Chapter 1 – The Original United States Constitution & Its History – Part I

The Preamble, Article I, Article II

Richard J. Forst and Tauya R. Forst

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

1.1 Define the unfamiliar terms in Article I and Article II.

1.2 Identify the parts which comprise the United States Constitution.

1.3 Summarize the barriers to ratification of the Constitution.

1.4 Explain the need for the creation of the preamble.

1.5 Describe the six goals set forth in the preamble.

1.6 Explain what the Bill of Rights is addressing that the original Constitution omitted.

1.7 List some of the landmark cases challenging the Bill of Rights.

1.8 Compare powers granted in Article I with those granted in Article II.

1.9 Explain how checks and balances apply to the Constitution.

1.10 Describe the four judicial modes of appointment.

1.11 Explain the Vesting Clause.

1.12 Interpret the Impeachment Clause.

KEY TERMS

| Amendments | Constitution |

| Articles of Confederation | Constitutional Convention |

| Bicameralism | Doctrine of Incorporation |

| Bill of Rights | Executive/Executive Powers |

| Checks and Balances | Impeachment |

| Chevron Deference | Vesting Clause |

| Congress |

Historical Progression of Constitutional Interpretation

| DATE | 1776 | 1789 | 1791 | 1803 | 1857 | 1860 | 1863 | 1861-1865 | 1865 | 1868 | 1870 | 1896 | 1920 | 1954 | 1961 | 1963 | 1965 | 1966 | 1973 | 2013 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EVENT | DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE | UNITED STATES CONSTITUTION RATIFIED | BILL OF RIGHTS RATIFIED | MARBURY v. MADISON | DRED SCOTT v. SANDFORD | ABRAHAM LINCOLN ELECTED PRESIDENT | LINCOLN SIGNS EMANCIPATION PROCLAMATION | AMERICAN CIVIL WAR BETWEEN NORTHERN AND SOUTHERN STATES | 13TH AMENDMENT IS RATIFIED | 14TH AMENDMENT IS RATIFIED | 15TH AMENDMENT IS RATIFIED | PLESSY v. FERGUSON | 19TH AMENDMENT IS RATIFIED | BROWN v. BOARD OF EDUCATION | MAPP v. OHIO | GIDEON v. WAINWRIGHT | VOTING RIGHTS ACT ENACTED BY CONGRESS | MIRANDA v. ARIZONA | ROE v. WADE | SHELBY COUNTY v. HOLDER | DOBBS v. JACKSON WOMEN'S HEALTH | |

| SIGNIFICANCE | American colonists declare independence from Great Britain | Replaces Articles of Confederation; establishes supremacy of central government, three branches of government, separation of powers | Limits power of federal government, guarantees individual rights and freedoms to the people | Establishes power of judicial review by Courts over laws and statutes that violate the Constitution | Held that blacks are not entitled to American citizenship | Anti-Slavery, pro-Union President elected, resulting in Southern states seceding from the Union | President declares that slavery is illegal, and all persons held as slaves must be freed | 600,000+ Americans are killed; Secession is defeated; slavery is to be abolished in Southern states | Slavery is legally abolished in all States | Grants birthright citizenship for first time; Applied due process and equal protection guarantees to the States | Guarantees right to vote to all male citizens, regardless of race, color or previous condition of servitude | Established "separate but equal" doctrine for public facilities and accommodations | Established guarantee of Women's Right to Vote | Overruled Plessy v. Ferguson; declared "separate but equal" to be inherently unequal; laws establishing segregation are unconstitutional | Held that all evidence obtained by searches and seizures in violation of the 4th Amendment is inadmissible in a state court (the "exclusionary rule") | Held that 6th and 14th Amendments require States to provide attorneys to indigent criminal defendants | Act enforces 15th Amendment, outlaws discriminatory practices in voting, requires states with history of discrimination to obtain "preclearance" before changing voting rules | Held that 5th Amendment requires law enforcement officials to advise suspects of their right to remain silent and obtain an attorney during interrogations while in police custody. | Extended right of privacy through 14th Amendment to establish a limited right to an abortion under a trimester system | Held that Section 4 of Voting Rights Act of 1965 is an unconstitutional violation of the power to regulate elections that the Constitution reserves for the States | Overruled Roe v. Wade, held that Constitution does not confer an individual's right to an abortion |

Refer to this chart as you read each chapter of the textbook. It will provide the historical context needed to understand why the Constitution has been amended, and how it has been interpreted over time. Cases listed above are all opinions of the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS).

INTRODUCTION TO PREAMBLE

Black's Law Dictionary defines a "constitution" as, "1. The entire plan or philosophy on which something is constructed. 2. The fundamental and organic law of a country or state that establishes the institutions and apparatus of government, defines the scope of governmental sovereign powers, and guarantees individual civil rights and civil liberties; a set of basic laws and principles that a country, state, or organization is governed by. 3. The written instrument embodying this fundamental law, together with any formal amendments."[1]The original United States Constitution was planned, proposed, negotiated, created, and ultimately drafted by men. It was not a holy text that came down from on high on two tablets or through the words of a prophet inspired by the Creator. Instead, it was the product of human motivations and political considerations. As is true of any human creation, the Constitution was flawed. As Justice John Paul Stevens (2014) has noted, important imperfections in its text were the product of compromises that were certain to require that changes will be made in the future.[2] Changes or amendments as identified in the United States Constitution is defined by Black's Law Dictionary as "[a} formal and [usually] minor revision or addition proposed or made to a statute, constitution, pleading, order, or other instrument; [specifically], a change made by addition, deletion, or correction; [especially], an alteration in wording."[3] Hence, since its inception in 1789, the Constitution was amended 27 times, as well as interpreted and re-interpreted by Courts, Legislatures, and Executives ever since, over and over again.

So, how do we better understand this impressive document, the supreme law of the land in this country? Let's start at the very beginning.

PREAMBLE

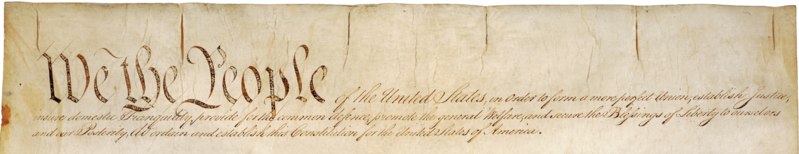

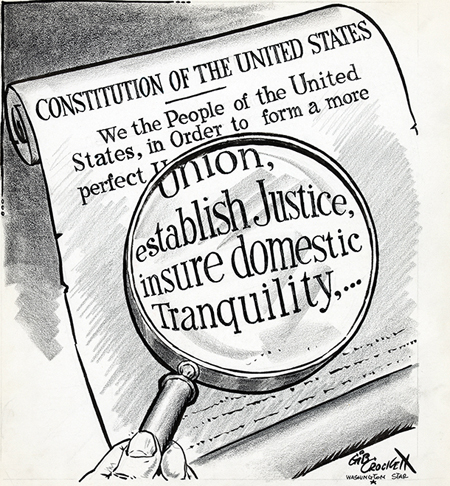

We the People of the United States, in order to form a More Perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common Defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

A cropped and digitally modified version of the first page of the United States Constitution showing only the preamble.[4]

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

The framers purposefully crafted a Preamble at the Constitutional Convention which is defined as "[a} deliberative assembly that consists of delegates elected or appointed from subordinate or constituent organizations within a state or national organization, or elected directly from the organization's membership or from defined geographic or other constituencies into which the membership is grouped, and that [usually] exercises the organization's highest policymaking authority."[5] The Preamble was both brief and vague. During the Civil War, the Southern states interpreted the three opening words to mean "We the States." But the framers, anticipating an ever-changing country, were careful to use the words "the People," rather than "the male white land owners" or "the qualified voters" to allow for future interpretations of "the People."[6]

In the Preamble, the framers of the Constitution set forth six goals:

- Form a More Perfect Union

- Establish Justice

- Insure Domestic Tranquility

- Provide for the Common Defense

- Promote the General Welfare

- Secure the Blessings of Liberty

ANALYSIS OF PREAMBLE

1. Form a More Perfect Union

United States flag[7]

The United States, until 1787, was governed by the tenets of the Articles of Confederation. The Articles of Confederation was "[t]he instrument that governed the association of the 13 original states from March 1, 1781, until the adoption of the U.S. Constitution (September 17, 1787)."[8] After the Revolutionary War, the Articles of Confederation were ratified in 1781 with a sense of urgency. The Revolutionary War, fought from 1775 to 1783, was also known as the American Revolution or the American War for Independence. The war arose from growing tensions between residents of Great Britain's 13 North American colonies and the colonial government, which represented the British crown.[9] Under the Articles of Confederation, the states remained sovereign and independent, with Congress as the last resort to settle disputes between the states. Congress or the United States Congress, is defined as "The legislative body of the federal government, created under U.S. Const. art. I, § 1 and consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives."[10] The Articles did not give the central government the ability to levy taxes and regulate commerce. George Washington called the Confederation “little more than a shadow without the substance.”[11]

