Chapter 3 – Amendment I: Exploring Freedoms, Rights, Privileges & Their Differences

Amendment I

Richard J. Forst and Tauya R. Forst

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

3.1 Identify the unfamiliar terms of the First Amendment.

3.2 Explain the three freedoms guaranteed by the First Amendment.

3.3 Summarize the two rights defined in the First Amendment.

3.4 Compare the difference between a freedom and a right.

3.5 Demonstrate examples of how the freedom and rights of the First Amendment apply to case law.

KEY TERMS

| Abridge | Petition |

| Assemble | Political Expression |

| Assembly | Prior Restraint |

| Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission | Press |

| Constitutional Freedom/Freedom | Redress |

| Constitutional Rights/Rights | Religion |

| Establishment Clause | Right |

| Free Exercise Clause | Symbolic Speech |

| Grievance | Unlawful Assembly |

| Peaceably | Verbal (Pure) Speech |

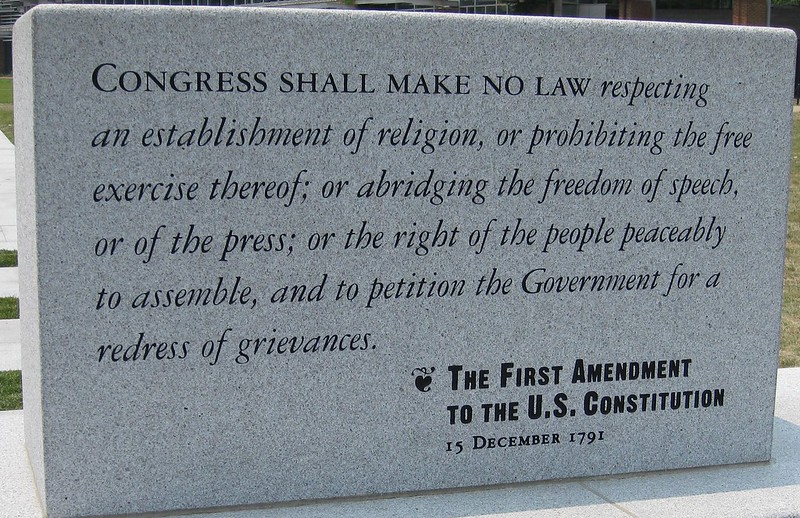

Amendment I

Passed by Congress September 25, 1789. Ratified December 15, 1791. The first 10 amendments form the Bill of Rights.

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

Understanding the Amendments

To fully understand the United States Constitution, we use a process which helps identify and distinguish components of the writings. First, we must determine how many parts (different rights and freedoms) exist in the First Amendment. This will require a literal reading of each part of the amendment. Next, we determine the parts. This allows us to understand the verbiage of the United States Constitution. Words matter. Lastly, we use these important words to identify from where these concepts originate. Let’s get started.

INTRODUCTION TO AMENDMENT I

The original Constitution were completed as an exercise in compromise in 1776. The original Constitution is comprised of the Preamble and the Seven Articles. The Framers maintained a healthy appetite for change as they created Article V of the United States Constitution, recognizing the need for amendments. The Framers balanced the need for amendments with a high standard of achievement. Note: The First Amendment does not apply to private entities or persons. The First Amendment outlines governmental restrictions – federal, state, and local. The first 10 amendments together are dubbed the Bill of Rights – all ratified on the same date – December 15, 1791; however, the name might be contradictory in nature.

Similar to the other amendments of the Bill of Rights, Amendment I originally pertained to the actions of the federal government, without addressing actions by the states. However, state constitutions (as adopted by each state) have their own versions of the Bill of Rights which parallel the United States Bill of Rights.[1] Unfortunately, these provisions were enforceable only in their own state courts. To this end, when the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified in 1868, the United States Constitution set forth prohibitions for the states which included preservation of such rights as liberty and due process. According to Britannica, the Supreme Court of the United States has slowly used the Fourteenth Amendment Due Process clause to apply most of the first 10 amendments (including Amendment I clauses) to state governments. In this instance, the clauses of Amendment I cover all governments (federal, state, and local) and all branches (legislative, executive, and judicial) as well as public employers and schools.[2]

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

“Madison’s version of the speech and press clauses, introduced in the House of Representatives on June 8, 1789, provided: The people shall not be deprived or abridged of their right to speak, to write, or to publish their sentiments; and the freedom of the press, as one of the great bulwarks of liberty, shall be inviolable.

The special committee rewrote the language to some extent, adding other provisions from Madison’s draft, to make it read: The freedom of speech and of the press, and the right of the people peaceably to assemble and consult for their common good, and to apply to the government for redress of grievances, shall not be infringed.

