2 Fallacies

Introduction

Ever since Aristotle helped to clearly express the principles of logic, logicians have tried to develop quick and readily available means to identify errors in reasoning. Some errors in reasoning are easy to identify and some are difficult to spot. Often this is due to rushing to conclusions or listening poorly to what is stated in the premises. When these errors are excessive, we spot them easily.

For example, if our friend is worried about the grade they got on a math exam, they may try to tell you:

I’m totally going to fail this class. I mean, I just got a C on the midterm exam!

You can probably see they are overreacting to one grade. You likely also see that the grade they are reacting to is not even a failing mark itself. Their mind is leaping to a definitive conclusion on the basis of one premise that cannot support the truth of such a claim with that much certainty.

Let’s try some other examples. Consider the following two statements:

- If I have twenty dollars, I will get a music album.

- I got a music album.

And pause.

Stop for a second and consider those two statements. Take a moment to consider what comes next. Where does your mind leap? (Write it down, we’ll come back to it later.)

Let’s try another example. Consider the following statements:

- Marx tried to explain what is wrong with capitalism, the kind of social and economic system we have in the United States.

- Of course, Marx was a tree-hugger communist who hated Americans.

Again, where does your mind leap? (Write that down too; we’ll come back to both of these examples.)

Sometimes, even when we are careful and trying to think clearly, figuring out if our minds have done a good job in drawing conclusions is not easy. This is where many of the tools of logic come into play. Over the last two thousand years a very wide range of tools have been developed, too many to cover in this class. However, we should be familiar with two general types of error: formal and informal fallacies.

Why We Study Fallacies

A logical fallacy is simply an error in reasoning. These errors are useful to learn, as they help us identify flaws in our own thinking as well as errors in what other people present to us.

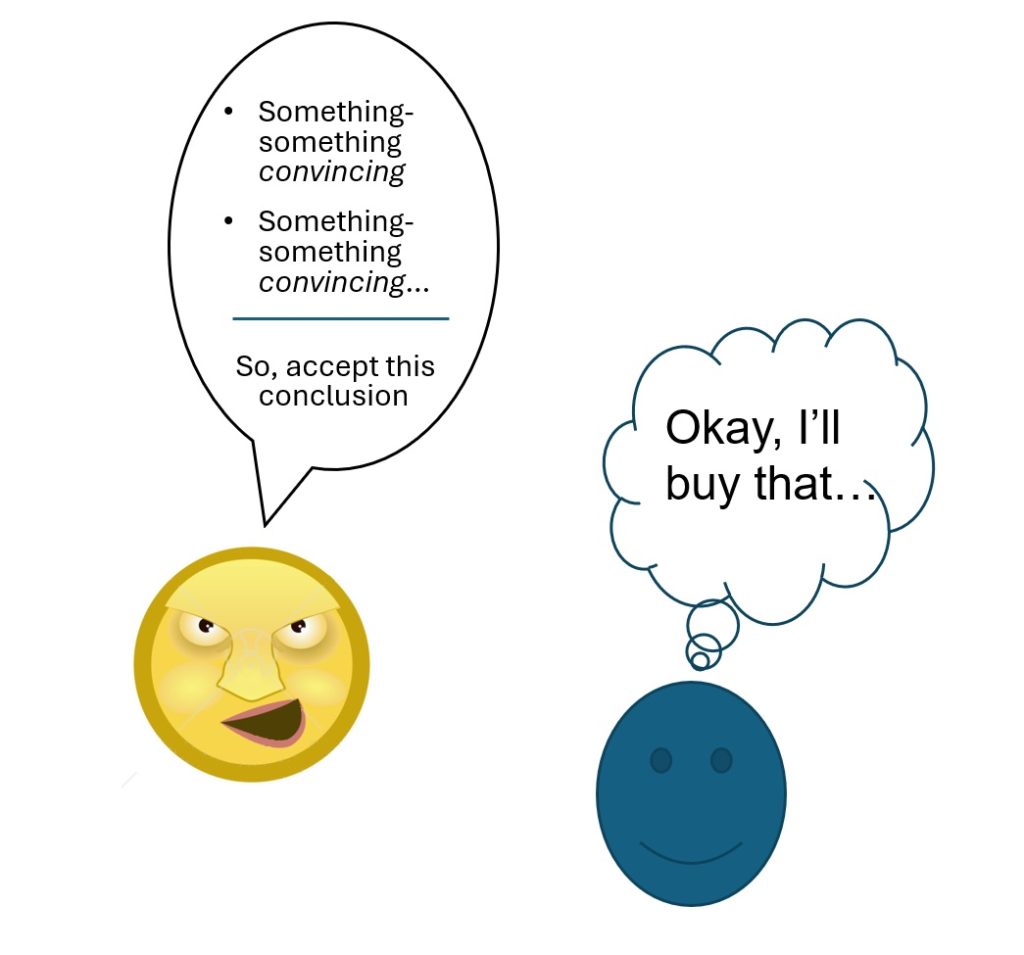

While they may represent “bad” reasoning in many senses, we should not belittle the importance of fallacies. A great deal of bad thinking is actually very convincing. That fact should alarm us. So, I will say it again to make it stick:

A lot of bad thinking is very convincing.

Put differently:

We study fallacies because they work.

Though they measure poorly by standards of reasoning, they are effective in getting people to draw conclusions that are either invalidly concluded or weakly inferred. Studying fallacies empowers us to use our own minds more effectively by not repeating these errors as well as safeguard ourselves (and those close to us) from the influence of these errors.

Formal Fallacies

Some fallacies can be identified simply by virtue of the sentence structure found in an argument. We call this sentence structure “syntax” to recognize that we are talking simply about how statements are logically formed.

Formal Fallacy: an error of reasoning found solely in the syntax (form) of an argument’s statements resulting in an invalid argument form.

We will explore this in much more detail in later chapters, but for now we can revisit our first example above.

- If I have twenty dollars, I will get a music album.

- I got a music album.

Take a look at the first statement. This has a special kind of syntax, a special kind of structure in how the statement is formed: it is a conditional statement. The structure is pretty easy to recognize:

IF (fill in the blank), THEN (fill in the blank).

In seeing this structure, we don’t really care what is in the blank spots. We just see that all conditional statements have this important structure:

They have an “if-clause”

They have a “then-clause”

We even see this when the word “then” is not present, as we have in our example. Another way to say this is that even when small changes are made, we can still recognize the same form of a conditional statement. “Form” is another way to say “syntax” or “structure.”

For a conditional statement, the if-clause has a name: we call it the antecedent. The then-clause is called the consequent.

When one of our premises is a conditional statement, we may find that another premise has a very specific relationship to one of the clauses in the conditional. In our example, the second premise is affirming the truth of the “then-clause.” This is a pattern. We can spot this pattern in the raw form of how the argument’s premises relate to one another. More importantly, the pattern that is emerging is often completed in the leap of the mind we make. Many folks will conclude:

“I had twenty dollars.”

Put differently, many folks will conclude that the conditional’s antecedent (the if-clause) is true. The full pattern is now easy to see:

- If (antecedent), then (consequent).

- The (consequent) is true.

Therefore, the (antecedent) is true.

This is the argument’s full pattern (i.e., the argument’s full form). This particular pattern is so common that logicians saw fit to name it: we call it “Affirming the Consequent.” This pattern is also invalid.

To understand why this argument is invalid, we can produce a counterexample: a demonstration of how the two premises can be true, yet the conclusion false. For example, I say:

- It is true that if I had twenty dollars, then I would have gotten a music album.

- It is true that I got a music album—it was given to me as a gift because I am broke.

So, it is false that I had twenty dollars.

The counterexample shows that from these two premises we cannot confidently conclude that I had twenty dollars. This would be a sketchy leap of the mind.

Note that even if we take “I would get a music album” to mean “I bought a music album,” we still cannot avoid an invalid inference if we try to reason this way. Consider:

- It is true that if I had twenty dollars, then I would have bought a music album.

- It is true that I bought a music album.

So, I had twenty dollars.

Our counterexample could look like this:

- It is true that if I had twenty dollars, then I would have bought a music album.

- It is true that I bought a music album—it was on a half-off sale, which is good because all I had was $10.

So, it is false that I had twenty dollars.

You might think that you are being duped in these examples, as though the counterexamples are tricks. This is not so. The counterexamples are developed just to help us see one very simple thing: the possibility exists that the premises can be true and yet the conclusion false. That is:

Counterexamples demonstrate an actual possibility that the argument has all true premises and a false conclusion (i.e., it is invalid).

