Chapter 10 – Amendments XIII, XIV, XV, and XXIV: Becoming Human, Becoming a Citizen, & Becoming a Voter

Amendment XIII, Amendment XIV, Amendment XV & Amendment XXIV

Richard J. Forst and Tauya R. Forst

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

10.1 Define the unfamiliar terms of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, Fifteenth, and Twenty-Fourth Amendments.

10.2 Explain the parts of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, Fifteenth, and Twenty-Fourth Amendments.

10.3 Define Due Process, Procedural Due Process, and Substantive Due Process.

10.4 Explain the difference between Procedural Due Process and Substantive Due Process.

10.5 Define Equal Protection.

10.6 Explain the differences between Slavery and Involuntary Servitude.

10.7 Explain the evolution of the Supreme Court position on education from Plessy v. Ferguson to Brown v. Board of Education.

10.8 Define “Poll Tax” and explain what the government is allowed to require for an individual to vote.

10.9 Explain the evolution of the Supreme Court position on the Voting Rights Act, from its passage in 1965 to the present.

KEY TERMS

| Affirmative Action | Privileges or Immunities Clause |

| Brown v. Board of Education | Procedural Due Process |

| Disenfranchisement | Separate but Equal |

| Equal Protection | Shelby County v. Holder |

| Involuntary Servitude | Slavery |

| Manumission | Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard |

| Native Americans | Substantive Due Process |

| Plessy v. Ferguson | Voting Rights Act of 1965 |

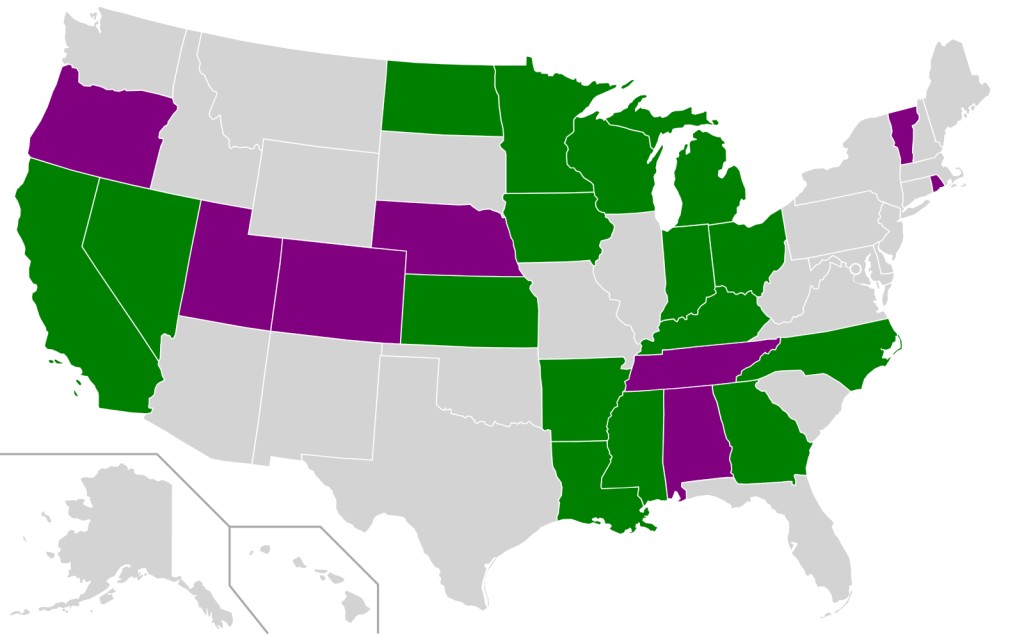

Figure 10.1 – History of Amendment XIII

| Census Year | Free Colored | Slaves | American Indians* (Native Americans) |

Whites | Asians* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 59,466 | 607,897 | N/A | 3,172,006 | N/A |

| 1800 | 108,395 | 803,041 | N/A | 4,302,828 | N/A |

| 1810 | 186,446 | 1,101,364 | N/A | 5,862,073 | N/A |

| 1820 | 233,521 | 1,538,038 | N/A | 7,866,797 | N/A |

| 1830 | 319,590 | 2,009,043 | N/A | 10,532,060 | N/A |

| 1840 | 386,303 | 2,487,455 | N/A | 14,189,705 | N/A |

| 1850 | 434,440 | 3,204,313 | N/A | 19,553,068 | N/A |

| 1860 | 487,970 | 3,953,760 | 339,421** | 26,922,537 | 34,933 |

*American Indian and Asian data unavailable until 1860

**Taxed Native Americans/American Indians 44,021, Not Taxed 295,400 = Total 339,421[1] [2]

Figure 10.2

YELLOW = free colored; GREEN = slaves

Prior to 1900, few Indians are included in the decennial federal census. Indians are not identified in the 1790-1840 censuses. In 1860, Indians living in the general population are identified for the first time.[3]

AMENDMENT XIII

Passed by Congress January 31, 1865. Ratified December 6, 1865. The 13th Amendment changed a portion of Article IV, Section 2.

Section 1

Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Section 2

Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

Thirteenth Amendment Documentary[4] Combining archival footage with testimony from activists and scholars, director Ava DuVernay’s examination of the U.S. prison system looks at how the country’s history of racial inequality drives the high rate of incarceration in America

INTRODUCTION TO AMENDMENT XIII

Although the Thirteenth Amendment was ratified almost 100 years after the original United States Constitution, the question remains, from which historical context can we view this ratification? Because of the concern of some states to reverse decisions of abolishing slavery, “Senators Lyman Trumbull of Illinois, Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, and John Henderson of Missouri, sponsored resolutions for a constitutional amendment to abolish slavery nationwide.”[5]

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT XIII

a. Right against slavery

Neither slavery… shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Historically, the Thirteenth Amendment was approached in terms of what its suggested legal impact was; however, the Thirteenth Amendment provided a more fundamental opportunity for those who were directly targeted as well as those who were tangentially connected. First, and perhaps most important, the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments are recognized and digested together as the Reconstructionist Amendments. Each of the amendments represented and addressed a response to the then-prevalent practice of dismissing, ignoring, and otherwise disregarding basic human rights to specific groups and classes of people.

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

It is difficult to understand its significance without first remembering the Thirteenth Amendment’s historical context.

The Thirteenth Amendment’s purpose was to address what had been lying beneath the surface, since before the United States of America was formed. To properly and respectfully address this amendment, we must begin with the make-up of the geographical area which would later be deemed the Americas. Prior to 1492, the Natives or Indigenous peoples inhabited this land. This land is their land, and all who seek to possess and build must make acknowledgement of this fact. Christopher Columbus, who is noted to have founded this inhabited land, immediately seized six natives and used them as his servants. It is this concept which continues to plague our current society.[6] Eventually, other explorers came to the Americas and began to possess the land, while dispossessing its Native inhabitants.[7] The Native American term isn’t settled. In fact, “[t]he United States’ Constitution, more than 300 treaties, and over two centuries of Federal law recognize Indian tribes as domestic dependent nations with degrees of sovereignty existing within the confines of the United States.”[8]

This means that many may attribute different names to Native Americans including American Indian, Indigenous Peoples, however, tribal nation affiliation is a preferred terminology.[9] It is important to note that the United States Census does maintain a formal definition for Native Americans. “The U.S. Census defines Native American, American Indian or Alaska Native as “A person having origins in any of the original peoples of North and South America (including Central America) and who maintains tribal affiliation or community attachment.”[10] This is well documented and from this settlers’ mentality of possession and colonization throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, a continuous battle of disrespect and rewriting of history begins between the settlers and the Natives spanning the gamut of “cooperation to indignation to revolt.”[11] The Natives clearly recognized that dispossession and interference with their practices, beliefs, and governance was displaced and perverted to fit within this newly colonized way of living.

Similarly, Africans were noted for joining the Spanish and Portuguese in their exploration of America. One of the most notable African settlers was Esteban from the 1530s. Africans continued their appearances until 1619 when the impact of Africans took a very dire turn.[12] The concentrated emphasis of Africans within the United States began not as most believe. Historians dispute various aspects of the Africans existence; however, all agree that the early Africans were enslaved in Virginia. Africans were first bought to the English colony as servants, but their use extended beyond normal parameters of servitude. At this time the colonists began to build their wealth and status and believed that the key to maintenance of this new lifestyle was to convert the statuses of runaway servants into involuntary servants for life.[13] Furthermore, this conversion was typically given to those who were of non-African descent. Replacing the servitude and making the service permanent, Africans became slaves for life. This is an important distinction. Compared to the inhumane condition of slavery, involuntary servitude is considered the slaves’ dream. The seriousness of this institution is only fully appreciated after one reads how slavery made humans into property. Slavery is defined as “[a] situation in which one person has absolute power over the life, fortune, and liberty of another.”[14] Of note is the fact that the complete and utter totality of a person’s existence is removed in slavery. In fact, slaves were deemed less than human, chattel, or most importantly, the property of the colonists. Therefore, slaves were not allowed to make any decisions, plans, or have any thoughts for themselves or their families.

Accordingly, the legal conditioning and denial of activities of daily living which faced African slaves provides context for the absolute horror of inhumanity which was the slaves’ “normal” existence. The following is a list of treatments offered as a reminder and indication of the vastness, depth, and breath of slavery.