In this form it went to the Senate, which rewrote it to read: That Congress shall make no law abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press, or the right of the people peaceably to assemble and consult for their common good, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

Subsequently, the religion clauses and these clauses were combined by the Senate. The final language was agreed upon in conference.”[3]

As the Framers engaged in negotiating the verbiage of the amendment, they considered the context and framework for both constitutional freedoms and rights. Freedom or constitutional freedom are defined as “[a] basic liberty guaranteed by the Constitution or Bill of Rights, such as the freedom of speech.”[4] Whereas right or constitutional right are defined as “[s}omething that is due to a person by just claim, legal guarantee, or moral principle”[5] “guaranteed by a constitution; [especially], one guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution or by a state constitution.”[6] It is important to understand how the term “right” was used, not as we understand it today, but how the Framers would have regarded this term. Today, we speak of personal and individual rights, such as our fundamental right to keep and bear arms.

However, Campbell noted the Framers categorized rights into two categories – natural rights and positive rights.[7] Campbell further warned that this framework is essential to the discussion when he stated, “[u]nless we approach the task of Constitutional interpretation on their terms rather than on ours, the First Amendment’s original meaning will remain elusive.”[8] Simply, natural rights are things which can be accomplished without governmental intervention such as eating, walking, and thinking.[9] Whereas, positive rights are those things which center on governmental authority such as right to jury trial.[10] It is with this analysis in mind that one should read the remainder of this chapter, the textbook, and consider the balance of the rights found in the United States Constitution.

Five Parts of the First Amendment

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT I

Part I – Freedom of Religion

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion

Thomas Jefferson Writings, 3rd United States President[11]

a. Establishment Clause

The right to choose how to express faith and worship includes expressing no religion. Individuals are allowed to practice or abstain from practicing religious beliefs, without governmental interference or promotion of religion. Religion is defined as

“[a} system of faith and worship [usually] involving belief in a supreme being and [usually] containing a moral or ethical code; [especially], such a system recognized and practiced by a particular church, sect, or denomination. In construing the protections under the Establishment Clause and the Free Exercise Clause, courts have interpreted the term religion broadly to include a wide variety of theistic and nontheistic beliefs.”[12]

This right was also guaranteed by the United States Constitution Article VI, §3 and was discussed earlier in Chapter 2.“Madison’s original proposal for a bill of rights provision concerning religion read: The civil rights of none shall be abridged on account of religious belief or worship, nor shall any national religion be established, nor shall the full and equal rights of conscience be in any manner, or on any pretence, infringed. The language was altered in the House to read: Congress shall make no law establishing religion, or to prevent the free exercise thereof, or to infringe the rights of conscience. In the Senate, the section adopted read: Congress shall make no law establishing articles of faith, or a mode of worship, or prohibiting the free exercise of religion. . . . It was in the conference committee of the two bodies, chaired by Madison, that the present language was written with its somewhat more indefinite respecting phraseology. Debate in Congress lends little assistance in interpreting the religion clauses; Madison’s position, as well as that of Jefferson, who influenced him, is fairly clear, but the intent, insofar as there was one, of the others in Congress who voted for the language and those in the states who voted to ratify is subject to speculation.”[13]

The Establishment Clause is misquoted typically. As a point of reference, the Establishment Clause is defined as “[t]he First Amendment provision that prohibits the federal and state governments from establishing an official religion, or from favoring or disfavoring one view of religion over another.”[14] Most individuals who read the First Amendment want to believe that this clause denotes unlimited access to establishing a religion. In fact, none of the freedoms or rights is absolute. The courts determined this stance early on. This clause was specific to the government and its restriction against establishing a church that all in America would be subject to. Additionally, this clause outlined the ability for most to establish a religion, unless the religion interferes with the health and safety of those on American soil. In Everson v. Board of Education (1947), the court held that the purpose of this clause was primarily to create a separation between church and state.[15] Justice Hugo Black explained in simple, yet pointed words why this clause was included in the Bill of Rights.[16] Further, Justice Black delivered a clear and concrete analysis of what the First Amendment means by addressing its application to religion and church. Justice Black emphasized that:

“a state nor the Federal Government can set up a church. Neither can pass laws which aid one religion, aid all religions, or prefer one religion over another. Neither can force nor influence a person to go to or to remain away from church against his will or force him to profess a belief or disbelief in any religion. No person can be punished for entertaining or professing religious beliefs or disbeliefs, for church attendance or non-attendance.”[17]

The Supreme Court applied the religion clauses to the states beginning with the 1940s. This application exhibited a wide interpretation of the religion clauses. Specifically in Everson v. Board of Education, with a 5-4 decision which declared that the Establishment Clause forbids not only practices that aid one religion

or prefer one religion over another,

but also those that aid all religions.

