Chapter 14 – Amendments XVII, XIX, XXIII, XXVI, and XXVII: Voting, Elections, & Representation

Amendment XVII, Amendment XIX, Amendment XXIII, Amendment XXVI, & Amendment XXVII

Richard J. Forst and Tauya R. Forst

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

14.1 Identify the unfamiliar terms of the Seventeenth Amendment.

14.2 Compare the legislative election of Senators from the election of Senators by popular vote.

14.3 Identify the unfamiliar terms of the Nineteenth Amendment.

14.4 Describe the concerns and obstacles women overcame during the march to ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment.

14.5 Identify the unfamiliar terms of the Twenty-third Amendment.

14.6 Define seat of government and its powers according to the Twenty-third Amendment.

14.7 Identify the unfamiliar terms of the Twenty-sixth Amendment.

14.8 Explain the reasoning for the voting age change per the Twenty-sixth Amendment.

14.9 Identify the unfamiliar terms of the Twenty-seventh Amendment.

14.10 Describe how Congress compensated itself prior to the Twenty-seventh amendment.

KEY TERMS

| Disenfranchisement | Suffrage |

| Minor v. Happersatt | Vacancy Clause |

| Senator | Voting |

| Statehood |

Counting the Electoral Vote – David Dudley Field Objects to the Vote of Florida.[1]

Amendment XVII

Passed by Congress May 13, 1912. Ratified April 8, 1913. The 17th Amendment changed a portion of Article I, Section 3.

The Senate of the United States shall be composed of two Senators from each State, elected by the people thereof, for six years; and each Senator shall have one vote. The electors in each State shall have the qualifications requisite for electors of the most numerous branch of the State legislatures.

When vacancies happen in the representation of any State in the Senate, the executive authority of such State shall issue writs of election to fill such vacancies: Provided, That the legislature of any State may empower the executive thereof to make temporary appointments until the people fill the vacancies by election as the legislature may direct.

This amendment shall not be so construed as to affect the election or term of any Senator chosen before it becomes valid as part of the Constitution.

INTRODUCTION

Previously, the authors discussed the consistent theme within the evolution of the United States Constitution as it continues to balance state and federal governments and how that equilibrium impacts the individual’s rights. The Seventeenth Amendment is parallel to this balance as well. Known for its ability to make a significant change to the original United States Constitution, the Seventeenth Amendment has provided the most notable difference in its impact to the composition and process of the legislature. Prior to 1913 and the ratification of Amendment XVII, Art. I, § 3 empowered state legislatures to select United States Senators. Although the original United States Constitution was ratified in 1788, the selection of United States Senators by direct vote of the State’s electorate did not occur for 125 years. Ultimately, the change which occurred in 1913 was rooted in a much earlier version of the Seventeenth Amendment. In 1826, a plan existed to amend the original constitution to include a process which would address some contentious and corrupt elections held in Indiana and New Jersey.[2] This corruption included powerful political machines and pecuniary interests which worked to underline the integrity of the senatorial races. Interestingly, Congress passed a law in 1826 which directed the process and time of the senatorial choices, but refused to change the structure of how state legislatures chose the senators.[3]

Furthermore, the House of Representatives began a proposal campaign in which it offered several iterations of an amendment for direct election of United States senators.[4] Unfortunately, these efforts were unsuccessful with the Senate refusing to proceed forward to a full vote. It was not until 1911, nearly 100 years after the first attempt to amend how we elect Senators, that the House of Representatives passed a joint resolution which allowed for direct election of Senators. The resolution required a change in the “race rider” included in the resolution. Once removed, the amendment was adopted, finally, and ratified in 1913.[5]

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

Specifically, the Seventeenth Amendment drastically changed the process by which a senator is chosen by amending Art. I, § 3 of the United States Constitution from “chosen by the Legislature thereof” to “elected by the people thereof.”[6] This significant change impacted government.

Furthermore, this slight change in verbiage of the Seventeenth Amendment allows a change in curing the vacancy of a senator as well. With the authorization of the state’s legislature, the governor may temporarily appoint a senator. When a vacancy arises, this power occurs and remains until a general election occurs. “Thirty-seven states fill Senate vacancies at their next regularly scheduled general election. The remaining 13 require that a special election be called.”[7] Since the Seventeenth Amendment was adopted in 1913, there have been 244 vacancies in the U.S. Senate with more than 40 appointments directly disregarding the Seventeenth Amendments’ popular vote election requirement.[8] Over and above this affront, other states have delayed election integrity, erroneously delivering 200 years of elected representation. Surprisingly, these practices have gone virtually unnoticed and/or unchecked for state compliance.

It is imperative that the text profiles the famous Illinois example of the Seventeenth Amendment corruption. In 2008, Senator Barack Obama resigned his senate seat to become the President of the United States, the Seventeenth Amendment’s Vacancy Clause emerged front and center. The Vacancy Clause states, “When vacancies happen in the representation of any State in the Senate, the executive authority of such State shall issue writs of election to fill such vacancies: Provided, That the legislature of any State may empower the executive thereof to make temporary appointments until the people fill the vacancies by election as the legislature may direct.” Then Illinois Governor Rod Blagojevich recognized his authority to appoint a senator to fill this vacancy. Typically, the appointment is a non-event as it occurs quite frequently within the United States. However, this vacancy became a test case for how abuse of power may cloud one’s judgment when executing gubernatorial senate appointments. Blagojevich saw an opportunity to raise his political and financial capital as he shopped the senatorial appointment opportunity around the state. Unfortunately for Blagojevich, federal agents recorded the conversations in which he engaged in these discussions.[9] Interestingly enough, the temporary appointment of Roland Burris (then Illinois attorney general) was deemed as accepted, although Blagojevich was arrested, tried twice and convicted of attempting to sell the political appointment for the Illinois senate vacancy. In an ironic twist in 2020, Republican President Donald Trump granted clemency to past Democratic Governor Rod Blagojevich. Perhaps, in time the country will determine the rationale behind this unlikely research.