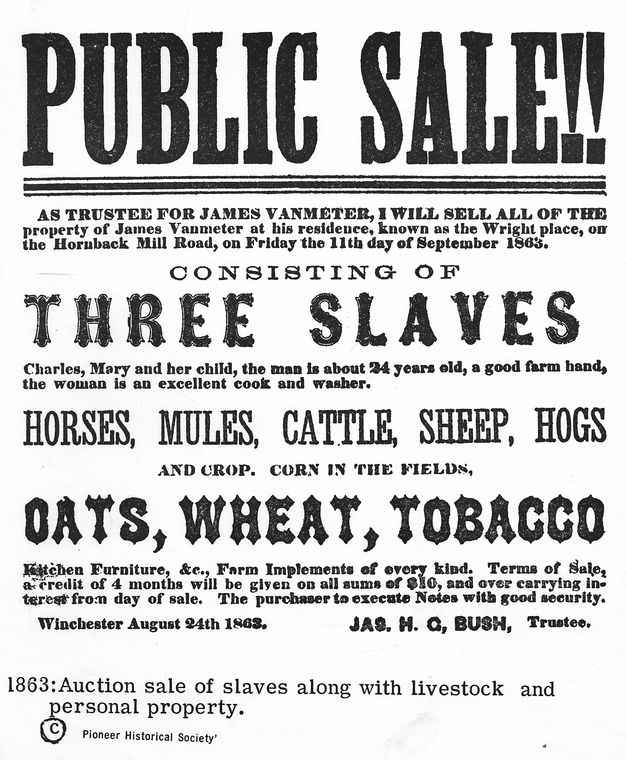

Public Sale of Slaves, Livestock, and other Personal Property[15]

As such, each enumerated fact or condition provides context for the hatred of America’s dark history and foundations towards African slaves:

(1) slaves are property, and can be sold, traded, given away, bequeathed, inherited, or exchanged for other things of value;

(2) the status of a slave is inheritable, usually through the mother;

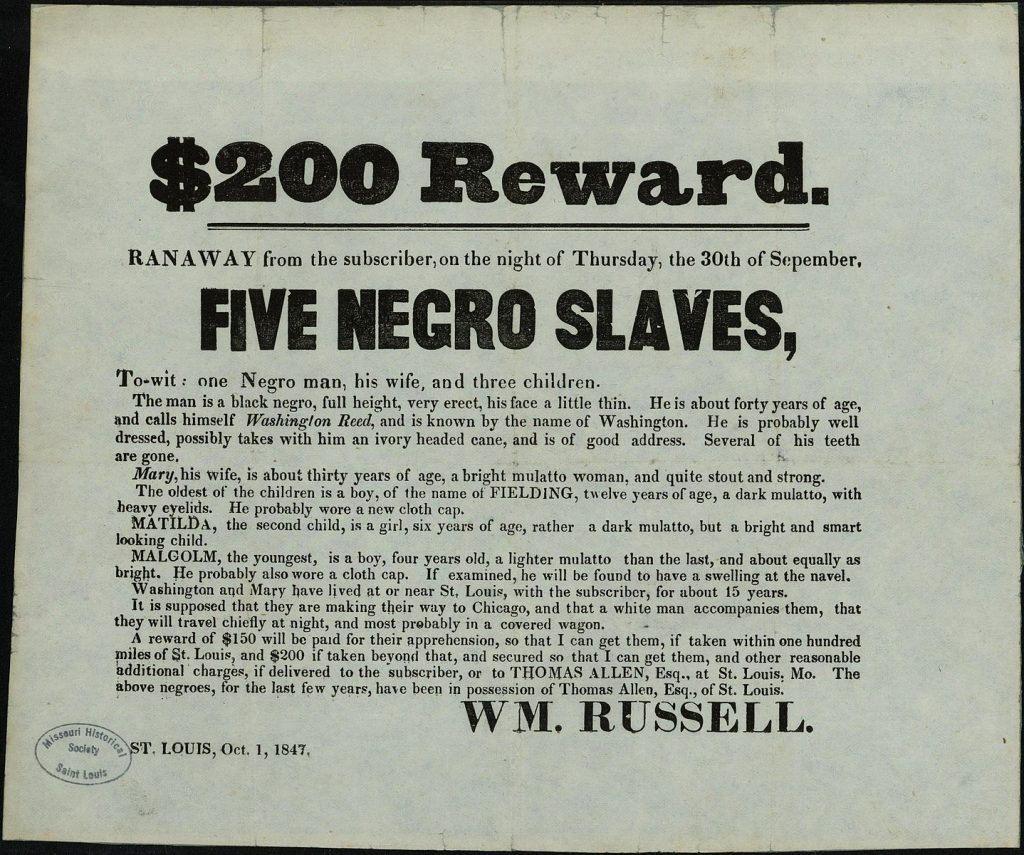

(3) formal legal structures or informal agreements regulate the capture and return of fugitive slaves;

“After a person escaped enslavement, many relied on northern whites to lead them safely to the northern free states and to Canada. It was very dangerous to be a formerly-enslaved person. There were rewards for their capture, and advertisements like the reward poster here described people in detail. This reward poster from 1847 described five formerly-enslaved people: a man, his wife and his three children. Whenever a northerner led a group of enslaved people to freedom, they placed themselves in great danger, too.”[16]

(4) slaves have limited (or no) legal rights or protections;[17]

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) was a landmark Supreme Court of the United States’ decision that upheld the constitutionality of racial segregation under the “separate but equal” doctrine.[18] Mr. Plessy had refused to sit in a railroad car set aside for black people, and was arrested for violating Louisiana’s “Jim Crow” law. Only one Justice dissented from the majority decision, John Marshall Harlan, a former slaveholder, who argued that segregation ran counter to the constitutional principle of equality under the law. It would not be until 1954, in Brown v. Board of Education, that the majority of the Court would essentially concur with Harlan’s dissent.[19]

(5) slaves (regardless of age) may be punished by slave owners (or their agents) with minimal or no legal limitations;

(6) masters may treat, or mistreat, slaves as they wish, although some societies required that masters treat slaves ‘humanely’ and some societies banned murder and extreme or barbaric forms of punishment and torture;

(7) masters have unlimited rights to sexual activity with their slaves;

(8) slaves have very limited or no appeal to formal legal institutions;

(9) slaves are not allowed to give testimony against their masters or (usually) other free people, and in general their testimony is not given the same weight as a free person’s;

(10) the mobility of slaves is limited by owners and often by the State;

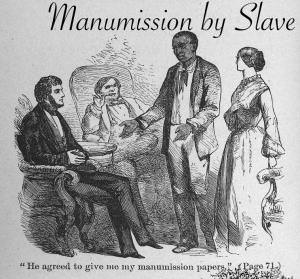

(11) owners are able to make slaves into free persons through a formal legal process (manumission), but often these freed persons are not given full legal rights (even when you are free, you are not free indeed or equal); (Manumission is defined in Black’s as “the granting of freedom to a slave.”[20] But the manumission was usually unsanctioned by law and therefore the extent of the freedom granted was whatever the slaveholder allowed.[21])

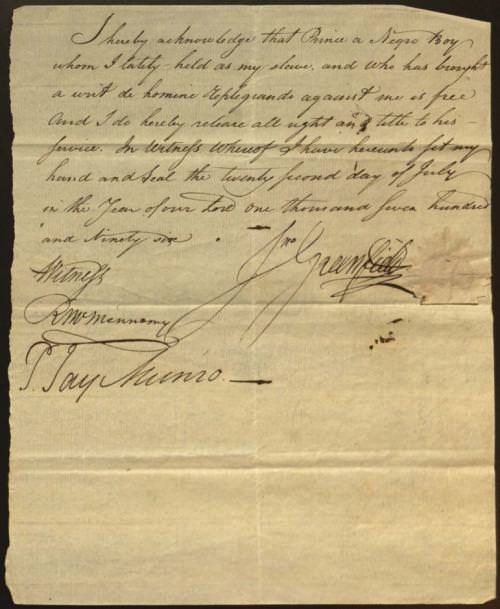

“Prince, a man enslaved in New York, had the courage to bring a writ of Homine Replegiando, which essentially states that a person is being unlawfully held. His petition was successful, and Prince was manumitted in due course.”[22]

“Transcription: I hereby acknowledge that Prince a Negro Boy whom I lately held as my slave, and who has brought a writ of homine replegiando against me is free and I do hereby release all right and title to his service. In witness whereof I have hereunto set my hand and Seal the twenty second day of July in the Year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and Ninety six.

“Transcription: I hereby acknowledge that Prince a Negro Boy whom I lately held as my slave, and who has brought a writ of homine replegiando against me is free and I do hereby release all right and title to his service. In witness whereof I have hereunto set my hand and Seal the twenty second day of July in the Year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and Ninety six.

Tho. Greenfield

Witness

R. W. Mennomy

T. Jay Munro”[23]

(12) slave ownership is supported by laws, regulations, courts, and legislatures, including provisions for special courts and punishments for slaves, provisions for the capture and return of fugitive slaves, and provisions and rules for regulating the sale of slaves.”[24]

The authors explicitly share the conditions of slavery in an effort to distinguish between slavery and involuntary servitude as it relates to the Thirteenth Amendment. The first clause of the United States Constitution points to both of these incredibly barbaric concepts which indicates the founders’ understanding and intention to address two entirely different systems. At any rate, the founders believed that both of these institutions were unconstitutional, but its verbiage leaves a loophole for constitutionality.

This concept was deeply embedded in our foundational fabric as a nation and continues to haunt us as we make strides to address some of its institutional and systemic effects which led to systematic racism.

“Slavery was a big problem for the Constitution makers. Those who profited by it insisted on protecting it; those who loathed it dreaded even more the prospect that to insist on abolition would mean that the Constitution would die aborning. So the Framers reached a compromise, of sorts. The words ‘slave’ and ‘slavery’ would never be mentioned, but the Constitution would safeguard the ‘peculiar institution’ from the abolitionists.”[25]

In 1861-1865, the leaders of the United States of America began to determine and define what kind of nation the United States of America would be.

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

In fact, it is the Civil War fought by northerners and southerners, brothers and other relatives which proved to be influential in the country’s two-part challenge: “whether the United States was to be a dissolvable confederation of sovereign states or an indivisible nation with a sovereign national government; and whether this nation, born of a declaration that all men were created with an equal right to liberty, would continue to exist as the largest slaveholding country in the world.”[26]

The so-called Northern victory was anything but a victory, considering the loss of American life (often complete with blood relatives opposing one another) amounted to 625,000.[27] Additionally, this number represented the total loss of American lives from all previous wars combined. This is aside from the enormous financial cost to both sides of the conflict: $6.19 billion for the North, $2.1 billion for the South, over $8 billion combined, in 1865 dollars.[28] This is particularly problematic as the post-War nation attempts to heal, connect and present a united front.