[18]

The Supreme Court addressed a scenario in which the Establishment Clause clashed with the Free Exercise Clause, “[t]he constitutional provision (U.S. Const. amend. I) prohibiting the government from interfering in people’s religious practices or forms of worship,”[19] in Kennedy v. Bremerton School District (2022).[20] Kennedy was a public high school football coach, who engaged in prayer with a number of students during and after school games. His employer, the Bremerton, Washington School District, asked that he discontinue the practice in order to protect the school for a lawsuit based on violation of the Establishment Clause. Kennedy refused, was then fired, and sued the school district.[21] By a 6-3 vote, the majority held that the Free Exercise and Free Speech Clauses of the First Amendment protect an individual engaging in a personal religious observance from government reprisal.[22] Thus the Court struck down a long-standing precedent. In Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971), the Court held that the First Amendment prohibited government from providing resources to establish religion unless there is a “legitimate secular purpose.”[23]

b. Free Exercise Clause

or prohibiting the free exercise thereof

The government gives all persons the freedom or ability to engage in religion without hindrance. Although, Free Exercise is part of the Freedom of Religion, this does not mean that it is absolute. One example of a limit on the Free Exercise clause is practicing a religion where poisonous snakes are being handled and can kill its participants. The sacred practice of snake handling began in 1909 in the Church of God, when members of its church interpreted scriptures literally.[24] The participants believed that handling poisonous snakes was integral to their worship experience. Although, the practice of snake handling has claimed many lives, the courts have refused to extend the Free Exercise protection in an effort to block the restrictions placed by the government.[25]In most instances, the government restricts this freedom through the balancing of reasonable health restrictions. A case of this magnitude has not reached the Supreme Court of the United States; however, several states have weighed in with their opinions. Tennessee, Kentucky, Connecticut, and Alabama have all identified some restriction on who can handle the poisonous creatures as well as the protocols for children who may be affected as noted in Harden v. State (1948).[26]

This balance between Free Exercise and medical treatment heightens the legal debate. Religious beliefs extend into debates regarding whether an individual receives medical treatment. Also, these beliefs are apparent as individuals examine how one receives medical treatment. This may include, but is not limited to, “Do Not Resuscitate” orders, decisions to receive organ transplants, and blood transfusions. Blood transfusions, or should we say, the denial of blood transfusions has been an important tenet for Jehovah Witnesses and other religions for years. Although individual members are allowed to deny their own blood transfusion treatment; the court has determined that this decision may not be made for a child suffering a life-threatening illness where a health expert deems blood transfusion as critical.[27] Even in a situation involving a 25-year-old woman, the federal judge ordered a transfusion against the married woman’s request.[28]

This balancing act continues to be problematic as the Court determines its interest and proper place in such a polarizing topic. Once again, the Supreme Court of the United States refuses to review a case on this topic for either adults or children. Lower courts have upheld opinions for those who want to execute Free Exercise as well as those who believe these topics violate the government’s right to restrict the Free Exercise clause for the health and well-being under the state’s purview. It is extremely important to note that: “Forty-six states have statutes that allow parents to use their religious beliefs as a defense against prosecution for withholding medical treatment from their children.”[29] One must consider other aspects of this discussion. If states allow the Free Exercise clause as a defense to the previously mentioned statutes, then obviously the states have considered whether or not these items should be crimes. A state could have determined that these actions are not punishable; thus, it appears that the government intended to have restrictions dismissing any rights to absolutism.

However, in Wisconsin v. Yoder (1972), the Supreme Court noted that “only those interests of the highest order and those not otherwise served can overbalance legitimate claims to the free exercise of religion.”[30] In 2022, the Supreme Court ruled that the State of Maine may not exclude religious schools from a state tuition program. The majority opinion in Carson v. Makin (2022), penned by Chief Justice Roberts, held that states that choose to subsidize private schools may not discriminate against religious ones.[31]

Furthermore, the Supreme Court addressed the balancing act in a 2023 decision, 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis (2023) decided by a 6-3 vote.[32] Justice Gorsuch, writing for the majority, held that the First Amendment prohibits Colorado from forcing a website designer to create expressive designs speaking messages with which the designer disagrees.[33]

In this case, a website designer wanted to expand her services to include wedding websites, but did not want to offer those websites to same-sex couples because of her religious belief that same-sex marriages are “false” and contrary to God’s design.[34] A Colorado law bars discrimination because of disability, race, creed, color, sexual orientation, gender identity, marital status, national origin or ancestry in a place of accommodation.[35] For Justice Gorsuch, the Colorado law was unconstitutionally compelling speech by the website designer.[36] In dissent, Justice Sotomayor wrote, “…if a business chooses to profit from the public market, which is established and maintained by the state, the state may require the business to abide by a legal norm of nondiscrimination.”[37]

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

“More recent decisions, however, evidence a narrower interpretation of the religion clauses. Indeed, in Employment Division, Oregon Department of Human Resources v. Smith (1990) the Court abandoned its earlier view and held that the Free Exercise Clause never relieve[s] an individual of the obligation to comply with a ‘valid and neutral law of general applicability.’