In every such instance, the counterexample helps us see that we are stretching our mind to claims that lie beyond what a conditional statement can support. In later chapters we will look extensively at conditional statements, for they are notoriously difficult to properly understand.

Affirming the Consequent is a common formal fallacy. Indeed, saying it is “common” is an understatement. Generation after generation, people all over the world have made this exact same mistake dozens, hundreds, perhaps thousands of times. We would do well to remember this formal pattern so we can avoid more of the same error in how our own mind leaps.

Let’s look at another common formal fallacy. Consider the following:

If I go to the store, I’ll get some milk.

Pause now. Did you notice how this is once again a conditional statement? As it turns out, many people struggle to understand just what a conditional statement is asserting. Because they misunderstand it, they are prone to make errors in thinking through it.

Continued, we might discover that:

- If I go to the grocery store, I’ll get some milk.

- I did not go to the grocery store.

Q: Where does your mind leap?

Many folks will conclude on the basis of these two statements that:

“I did not get some milk.”

If that’s what you concluded, you are not alone…nor are you correct. We have no firm basis to claim that we did not get the milk. In short, this is an invalid inference. Here’s the formal pattern:

- If (antecedent), then (consequent).

- The (antecedent) is false.

Therefore, the (consequent) is false.

This pattern is called Denying the Antecedent, due to how we rely upon in the second premise to arrive at our conclusion. This is a well-known formal fallacy. Our conclusion is on shaky ground, and a counterexample makes it easy to see why:

- If I go to the grocery store, I’ll get some milk.

- I did not go to the grocery store.

I did get some milk—the coffee shop had some.

The savvy student may start to pick up on what is going wrong in the leap our minds make when we commit such formal fallacies. In both Denying the Antecedent and Affirming the Consequent, we are misunderstanding what the conditional statement really means. We jump the gun, and our mind leaps to a claim that is not supported.

We think the conditional statement will allow such a jump, because we think the conditional statement asserts a very strong relationship between the if-clause and the then-clause. It does not.

An “if-then” statement makes it look like we are safe to make strong connections between both clauses. Sometimes it does, but not always. Later we will study conditional statements at length and learn how to safely make guaranteed claims based on them. For now, at least we know there are these two decidedly unsafe ways to make claims based on them.

Before moving on to the informal fallacies, we should note that the unsafe inferences we just learned have a special quality to them. They are both based on a misunderstanding of a connection between two statements (i.e., the two clauses). These connections are very important to understand. For example, the “if-then” connection is notoriously tricky—until we understand it, after which it is really quite straightforward. These “connections” between the component statements are what create the “form” of the overall statement. Successfully asserting the truth (or painfully insisting on falsehood) often rests entirely on the form of our overall statements. The content of our claims matters little if we are lost in the connections made between them.

Informal Fallacies

Many errors of reasoning are found in poor use of syntax. In later chapters we will focus our study on syntax to avoid these errors. However, these are not the only kinds of errors regularly found in arguments. There are other patterns, patterns found not in the form of the statements, but patterns in how those statements are used in an argument. These non-formal patterns are called informal fallacies.

Informal fallacies are often described as errors that occur in the content of an argument. So if “form” is like shape, “content” is what fills that shape. We do not need to know the content of the “if-clause” in a conditional statement to see errors like Denying the Antecedent, because it is a formal fallacy. Yet in an important sense, we often do need to know the content of the antecedent in order to see an informal fallacy at play.

I should stress that seeing content alone is not enough. Knowing the meaning of a statement alone does not reveal the pattern of an informal fallacy. For our purposes, we will do better to think more in terms of what one does with language. For the informal fallacies are more akin to what one does with their claims than what their actual claims may mean.

Informal Fallacy (a working definition): an error in reasoning found in the patterns of what is done in an argument, specifically in how the statements are used to create influential strategies with little logical merit.

Why We Study the Informal Fallacies

Informal fallacies are a misuse of influential strategies. They are often committed because, like all fallacies, they WORK. We should not be surprised to see bookshelves filled with authors proposing to teach people how to win friends and influence people. People have complex psychological and emotional lives. We can use words to tap into these driving forces to influence people, to get them to accept conclusions even when we have not given proper support for the truth of those conclusions.

In short, “how to win friends and influence people” is nothing short of manipulation.

While there are additional serious concerns over the ethical quality of these strategies, above all, these are not logically respectable methods. These are the informal fallacies.

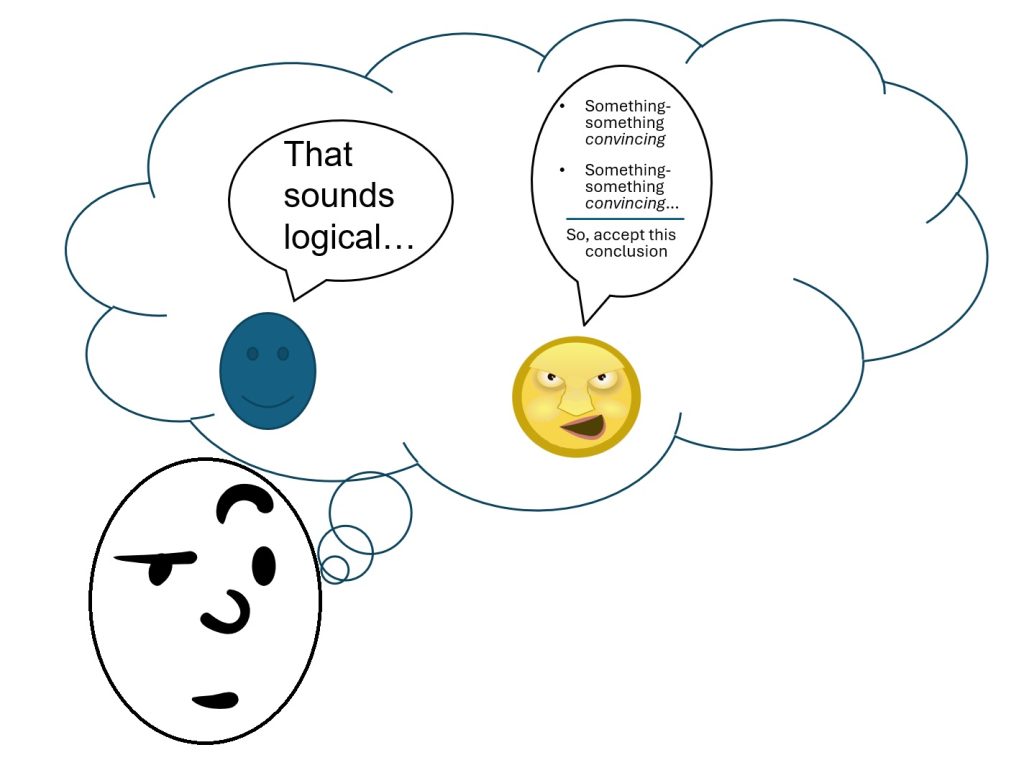

Our approach to the informal fallacies will be to think of them as shady strategies used to convince us of a conclusion. Strictly speaking, these patterns of argument (i.e., “strategies”) are frequently committed innocently. Many folks are not aware their arguments follow these patterns, or they are not aware there is something wrong with these patterns. Still, framing the informal fallacies as shady strategies is useful in understanding them and the context in which they are often used.

There are two main characters in this approach:

The Author: the person who is giving the argument

The Audience: the person(s) who receives the argument

The author of a fallacy is using some kind of nefarious tactic to land his/her conclusion. They often know that providing a logically compelling argument for their conclusion is difficult. Winning over their audience with the best respectable argument that they can muster will be too hard for them. So, they take the easy way out. They give an argument which has little respectability but high “convince-ability.” If we are not careful, we will fall for their game. They will dupe us like a con artist who plays us for fools (and in truth we would be foolish to accept their arguments).

What makes all of this even more challenging is that “the author” and “the audience” are sometimes the same person. As odd as that sounds, if we are prone to using these strategies, we often use them on ourselves. We can convince ourselves of things using the same con-man strategies that others would use when they are manipulating us. The informal fallacies can be so powerful that we do not see that we can play ourselves.

Organizing Informal Fallacies

Logicians have identified many informal fallacies, far too many for us to cover at the moment. So, we will look at a few of the more common and troubling ones. This is by no means a complete list, and students should be aware that any list of fallacies reflects a given logician’s sense of the errors of reasoning that are most important to cover.