The proponents of the Civil War aimed to demolish inequities in the structure of government as well as in the human dignity of its inhabitants. The aftermath of the Reconstruction was a moment of liberty for the former slaves which lasted until 1876. In that presidential election year, the Northern Republicans exchanged the Reconstruction guarantee of freedom to the slaves for an agreement from Southern Democrats to elevate the Republican candidate, Rutherford B. Hayes, to the presidency.[29] This arrangement would allow Southern States to pass “Jim Crow” laws which segregated blacks from white society, enforced with lynchings and terror raids on black homes and businesses.[30]

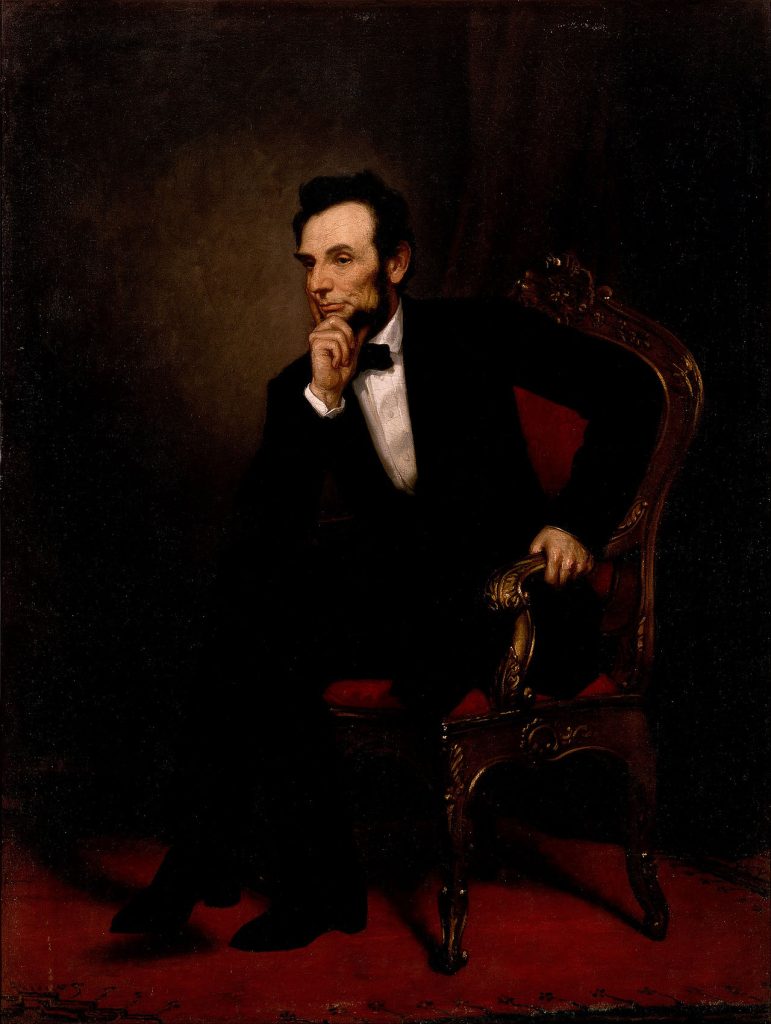

Although the country was formed as the United States of America, predating its existence America struggled with this concept of equity and even equality. Historians note an ongoing battle over property (slaves), conditions of slaves, the acceptable amount of power and its delegation between the federal government and the states remained central to every discussion during this time.[31] Proponents of slavery outlined and supported this institution based upon the surge in the economy as well as a biblical and economic authoritative approach to retaining this power. In fact, those who were proponents of slavery and those who vehemently opposed slavery were divided in part and parcel according to their stance on slavery. Unfortunately, President Abraham Lincoln’s victory in 1860 was the final precursor to states for evidence of the necessity to secede.[32] It was this point in politics that a resolution to separate become a separate entity known as the Confederate States of the United States.

The North’s approach to prosperity and sustainability was housed in its ability to diversify employment opportunities, whereas the Southern states approach began and ended with slaves, cotton, and plantation living. Thus, the equality of the promise which Lincoln supported was hotly debated.

Lincoln recognized slavery as being morally incomprehensible, but lacked the wherewithal to combat its roots and tentacles. Unfortunately like many historical figures before him, he had a two-fold response to slavery. He recognized that he could help provide freedom to the slaves, while “he had become convinced that emancipating enslaved people in the South would help the Union crush the Confederate rebellion and win the Civil War.”[34] As a result of this evolutionary thinking on September 22, 1862, President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation to take effect on January 1, 1863.[35] The Emancipation Proclamation was his first tangible and life-altering promise of freedom for slaves. Unfortunately, it would prove to be ceremonial at best. This document did not free some 4 million slaves who were most impacted by slavery, instead it functioned to free those who were slaves in Confederate states which were not Union loyalists.[36] However, what the document did operationally for Lincoln is to begin to shift his thoughts regarding slavery and its impact on the Civil War. Therefore, freedom for the slaves became one of the central points of the Civil War. Unfortunately, this left all who supported freedom for slaves to recognize that this was a heavy lift and could only be accomplished with a constitutional amendment. Recall this would take the verbiage of the amendment being approved by 2/3 of Congress and ratified by 3/4 of the states. Thus, all proponents resolved themselves to an uphill battle which ultimately culminated in the abolition of slavery in 1865, almost 100 years after the original United States Constitution was ratified in 1788. Note, operationally the United States of America would continue to reckon with this now abolished concept – struggling to legitimize and legalize slaves as humans, no longer chattel or property.

b. Right against involuntary servitude

…nor involuntary servitude,…shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Efforts by States to Eliminate the Exception Allowing Slavery or Involuntary Servitude as Punishment for a Crime[37]

As previously discussed, by some accounts early slaves and others were first used as involuntary servants. It was the greed, insecurity, and ethnocentric beliefs which led slaves to be further demeaned. Additionally, others such as Natives, non-landowning individuals were forced into involuntary servitude. Thus, the second part of the first clause of the Thirteenth Amendment – involuntary servitude – is more than likely referring to others (as opposed to African slaves) within the population of the United States in 1865. Black’s Law Dictionary defines involuntary servitude within the Thirteenth Amendment as “[t]he condition of one forced to labor – for pay or not – for another by coercion or imprisonment.”[38] This concept, although arguably difficult and illegal, does not begin to compare to the vastness of human rights which are abrogated by the institution which emerged as slavery. Whereas involuntary servitude is heartless, it allows those mandated to its terms to continue to exercise basic human rights such as marrying, conceiving, and securing and engaging in a family without interference.

However, we, the authors of this text, refuse to completely dismiss involuntary servitude, as it became a foundation for future applications of the Thirteenth Amendment. Thus, what conditions did involuntary servants find themselves sentenced to endure? The Thirteenth Amendment bans all types of working conditions where a person is forced to work without being paid something of value (in most cases). One practice was peonage. Peonage is defined as “[i]llegal and involuntary servitude in satisfaction of a debt.”[39] The practice of peonage was said to begin in New Mexico, spreading its influence across other jurisdictions after the Civil War. Essentially, those who were once slaves and other socioeconomically depressed individuals were forced to work until the debt for basic human needs and expenses were satisfied.[40] Unfortunately in many cases this repayment would never occur due to inflated charges and expenses. To this end, the involuntary servant becomes the face of those who are subjected to unfair and illegal working conditions.

The Supreme Court of the United States weighed the facts in a case and determined this unequitable financial institution was inhumane and oppressive to those who are less fortunate. In Bailey v. Alabama (1911), the Court addressed the impact of the Thirteenth Amendment and the term involuntary servitude. The Court indicated that the term “involuntary servitude “[has] a larger meaning than slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment prohibited all control by coercion of the personal service of one man for the benefit of another.”[41] In short, the court reasserted its emphasis on the concern of forcibly using a human for another human’s benefit. The U.S. v. Kozminski (1988) court further addressed and extended the concept of involuntary servitude. In U.S. v. Kozminski (1988), two mentally and physically challenged men who worked in deplorable working conditions daily. The working conditions isolated the men from the rest of the world with little or no wages.[42] Additionally, the men endured incidents of emotional, physical, and mental abuse culminating in the threat to recommit one of the men to an institution.[43] The respondent faced violations found in two criminal federal codes as well as allegations of preventing the men from duly exercising their Thirteenth Amendment right against involuntary servitude. Ultimately, the court determined that the federal statutes at issue – required a specific jury instruction for the case so the “jury must be instructed that compulsion of services by the use or threatened use of physical or legal coercion is a necessary incident of a condition of involuntary servitude.”[44] This ban on slavery and involuntary servitude was to persist throughout the United States and its jurisdictions, but there is an exception to this legal rule.

c. Right against involuntary servitude except as a punishment

except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted

Most scholars agree that the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery and involuntary servitude as it relates to all penalties after an alleged violation of a crime in which the defendant was legally convicted. These 13 words and two clauses served as a stark contrast to the current state of the Thirteenth Amendment. It reminded those who were impacted that these institutions are alive and well to those who are the least of us. It reminded the world that according to the second clause of the Thirteenth Amendment slavery and involuntary servitude are alive and well – within the prison, jail and criminal justice system.

d. Right to enforcement of Thirteenth Amendment

Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

After reading the Thirteenth Amendment, it is important to notice some distinctions within the amendment which we have not seen in any of the previous twelve amendments. First and foremost, the Thirteenth Amendment is not very long, but it has sections. This is important as the reader may ask themselves why does a small amendment require two sections. Additionally, no prior amendments have been enumerated into sections. Finally, what is the purpose of §2 of the Thirteenth Amendment as it seems repetitive in nature? This information would be true of all previous amendments, however, it was not deemed necessary as an enumerated and separate section. Finally, will other amendments have multiple sections, include this verbiage or return to the format of the first twelve amendments? It is important as you delve into the constitution that you review with scrutiny these slight, but quite significant changes to help you keep the context and history of the times close to your analysis and opinions. We return to the issue at hand – why do we have the Second § of the Thirteenth Amendment? This verbiage in the Constitutional amendment enabled proper enforcement power by appropriate legislation. Similar verbiage can be seen in the Fourteenth, Fifteenth, Nineteenth, Twenty-third, Twenty-fourth, and Twenty-sixth Amendments.