[38] On the Establishment Clause the Court has not wholly repudiated its previous holdings, but recent decisions have evidenced a greater sympathy for the view that the clause bars preferential

governmental promotion of some religions but allows governmental promotion of all religion in general. Nonetheless, the Court remains sharply split on how to interpret both clauses.”[39]

c. Cases – Applying the Freedom of Religion

In Jacobson v. Massachusetts (1905), the Supreme Court upheld compulsory smallpox vaccinations despite individual religious beliefs.[40] The court noted that personal freedoms must, at times, be relinquished for the benefits of the larger society.[41] However, in 1988, Ginger and David Twitchell were charged with manslaughter in the death of their 2-year-old son. The Twitchells sought to treat their son’s bowel obstruction through spiritual means. In Commonwealth v. Twitchell and Commonwealth v. Twitchell, Massachusetts’ highest court overturned their conviction, ruling that the couple had not received a fair trial.[42]

Additionally, the Illinois Supreme Court held in the case of In re Estate of Brooks (1965) that a county judge’s ordered transfusion for a Jehovah’s Witness was an unconstitutional invasion of a person’s religious beliefs.[43] In similar cases, a Milwaukee judge refused to order blood transfusions for a 6-year-old boy whose mother objected.[44] Consider how in 1982, a Chicago man who was a Jehovah’s Witness who needed a leg amputation was given court-ordered blood transfusions to keep him alive so that his children would have a father.[45] Another Jehovah’s Witness, injured in a road accident, refused blood and was transferred to Chicago to receive an experimental blood substitute, but died.[46] Each of these instances emphasize the method, facts, and legal standards used to apply the Freedom of Religion clause. Without question, the court remains committed to provide as much support to one’s religious freedom as available once all rights (federal, state, and individual) are fully balanced.

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT I

Part II – Freedom of Speech

or abridging the freedom of speech

Freedom of Speech[47]

The Constitution refers to an abbreviated form of the freedom of speech. It is highly emphasized and shortened as simply “freedom of speech,” but in fact the authors of this textbook believe the abridging portion of the Constitution should be closely examined to identify what was meant by this non-absolute freedom. Free Speech may take many forms, but typically falls in one of two categories generally, verbal/pure speech and symbolic speech. In most instances again, individuals refuse to believe that Freedom of speech or free speech (really shortened and identified in a supportive manner) is absolute. The judicial branch and the legislative branch tend to work simultaneously as well as individually to interpret this freedom. However, both branches agree that freedom of speech is not and can not be absolute as its protection is meant to be balanced with state, federal, and individual perspectives. Furthermore, although the amendment’s verbiage states “or abridging freedom of speech” (abridge meaning “to reduce or diminish”) it has long been held for more than two centuries that the freedom of speech is restricted by its impact on other freedoms.[48]

a. Verbal Speech

In this context, verbal speech is “[t]he expression or communication of thoughts or opinions in spoken words; something spoken or uttered.”[49] In short, the verbal speech indicates that the government can not administer penalties of imprisonment, fines, or other punishment on persons or organizations contingent on what they say, unless extraordinary circumstances occur. Yelling fire in a crowded movie theatre, making anti-war statements in a protest, as well as speaking against racial and social justice in a Black Lives Matter protest are constitutionally protected verbal speech as held in Cox v. Louisiana (1965).[50] The court held that anti-abortion protesters are constitutionally protected even if their speech incites opponents.[51]

b. Symbolic Speech

Also, symbolic speech is “[c]onduct that expresses opinions or thoughts, such as a hunger strike or the wearing of a black armband. • Symbolic speech does not enjoy the same constitutional protection that pure speech does.”[52] In short, the symbolic speech indicates that the government can not administer penalties of imprisonment, fines, or other punishment on persons or organizations contingent on their behavior meant to convey their thoughts with actions, things, experiences or anything or than words, unless extraordinary circumstances occur. The Supreme Court of the United States has noted symbolic speech includes students who wear armbands, burn an American flag, burn crosses, and view child pornography according to New York v. Ferber (1982).[53] The court held that child pornography which depicts sexual conduct is unconstitutional as it may provide an incentive to create an environment of sexual abuse for children.[54]

c. Political Expression

In the highly controversial decision of Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010), a bare majority of the Roberts’ Court overturned two prior rulings. The Roberts’ Court held that the First Amendment protects corporations’ and unions’ direct expenditures for candidates for federal office.[55] In a 5-4 majority opinion, Justice Anthony Kennedy found that corporations and unions are entitled to First Amendment protection for political expression and the restrictions on their ability to endorse or oppose individual candidates are unconstitutional.[56] In fact, the activities such as voting and actively opposing governmental actions adds validity to the American government.[57] “It ensures accountability of the government and prevents them from stifling critical views. However, this right is subject to restrictions, and cannot extend to violence or any other activity that disrupts public order.”[58] Previously, legal donations had to come from Political Action Committees (PACs), not directly from corporations and unions. In the first five years following Citizens United (2010), campaign spending exploded. Over time, some of the donations came from millions of individuals, the new “Super PACs, ” raising unlimited amounts from the wealthy, spent $3 billion on federal races.[59] Incumbent candidates learned to fear a well-funded primary challenge more than general election swing voters. In 2010, billionaires spent around $31 million in federal races. By 2020 it was $1.2 billion.[60]