We will group the fallacies we cover into three sets with common qualities. This should help us see the similarities among the fallacies.

- Set I: Errors of Relevance

- Set II: Appeals to Unwarranted Assumption

- Set III: Weak Induction

Keep in mind that all the fallacies in each set share a common quality. For example, all the fallacies in the Relevance set will be variations on a common theme: presenting irrelevant premises. As it turns out, there are many ways in which an author can present irrelevant premises. These ways are strategically different, each using a spin on the general tactic of using irrelevant claims to convince their audience to accept their conclusion. The same is true of the other sets—within the sets, the fallacies are all variations on a common theme.

Additionally, we will often identify fallacies as a “special type” of a broader fallacy. This is done to help the reader understand the important twists they may see in a given strategy.

Table of Informal Fallacies

SET I: Errors of Relevance

Ad Hominem

Hypocrisy

Genetic Fallacy

Straw Man

Appeal to Consequences

Appeal to Desire

Bandwagon (Appeal to the People)

Appeal to Force

Appeal to Pity

Red Herring (Avoiding the Issue / Evasion)

Smokescreen

SET II: Appeals to Unwarranted Assumption

Begging the Question

Inappropriate Authority

False Dilemma (False Dichotomy)

Loaded Question

Gaslighting

SET III: Weak Induction

Hasty Generalization

Cherry Picking

Appeal to Ignorance

Conspiracy Theory (Canceling Hypothesis)

Faulty Causality (False Cause)

Slippery Slope

Gambler’s Fallacy

SET I

Errors of Relevance

What all fallacies of relevance have in common is that they make an argument or response to an argument that is irrelevant to that argument. These strategies seek to distract the audience from subjects or claims that are relevant to the argument at hand.

Fallacies of relevance can be psychologically compelling, but it is important to distinguish between rhetorical techniques that are psychologically compelling, on the one hand, and rationally compelling arguments, on the other. What makes something a fallacy is that it fails to be rationally compelling once we have carefully considered it. That said, arguments that fail to be rationally compelling may still be psychologically or emotionally compelling.

Ad Hominem

“Ad hominem” is a Latin phrase that can be translated into English as the phrase “against the man.” In an ad hominem fallacy, instead of responding to (or attacking) the argument a person has made, one attacks the person him or herself. In short, one attacks the person making the argument, rather than the argument itself.

The “ad hom” is one of the most powerful (and thus, troubling) fallacies there is, in large part because people like to think about people. One might even say that as social creatures we are deeply hardwired to think about other people. We are not nearly so hardwired to think about abstract ideas or logical relationships. So, our thoughts are easily led to what we prefer thinking about—people.

There are a few different subvariants of this strategy. Most classically, the ad hominem fallacy attempts to discredit an argument because the source of that argument (i.e., the author of it) is a bad person. Importantly, the author of this fallacy rarely aims this argument at that person. In other words, this is not a strategy typically used in direct debate between two parties. The ad hom’s intended audience is usually someone else who is not present at the time. The goal of the strategy is to get the audience to reject “the bad person’s argument” simply because they are a bad person. For example:

“Look Mary, I know Mike likes to talk a lot about his faith and why he’s so convinced his religious beliefs are true. But really now, we can’t take anything he says seriously. He’s just another religious nutjob who thinks he’s found God.”

Notice how the author of this argument uses the main elements of this fallacy:

- Makes it clear that he is aware that Mike has made arguments for his beliefs

- Is not engaging with those arguments themselves

- Tries to convince Mary to reject those arguments based on insults to Mike’s intellect and integrity

Ad hominem arguments bank on the audience being unwilling to accept things that “bad people” say. So, the author of an ad hominem will typically highlight some aspect of the person’s character they think they can paint in a negative light or that they expect their audience to grasp on their own.

For example, suppose that Hitler had constructed a mathematical proof in his early adulthood (he didn’t, but just suppose). A contemporary author of an ad hominem fallacy probably does not need to say anything bad about Hitler. They will rely on their audience to already believe that Hitler = bad. Yet the validity of Hitler’s mathematical proof should stand on its own; the fact that Hitler was a horrible person has nothing to do with whether the proof is good. Likewise with any other idea: ideas must be assessed on their own merits, and the origin of an idea is neither a merit nor demerit of the idea.

Of course, the author may find other ways to zero in on a person’s negative traits. So, there are variants of this nefarious strategy that use:

A person’s conduct: See the Hypocrisy (Tu quoque) fallacy

A person’s situation: See the Genetic fallacy

We will look at these next, but keep in mind the general structure of all ad hominem strategies:

- Being aware of an argument made by someone else

- Avoiding evaluating the other person’s argument

- Calling out something negative about the origin of that argument

- Using those negative things as a basis to reject the argument

This last element is important to keep in mind. An ad hominem strategy has a purpose—to convince the audience to reject an argument. If an author is simply calling someone names, belittling them, or otherwise being mean-spirited in their reference to them, but they are not trying to use that as the support for rejecting their argument, then they are not committing an ad hominem fallacy. Their bad language, crude behavior, or even immorality may just mean they are a mean person. Yet even mean people can muster quality arguments.

Hypocrisy (a.k.a. Tu quoque)

“Tu quoque” is a Latin phrase that can be translated into English as “you too” or “you, also.” The basic strategy in this Hypocrisy fallacy is again to ignore the argument given by others in favor of looking at some aspect of the person making that argument. In this case, the author of a hypocrisy fallacy looks at what another person does rather than evaluate their argument. Their character is not used against them directly; instead, their conduct is used against them.

The tu quoque fallacy is used in two ways:

First: as a way of avoiding answering a criticism by bringing up a criticism of your opponent rather than answering the criticism.

Second: as a way of avoiding evaluation of an argument made by others by bringing up their own conduct as evidence that their argument should not be taken seriously.

Let’s look at the first way the hypocrisy fallacy is used.

For example, suppose that two political candidates, A and B, are discussing their policies and A brings up a criticism of B’s policy. In response, B brings up her own criticism of A’s policy rather than respond to A’s criticism of her policy. B has committed the tu quoque fallacy. The fallacy is best understood as a way of avoiding having to answer a tough criticism that one may not have a good answer to. This kind of thing happens all the time in political discourse. This is also a specific case in which the author’s intended audience (of the basic ad hominem strategy) is the very same person whose argument is rejected.

Tu quoque, as I have presented it, is fallacious when one raises a criticism simply to avoid having to answer a difficult objection to one’s argument or view. However, there are circumstances in which a tu quoque response is not fallacious. So, be careful in judging someone this way. Let’s look at a situation in which it might look like a nefarious tactic is being used, but in reality is not.

If the criticism that A brings toward B is a criticism that equally applies not only to A’s position but to any position, then B is right to point this fact out. For example:

Suppose that Allen criticizes Billy for taking money from special interest groups. In this case, Billy would be totally right to respond that not only does Allen take money from special interest groups, but every political candidate running for office does. Billy is not accusing Allen of hypocrisy. He is pointing out that his own conduct is not unique (it’s the same as Allen and everyone else’s conduct) and thus not a basis for critique. That is just a fact of life in American politics today.

So Allen really has no criticism at all of Billy since everyone does what Billy is doing and it is in many ways unavoidable. Thus, Billy could (and should) respond with a “you too” rebuttal, and in this case, that rebuttal is not a tu quoque fallacy.

Now let us look at the second use of the Hypocrisy fallacy.

Here is an anecdote that reveals an ad hominem fallacy.

In an ethics class, students read the work of Peter Singer. Singer had made an argument that it is morally wrong to spend money on luxuries for oneself rather than give all of your money that you don’t strictly need away to charity. The essence of the argument is that there are every day in this world children who die preventable deaths, and there are charities who could save the lives of these children if they were funded by individuals from wealthy countries like our own.

In response to Singer’s argument, one student in the class asked:

“Does Peter Singer give his money to charity? Does he do what he says we are all morally required to do?”

The implication of this student’s question was that if Peter Singer himself doesn’t donate all his extra money to charities, then his argument isn’t any good and can be dismissed. But that would be to commit the ad hominem fallacy of Hypocrisy. Instead of responding to the argument that Singer made, this student attacked Singer himself. That is, they wanted to know how Singer lived and whether he was a hypocrite or not. Was he the kind of person who would tell us all that we had to live a certain way but fail to live that way himself? But all of this is irrelevant to assessing Singer’s argument.