As relations between state and federal government began to deteriorate, the federal government recognized that some states would completely and holistically defer, denounce, and ignore the ratified Thirteenth Amendment.

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

This split in our country is reflective of what we see in today’s politics where opinions are polarized, as we profess our undying support and love for one entity, while being made to feel that it decimates another entity.

This same behavior was highlighted by the Federalists and Anti-Federalists. Again, we see this heightened split from the Civil War between those who supported succession – The Confederacy and those who supported a unified country – The Unionists. This same opposition has been foundational in the United States of America. This split began with the Natives and the Europeans at the “inception” of the Americas. Furthermore, we see the divide in the history of our country between those who support Women’s Suffrage as opposed to those in the country who objected to Women’s Suffrage. Additionally, we are looking to those who supported Civil Rights and those who didn’t. Perhaps, there is the fight between abolishing slavery and those who fought to keep slavery etched in this country’s fabric. If you profess Black Lives Matter, then it must be opposed by Blue Lives Matter. Thus, our country has historically and consistently finds itself in contentious and diametrically opposed spaces which requires the law and evolution of the minds of people on American soil to progress.

With this opposition in mind, Amendment XIII, §2, Amendment XIV, §5, Amendment XV, §2, Amendment XIX, §2, Amendment XXIII, §2, Amendment XXVI, §2, and Amendment XXVII, §2 all required an explicit statement that Congress is empowered to invoke suitable legislation to implement the respective amendment’s sections. Therefore, this provision is necessary for Congress to pass and/or effectuate laws to address those who persist in violating this significant amendment. With regard to the Thirteenth Amendment, “For example, the Anti-Peonage Act of 1867 prohibits peonage, and another federal law, 18 U.S.C. §1592, makes it a crime to take somebody’s passport or other official documents for the purpose of holding her as a slave.”[45] This section was necessary as it was apparent that all jurisdictions would not voluntarily follow these amendments.

As of today, this power remains invested in Congress within each of the aforementioned amendments. Legal parties have sought to further expand Congress’s authority in this area; variations of this language was added to six additional amendments. Although SCOTUS has never addressed the full purview of the Second § of the Thirteenth Amendment, it did indicate that its implication must rely upon the “badges and incidents of slavery,” described as “refers to public or widespread private action, aimed at any racial group or population that has previously been held in slavery or servitude, that mimics the law of slavery and has significant potential to lead to the de facto reenslavement or legal subjugation of the targeted group.”[46] Subsequently, the section continues to lack clarity on its implementation. “Finally, it granted Congress the power to enforce this amendment, a provision that led to the passage of other landmark legislation in the 20th century, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.”[47]

Amendment XIV

Passed by Congress June 13, 1866. Ratified July 9, 1868. The 14th Amendment changed a portion of Article I, Section 2. A portion of the 14th Amendment was changed by the 26th Amendment.

Section 1

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Section 2

Representatives shall be apportioned among the several States according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each State, excluding Indians not taxed. But when the right to vote at any election for the choice of electors for President and Vice-President of the United States, Representatives in Congress, the Executive and Judicial officers of a State, or the members of the Legislature thereof, is denied to any of the male inhabitants of such State, being twenty-one years of age, and citizens of the United States, or in any way abridged, except for participation in rebellion, or other crime, the basis of representation therein shall be reduced in the proportion which the number of such male citizens shall bear to the whole number of male citizens twenty-one years of age in such State.

Section 3

No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice-President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.

Section 4

The validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law, including debts incurred for payment of pensions and bounties for services in suppressing insurrection or rebellion, shall not be questioned. But neither the United States nor any State shall assume or pay any debt or obligation incurred in aid of insurrection or rebellion against the United States, or any claim for the loss or emancipation of any slave; but all such debts, obligations and claims shall be held illegal and void.

Section 5

The Congress shall have the power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.

INTRODUCTION TO AMENDMENT XIV

The Fourteenth Amendment addresses many aspects of citizenship and the rights of citizens. The most commonly used and frequently litigated phrase in the amendment is “equal protection of the laws,” which figures prominently in a wide variety of landmark cases, including Brown v. Board of Education (racial discrimination); Roe v. Wade (reproductive rights); Bush v. Gore (election recounts); Reed v. Reed (gender discrimination); and University of California v. Bakke (racial quotas in education). Amendment XIV followed an interesting process which began on June 16, 1866 through the House Joint Resolution.[48] On July 28, 1868, the 14th amendment was declared, in a certificate of the Secretary of State, ratified by the necessary 28 of the 37 States, and became part of the supreme law of the land.[49]

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT XIV

Section 1

a. Right to citizenship

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.

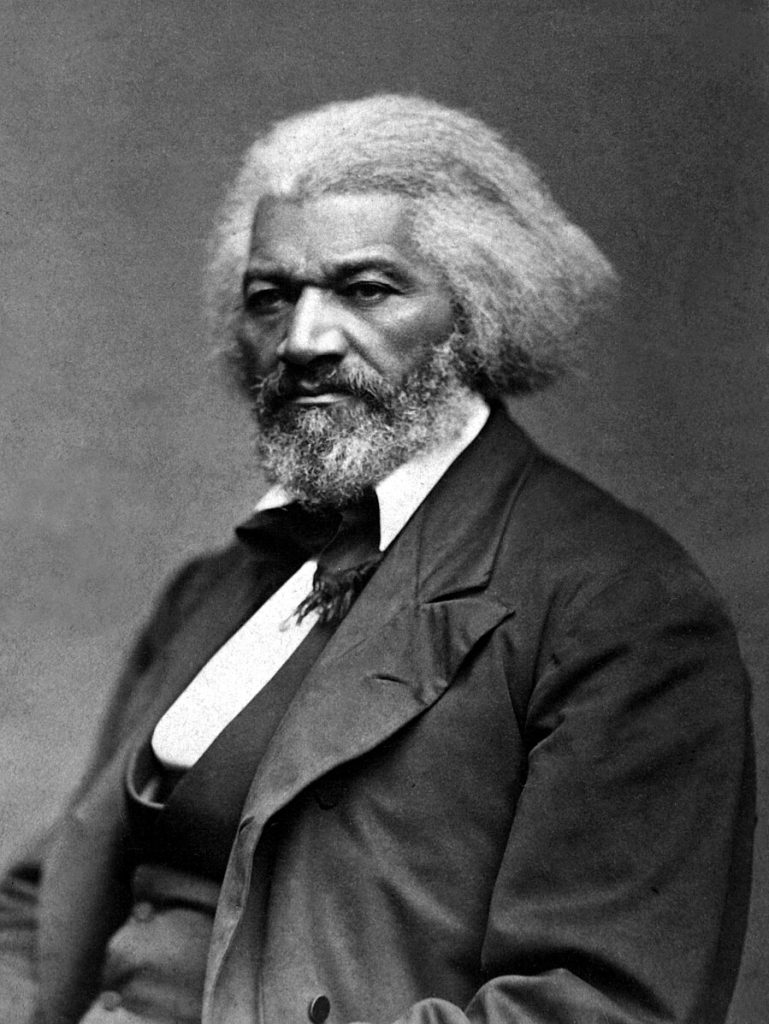

This section extends the impact of the Thirteenth Amendment further. The enslaved people who are now listed as human are now constitutionally allowed to be citizens of the United States. This part of the amendment is quite important considering the original Constitution pointed to slaves and natives as subhuman, but should be counted towards representation. Although most case law reflected a divided country, the legislative history emerged as a commonsense approach to citizenship. The Supreme Court, in the Dred Scott (1857) case, with Chief Justice Roger Taney writing for the majority, restricted citizenship by designating two types of individuals as appropriate for this status.[50] In short, the Court reminded the country that citizenship was only extended to either someone (or that person’s descendants) who was originally granted citizenship at the inception of the country or someone that was naturalized into the country.[51]. Taney held that men of African descent were “so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect…the Negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit.” The iconic Black abolitionist and statesman Frederick Douglass responded, “Judge Taney can do many things, but he cannot perform impossibilities. He cannot change the essential nature of things—making evil, good, and good, evil.”[52]

Frederick Douglass[53]

This decision solidified the divide between those who were white and natives, immigrants without naturalization, slaves, and freed slaves. As a result, this clause was applied to Chinese parents (ineligible for naturalization) and the status of their Chinese child who was born in the states. The Court leveraged this clause in United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898) when they determined that the child was entitled to the rights and privileges of United States citizenship according to §1, Cl. 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment.[54] Thus, the first portion of this amendment created a path to citizenship where one did not previously exist. Additionally, the amendment recognized and confirmed that this was recognized by some states already, but needed to be extended by the federal government if other states would consider, implement and ultimately embrace this clause.[55]

b. Right to privileges or immunities of citizens

No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States;

It’s important to note that the Fourteenth Amendment was explicit in its approach to providing a holistic cadre of rights to its newly identified citizens. The privileges and immunities clause is defined as “[t]he Constitutional provision…prohibiting a state from favoring its own citizens by discriminating against other states’ citizens who come within its borders.”[56] The implementation of this clause faced grave danger soon after it was ratified as evidenced in the Slaughter-House Cases (1873), where New Orleans’ butchers offered a violation of the national citizenship and the court explained that this was an adverse meaning of the right to privileges and immunities within this context.[57] Ultimately, the court determined that the privileges and immunities were limited to those explicitly stated within the Constitution and did not regard those rights offered by the state governments.[58] In short, the Slaughter-House Cases essentially nullified this clause with its holding.[59]

c. Right to due process

nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law;

Due Process[60]

Whereas, the previous section seemed to be reduced in its application, the current clause broadens it ability to be applied. This section is typically viewed in tandem with other mentions of due process across the Constitution such as the Fifth Amendment; although the verbiage used in both the Fifth and the Fourteenth Amendment is almost identical. There is a unique difference in the focus of the two amendments. Recall, the Fifth Amendment applies due process protections for individuals from federal government (and extended through the Incorporation Doctrine); whereas the Fourteenth Amendment applies to due process protections to individuals from local and state government.