d. Cases – Applying the Freedom of Speech

Similarly, additional cases apply the Freedom of Speech clause. In Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969), the Supreme Court held that the First and Fourteenth Amendments protected speech advocating violence at a Ku Klux Klan rally because the speech did not call for imminent lawless action.[61] The court relied upon a two-prong test which states that

(1) speech may be unconstitutional if it is “directed at inciting or producing imminent lawless action”[62] and

(2) it is “likely to incite or produce such action.”[63]

More recently, in Counterman v. Colorado (2023), the Supreme Court held that for the government to establish that a Defendant’s statement is a “true threat” unprotected by the First Amendment, the State must prove that the Defendant had some subjective understanding of the statement’s threatening nature, based on a showing no more demanding than recklessness.[64] Over a period of several years, the Defendant allegedly sent threatening messages to the other party through Facebook.[65] The Supreme Court, in a 7-2 majority opinion written by Justice Kagan, overturned the Defendant’s conviction for harassment, after finding that the Defendant was unaware that his statements would be perceived as threatening.[66]

Whereas in Miller v. California (1973), the court looked to rules for obscenity. The court outlined the rules for obscenity, while providing state and local governments flexibility in determining the perimeters of obscenity.[67] The modified three-prong test adopted from Roth v. United States (1957) and Memoirs v. Massachusetts (1966), included:

(a) “whether ‘the average person, applying contemporary community standards’ believes the work appeals to the prurient interest,

(b) whether the work depicts or describes specific sexual conduct defined by the applicable law; and

(c) whether the work lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.”[68] Therefore, the Supreme Court of the United States provided the additional context for determining the constitutionality of obscenity as it remained ambiguous prior to the Miller decision.

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT I

Part III – Freedom of the Press

or of the press

Freedom of the Press – Democracy without Independent Press is Lethal[69]

It is important to note that per Black’s Law, press includes “the news media; print and broadcast news organizations collectively.”[70] The definition of the Freedom of the Press recognizes the enormous depths and breadths of this clause which were considered by the Framers. Currently, this expansive definition would include television, internet, digital content, radio, and as well as streaming are all subject to the “press.”

a. Verbal

This would include all outlets of verbal or spoken word press such as television, radio, and streaming platforms. In short, the verbal press indicates that the government may not attribute penalties of imprisonment, fines, or other punishment on persons or organizations contingent on verbal press, unless extraordinary circumstances occur.

b. Printed

This would include all outlets of printed word press such as magazines, books, and newspapers. In short, the printed press indicates that the government may not attribute penalties of imprisonment, fines, or other punishment on persons or organizations contingent on verbal press, unless extraordinary circumstances occur.

c. Cases – Applying the Freedom of Press

In Near v. Minnesota (1931), the court established the definition of the freedom of press.[71] The court noted that government officials can’t censor or prohibit a publication in advance with exception; however, this activity might be the cause for additional proceedings.[72] Near v. Minnesota (1931) provided the beginning framework for the definition of press, but future cases would address additional aspects of the freedom of press. In New York Times Co. v. United States (1971), the court reviewed whether President Richard Nixon’s efforts to prevent the publication of classified information known as the Pentagon Papers violated the First Amendment.[73] In this instance, the court held that the government did not present a compelling interest that would overcome “the heavy presumption against” prior restraint.[74] Prior restraint is defined as “[a] governmental restriction on speech or publication before its actual expression; esp., any government-sponsored measure to prevent a communication from reaching the public, as by requiring a license to speak, prohibiting the use of the mails, or obtaining an injunction.”[75] Although the court indicated Nixon’s efforts violated the First Amendment, the court was definitive in noting that this rule of prior restraint is not without exception. Black’s Law Dictionary identifies important moments when prior restraint exceptions occur. Therefore, prior restraints violate the First Amendment unless special circumstances arise such as obscene speech, defamatory speech, or the speech amounts to the legal standard of clear and present danger to society.[76]

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT I

Part IV – Right of the People Peaceably to Assemble

or the right of the people peaceably to assemble,

Below the photograph is a picture of “[a] construction worker [who] helped guide one of the 10 limestone slabs of the Bill of Rights as it was installed near the Arizona State Capitol in December 2012.”[77]

The fourth part of the first amendment is quite different from all other parts. As identified by the National Constitution Center, the right to peaceably assemble requires more than one individual to complete.