It is with this history that we began our examination of the parts of the Seventeenth Amendment.

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

On July 15, 1913, Senator Augustus Bacon of Georgia was the first directly elected Senator. The following year marked the first time that all senatorial elections were held by popular vote.[10]

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT XVII

Part I

The Senate of the United States shall be composed of two Senators from each State, elected by the people thereof, for six years; and each Senator shall have one vote. The electors in each State shall have the qualifications requisite for electors of the most numerous branch of the State legislatures.

Each state, regardless of size, will have representation of two Senators. What is a Senator? According to Black’s, a senator is “[a} member of a senate.”[11] As Senators are members of the legislative branch, their authority can be found under Article I of the U.S. Constitution as previously stated. This section creates a new way of obtaining Senators. Formerly, Senators were chosen by the state legislatures, but from 1913 forward Senators were directly elected by the voters of their respective states. Further, the term of the elected Senator was set at six years, unless otherwise extended or removed due to other incidents. Finally and quite important, is the concept of one senator = one vote. Although the first section of the Seventeenth Amendment is straightforward, the second section is anything but straightforward. Nevertheless, Clopton and Art note “…the first two paragraphs of the Seventeenth Amendment work in tandem to guarantee that the people will have the right in all circumstances to elect their representatives in the U.S. Senate.”[12]

Part II

When vacancies happen in the representation of any State in the Senate, the executive authority of such State shall issue writs of election to fill such vacancies: Provided, That the legislature of any State may empower the executive thereof to make temporary appointments until the people fill the vacancies by election as the legislature may direct.

The second portion of the amendment has pressed the interpretation issue as it presents several perspectives to consider regarding senate vacancies. A vacancy is defined as “[a]n unoccupied office, post, or piece of property; an empty place.”[13] The text of the amendment identifies the vacancy of the representation of the office of a United States Senator, the governor must issue a court’s order directing the election commission to hold an election to fill the vacant senate seat. A colon follows the clause to indicate that there is a separation of two independent clauses within this portion of the amendment. These two independent clauses are interconnected, in that the second clause will demonstrate or provide an explanation for the first clause. The second clause explains that the vacancies must be filled if and only if the state legislature allow the governor, through the state constitution or other laws, to fill the vacancies for the time being. The legislature would only provide this power until an election for the vacancy may be held. According to Clopton and Art, “[t]he Seventeenth Amendment’s second paragraph promotes the same democratic reform in situations where Senate seats are left vacant midterm, while at the same time helping preserve the states’ equal representation in the Senate through temporary appointments.”[14] Therefore, Clopton and Art’s data collection supports the blatant state noncompliance of direct election of Senators pertaining how the vacancy occurred; how the vacancy was filled (temporary appointment, election or both); how much time the seat remained vacant; and how much time the people of the state were without an elected senator.

Part III

This amendment shall not be so construed as to affect the election or term of any Senator chosen before it becomes valid as part of the Constitution.

This part of the amendment reminds the reader that any Senator’s term currently in office at the time of ratification in 1913 will not be affected by the Amendment; however, going forward all Senators will be subject to vacancy and direct election.

Amendment XIX

Passed by Congress June 4, 1919. Ratified August 18, 1920

The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.

Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

100 Years and Counted: Women’s Movement Still Moving After 19th Amendment[15]

INTRODUCTION

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

The United States Women’s Suffrage fight was built upon the Abolitionist movement where women exhibited great political influence, in spite of their inability to obtain the right to vote.

