For example, when workers reported more stress in their jobs, they ate more calories, sugar, and saturated fat (Wardle et al. 2000). Researchers have also demonstrated that other intense emotions can influence how much we eat. For example, when people are in a depressed mood, dieters eat more and non-dieters eat less (Baucom & Aiken, 1981). Even good moods can lead people who are dieting to overeat. In one study, dieting research participants who watched a comedy or a horror movie ate more food than those watching a neutral movie (Cools, Schotte, & McNally (1992).

The “Mount Everest” Effect. In 1923, mountain climber George Mallory explained that he wanted to climb Mount Everest “because it’s there.” Similarly, we have a strong tendency to eat food simply because it is there. One survey found that 69% of Americans completely finish their restaurant entrees all or most of the time (American Institute for Cancer Research, [AICR], 2003). The problem is those meals have been growing larger. Both for food served in the home and in restaurants, between portion size increased dramatically over the past several decades (Steenhuis I, & Poelman M., 2017). In a study of the Mount Everest effect, researchers allowed participants to eat as many potato chips as they wanted from bags ranging from 28 to 170 grams (28 grams equals 1 ounce, the official serving size for potato chips, which is about 12 to 15 chips). The bigger the bag, the more people ate. Although the potato chip snacks were eaten in the afternoon, the research participants did not correspondingly reduce the amount they ate at dinner, so overall they ended up eating significantly more when they were given the larger bags of chips (Rolls et al. 2004).

Amazingly enough, the Mount Everest effect works even when the food tastes bad. People eating popcorn while watching a movie ate 61% more from a large container than from a small container, even though they had rated the taste unfavorably (Wansink & Park, 2001). It reminds us of an old Woody Allen joke in the movie Annie Hall. He tells of two elderly women complaining about the food at a restaurant. The first one says, “Boy, the food at this place is really terrible.” The other woman replies, “Yeah, I know, and such small portions.”

Even changing the shape of a portion can change the amount that people eat or drink. In a study reminiscent of Jean Piaget’s “failure to conserve” demonstrations with preschool-aged children, adults poured and drank larger quantities of beverages when they were given short wide glasses than when they were given tall thin ones (Wansink and Van Ittersum, 2003).

By the way, George Mallory died trying to climb Mount Everest soon after his famous quotation.

The Role of Marketing. Countless attractive aspects of food are continually communicated to us through the marketing of food products. Although the marketing messages affect all of us, children are especially influenced. A task force of experts convened by the American Psychological Association reported that an average child saw more than 40,000 television commercials per year, many of which are devoted to food. (The four main categories for children’s advertising are toys, cereal, candy, and fast-food restaurants.) The task force noted that children, at least under the age of eight, are unable to critically evaluate ads, so they end up automatically accepting everything in them as true (Kunkel et al. 2004). Researchers have lamented that it is difficult to keep up with the number of advertising messages that reach children today because a great deal of advertising (through online platforms, inserted as part of games, and so on) is very difficult to track (Lapierre et al. 2017). There is no reason to expect that the situation has improved, however.

Signals to overeat and to buy food, hungry or not, work best when they are subtle. For example, marketing messages are more persuasive if you do not realize you are being marketed to—as in product placements in movies and company sponsorships of academic activities in your local elementary school. And if you do not realize that you are eating more potato chips because the bag is bigger, there is nothing to stop you from doing so.

The Other Side of the Coin: Eating Disorders

Overall, about 50% of adults in the US are trying to lose weight, including 26% of people who are normal weight or underweight (Martin et al., 2018). Perhaps it is not surprising that, given the difficulty of losing weight and the large numbers of people trying it, some would fall into the trap of going too far. The result is an eating disorder, one category of psychological disorders. There are several specific eating disorders, but the two best-known are anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa.

Individuals with anorexia nervosa are extremely anxious about being overweight and adopt extreme weight-control measures, such as excessive dieting or exercise. Consequently, the sufferer is extremely underweight. By definition, one can be diagnosed anorexic only if he or she weighs less than the minimum normal weight (for age, gender, and sexual development level). With anorexia nervosa, an individual’s life is literally in danger; serious medical complications can include heart problems, electrolyte imbalance (which can be quite serious), low blood pressure, and increased infections make anorexia nervosa the psychological disorder with the highest mortality rate (Edakubo & Fushimi, 2020). People who are anorexic have distorted views about their own body, which often heavily influences their self-esteem. Many of them thus have symptoms of depression, insomnia, social withdrawal, and anxiety. The very large majority of people who suffer from anorexia nervosa, more than 90%, are female; it typically begins in adolescence (between ages 14 and 18).

Bulimia nervosa is characterized by periods of binge eating (eating large amounts of food) followed by some behavior intended to counteract the overeating. Most famously, the counteracting behavior is self-induced vomiting or using laxatives. Other behaviors can be excessive exercise or fasting. Many people who suffer from anorexia nervosa also have symptoms of bulimia, although bulimia can also appear on its own. Because a bulimic person is not extremely underweight, the disorder can be extremely difficult to discover.

