Chapter 4 – Amendment II: Balancing Federal, State, and Individual Rights

Amendment II

Richard J. Forst and Tauya R. Forst

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

4.1 Identify the unfamiliar terms of the Second Amendment.

4.2 Describe the two parts of the Second Amendment.

4.3 Summarize the right defined by the Second Amendment.

4.4 Analyze the development of case law defining the rights defined by the Second Amendment.

4.5 Compare the rights of the Second Amendment through the federal, state, and individual position.

4.6 Explain the progression of the Second Amendment from its origin to its current position.

4.7 Describe the three interpretations of the Second Amendment.

KEY TERMS

| Commerce Clause | National Firearms Act of 1934 |

| Free State | Operative Clause |

| Grand Jury Indictment | Per Curiam |

| Infringe[d] | Prefatory Clause |

| Infringement | Presentment |

| Militia | Right to Bear Arms |

Amendment II

Passed by Congress September 25, 1789. Ratified December 15, 1791. The first 10 amendments form the Bill of Rights.

A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.

Getting Started

First, determine how many parts exist in the Second Amendment. This will require a literal reading of each part of the amendment. Once we determine the parts, we can understand the verbiage of the United States Constitution. The Second Amendment on its face elicits strong feelings which tend to silo those who disagree. Moreover, it is important to bring an open mind to this discussion as you study, learn and apply the varied factors which affect the Second Amendment.

Reenactment of a Musket Shooting *Picture taken by Tauya Forst – Savannah, Georgia

INTRODUCTION TO AMENDMENT II

Once we determine the parts of the Second Amendment, we can understand the verbiage of the United States Constitution. The Second Amendment on its face elicits strong feelings which tend to silo those who disagree. Moreover, it is important to bring an open mind to this discussion as you study, learn, and apply the varied factors which affect the Second Amendment.

Pictured above is a musket, the weapon used during the Civil War.[1] This weapon was contemplated during the debates surrounding the Second Amendment. This photograph was taken by the authors during a visit to a historical site in Savannah, Georgia. The man pictured produced a reenactment of the use and discharge of this musket for historical context as he explained the use of the weaponry. A musket takes one and one half minutes to load. “Early muskets were often handled by two persons and fired from a portable rest.”[2] One shot would kill a person immediately; however, due to the lack of training and inferior parts, soldiers took more than 20 shots to hit an individual.[3]

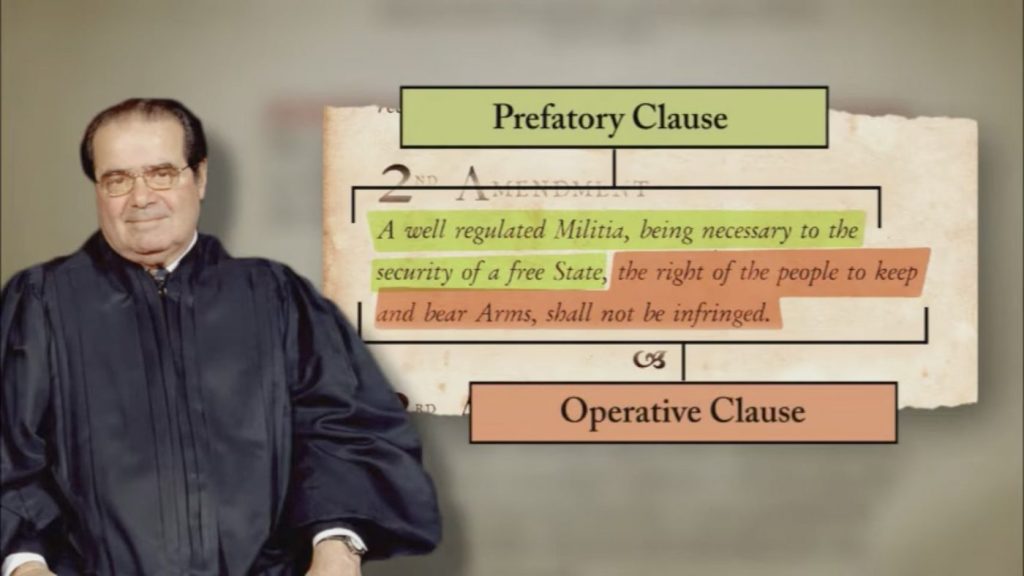

Justice Antonin Scalia with the Two Clauses of the Second Amendment – Prefatory and Operative Clause[4]