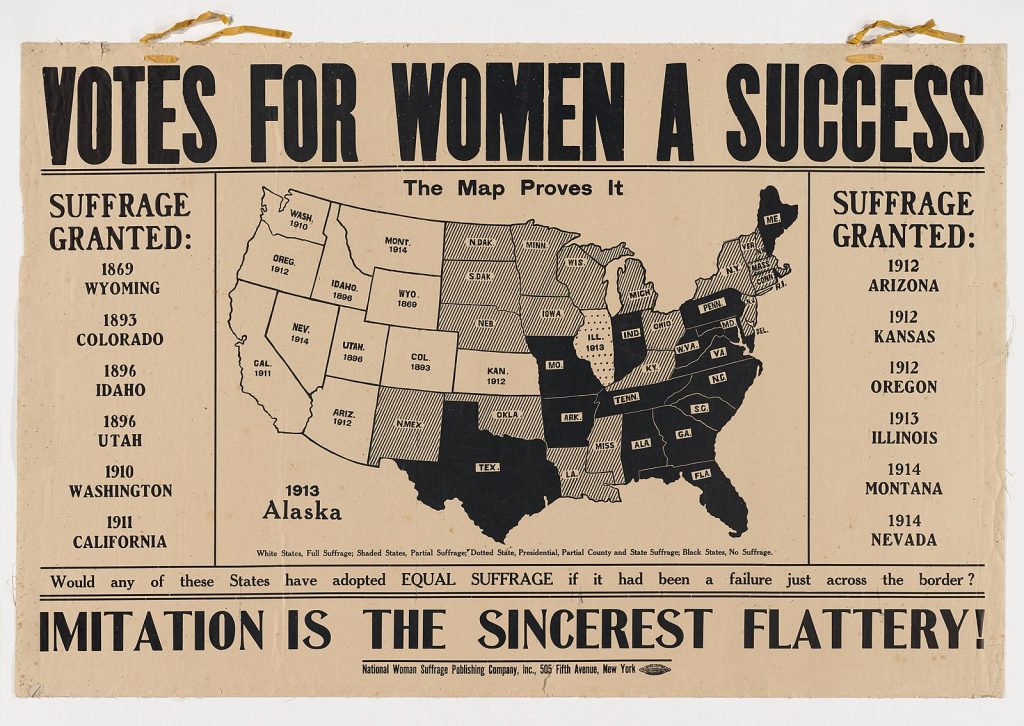

The original constitution called for freeholders or white men who were landowning citizens. Individuals who were void of property were considered to have no stake in the community according to the National Constitution Center. What becomes less clear within the women’s suffrage movement is that women were regarded as voters in the 1776 New Jersey Constitution and 1790 New Jersey election law. When taking the facts as a whole, the white males and their landowning characteristics this interpretation pointed to the interpretation that women were allowed to vote.[16] This particular moment led to what would be known as the women’s suffrage movement. Black’s defines women’s suffrage as “[t]he right of women to vote. In the United States, the right is guaranteed by the 19th Amendment to the Constitution.”[17] This limited women’s right to vote was halted in response to allegations of men dressing as women and thus, the formal disenfranchisement of women continued until 1920 when the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified. What is disenfranchisement? Black’s Law defines disenfranchisement as “[t]he act of taking away the right to vote in public elections from a citizen or class of citizens.”[18] Furthermore, Stanford Historian and Professor Freedman carefully identifies the intersectionality of the women’s suffrage movement, race, and class noting that the true advocacy for voting is rooted in the women who were advocates of the abolition of slavery.[19] Black and white women alike were engaged in the fight for human, civil, and political rights from the 1830s to the 1850s. Freedman explains that “[w]hile Black women sought freedom for their own race, some white women steeped in religious or moral training came to believe that slavery defied their ideals of womanhood and of justice.”[20] Because of this shared belief, white abolitionist women unapologetically spotlighted the rape and kidnapping of enslaved and free Black women leading to additional advocacy.

However, the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment served as a catalyst for advocates such as Susan B. Anthony to argue that the Fourteenth Amendment’s Privileges or Immunities Clause gave all women the right to vote. Anthony believed that women’s citizenship made it clear that no citizen should be denied the privileges and immunities of citizenship, including the right to vote.[21] To test her theory, Anthony tried to vote and was allowed to do so. Unfortunately, her vote was deemed illegal. Soon after she voted, she was arrested and convicted of illegally voting. Simultaneously in another state, voter Virginia Minor attempted the voting process as well, but was denied registration.[22] Ms. Minor’s actions led her to the courts using the Fourteenth Amendment’s justification. In Minor v. Happersett (1875), the Supreme Court of the United States held that women’s citizenship did not support the right to vote.[23] Thus, women began to look to other avenues to expand the women’s suffrage.

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

Since the inception of the United States of America, the clarion call of voter fraud has led the charge of the rationale for widespread, illogical, and constitutional disenfranchisement.

Similar to other marginalized groups, the right to vote for women did not occur easily and/or overnight. To receive the right to vote, women wrote, fought, protested, marched, lobbied, paraded, and practiced civil disobedience. They were misused, physically abused, taunted, and imprisoned. They silently demonstrated and even engaged in hunger strikes to highlight and showcase the barriers that women faced to gain their full citizenship rights. As previously noted in Chapter 11, women’s advocacy prior, during and after the Eighteenth Amendment, was key to the grass roots and organizational approach to Prohibition. In addition, women’s involvement at a national level for a victorious effort provided the necessary confidence for the advocacy, engagement and ultimately diligence to pursue their right to vote; however, it is equally important to remember that women’s right to vote did not apply to every woman.[24]

This is of special import, in that numerous women who would never benefit from this fight, still refused to allow the movement to proceed without their support. Namely, Ida B. Wells was cited with starting the first Women’s Suffrage Organization for Black women in 1913 – Chicago’s Alpha Suffrage Club.[25] Additionally, Sojourner Truth began appearing and speaking at suffrage gatherings from 1850 until her death in 1883. Meanwhile, Frances E. W. Harper organized and served as the Vice-President of the National Association of Colored Women.[26] It is essential to note for women, the right to vote was interconnected with equally important issues such as child care, equal pay, abolition of slavery, and prohibition. Most activists and champions recognized that these human and civil rights were intersectional and required attention if they were to be properly addressed.