As we identify the true essence of this clause, it is important to define due process of the law as “[t]he conduct of legal proceedings according to established rules and principles for the protection and enforcement of private rights, including notice and the right to a fair hearing before a tribunal with the power to decide the case.”[61] This amendment explicitly includes life, liberty, or property as notable dissertations of the due process of law. Further, due process of law may be distinguished based upon possible violations. On the one hand, due process may affect how the defendant proceeds through the criminal justice system. This process would include investigation to sentencing and post-conviction proceedings. Each defendant is to be treated equally at each juncture of the process. On the other hand, due process may be violated when it fails to maintain basic freedoms such as the freedom of speech or the freedom of religion.

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

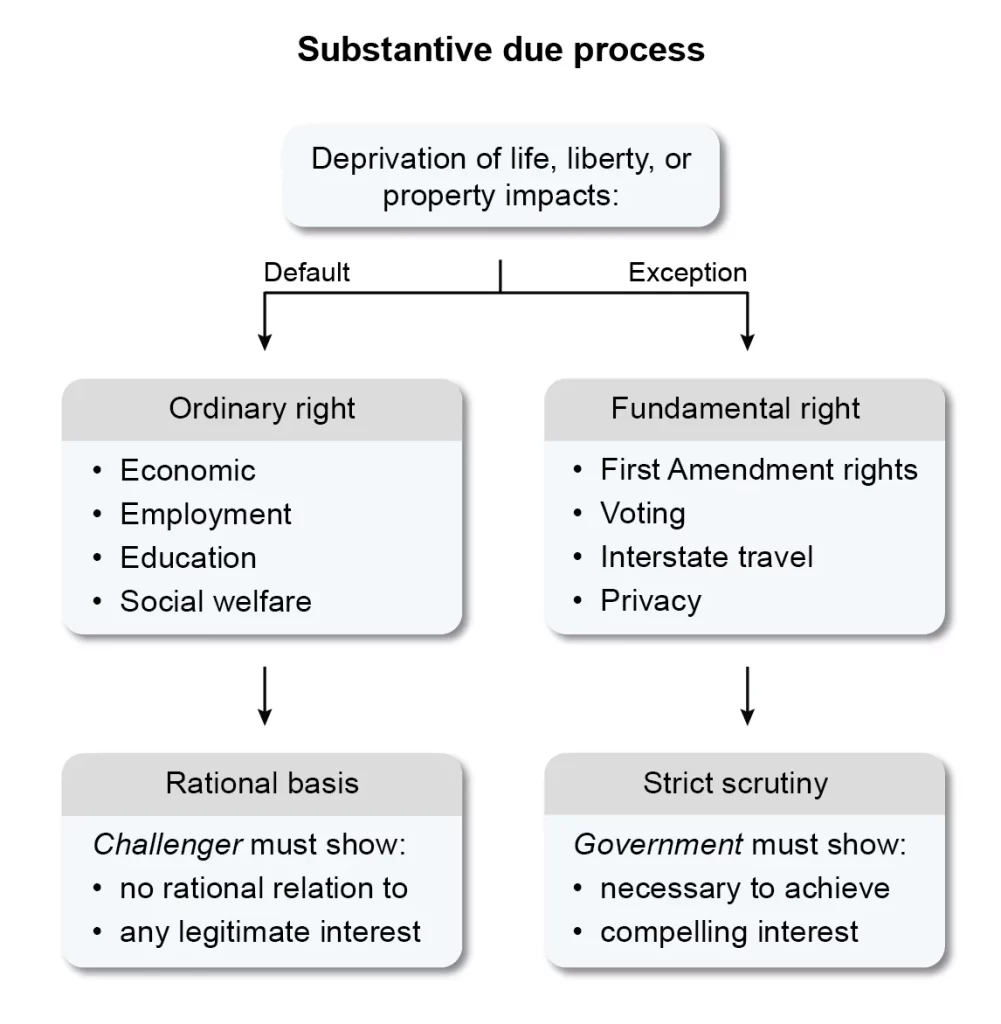

Thus, the due process concept doctrine includes two separate doctrines – procedural and substantive due process violations for the accused.

Procedural due process is defined as “[t]he minimal requirements of notice and a hearing guaranteed by the Due Process Clauses of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments, especially if the deprivation of a significant life, liberty, or property interest may occur.”[62] An example of procedural law is if two accused individuals are both engaged in the same criminal activity and one is Mirandized and arraigned for the alleged crime; while the other accused is not Mirandized and confesses to the crime. In In re Gault (1967), procedural due process protections were extended to juveniles as well when the court determined that juveniles are entitled to privilege against self-incrimination, notice of charges, and right to confront, and subpoena witnesses.[63]

Procedural Due Process[64]

Whereas, substantive due process is defined as “[t]he doctrine that the Due Process Clauses of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments require legislation to be fair and reasonable in content and to further a legitimate governmental objective.”[65] In short, the due process violation is unfair based upon the verbiage of the law itself. By way of example, two individuals are both charged with possession of cocaine. One of the accused has powder cocaine and the other has crack cocaine. Everyone within the criminal justice system recognizes that both accused are in possession of the same drug – cocaine (albeit a different form). Unfortunately, the statute which the accused is charged with distinguishes powder cocaine convictions as a lesser offense than a crack cocaine conviction. At sentencing the accused convicted of powder cocaine receives 10 years less than their counterpart who is convicted on crack cocaine. Sometimes compounding a substantive due process violation is the disproportionate impact it has on Black and brown communities evidenced in the language of the statute itself.

Substantial Due Process[66]

The Fourteenth Amendment guarantee of Substantive Due Process was first used to protect the right of a private business to make contracts. The Supreme Court, in Lochner v. New York (1905), struck down a New York State law that prohibited bakeries from from employing people for more than ten hours a day, or to require employees to work more than sixty hours in a week. The Court said that the right of a private business to make contracts was a fundamental liberty protected by the Fourteenth Amendment and its Due Process clause, and this law interfered with that liberty.[67] Substantive Due Process became the basis of many of the Court’s most controversial rulings protecting individuals, not businesses, rulings that established a right to privacy, a right to interracial marriage, a right to abortion, and a right to same sex marriage. In each case, the Court ruled that a law had interfered with the exercise of a fundamental liberty.[68]

d. Right to equal protection of the law

nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Thus, because the conversation surrounding citizen’s rights is fluid, it must include the current clause to be complete. Equal protection of the law was thought to be foundational in correcting so many wrongs with those who were deemed inhumane, therefore not citizens and thus stripped of all citizen’s rights. Although the phrase is a familiar phrase which endured every version of its drafting, the Framers who introduced this phrase in the Fourteenth Amendment did not envision the same meaning. Similar to our current struggles with Constitutional interpretation of verbiage, proper words to convey our thoughts, and finally what definitions we attribute to the word choice presented, the Framers also dealt with these issues regarding the Fourteenth Amendment. Their thoughts which converged on the inclusion of this clause into the final draft did not necessarily have the same meaning for each Framer. Thus, for our purposes we will adopt the meaning attributed from our esteemed legal resource – Black’s Law Dictionary. Black’s emphasizes the Fourteenth Amendment by stating that it is “[t]he constitutional amendment, ratified in 1868, whose primary provisions effectively apply the Bill of Rights to the states by prohibiting states from denying due process and equal protection and from abridging the privileges and immunities of U.S. citizenship.[69] Furthermore, “[i]n today’s Constitutional jurisprudence, equal protection means legislation which discriminates must have a rational basis for doing so.[70] And if the legislation affects a fundamental right (such as the right to vote) or involves a suspect classification (such as race), it is unconstitutional unless it can withstand strict scrutiny.”[71]

To this end, important concepts have been raised by parties within cases to encourage the Supreme Court of the United States to weigh in on the direct effect of the Equal Protection Clause. Recall, in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the court confirmed the widely held belief and law of “separate, but equal” rights for White and Black facilities. In this case, the doctrine was applied to a train. The court explained that the separation of whites and blacks is Constitutional and, more importantly, did not violate the fourth part of §1 of the Fourteenth Amendment.[72] Separate-but-equal doctrine is defined as “[t]he now-defunct doctrine that African-Americans could be segregated if they were provided with equal opportunities and facilities in education, public transportation, and jobs.”[73] It would take more than 60 years in 1954 for a new interpretation of this section to emerge. This new mentality emerged as a result of the composition of the court as well as the increase in the civil rights protests and activities of the country. Specifically, the unexpected death of Chief Justice Fred Vinson Jr. prompted President Dwight Eisenhower to nominate then California Governor Earl Warren to replace Vinson.[74]

Information for timeline[75]

This helped build the foundation for the Brown v. Topeka Board of Education (1954) decision. Chief Justice Warren would write the unanimous decision, which stated that segregation in public schools is “inherently unequal” and explained in non-legal language why he felt this practice produced and reinforced an inferiority complex in the Black children who were marginalized and dismissed within the public schools due to this law.[76] In fact, President Eisenhower was forced to use troops to protect those who engaged in this Constitutional action. “When Governor [Orval] Faubus ordered the Arkansas National Guard to surround Central High School to keep the nine students from entering the school, President Eisenhower ordered the 101st Airborne Division into Little Rock to insure the safety of the ‘Little Rock Nine’ and that the rulings of the Supreme Court were upheld.”[77] In fact, this was the first time troops were deployed to protect Blacks since the Reconstruction Era. Ultimately, President Eisenhower would sign the Civil Rights Act of 1957.[78]