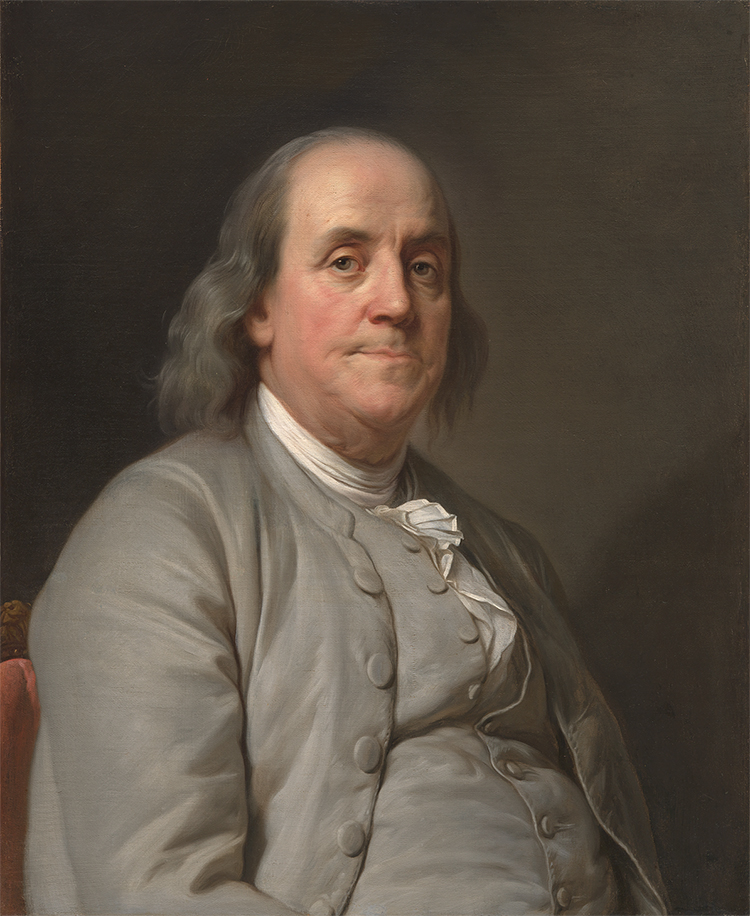

As a result, the Founders of our country, such as George Washington, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and Benjamin Franklin, decided to meet for a Constitutional Convention in 1787. The Convention was held in secret in Philadelphia where its stated purpose was to “revise the Articles of Confederation,” not to do away with them.[12] Franklin, never an alarmist by nature, nonetheless realized the significance of the moment. He wrote to Thomas Jefferson (then an ambassador to France) that from what he knew of the delegates, they seemed to be men of prudence and ability. Franklin remarked “I hope good from their meeting."[13] But the risks were great.

He added, “If it does not do good it must do harm, as it will show that we have not wisdom enough among us to govern ourselves, and will strengthen the opinion of some political writers that popular governments cannot long support themselves."[14]

Benjamin Franklin - American author, scientist, and statesman[15]

At the time of the Convention, the effective power in the country was dispersed and located in several states, “controlled by ruling groups not at all anxious to see that power diminished."[16] This dispersion of power resulted in unending battles between the states over trade, tariffs, and debts, all of which greatly concerned the Founders. Commercial disputes among the States, which Madison described to Thomas Jefferson as “the anarchy of our commerce,” were symptomatic of underlying flaws in the political framework of the Articles of Confederation.[17] But Madison had a solution in mind.

"Kowal and Codrington’s text makes clear that the beauty of this nation’s history is that even in times of deep division and extreme partisanship, citizens can band together to expand democracy and improve our governance by amending the Constitution. Our democracy clearly demands that the residents of the territories be included in the democratic process of the federal government. The People’s Constitution provides the tools to achieve that goal, and also highlights potential pitfalls for this endeavor."[18] It is now up to all of us to pick up the burden of democracy and continue working toward the promise of “a more perfect Union.”[19]

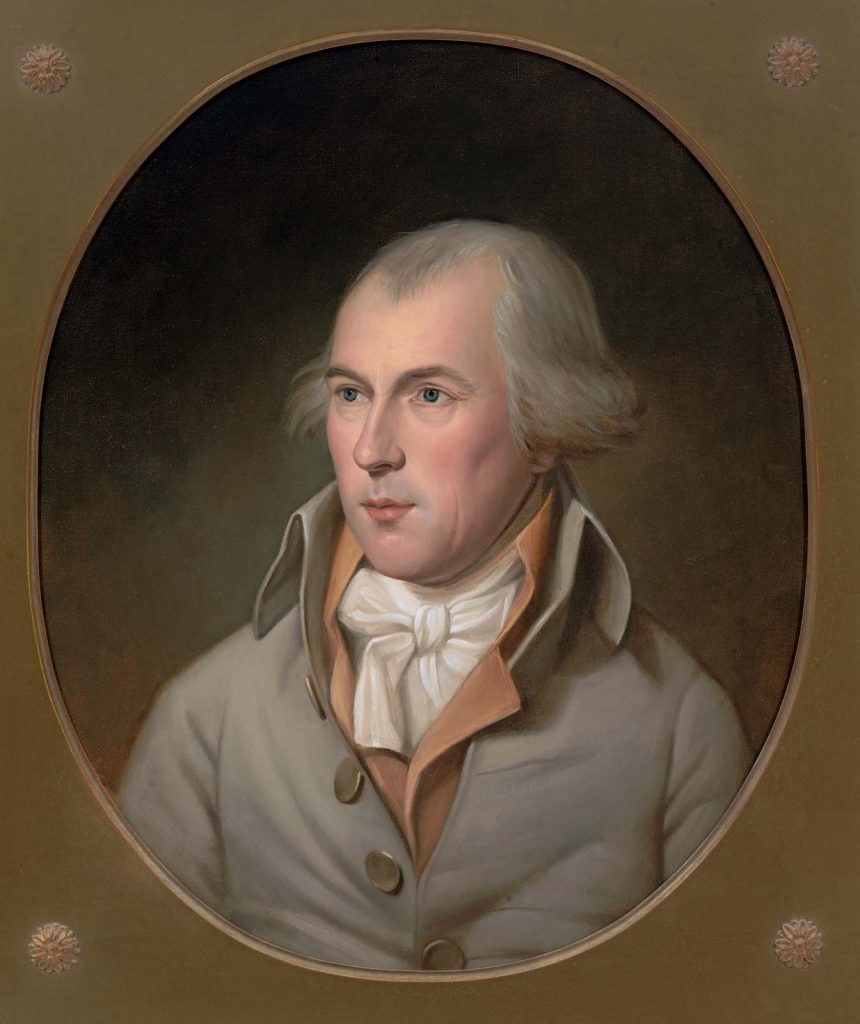

James Madison - 4th President of the United States, 1809-1817[20]

James Madison’s great contribution “consisted of a master theory and a master plan.” The plan was “Federalism,” that is, national supremacy.[21]

This plan for national supremacy would prove to be far more than mere revision of the Articles, and the Framers knew ratification would require some finesse. The Convention was held in secret because there was no popular will and consensus in favor of it. The popular will had to be “sought, cultivated, and labored after."[22] Under the Articles of Confederation, each state was represented equally in Congress, whether their populations were large or small. Smaller states intended to preserve that system. In fact, the Delaware delegates were forbidden by their State to agree to any change. But at the Convention, Benjamin Franklin submitted a compromise motion to create two houses of the legislature: (1) The higher to allow each state equal representation and (2) The lower to allow for proportionate representation in each state, so that states with larger populations would have the greater power to legislate.[23] With this change, Delaware became the first state to ratify the Constitution.

2. Establish Justice

United States Courts Constitution Day 2012[24]

Ironically, after boldly setting forth “Establish Justice" as the second goal of the Constitution, the Framers purposefully limited the franchise by excluding the majority of adults from voting. Only white male landowners were enfranchised. Interestingly, Benjamin Franklin was the primary drafter of the Pennsylvania State constitution. This document was considered radical for its time because it granted voting rights to ALL white men, not just the wealthy and landowning class.[25]

The 1790 Census revealed that 17.8% of the population was enslaved, and therefore, disenfranchised.[26] According to Black's Law Dictionary, disenfranchise means "[t]o deprive (someone) of a right, [especially] the right to vote; to prevent (a person or group of people) from having the right to vote."[27] About half of the remaining population were women, who did not partially gain the right to vote until the 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920.[28] Furthermore, “Jim Crow" laws enacted after the passage of the 15th amendment created insurmountable barriers to voting. By the late 1870s, discriminatory practices were used to prevent black men from exercising their right to vote, especially in the South.[29] After the Voting Rights Act of 1965, legal barriers which denied Black Americans their right to vote under the 15th Amendment were outlawed at the state and local levels.[30] (Note: Sections 4(b) and 5, the enforcement and preclearance provisions of the Voting Rights Act, required states to seek preclearance by the United States Department of Justice for changes in their voting procedures were found to be unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in Shelby County v. Holder, 133 S. Ct. 2612 (2013). As a result, in 2021, nineteen states enacted laws establishing voting restrictions that under the Voting Rights Act of 1965, would have required preclearance. In the first 25 days of 2023, 32 states introduced at least 150 bills aimed at making it harder to vote.)[31]

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

Fascinating Facts About The Constitutional Convention.

- Of the 55 delegates from the American colonies, 31 were lawyers.[32]

- Two founding fathers and future Presidents were not at the Convention and did not sign:

- Thomas Jefferson was ambassador to France.

- John Adams was ambassador to Great Britain.

- The only future Presidents to sign were James Madison and George Washington.

- According to Meacham (2013), Jefferson wrote to Adams, "It is really an assembly of demigods" (p. 211).[33]

- The Convention ended when 39 delegates from 12 states signed the Constitution. Alexander Hamilton was the only one of the three New York delegates to sign.[34]

According to the 2010 Census, 72.4% of the population were white and roughly half of those were male.[35] Note that the majority of white voters have supported the Republican candidate in every presidential election since 1968 (while Democratic candidates have won the popular vote in 7 of the last 8 presidential elections).[36] If only white male landowners were allowed to vote in the modern era, as was the case in 1790, Republicans would easily capture the White House and control of Congress in one election after another. If Americans had the same structure in place as the country had at the time of ratification of our Constitution, we would likely not recognize our own country today.