As women began to center their efforts on suffrage, advocates believed the best path forward for their goals included a constitutional amendment. According to the National Archives, “[b]etween 1878, when the amendment was first introduced in Congress, and 1920, when it was ratified, champions of voting rights for women worked tirelessly, but their strategies varied.” As a result, New York adopted suffrage, President Woodrow Wilson pledged his commitment to the unanimous effort for the constitutional amendment and the country supported this stance.

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT XIX

Part I

The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.

Interestingly, the final verbiage of the Nineteenth Amendment included the concept of citizenry raised by Susan B. Anthony above. This portion of the amendment states all citizens without bar, reduction or diminution shall enjoy the rights afforded in the Fourteenth and Nineteenth Amendments. This citizenship and ultimately the vote can not be restricted based upon a citizen’s sex. Consequently, this portion of the amendment’s ratification provided the right to vote for white women.

Part II

Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

The verbiage in this constitutional amendment was employed to enable proper enforcement power by appropriate legislation. It reflects the language found in the 13th, 14th, 15th, 19th, 23rd, 24th, and 26th Amendments.

Amendment XXIII

Passed by Congress June 16, 1960. Ratified March 29, 1961.

Section 1

The District constituting the seat of Government of the United States shall appoint in such manner as Congress may direct:

A number of electors of President and Vice President equal to the whole number of Senators and Representatives in Congress to which the District would be entitled if it were a State, but in no event more than the least populous State; they shall be in addition to those appointed by the States, but they shall be considered, for the purposes of the election of President and Vice President, to be electors appointed by a State; and they shall meet in the District and perform such duties as provided by the twelfth article of amendment.

Washington, D.C. license plate, 2011[27]

Section 2

The Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

INTRODUCTION

Prior to the passing of the Twenty-third Amendment, residents of the District of Columbia (the seat of the government) were unable to cast a ballot. This ironic fact rang true until 1960, with the exception of the resident who maintained valid election registration in a state. Since the inception of the District of Columbia (DC), Congress has grappled with its treatment for purposes of representation.

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

The Twenty-third Amendment is the second fastest ratified amendment.

History reveals an uncertainty from the 1787 establishment of DC as the official seat of the government. According to the White House Historical Society, Congress directed and maintained exclusive control over the seat of the government via Art. 1, § 8, noting the Constitution states that Congress shall have the power “to exercise exclusive Legislation in all Cases whatsoever, over such District (not exceeding ten Miles square) as may, by Cession of particular States, and the Acceptance of Congress, become the Seat of the Government of the United States.”[28] To this end, DC was meant to be the framers’ compromise balancing the unpaid debt of the Revolution addressed in the Amendment XIV, § 4 and the location of the seat of the government. The framers wanted to ensure that the seat of government would exude nonpartisan, unbiased approach to politics excluding state influence and emphasizing federal control. However, National Constitution Center identified that as the years progressed beyond 1787, DC notes increased freedom from federal control with residents participating in statehood actions of levying and collecting federal and local taxes, armed forces service, election of a Mayor as well as a Council.[29]

Black’s Law Dictionary defines Statehood as “The condition of being a state, esp. one of the states in the United States.”[30] Proponents of statehood continue to rely on these activities as it emphasizes DC’s restrictions on Congressional representation due to the Twenty-third Amendment, but the issue remains that this representation is for a nonvoting delegate. Proponents of DC’s statehood suffered a slight setback when Congress adopted “The District of Columbia Voting Rights Amendment,” outlining political treatment of DC as a state, but failing with just 42% of the necessary States needed before the common clause of ratification occurred prior to the seven-year period similar to Amendments Eighteen, Twenty, Twenty-One and Twenty-Two.[31]

As it relates to the present day events, proponents for furtherance of representation in DC are involved in a continued push for statehood. Proponents note original arguments and evidence in support of efforts for the Twenty-third Amendment. Notably, the House of Representatives hearings in the 86th Congressional body of 1960 explains the initial purpose for the consistent campaign for those who reside in DC to have appropriate representation:

“ENFRANCHISEMENT OF RESIDENTS OF DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

The purpose of this. . . constitutional amendment is to provide the citizens of the District of Columbia with appropriate rights of voting in national elections for President and Vice President of the United States. It would permit District citizens to elect Presidential electors who would be in addition to the electors from the States and who would participate in electing the President and Vice President.

The District of Columbia, with more than 800,000 people, has a greater number of persons than the population of each of 13 of our States. District citizens have all the obligations of citizenship, including the payment of Federal taxes, of local taxes, and service in our Armed Forces. They have fought and died in every U.S. war since the District was founded. Yet, they cannot now vote in national elections because the Constitution has restricted that privilege to citizens who reside in States. The resultant constitutional anomaly of imposing all the obligations of citizenship without the most fundamental of its privileges will be removed by the proposed constitutional amendment. . .

[This] . . . amendment would change the Constitution only to the minimum extent necessary to give the District appropriate participation in national elections. It would not make the District of Columbia a State. It would not give the District of Columbia any other attributes of a State or change the constitutional powers of the Congress to legislate with respect to the District of Columbia and to prescribe its form of government. . . . It would, however, perpetuate recognition of the unique status of the District as the seat of Federal Government under the exclusive legislative control of Congress.”