To see this, we only need to rationally evaluate the student’s proposal. Suppose that Singer didn’t donate his excess money to charity and instead spent it on luxurious things for himself. Even if it were true that Peter Singer was a total hypocrite, his argument may nevertheless be rationally compelling. And it is the quality of the argument that we are interested in, not Peter Singer’s personal life and whether or not he is hypocritical.

Whether Singer is or isn’t a hypocrite is irrelevant to whether the argument he has put forward is strong or weak, valid or invalid. As a good logician, the student should be focused on these qualities of the argument. The argument stands on its own and it is that argument rather than Peter Singer himself that we need to assess.

Nonetheless, many of us still find something psychologically compelling about the question: Does Peter Singer practice what he preaches? I think what makes this question seem compelling is that humans are very interested in finding “cheaters” or hypocrites—those who say one thing and then do another. We want to think about people. That said, whether or not the person giving an argument is a hypocrite is irrelevant to whether that person’s argument is good or bad.

As before, we need to be careful in judging someone’s argument as an example of this fallacy. Not every instance in which someone attacks a person’s character is an ad hominem fallacy. Suppose a witness is on the stand testifying against a defendant in a court of law. When the witness is cross-examined by the defense lawyer, the defense lawyer tries to go for the witness’s credibility, perhaps by digging up things about the witness’s past.

For example, the defense lawyer may find out that the witness cheated on her taxes five years ago or that the witness failed to pay her parking tickets. This isn’t an ad hominem fallacy because in this case, the lawyer is trying to establish whether what the witness is saying is true or false. In order to determine that, we have to know whether the witness is trustworthy. These facts about the witness’s past may be relevant to determining whether we can trust the witness’s word. In this case, the witness is making claims that are either true or false rather than giving an argument.

In contrast, when we are assessing someone’s argument, the argument stands on its own in a way the witness’s testimony doesn’t. In assessing an argument, we want to know whether the argument is strong or weak and we can evaluate the argument using the logical techniques surveyed in this text.

In contrast, when a witness is giving testimony, they aren’t trying to argue anything. Rather, they are simply making a claim about what did or didn’t happen. So although it may seem that a lawyer is committing an ad hominem fallacy in bringing up things about the witness’s past, these things are actually relevant to establishing the witness’s credibility.

Genetic Fallacy

The genetic fallacy is a variant of the basic ad hominem fallacy. This fallacy occurs when one argues (or, more commonly, implies) that the origin of something (e.g., a theory, idea, policy, etc.) is a reason for rejecting (or accepting) it.

For example, suppose that Jack is arguing that we should allow physician-assisted suicide and Jill responds that that idea first was used in Nazi Germany. Jill has just committed a genetic fallacy because she is implying that because the idea is associated with Nazi Germany, there must be something wrong with the idea itself. What she should have done instead is explain what, exactly, is wrong with the idea, rather than simply assuming that there must be something wrong with it since it has a negative origin. The origin of an idea has nothing inherently to do with its truth or plausibility.

The basic strategy of this variant is to hide a straight-up attack on a specific individual who came up with an idea in favor of a generic reference to the group or the time period in which an idea developed. Of course, we know that ideas do not grow on trees. So, this strategy always implicitly relies on calling out some person(s) who developed the idea—and they are bad people, so this is a bad idea.

Although genetic fallacies are most often committed when one associates an idea with a negative origin, it can also go the other way: one can imply that because the idea has a positive origin, the idea must be true or more plausible.

For example, suppose that Jill argues that the Golden Rule is a good way to live one’s life because the Golden Rule originated with Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount (it didn’t, actually, though Jesus does state a version of the Golden Rule). Jill has committed the genetic fallacy in assuming that the (presumed) fact that Jesus is the origin of the Golden Rule has anything to do with whether the Golden Rule is a good idea.

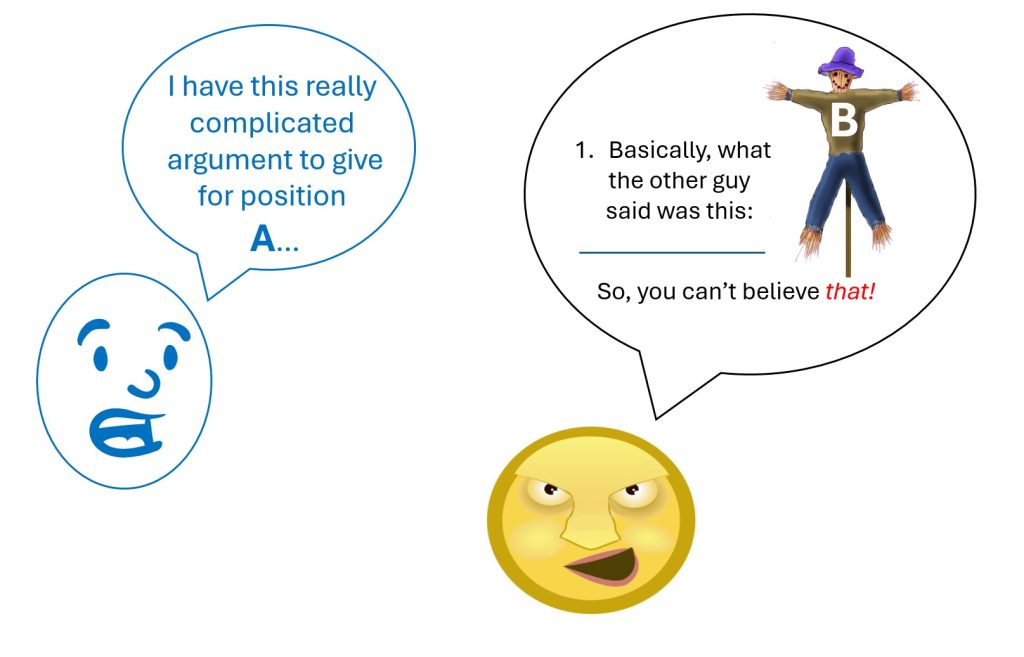

Straw Man

Suppose that my opponent has argued for a position, call it position A, and in response to his argument, I give a rationally compelling argument against position B. That sounds like a foolish thing to do! After all, my opponent is arguing for position A. So why did I argue against position B?

Answer: Because position B is related to position A, but is much less plausible (and thus much easier to refute). What I have just done is attack a straw man—a position that “looks like” the target position, but is actually not that position.

Straw men are easy to knock down. When one attacks a straw man, one commits the straw man fallacy. The straw man fallacy misrepresents one’s opponent’s argument and is thus a kind of irrelevance.

Here is an example:

Two candidates for political office in Colorado, Tom and Fred, are having an exchange in a debate. Tom has laid out his plan for putting more money into health care and education. Fred has laid out his plan, which includes earmarking more state money for building more prisons, which will create more jobs and thus strengthen Colorado’s economy. Fred responds to Tom’s argument that we need to increase funding to health care and education as follows:

“I am surprised, Tom, that you are willing to put our state’s economic future at risk by sinking money into these programs that do not help to create jobs. You see, folks, Tom’s plan will risk sending our economy into a tailspin, risking harm to thousands of Coloradans. On the other hand, my plan supports a healthy and strong Colorado and would never bet our state’s economic security on idealistic notions that simply don’t work when the rubber meets the road.”

Fred has committed the straw man fallacy. Just because Tom wants to increase funding to health care and education does not mean he does not want to help the economy. Furthermore, increasing funding to health care and education does not entail that fewer jobs will be created. Fred has attacked a position that is not the position that Tom holds, but is in fact a much less plausible, easier to refute position. However, it would be silly for any political candidate to run on a platform that included “harming the economy.” Presumably no political candidate would run on such a platform. Nonetheless, this exact kind of straw man is ubiquitous in political discourse in our country.

Here is another example.

Nancy has just argued that we should provide middle schoolers with sex education classes, including how to use contraceptives, so that they can practice safe sex should they end up having sex. Fran responds:

“Proponents of sex education try to encourage our children to adopt a sex-with-no-strings-attached mentality, which is harmful to our children and to our society.”

Fran has committed the straw man (or straw woman) fallacy by misrepresenting Nancy’s position. Nancy’s position is not that we should encourage children to have sex, but that we should make sure that they are fully informed about sex so that if they do have sex, they go into it at least a little less blindly and are able to make better decisions.

As with other fallacies of relevance, straw man fallacies can be compelling on some level, even though they are irrelevant. It may be that part of the reason we are taken in by straw man fallacies is that humans are prone to “demonize” the “other”—including those who hold a moral or political position different from our own.