Debate regarding the Second Amendment centers around the prefatory clause and the intentions of the founding fathers.[5] Militia is the term to understand with regard to the Second Amendment. According to Black’s Law Dictionary, militia is defined as “[a] body of citizens armed and trained, [especially] by a state, for military service apart from the regular armed forces.”[6]

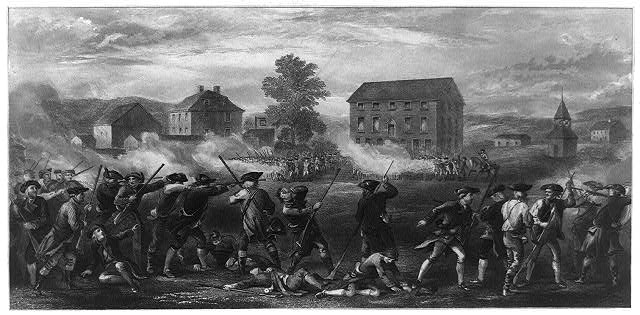

Battle of Lexington – A line of minutemen being fired upon by British troops during the Battle of Lexington in Massachusetts, April 19, 1775.[7]

Militia has been defined and interpreted two ways. It often refers to those individuals who are eligible to serve in an emergency situation, if need be. The other meaning includes those who are formally trained, equipped, organized, uniformed and prepared to be deployed. The second meaning refers to those who are enrolled in the National Guard. As explained in Black’s Law Dictionary, according to the United States “Constitution, [the government] recognizes a state’s right to form a ‘well-regulated militia’ but also grants Congress the power to activate, organize, and govern a federal militia” through Art. I, §8, cl. 15-16.[8]

Nevertheless, these individuals are excepted from the rule of presentment and/or the grand jury indictment. According to Black’s Law Dictionary defines presentment as “[a] formal written accusation returned by a grand jury on its own initiative, without a prosecutor’s previous indictment request.”[9] Equally important to note that currently, [p]resentments are obsolete in the federal courts.”[10] Additionally, a grand jury indictment is defined as “[t]he formal written accusation of a crime, made by a grand jury and presented to a court for prosecution against the accused person.”[11] The term indictment hails from the French root word enditer and indicates “an accusation found by an inquest of twelve or more upon their oath.”[12]

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

“By 1862, most Union soldiers were equipped with rifled muskets, and many carried the Model 1861. This meant that the average infantryman was far more lethal than in previous wars, with a highly accurate long-range weapon. Tactics and training lagged behind, however, and most infantrymen on both sides struggled to hit targets at range or utilize the weapon’s sights effectively. For the Confederacy, the Enfield Pattern 1853 represented the most readily available small arm, and was highly sought after. Because of Confederate manufacturing limitations, the Enfield made up the majority of their rifles carried by the infantry by war’s end. While almost identical in terms of range and accuracy as the Springfield Model 1861, most of the Enfields purchased by the Confederacy were made by contractors, and suffered from inferior parts and difficulties with interchangeability. Given the choice, many Confederate soldiers preferred the Springfield, but picked the Enfield over all other options.”[13]

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

THREE INTERPRETATIONS OF AMENDMENT II

“First, it can be argued that the Second Amendment consists of an opening justification phrase followed by a declarative clause. Under this interpretation, the opening phrase is essential to the main clause, and this interpretation would result in a protection of the right to bear arms if a person is serving in the militia.

Second, another possible interpretation views the first phrase as one nonexclusive example of one instance in which individuals have the right to bear arms. Using this interpretation, the Second Amendment would protect the individual right to bear arms for more reasons than just military purposes.

Third, yet another possible interpretation views the first clause as explanatory; that militia service is the reason that we allow people to keep and bear arms, but that other restrictions do not exist. Thus, the fact that the second part of the amendment guarantees the right to bear arms to “the people” means that all citizens can bear arms, not just those involved in the militia.”[15]

Of extreme importance and note: The Supreme Court of the United States explicitly denied an individual right to keep and bears arms in United States v. Cruikshank (1875).[16] Through Chief Justice Morrison Waite, the court held

“The right there specified is that of ‘bearing arms for a lawful purpose.’ This is not a right granted by the Constitution. Neither is it in any manner dependent upon that instrument for its existence. The second amendment declares that it shall not be infringed; but this, as has been seen, means no more than that it shall not be infringed by Congress.”[17]