Although DC’s population was high in 1960, it increased significantly from the 2010 census until the 2020 census.[32] In fact, the number grew by almost 100,000 in the last decade. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, this massive increase represents the seventh highest growth in the United States, which thus supporting and suggesting the need for DC to have separate statehood.[33]

On the other hand, critics of DC statehood are in agreement with proponents indicating that DC residents possess special privileges for DC residents only. As a result, critics posit that DC can not be admitted until and unless Amendment XXIII is repealed. The constitutional interpretation of Amendment XXIII being repealed for DC statehood has support for and against on both sides. Finally, critics point to the original Congressional authority in directing DC as unbiased and independent nature of state’s influence for it to work optimally. Perhaps, this subject may benefit from judicial interpretation as a Congressional chamber passed the second amendment for DC statehood. This occurred on April 22, 2021, with the Washington, D.C. Admission Act (H.R. 51) providing for the State of Washington, D.C. The country looks forward to seeing how this important and controversial amendment proceeds.

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT XXIII

Section 1

The District constituting the seat of Government of the United States shall appoint in such manner as Congress may direct:

A number of electors of President and Vice President equal to the whole number of Senators and Representatives in Congress to which the District would be entitled if it were a State, but in no event more than the least populous State; they shall be in addition to those appointed by the States, but they shall be considered, for the purposes of the election of President and Vice President, to be electors appointed by a State; and they shall meet in the District and perform such duties as provided by the twelfth article of amendment.

Washington, D.C. National Mall[34]

This section reminds the reader of the original appointment of DC as the seat of Government in Art. 1, §8 and its authority to govern DC as it sees fit. The seat of government is defined as “[t]he country’s capital, a state capital, a county seat, or other location where the principal offices of the national, state, and local governments are located.” Recall, the earlier elector discussion as mentioned in Chapter 13, Amendment XII regarding the President and Vice President. This section introduces an equivalency to what a state would receive in non-voting delegates for President and Vice President of the United States. Further, it provides the delegate numbers for a non-state which equal to the least populous state. These delegates are extra delegates from the states within the United States, but considered electors for Presidential elections. Rounding out the benefits and perks of these delegates is the process outlined in Chapter 13, Amendment XII.

Section 2

The Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

As aforementioned, the language in this section was included to provide the necessary enforcement power because this amendment was controversial. The words in the constitutional amendment enabled commensurate enforcement power by appropriate legislation. It mirrors the language found in the 13th, 14th, 15th, 19th, 23rd, 24th, and 26th Amendments. Thus the National Constitutional Convention reports that Congress enacted Public Law No. 87-389 in September 1961 providing the process for District of Columbia’s presidential elections.[35]

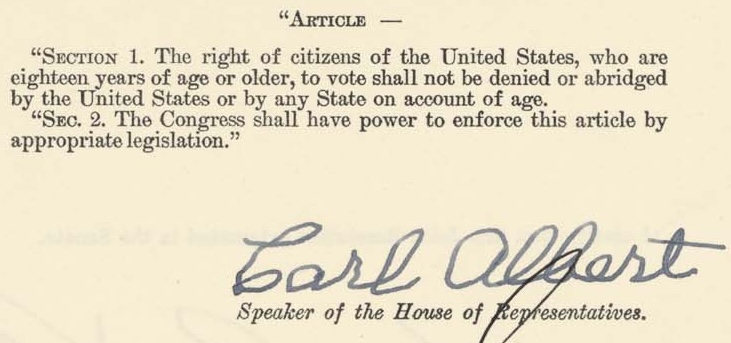

Amendment XXVI

Passed by Congress March 23, 1971. Ratified July 1, 1971. The 26th Amendment changed a portion of the 14th Amendment.

Section 1

The right of citizens of the United States, who are eighteen years of age or older, to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of age.

Section 2

The Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

INTRODUCTION

Amendment Twenty-Six was included as the last amendment in a collection and series of amendments which worked to expand significant change in voting rights in the United States Constitution. Prior to Amendment Twenty-six, persons who met the voting requirements over the age of 21 maintained the right to vote. Many of the previous amendments and legislation such as the Fourteenth, Fifteen, Nineteenth, and Twenty-fourth Amendments as well as the Civil Rights Act, Voting Rights Act and Women’s Suffrage movements helped the country gain the necessary support to provide voting rights for all women over 21 years old regardless of gender, race, and any additional barriers which voters may face.[36] Specifically, upon ratifying the original constitution in 1788, voting was mostly available for white, male, landowning citizens over 21 years old. More than eighty years later, former and freed slaves would gain the right to vote (but this gain was short-lived returning a century later). Moreover, more than 132 years later, white women would join the ranks of voters. Finally, 183 years later all remaining, young adults 18-20 would complete the eligible voters.[37]

Beginning in 1942, an uneven response to the rally for lowering the voting age emerged. Black’s Law Dictionary defines Voting as “[t]he casting of votes for the purpose of deciding an issue.”[38] Some states lowered the voting age from 21 to 18, while others refused to do so – creating some confusion and contention. In response, proponents for lowering the voting age pointed to another controversial topic – young people drafted for war. According to the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, cries for help began with World War II in 1941.[39] Proponents of lowering the age, began to analogize a young adult’s ability to be drafted in war with the young adults’ ability to vote. In 1942, Representative Jennings Randolph introduced legislation and explained that young adults (18-20) were capable of identifying governmental and political concerns relating to both war and voting.[40] Therefore, the young adults wanted to participate in both.