This tendency to “demonize the other” dovetails well with other errors of reasoning, such as the whole range of ad hominem strategies. If we are prone to demonize people who are different from us, we are ready and eager to believe that they must hold extreme views or morally outrageous beliefs. Poor reasoning breeds ever more poor reasoning. It becomes easy to think bad things about those with whom we do not regularly interact. And it is easy to forget that people who are different than us are still people just like us in all the important respects—especially in their ability to offer quality arguments.

Appeal to Consequences

Logic encourages us to maintain some overarching standards. For example, our conclusions should rest on relevant beliefs that do a good job of supporting the truth of those conclusions. We should strive to meet that standard.

However, all too often we muddy this standard by forgetting that our support should be relevant to the truth of our conclusions, not simply relevant to something important to us. Many things are of consequence to us in some general way. Sometimes it is hard to distinguish what is important to us from what is relevant to the truth of a claim.

We often have things that are of personal interest to us, and because they are valued that way we tend to think they are “relevant” to all sorts of things. This slip of the mind is a failing we should avoid. The fact that something may have a beneficial consequence to us does not automatically mean it is (a) true or (b) relevant to the truth of another claim.

There are two broad ways the consequences of a belief may interest us personally:

- Positive ways: because it benefits us

- Negative ways: because we would rather avoid it

Simply put, we are attracted to desirable things, and we are averse to painful or frightening things. This is the human condition, but it often has little to do with the truth of specific claims.

We’ll first look at the broadest form of Appeal to Consequences arguments. Then we will look at three specific ways this strategic error plays out in its positive and negative manners.

The Appeal to Consequences fallacy consists of the mistake of trying to assess the truth or reasonableness of an idea based on the (typically negative) consequences of accepting that idea.

For example, suppose that the results of a study revealed that there are IQ differences between different races (this is a fictitious example; there is no such study that I know of). In debating the results of this study, one researcher claims:

If we were to accept these results, it would lead to increased racism in our society, which is not tolerable. Therefore, these results must not be right, since if they were accepted, it would lead to increased racism.

The researcher who responds in this way has committed the Appeal to Consequences fallacy. Again, we must assess the study on its own merits. If there is something wrong with the study, some flaw in its design, for example, then that would be a relevant criticism of the study. However, the fact that the results of the study, if widely circulated, would have a negative effect on society is not a reason for rejecting these results as false. The consequences of some idea (good or bad) are irrelevant to the truth or reasonableness of that idea.

Note that in our example the researchers, being convinced of the negative consequences of the study on society, might rationally choose not to publish the study (for fear of the negative consequences). This is totally fine and is not a fallacy (we often see this kind of argument made in public health decisions, where the impact on public behavior is central to their conclusions). The fallacy consists not in choosing not to publish something that could have adverse consequences, but in claiming that the results themselves are undermined by the negative consequences they could have.

This just goes to show that the consequences of an idea are irrelevant to the truth or reasonableness of an idea. Now we will look at three unique spins on this general error, starting with two variants that stress positive consequences.

Appeal to Desire

When we have a positive view of something, we tend to want whatever is around it too. This is because we associate those things with the main thing we think is positive in the first place. Think of all the ads with sexy models shilling for cars or beers or whatever. What does sexiness have to do with how good a beer tastes? Nothing. The ads are trying to engage your emotions to get you thinking positively about their product. The strategy here is for the author of the argument to link their conclusion (e.g., “You should buy this product.”) to something beneficial for you (“You will be seen as sexy or desirable.”).

You might think that this is a pretty flat-footed approach. After all, in a calm moment of clear reflection, we can easily see that being seen as sexy has no relevance to the truth of this car’s quality, or that beer’s taste, or this vacation spot’s fun opportunities, and so forth. Yet think for a moment how often you see this done. Advertisers will spend millions on such campaigns because, as we have seen, they work.

Flat-footed or not, we are apt to be duped by these strategies when they are used without being in our faces about it. We see the ads make explicit claims that do not reference sexiness, or wealth, or whatever else they are displaying in the background. The Appeal to Desire strategy is most effective on us when we merely sniff it in the atmosphere of an argument. This makes thinking explicitly about it difficult, because it is not at the front of our consciousness.

Another way to pull this off is to link the conclusion to things that comfort us. The nefarious author is apt to use things they know we identify with (or things that are familiar to us) to make the conclusion more appealing. I might have fond memories of momma’s home cooking, but it is unlikely that this box of powdered mashed potatoes really does taste like that. I might be nostalgic about a fictional time in U.S. history when “Americans settled the Wild West,” but it is unlikely that buying this work shirt will bring me closer to becoming the rugged individual those stories promoted.

Bandwagon (a.k.a. Appeal to the People)

Another positive variant of the Appeal to Consequences fallacy uses base desires that are deeply rooted in our social nature. An extremely common technique, especially for advertisers, is to appeal to people’s underlying desire to fit in, to be hip to what everybody else is doing, to not miss out. This is the bandwagon appeal.

Think of how many times you have seen an advertisement that assures us that a certain television show is #1 in the ratings—with the tacit conclusion being that we should be watching, too. But this is a fallacy. We’ve all known it’s a fallacy since we were little kids: the first time we did something wrong because all of our friends were doing it, too, and our moms asked us, “If all of your friends jumped off a bridge, would you do that too?” Still, now we want to watch that show…the strategy still works on us.

Note that the nefarious author who uses a bandwagon strategy is relying on a powerful psychological need they know their audience harbors. Humans are social animals. We want to feel a sense of belonging to some group. We desire to fit in and are averse to feeling like we don’t belong.

We all likely remember our early teen years when it was extremely important to us that we belonged to some group in school. We did not all want to be one of the popular kids, but we all wanted to have some sense of shared identity. Perhaps we found it in a small group of “outsiders.” We may have been “misfits” to the broader community, but within our group it was important that we fit in.

So, the group doesn’t always have to be a large group—it could be an exclusive group, just so long as it is a group we find value in. Expressing positive value in group membership can be subtle. The nefarious author doesn’t have to come out and say, “this group is great!” They just have to trigger the audience to keep in mind that they are (or want to be) part of a group. Make no mistake, a simple reminder that “everyone is watching this” is enough to get the job done. After all, “everyone” is a good group—it’s big, it’s safe, and it has the appeal of common sense. The “must-see show of the season” triggers the sense that this is what everyone is watching, and that’s exactly the message the nefarious author needs us to hear. We will conclude that we too should be watching this show, because somewhere in the back of our head it makes sense to fit in. The “must-see” phrase helps us understand that the broader social group expects this of us.

Worth noting is an advertiser’s favorite tactic of using small elite groups to hock their wares. We may not want to be like everyone else. Many of us favor the idea that we do not fit in with the crowd—because we are special and unique and authentic people…so we’ll buy the leather jacket only the fashionistas appreciate (never mind that it is overpriced and was made with exploited labor). We will also show our belonging with elite groups by buying from those who have cultivated their brand as elite. The luxury car we drive is “good” because wealthy people drive it too (never mind the poor reliability scores or low customer satisfaction ratings). We want to be seen as one of them. We are still jumping on a bandwagon; it just happens to be a small one.

Appeals to hypermasculinity or toughness offer the same opportunity to identify as a rare breed. “It’s a Jeep thing—if you have to ask, you wouldn’t understand.” After all, only the rough and rugged understand the true value of how the adventurous live. For the nefarious author this has the double benefit of shielding them from critique. My conclusions are legitimate because they are the conclusions of this group, AND anyone who offers counterclaims cannot do so sensibly without betraying their non-membership with the group.

Of course, let’s not forget that we all have strong interests in belonging to multiple groups. So nefarious authors (in this case, advertisers) often use overlapping groups to promote the tacit conclusions of their ads (buy this product). When a celebrity like John Travolta wears a watch as he walks towards his jet aircraft, we want that watch! He’s sexy, he’s rich, he’s adventurous, and he’s famous. So if you can break into that crowd, then you know you’ve made it too. The watch is way too big for your wrist, but no matter. You still want it.

Appeal to Force

A negative variant of the Appeal to Consequences uses our fear of bad things to get us to accept the truth of some claims. In this fallacy the nefarious author attempts to convince their audience to believe something by threatening them. Threats pretty clearly distract one from the business of dispassionately appraising premises’ support for conclusions, so it’s natural to classify this technique broadly as an Error of Relevance.