Note: The last two parts of Amendment I are typically referred to as political rights. These rights are combined in analysis as the ‘freedom of expression.’

Accordingly, this particular right may give the reader pause to identify it as an individual right as it can not be effectuated without additional people. Furthermore, analysis surrounding this part of Amendment I really focuses on preparation made prior to effectuating this particular right. Finally, the right to peaceably assemble usually manifests as non-verbal or symbolic speech such as picketing, marching, and protesting. The Supreme Court has extended this right from federal jurisdictions to state jurisdictions in De Jonge v. Oregon (1937).[78]

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

The Democratic-Republican Societies, suffragists, abolitionists, religious organizations, labor activists, and civil rights groups have all invoked the right to assemble in protest against prevailing norms. When the Supreme Court extended the right of assembly beyond the federal government to the states in its unanimous 1937 decision De Jonge v. Oregon, it recognized that “the right of peaceable assembly is a right cognate to those of free speech and free press and is equally fundamental.”[79]

Additionally, this part of the First Amendment is erroneously referred to in so many outlets as a freedom. The 14th Amendment and many of the state constitutions extends this right to the states as well.[80] However, similar to freedoms being inherent and not absolute, rights are regulated by governmental entities and are restricted as well. The government must institute reasonable, content neutral restrictions. These restrictions speak to time, place and manner of the activity which is being sought.[81]

Therefore, one must apply the three-prong test below to begin the content-neutral restrictions test.

- The regulation must be content neutral.

- It must be narrowly tailored to serve a significant governmental interest.

- It must leave open ample alternative channels for communicating the speaker’s message.[82]

a. What kinds of restrictions would pass as content neutral?

Following the content neutral discussion, we define the “freedom of assembly.” It does not exist in Black’s Law Dictionary. Equally refreshing and disturbing is that its entry points to the right of assembly. This important fact is refreshing as the leading resource on defining legal terms recognizes that the fourth part of the First Amendment is in fact a right and not a freedom as shown in most cartoons and erroneously quoted by elected officials when discussing the First Amendment.

Unfortunately, it remains equally disturbing because it fails to include an important part of the fourth portion which reads “peaceably to assemble.” The authors recognize that most scholars would skip over this verbiage, but we submit that it is this phrase that should cast light on this amendment. It appears that most readers look to define this right, by what it does not allow – unlawful assembly. According to Black’s, unlawful assembly is defined as “a meeting of three or more persons who intend either to commit a violent crime or to carry out some act, lawful or unlawful, that will constitute a breach of the peace.”[83] Assemble defined is the concept “(of people) gather[ing] together in one place for a common purpose.”[84] Whereas, assembly is “[a] group of persons who are united and who meet for some common purpose.”[85]

In addition, defining a term by using the term in the definition is never appropriate; however, this definition of assemble has problems for many other reasons. For example, the definition speaks of two ways unlawful assembly can occur. Obviously, a crime or unlawful act makes sense – what doesn’t make sense is the indication that a lawful act which “constitutes a breach of the peace.” This may be interpreted in many ways, but essentially this particular ambiguity was struck down by the Supreme Court of the United States in City of Chicago v. Morales (1999).[86] The court invalidated an ordinance meant to address gang activity as vague when Justice John Paul Stevens reminded parties that regular individuals who are standing around for a lawful purpose would have no way of knowing if this activity would violate the statute.[87] Thus, the unlawful assembly definition would be invalidated as a reasonable interpretation per Justice Stevens.

Furthermore, many people misquote the Constitution inserting peacefully, rather than peaceably. The term peacefully as it relates to right of assembly is a Constitutional right – guaranteed by the First Amendment – of the people to gather peacefully for public expression of religion, politics, or grievances. As you review this portion of the amendment, concentrate on identifying the differences between peacefully and peaceably. Peaceably is defined as being in a way that does not involve or cause argument or violence. Whereas, peacefully is defined as being in a way that does not involve a war, violence or argument. How does peaceably differ from peacefully? Which would you prefer in analyzing your right to peaceably assemble? How does the terms affect the context of the remainder of the terms in this portion of the amendment?

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT I

Part V – Right to Petition the Government for A Redress of Grievances

and to petition the government for a redress of grievances

Whatever happened to the right to petition?[88]

The last part identifies the fifth part of the First Amendment which is a response to issues identified prior to the establishment of America. In this instance, many of our forefathers recalled how King George III ignored colonists’ petitions for redress of grievances. According to the National Constitution Center, an issue which arose in 1844 from then House of Representatives member John Quincy Adams dared to bring petitions from slaves who requested their freedom.[89] In response, House leadership imposed a limit on petitions creating, in essence, a voluntary ignorance of petitions. This part of the First Amendment is erroneously referred to in so many outlets as a freedom. The verbiage of the First Amendment is intricately connected to the fourth portion of the First Amendment. You will note that the fourth portion explicitly identifies that section as a right, while the comma as well as the word “and” (, and) reminds the reader that the right for this section is implicit.