Proponents of lowering the voting age adopted a specific slogan “old enough to fight, old enough to vote.”[41] This popular slogan rang true during another war – The Vietnam War, when voting rights were revisited again. Due to the controversy surrounding the Vietnam War as well as the extension of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, Congress inserted a clause which lowered the voting age from 21 to 18 for all elections – federal, state and local. Remember, voting rights are typically in the purview of the State election boards per our earlier discussions.[42] In this instance, the states’ adversarial approach to lowering the voting age culminated in several court cases. The United States government filed a lawsuit against Idaho and Arizona attempting to force compliance with the act; while, Texas and Ohio filed claims that the government overstepped its legal authority to lower ages in elections.[43]

Therefore, the Supreme Court of the United States combined these cases in Oregon v. Mitchell (1970), addressing many issues including whether Congress can lower the voting age from 21 to 18 in federal, state and local elections.[44] Justice Hugo L. Black wrote the opinion in a 5-4 decision. Justice Black confirmed Congress’ ability to lower the voting age from 18-21 years old in federal elections for U.S. Congress, President and Vice-President.[45] Proponents of lowering the voting age, then turn their attentions to repudiating Oregon v. Mitchell (1970), by supporting a Congressional proposal for a constitutional amendment, Amendment XXVI, to settle the issue – lowering the voting age in all elections.

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

The ratification of Amendment XXVI added 11 million new eligible voters.[46]

In 2021, the country celebrated 50 years of this amendment. According to Tufts University’s Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE), this celebration came on the heels of the 25-point margin where voters 18-29 participated heavily in a monumental moment.[47] Then Senator Kamala Harris joined then Past Vice-President Joe Biden’s ticket and was elected as the first woman Vice-President as well as the first African-American and South Asian American to hold this office.[48] CIRCLE emphasizes the assistance young voters provided in all of the important battleground states to secure the White House for the Biden-Harris campaign.

Of equal note is what Oregon v. Mitchell (1970) stated regarding state and local elections. Congress lacks the power to force states to lower the voting age from 21 to 18 years old in state and local elections.[49] Thus, the legal, federal voting age is 18, state and local officials are anything but consistent on the voting age topic. For example, “…a third of the states allow those who are 17, but will be 18 by the general election, to vote in primaries.” Additionally, “…18 states and Washington, D.C., allow those who are 17, but will be 18 by the general election, to vote in primaries.”[50] Illinois allows voters to vote in the primaries prior to 18 years old. Furthermore, voters may be allowed to preregister for voting, if they are younger than 18 years old. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, “[p]reregistration is an election procedure that allows individuals younger than 18 years of age to register to vote, so they are eligible to cast a ballot when they reach 18…”[51] Pre-registrants must follow the state’s rules for application, but will receive a pending or preregistration status. When the pre-registrant turns 18, the individual is automatically added to the voter registration list and able to cast a ballot.[52] Again, this decision is left to the states for direction, so some states “16-year-olds to preregister, and others allow 17-year-olds to preregister. The remaining preregistration states do not establish a specific preregistration age limit but require the voter to be 18 the next general election.[53]

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT XXVI

Section 1

The right of citizens of the United States, who are eighteen years of age or older, to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of age.

Twenty-Sixth Amendment[54]

The language in §1 greatly reflects the language used in Amendment XV. Compare the discussion in Amendment XV which points to deny or abridge as reduction or minimization of voting rights based upon race. In Amendment XXVI, the reduction or minimization refers to age as opposed to age. Critics of Amendment XXVI most similarly align with Amendment XV. In comparison, this section of Amendment XXVI as well as Amendment XIV, §1 regarding voting rights residency raises issues for college students and what is their established domicile for voting purposes.[55] Additionally, the National Constitution Center acknowledges that this section serves to protect young adults 18-20 against special voting parameters unique only to their age group.[56] Therefore, some critics posit that the similarities of expansion enjoyed in Amendment XV are missing in Amendment XXVI.

Section 2

The Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

As a point of clarification, this section reflects the words which provided a suitable response to diverging opinions surrounding this amendment. It is recognized that proper laws, codes, and/or statutes are needed to support the implementation of this amendment. It reflects similar verbiage found in the 13th, 14th, 15th, 19th, 23rd, and 24th Amendments.

Amendment XXVII

Originally proposed September 25, 1789. Ratified May 7, 1992.

No law, varying the compensation for the services of the Senators and Representatives, shall take effect, until an election of representatives shall have intervened.

INTRODUCTION

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

Although Amendment XXVII was ratified in 1992, it was proposed with the Bill of Rights amendments in 1789. The ratification of this amendment took almost 200 years. It was the slowest amendment to be ratified in the United States Constitution.

Ironically Amendment XXVII, originally proposed by James Madison as the second amendment to the United States Constitution, became the last ratified amendment in 1992.[57] It is apparent that the forefathers considered the amendment and its impact, but it would not come to fruition for more than two centuries later.