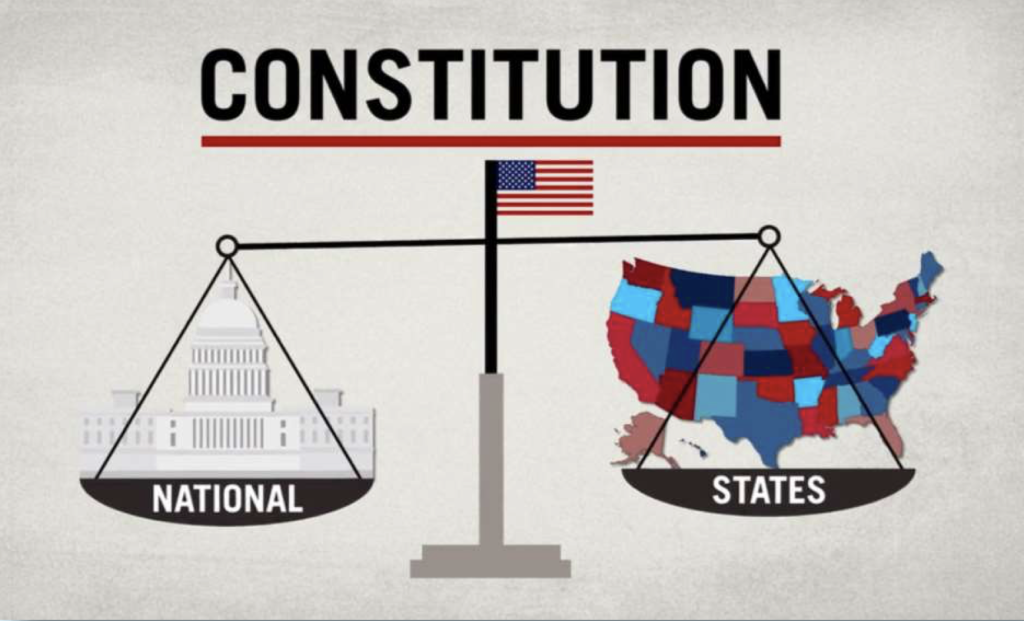

As a result of United States v. Cruikshank (1875) and Fryling’s possible explanations, the interpretation of the Second Amendment involves balancing federal, state, and individual rights – a familiar theme contained in the United States Constitution. In this way, it is important to read this chapter and review the included timeline to determine when the federal, state, and individual rights are in the forefront of the explanation. This balancing act requires all parties to regard the Second Amendment in a realistic framework. It is important to note that political viewpoints provided inappropriate interpretations of the Second Amendment as explained by then-National Rifle Association’s (NRA) President Karl T. Frederick.[18]

“I have never believed in the general practice of carrying weapons,” said then-NRA President Karl T. Frederick at a Congressional hearing over the National Firearms Act of 1934.[19] “I do not believe in the general promiscuous toting of guns. I think it should be sharply restricted and only under licenses.”[20] Mr. Frederick’s beliefs exemplify the historical differences in the understanding of the Second Amendment. At the time of the 1791 ratification of the Second Amendment, the Framers and the U.S. Congress exercised authority over the understanding of the Amendment. Recall, amendments are subject to change by the following legal actions: Congressional, State, and local acts, as well as Supreme Court cases. In these legal actions, federal, state, and ultimately individual rights are identified and acknowledged.

According to Harr, the stricter interpretation of the three listed above set a standard for states to either adopt and/or modify gun restrictions as their influence begins to unfold.[21] In the states’ rights debate, proponents note there is a need to protect and modify Art. I, §8, cl. 2, which speaks to the Commerce Clause of Congress. According to Black’s Law Dictionary, the Commerce Clause is in the “[United States Constitution Art. I, §8, cl. 3], which gives Congress the exclusive power to regulate commerce among the states, with foreign countries, and with Indian tribes.”[22] Additionally proponents frequently cite Art. I, §8, cl. 15 which speaks to the militia and reserving certain rights to the states. The Commerce Clause quoted below serves as the legal foundation for much of the federal government’s regulatory authority, but this section directly points to the connection of the militia.