SCOTUS would continue emphasizing the belief that the United States Constitution is a living, breathing document which is adaptable and adoptable to expand and respond to current events. This led the Warren Court to have much progress in the areas of race, criminal justice, political procedures, as well as church and state.[79] Additionally, this expansion was questioned as it relates to interracial marriage in Loving v. Virginia (1967).[80] In Loving, Chief Justice Warren evidenced the breadth and depth of the Equal Protection Clause and the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The court explained that marriage is a fundamental right which can not be dictated by parameters based solely on race and held that “the freedom to marry, or not marry, a person of another race resides with the individual, and cannot be infringed by the State.”[81]

Another important equal protection case was decided in 2023, Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard. The U.S. Supreme Court held, in a 6-3 vote, that race-based affirmative action programs in college admissions processes at Harvard College (a private institution) and the University of North Carolina (public) both violate Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which bars racial discrimination by government entities.[82]

Affirmative Action is defined by Black’s Law Dictionary as

“1. The practice of selecting people for jobs, college spots, and other important posts in part because some of their characteristics are consistent with those of a group that has historically been treated unfairly by reason of race, sex, etc.; specif., a preference or decision-making advantage given to members of a racial minority that has historically been subjected to systemic discrimination.

2. An action or set of actions intended to eliminate existing and continuing discrimination, to redress lingering effects of past discrimination, and to create systems and procedures to prevent future discrimination, all by taking into account individual membership in a minority group so as to achieve minority representation in a larger group.”[83]

The decision severely limited, if not effectively ended, the use of affirmative action in college admissions. Chief Justice Roberts, writing for the majority, held that a student “must be treated based on his or her experiences as an individual—not on the basis of race.” Justice Sotomayor, who once called herself “the perfect affirmative action baby,”[84] emphasized in her dissent that the majority’s decision had rolled “back decades of precedent and momentous progress” and “cemented a superficial rule of colorblindness as a Constitutional principle in an endemically segregated society.”

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

Brown v. Board (1954) would take two cases, Brown I and Brown II, army troops, and nine brave Black students – “The Little Rock Nine” to fight the mental precedents of governments in Arkansas. However, the holding would not result in true school integration until the 1970’s, and was then met with fierce resistance. Today, nearly half of all black students attend majority black schools, with over 70% in high-poverty school districts. New York is the most segregated state: two-thirds of its black students attend schools that are less than 10% white. Schools remain segregated mostly because their neighborhoods are segregated.[85]

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT XIV

Section 2

a. Right for each individual to be treated as whole person

Representatives shall be apportioned among the several States according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each State, excluding Indians not taxed.

Upon first glance, this portion of §2 of the Fourteenth Amendment seems to address and eradicate all discrepancies between persons who are not considered a whole person. Specifically, this section addresses a previous section of Art. I, §2, cl. 3 of the original Constitution. This section of the Fourteenth Amendment repealed this clause known as the Three-Fifths Compromise. This compromise previously counted African slaves as three-fifths of a person as opposed to a whole person. This new approach may appear to work on behalf of slaves; however, this section worked for the purpose of apportioning congressional representation. Ultimately, counting the previously enslaved as whole persons provided more representation for their states, while not necessarily providing more human rights for Blacks. Most important is that this section still excluded Natives or Indigenous people from this new representative apportionment.

b. Right to Vote

But when the right to vote at any election for the choice of electors for President and Vice-President of the United States, Representatives in Congress, the Executive and Judicial officers of a State, or the members of the Legislature thereof, is denied to any of the male inhabitants of such State, being twenty-one years of age, and citizens of the United States, or in any way abridged, except for participation in rebellion, or other crime, the basis of representation therein shall be reduced in the proportion which the number of such male citizens shall bear to the whole number of male citizens twenty-one years of age in such State.

Legally, this section also guaranteed that all male citizens over age 21, regardless of landownership or race, had a right to vote. Operationally, we understand that not all male citizens had the right to vote. This did not include Blacks or Native males. Therefore, this remains contentious within the states. As always this section does provide exceptions. Males who are deemed to be in “rebellion or crime” are constitutionally allowed to be disenfranchised. Further this disenfranchisement may be extended based upon those who maintain court costs and fines in some jurisdictions according to their state constitutions.[86] Disenfranchisement is important as it works to destroy true democracy. Furthermore, disenfranchisement is defined as “[t]he act of taking away the right to vote in public elections from a citizen or class of citizens.”[87]

Operationally, the southern states continued to deny Black and Native men the right to vote using the laws known as the “Jim Crow” laws. These laws “represented a formal, codified system of racial apartheid that dominated the American South for three quarters of a century beginning in the 1890s.”[88] Unfortunately, these laws encompassed every area of life from “White Only” restrooms to heightened voter disenfranchisement. Thus, this section addressed an important concern which would be litigated for many years going forward.

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT XIV

Section 3

Right Against Congress

No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice-President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.

This section gives Congressional authority to prevent those who are public officials who seek to take an oath in their position, from taking office if they are confirmed to be a part of an insurrection or rebellion against the Constitution. “The intent was to prevent the president from allowing former leaders of the Confederacy to regain power within the U.S. government after securing a presidential pardon.”[89] Congress may overcome this issue with a two-thirds majority vote; therefore, an exception exists even for those who were actively engaged in insurrection or rebellion from holding office. This section of the Fourth Amendment leads the reader to consider the Insurrection which occurred at the Capitol on January 6, 2021. It appears that even if Congress could point to a member of Congress who engaged in this tragic event, only a vote of two-thirds of Congress is needed to overcome this disability (if it were raised). Hence, many members of Congress believe an investigation which leads to action in this case could be a waste of taxpayers’ money, while undermining the taxpayers’ confidence.

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT XIV

Section 4

Right Against Governmental Assistance with Public Debt

The validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law, including debts incurred for payment of pensions and bounties for services in suppressing insurrection or rebellion, shall not be questioned. But neither the United States nor any State shall assume or pay any debt or obligation incurred in aid of insurrection or rebellion against the United States, or any claim for the loss or emancipation of any slave; but all such debts, obligations and claims shall be held illegal and void.

This section points to the mounting debt incurred by those states who engaged in war against the United States of America. In fact, those states which left to form the Confederacy had a right to confirm their remaining debt from war, but lacked the ability to have the United States pay said debt. As the Confederacy lost the war, it was important for those who remained in the federal government not to allow financing for the debts which were in question, such as for slavery.[90]

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT XIV

Section 5

Right to Enforcement of Fourteenth Amendment

The Congress shall have the power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.

As previously stated earlier, the verbiage of the Fourteenth Amendment is a repeat of a similar version of §2 of the Thirteenth Amendment. Again, Congress is granted the power to ensure that the controversial Fourteenth Amendment is properly enforced using all available legislation. This verbiage in the Constitutional amendment enabled proper enforcement power by appropriate legislation. Similar verbiage can be seen in the Thirteenth, Fifteenth, Nineteenth, Twenty-third, Twenty-fourth, and Twenty-sixth Amendments.

Amendment XV

Passed by Congress February 26, 1869. Ratified February 3, 1870.

Section 1

The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

Section 2

The Congress shall have the power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

INTRODUCTION TO AMENDMENT XV

Recall under the original Constitution and for much of American history, only landowning white males over 21 years old were legally allowed to vote. Although the right to vote cannot be denied based upon race, religion, sex, disability, or sexual orientation, the right still remains highly politicized and polarized when the voter is 18 years old.[91] Furthermore, disenfranchisement continues to occur with some states exhibiting tactics to reduce as opposed to increase enfranchisement. This topic is further explored in the analysis section of Amendment XV. Finally, all states require registration for voting, except North Dakota.[92] The Fifteenth Amendment is specifically dedicated to protecting the right of all citizens to vote, regardless of race.[93]

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT XV

Section 1

a. Right to Vote for Every Male over the Age of 21

The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

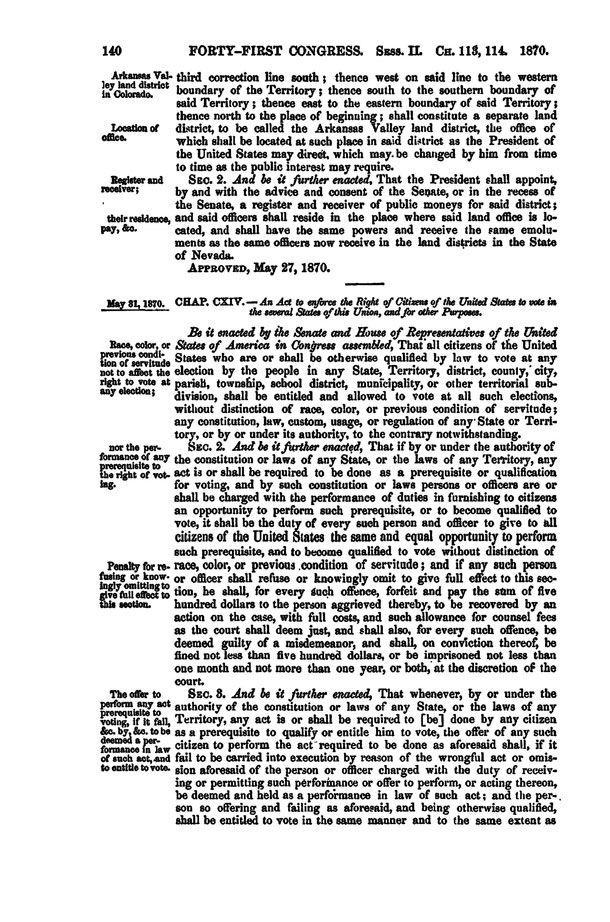

After slaves became humans (Thirteenth Amendment) and these humans became citizens (Fourteenth Amendment), the Fifteenth Amendment granted male citizens over the age of 21 Constitutional protections of voting. To support this amendment’s passage, Nevada Senator William Stewart provided direction and expertise as the Fifteenth Amendment progressed through the Senate.[94] Unfortunately, this well-intentioned amendment left Confederate states the opportunity to continue to block the previously identified males with new ways to disenfranchise those who were impacted the most by the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. Particularly, this provision could not prevent literacy tests, poll tax, and other inequitable means to support voter disenfranchisement. These practices would persist for almost 100 years until the Twenty-fourth Amendment and the Voters Right Act of 1965.“The Enforcement Acts (also referred to as Civil Rights Acts) were three bills passed by the Federal government in 1870 and 1871 that were intended to protect African American rights to vote, hold office, be on juries, and have protection under the law.”[95]