Although this effort began in 1789, yes 1789 not 1989, only nine states had ratified Amendment XXVII until the power of a college student’s advocacy occurs.[58] National Public Radio explained that the bulk of the movement regarding this amendment did not occur until 1982. Then 19 year-old undergraduate student, Gregory Watson submitted a paper in his government class on Amendment XXVII.[59] Surprisingly, he received a C. This C was not your normal grade, because Watson decided he would lobby state legislatures until the amendment was ratified. At this juncture, Watson needed 29 states to ratify. He wrote letters and most of the responses did not agree with Watson’s position until … Senator William Cohen of Maine. Cohen was the first to secure his home state, Ohio’s ratification in 1983. Ohio’s ratification occurred more than 100 years later. Amendment XXVII became part of the Constitution when Michigan finally ratified in 1992.[60]

Finally, Bernstein examines an in-depth analysis as to how Amendment XXVII survived death, while other amendments failed greatly in the more than 200 years which it took to ratify it. The legacy, history and evolution of Amendment XXVII was due to three reasons why Amendment XXVII was uniquely positioned to discuss “amendment politics.”[61] Therefore, this amazing law review article combines the best and worst of the work, sweat, tears, and goodwill which surrounds the amendment process providing note-worthy insight into our constitution.

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT XXVII

No law, varying the compensation for the services of the Senators and Representatives, shall take effect, until an election of representatives shall have intervened.

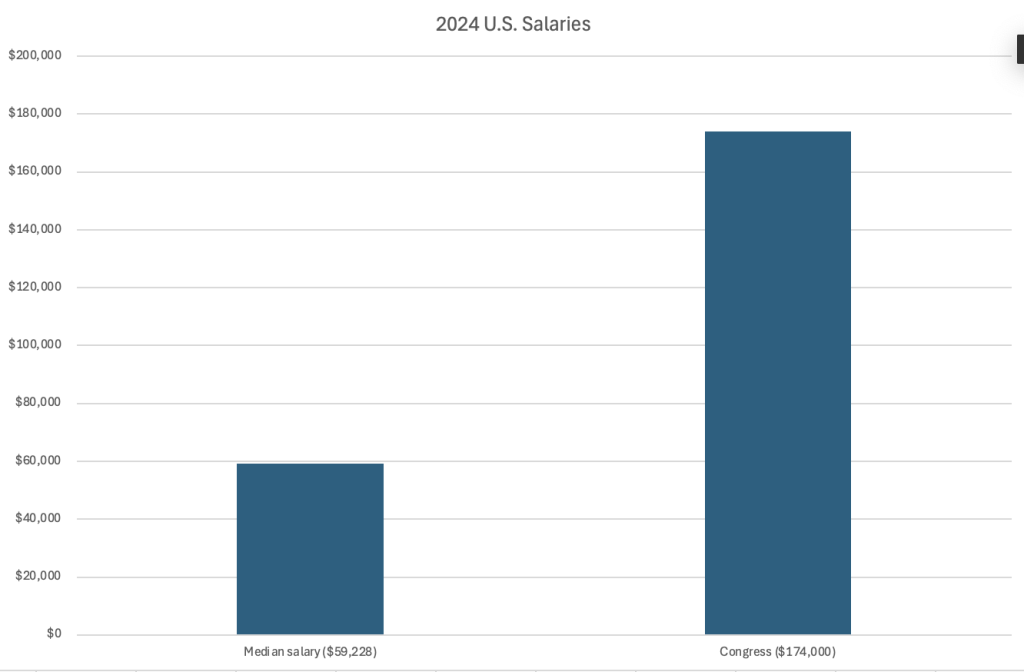

Twenty-Seventh Amendment – median U.S. salary vs. Congressional salary, 2024

This amendment speaks directly and frankly regarding how Congress is prevented from increasing the wages and/or salaries of its members until the subsequent election occurs. According to Strickland, the amendment passed after voters were introduced in 1989 to an almost $50,000 increase in the annual salaries of legislators.[62]

Strickland grapples with and determines that Amendment XXVII with its more than 200 years of ratification is constitutionally sound and established. Finally, this amendment was quietly accepted except for one sole case. In a Court of Appeals ruling, Boehner v. Anderson (1994), Congressman John Boehner vaguely addressed a violation of Amendment XXVII, when the court held “that the 1993 legislation eliminating the 1994 Cost-of-Living Adjustment (COLA) for Congress violates the twenty-seventh amendment” as it occurred after its ratification.[63] Thus, it appears the amendment process may be messy, elongated, strange, but well-established if it applies by the language of its proposal.

In closing, the authors remind you that the term amendment means change. In fact, the constitutional process has entertained approximately 11,848 amendments to the United States Constitution from 1798 to 2019 according to the United States Senate Legislative Records.[64] As a note to students, your voice can make a difference just as Gregory Watson’s did for Amendment XVII. In fact, our text consistently examined how the United States Constitution balanced federal, state and individual rights. As a result, Gregory Watson operationalized his individual rights and powers to change not one, but two amendments.

Fresh off his victory of Amendment XXVII, in 1995 Watson realized a peculiar fact about Mississippi and Amendment XIII. Watson researched and determined Mississippi never ratified Amendment XIII.[65] He lobbied and convinced the Mississippi Legislature to ratify the Amendment. Interestingly, a recording mishap would preclude Mississippi’s ratification until 2013.[66] Although this ratification was simply symbolic, I believe the 1.12 million African-American residents of Mississippi in 2013 would greatly appreciate this student’s symbolic push to ratify Amendment XIII.

Now that you have examined the history, story, legacy and process of the United States Constitution, how will you use your voice to help balance the federal, state, and individual rights to better our country?

Critical Reflections:

- To date, the longest Senatorial term was 51 years. Should Senatorial terms be limited? Why or why not?

- Should the District of Columbia be admitted to the union as the 51st State? Why or why not?