Cases – Applying Right to Petition

“The Clause’s reference to a singular “right” has led some courts and scholars to assume that it protects only the right to assemble in order to petition the government. But the comma after the word “assemble” is residual from earlier drafts that made clearer the Founders’ intention to protect two separate rights.”[90] How is this implicit right protected? In NAACP v. Button (1963), states were precluded from barring the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) from gathering people to serve as litigants to federal petitions as a challenge and protest to segregation.[91] The court held that the NAACP activities were protected under the United States First Amendment, Right to Petition.[92]

Comparatively, in Buckley v. American Constitutional Law Foundation (1999), the court held Colorado’s requirements involving petition circulators as unconstitutional.[93] The court struck down Colorado’s initiative-petition law due to its mandated requirements for people circulating petitions must be a registered voter, wear identification brandishing one’s name and address, as well as file monthly disclosures.[94]

According to Black’s Law, redress and grievance are defined respectively as “relief or remedy” and “[a]n injury, injustice, or wrong that potentially gives ground for a complaint.”[95] This portion of the First Amendment provides options for those who feel harmed by the government to request relief for those harms. Again the redress is limited based upon the activity of the grievance. As a result of this right, many of the people in the United States have used various forms of a petition to harms caused by the government. A petition is defined as “[t]o make a formal request, esp. in writing; to entreat, solicit, or supplicate.”[96] The petition sets forth a standard and format identified by the governing entity for the particular activity. Petitioning the government for a relief of harms is well established and dates back to the 18th Century.[97] Individuals are encouraged to follow this practice as a tradition and effective method of disposing of grievances.

According to Law Professor Gregory Mark explained the complicated background of the petition as “a social, political, and intellectual story … of a constitutional and legal institution. Understood properly, it tells us about popular participation in politics, especially by disenfranchised groups.”[98] These disenfranchised groups include, but are not limited too, women, African-Americans, Native Americans, and convicted felons to name a few.[99] Typically petitions are divided into four categories: political petitions, legal petitions, public purpose petitions, and internet petitions. The political petition is defined as a document which “have a specific form, address a specific rule set by the state or federal government. Typical examples include nominating petitions filed by political candidates to get on a ballot, petitions to recall elected officials, and petitions for ballot initiatives.”[100] Additionally, legal petitions are defined as a document used to “ask a court to issue a specific order in a pending case or lawsuit, typically filed by attorneys according to court rules using specific forms.”[101]

Whereas a public purpose petition is defined as a tool that “ask officials to take or not take a specific action. They might be addressed to policymakers, government bodies, or administrative agencies.”[102] The petitions have minimal or a literally absent requirements.[103] Finally, the internet petitions are defined as documents which “are conducted entirely online. They are not always specific as to what actions to take and do not follow established civic or political processes. They are effective at raising public awareness about an issue.”[104] Each of these legal documents serve different purposes. Finally, whereas all petitions can bring about change, the public purpose and internet petitions serve as informational and a grassroots approach to change.

Critical Reflections:

- Explain how the First Amendment affects whether or not an individual must accept a vaccine to ward off a public nuisance disease (Covid-19).

- How does peaceably compare to peacefully? How does one determine if individuals are peaceably assembling? Should we refer to this section as unlawful assembly? Why or Why not?

- Evaluate the concept of natural rights vs. positive rights given the Framers’ intentions in the First Amendment.

- Describe examples of freedoms or rights within the First Amendment. What conditions may exist to make these activities become Constitutional violations?

- Volokh, E. (2020, October 15). First Amendment. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/First-Amendment ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Volokh, E. (n.d.). Adoption and the common law background. Legal Information Institute. Retrieved December 12, 2020, from https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution-conan/amendment-1/adoption-and-the-common-law-background#:%7E:text=Madison’s%20version%20of%20the%20speech,bulwarks%20of%20liberty%2C%20shall%20be ↵

- CONSTITUTIONAL FREEDOM, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- RIGHT, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHT, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Campbell, J. (2018, July 9). What did the First Amendment originally mean? Richard Law. https://lawmagazine.richmond.edu/features/article/-/15500/what-did-the-first-amendment-originally-mean.html ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Jefferson, T. (1984). Thomas Jefferson: Writings (LOA #17): Autobiography / Notes on the State of Virginia / Public and Private Papers / Addresses / Letters. Library of America, p.593. ↵

- RELIGION, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Library of Congress. (n.d.). Freedom of speech: Historical background | constitution annotated | Congress.gov | library of congress. Constitution Annotated. Retrieved May 3, 2021, from https://constitution.congress.gov/browse/essay/amdt1-1-1/ALDE_00000390/#ALDF_00005678 ↵