There are many examples of this technique throughout history. In totalitarian regimes, there are often severe consequences for those who don’t toe the party line (see George Orwell’s 1984 for a vivid, though fictional, depiction of the phenomenon). The Catholic Church used this technique during the infamous Spanish Inquisition: the goal was to get non-believers to accept Christianity; the method was to torture them until they did.

While these examples suggest that the Appeal to Force strategy is always heavy-handed, most instances are actually quite subtle. The trouble is that people generally don’t like being threatened. So, when they are directly threatened, unless that threat is both believable and extreme, they are likely to reject the strategy used on them. Simply put, we resist. For the nefarious author, this is not a good tactic. Better for them to use a subtle tactic to pull off this strategy.

For example, your boss seems concerned about you. I mean, after all, you’re up for review soon and maybe your promotion or even position in the job is on the line. “I just want to make sure you’re going to be in good shape with the company. We’d hate to have to lose you. Let’s talk about that triple-overtime I told you about yesterday.”

Note that the boss isn’t outright threatening you. Indeed, your boss uses passive language. She won’t fire you—“we’d have to lose you,” as though it just might be a thing that happens. She is concerned; she is worried for your well-being. That’s the official message uttered out loud. But not really. The subtle message is quite the opposite. Real-world appeals to force are often done within contexts that establish the threat.

Appeal to Force strategies are often done with sympathetic words. A nefarious author may appear to want what is good for you. Consider the tone of voice used when people say things like this:

“I just couldn’t bear the thought of what would happen to you if you left me. I love you more than anything else in the world.”

“Accepting this religious claim is your only salvation, your only hope to truly find the peace you are looking for. Without it your eternal soul will be lost.”

“I need to know you’ll be safe and able to stand on your own two feet. You have to major in finance or pharmacy. We can’t keep paying for you to throw your life away on this poetry thing. Your future is all we care about.”

Most folks who offer arguments like this sound nice. At least, they seem deeply concerned with our well-being. However, the quality of this relationship and my decision to stay in it should be determined by how I might see the relationship, not the consequences of what my partner will do (to me) if I should leave. Likewise, our well-being doesn’t make those religious claims true—what might happen to me if I don’t accept those claims offers no support for the truth of those claims. Last, as caring as my parents might come across, their threat to withhold financial support for my schooling is not relevant to whether it is true that I should select this or that major. These are all just sugar-coated threats.

Last, when we look at the conclusions of these arguments, we can see, at least in principle, that there are relevant reasons to accept them—an author could have spoken directly to the truth of those claims and given us direct reasons to accept them. However, they opted instead not to address them. They could have spoken to why this relationship is worth salvaging, or why the beliefs of this religious tradition are true, or why these majors make sense for us to pursue. None of these were mentioned. Instead they made assorted threats about the consequences we would face if we didn’t accept their conclusions.

Appeal to Pity

Another emotional response we are likely to have is pity for others. This is generally a good thing, but as we have seen, a nefarious author can take advantage of their audience by using this to convince them to accept a conclusion without proper support. Consider this example:

But Professor, I tried really hard on the exam. I need this class to graduate. If I don’t pass, I’m going to be held back. I worked my fingers to the bone! You just have to pass me.

Note how the error of reasoning here relies heavily on the nature of the appeal. This strategy involves appealing to the pity itself as the support for the truth of a conclusion. This is irrelevant.

Of course, there are relevant reasons a professor should pass a student—such as strong performance on the exams, completion of assignments to a satisfactory level, and attendance and participation in class (if this is part of the course’s grading structure). However, this author avoids bringing these up. Instead, they invoke their effort, their graduation requirements, and their academic progress. All of these are irrelevant to the truth of whether or not they earned a passing grade. So why bring it up? Answer: to make the professor feel pity for the author. This nefarious strategy is simple: You should accept my conclusion because you feel bad for me.

The recursive nature of the appeal is important. If an argument is made and the claims within it happen to make the audience feel bad for some third party, this is not an appeal to pity strategy. We only use the audience’s pity-response to identify a nefarious strategy when:

- That response was the whole point of raising these claims (i.e., it was the author’s intention to invoke pity)

- The substance of what invokes pity is irrelevant to the truth of the conclusion

- The pity is intended for the author of the argument (i.e., it is recursive)

So consider the following commercial:

For some dogs, Christmas is a terrible time. Left out in the cold, these poor souls have no hope. They suffer in the cold, underfed and unloved. For just $9.99 you can help those who cannot help themselves. Won’t you consider supporting our work to rescue these animals?

These sorts of commercials almost always show miserable dogs kept in the cruelest conditions. What sort of person would see this and not feel some pity for those animals? We can expect that most audience members would feel bad for the dogs. Yet we should not jump the gun and claim we are being manipulated by a nefarious author who is trying to dupe us. After all, the conclusion is that we should help the dogs (or help the organization whose work is to help the dogs). If the dogs were supremely trained actors and they were not really in dire straits, then we would feel duped. We would feel this way precisely because their miserable condition is actually relevant to the conclusion that we should help alleviate that condition. We’re being presented with the images/claims of their suffering because the substance of their suffering is relevant to the conclusion. This removes condition (b) above.

Now consider condition (c) above: is the intent of the commercial to make you feel bad for the organization asking for your help? No. The organization (as the author of the argument) does not want you to feel pity for them. There’s a third party in this argument (the dogs), and the author’s premises suggest cause for feeling bad about those others who are in a bad situation. So condition (c) is not met.

We might be concerned about the commercial’s intention; that is, condition (a) above may still apply. So ask yourself, is the whole point of the images/claims just to make us feel pity? This is a bit tricky to evaluate. When you hear the music played, the tone of the announcer, the terrible images, you certainly think: if nothing else, they are trying pretty hard to make you to feel pity for the dogs. So there is something there. However, without condition (b) making the substance of the dogs’ condition irrelevant, we might charitably say the author has little chance of avoiding invoking pity. I suppose they could not tell you about the dogs, but that wouldn’t help establish any conclusion to help the dogs. So that seems unreasonable. What’s not unreasonable is that they could have left out the sad, desperate music, and they could have conveyed their message without the anguished tone of voice. At the very least, we can temper our concerns by noting that condition (c) is also not met. The pity is almost inevitable (thus, not directly appealed to) and there is no effort to appeal to the pity on behalf of the author. Put differently, some commercials are troubling (from a logical point of view), but they are not outright nefarious.

Red Herring / Avoiding the Issue / Evasion

This fallacy initially gets its name from the actual fish. When herring are smoked, they turn red and are quite pungent. Stinky things can be used to distract hunting dogs, who of course follow the trail of their quarry by scent; if you pass over that trail with a stinky fish and run off in a different direction, the hound may be distracted and follow the wrong trail.

Whether or not this practice was ever used to train hunting dogs, as some suppose, the connection to logic and argumentation is clear. One commits the red herring fallacy when one attempts to distract one’s audience from the main thread of an argument, taking things off in a different direction. The diversion is often subtle, with the detour starting on a topic closely related to the original—but gradually wandering off into unrelated territory.

The tactic is also often (but not always) intentional: one commits the red herring fallacy because one is not comfortable arguing about a particular topic on its merits, often because the author knows their own case is weak; so instead, the arguer changes the subject to an issue about which he feels more confident, makes strong points on the new topic, and pretends to have won the original argument. They have effectively avoided the original issue or evaded the criticisms of their stance.

Note that people often offer red herring arguments unintentionally, without the deceptive motivation to change the subject. Sometimes a person’s response will be off topic, apparently because they were confused for some reason. Such cases are usually easily resolved when the audience points this out. When unintentional, the strategy of a red herring is abandoned quickly because the non-nefarious author does not really want to use such a poor strategy, but realizes that this is what they are doing. In the intentional cases, this is not so. The author is much more likely to resist the claim that they are off topic because they know they are relying on that strategy to make their case.

People may also be unaware that they are using this strategy even when they are intentionally using tactics that produce it. That is, many people believe they should bring up certain points (and so, they do it on purpose) simply because a certain topic has been raised. Two points are important here:

- They won’t admit that they are trying to evade the specific subject of an argument (because they are not aware that they have missed the point[1]).

- However, they are perfectly aware that they are bringing in a new topic to the discussion or debate (they simply feel it is appropriate to do so).

These “Well what about…” insertions are common when people feel their own beliefs are challenged (especially around political affiliation and moral accusations). For example:

Caroline may be upset at her husband’s wandering eye lately and calls him out on it. Manny instinctively (and thus, unintentionally) responds, “Well, what about you? You dated plenty of guys in your time before we got married!”