Psychological disorders, including eating disorders, typically have biological, psychological, and cultural or environmental causes. The cultural factors are probably most prominent in eating disorders. Eating disorders are prevalent only where thinness is especially valued, such as wealthy nations where there is plenty of food (Polivy & Herman, 2002). In addition, specific characteristics of families and individuals are more likely to lead to eating disorders. For example, children who are insecurely attached to their parents are more likely to develop eating disorders (Ward et al. 2000). Individual characteristics, such as low self-esteem, are also related to eating disorders (Fairburn et al. 1997). Eating disorders clearly have a genetic component, as well, although heritability estimates vary widely (33% – 84% for anorexia nervosa; 28% – 83% for bulimia nervosa) (Zerwas, Bulik, & Jordan, 2015).

anorexia nervosa: an eating disorder in which the affected individual is extremely anxious about being overweight and adopts extreme weight-control measures. To be diagnosed, the individual must weigh less than the minimum normal weight (for age, gender, and sexual development level)

bulimia nervosa: an eating disorder characterized by periods of binge eating (eating large amounts of food) followed by some behavior intended to counteract the overeating

Debrief

- Come up with examples of a time when each of the following influenced the amount that you ate:

- Social environment

- Stress or emotion

- The Mount Everest effect

- Marketing messages

27.4. Promoting Good Health and Habits

Activate

- What behaviors do you think you should change in yourself to improve your health? What would it take for you to change?

By now, everyone should know that it is dangerous to smoke and to drink alcohol to excess. Most overweight and obese people realize that they should lose weight, and the message about the importance of healthy food choices has made it to most people. Although it is likely true that some public education efforts will continue to help make people aware of problem behaviors, the more interesting question is why people fail to follow the advice. For example, consider exercise. By now, nearly everyone knows that it is important to exercise. According the US Government’s National Center for Health Statistics, only 23% of US adults meet the minimum recommendations of muscle strengthening two times per week and 150 minutes of moderate aerobic (or 75 minutes of intense aerobic) exercise per week (Blackwell & Clarke, 2018)

Why do people not do what they know that they should? Well, the simple, obvious, and not particularly helpful answer is that it is hard. For someone who currently exercises zero days per week, it can be quite a daunting proposal to have to exercise five days per week for at least 30 minutes, plus two days of strengthening exercises. If a non-exerciser jumps up and decides to run four miles, the immediate consequences of that behavior are not likely to be pleasant. The benefits of exercising, being healthier at some undefined time in the future, are too distant and abstract to provide much of an incentive for many people (Module 6). Similarly, the immediate effects of eating a small portion of a healthy food are a bit unsatisfying to someone who would prefer a big piece of French silk pie. Even when people do manage to lose weight over time, they are frequently disappointed when their bodies do not look like the bodies of models and actors.

One secret to getting people to change their behavior is to discover how people who have been successful did it. Psychologist James Prochaska spent many years examining the question of how people successfully change. He looked for common factors among different psychotherapies that promote behavior change, as well as the strategies and processes used by successful “self-changers” (Prochaska, 1979; Prochaska & DiClemente, 1982; Prochaska, DiClemente, & Norcross, 1992). His theory, the transtheoretical theory of change, describes how people progress through five separate stages on the road to successful behavior change, whether the problem is overeating, lack of exercise, smoking, drinking, or any other maladaptive behavior:

Precontemplation. This is not really a stage of change as much as a stage in which the individual is not yet ready to change. The individual in the precontemplation stage resists change, perhaps becoming defensive when other people try to help, often not realizing that he or she has a problem, and thinking that it is other people who need to change. For example, a middle-aged man in precontemplation may believe that exercising is overrated and potentially dangerous, citing the research that suggests that there is a significant risk of dying of a heart attack while exercising. (there is an increased risk of sudden heart attack during exercise, but this small temporary increase is more than offset by the overall decrease in risk of death from being in good shape.) A precontemplator’s occasional half-hearted attempts to change are practically guaranteed to fail, and the result is often worse behavior (Prochaska, Norcross, & DiClemente, 1994). Do not buy the sedentary man a $1000 membership at the local health club for his birthday. Health clubs make a fortune on people who join and pay a monthly fee to remain a member but never once use the facilities. One study found that over 500,000 people in the United Kingdom had health club memberships that they had never used (Men’s Health, 2004). The immediate goal for the precontemplator is simply to start thinking about changing and thus moving into the next stage. To do this, the individual must become aware of the problem and of his or her defenses against changing. Of course, the precontemplator is not motivated to admit to a problem. Nearly always, the awareness must be raised with the help of the outside environment. For example, a visit to the doctor or the death of a sedentary friend might get the precontemplator to start thinking about the problem. Other times, family and friends play an important role in helping the person become aware.