The words “democracy” and “slavery” do not appear in the original Constitution. But the delegates to the Convention recognized the existence and legitimacy of slavery by including a compromise between the slave-owning states and those with few slaves, counting slaves as 3/5 of a person for representation purposes.[37] In 1800 the 3/5 compromise was a slave “bonus" which gave presidential candidate Thomas Jefferson of Virginia more than the eight votes that provided his margin of victory over John Adams of Massachusetts in the Electoral College. This margin solidified Jefferson as our third President.[38] The word “slavery” first appeared in the Thirteenth Amendment, enacted in 1865. The issue was so explosive at the Convention that the word “slavery" did not appear in the final document, replaced by the euphemism of people “held to service or labor."[39]

3. Insure Domestic Tranquility

Learning from the Source: Preamble to the Constitution Image Sequencing[40]

Delegates to the Constitutional Convention had a financial interest in the establishment of a stable federal government.[41] The country was virtually bankrupt as the federal government and state governments found it impossible to retire the gargantuan debt inherited from the Revolutionary War concluded just a few years earlier. Commercial disputes among the States were symptomatic of underlying flaws in the political framework of the Articles of Confederation.[42] Correcting those flaws became the primary motivation for delegates to convene in Philadelphia.

The Framers foresaw the perils of requiring a supermajority (60% or 67%) to pass legislation in Congress, and elected to require only a bare majority in both chambers of Congress.[43] The Senate began to require a supermajority to cut off debate (the “filibuster”) in 1837, five decades after the Constitutional Convention. The Articles of Confederation had required a supermajority vote for most categories of legislation, which paralyzed the government. In Federalist 22, Alexander Hamilton addressed this, noting, “What at first sight might seem a remedy, is in reality a poison."[44] The Senate's supermajority requirement persists to this day. Many legislators continue to advocate for a return to majority rule as more legislation passes in the House but dies in the Senate for lack of supermajority support.[45]

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

Adam Jentleson, a former deputy chief of staff to Senator Harry Reid, states one of the biggest misconceptions about the filibuster, is that it encourages bipartisanship. Further, he states that in fact the filibuster does the opposite because it gives the party that’s out of power the means, motive and opportunity to block the party that’s in power from getting anything done.[46]

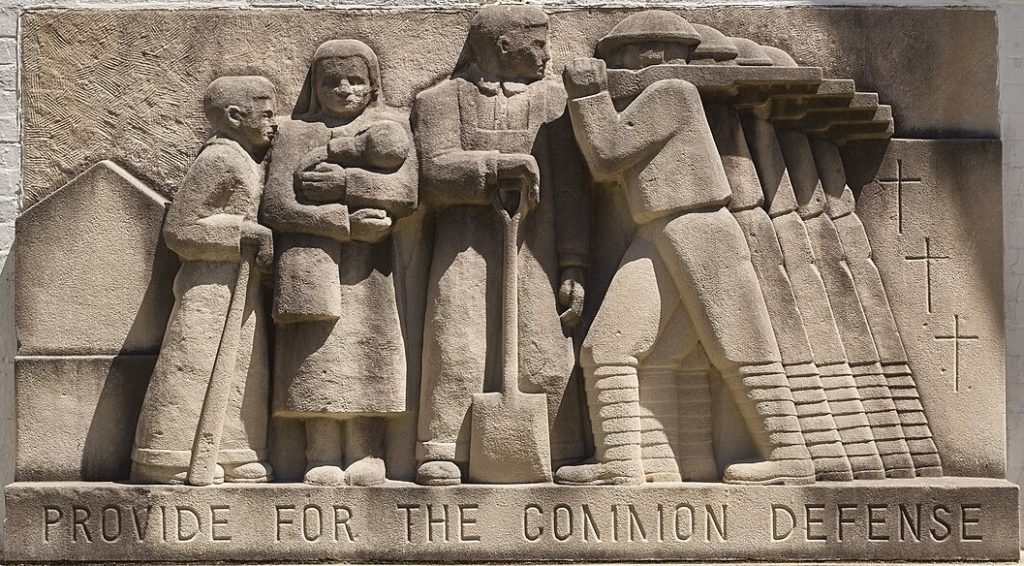

4. Provide for the Common Defense

Provide for the Common Defense[47]

The delegates to the Convention quickly and unanimously chose General George Washington to be the president of the Convention.[48] He was a past commander of the victorious Continental Army who secured America's independence from Great Britain.[49] The delegates recognized that providing for the common defense started with resolving the issue of executive authority, which was dangerously lacking under the Articles of Confederation. For four long months prior to the actual Convention, the best minds in the country met with Washington and spelled out in great detail what the country thought it needed in the way of executive authority. Additionally, they pondered the limits on the authority that the country might be expected to insist on during debate for ratification. The balance struck by the delegates was almost certainly arrived at from what they already knew of Washington.

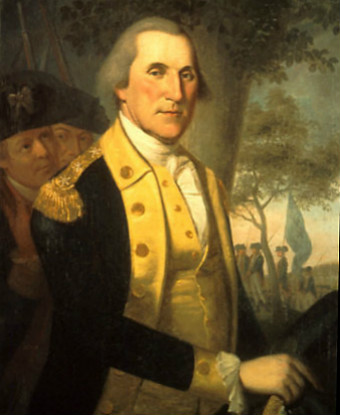

George Washington - 1st President of the United States of America, 1789-1797, National Park Service, Independence National Historical Park [50]

The executive powers probably would have been more limited had the delegates disagreed with Washington as the executive.[51]

Alexander Hamilton argued for a chief executive to be elected for life (by white male landowners).[52] Benjamin Franklin argued for executive power to be shared by an executive council.[53] The executive power is defined as "[t]he power to see that the laws are duly executed and enforced. Under federal law, this power is vested in the President; in the states, it is vested in the governors. The President's enumerated powers are found in the U.S. Constitution, art. II, § 2; governors' executive powers are provided for in state constitutions."[54] Other delegates argued for a single seven-year term for the executive. The delegates compromised with a four year term renewable by election of the electoral college and the compromise remains today.[55]

Having now resolved the issue of executive terms, the delegates remained sensitive to the popular distrust of sovereign authority. After all, sovereign authority prompted the American rebellion against the British king. The delegates sought to limit the power of the executive and balance it with the power of the people's elected representatives in the legislature. Thus, they required the executive to seek the “advice and consent" of one branch of the legislature, the Senate, before concluding a treaty with a foreign power.[56] The procedure by which this would occur was not plainly stated, and this was promptly put to the test.

Washington, in August of 1789, sent a message to the Senate that he would meet the Senate the next day “to advise with them on the terms of the treaty to be negotiated with the Southern Indians."[57] After he read a report that Washington carefully prepared, Vice-President John Adams asked the Senate, "Do you advise and consent?"[58] To Washington's frustration, the Senators responded with silence.[59] They appointed a committee to study the matter, met again with Washington the following week, and the Senators promptly gave their consent. It became apparent from this episode that the “advise and consent" power actually was not advice at all, but merely whether to consent or not. From that point forward, no Presidents met with the Senate to discuss treaty negotiations.[60]

The delegates purposefully divided the power of war between the executive and the legislature. Article I, §8 gives Congress the power to declare war and raise and support the armed forces. Article II, §2 appointed the President as Commander in Chief of the armed forces of the country. The tension between these two powers has caused debates about the extent of executive power to conduct wars throughout American history.

James Madison later insisted, "No Constitution ever would have been adopted if the debates were made public."[61]

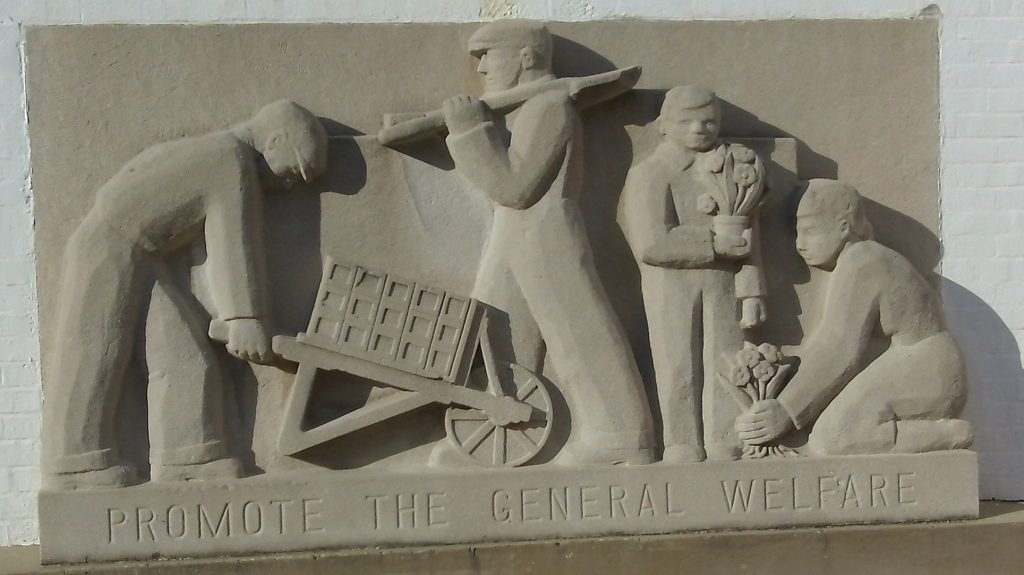

5. Promote the General Welfare

Promote the General Welfare[62]

Recall, Benjamin Franklin submitted a compromise motion at the Constitutional Convention to create two houses of the legislature. The higher house to allow each state equal representation, while the lower would allow for proportionate representation in each state. This compromise gave states with larger populations greater power to legislate. But James Madison countered, “The plan now to be formed will almost certainly be defective, as the Confederation has been found on trial to be. Amendments will therefore be necessary, and it will be better to provide for them, in an easy, regular and Constitutional way than to trust in chance and violence."[63] Madison pointed to the experience in drafting State Constitutions. In Madison's home state of Virginia, the leaders there were first to enact a Constitution. Unfortunately, Virginia allowed for no amendments. Although defects were apparent in the document, there were no provisions for its leaders to do anything about it. Thus, Article V was made part of the Constitution.[64]

Article V of the Constitution provides two ways to propose amendments to the document. Amendments may be proposed either by the Congress, through a joint resolution passed by a two-thirds vote, or by a convention called by Congress in response to applications from two-thirds of the state legislatures. There have been over 11,000 amendments proposed since 1789, of which 27 have been ratified.[65]

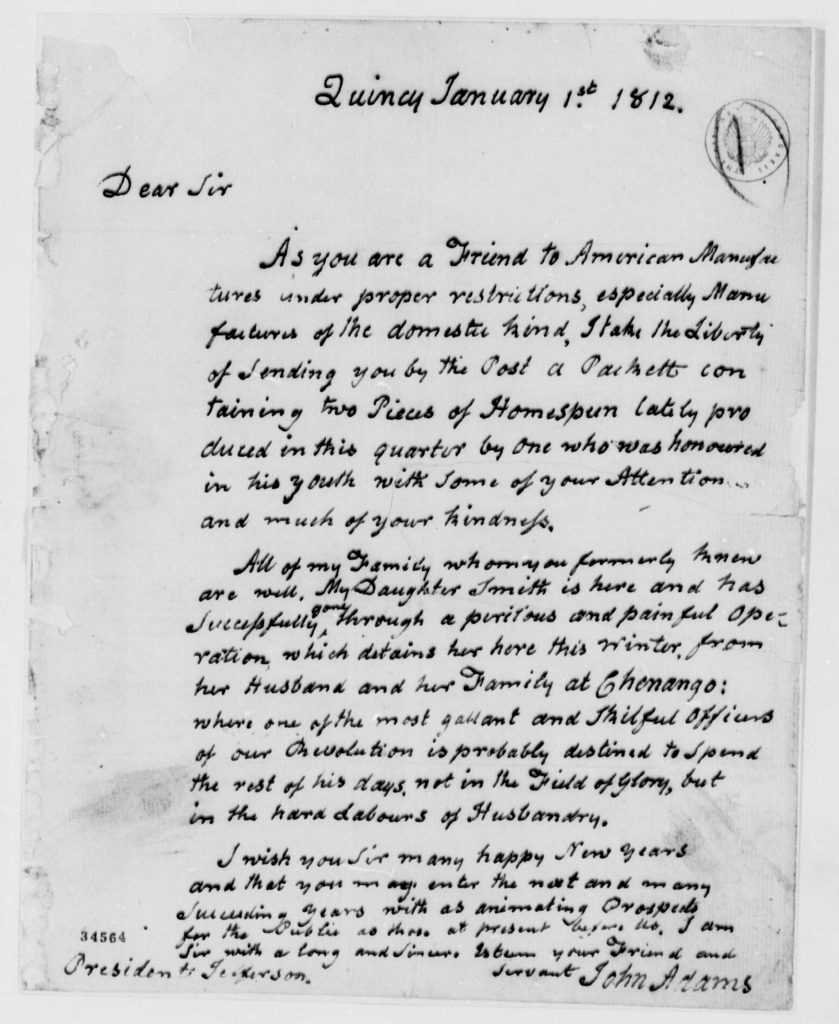

John Adams, 2nd President of the United States, 1797-1801 wishes Thomas Jefferson, 3rd President of the United States, 1801-1809, ‘Many Happy New Years’ on January 1st, 1812[66]

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

John Adams, upon reading the final draft of the Constitution to be presented to the States for ratification, wrote to Thomas Jefferson: “What think you of a Declaration of Rights? Should not such a thing have preceded the model?"[67] Jefferson wrote Adams, but said nothing about a bill of rights. His great concern was the office of the President, which struck him as “a bad edition of a Polish king…I wish that at the end of the four years, they made him ever ineligible a second time."[68] Adams responded, “You are afraid of the one, I, the few…You are apprehensive of monarchy, I, of aristocracy. I would therefore have given more power to the President and less to the Senate."[69]

6. Secure the blessings of Liberty

Secure the blessings of Liberty[70]

The framers understood that the central fact of civic life, by which every political collision and its outcome could be understood, was the irreconcilable antimony of liberty and power. Power is by its nature aggressive, encroaching, unstable; liberty is passive, exposed, and subvertible. The lust for power, left unrestrained, is the most dangerous of human appetites; the safeguarding of liberty (or law, or right) requires unsleeping vigilance, virtue and will.[71]

In the closing days of the Constitutional Convention, after all the major compromises were made and the form essentially set, George Mason of Virginia had proposed that the new Constitution be prefaced by a bill of rights. The Bill of Rights is defined as "[a] section or addendum, [usually] in a constitution, defining the situations in which a politically organized society will permit free, spontaneous, and individual activity, and guaranteeing that governmental powers will not be used in certain ways; [especially], the first ten amendments to the U.S. Constitution."[72] It was voted down. It had been a long hot Philadelphia summer, in a world without air conditioning, but Mason drafted a set of objections to the Constitution which were subsequently printed and circulated throughout all the states.[73] In the battle for ratification of their Constitution in the months that followed, the delegates found again and again that the point at which they were most vulnerable was their neglect of a bill of rights. The compromise was reached in Massachusetts, then other states were to ratify the Constitution with a list of recommended rights, largely drafted by James Madison.[74]

George Mason, United States Statesman[75]

The result--involving freedom of speech, press, and conscience, trial by jury, security of person and property, and various other rights--was referred to a committee for much debate and finally passed by both houses of Congress in late September of the same year, and then ratified as the first Ten Amendments of the Constitution two years later.[76]

BILL OF RIGHTS

'“The People” {of the United States} have made twenty-seven distinct modifications (better known as amendments). Some of those amendments were aimed at curing procedural deficiencies, while others acknowledged the humanity of an entire segment of the North American population, which was consciously denied by the Constitution’s Founders, text, and judicial interpretations of the same.[77]

Amendment I

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

Amendment II

A well-regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed.

Amendment III

No soldier shall, in time of peace be quartered in any house, without the consent of the owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.

Amendment IV

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

Amendment V

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a grand jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the militia, when in actual service in time of war or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offense to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.

Amendment VI

In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the state and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the assistance of counsel for his defense.

Amendment VII

In suits at common law, where the value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial by jury shall be preserved, and no fact tried by a jury, shall be otherwise reexamined in any court of the United States, than according to the rules of the common law.

Amendment VIII

Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.

Amendment IX

The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.

Amendment X

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the states respectively, or to the people.

Drafted by the majority of the delegates, the Constitution did not receive unanimous support. But, in order to encourage the states to unanimously ratify the result, the delegates agreed to the following statement: “Done in Convention, by the unanimous consent of the States present the 17th of September."[78] George Washington signed first, followed by 37 others, state by state. Thus the infant Constitution was presented to the 13 states for ratification in 1787. Proponents of the Constitution (the “Federalists"), namely, Hamilton, Madison and John Jay (soon to be our first Chief Justice) drafted closely reasoned essays in support of this effort to implement a strong central government known as “The Federalist Papers."[79] Madison's addition of a Bill of Rights proved to be crucial to ratification by the states, as the Rhode Island and North Carolina legislatures overcame their initial reservations and notified Washington that they were satisfied by the guarantees of individual rights.[80]

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

The Convention provided a positive answer to the question that Alexander Hamilton, in defending the new Constitution, had pondered in Federalist No. 1. “Whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force."[81]

INTRODUCTION TO THE CONSTITUTION

The first Ten Amendments of the Constitution, the “Bill of Rights," were originally conceived as limitations on the powers of the newly created national government. Under this original conception of the Bill of Rights, citizens seeking legal protections against actions of state and local governments looked to their state constitutions and courts for relief, as the Supreme Court held in Barron v. Baltimore (1833).[82] However, over the course of the past 125 years, the Supreme Court has extended the Bill of Rights to the states in a series of cases, on the basis of the “Doctrine of Incorporation." Through this doctrine the provisions of the Bill of Rights were incorporated within the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Doctrine of Incorporation or incorporation doctrine is defined as "[t]he incorporation doctrine is a constitutional doctrine through which parts of the first ten amendments of the United States Constitution (known as the Bill of Rights are made applicable to the states through the Due Process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Incorporation applies both substantively and procedurally."[83] For example, in Wolf v. Colorado (1949), the Court held that the freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures is “implicit in the concept of ordered liberty" and as such enforceable against the States through the Fourteenth Amendment.[84]

The following is a list of all the Supreme Court incorporation cases, and the relevant Amendment thereby enforced against the States:

First Amendment protections of free speech and free press, Gitlow v. New York, 268 U.S. 652 (1925).

First Amendment protection of free exercise of religion, Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U.S. 296 (1940).

First Amendment establishment of religion, Everson v. Board of Education, 330 U.S. 1 (1947).

First Amendment freedom of assembly, DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 U.S. 353 (1937).

First Amendment right to petition for redress of grievances, Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U.S. 229 (1963).

Second Amendment right to keep and bear arms, McDonald v. Chicago, 561 U.S. 3025 (2010).

Fourth Amendment protection against unreasonable searches and seizures, Wolf v. Colorado, 338 U.S. 25 (1949).

Fourth Amendment exclusionary rule, Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961).

Fifth Amendment right to just compensation for seizing private property, Chicago, B & Q RR v. Chicago, 166 U.S. 226 (1897).

Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination, Malloy v. Hogan, 378 U.S. 1 (1964).

Fifth Amendment double jeopardy clause, Benton v. Maryland, 395 U.S. 784 (1969).

Sixth Amendment right to counsel: Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45 (1932). The “Scottsboro Boys” case.

Sixth Amendment right to a public trial, In Re Oliver, 333 U.S. 257 (1948).

Sixth Amendment counsel for indigent defendants, Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963).

Sixth Amendment right to confront witnesses against you, Pointer v. Texas, 380 U.S. 400 (1965).

Sixth Amendment right to a speedy trial, Klopfer v. North Carolina, 386 U.S. 213 (1967).

Sixth Amendment right to compulsory process, Washington v. Texas, 388 U.S. 14 (1967).

Sixth Amendment right to a jury trial, Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145 (1968).

Sixth Amendment right to an impartial jury, Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145 (1968).

Eighth Amendment right against cruel and unusual punishment, Robinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660 (1962).

*Highlighted sections indicate changes identified in other parts of the Constitution of the United States.

Legislative Branch

Article I

Signed in convention September 17, 1787. Ratified June 21, 1788. A portion of Article I, Section 2, was changed by the 14th Amendment; a portion of Section 9 was changed by the 16th Amendment; a portion of Section 3 was changed by the 17th Amendment; and a portion of Section 4 was changed by the 20th Amendment.

Section 1: Congress

All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and House of Representatives.

Section 2: The House of Representatives

The House of Representatives shall be composed of Members chosen every second Year by the People of the several States, and the Electors in each State shall have the Qualifications requisite for Electors of the most numerous Branch of the State Legislature.

No Person shall be a Representative who shall not have attained to the Age of twenty five Years, and been seven Years a Citizen of the United States, and who shall not, when elected, be an Inhabitant of that State in which he shall be chosen.

Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons. The actual Enumeration shall be made within three Years after the first Meeting of the Congress of the United States, and within every subsequent Term of ten Years, in such Manner as they shall by Law direct. The number of Representatives shall not exceed one for every thirty Thousand, but each State shall have at Least one Representative; and until such enumeration shall be made, the State of New Hampshire shall be entitled to chuse three, Massachusetts eight, Rhode-Island and Providence Plantations one, Connecticut five, New-York six, New Jersey four, Pennsylvania eight, Delaware one, Maryland six, Virginia ten, North Carolina five, South Carolina five, and Georgia three.

When vacancies happen in the Representation from any State, the Executive Authority thereof shall issue Writs of Election to fill such Vacancies.

The House of Representatives shall chuse their Speaker and other Officers; and shall have the sole Power of Impeachment.

Section 3: The Senate

The Senate of the United States shall be composed of two Senators from each State, chosen by the Legislature thereof, for six Years; and each Senator shall have one Vote.

Immediately after they shall be assembled in Consequence of the first Election, they shall be divided as equally as may be into three Classes. The Seats of the Senators of the first Class shall be vacated at the Expiration of the second Year, of the second Class at the Expiration of the fourth Year, and of the third Class at the Expiration of the sixth Year, so that one third may be chosen every second Year; and if Vacancies happen by Resignation, or otherwise, during the Recess of the Legislature of any State, the Executive thereof may make temporary Appointments until the next Meeting of the Legislature, which shall then fill such Vacancies.

No Person shall be a Senator who shall not have attained to the Age of thirty Years, and been nine Years a Citizen of the United States, and who shall not, when elected, be an Inhabitant of that State for which he shall be chosen.

The Vice President of the United States shall be President of the Senate, but shall have no Vote, unless they be equally divided.

The Senate shall chuse their other Officers, and also a President pro tempore, in the Absence of the Vice President, or when he shall exercise the Office of President of the United States.

The Senate shall have the sole Power to try all Impeachments. When sitting for that Purpose, they shall be on Oath or Affirmation. When the President of the United States is tried, the Chief Justice shall preside: And no Person shall be convicted without the Concurrence of two thirds of the Members present.

Judgment in Cases of Impeachment shall not extend further than to removal from Office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any Office of honor, Trust or Profit under the United States: but the Party convicted shall nevertheless be liable and subject to Indictment, Trial, Judgment and Punishment, according to Law.

Section 4: Elections

The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time by Law make or alter such Regulations, except as to the Places of chusing Senators.

The Congress shall assemble at least once in every Year, and such Meeting shall be on the first Monday in December, unless they shall by Law appoint a different Day.

Section 5: Powers and Duties of Congress

Each House shall be the Judge of the Elections, Returns and Qualifications of its own Members,and a Majority of each shall constitute a Quorum to do Business; but a smaller Number may adjourn from day to day, and may be authorized to compel the Attendance of absent Members, in such Manner, and under such Penalties as each House may provide.

Each House may determine the Rules of its Proceedings, punish its Members for disorderly Behaviour, and, with the Concurrence of two thirds, expel a Member.

Each House shall keep a Journal of its Proceedings, and from time to time publish the same, excepting such Parts as may in their Judgment require Secrecy; and the Yeas and Nays of the Members of either House on any question shall, at the Desire of one fifth of those Present, be entered on the Journal.

Neither House, during the Session of Congress, shall, without the Consent of the other, adjourn for more than three days, nor to any other Place than that in which the two Houses shall be sitting.

Section 6: Rights and Disabilities of Members

The Senators and Representatives shall receive a Compensation for their Services, to be ascertained by Law, and paid out of the Treasury of the United States. They shall in all Cases, except Treason, Felony and Breach of the Peace, be privileged from Arrest during their Attendance at the Session of their respective Houses, and in going to and returning from the same; and for any Speech or Debate in either House, they shall not be questioned in any other Place.

No Senator or Representative shall, during the Time for which he was elected, be appointed to any civil Office under the Authority of the United States, which shall have been created, or the Emoluments whereof shall have been encreased during such time; and no Person holding any Office under the United States, shall be a Member of either House during his Continuance in Office.

Section 7: Legislative Process

All Bills for raising Revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives; but the Senate may propose or concur with Amendments as on other Bills.

Every Bill which shall have passed the House of Representatives and the Senate, shall, before it become a Law, be presented to the President of the United States; If he approve he shall sign it, but if not he shall return it, with his Objections to that House in which it shall have originated, who shall enter the Objections at large on their Journal, and proceed to reconsider it. If after such Reconsideration two thirds of that House shall agree to pass the Bill, it shall be sent, together with the Objections, to the other House, by which it shall likewise be reconsidered, and if approved by two thirds of that House, it shall become a Law. But in all such Cases the Votes of both Houses shall be determined by Yeas and Nays, and the Names of the Persons voting for and against the Bill shall be entered on the Journal of each House respectively. If any Bill shall not be returned by the President within ten Days (Sundays excepted) after it shall have been presented to him, the Same shall be a Law, in like Manner as if he had signed it, unless the Congress by their Adjournment prevent its Return, in which Case it shall not be a Law.

Every Order, Resolution, or Vote to which the Concurrence of the Senate and House of Representatives may be necessary (except on a question of Adjournment) shall be presented to the President of the United States; and before the Same shall take Effect, shall be approved by him, or being disapproved by him, shall be repassed by two thirds of the Senate and House of Representatives, according to the Rules and Limitations prescribed in the Case of a Bill.

Section 8: Powers of Congress

The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States; but all Duties, Imposts and Excises shall be uniform throughout the United States;

To borrow Money on the credit of the United States;

To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes;

To establish a uniform Rule of Naturalization, and uniform Laws on the subject of Bankruptcies throughout the United States;

To coin Money, regulate the Value thereof, and of foreign Coin, and fix the Standard of Weights and Measures;

To provide for the Punishment of counterfeiting the Securities and current Coin of the United States;

To establish Post Offices and post Roads;

To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries;

To constitute Tribunals inferior to the supreme Court;

To define and punish Piracies and Felonies committed on the high Seas, and Offenses against the Law of Nations;

To declare War, grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal, and make Rules concerning Captures on Land and Water;

To raise and support Armies, but no Appropriation of Money to that Use shall be for a longer Term than two Years;

To provide and maintain a Navy;

To make Rules for the Government and Regulation of the land and naval Forces;

To provide for calling forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions;

To provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining, the Militia, and for governing such Part of them as may be employed in the Service of the United States, reserving to the States respectively, the Appointment of the Officers, and the Authority of training the Militia according to the discipline prescribed by Congress;

To exercise exclusive Legislation in all Cases whatsoever, over such District (not exceeding ten Miles square) as may, by Cession of particular States, and the Acceptance of Congress, become the Seat of the Government of the United States, and to exercise like Authority over all Places purchased by the Consent of the Legislature of the State in which the Same shall be, for the Erection of Forts, Magazines, Arsenals, dock-Yards and other needful Buildings;-And

To make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof.

Section 9: Powers Denied Congress

The Migration or Importation of such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit, shall not be prohibited by the Congress prior to the Year one thousand eight hundred and eight, but a Tax or duty may be imposed on such Importation, not exceeding ten dollars for each Person.

The Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it.

No Bill of Attainder or ex post facto Law shall be passed.

No Capitation, or other direct, Tax shall be laid, unless in Proportion to the Census or Enumeration herein before directed to be taken.

No Tax or Duty shall be laid on Articles exported from any State.

No Preference shall be given by any Regulation of Commerce or Revenue to the Ports of one State over those of another: nor shall Vessels bound to, or from, one State, be obliged to enter, clear, or pay Duties in another.

No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law; and a regular Statement and Account of the Receipts and Expenditures of all public Money shall be published from time to time.

No Title of Nobility shall be granted by the United States: And no Person holding any Office of Profit or Trust under them, shall, without the Consent of the Congress, accept of any present, Emolument, Office, or Title, of any kind whatever, from any King, Prince, or foreign State.

Section 10: Powers Denied to the States

No State shall enter into any Treaty, Alliance, or Confederation; grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal; coin Money; emit Bills of Credit; make any Thing but gold and silver Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts; pass any Bill of Attainder, ex post facto Law, or Law impairing the Obligation of Contracts, or grant any Title of Nobility.

No State shall, without the Consent of the Congress, lay any Imposts or Duties on Imports or Exports, except what may be absolutely necessary for executing it's inspection Laws: and the net Produce of all Duties and Imposts, laid by any State on Imports or Exports, shall be for the Use of the Treasury of the United States; and all such Laws shall be subject to the Revision and Controul of the Congress.

No State shall, without the Consent of Congress, lay any Duty of Tonnage, keep Troops, or Ships of War in time of Peace, enter into any Agreement or Compact with another State, or with a foreign Power, or engage in War, unless actually invaded, or in such imminent Danger as will not admit of delay.

INTRODUCTION TO ARTICLE I

The Constitution first vests all federal legislative powers in a representative bicameral Congress. These legislative bodies must work together to draft and pass new laws and regulations.[85] Central to the social compact, this lawmaking institution forms the foundation of the federal government and allows the people’s representatives to act together for the common good. Article I, §I establishes several fundamental features of the Congress and creates the basis for the separation of powers between the executive and judicial branches.

ANALYSIS OF ARTICLE I

1. Bicameralism

The Framers of the Constitution of 1789 created a powerful national legislature to represent both the People and the States. Yet they also feared its awesome power and therefore determined to limit that power in order to protect individual liberty. The Vesting Clause defined as, "[t]he clause in the U.S. Constitution vesting the executive power in the President of the United States. U.S. Const. art. II, § 1,"[87] embodies two strategies for limiting Congress’s power. One strategy was to condition legislation upon the agreement of two differently constituted Chambers.[88] With smaller districts and short terms, the House of Representatives was expected to be responsive to "We the People." But hasty popular measures could be ameliorated or killed in the Senate, whose members served for longer terms and were selected by the state legislatures until enactment of the Seventeenth Amendment.

For the Framers, lawmaking by a representative bicameral Congress would serve a number of purposes. First, laws made by the people’s representatives would have legitimacy derived from the consent of the people. Second, by requiring members of Congress to deliberate and to compromise, the difficult process of lawmaking would promote laws aimed at the general good and equally applicable to all people. Third, laws made by a collective legislature would be more likely to avoid the dangers of small factions and special interests. Collective lawmaking would not be perfect, but, along with other Constitutional safeguards, would minimize the dangers of oppressive legislation. Therefore, these features reinforce why “all legislative powers herein granted” are vested in Congress and provided the framework for the concept of bicameralism. Bicameralism is defined by Black's Law as "[a] system of government with two legislative or parliamentary chambers. Both chambers must pass a bill before it can be presented to the executive and enacted into law."[89]

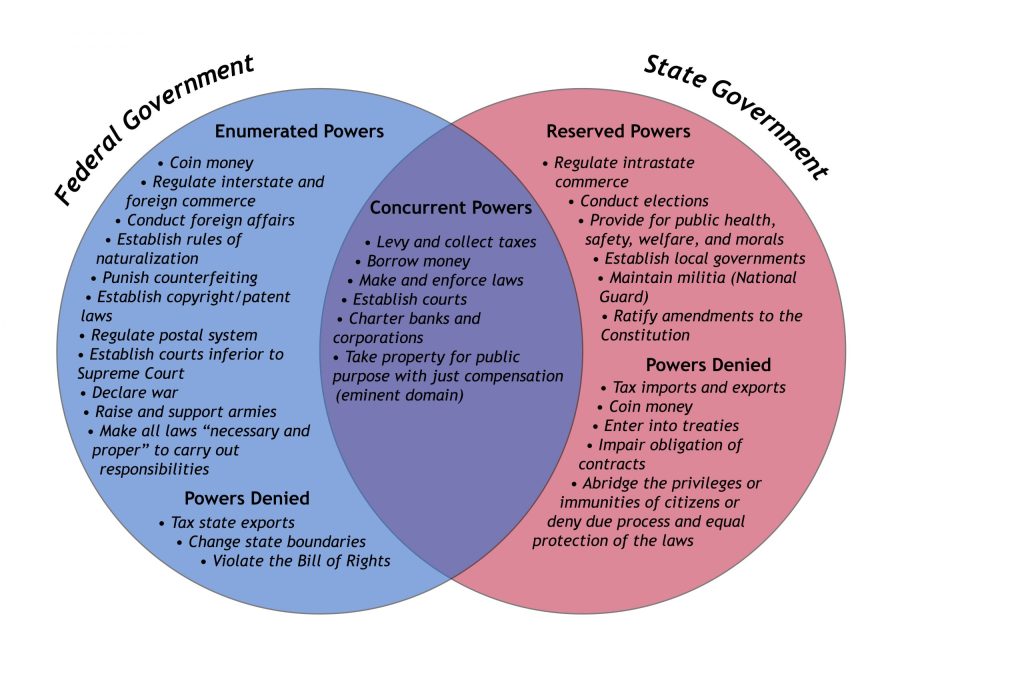

Powers Sharing - Differentiating Enumerated, Concurrent, and Reserved Powers[90]

The centrality of representative, legislative power suggests Constitutional limits on the delegation of legislative power to the Executive, which lacks the collective multi-member representation necessary for lawmaking.

2. Limited and Enumerated Powers

As a more explicit limitation, the Constitution vests Congress only with those legislative powers that are “herein granted.” Unlike state legislatures that enjoy plenary authority, Congress has authority only over the subject matter specified in the Constitution, particularly in Article I, §8. Early Presidents and Congresses knew intimately the limited jurisdiction of the federal government. They assumed no federal power to fund internal improvements, for example. Also, they debated what powers might be implied by the grant of the enumerated powers.

A significant early debate concerned whether Congress could create a Bank of the United States. James Madison and Thomas Jefferson argued against such a power, but President Washington ultimately supported Alexander Hamilton’s plan for the Bank. Although the Framers had rejected bank incorporation as an enumerated power, Washington still freely offered this support. The Supreme Court of the United States upheld the constitutionality of the Bank and recognized that the enumerated powers included some implied ones in McCulloch v. Maryland (1819).[91] Thus, the “necessary and proper" phrase in the last paragraph of §8 became known as the "elastic clause," giving Congress the authority to use powers not explicit in the Constitution, such as the creation of an Internal Revenue Service to collect taxes.[92]

3. Voting

Federal Government Voting[93]

Of course, not all of the people were eligible to vote at the time of ratification. Article I, §2 made the qualifications for voting in the United States House of Representatives (hereinafter U.S. House or House) elections the same as those for voting in the larger branch of the state legislature. That effectively excluded women, as well as many free African Americans and Native Americans. It also excluded some white men, who were barred from voting by property ownership requirements that were the norm in 1787.[94]

Some Framers favored making property ownership a qualification for voting in U.S. House elections, but Ben Franklin reminded them that many everyday individuals non-homeowners joined the fight for independence.[95] A uniform suffrage requirement was ultimately rejected, due to fears that it would lead some states to reject the Constitution altogether. The compromise - tying the qualifications for voting in U.S. House elections to the qualifications for voting in state legislative elections—allowed roughly two-thirds of white men - but very few others - to vote.[96]

Nevertheless, these direct elections were a significant milestone in the development of democracy. Many more people were eligible to vote in U.S. House elections than was the case under English law. In the ensuing decades, states moved rapidly toward universal suffrage for white men. The Fifteenth Amendment, adopted in 1870, prohibited denial of the vote on account of race. However, in practice, African-Americans were denied the right to vote in southern states for much of the twentieth century. Primarily white women gained a Constitutional right to vote with the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920.[97]

For most of American history, the apportionment of a particular State's representation in its legislature was determined by the State. This resulted in districts that heavily favored rural voters over urban voters.[98] For example, in California, 40% of the population lived in Los Angeles County, but under California's constitution that county was entitled to just one of forty state senators.[99] In 1962 the Supreme Court revolutionized representation in state legislatures with Baker v. Carr.[100] Two years later, in Reynolds v. Sims (1964), the Court proclaimed the doctrine of "one person, one vote," decreeing roughly equal-sized legislative districts.[101] By 1968, ninety-three of ninety-nine State legislative chambers had their lines redrawn to comply with the Supreme Court's ruling.[102]

Executive Branch

Article II

*Highlighted sections indicate changes identified in other parts of the Constitution of the United States.

Signed in convention September 17, 1787. Ratified June 21, 1788. Portions of Article II, Section 1, were changed by the 12th Amendment and the 25th Amendment

Section 1

The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.

He shall hold his Office during the Term of four Years, and, together with the Vice President, chosen for the same Term, be elected, as follows:

Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress: but no Senator or Representative, or Person holding an Office of Trust or Profit under the United States, shall be appointed an Elector.