Section 2

b. Right to Enforcement of the Fifteenth Amendment

The Congress shall have the power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

The Enforcement Act of 1870[96]

Congress believed additional enforcement would be necessary. Therefore, this Constitutional amendment enabled proper enforcement power by appropriate legislation. Similar verbiage can be seen in the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, Nineteenth, Twenty-third, Twenty-fourth, and Twenty-sixth Amendments. One manifestations of this additional legislation included the Enforcement Act of May 1870, Second Force Act of February 1871, and the Third Force Act of April 1871. Each of these Enforcement acts were in direct response to the enforcement verbiage of Amendment Thirteen, Amendment Fourteen, and Amendment Fifteen as well as the Civil Rights Act of 1866.[97] Collectively, these acts became known as the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) Acts. These members of the KKK continued to “terrorize black citizens for exercising their right to vote, running for public office, and serving on juries.”[98] Congress passed the second attempt to diminish these attacks “a series of Enforcement Acts in 1870 and 1871 (also known as the Force Acts) to end such violence and empower the president to use military force to protect African Americans.”[99] Although the Force Acts provided some form of relief for African-Americans, “the end of formal Reconstruction in 1877 allowed for a return of largescale disenfranchisement of African Americans.”[100]

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 (the “VRA”), passed by Congress at the height of the Civil Rights movement in the United States, outlaws any “voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, ” including literacy tests, tests for educational achievement and understanding, proof of “good moral character,” and vouchers for qualification as a registered voter, that deny the right to vote on account of race or color.[101] The VRA provides that States and localities where less than 50% of the persons of voting age are registered, must receive the approval of the district court of the District of Columbia or of the U.S. Attorney General (“preclearance”) prior to implementing any changes in election laws.[102] The VRA also authorizes the appointment of federal voting examiners to register voters when the Attorney General deemed that was necessary to the enforcement of the Fifteenth Amendment.[103] The Supreme Court affirmed its constitutionality in South Carolina v. Katzenbach (1966).[104] The VRA was extended in 1970 and again in 1975 to 1982, then extended again, this time for 25 years.[105] In 2006, Congress extended the VRA for another 25 years. The 1975 extension added an amendment, explicitly covering Hispanic, Asian-American, Native American, and Native Alaskan voters.[106]

George W. Bush, 43rd President of the United States (2001-2009), signing the 2006 extension of the Voting Rights Act, joined by Democratic and Republican members of Congress for the signing ceremony. The extension passed overwhelmingly in the House of Representatives, and 98-0 in the Senate.[107]

The effect of the Voting Rights Act was profound. Nearly as many Black people registered to vote in southern states in its first five years as in the entire previous century combined.[108] In Mississippi, African-American registration jumped from 7% in 1964, to 59% four years later, and 71% by 1998. The law changed the South, and for the first time opened the way for a truly multiracial democracy in the United States.[109]

However, in 2013, the Supreme Court in Shelby County v. Holder, by a 5-4 majority vote, invalidated Section 4 of the VRA, which had specified a formula for singling out certain States and counties for preclearance review by the U.S.[110] Writing for the slim majority, Chief Justice Roberts held that either Congress must revise the Section 4 formula, or that the Justice Department must independently prove that a State or county attempted to dilute the voting power of minorities.[111] He declared that the continued use of a formula was “based on 40-year-old facts” and that the country had changed, because more African-Americans vote and are elected to office today than fifty years ago.[112] Therefore, he found Section 4 of the VRA to be unconstitutional. In dissent, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg arguing that the majority had been shortsighted in saying Section 4 was no longer needed. In fact she famously remarked, “It is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.”[113] For further information on this topic, refer to Introduction to Amendment XXIV later in this chapter.

Amendment XXIV

Passed by Congress August 27, 1962. Ratified January 23, 1964.

Section 1

The right of citizens of the United States to vote in any primary or other election for President or Vice President, for electors for President or Vice President, or for Senator or Representative in Congress, shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any State by reason of failure to pay poll tax or other tax.

Section 2

The Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

INTRODUCTION OF AMENDMENT XXIV

Unfortunately, the verbiage of Amendment XIII, Amendment XIV, and Amendment XV did not end the struggles for voting, especially women and African-Americans.

“Because of widespread discrimination in many states, including the use of poll taxes, grandfather clauses, and literacy tests, and other more violent means, African Americans were not assured basic voting rights until President Lyndon Baines Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act in 1965.”[114]

The Voting Rights Act in 1965 addressed discriminatory voting practices adopted in many southern states after the Civil War, including literacy tests, poll taxes, and grandfather clauses as a prerequisite to voting. Unfortunately, the Voting Rights Act in 1965 continues to face opposition.

In 2023, the Supreme Court decided two cases that promise to have a far-reaching impact on the ability of African-Americans to vote. In Allen v. Milligan (2023), voters and pro-voting groups had filed two lawsuits, arguing that Alabama’s congressional map diluted the voting strength of Black Alabamians, violating Section 2 of the VRA.[115] The Court ruled 5-4 in favor of the Plaintiffs, finding that Section 2 had been violated, and most importantly, leaving Section 2 of the VRA intact. Other States, such as Louisiana, that had aimed to limit the voting ability of Blacks have curtailed their plans, in light of the decision in Allen v. Milligan.[116]

The second case is Moore v. Harper (2023) in which the North Carolina Supreme Court had struck down the State’s congressional map for violating the state constitution.[117] Republican State legislators appealed the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court, invoking a new idea, the Independent State Legislature theory (ISL). They argued that the Elections Clause of the U.S. Constitution (Article I, Section 4) grants State legislatures the sole authority to enact congressional maps, free of judicial review by the State courts.[118] The Supreme Court voted 6-3 against the legislators, rejecting the ISL theory. Chief Justice Roberts, writing for the majority, ruled that the Elections Clause “does not insulate state legislatures from the ordinary exercise of state judicial review.”[119]

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT XXIV

Section 1

a. Right Against Poll Tax

The right of citizens of the United States to vote in any primary or other election for President or Vice President, for electors for President or Vice President, or for Senator or Representative in Congress, shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any State by reason of failure to pay poll tax ….

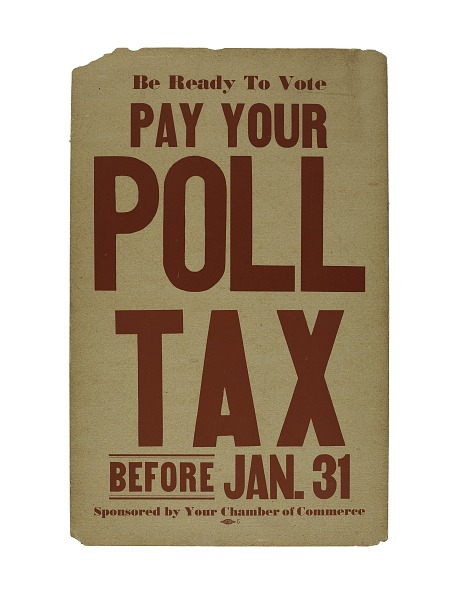

Twenty-Fourth Amendment, Pay Your Poll Tax[120]

The conversation surrounding elections, electors and the entire process was called into question with the 2020 Presidential Election with Republican Donald J. Trump and Democrat Joseph R. Biden, Jr. On every side and within every cycle, on one thing all political activists agreed. Competing pundits across the political spectrum each believe that democracy is being threatened but for very different reasons. Democrats believe Republicans and those who support President Trump have irrationally and unconstitutionally made claims of voter fraud in jurisdictions mostly comprised of Black and Brown people. These specific areas include counties in Pennsylvania, Florida, Michigan, Georgia and heavily populated areas of Black voters.[121]

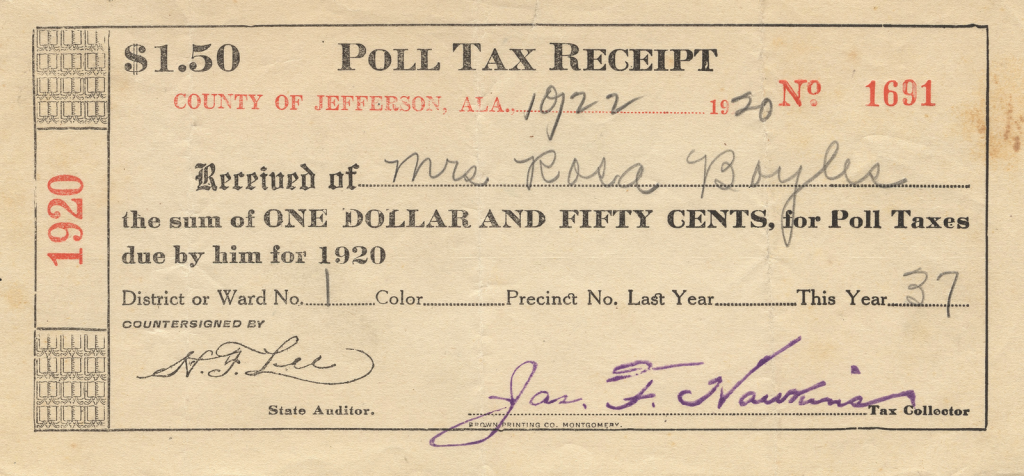

Poll tax receipt[122]

In fact, Former President Trump continues to cast doubt on these votes, specifically in Black communities.[123] On the other hand, Republicans overwhelmingly believe that Former President Trump endured an unfair year in 2020. This unfairness stemmed from voter fraud, mail-in ballot fraud, poll watchers denied access, as well as votes being inaccurately counted.[124] More than 100 lawsuits were filed unsuccessfully contesting the 2020 election processes, vote counting and the voter certification process in multiple states and the District of Columbia, as well as two presidential recounts were conducted.[125]

This is of particular note in this section because Black men did not receive the right to vote with great limitations until the Fifteenth Amendment; however, the poll tax indicated in the Twenty-fourth Amendment, ratified in 1964, continues to be exploited. Therefore, the country remains in turmoil regarding racial inequity and disparities among voters who were forced to make a plan to vote, endure weather irregularities, a health pandemic as well as a racial pandemic.

b. Right Against Other Tax

… or other tax.