- ESTABLISHMENT CLAUSE, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Everson v. Board of Education, 330 U.S. 1 (1947). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. at 15-16. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- FREE EXERCISE CLAUSE, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, 597 U. S. _______(2022). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Lemon v. Kurtzman, 403 U.S. 602 (1971). ↵

- Vile, J. (n.d.). Snake handling. The First Amendment Encyclopedia. Retrieved May 1, 2021, from https://www.mtsu.edu/first-amendment/article/928/snake-handling ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Harden v. State, 188 Tenn. 17 (Tenn. Supreme Court, 1948). ↵

- Gruberg, M. (n.d.). Blood Transfusions and Medical Care against Religious Beliefs. The First Amendment Encyclopedia. Retrieved May 1, 2021, from https://www.mtsu.edu/first-amendment/article/908/blood-transfusions-and-medical-care-against-religious-beliefs ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Wisconsin v. Yoder, 406 U.S. 205, 215 (1972). ↵

- Carson v. Makin, 596 U.S. ______ (2022). ↵

- 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis et al., 600 U.S. ________(2023). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- The 303 Creative decision and expressive conduct. (n.d.). National Constitution Center – constitutioncenter.org. https://constitutioncenter.org/blog/the-303-creative-decision-and-expressive-conduct ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis et al., 600 U.S. ________, at 7 (2023). ↵

- 494 US 872 (1990). ↵

- Library of Congress (n.d.). ↵

- Commonwealth v. David R. Twitchell and Commonwealth v. Ginger Twitchell, 617 N.E.2d 609 (1993). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- In Re Estate of Brooks, 205 N.E.2d 435 (1965). ↵

- Gruberg, M. (n.d.) ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- wiredforlego. Free Speech * Conditions Apply. CC BY-NC 2.0. Flickr. ↵

- ABRIDGE, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- SPEECH, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536 (1965). ↵

- Id. ↵

- SPEECH, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- New York v. Ferber, 458 U.S. 747 (1982). ↵

- Id. ↵

- O’Brien, D. M., & Silverstein, G. (2020). Constitutional Law and Politics: Struggles for power and governmental accountability. ↵

- Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, 558 U.S. 310 (2010). ↵

- Nyaaya. (2022, August 23). What is the Freedom of Political Expression - Nyaaya. https://nyaaya.org/legal-explainer/what-is-the-freedom-of-political-expression/. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Waldman, M. (2023). The supermajority: How the Supreme Court Divided America. Simon and Schuster. p. 84-85. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.A. 444 (1969). ↵

- Id. at 447. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Counterman v. Colorado, 600 U.S. _______(2023). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Miller v. California, 413 U.S. 15 (1973). ↵

- Id.; Roth v. United States, 354 U.S. 476 (1957); Memoirs v. Massachusetts, 383 U.S. 413 (1966). ↵

- Manmeet. (2023). Democracy without Independent Press is Lethal. The Legal Observer. https://thelegalobserver.com/democracy-without-independent-press-is-lethal/ ↵

- PRESS, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S. 697 (1931). ↵

- Id. ↵

- New York Times Co. v. United States, 403 U.S. 713 (1971). ↵

- Id. ↵

- PRIOR RESTRAINT, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Gonchar, M. (2016, December 15). Text to Text | The Bill of Rights and ‘The Bill of Rights We Deserve.’ The Learning Network. https://archive.nytimes.com/learning.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/09/25/text-to-text-the-bill-of-rights-and-the-bill-of-rights-we-deserve/ ↵

- De Jonge v. Oregon, 299 U.S. 353 (1937). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Hague v. Committee for Industrial Organization, 307 U.S. 496 (1939). ↵

- Ward v. Rock Against Racism, 491 U.S. 781 (1989). ↵

- Id. ↵

- UNLAWFUL ASSEMBLY, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Oxford University Press. (2021). Assemble. In Oxford English Dictionary. https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/11787?rskey=1ZFpny&result=2&isAdvanced=false#eid ↵

- Oxford University Press. (2021). Assembly. In Oxford English Dictionary. https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/11795?redirectedFrom=assembly#eid ↵

- City of Chicago v. Morales, 527 U.S. 41 (1999). ↵

- Id. ↵

- elPadawan. First Amendment to the US Constitution. CC BY-SA 2.0. Flickr. ↵

- Inazu, J., & Neuborne, B. (n.d.). Interpretation: Right to assemble and petition | The National Constitution center. Interactive Constitution. Retrieved May 19, 2021, from https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/interpretation/amendment-i/interps/267 ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Buckley v. American Constitutional Law Foundation, Inc., 525 U.S. 182 (1999). ↵

- Id. ↵

- GRIEVANCE, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024); REDRESS, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- PETITION, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Right to petition. (n.d.). https://www.americanbar.org/groups/public_education/publications/insights-on-law-and-society/volume-20/issue-1/learning-gateways--right-to-petition/. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