The Electors shall meet in their respective States, and vote by Ballot for two Persons, of whom one at least shall not be an Inhabitant of the same State with themselves. And they shall make a List of all the Persons voted for, and of the Number of Votes for each; which List they shall sign and certify, and transmit sealed to the Seat of the Government of the United States, directed to the President of the Senate. The President of the Senate shall, in the Presence of the Senate and House of Representatives, open all the Certificates, and the Votes shall then be counted. The Person having the greatest Number of Votes shall be the President, if such Number be a Majority of the whole Number of Electors appointed; and if there be more than one who have such Majority, and have an equal Number of Votes, then the House of Representatives shall immediately chuse by Ballot one of them for President; and if no Person have a Majority, then from the five highest on the List the said House shall in like Manner chuse the President. But in chusing the President, the Votes shall be taken by States, the Representation from each State having one Vote; A quorum for this Purpose shall consist of a Member or Members from two thirds of the States, and a Majority of all the States shall be necessary to a Choice. In every Case, after the Choice of the President, the Person having the greatest Number of Votes of the Electors shall be the Vice President. But if there should remain two or more who have equal Votes, the Senate shall chuse from them by Ballot the Vice President.

The Congress may determine the Time of chusing the Electors, and the Day on which they shall give their Votes; which Day shall be the same throughout the United States.

No Person except a natural born Citizen, or a Citizen of the United States, at the time of the Adoption of this Constitution, shall be eligible to the Office of President; neither shall any person be eligible to that Office who shall not have attained to the Age of thirty five Years, and been fourteen Years a Resident within the United States.

In Case of the Removal of the President from Office, or of his Death, Resignation, or Inability to discharge the Powers and Duties of the said Office, the Same shall devolve on the Vice President, and the Congress may by Law provide for the Case of Removal, Death, Resignation or Inability, both of the President and Vice President, declaring what Officer shall then act as President, and such Officer shall act accordingly, until the Disability be removed, or a President shall be elected.

The President shall, at stated Times, receive for his Services, a Compensation, which shall neither be increased nor diminished during the Period for which he shall have been elected, and he shall not receive within that Period any other Emolument from the United States, or any of them.

Before he enter on the Execution of his Office, he shall take the following Oath or Affirmation:--"I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully execute the Office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my Ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States."

Section 2

The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States; he may require the Opinion, in writing, of the principal Officer in each of the executive Departments, upon any Subject relating to the Duties of their respective Offices, and he shall have Power to grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offenses against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment.

He shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two thirds of the Senators present concur; and he shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States, whose Appointments are not herein otherwise provided for, and which shall be established by Law: but the Congress may by Law vest the Appointment of such inferior Officers, as they think proper, in the President alone, in the Courts of Law, or in the Heads of Departments.

The President shall have Power to fill up all Vacancies that may happen during the Recess of the Senate, by granting Commissions which shall expire at the End of their next Session.

Section 3

He shall from time to time give to the Congress Information of the State of the Union, and recommend to their Consideration such Measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient; he may, on extraordinary Occasions, convene both Houses, or either of them, and in Case of Disagreement between them, with Respect to the Time of Adjournment, he may adjourn them to such Time as he shall think proper; he shall receive Ambassadors and other public Ministers; he shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed, and shall Commission all the Officers of the United States.

Section 4

The President, Vice President and all civil Officers of the United States, shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.

INTRODUCTION TO ARTICLE II

The Constitution next vests all federal executive/executive powers in a President. The Executive Office of the President (EOP) was created in 1939 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.[103] The EOP consists of many agencies which provide support for the huge presidential task of making crucial decisions for the United States of America.[104] Black's Law Dictionary defines "executive" as "The branch of government responsible for effecting and enforcing laws; the person or persons who constitute this branch."[105] This article refers to the office of the President, the Vice-President, independent federal agencies, including, but not limited to the "Department of Defense and the Environmental Protection Agency, the Social Security Administration and the Securities and Exchange Commission."[106] Although it appears to be limited with the president in head, the executive branch employs more than 4 million people.[107]

These individuals report to the cabinet or one of the following:

- Council of Economic Advisers

- Council on Environmental Quality

- Domestic Policy Council

- Gender Policy Council

- National Economic Council

- National Security Council

- Climate Policy Office

- Office of the Intellectual Property Enforcement Coordinator

- Office of Intergovernmental Affairs

- Office of Management and Budget

- Office of National Drug Control Policy

- Office of Public Engagement

- Office of Science and Technology Policy

- Office of the National Cyber Director

- Office of the United States Trade Representative

- Presidential Personnel Office and

- National Space Council.

"Because the president is elected, not appointed or born into the office like British royalty,"[108] history has shown us two divergent views of the Office of the President: the strong president or the weak president.

"One view, the "strong president" view, favored by presidents such as Theodore Roosevelt essentially held that presidents may do anything not specifically prohibited by the Constitution. The other view, "weak president" view, favored by presidents such as William Howard Taft, held that presidents may only exercise powers specifically granted by the Constitution or delegated to the president by Congress under one of its enumerated powers."[109]

President's Park also known as The United States White House - Executive Office of The President[110]

President's Park also known as The United States White House - Executive Office of The President[110]

To view the full list of United States Presidents visit the White House website.

ANALYSIS OF ARTICLE II

Section 1

John Adams, writing to his wife Abigail while Vice-President as well as considering the possibility of succeeding George Washington as President, noted “I am weary of the game, yet I don’t know how I could live out of it. I don’t love slight, neglect, contempt, disgrace, nor insult, more than others."[111]

Abigail Adams - American First Lady, Abigail Adams, oil on canvas by Gilbert Stuart, 1800–15; in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Gift of Mrs. Robert Homans, 1954.7.2[112]

Article II, §1 begins: “The executive power shall be vested in a President of the United States.” At a minimum, this Vesting Clause establishes an executive office to be occupied by an individual. At the founding, the creation of a separate executive was hardly obvious. The Articles of Confederation created no separate executive; duties that we associate with the executive were handled first by congressional committees, then by “Secretaries” or “Boards” under congressional direction. Nor was it self-evident that one individual would stand at the apex of the executive. Several states had plural executives (executive committees) and the notion of a plural executive had its backers at the Philadelphia Convention.

Few could disagree that the Vesting Clause establishes a unitary executive in the sense that it creates a single executive President. Throughout America's constitutional history, some politicians, judges, and scholars have argued that this minimal sense exhausts the content of the Clause.[113] Others have argued that the Clause does more and actually grants the President “the executive power.” In recent years, advocates of this latter view have identified their position with the label “Unitary Executive."[114] But this label is a bit misleading, for we would do well to remember that the idea that the Constitution establishes a unitary executive is perhaps universally shared, at least in the minimalist sense outlined above.

The Court has, from time to time, endorsed the idea that the Vesting Clause vests powers independent of the rest of Article II. In a case involving presidential dismissal of a postmaster, Myers v. United States (1926), the Court claimed that the Vesting Clause granted authority to execute the law and to remove executive officials.[115] In a decision from the late nineteenth century, In re Neagle (1890), the Court upheld the authority of the President to assign a federal marshal to protect a Supreme Court Justice who was threatened by a disgruntled litigant, despite the absence of any statute granting that authority.[116] In U.S. v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp. (1936), the Court famously announced that the President was the “sole organ of the nation in its external relations.”[117] In the 21st century, the Court observed in American Insurance Ass'n v. Garamendi (2003) that the “historical gloss” on the executive power conferred upon the President the vast share of foreign affairs powers.[118]

Under the umbrella of the Executive Branch is the administrative state. This is where the real day-to-day work of government occurs. Agencies that exist in the Executive Branch include the Department of Justice, the Department of Homeland Security, the State Department, the Defense Department, the Federal Trade Commission, the Federal Communications Commission, the Department of Education, the Department of Commerce, the Department of Labor, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the Office of Management and Budget, the Department of Treasury and Internal Revenue Service, the Occupational Health and Safety Administration, the Small Business Administration and the Environmental Protection Agency, among others. They are often known by their acronyms, such as DOJ, FTC, FCC, FEMA, IRS, OSHA, SBA and EPA. In the 1960s and its aftermath, a slew of new regulatory laws sought to address the excesses of economic growth, protecting clean air and water, ensuring worker safety, and policing auto and consumer product safety.

The Supreme Court, in Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc. (1984), ruled that courts will defer to expert agencies when they interpret a law with ambiguous wording.[119] Judges will not second-guess that approach if the agency has made a reasonable choice, and if Congress has not spoken directly to the precise issue at question.[120] This is known as the "Chevron Deference." The Supreme Court has applied it over 100 times creating the basis of thousands of legal decisions (or nondecisions) within the federal courts.[121]

However, in 2024 the Court, in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, ended the 40-year old precedent in Chevron in a 6-2 decision written by Chief Justice Roberts.[122] Instead of deferring to the expertise of agencies on how to interpret ambiguous language in laws pertaining to their work, federal judges now have the power to decide what a law means for themselves. Justice Elena Kagan, in dissent, remarked, "In one fell swoop, the majority today gives itself exclusive power over every open issue--no matter how expertise-driven or policy-laden--involving the meaning of regulatory law...As if it did not have enough on its plate, the majority turns itself into the country's administrative czar."[123]

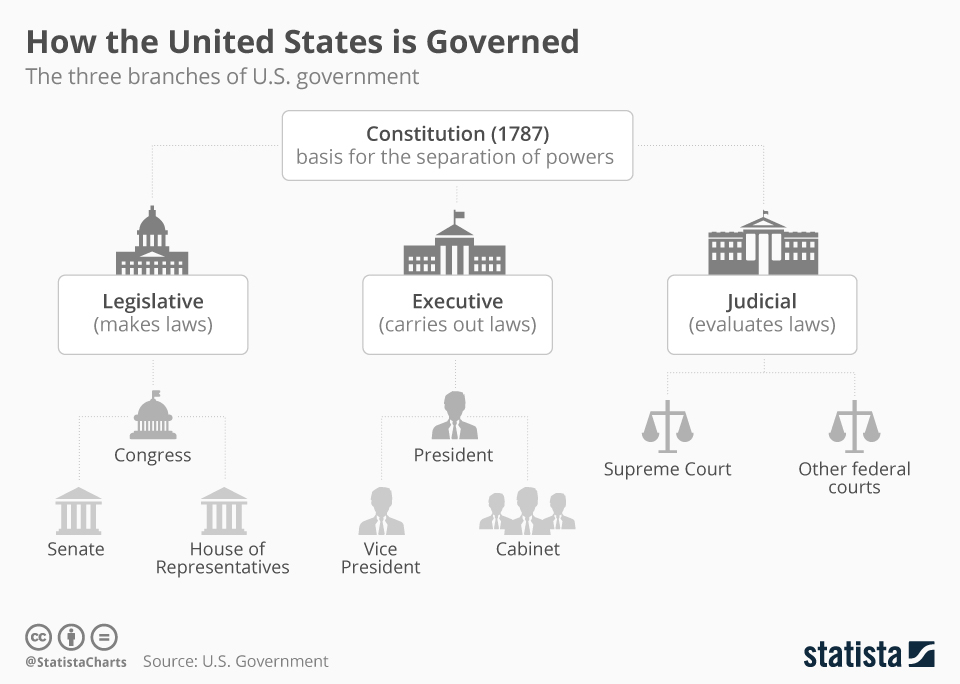

A significant case which addresses legislative power, executive power, and judicial power and their relationship to one another is Trump v. Mazars USA, LLP (2020). The Supreme Court of the United States addresses the concept of separation of powers when they held Congressional subpoenas which include Presidential information "implicate special concerns regarding the separation of powers."[124] As a result, the case was remanded to the lower courts to account for these "special concerns of separation of powers."[125] Black's defines separation of powers as "The division of governmental authority into three branches of government — legislative, executive, and judicial — each with specified duties on which neither of the other branches can encroach."[126]

Separation of Powers[127]

Separation of powers has its foundation in three separate constitutional provisions as listed below:

Article I, Section. 1:

All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and House of Representatives.

Article II, Section. 1:

The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.

Article III, Section. 1:

The judicial Power of the United States shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish.[128]

Although the three constitutional sections listed above provides the foundation for the separation of powers doctrine, separation of powers is not literally stated in the United States Constitution. James Madison believed this doctrine should be explicit within our document; however, other members of Congress felt the three sections above supported an implicit understanding of the Constitution and any additional verbiage would equal repetitive language.[129] Ultimately, separation of power meets two goals:

- "Prevents concentration of power (seen as the root of tyranny)"[130] and

- "provides each branch with weapons to fight off encroachment by the other two branches."[131]

Additionally, separation of power was reinforced through the checks and balances doctrine. Checks and balances defined as "The theory of governmental power and functions whereby each branch of government has the ability to counter the actions of any other branch, so that no single branch can control the entire government."[132] Finally, checks and balances work to balance the control and responsibility found in the first section of Articles I (Legislative), II (Executive), and III (Judicial) creating the separation of powers.

Another significant case in this area of executive power was decided by the Supreme Court in West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency (2022). The Court, by a 6-3 vote in a Roberts' majority opinion blocked many of the agency's potential efforts to curb carbon emissions from facilities that burn coal and other fossil fuels.[133] For the first time, the Court articulated a new "major questions doctrine," one that limited the power of agencies to act when a matter was really important.[134] Due to the "economic and political significance" of the regulation, Congress must give explicit authority or the agency cannot act.[135] The decision threatens any efforts by the EPA or other agencies to address the issue of climate change through regulation.[136]

The Constitution provides, in the second paragraph of Article II, §2, that “the President shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate to make Treaties, provided two thirds of the Senators present concur.”

ANALYSIS OF ARTICLE II

Section 2

Thus, treaty making is a power shared between the President and the Senate. In general, the weight of practice was to confine the Senate’s authority to that of disapproval or approval, with approval including the power to attach conditions or reservations to the treaty.

For instance, the authority to negotiate treaties was assigned to the President alone as part of a general authority to control diplomatic communications. Thus, since the early Republic, the Clause has not been interpreted to give the Senate a constitutionally mandated role in advising the President before the conclusion of the treaty.[137]

ANALYSIS OF ARTICLE II

Section 3

The remainder of Paragraphs 2 and 3 of Article II deals with the subject of official appointments. With regard to diplomatic officials, judges and other officers of the United States, Article II lays out four modes of appointment. The default option allows appointment following nomination by the President and the Senate’s “advice and consent.” With regard to “inferior officers,” Congress may, within its discretion, vest their appointment “in the President alone, in the courts of law, or in the heads of departments.” The Supreme Court has not drawn a bright line distinguishing between inferior officers who might be appointed within the executive branch and inferior officers Congress may allow courts to appoint, provided only that, for judicial appointees, there be no “‘incongruity’ between the functions normally performed by the courts and the performance of their duty to appoint."[138]

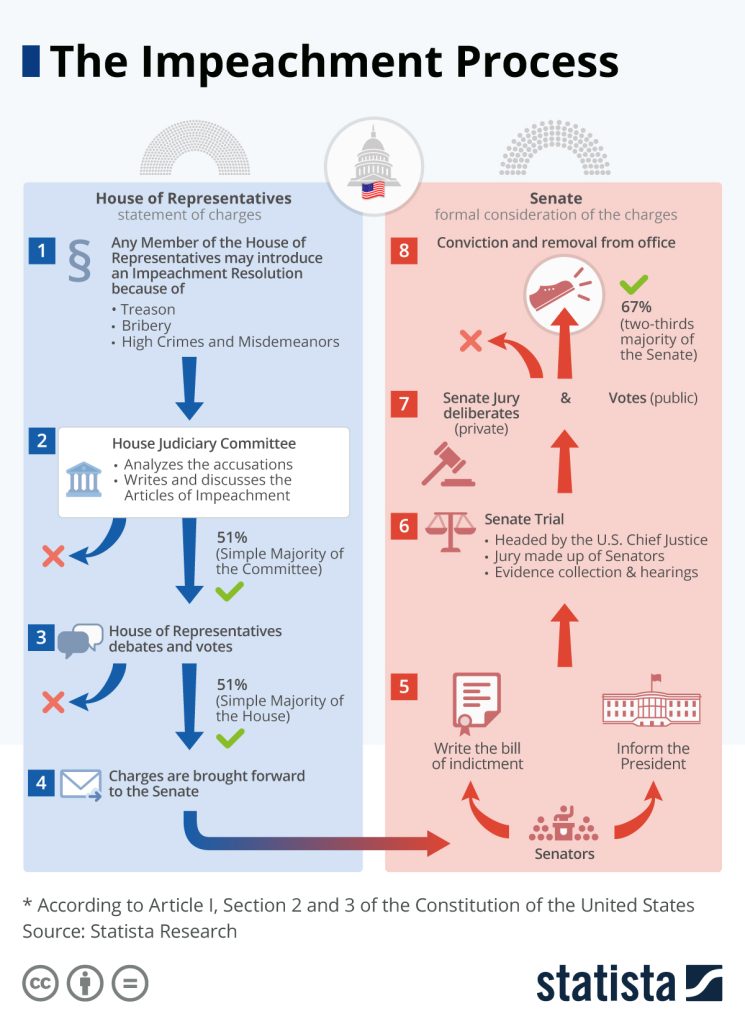

The final section of Article II, which generally describes the executive branch, specifies that the “President, Vice President and all civil Officers of the United States” shall be removed from office if convicted in an impeachment trial of “Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.” Two clauses in Article I lay out the role of the House and the Senate in impeachments and in trials of impeachment. Impeachment is defined as "{a} quasi-judicial process by which a legislative chamber calls for the removal from office of a public official, or disqualification from future officeholding of a former officeholder, accomplished by presenting a written charge of the official's alleged misconduct; esp., the initiation of a proceeding in the U.S. House of Representatives against a federal official, such as the President or a judge."[139] In practice, impeachments by the House have been rare, and convictions after a trial by the Senate even less common. Three Presidents, one Senator, one cabinet officer, and fifteen judges have been impeached, and of those only eight judges have been convicted and removed from office.[140] To see all Senate Impeachment trials, visit the Senate website. Finally, below is an infographic which explains The Impeachment Process.[141]

You will find more infographics at Statista.

You will find more infographics at Statista.

ANALYSIS of Article II

Section 4

This sparse history has given Congress relatively few opportunities to flesh out the bare bones of the Constitutional text. The Impeachment Clause was included in the Constitution in order to create another check against abuses by government officials and to give Congress the ability to remove from power an unfit officer who might otherwise be doing damage to the public good. Unsurprisingly, most “civil officers of the United States” who have found themselves damaged by scandal have preferred to resign, rather than endure an impeachment. The House and Senate have refused to act on impeachment charges against individuals who were not then holding a federal office. Early on, the Senate decided that members of Congress should be expelled by their individual chambers rather than be subjected to an impeachment trial. Presidents have acted quickly to remove problematic members of the executive branch. As a practical matter, judges and Presidents have been the primary targets of impeachment inquiries.