To date, there are now more than 300 bills and laws that have been offered which may be categorized as other taxes. This includes Georgia laws containing provisions whereby bringing water and food to those standing in voting lines was deemed illegal.[126] Additionally, the law reduced or eliminated Sunday voter drives and early voting. Finally, the laws change the structure and ability of a new appointee to overturn local voting results.[127] These efforts have worked to disenfranchise Black and Brown voters just as hurdles were placed in the way of previous efforts of disenfranchisement of Black and Brown voters.[128] These efforts have led to bills and laws for inappropriate and irrelevant actions to reduce voter turn out.

Many persons, entities as well as organizations have responded with solidarity statements, boycotts, and other intentional responses. However, several actors and other famous activists have chosen to address the matter with a dollar and cents approach. As seen to the left with Will Smith and Director Antoine Fuqua. Opponents of the bills and laws are convinced that using their First Amendment freedoms and rights will bolster their claim of the unfair treatment of Georgia Senate Bill 202 signed into law by Governor Brian Kemp. World renowned actor, Will Smith and Director Antoine Fuqua are working on a film entitled Emancipation.[129] Ironically, this film is set in the 1860s and follows a man, played by Will Smith, who escaped the harsh treatment of a slave plantation to fight for his interest with the Union army. Specifically, Fuqua and Smith stated “At this moment in time, the Nation is coming to terms with its history and is attempting to eliminate vestiges of institutional racism to achieve true racial justice. We cannot in good conscience provide economic support to a government that enacts regressive voting laws that are designed to restrict voter access. The new Georgia voting laws are reminiscent of voting impediments that were passed at the end of Reconstruction to prevent many Americans from voting. Regrettably, we feel compelled to move our film production work from Georgia to another state.”[130]

Section 2

c. Right to Enforcement of Twenty-fourth Amendment

The Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

As previously stated, Congress is granted the power to ensure that the controversial Twenty-fourth Amendment is properly enforced using all available legislation. This verbiage in the Constitutional amendment enabled proper enforcement power by appropriate legislation. It mirrors the language found in the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, Nineteenth, Twenty-third, and Twenty-sixth Amendments.

Therefore, the above amendments provided more than additional rights to groups of individuals who were otherwise disregarded. Through their sections and parts, forgotten Americans received humanity, citizenship, and ultimately voting rights. Therefore, the pursuit of equity is one that has only been progressed with litigation, Constitutional amendments, and grassroots efforts.

Critical Reflections:

1. Is mass incarceration a form of slavery or involuntary servitude? Explain.

2. Might Congress validly allow disabled citizens to sue states for denial of adequate access to state facilities such as: courtrooms, voting booths, jail facilities, legislative chambers, hearing rooms, and sports arenas?

3. Is “voter ID,” that is, requiring voters to obtain and present a valid government-issued identification card, allowed under the Twenty-Fourth Amendment? Why or why not?

4. Watch 13th here which is a documentary on the Thirteenth Amendment. Which activists are pictured in the documentary? What do they discuss? Who do you see from the political realm? What is their focus? Do you agree with DuVernay’s depiction?

5. Chief Justice Roger Taney, in the 1857 Dred Scott decision, held that men of African descent were “so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect…the Negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit.” After viewing the photo and caption below, and reading the short Time Magazine article about it here, answer this question: In modern-day America, is true reconciliation between descendants of slaveholders and descendants of slaves an achievable goal?

- Gauthier, J. H. S. (2020, December 17). Censuses of American Indians - history - U.S. Census Bureau. Censuses of American Indians. https://www.census.gov/history/www/genealogy/decennial_census_records/censuses_of_american_indians.html ↵

- Gibson, C., & Jung, K. (2002, September). Historical Census Statistics on Population Totals by Race, 1790 to 1990, and by Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, for the United States, Regions, Divisions, and States. U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/working-papers/2002/demo/POP-twps0056.pdf ↵

- United States Census. (n.d.). Population of the United States in 1860. United States Census Dicennial 1860. Retrieved April 10, 2021, from https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1860/population/1860a-02.pdf ↵

- Netflix. (2020, April 17). 13TH | FULL FEATURE | Netflix [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=krfcq5pF8u8 ↵

- U.S. senate: Landmark legislation: Thirteenth, fourteenth, & fifteenth amendments. (2021, January 11). United States Senate. https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/generic/CivilWarAmendments.htm ↵

- History.com Editors. (2021, March 16). Native american history timeline. HISTORY. https://www.history.com/topics/native-american-history/native-american-timeline ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Native American and Indigenous Peoples FAQs. (n.d.). UCLA Equity, Diversity & Inclusion. https://equity.ucla.edu/know/resources-on-native-american-and-indigenous-affairs/native-american-and-indigenous-peoples-faqs/#:~:text=The%20U.S.%20Census%20defines%20American,definition%2C%20citizens%20of%20their%20federally. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Lynch, H. (n.d.). African americans | history, facts, & culture. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved April 18, 2021, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/African-American ↵

- Slavery and the Making of America. Timeline | PBS. (2004). Slavery and the Making of America. https://www.thirteen.org/wnet/slavery/timeline/1641.html ↵

- SLAVERY, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Notice of slave sale, “Public sale!. . .consisting of three slaves. . .” Public domain. NYPL Digital Collections. ↵

- $200 reward: Poster for the Return of Formerly-Enslaved People, October 1, 1847. Public domain. Wikimedia Commons. ↵

- Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896) ↵

- Id. ↵

- Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 US 483 (1954). ↵

- MANUMISSION, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024) ↵

- MANUMISSION, 2024. ↵

- Manumission by slave. (2017, November 16). The Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition. https://glc.yale.edu/VoicesFromTheArchive/WhatdidFreedomMean/Manumission-By-Slave. ↵

- Prince. (2017, November 16). The Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition. https://glc.yale.edu/VoicesFromTheArchive/WhatdidFreedomMean/Manumission-By-Slave/Prince. ↵

- SLAVERY (2019). ↵

- Lieberman, J. (1888). Evolving constitution: How supreme court has ruled on issues from abortion to zoning. Random House Reference. ↵

- McPherson, J. (2021, April 16). A brief overview of the american civil war. American Battlefield Trust. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/brief-overview-american-civil-war. ↵

- McPherson, J. (2021, April 16). A brief overview of the american civil war. American Battlefield Trust. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/brief-overview-american-civil-war ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- McPherson, 2021. ↵

- Gross, A., & Upham, D. (n.d.). Interpretation: Article IV, Section 2: Movement of persons throughout the union | the national constitution center. Interactive Constitution. Retrieved May 31, 2021, from https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/interpretation/article-iv/clauses/37 ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Healy, George. Abraham Lincoln. Public domain. Wikimedia Commons. ↵

- History.com Editors. (2020a, June 19). Thirteenth amendment. HISTORY. https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/thirteenth-amendment#section_1 ↵

- History.com Editors. (2021a, January 25). Emancipation proclamation. HISTORY. https://www.history.com/topics/american-civil-war/emancipation-proclamation ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- RayneVanDunem. U.S. states which prohibit slavery or involuntary servitude in their state constitutions [updated June 2023]. CC BY-SA 4.0. Wikimedia Commons. ↵

- SERVITUDE, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- PEONAGE, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Interpretation: The thirteenth amendment | the national constitution center. (n.d.). National Constitution Center. Retrieved April 17, 2021, from https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/interpretation/amendment-xiii/interps/137#:%7E:text=Section%20Two%20of%20the%20Thirteenth%20Amendment%20empowers%20Congress%20to%20%E2%80%9Cenforce,conduct%20than%20just%20coerced%20labor ↵

- Bailey v. Alabama, 219 U.S. 219 (1911). ↵

- U.S. v. Kozminski, 487 U.S. 931 (1988). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Greene, J., & McAward, J. M. (2016, December 6). A Common Interpretation: The Thirteenth Amendment. National Constitution Center. https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/blog/a-common-interpretation-the-thirteenth-amendment ↵

- United States Senate. (2021, January 11). U.S. senate: Landmark legislation: Thirteenth, fourteenth, & fifteenth amendments. https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/generic/CivilWarAmendments.htm ↵

- United States Senate. (2021, January 11). ↵

- 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Civil Rights (1868). (2022, February 8). National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/14th-amendment#:~:text=No%20State%20shall%20make%20or,equal%20protection%20of%20the%20laws. ↵

- 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Civil Rights (1868), 2022. ↵

- Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 US 393 (1857). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Douglass, F. (2022). Frederick Douglass: Speeches & Writings (LOA #358). Library of America. ↵

- Warren, George Kendall. Fredrick Douglass (circa 1879) [cropped]. Public domain. Wikimedia Commons. ↵