Manny may not realize he is getting off track (his own behavior is at stake, and it is this current conduct that is central to the accusation). Yet he is very aware that he is letting his wife know he expects this topic to be brought into the conversation. The tactic is intentional; the broader strategy is not.

What-about-isms are convenient ways to hide the shortcomings of one’s own position as well as remain oblivious to the irrelevance of what one wants to introduce into the argument. This is often accomplished in the name of an important principle: don’t be a hypocrite. In this example, Manny expects his wife to follow this principle. So, he feels entitled to introduce her own behavior—as that appears to him to be relevant to the accusation she levied against him. While it is generally a good principle to follow, it belongs in a different argument. If there is something wrong with Caroline’s current or past behavior, this judgment stands on its own and has no bearing on whether or not Manny’s behavior today is morally culpable. These would be best addressed in two different arguments (as would the third argument regarding the accusation that Caroline is hypocritical in her expectations of her husband).

What-about-isms are powerfully effective because they directly challenge the audience to consider a new claim. The audience needs to be clear-minded to identify the irrelevancy and steadfast to remain on topic. This is difficult to do in heated debate, such as we find in political discussions. For example:

At the neighborhood Halloween party, Rob’s liberal-leaning neighbor, Linda, may show dismay at his support of Donald Trump. Linda might ask (and might even ask with genuine curiosity or wonder), “How could you support a guy who treats women the way he does?” To which Rob remarks, “Well what about Clinton? Ol’ Bill was having sex in the Oval Office!”

This might seem like a fair application of the hypocrite principle, except that Bill Clinton’s behavior is not the subject of the inquiry. Clinton isn’t running against Trump—thus, his conduct is irrelevant. Additionally, if pressed, Linda may express her disgust at Clinton’s behavior as well—thus defusing the alleged hypocrisy. However, what-about-isms help a nefarious author feel better about their insertion, as though they have taken the moral high ground (or at least, they have not ended up in a moral underground).

Politicians use the general version of the red herring fallacy all the time. Consider a debate about Social Security—a retirement stipend paid to all workers by the federal government. Suppose a politician makes the following argument:

We need to cut Social Security benefits, raise the retirement age, or both. As the baby boom generation reaches retirement age, the amount of money set aside for their benefits will not be enough cover them while ensuring the same standard of living for future generations when they retire. The status quo will put enormous strains on the federal budget going forward, and we are already dealing with large, economically dangerous budget deficits now. We must reform Social Security.

Now imagine an opponent of the proposed reforms offering the following reply:

Social Security is a sacred trust, instituted during the Great Depression by FDR to ensure that no hard-working American would have to spend their retirement years in poverty. I stand by that principle. Every citizen deserves a dignified retirement. Social Security is a more important part of that than ever these days, since the downturn in the stock market has left many retirees with very little investment income to supplement government support.

The second speaker makes some good points, but notice that they do not speak to the assertion made by the first: Social Security is economically unsustainable in its current form. It’s possible to address that point head on, either by making the case that in fact the economic problems are exaggerated or nonexistent, or by making the case that a tax increase could fix the problems. The respondent does neither of those things, though; he changes the subject, and talks about the importance of dignity in retirement. He’s likely more comfortable talking about that subject than the economic questions raised by the first speaker, but it’s a distraction from that issue—a red herring.

Perhaps the most blatant kind of red herring is evasive: used especially by politicians, this is the refusal to answer a direct question by changing the subject. Examples are almost too numerous to cite; to some degree, no politician ever answers difficult questions straightforwardly (there’s an old axiom in politics, put nicely by Robert McNamara: “Never answer the question that is asked of you. Answer the question that you wish had been asked of you.”).

A particularly egregious example of this occurred in 2009 on CNN’s Larry King Live. Michele Bachmann, Republican Congresswoman from Minnesota, was the guest. The topic was “birtherism,” the (false) belief among some that Barack Obama was not born in America and was therefore not constitutionally eligible for the presidency. After playing a clip of Senator Lindsey Graham (R, South Carolina) denouncing the myth and those who spread it, King asked Bachmann whether she agreed with Senator Graham. She responded thus:

“You know, it’s so interesting, this whole birther issue hasn’t even been one that’s ever been brought up to me by my constituents. They continually ask me, where’s the jobs? That’s what they want to know, where are the jobs?”

Bachmann doesn’t want to respond directly to the question. If she outright declares that the “birthers” are right, she looks crazy for endorsing a clearly false belief. But if she denounces them, she alienates a lot of her potential voters who believe the falsehood. Tough bind. So she blatantly, and rather desperately, tries to change the subject. Jobs! Let’s talk about those instead.

There is a special variant of the Red Herring fallacy that bears recognition: the smokescreen. Smokescreen strategies attempt to distract and divert the audience’s attention away from the topic or inquiry at hand by way of a barrage of information that appears relevant to the topic. To the nefarious author, this has the added advantage of making them look thoughtful and well-informed. They seek to overwhelm their audience with important information that the audience is not ready to process. Along the way the discussion is tilted in a direction more favorable to the nefarious author.

Again, politicians provide some of the best examples. This is often because many of them are former lawyers who are well-versed in a complex legal system that touts highly technical language. Consider the following example:

In a legal debate over proposed legislation to address police reform and accountability, a politician is asked about their position. Instead of directly addressing the question, the politician launches into a lengthy discourse about the intricacies of constitutional law, citing obscure legal precedents related to federalism and states’ rights, and the historic difficulty of civilian oversight boards with subpoena powers. They employ convoluted legal jargon and complex terminology, effectively creating a smokescreen of legal complexity to obfuscate the straightforward issue of police accountability.

In this scenario, the politician uses a smokescreen fallacy by inundating the discussion with dense legal language, making it difficult for the audience to follow and diverting attention away from the core issue of police reform. This can be a delay tactic, or it can be used to soften an unpopular decision to do nothing and keep the status quo.

SET II

Appeals to Unwarranted Assumption

The fallacies in this group all share a common strategy in which the author of the argument makes use of a premise that they are unauthorized to use. We call these claims “unwarranted” to highlight the nature of the error.

Before we go further, we should first clarify the role of assumptions. Recall that an argument’s basic structure is that of a set of statements, some of which are intended to support another.

This basic structure reveals that in its most raw form, the premises of an argument are put forth unsupported. Their job is to support the truth of the conclusion, but in the first instance they themselves have no direct support in the argument.

One way to think of this is that the premises are all assumed to be true (by the author). If the audience challenges one or more of them, they will need to form a sub-argument to support the truth of the premise under attack, but initially this is not the intent. Make no mistake, we count on assumptions in every argument. We also count on assumptions in daily life. This is unavoidable, and often there is nothing wrong with relying on an assumption.

The common quality of this group of fallacies is NOT that they involve assumptions. The common quality is that they involve assumptions that the author has no rightful claim to make. They help themselves to a claim that they are not entitled to make. Put differently, it is the “unwarranted” part of the assumption that is the source of the error, not the simple fact that an assumption was made.

Begging the Question

Begging the question occurs when one (either explicitly or implicitly) assumes the truth of the conclusion in one or more of the premises. Begging the question is thus a kind of circular reasoning.

Consider the following argument:

Capital punishment is justified for crimes such as rape and murder because it is quite legitimate and appropriate for the state to put to death someone who has committed such heinous and inhuman acts.

The premise indicator, “because,” denotes the premise and (derivatively) the conclusion of this argument. In standard form, the argument is this:

-

- It is legitimate and appropriate for the state to put to death someone who commits rape or murder.

Therefore, capital punishment is justified for crimes such as rape and murder.

You should notice something peculiar about this argument: the premise is essentially the same claim as the conclusion. The only difference is that the premise spells out what capital punishment means (the state putting criminals to death), whereas the conclusion just refers to capital punishment by name, and the premise uses terms like “legitimate” and “appropriate,” whereas the conclusion uses a related term, “justified.” But these differences don’t add up to any real differences in meaning. Thus, the premise is essentially saying the same thing as the conclusion.

This is a serious failing of an argument: we want our premise to provide a reason to accept the conclusion. But if the premise is the same claim as the conclusion, then it can’t possibly provide a reason for accepting the conclusion!

One interesting feature of this fallacy is that formally there is nothing wrong with arguments of this form. Here is what I mean. Consider an argument that explicitly commits the fallacy of begging the question. For example,

- Capital punishment is morally permissible

- Therefore, capital punishment is morally permissible

Now, apply any method of assessing validity to this argument and you will see that it is valid. If we use the informal test (by trying to imagine that the premises are true while the conclusion is false), then the argument passes the test, since any time the premise is true, the conclusion will have to be true as well (since it is the exact same statement).