“To provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining, the Militia, and for governing such Part of them as may be employed in the Service of the United States, reserving to the States respectively, the Appointment of the Officers, and the Authority of training the Militia according to the discipline prescribed by Congress;”[23]

Individual Rights[27]

Although the federal rights and states’ rights arguments exist, it is important to balance the third entity of rights – the individual rights. As stated previously, an individual rights’ interpretation guarantees the right to bear arms to all citizens. According to Black’s Law Dictionary, the right to bear arms is defined as “[t]he constitutional right of persons to own firearms.”[28] Unlike the states’, the individual rights’ proponents see the Second Amendment as primarily guaranteeing the right of the people, not the states.[29]

Additionally, proponents claim that the Framers of the United States Constitution intended for states’ rights to be subservient to individual rights. Unfortunately, Harr notes that the historical treatment of individual rights versus states’ rights interpretation shows the courts consistently supporting the states’ rights interpretation.[30] Finally, the Supreme Court has interpreted this Amendment in very few cases; however, this text will examine and analyze the important legal changes which support the evolution of the Second Amendment over the course of American history.

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT II

Two Clauses of the Second Amendment

a. Prefatory Clause (State’s rights) – Announces a purpose, but does not necessarily restrict operative clause. (A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State,

) In an effort to help understand this section, we will define security in this context.

b. Operative Clause (Individual rights) – Identifies that action to be taken or prohibited. (the right of the people to keep and bear Arms shall not be infringed

) To this end, infringe means “to encroach upon in a way that violates law or the rights of another.”[31]

Four Parts of the Second Amendment

Part I: A well regulated Militia

The Framers of the Bill of Rights, mainly James Madison, adapted the wording of the Amendment from nearly identical clauses from the original thirteen state constitutions.[32] During the Revolutionary War era, “militia” referred to groups of men who banded together to protect their communities, towns, and colonies.[33] Once the United States declared its independence from Great Britain in 1776, these groups of men banded together to protect states as well.

At that time, Americans widely held that governments used soldiers to oppress the people and thought the federal government should only be allowed to raise armies (with full-time, paid soldiers) when facing foreign adversaries.[34] For all other purposes, they believed the government should turn to part-time militias, or ordinary civilians using their own weapons. But as militias had proved insufficient against the British, the Constitutional Convention gave the new federal government the power to establish a standing army, even in peacetime as described in the Third Amendment.[35]

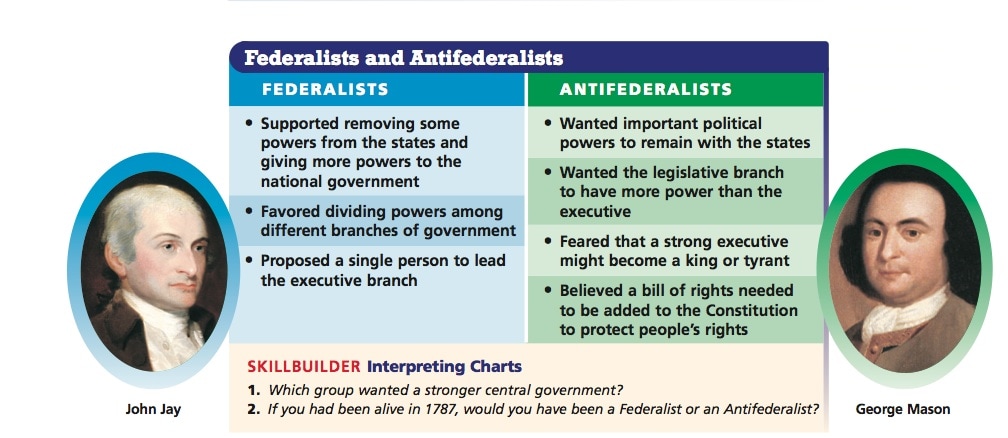

Difference between Federalists and Anti-federalists[36]

However, opponents of a strong central government (the “Anti-Federalists”) argued that this federal army deprived states of their ability to defend themselves against oppression. They feared that Congress might abuse its Constitutional power of “organizing, arming and disciplin[ing] the Militia” by failing to keep militiamen equipped with adequate arms.[37] Shortly after the U.S. Constitution was ratified by the States, Madison proposed the Second Amendment to empower state militias for protection. It established the principle, held by both Federalists and Anti-Federalists, that the government did not have the authority to disarm citizens.[38]

What is special about the Amendment is the inclusion of an opening clause – a preamble, if you will – that seems to set out its purpose. No similar clause is a part of any other Amendment as noted by Professor Sanford Levinson.[39]