- Should individuals convicted of felonies be allowed to vote? Why or why not?

- History, Art & Archives, U.S. House of Representatives. “Counting the Electoral Vote - David Dudley Field Objects to the Vote of Florida,” https://history.house.gov/Collection/Listing/2005/2005-106-000/. Public domain. ↵

- U.S. Senate: Landmark Legislation: The Seventeenth Amendment to the Constitution. (2019, October 16). Senate.Gov. https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/generic/SeventeenthAmendment.htm ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- 17th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Direct Election of U.S. (2019, July 18). National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/legislative/features/17th-amendment ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- U.S. Senate (2019, October 16). ↵

- Vacancies in the United States Senate. (2023, July 10). https://www.ncsl.org/elections-and-campaigns/vacancies-in-the-united-states-senate ↵

- Zachary Clopton & Steven E. Art, "The Meaning of the Seventeenth Amendment and a Century of State Defiance," 107 Northwestern University Law Review 1181 (2013). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- U.S. Senate (2019, October 16). ↵

- SENATOR, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Zachary (2013). ↵

- VACANCY, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Zachary (2013). ↵

- Votes for Women a Success. Wikimedia Commons. Public domain. ↵

- 17th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Direct Election of U.S. (2019, July 18). National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/legislative/features/17th-amendment ↵

- SUFFRAGE, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- DISENFRANCHISEMENT, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Stanford University. (2020, August 12). 19th Amendment is a milestone, not endpoint. Stanford News. https://news.stanford.edu/2020/08/12/19th-amendment-milestone-not-endpoint-womens-rights-america/ ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Minor v. Happersett, 88 U.S. 162 (1875). ↵

- Id. ↵

- The 19th Amendment. (2020, May 14). National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/featured-documents/amendment-19 ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Qpqqqq. Washington, D.C. license plate, 2011. Wikimedia Commons. Public domain. ↵

- Clause XVII. (n.d.). LII / Legal Information Institute. Retrieved November 18, 2020, from https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution-conan/article-1/section-8/clause-17 ↵

- Interpretation: The Twenty-Third Amendment | The National Constitution Center. (n.d.). Constitutioncenter.org. Retrieved May 8, 2021, from https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/interpretation/amendment-xxiii/interps/155 ↵

- STATEHOOD, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Interpretation: The Twenty-Third Amendment (n.d.). ↵

- 2020 Census Data Shows DC’s Population Growth Nearly Tripled Compared to Previous Decade. (2021, April 26). [Press release]. https://dc.gov/release/2020-census-data-shows-dcs-population-growth-nearly-tripled-compared-previous-decade#:%7E:text=The%202020%20Census%20reports%20DC’s,growth%20rate%20in%20the%20nation ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Elisa.rolle. National Mall. Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 3.0. ↵

- Cait & Pozen, n.d. ↵

- Interpretation: The Twenty-Sixth Amendment | the national constitution center. (n.d.). Constitutioncenter.org. Retrieved March 2, 2021, from https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/interpretation/amendment-xxvi/interps/161 ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- VOTING, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- The 26th Amendment. (2018, May 3). National Museum of American History. https://americanhistory.si.edu/democracy-exhibition/vote-voice/getting-vote/sometimes-it-takes-amendment/twenty ↵

- Claire, M. (2020, November 11). How Young Activists Got 18-Year-Olds the Right to Vote in Record Time. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-young-activists-got-18-year-olds-right-vote-record-time-180976261/ ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Oregon v. Mitchell, 400 U.S. 112 (1970). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Williams, J. (2016, July 1). “Old enough to fight, old enough to vote”: The 26th amendment’s mixed legacy. U.S. News. https://www.usnews.com/news/articles/2016-07-01/old-enough-to-fight-old-enough-to-vote-the-26th-amendments-mixed-legacy ↵

- Trump push to invalidate votes in heavily black cities alarms civil rights groups. (2020, November 24). NPR. https://www.npr.org/2020/11/24/938187233/trump-push-to-invalidate-votes-in-heavily-black-cities-alarms-civil-rights-group ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Voting age for primary elections. (2023, July 10). https://www.ncsl.org/elections-and-campaigns/voting-age-for-primary-elections ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Joint Resolution Proposing the Twenty-sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Wikimedia Commons. Public domain. ↵

- Interpretation: The Twenty-Sixth amendment | the national constitution center. (n.d.). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Calabresi, S., & Teachout, Z. (n.d.). Interpretation: The Twenty-Seventh amendment | the national constitution center. The National Constitution Center. Retrieved April 24, 2021, from https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/interpretation/amendment-xxvii/interps/165 ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- The bad grade that changed the U.S. constitution. (2017, May 5). NPR. https://www.npr.org/2017/05/05/526900818/the-bad-grade-that-changed-the-u-s-constitution ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Bernstein, R. (1992). The sleeper wakes: The history and legacy of the Twenty-Seventh amendment. Fordham Law Review, 61, 497–557. https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3017&context=flr ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Boehner v. Anderson, 30 F.3d 156, 163 (D.C. Cir. 1994). ↵

- U.S. Senate: Measures proposed to amend the constitution. (2021, March 12). United States Senate. https://www.senate.gov/legislative/MeasuresProposedToAmendTheConstitution.htm ↵

- The bad grade, 2017 ↵

- Ibid. ↵