While these arguments are technically valid, they are still really bad arguments. Why? Because the point of giving an argument in the first place is to provide some reason for thinking the conclusion is true for those who don’t already accept the conclusion. But if one doesn’t already accept the conclusion, then simply restating the conclusion in a different way isn’t going to convince them. Rather, a good argument will provide some reason for accepting the conclusion that is sufficiently independent of the conclusion itself. Begging the question utterly fails to do this, and this is why it counts as an informal fallacy. What is interesting about begging the question is that there is absolutely nothing wrong with the argument formally.

Whether or not an argument begs the question is not always an easy matter to sort out. As with all informal fallacies, detecting it requires a careful understanding of the meaning of the statements involved in the argument and what the author is doing with them. Here is an example of an argument where it is not as clear whether there is a fallacy of begging the question:

Christian belief is warranted because, according to Christianity, there exists a being called “the Holy Spirit,” which reliably guides Christians towards the truth regarding the central claims of Christianity.[2]

One might think that there is a kind of circularity (or begging the question) involved in this argument, since the argument appears to assume the truth of Christianity in justifying the claim that Christianity is true. But whether this argument really does beg the question often rests on what the author actually means in their statements. Consider the term “warranted” in the above argument. There are at least two common ways to interpret this: as “understandable” or as “justified.” Let’s consider each in turn.

If the author means something like “understandable,” then the argument clearly does not beg the question. After all, if the author wants you to believe that “It is understandable for Christians to adhere to the core tenets of their faith,” then it is helpful to learn (in the premise) that they take these beliefs to come from a divine source. Now the audience has reason to believe in the truth of what the conclusion asserts: These beliefs are not “crazy” or “superstitious,” but rather part of a sensible worldview in which beliefs should only derive from reliable sources.

However, consider if the term “warranted” means “justified” to the author. The argument becomes circular. This is because the conclusion is “Christian beliefs are justified” and the support is “Christian beliefs say their beliefs are justified.” Now the audience has no reason to accept the truth of the conclusion unless they already accept the substance of the conclusion.

Inappropriate Authority

In a society like ours, we have to rely on authorities to get on in life. For example, the things I believe about electrons are not things that I have ever verified for myself. Rather, I have to rely on the testimony and authority of physicists to tell me what electrons are like. Likewise, when there is something wrong with my car, I have to rely on a mechanic (since I lack that expertise) to tell me what is wrong with it. Such is modern life. So there is nothing wrong with needing to rely on authority figures in certain fields (people with the relevant expertise in that field)—it is inescapable. The problem comes when we invoke someone whose expertise is not relevant to the issue for which we are invoking it. For example:

Bob read that a group of doctors signed a petition to prohibit abortions, claiming that abortions are morally wrong. Bob cites the fact that these doctors are against abortion, “See, even the people who know how it’s done think it is wrong. Who else better to say? Abortion must be morally wrong.”

Bob has committed the Appeal to Authority fallacy. The problem is that doctors are not authorities on what is morally right or wrong. Even if they are authorities on how the body works and how to perform certain procedures (such as abortion), it doesn’t follow that they are authorities on whether or not these procedures should be performed—the ethical status of these procedures. It would be just as much an Appeal to Inappropriate Authority fallacy if Melissa were to argue that since some other group of doctors supported abortion, that shows that it must be morally acceptable. In either case (for or against), doctors are not authorities on moral issues, so their opinions on moral issues like abortion are irrelevant.

In general, an Appeal to Inappropriate Authority fallacy occurs when an author takes what an individual says as evidence for some claim, when that individual has no particular expertise in the relevant domain. This can be innocently done, especially when the source cited does have expertise in some other unrelated domain.

This is a favorite technique of advertisers. We’ve all seen celebrity endorsements of various products. Sometimes the celebrities are appropriate authorities. For example, there was a Buick commercial from 2012 featuring Shaquille O’Neal, the Hall of Fame basketball player, testifying to the roominess of the car’s interior (despite its compact size). Shaq, a very, very large man, is an appropriate authority on the roominess of cars! But when Tiger Woods was the spokesperson for Buicks a few years earlier, it wasn’t at all clear that he had any expertise to offer about their merits relative to other cars. Woods was an inappropriate authority; those ads committed the fallacy.

Usually, the inappropriateness of the authority being appealed to is obvious. But sometimes it isn’t. A particularly subtle example is AstraZeneca’s hiring of Dr. Phil McGraw in 2016 as a spokesperson for their diabetes outreach campaign. AstraZeneca is a drug manufacturing company. They make a diabetes drug called Bydureon. The aim of the outreach campaign, ostensibly, is to increase awareness among the public about diabetes, but of course the real aim is to sell more Bydureon. A celebrity like Dr. Phil can help. Q: Is he an appropriate authority? That’s a hard question to answer. It’s true that Dr. Phil had suffered from diabetes himself for 25 years, and that he personally takes the medication. So that’s a mark in his favor, authority-wise. But is that enough? (HINT: No. It is not enough. We’ll talk about how feeble Phil’s sort of anecdotal evidence is in supporting claims about a drug’s effectiveness when we discuss the hasty generalization fallacy. Suffice it to say, one person’s positive experience doesn’t prove that the drug is effective.)

You might be tempted to say,

“But Dr. Phil isn’t just a person who suffers from diabetes; he’s a doctor! It’s right there in his name. Surely that makes him an appropriate authority on the question of drug effectiveness.”

This may sound appropriate, but Phil McGraw is not a medical doctor; he’s a PhD (the “D” in PhD stands for “doctor of”). He has a doctorate in psychology. He’s not even a licensed psychiatrist; he cannot legally prescribe medication. He has no relevant professional expertise about drugs and their effectiveness (especially with regard to diabetes). He is not an appropriate authority in this case. He looks like one, though, which makes this a very sneaky, but effective, advertising campaign.

False Dilemma / False Dichotomy

Suppose I were to argue as follows:

- Raising taxes on the wealthy will either hurt the economy or help it.

- But it won’t help the economy.

Therefore, it will hurt the economy.

This argument contains a fallacy called a False Dilemma or “false dichotomy.” A false dichotomy is simply a disjunction that does not exhaust all of the possible options. In this case, the problematic disjunction is the first premise: either raising the taxes on the wealthy will hurt the economy or it will help it. But these aren’t the only options. Another option is that raising taxes on the wealthy will have no effect on the economy.

If we fail to see that the nefarious author has presented us with a false choice, we may evaluate the argument on its formal merits. If so, we’ll note that it is a formally valid argument. However, since the first premise presents two options as if they were the only two options, when in fact they aren’t, the first premise is false and the argument fails. This failure is due to its content, not its form. In this case, there is something more than merely a false premise. There is an active strategy to hide and/or limit the options from the audience. Additionally, the nefarious author’s strategy will often disproportionately characterize one option in a negative light. The intent is to push the audience into the option that constitutes the nefarious author’s conclusion. You feel like you are backed into a corner and have no other choice than to accept the author’s conclusion.

Consider the following example. In a speech made on April 5, 2004, President Bush made the following remarks about the causes of the Iraq war:

Saddam Hussein once again defied the demands of the world. And so, I had a choice: Do I take the word of a madman, do I trust a person who had used weapons of mass destruction on his own people, plus people in the neighborhood, or do I take the steps necessary to defend the country? Given that choice, I will defend America every time.

The False Dilemma here is the claim that: Either I trust the word of a madman or I defend America (by going to war against Saddam Hussein’s regime). The problem is that these aren’t the only options. Other options include ongoing diplomacy and economic sanctions—options which the holder of the highest political office in the land would have been clearly aware were on the table. Thus, even if it were true that Bush shouldn’t have trusted the word of Hussein, it doesn’t follow that the only other option was going to war against Hussein’s regime. (Furthermore, it isn’t clear why this was needed to defend America.) That is a false dichotomy.

Care should be taken when assessing an argument as a False Dilemma. The error of this fallacy lies in the falseness of the proposed “choice” between the two options. This is a strategic move made by a nefarious author. However, if the world is such that there really are only two options, we cannot lay blame on the world for limiting our choices to two. Consider the following:

Shortly after the Titanic hits the iceberg, Leo tells Kate, “There’s one last spot left. Get in the lifeboat without me or you’re going to die!”

Also: