Chapter 2 – The Original United States Constitution & Its History – Part II

Article III, Article IV, Article V, Article VI, and Article VII

Richard J. Forst and Tauya R. Forst

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

2.1 List the sources of the law.

2.2 Define jurisdiction.

2.3 Identify the structure of the federal and state court system.

2.4 Evaluate the procedure for selection of judges and justices.

2.5 Explain how judicial review originated.

2.6 Summarize the landmark case that defined the powers of the judicial review in Marbury v. Madison.

2.7 Explain the process of Amendment creation and ratification, including the Article that governs the process.

KEY TERMS

Certiorari Jurisdiction

Checks and balances Privileges and Immunities Clause

Codes Ratification

Common Law Stare Decisis

Full Faith and Credit Clause Statute

Guarantee Clause Supremacy Clause

Judicial Review United States Constitution

INTRODUCTION OF ARTICLE III

As previously stated, Article III of the United States Constitution also known as the judicial branch, provides checks and balances on the Legislative and Executive branches of government. “Ultimate judicial power is given to the Supreme Court of the United States; there is no higher court to which an appeal may be taken.”[1] Because of this ultimate judicial authority, the Supreme Court is often referred to as the “Court of Last Resort” as it is the highest court within the federal system and hears cases appealed from the state supreme courts as well.[2] As the Constitution evolved, the amendments had a profound effect on the Articles. As a result, we will outline how each article evolved as well as how it affected the execution of the government based upon the ratification of the amendments.

The law is an interesting mixture of past rules and common law (judicial decisions), codes, statutes, constitutions and case law. All of these sources tend to impact the law in a different manner.

Common law was originally derived from English judicial decisions. The collection of these judicial decisions is usually drawn as a comparison to statutory law. When lawmakers seek to give common law permanence, the process of converting common law into a statute begins.

Common law was thoroughly vetted by Justice Clarence Thomas in Gamble v. United States (2019).[3] In this case, the court granted certiorari (review) to discuss the defendant’s double jeopardy claim. The defendant was found guilty in the Alabama state court for felon-in possession charges. After Gamble was convicted, he was charged with a similar offense within the federal statute. The United States insisted that charging an individual in both federal and state court does not violate double jeopardy because double jeopardy only applies when you are being tried for the same crime in the same jurisdiction. In Gamble (2019), Justice Thomas explores both common law and stare decisis. First, he addressed the parameters of stare decisis when he stated, “We should restore our stare decisis jurisprudence to ensure that we exercise mer[e] judgment, which can be achieved through adherence to the correct, original meaning of the laws we are charged with applying. In my view, anything less invites arbitrariness into judging.”[4]

Typically, a statute is “[a} law enacted by a legislative body; specifically, legislation enacted by any lawmaking body, such as a legislature, administrative board, or municipal court.”[5] The federal legislative body, Congress, creates federal statutes, or “codes.” Federal codes are applicable to all areas with federal jurisdictions. Black’s Law Dictionary defines jurisdiction as, “2. A court’s power to decide a case or issue a decree.”[6] Whereas the highest law of the land, the United States Constitution, comprises three parts: The Preamble, The Articles, and The Amendments, each one of these legal constructs impacts how we view the law and how justice is dispensed. The famed French political scientist, Alexis De Tocqueville, wrote about the American political and social system as he observed it in the 1830s. He wrote: “There is almost no political question, in the United States, that does not sooner or later resolve itself into a judicial question.”[7]

Click here for a visual for how cases proceed through the Illinois court system.

Click here for a visual for how cases proceed through the United States Federal court system.

Article III

*Highlighted sections indicate changes identified in other parts of the Constitution of the United States. Signed in convention September 17, 1787. Ratified June 21, 1788. A portion of Article III, Section 2, was changed by the 11th Amendment.

Section 1

The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish. The Judges, both of the supreme and inferior Courts, shall hold their Offices during good Behaviour, and shall, at stated Times, receive for their Services, a Compensation, which shall not be diminished during their Continuance in Office.

Section 2

The judicial Power shall extend to all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made, or which shall be made, under their Authority;–to all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls;–to all Cases of admiralty and maritime Jurisdiction;–to Controversies to which the United States shall be a Party;–to Controversies between two or more States;–between a State and Citizens of another State;–between Citizens of different States;–between Citizens of the same State claiming Lands under Grants of different States, and between a State, or the Citizens thereof, and foreign States, Citizens or Subjects.

In all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, and those in which a State shall be Party, the supreme Court shall have original Jurisdiction. In all the other Cases before mentioned, the supreme Court shall have appellate Jurisdiction, both as to Law and Fact, with such Exceptions, and under such Regulations as the Congress shall make.

The Trial of all Crimes, except in Cases of Impeachment; shall be by Jury; and such Trial shall be held in the State where the said Crimes shall have been committed; but when not committed within any State, the Trial shall be at such Place or Places as the Congress may by Law have directed.

Section 3

Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying War against them, or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort. No Person shall be convicted of Treason unless on the Testimony of two Witnesses to the same overt Act, or on Confession in open Court.

The Congress shall have Power to declare the Punishment of Treason, but no Attainder of Treason shall work Corruption of Blood, or Forfeiture except during the Life of the Person attainted.

Judicial Branch

ANALYSIS of ARTICLE III

Section 1

The judicial power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish. The Judges, both of the supreme and inferior courts, shall hold their offices during good Behavior, and shall, at stated times, receive for their Services, a Compensation, which shall not be diminished during their Continuance in Office.

17th Chief Justice John Roberts of the United States, Pictured Above is Roberts Court Formal Photo dated 083122[8]

The Constitution itself states that we will have a Supreme Court. This Court is separate from both the legislative (Congress) and the executive (the President) branches. Based upon Article III, Congress establishes all other federal courts. In 1789, Congress created the first federal judiciary, including the Supreme Court – with six Justices. Since the first Supreme Court of the United States took the bench, the number of justices has changed six times with the current composition taking effect in 1869 and remaining as such. The court’s composition included as few as six justices and as many as 10.[9] This composition includes one Chief Justice and eight Associate Justices. Currently serving the court is the 17th Chief Justice, Chief Justice John Roberts.

He is joined by the following eight Associate Justices in order of seniority:

- Associate Justice Clarence Thomas,

- Associate Justice Samuel Alito,

- Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor,

- Associate Justice Elena Kagan,

- Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch,

- Associate Justice Brett Kavanaugh,

- Associate Justice Amy Coney Barrett, and

- Associate Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson.

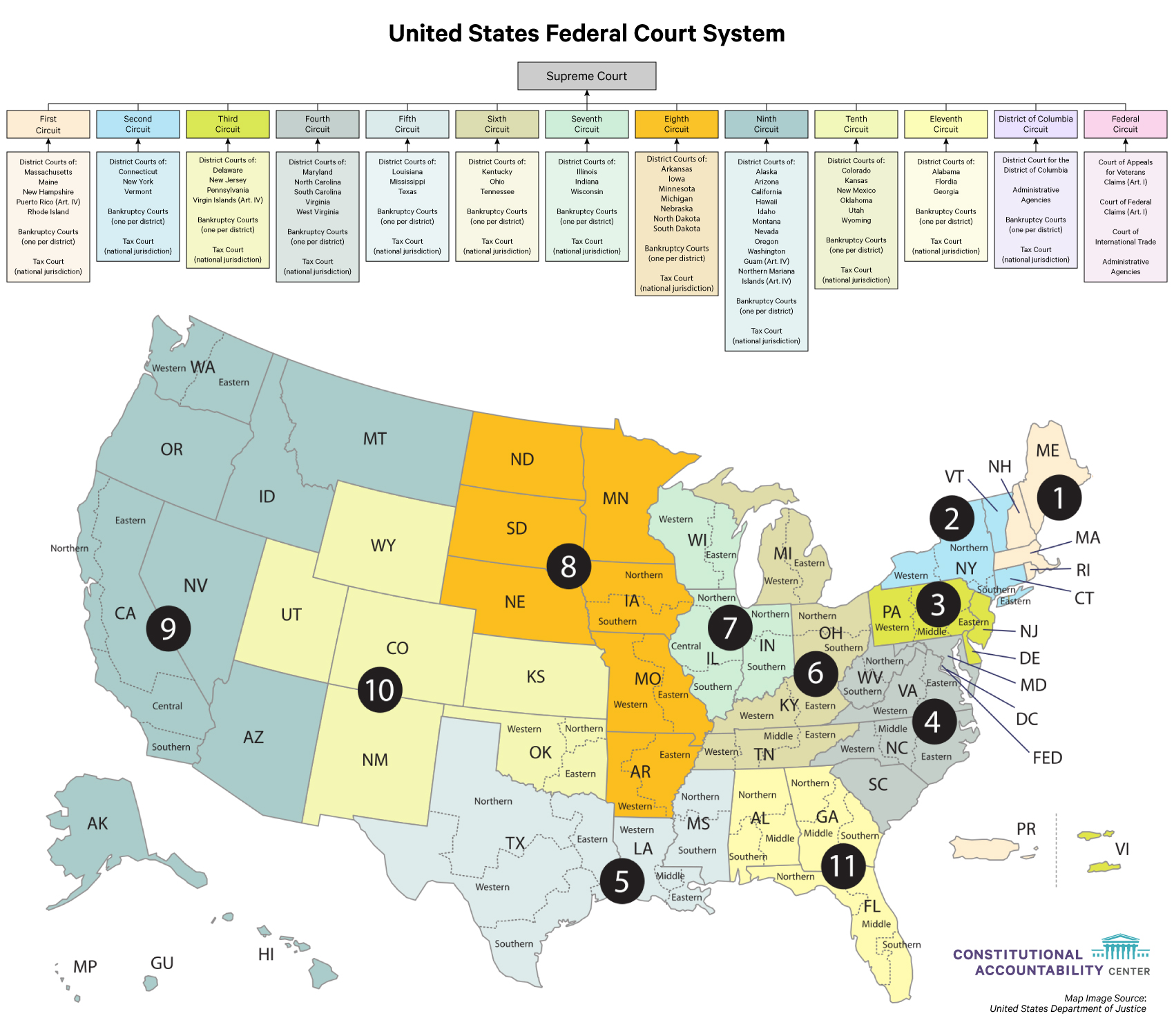

Additionally, Congress has increased the number of lower courts many times. For example, in 1901, Congress created space for about 100 federal judges; by 2001, that number was up to 850.[10]The lower courts consist of 94 federal district courts (the “trial courts”), and above the district courts but below the Supreme Court, 13 federal Courts of Appeals. (See link above for visual of how courts operate.) The 94 federal judicial districts are organized into 12 regional circuits, each of which has a Court of Appeals. The 13th has nationwide federal jurisdiction and hears specialized cases. The appellate court’s task is to determine whether or not the law was applied correctly in the trial court. Appeal courts consist of three judges and do not use a jury. State court systems are similarly organized.[11]

All federal judges and the Justices of the Supreme Court are appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate. The Framers of the Constitution were concerned that the federal government would not be effective unless it had courts to help enforce its laws. If processes were left to state courts, then the states that were hostile to the new federal government might thwart it at every turn.

Additionally, federal judges obtain their office through provisions set forth in Article II, which gives the President the power to “nominate” judges of the Supreme Court and lower courts, as well as provides the Senate the authority to “advise and consent.” The question for contemporary debate asks whether the Senate has an obligation to act on nominations in any particular way.[12]

For example, in 2016, Democratic President Barack Obama nominated Judge Merrick Garland to fill a vacancy on the Supreme Court of the United States.[13] However, in March 2021, President Joe Biden nominated him as the Attorney General (AG) of the United States. Under AG Garland, the 15000 employees of the AG’s office have made their mark: to uphold the rule of law, to keep our country safe, and to protect civil rights.”[14] Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, the Senate Majority Leader, refused to convene any committees to consider the nomination or to allow the nomination to come to the Senate floor for a vote. McConnell declared any appointment by the sitting President to be null and void. McConnell further explained that the next Justice should be chosen by the next president, to be elected later that year.[15] There was no precedent for such an action since the period around the Civil War and Reconstruction. The Court had to convene that October with only eight Justices, divided often and deadlocked at 4-4 on a number of issues.[16]

Thus, the individuals who become judges gain their office by virtue of the decisions of elected officials. But, once the judges are appointed, the Constitution insulates their independence. Article III, §1 protects all federal judges by providing job security, while supporting a non-diminished salary. “Thus, we speak of such judges as “life-tenured,” and some of them have sued (and sometimes won) when Congress has failed to provide them with cost-of-living increases or other salary benefits.”[17]

Congress could have used its power granted by the Constitution to grant wide powers to the federal courts that could not be limited or rescinded. However, the “anti-Federalists,” always fearful of a strong central government, either wanted no inferior federal courts at all below the Supreme Court or else wanted to give such courts as little jurisdiction as possible. They instead wanted original jurisdiction in most federal questions given to state courts, subject only to the appellate power of the Supreme Court. The final version of Article III was a political compromise which established a system of district and circuit courts. The courts’ accessibility and convenience, in comparison to similar state courts, was thus limited. State courts retain original jurisdiction over most legal disputes, such as over crimes committed within the states themselves.

Note: Article III does not provide a guaranteed budget for the federal courts.Federal courts are used as a check on the state courts. Recall Congress increased the number of federal judges over time, while expanding the federal courts’ personnel in 1960s by creating the office of “magistrate” (now called magistrate judge). Additionally, in the 1980s, the office of “bankruptcy judge” was established. These officials have dedicated courtrooms and do a great deal of judicial work; their numbers doubled the size of the lower federal court judicial personnel. After the Civil War, Congress sought to create a “federal presence” by building impressive federal courthouses (often combined with post offices). Today, upwards of 500 federal courthouses now dot the landscape.[18]

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

Alexander Hamilton, in Federalist No. 78 (“The Federalist Papers”), stated judicial independence “is the best expedient which can be devised in any government to secure a steady, upright, and impartial administration of the laws.”[19] Hence, federal judgeships are lifetime appointments, designed to exceed the terms of Presidents, Senators and members of the House of Representatives.

As recently as 1997, the Supreme Court further curbed the supremacy of the federal government by creating the “anti-commandeering rule,” a rule that prohibits Congress from requiring state officials to perform federal duties, in this case, to participate in Congress’s interim background-check program for firearms purchases.[20] The 5-4 decision in Printz v. United States (1997) held this provision of the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act violated the Tenth Amendment of the Constitution.[21]

In 2023, the Senate is considering imposing an ethics requirement on the Supreme Court known as the “Supreme Court Ethics, Recusal and Transparency Act.” The potential legislation comes amid allegations of ethics breaches among the justices and reports of luxurious vacations paid for by private benefactors. The justices on the Supreme Court are the only members of the federal judiciary not currently subject to ethics requirements, except what they themselves determine to self-impose. In July 2023, in an Opposite the Editorial Page Opinion (or an “op-ed”), Justice Alito stated “I know this is a controversial view, but I’m willing to say it. No provision in the Constitution gives them [Congress] the authority to regulate the Supreme Court–period.”[22] Meanwhile, two prominent Constitutional scholars, conservative former federal Judge J. Michael Luttig and liberal Harvard professor Laurence Tribe, stated Congress does have the power to impose a code of conduct for Supreme Court justices.[23] Others experts disagree. The disagreement is about the scope and extent of Congressional power over the Supreme Court granted in Article III of the Constitution.

ANALYSIS OF ARTICLE III

Section 2

The judicial Power shall extend to all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made, or which shall be made, under their Authority;—to all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls;—to all Cases of admiralty and maritime Jurisdiction;—to Controversies to which the United States shall be a Party;—to Controversies between two or more States;—between a State and Citizens of another State;—between Citizens of different States;—between Citizens of the same State claiming Lands under Grants of different States, and between a State, or the Citizens thereof, and foreign States, Citizens or Subjects.

In all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, and those in which a State shall be Party, the supreme Court shall have original Jurisdiction. In all the other Cases before mentioned, the supreme Court shall have appellate Jurisdiction, both as to Law and Fact, with such Exceptions, and under such Regulations as the Congress shall make.

The Trial of all Crimes, except in Cases of Impeachment; shall be by Jury; and such Trial shall be held in the State where the said Crimes shall have been committed; but when not committed within any State, the Trial shall be at such Place or Places as the Congress may by Law have directed.

United States Federal Court System[24]

Importantly, the Judiciary Act of 1789 defined the broad grant of jurisdiction from Article III in a relatively narrow way. The federal courts were granted no common-law jurisdiction except for criminal offenses against the United States. Diversity cases were limited by a requirement that the amount in dispute exceed $500.00 (no small amount in 1789), as most disputes between citizens of different states would not be heard in federal court. The effect was to direct most disputes to state courts where local officials could have more control over judicial appointments, jurisdiction, and the makeup of juries.[25]

The Supreme Court was feeble in its first decade. It had three Chief Justices in that time. Justices joined and quit frequently.[26] John Jay declined a second term as Chief Justice, complaining that the Court lacked “energy, weight and dignity.”[27]

The Supreme Court’s use of judicial review power was established in the case of Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. 137 (1803).For the first time, the Supreme Court declared a Congressional law unconstitutional, clarifying the roles of, and the checks and balances among, the three branches of the federal government (Executive, Legislative, and Judicial). Recall from Chapter 1, Black’s Law dictionary defines checks and balances as “The theory of governmental power and functions whereby each branch of government has the ability to counter the actions of any other branch, so that no single branch can control the entire government.”[28] The Supreme Court in Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee (1813) established its power to decide if a state court had properly interpreted the federal Constitution.[29] The Court cited the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution, in Article VI, Clause 2, which makes the United States sovereign and the final arbiter of all cases that arise under the Constitution. Therefore, where a conflict exists between federal law and a state constitution or statute, the federal law and the Supreme Court of the United States’ interpretation of said law will prevail.[30]

So the question became, what standards or criteria would a particular court apply to exercise its judicial review power of a statute or regulation, in the court’s effort to ensure conformity with Constitutional principles? To answer this question, the authors turn your attention to an important concept to consider throughout your time of engaging with this text. Although the Constitution was written many years and centuries ago, the Supreme Court of the United States is tasked with applying and interpreting the Constitution to deal with today’s issues. The Constitution is a living, breathing document which has relevance and importance to yesteryear, today, and forevermore. However, the Framers could not and did not consider some of the following topics when drafting the Constitution:

- DNA testing

- Government Surveillance

- Global positioning satellite (GPS) tracking

- Online privacy

- Social media

- Brain scans to predict behavior

- Cybercurrency

- Biometrics for facial recognition”[31]

- Assault weapons, designed for military use and quick efficient killing

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) or

- Equal treatment and power of the three branches (Legislative, Executive, and Judicial)

Thus the Supreme Court of the United States has relied upon many methods to interpret how the Constitution views the above areas as well as any additional challenges which may arise. In 2018, the Congressional Research Service examined eight of the most common methods of interpreting the Constitution. The Modes of Constitutional interpretation are:

- Textualism

- Original meaning

- Judicial precedent

- Pragmatism

- Moral reasoning

- National identity (ethos)

- Structuralism and

- Historical practices[32]

The eight modes are not exhaustive, but provide “ways of figuring out a particular meaning of a provision within the Constitution.”[33] Thus, prior to delving into the constitutional debates, taking sides, or digging one’s heels into a particular position, it is worth identifying why you may identify with a particular meaning. This provides context and space to allow you and those who you engage with around the constitution to explore, discuss, debate, and consider other interpretations of the same portions of the Constitution. Therefore, below we will take a deep dive into each of these methods of interpretation.

1. “Textualism – Textualism is a mode of interpretation that focuses on the plain meaning of the text of a legal document. Textualism usually emphasizes how the terms in the Constitution would be understood by people at the time they were ratified, as well as the context in which those terms appear. Textualists usually believe there is an objective meaning of the text, and they do not typically inquire into questions regarding the intent of the drafters, adopters, or ratifiers of the Constitution and its amendments when deriving meaning from the text.”[34] Typically, this is the first method of interpretation, when available.[35]

2. “Original meaning – Whereas textualist approaches to Constitutional interpretation focus solely on the text of the document, originalist approaches consider the meaning of the Constitution as understood by at least some segment of the populace at the time of the Founding. Originalists generally agree that the Constitution’s text had an “objectively identifiable” or public meaning at the time of the Founding that has not changed over time, and the task of judges and Justices (and other responsible interpreters) is to construct this original meaning.”[36] In short, “what was the identifiable meaning of the text at the time it was written?”[37]

3. “Judicial precedent – The most commonly cited source of Constitutional meaning is the Supreme Court’s prior decisions on questions of Constitutional law. For most, if not all Justices, judicial precedent provides possible principles, rules, or standards to govern judicial decisions in future cases with arguably similar facts.”[38] This is also known as stare decisis. Remember to read this section later in the text.

4. “Pragmatism – Pragmatist approaches often involve the Court weighing or balancing the probable practical consequences of one interpretation of the Constitution against other interpretations. One flavor of pragmatism weighs the future costs and benefits of an interpretation to society or the political branches, selecting the interpretation that may lead to the perceived best outcome. Under another type of pragmatist approach, a court might consider the extent to which the judiciary could play a constructive role in deciding a question of Constitutional law.”[39] This method of interpretation considers the costs of the Supreme Court’s interpretation. An example might be whether police officers should be allowed the freedom to search anyone for any reason.[40]

5. “Moral reasoning – This approach argues that certain moral concepts or ideals underlie some terms in the text of the Constitution (e.g., “equal protection” or “due process of law”), and that these concepts should inform judges’ interpretations of the Constitution.”[41]

6. “National identity (ethos) – Judicial reasoning occasionally relies on the concept of a “national ethos,” which draws upon the distinct character and values of the American national identity and the nation’s institutions in order to elaborate on the Constitution’s meaning.”[42] This method of interpretation seems quite subject as it is inherent that one must first determine what the “distinct character and values” are before addressing its impact on cases. Additionally, not everyone agrees upon these same “distinct character and values” within the United States.

7. “Structuralism – Another mode of constitutional interpretation draws inferences from the design of the Constitution: the relationships among the three branches of the federal government (commonly called separation of powers); the relationship between the federal and state governments (known as federalism); and the relationship between the government and the people.”[43]

8. “Historical practices – Prior decisions of the political branches, particularly their long-established, historical practices, are an important source of Constitutional meaning. Courts have viewed historical practices as a source of the Constitution’s meaning in cases involving questions about the separation of powers, federalism, and individual rights, particularly when the text provides no clear answer.”[44]

Once you have sufficiently identified the basic methods and modes of interpretation, it is the authors’ hope that you will take your time and a blank approach to learning the Constitution, then carefully identifying which mode or modes of interpretation are at play in the opinion.

ANALYSIS OF ARTICLE III

Section 3

Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying War against them, or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort. No Person shall be convicted of Treason unless on the Testimony of two Witnesses to the same overt Act, or on Confession in open Court.

The Congress shall have Power to declare the Punishment of Treason, but no Attainder of Treason shall work Corruption of Blood, or Forfeiture except during the Life of the Person attainted.

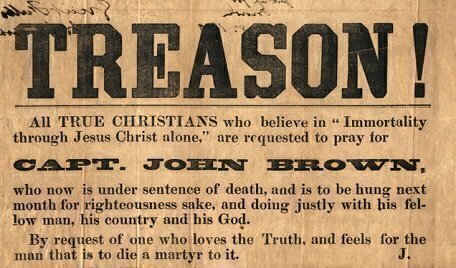

Example of Treason – Capt. John Brown

“On 16 October 1859 John Brown led eighteen men-thirteen whites and five blacks-into Harpers Ferry, Virginia. Three other members of his force formed a rearguard at a nearby Maryland farm. A veteran of the violent struggles between pro- and antislavery forces in Kansas, Brown intended to provoke a general uprising of African Americans that would lead to a war against slavery. The raiders seized the federal buildings and cut the telegraph wires. Expecting local slaves to join them, Brown and his men waited in the armory while the townspeople surrounded the building. The raiders and the civilians exchanged gunfire, and eight of Brown’s men were killed or captured. By daybreak on 18 October, U.S. Marines under the command of Brevet Colonel Robert E. Lee stormed Brown’s position in the arsenal’s enginehouse and captured or killed most of his force. Five of the conspirators, including Brown’s son Owen, escaped to safety in Canada and the North. Severely wounded and taken to the jail in Charles Town, Virginia, John Brown stood trial for treason against the commonwealth of Virginia, for murder, and for conspiring with slaves to rebel. On 2 November a jury convicted him and sentenced him to death. Brown readily accepted the sentence and declared that he had acted in accordance with God’s commandments. Responding to persistent rumors and written threats, Henry A. Wise, governor of Virginia, called out state militia companies to guard against a possible rescue of Brown and his followers. On 2 December 1859, Brown was hanged in Charles Town.”[45]

“Treason is a unique offense in our Constitutional order – the only crime expressly defined by the Constitution which applies to Americans who have betrayed the allegiance they are presumed to owe to the United States. While the Constitution’s framers shared the centuries-old view that all citizens owed a duty of loyalty to their home nation, they included the Treason Clause not so much to underscore the seriousness of such a betrayal, but to guard against the historic use of treason prosecutions by repressive governments to silence otherwise legitimate political opposition. Debate surrounding the clause at the Constitutional Convention thus focused on ways to narrowly define the offense and to protect against false or flimsy prosecutions.”[46]

The Constitution specifically identifies what constitutes treason against the United States and, importantly, limits the offense of treason to only two types of conduct: (1) “levying war” against the United States; or (2) “adhering to [the] enemies [of the United States], giving them aid and comfort.”[47] There have not been many treason prosecutions in American history – indeed, only one person has been indicted for treason against the United States – Adam G.[48] Gadahn was charged for treason as a result of his involvement with al-Qaeda propaganda videos in 2006.[49] Unfortunately, Gadahn would never faces charges for his crime as he was killed by a Pakistian air strike instead. Treason may continue to prove a difficult case to charge because of its specificity.

Article IV – States, Citizenship, New States

*Highlighted sections indicate changes identified in other parts of the Constitution of the United States. Signed in convention September 17, 1787. Ratified June 21, 1788. A portion of Article IV, Section 2, was changed by the 13th Amendment.

Section 1

Full Faith and Credit shall be given in each State to the public Acts, Records, and judicial Proceedings of every other State. And the Congress may by general Laws prescribe the Manner in which such Acts, Records and Proceedings shall be proved, and the Effect thereof.

Section 2

The Citizens of each State shall be entitled to all Privileges and Immunities of Citizens in the several States.

A Person charged in any State with Treason, Felony, or other Crime, who shall flee from Justice, and be found in another State, shall on Demand of the executive Authority of the State from which he fled, be delivered up, to be removed to the State having Jurisdiction of the Crime.

No Person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due.

Section 3

New States may be admitted by the Congress into this Union; but no new State shall be formed or erected within the Jurisdiction of any other State; nor any State be formed by the Junction of two or more States, or Parts of States, without the Consent of the Legislatures of the States concerned as well as of the Congress.

The Congress shall have Power to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property belonging to the United States; and nothing in this Constitution shall be so construed as to Prejudice any Claims of the United States, or of any particular State.

Section 4

The United States shall guarantee to every State in this Union a Republican Form of Government, and shall protect each of them against Invasion; and on Application of the Legislature, or of the Executive (when the Legislature cannot be convened) against domestic Violence.

INTRODUCTION TO ARTICLE IV

Article IV of the United States Constitution serves a significant purpose. In short, it sets forth the expected relationship between states as it relates to laws. “It contains several provisions concerning the federalist structure of government established by the Constitution, which divides sovereignty between the states and the National Government.”[50] Article IV further reminds states of the urgency of respect for other states’ laws and orders, especially when states have codified different laws about a particular topic. In this way, Congress limited federal authority, while maintaining the sovereignty of state laws.

ANALYSIS OF ARTICLE IV

Section 1

Full Faith and Credit shall be given in each State to the public Acts, Records, and judicial Proceedings of every other State. And the Congress may by general Laws prescribe the Manner in which such Acts, Records and Proceedings shall be proved, and the Effect thereof.

Full Faith and Credit Clause[51]

Most of the original Constitution focuses on creating the federal government, defining its relationship to the states and the people at large. Article IV addresses something different: the states’ relations with each other, sometimes called “horizontal federalism.” Its first section, the Full Faith and Credit Clause, requires every state, as part of a single nation, to give a certain measure of respect to every other state’s laws and institutions. Black’s Law Dictionary defines Full Faith and Credit Clause as the clause in the “[United States Constitution, Article} IV, § 1, which requires states to give effect to the acts, public records, and judicial decisions of other states.”[52]

The first part of the Clause, largely borrowed from the Articles of Confederation, requires each state to pay attention to the other states’ statutes, public records, and court decisions. The second sentence lets Congress decide how those materials can be proved in court and what effect they will have. The current implementing statute, 28 U.S.C. §1738, declares that these materials should receive “the same full faith and credit” in each state as offered in the state “from which they are taken.”

*In recent years, the most controversial applications of the Full Faith and Credit Clause have involved family law. Each state has slightly different laws about marriage, and marriages themselves typically are not treated as judgments receiving nationwide effect. Until recently, same-sex marriages formed in one state were not always recognized elsewhere. Congress attempted to use its power under the clause to slow the recognition of same-sex marriages by passing the Defense of Marriage Act (signed into law by former President Bill Clinton), but this was rendered obsolete by the Supreme Court’s decision in Obergefell v. Hodges (2015).[53] The Defense of Marriage Act was partially overruled in 2012. The remainder of the Defense of Marriage Act was overruled in Obergefell. Additionally, another case overruled the federal protection of abortion in the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022) decision. After the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022) decision (which held that there is no Constitutional right to an abortion), Associate Justice Thomas indicated his desire to revisit many other landmark cases including Obergefell v. Hodges.[54] As a result, Congress responded with a law that will address same-sex and interracial marriages. The Respect for Marriage Act was introduced in response to Justice Thomas’ comments in the Dobbs case. However, this area remains ambiguous as supporters and opponents struggle to determine if the Supreme Court of the United States will reverse itself in Obergefell.[55]

ANALYSIS OF ARTICLE IV

Section 2

The Citizens of each State shall be entitled to all Privileges and Immunities of Citizens in the several States.

A Person charged in any State with Treason, Felony, or other Crime, who shall flee from Justice, and be found in another State, shall on Demand of the executive Authority of the State from which he fled, be delivered up, to be removed to the State having Jurisdiction of the Crime.

No Person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due.

Article IV, §2 Examples of Privileges and Immunities[56]

Article IV, §2 sets forth three Clauses, each of which concerns the movement of persons throughout the Union.

The first of these, the Privileges and Immunities Clause, stipulates that the citizens of each state shall enjoy the “privileges and immunities of citizens” in the other states. Black’s Law Dictionary defines Privileges and Immunities Clause as “[t]he constitutional provision {United States Constitutional Article} IV, §2, {Clause} 1 prohibiting a state from favoring its own citizens by discriminating against other states’ citizens who come within its borders.”[57] Conversely, where the interstate traveler is a fugitive from criminal justice, the second provision – the Extradition Clause – requires the person’s forcible rendition to the state where the alleged crime occurred. Finally, the Fugitive Slave Clause (now obsolete) extended this rule of coercive rendition to interstate fugitives from slavery – that is, fugitives from injustice.

Unlike the other clauses of Article IV, the provisions in §2 vest in Congress no express enforcement power or duty. Instead, each uses a passive-voice verb – “shall be entitled” (in the first clause) and “shall be delivered up” (in the second and third clauses) – without any clear identification of the authority or authorities who are to ensure this entitlement or this rendition. The provisions mention only the persons entitled to the benefit: the citizen, under the Privileges and Immunities Clause. Additionally, the executive of the state of the alleged crime as noted under the Extradition Clause with the slaveholder under the Fugitive Slave Clause.

The adoption of the Privileges and Immunities Clause addressed a key problem inherent in the new federal system. On July 4, 1776, the representatives of “one People” had declared that the thirteen “United Colonies” were “free and independent states.” From the beginning, the United States was marked by a tension between unity and multiplicity: one united people, but thirteen independent states. And from the beginning, this tension posed many challenges, including the threat that the several states’ independence would turn former fellow British subjects into citizens of thirteen separate republics—mutual aliens, rather than one people.

As for the Fugitive Slave Clause, at the end of the day, since the word “slavery” was never mentioned in the Constitution, northerners could argue that the Constitution did not recognize the legality of slavery. However, southerners such as General Cotesworth Pinckney argued, “[w]e have obtained a right to recover our slaves in whatever part of America they may take refuge, which is a right we had not before.”[58] Ultimately, the issue of slavery’s constitutional status was far from settled.

ANALYSIS OF ARTICLE IV

Section 3

New States may be admitted by the Congress into this Union; but no new State shall be formed or erected within the Jurisdiction of any other State; nor any State be formed by the Junction of two or more States, or Parts of States, without the Consent of the Legislatures of the States concerned as well as of the Congress.

The Congress shall have Power to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property belonging to the United States; and nothing in this Constitution shall be so construed as to Prejudice any Claims of the United States, or of any particular State.

This Clause affords Congress the power to admit new states. Most of the discussion at the Constitutional Convention focused on the latter, limiting, portion of the clause—providing that new states can be carved out of or formed from existing states only with the consent of those existing states. Several convention delegates objected to this provision on the grounds that, because several of the existing large states laid claims to vast swathes of western territories and other lands, those states would never consent to form new states in those territories. Thus, the large states would only become larger and more powerful over time. But the prevailing sentiment at the Convention was that a political society cannot be split apart against its will.

While the consent requirement garnered the most discussion at the framing, it has come into play only a handful of times in American history. One such time was when Massachusetts consented to the formation of Maine. Most intriguingly, Virginia was treated as consenting to the formation of West Virginia at the outset of the Civil War. Although it was actually a breakaway, pro-Union province of Virginia that declared itself to be the lawful government of Virginia, then purported to give “Virginia’s” consent to the creation of the new state of West Virginia – which was to occupy that same breakaway corner of Virginia.[59]

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

The opening portion of the Clause—granting Congress the general power to admit new states—has played a far more significant role in American history. Only thirteen states ratified the Constitution pursuant to Article VII. All of the remaining thirty-seven states were subsequently admitted to the Union by Congress pursuant to this power.[60]

ANALYSIS OF ARTICLE IV

Section 4

The United States shall guarantee to every State in this Union a Republican Form of Government, and shall protect each of them against Invasion; and on Application of the Legislature, or of the Executive (when the Legislature cannot be convened) against domestic Violence.

The Guarantee Clause requires the United States to guarantee to the states a republican form of government and provide protection from foreign invasion and domestic violence. Although rarely formally invoked by Congress, the President, or the courts, there is some consensus on what it means.

At its core, the Guarantee Clause provides for majority rule. A republican government is one in which the people govern through elections. This is the constant refrain of the Federalist Papers. Alexander Hamilton, for example, noted in The Federalist No. 57: “The elective mode of obtaining rulers is the characteristic policy of republican government.”[61]

Thus, the Guarantee Clause imposes limitations on the type of government a state may have. The Clause requires the United States to prevent any state from imposing rule by monarchy, dictatorship, aristocracy, or permanent military rule, even through majority vote. Instead, governing by electoral processes is constitutionally required.

However, the Guarantee Clause does not speak to the details of the republican government that the United States is to guarantee. For example, it is difficult to imagine that those who enacted the Constitution believed the Guarantee Clause would be concerned with state denial of the right to vote on the basis of race, sex, age, wealth, or property ownership. Article I, §2 of the Constitution left voting qualifications in the hands of the states, although state authority in this area has been altered by subsequent amendments. The Guarantee Clause also does not require any particular form of republican governmental structure.[62]

Article V - Amendment Process

Signed in convention September 17, 1787. Ratified June 21, 1788

The Congress, whenever two thirds of both Houses shall deem it necessary, shall propose Amendments to this Constitution, or, on the Application of the Legislatures of two thirds of the several States, shall call a Convention for proposing Amendments, which, in either Case, shall be valid to all Intents and Purposes, as Part of this Constitution, when ratified by the Legislatures of three fourths of the several States, or by Conventions in three fourths thereof, as the one or the other Mode of Ratification may be proposed by the Congress; Provided that no Amendment which may be made prior to the Year One thousand eight hundred and eight shall in any Manner affect the first and fourth Clauses in the Ninth Section of the first Article; and that no State, without its Consent, shall be deprived of its equal Suffrage in the Senate.

America's Amoral Article V?[63]

INTRODUCTION TO ARTICLE V

The Constitution of the United States is the "...oldest written national constitution in operation, completed in 1787 at the Constitutional Convention of 55 delegates who met in Philadelphia, ostensibly to amend the Articles of Confederation."[64] Although the original Constitution (the Preamble and the Articles) was ratified in 1788, recall from Chapter 1, the first discussion of amendments occurred in 1787 during the Constitutional Convention.[65] In September 1789, Congress proposed the first 12 amendments which would later become the Bill of Rights, in its modified form of 10 amendments.[66] Formally, there has been more than 11,000 proposed amendments, but formally the Constitution has been amended 27 times.[67]

Article V of the United States Constitution provides for change via a Constitutional convention to propose amendments, regardless of Congress's approval.[68] Those proposed amendments would then be sent to the states for ratification. Although rarely used, there are technically four methods of amending the Constitution of the United States. A close reading of the Constitution and substitute changes will help to explain each method. By way of introduction, the Constitution can be amended by two methods via Article V; however, two additional methods are identified below as a result of the changes identified:

- Two-thirds Congressional proposal with Three-fourths ratification by state legislatures. (most amendments for this method)

- Conventional proposal of states with ratification by state conventions. (never used)

- Conventional proposal of states with ratification by state legislatures. (never used)

- Congressional proposal with ratification by state conventions. (repeal of 18th Amendment by 21st Amendment)[69]

ANALYSIS OF ARTICLE V

Article V of the Constitution says how the Constitution can be amended—that is, how provisions can be added to the text of the Constitution. The Constitution is not easy to amend: only twenty-seven amendments have been added to the Constitution since it was adopted.

Article V spells out a few different ways in which the Constitution can be amended. One method—the one used for every amendment so far—is that Congress proposes an amendment to the states; the states must then decide whether to ratify the amendment. But in order for Congress to propose an amendment, two-thirds of each House of Congress must vote for it. And then three-quarters of the states must ratify the amendment before it is added to the Constitution. So if slightly more than one-third of the House of Representatives, or slightly more than one-third of the Senate, or thirteen out of the fifty states object to a proposal, it will not become an amendment by this route. In that way, a small minority of the country has the ability to prevent an amendment from being added to the Constitution.

The amendments to the Constitution have come in waves. The first twelve Amendments, including the Bill of Rights, were added by 1804. Afterwards, there were no amendments for more than half a century. In the wake of the Civil War, three important Amendments were added: the Thirteenth (outlawing slavery) in 1865, the Fourteenth (mainly protecting equal civil rights) in 1868, and the Fifteenth (forbidding racial discrimination in voting) in 1870.

After the Civil War Amendments, another forty-three years passed until the Constitution was amended again; then four more Amendments (Sixteen through Nineteen) were added between 1913 and 1920. Seven more amendments were adopted at pretty regular intervals between 1920 and 1971. With the exception of one very unusual amendment (the 27th Amendment), there have been no amendments to the Constitution since 1971. The 27th Amendment was ratified in 1992, after first being proposed over two hundred years earlier.[70]

Article VI - Debts, Supremacy, Oaths, Religious Tests

Signed in convention September 17, 1787. Ratified June 21, 1788

All Debts contracted and Engagements entered into, before the Adoption of this Constitution, shall be as valid against the United States under this Constitution, as under the Confederation.

This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.

The Senators and Representatives before mentioned, and the Members of the several State Legislatures, and all executive and judicial Officers, both of the United States and of the several States, shall be bound by Oath or Affirmation, to support this Constitution; but no religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States.

Religious Tests[71]

INTRODUCTION TO ARTICLE VI

Article VI paves the way to establish the Constitution as the premier document for supreme authority in the United States. Additionally, Article VI has binding authority upon all state judges, barring states' law and constitution. Moreover, "...the U.S. government...remained bound by the obligations of the predecessor governments established under the Articles of Confederation and Continental Congresses."[72] All federal and state officials are required to make the United States Constitution their first loyalty regardless of their level of government. Finally, Article VI sought to protect public officials' religious privacy as this may not be required in order to hold office.[73]

ANALYSIS OF ARTICLE VI

Instead of giving Congress additional powers, the Supremacy Clause simply addresses the legal status of the laws that other parts of the Constitution empower Congress to make, as well as the legal status of treaties and the Constitution itself. The core message of the Supremacy Clause is simple: the Constitution and federal laws (of the types listed in the first part of the Clause) take priority over any conflicting rules of state law. This principle is so familiar that we often take it for granted. Still, the Supremacy Clause has several notable features. To begin, the Supremacy Clause contains the Constitution’s most explicit references to what lawyers call “judicial review” which is the idea that even duly enacted statutes do not supply rules of decision for courts to the extent that the statutes are unconstitutional. Legal scholars insist that the Supremacy Clause’s reference to “the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance [of the Constitution]” itself incorporates this idea; in their view, a federal statute is not “made in Pursuance [of the Constitution]” unless the Constitution really authorizes Congress to make it. Other scholars say that this phrase simply refers to the lawmaking process described in Article I, and does not necessarily distinguish duly enacted federal statutes that conform to the Constitution from duly enacted federal statutes that do not. But no matter how one parses this specific phrase, the Supremacy Clause unquestionably describes the Constitution as “Law” of the sort that courts apply. This point is a pillar of the argument for judicial review. In addition, the Supremacy Clause explicitly specifies that the Constitution binds the judges in every state notwithstanding any state laws to the contrary.

Under the Supremacy Clause, the “supreme Law of the Land” also includes federal statutes enacted by Congress. Within the limits of the powers that Congress gets from other parts of the Constitution, Congress can establish rules of decision that American courts are bound to apply, even if state law purports to supply contrary rules. Also, Congress has some authority to wholly limit state law or otherwise to restrict how state law interacts with topics. While the directives that Congress enacts are indeed authorized by the Constitution, the United States' congressional authority takes priority over both the ordinary laws and the constitution of each individual state.[74] During the ratification period, Anti-Federalists objected to the fact that federal statutes and treaties could override aspects of each state’s constitution and bill of rights. While this feature of the Supremacy Clause was controversial, it was also unambiguous.[75]

After requiring all federal and state legislators and officers to swear or affirm to support the federal Constitution, Article VI specifies that “no religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States.” The prohibitive No Religious Test Clause banned a longstanding form of religious discrimination practiced both in England and the United States. The No Religious Test Clause of the Constitution provided a limited, but enduring textual commitment to religious liberty. Further, the clause promoted equality that has influenced the way Americans have understood the relationship between government and religion for the last two centuries. Justice Black reiterated this test in Torcaso v. Watkins (1961) as he emphasized

“[w]e repeat and again reaffirm that neither a State nor the Federal Government can constitutionally force a person 'to profess a belief or disbelief in any religion.' Neither can constitutionally pass laws or impose requirements which aid all religions as against nonbelievers, and neither can aid those religions based on a belief in the existence of God as against those religions founded on different beliefs.”[76]

At the time the United States Constitution was adopted, religious qualifications for holding office also were pervasive throughout the states. Delaware’s constitution, for example, required government officials to “profess faith in God the Father, and in Jesus Christ His only Son, and in the Holy Ghost."[77] North Carolina barred anyone “who shall deny the being of God or the truth of the Protestant religion” from serving in the government.[78] Unlike the rule in England, however, American religious tests did not limit office-holding to members of a particular established church. Every state allowed Protestants of all varieties to serve in government. Furthermore, religious tests were designed to exclude certain people, often Catholics or non-Christians, from holding office based on their faith.[79]

As is true of virtually all Constitutional provisions, the No Religious Test Clause in Article VI only restricts governmental action. Private citizens do not violate the Constitution if they vote against a political candidate because of his or her religion. A harder question, which has provoked considerable contemporary debate, is whether the Clause extends beyond a ban against oaths and prohibits government officials from taking the religious views of an individual into account in selecting or confirming that individual for a federal position—such as an appointment to the Supreme Court.[80]

Article VII - Ratification

Signed in convention September 17, 1787. Ratified June 21, 1788

The Ratification of the Conventions of nine States, shall be sufficient for the Establishment of this Constitution between the States so ratifying the Same.

Signers

Done in Convention by the Unanimous Consent of the States present the Seventeenth Day of September in the Year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and Eighty seven and of the Independence of the United States of America the Twelfth. In witness whereof We have here unto subscribed our Names,

George Washington, President and deputy from Virginia

New Hampshire

John Langdon

Nicholas Gilman

Massachusetts

Nathaniel Gorman

Rufus King

Connecticut

William Samuel Johnson

Roger Sherman

New York

Alexander Hamilton

New Jersey

William Livingston

David Brearley

William Paterson

Jonathan Dayton

Pennsylvania

Benjamin Franklin

Thomas Mifflin

Robert Morris

George Clymer

Thomas Fitzsimons

Jared Ingersoll

James Wilson

Gouverneur Morris

Delaware

George Read

Gunning Bedford Jr.

John Dickinson

Richard Bassett

Jacob Broom

Maryland

James McHenry

Daniel of St. Thomas Jenifer

Daniel Carroll

Virginia

John Blair

James Madison Jr.

North Carolina

William Blount

Richard Dobbs Spaight

Hugh Williamson

South Carolina

John Rutledge

Charles Cotesworth Pinckney

Charles Pinckney

Pierce Butler

Georgia

William Few

Abraham Baldwin

Attest: William Jackson, Secretary

INTRODUCTION TO ARTICLE VII

"The controversies over Article VII that occurred during the ratification process were over the substance of the mandated ratification process, not over what the text actually mandated. Anti-Federalists and Federalists agreed on the meaning of “Ratification,” “nine” and “States.” The main dispute between Anti-Federalists and Federalists was whether the new Constitution could lawfully be ratified by nine states."[81]

According to the text of Article VII, once the conventions of nine states ratified the Constitution, then the document was valid. Thus, when New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify on June 21, 1788, the Constitution became valid. This is further evidenced in Owings v. Speed (1820)[82] which follows:

"The Conventions of nine States having adopted the Constitution, Congress, in September or October, 1788, passed a resolution in conformity with the opinions expressed by the Convention, and appointed the first Wednesday in March of the ensuing year as the day, and the then seat of Congress as the place, ‘for commencing proceedings under the Constitution.'

...The New Government did not commence until the old Government expired. It is apparent that the government did not commence on the Constitution being ratified by the ninth State; for these ratifications were to be reported to Congress, whose continuing existence was recognized by the Convention, and who were requested to continue to exercise their powers for the purpose of bringing the new Government into operation. In fact, Congress did continue to act as a Government until it dissolved on the 1st of November, by the successive disappearance of its Members. It existed potentially until the 2d of March, the day proceeding that on which the Members of the new Congress were directed to assemble.

The resolution of the Convention might originally have suggested a doubt, whether the government could be in operation for every purpose before the choice of a President; but this doubt has been long solved, and were it otherwise, its discussion would be useless, since it is apparent that its operation did not commence before the first Wednesday in March 1789 . . . ."[83]

ANALYSIS OF ARTICLE VII

Article VII came to be viewed as having important implications for federalism and secession. Chief Justice John Marshall in McCullough v. Maryland (1819) argued that Article VII’s requirement that the Constitution be ratified by the people in convention showed that it was not a compact between the states, but an emanation of the people as a whole.[84] According to Marshall, the conventions occurred at the state level, because of mere historical practice and convenience.[85]

By contrast, the Confederate States interpreted Article VII differently. They viewed each state’s ratification as a decision by that state, acting through its sovereign people.[86] When these states attempted to secede, they often did so by having a convention adopt a provision repealing their prior ratification of the Constitution under Article VII.[87] Thus, these states viewed the Article VII ratification as an act of the people of the state that could be repealed.

Critical Reflections:

- Do you think the Framers properly balanced the powers given to states vs. those given to the federal courts (government)? Why or why not?

- Over the last half-century the installation of new U.S. Supreme Court justices has been mostly a partisan decision. Given that their appointment is for life, would you install a process to rebalance the Court so that it is more representative of both major political parties? Would this solve the problem over the next 50 years? Why or why not?

- Does a requirement that members of Congress swear allegiance to the Constitution on a Bible violate the clause prohibiting religious tests?

- Three Presidents have been impeached (one twice) by the U.S. House of Representatives, but none have been convicted and removed from office by the Senate. Should the Constitution be amended to allow for a majority vote to convict the President in the Senate? Why or why not?

- Fryling, T. M. F. (2023). Constitutional law in criminal justice. Aspen Publishing, p. 7. ↵

- Fryling, 2023. ↵

- Gamble v. United States, 139 S. Ct. 1960 (2019). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- STATUTE, Black's Law Dictionary (11th ed. 2019). ↵

- JURISDICTION, Black's Law Dictionary (11th ed. 2019). ↵

- De Tocqueville, A., Grant, S. D., & Kessler, S. (2001). Democracy in America (Abridged). Hackett Publishing, p. 122. ↵

- Justices(n.d.)https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/images/2022_Roberts_Court_Formal_083122_Web.jpg ↵

- History and traditions. (n.d.). https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/historyandtraditions.aspx ↵

- Garnett, R., & Strauss, D. (n.d.). Interpretation: Article III, Section One | The National Constitution Center. Interactive Constitution. Retrieved May 31, 2021, from https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/interpretation/article-iii/clauses/45 ↵

- United States Courts. (n.d.). Court website links. Retrieved May 31, 2021, from https://www.uscourts.gov/about-federal-courts/federal-courts-public/court-website-links ↵

- Resnik, J., & Walsh, K. (n.d.). Interpretation: Article III, Section Two | The National Constitution Center. Interactive Constitution. Retrieved May 31, 2021, from https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/interpretation/article-iii/section/203 ↵

- Elving, R. (2018, June 29). What Happened with Merrick Garland in 2016 and Why it Matters Now. NPR. https://choice.npr.org/index.html?origin=https://www.npr.org/2018/06/29/624467256/what-happened-with-merrick-garland-in-2016-and-why-it-matters-now ↵

- Takeaways from attorney general merrick garland’s senate judiciary committee hearing. (2023, March 1). CNN Politics. Retrieved July 19, 2023, from https://www.cnn.com/2023/03/01/politics/merrick-garland-senate-judiciary-committee-testimony/index.html ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Interpretation: Article III, Section 2 By Judith Resnik and Kevin C. Walsh | Constitution Center. (n.d.). National Constitution Center – constitutioncenter.org. https://constitutioncenter.org/the-constitution/articles/article-iii/section/203#:~:text=Article%20III%2C%20Section%202%20creates,the%20parties%20come%20from%20different ↵

- Garnett, R., & Strauss, D. (n.d.). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Printz v. United States, 521 U.S. 898 (1997). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Rivkin, D. B., Jr, & Taranto, J. (2023, July 28). Samuel Alito, the Supreme Court’s Plain-Spoken defender. WSJ. https://www.wsj.com/articles/samuel-alito-the-supreme-courts-plain-spoken-defender-precedent-ethics-originalism-5e3e9a7 ↵

- Barnes, R. (2023, July 28). Alito says Congress has no authority to police Supreme Court ethics. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2023/07/28/alito-ethics-supreme-court-congress/ ↵

- U.S. Federal Courts 101 | Constitutional Accountability Center. (2018, February 25). Constitutional Accountability Center. https://www.theusconstitution.org/u-s-federal-courts-101/ ↵

- Elkins & McKitrick, 1993, p. 62-64 ↵

- Waldman, M. (2023). The supermajority: How the Supreme Court Divided America. Simon and Schuster. ↵

- University of Virginia Press. (n.d.). Founders Online: To John Adams from John Jay, 2 January 1801. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-4745 ↵

- CHECKS AND BALANCES, Black's Law Dictionary (11th ed. 2019). ↵

- Martin's v. Hunter's Lessee, 14 U.S. 304 (1816). ↵

- Fryling, T. M. F. (2023). Constitutional law in criminal justice. Aspen Publishing. ↵

- Fryling, T. M. F. (2023). Constitutional law in criminal justice. Aspen Publishing. ↵

- Murrill, B.J. (2018). Modes of Constitutional interpretation: A CRS report prepared for members of Congress. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Fryling, 2023. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Fryling, 2023. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Fryling, 2023. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- John Brown’s Raid. (n.d.). https://www.lva.virginia.gov/exhibits/deathliberty/johnbrown/index.htm ↵

- Interpretation: Treason Clause | Constitution Center. (n.d.). National Constitution Center – constitutioncenter.org. https://constitutioncenter.org/the-constitution/articles/article-iii/clauses/39 ↵

- Crane, P., & Pearlstein, D. (n.d.). Interpretation: Treason Clause | The National Constitution Center. Interactive Constitution. Retrieved May 31, 2021, from https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/interpretation/article-iii/clauses/39 ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Overview of Article IV, Relationships between the states. (n.d.). LII / Legal Information Institute. https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution-conan/article-4/overview-of-article-iv-relationships-between-the-states ↵

- Milner, J. (2018). Blog - AP US government and politics. GoPoPro. https://www.gopopro.com/vocab/2017/3/8/full-faith-and-credit-clause ↵

- FULL FAITH AND CREDIT CLAUSE, Black's Law Dictionary (11th ed. 2019). ↵

- Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. 644 (2015); Sachs, S., & Saunders, S. (n.d.). Interpretation: Article IV, Section 1: Full Faith and Credit Clause | The National Constitution center. Interactive Constitution. Retrieved May 31, 2021, from https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/interpretation/article-iv/clauses/44 ↵

- Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, No. 19-1392, 597 U.S. ___ (2022). ↵

- Three minute legal talks: The Respect for Marriage Act | UW School of Law. (2022, December 13). UW School of Law. https://www.law.uw.edu/news-events/news/2022/respect-for-marriage-act ↵

- Treason, J. M. B. F. I. ‘. W. J. C. (n.d.). Article IV of the U.S. https://slideplayer.com/slide/6417335/ ↵

- PRIVILEGES AND IMMUNITIES CLAUSE, Black's Law Dictionary (11th ed. 2019). ↵

- Gross, A., & Upham, D. (n.d.). Interpretation: Article IV, Section 2: Movement of Persons Throughout the Union | The National Constitution Center. Interactive Constitution. Retrieved May 31, 2021, from https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/interpretation/article-iv/clauses/37 ↵

- Biber, E., & Colby, T. (n.d.). Interpretation: The admissions clause | The National Constitution Center. Interactive Constitution. Retrieved May 31, 2021, from https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/interpretation/article-iv/clauses/46 ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- The avalon project: The federalist papers. (2008). The Federalist Papers : No. 57. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/fed22.asp ↵

- Please review the Appendix and ratification dates for each portion of the United States Constitution.[footnote]Chin, G., & Hawley, E. (n.d.). The guarantee clause. National Constitution Center. Retrieved November 19, 2020, from https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/interpretation/article-iv/clauses/42 ↵

- Guerra-Pujol, V. a. P. B. F. E. (2020, September 24). America’s amoral Article V? Prior Probability. https://priorprobability.com/2020/09/17/americas-amoral-article-v/ ↵

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (n.d.). Constitution of the United States summary. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/summary/Constitution-of-the-United-States-of-America ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- U.S. Senate: Amending the Constitution. (2019, September 23). https://www.senate.gov/reference/reference_index_subjects/Constitution_vrd.htm#:~:text=It%20has%20become%20the%20landmark,11%2C000%20amendments%20proposed%20since%201789. ↵

- Government Publishing Office. (n.d.). Proposed amendments not ratified by the states. Gov Info. Retrieved July 19, 2023, from https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CONAN-1992/pdf/GPO-CONAN-1992-8.pdf ↵

- U.S. Senate: Amending the Constitution. (2019, September 23). https://www.senate.gov/reference/reference_index_subjects/Constitution_vrd.htm#:~:text=It%20has%20become%20the%20landmark,11%2C000%20amendments%20proposed%20since%201789. ↵

- For a more detailed discussion regarding the Twenty-seventh Amendment and the 200-year journey to ratification in Chapter 14. ↵

- Seering, L. (n.d.). Supreme Court Affirms No Religious Test for Public Office - Freedom From Religion Foundation. https://ffrf.org/ftod-cr/item/14443-supreme-court-affirms-no-religious-test-for-public-office ↵

- Overview of Article IV, Relationships between the states. (n.d.). LII / Legal Information Institute. https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution-conan/article-4/overview-of-article-iv-relationships-between-the-states ↵

- Overview of Article VI, Supreme Law. (n.d.). LII / Legal Information Institute. https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution-conan/article-6/overview-of-article-vi-supreme-law ↵

- Nelson, C., & Roosevelt, K. (n.d.). Interpretation: The supremacy clause | The National Constitution Center. Interactive Constitution. Retrieved May 31, 2021, from https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/interpretation/article-vi/clauses/31 ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Torcaso v. Watkins, 367 U.S. 488 (1961). ↵

- Brownstein, A., & Campbell, J. (n.d.). Interpretation: The no religious test clause | The National Constitution Center. Interactive Constitution. Retrieved May 31, 2021, from https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/interpretation/article-vi/clauses/32 ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Interpretation: Article VII | Constitution Center. (n.d.). National Constitution Center – constitutioncenter.org. https://constitutioncenter.org/the-constitution/articles/article-vii/interpretations/24#:~:text=The%20text%20of%20Article%20VII,End%20of%20story. ↵

- 18 U.S. (5 Wheat.) 420, 422–23 (1820). ↵

- ArtVII.1 Historical Background on Ratification Clause. (n.d.). Constitutional Annotated. Retrieved August 8, 2023, from https://constitution.congress.gov/browse/essay/artVII-1/ALDE_00000389/ ↵

- McCulloch c. Maryland, 17 U.S. 316 (1819). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Graber, M., & Rappaport, M. (n.d.). Interpretation: Article VII | The National Constitution Center. Interactive Constitution. Retrieved May 31, 2021, from https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/interpretation/article-vii/interps/24 ↵

- Ibid. ↵