Contemplation. Once our non-exerciser realizes that he has a problem, he realizes that he should change and begins to consider the options seriously. He may actively seek information about the problem and is open to talking and thinking about it. Commonly, though, people get stuck in contemplation—that is, they continue to think about a problem as a way of avoiding taking any action. On the other hand, a common way to fail is to jump into action before the person has had enough contemplation. Again, the real goal is simply to move on to the next stage. To do this, the person should collect specific information about the problem and potential solutions and begin to set specific goals. For example, the non-exerciser can learn about the relative importance of strengthening and aerobic exercises, as well as the actual recommended levels of each for a man his age. He may decide that he would like to work toward two days of strength training and three days of aerobic exercise per week.

Preparation. This stage need not last long, but it is essential to successful change. It is time to turn the goals from the contemplation stage into specific steps. Preparation is also a kind of transition stage, with elements of both contemplation and action. Our exerciser may continue to collect information, as in the contemplation stage, while he begins to draw up a specific exercise plan. At the same time, he may begin to make small changes in his daily activity, such as taking the stairs instead of the elevator or parking his car farther away from the office door every morning before work. A major danger at this point is to try to change too quickly. A non-exerciser who decides after a week of walking the length of the parking lot twice a day that he can try jogging four miles on Saturday morning is not likely to be successful. For this stage, it is enough to make small changes, create a set of specific steps, anticipate some potential problems, and make a commitment to change. The commitment should be specific and public. Then, our non-exerciser may be ready to move on to the fourth stage.

Action. Even after successfully making it through the previous stages, the changes will not be easy. If the person has planned for the likely difficulties, however, they can be surmounted. Two key strategies are countering and avoiding. When you counter, you engage in a behavior that is a contradiction of the problem behavior. For example, if our non-exerciser has an urge to plop down in front of the TV, that is the perfect time to go for a walk around the block. When you avoid, you remove the tempting stimuli. If you eat too many cookies, for example, stop buying cookies. You cannot eat them if they are not in the house. It is important to realize that you need not have superhuman willpower (see self control in Module 20) . If our non-exerciser is serious about stopping watching TV, he can unplug it and move it into another room, so that any time he wants to watch it he has to go to the effort of retrieving it and plugging it in. Finally, there are a great many additional techniques that can be borrowed from psychology to help initiate the changes. Perhaps the best are positive reinforcement and shaping from operant conditioning (Module 6). In other words, rewarding oneself for gradually approaching the desired behavior is an excellent strategy that can be used to facilitate nearly any change.

Maintenance. During the final stage, one attempts to make the change a permanent part of one’s lifestyle. At one level, maintenance is simply a matter of realizing that difficulties, backtracking, and obstacles will continue. It may be necessary to make other changes to help maintain the new behaviors. For example, in order to avoid television in order to find time to exercise, it may be necessary to avoid television at other times as well, so it becomes less of a habit. Our new exerciser may have to change his social routine if his old friends continue to be sedentary.

As our non-exerciser attempts to move from precontemplation through the intermediate stages to action, he will undoubtedly have many opportunities to think about the pros and cons of changing. For example, he may tell himself that if he begins exercising he will have more energy and sleep better (pro) or that he will have less time for other leisure time activities (con). Successful changers are able to increase their perception of the pros as they move from precontemplation to contemplation and then decrease their perception of the cons as they move from contemplation to preparation to action and finally to maintenance. Our non-exerciser, then, should focus on his perceptions at the right times when he gathers information, thinks about, plans for, begins, and maintains his new regimen of exercise.

transtheoretical theory of change: a theory that describes how people progress through five separate stages on the road to successful behavior change

Debrief

- Recall the behaviors that you identified in the Activate exercise as behaviors you should change. For each one:

- Which of Prochaska’s stages are you currently in?

- How do you think you might be able to move yourself to the next stage?

- What is preventing you from moving to the next stage?

an individual’s physical and emotional arousal in response to a threatening event or situation

the division of the autonomic nervous system that arouses the body.

commonly known as adrenaline, it functions as a neurotransmitter in the fast stress response, and a hormone in the slow stress response

glands located on top of the kidneys; they release glucocorticoids and epinephrine as part of the stress response

the main neurotransmitter used by the sympathetic nervous system

the system of hormone-producing glands located throughout the body

hormones that are released by the adrenal glands as a major part of the slow stress response

the name given to the stress response that helps the individual cope by nurturing others and seeking social support

a hormone that is released in response to stress and tends to lead to nurturing and affiliative behavior

a coping strategy that focuses on tackling the problem head on and trying to solve it

a coping strategy in which people seek to manage their distressing feelings

reframing part of the stress response to change its meaning

a tool that allows you to see aspects of your physical state, such as muscular tension or heart rate, as some visual stimulus, such as a number

a measure of weight in relation to height; BMI is used to estimate whether an individual is overweight or obese

an official designation that corresponds to a BMI above 25

an official designation that corresponds to a BMI of 30 or above

an eating disorder in which the affected individual is extremely anxious about being overweight and adopts extreme weight-control measures. To be diagnosed, the individual must weigh less than the minimum normal weight (for age, gender, and sexual development level)

an eating disorder characterized by periods of binge eating (eating large amounts of food) followed by some behavior intended to counteract the overeating

a theory that describes how people progress through five separate stages on the road to successful behavior change