Consider, for example, the Virginian George Mason who refused to sign the United States Constitution because of its lack of a Bill of Rights. He questioned, “Who are the Militia? They consist now of the whole people.”[40] Similarly, the “Federal Farmer,” a nom de plume for one of the most important Anti-Federalist opponents of the Constitution, referred to a “militia, when properly formed, [as] in fact the people themselves.”[41]

Part II: , being necessary to the security of a free state,

James Harrington, a renowned Anti-Federalist writer feared all future republicans (not the formal Republican Party – as it did not exist at the time, but those who believed in a republican form of government) and disdained a standing army, composed of professional soldiers. Harrington and his fellow republicans viewed a standing army as a threat to freedom, to be avoided at almost all costs. Thus, says Professor Edmund Morgan, “A militia is the only safe form of military power that a popular government can employ; and because it is composed of the armed yeomanry, it will prevail over the mercenary professionals who man the armies of neighboring monarchs.”[42]

Anti-Federalists were concerned that their own “free states” would be overrun by the central government’s standing army. According to Black’s Law Dictionary, free state as “[a] political community organized independently of all others.”[43] This phrase, set apart by commas at the beginning and end of the phrase, purports to explain the need for the protection of the Second Amendment.[44]

Part III: the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed.

The third phrase of the Second Amendment, again delineated by commas indicates a separate thought being conveyed from the others. The Amendment establishes a right, much like the rights established in the First Amendment. What is this right to keep and bear arms? Who has it? Are “the people” individuals, or are they members of a local state army, a “militia?” And do the members of the “militia” have the right to keep arms in their possession at all times? Are they able to only keep arms in their homes or while participating in militia activities?

As for the last phrase, does it mean there can be no regulations, restrictions, or limitations on the right? Or are some permissible?

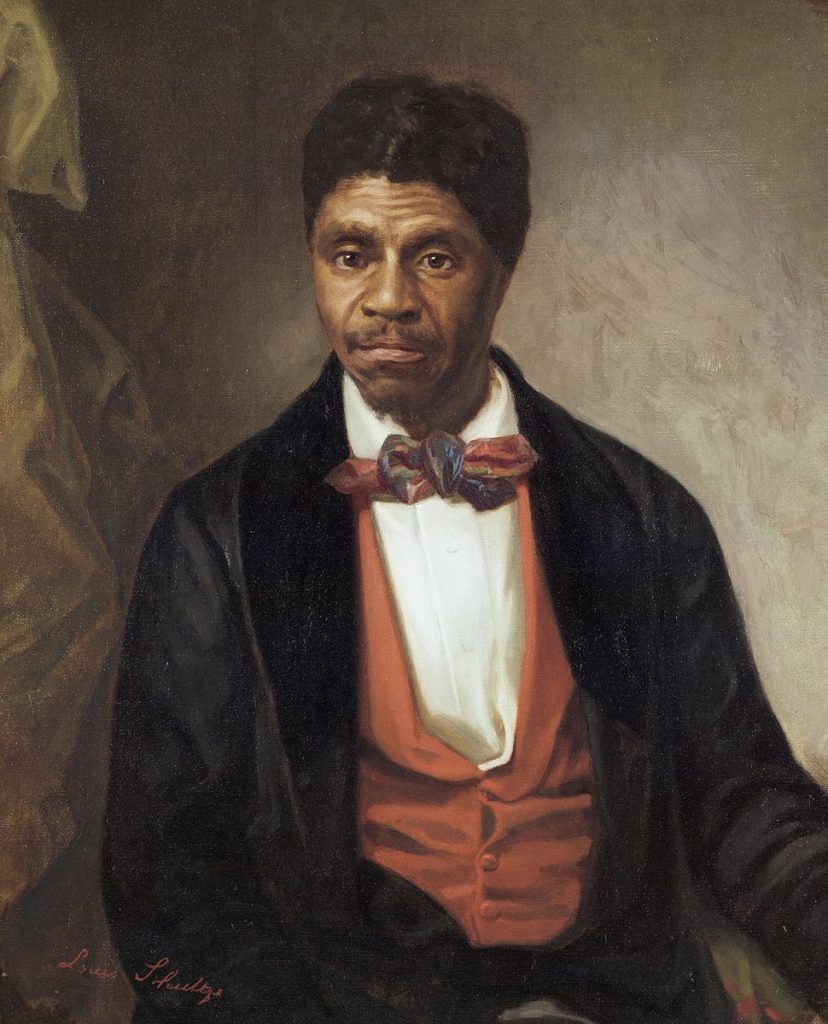

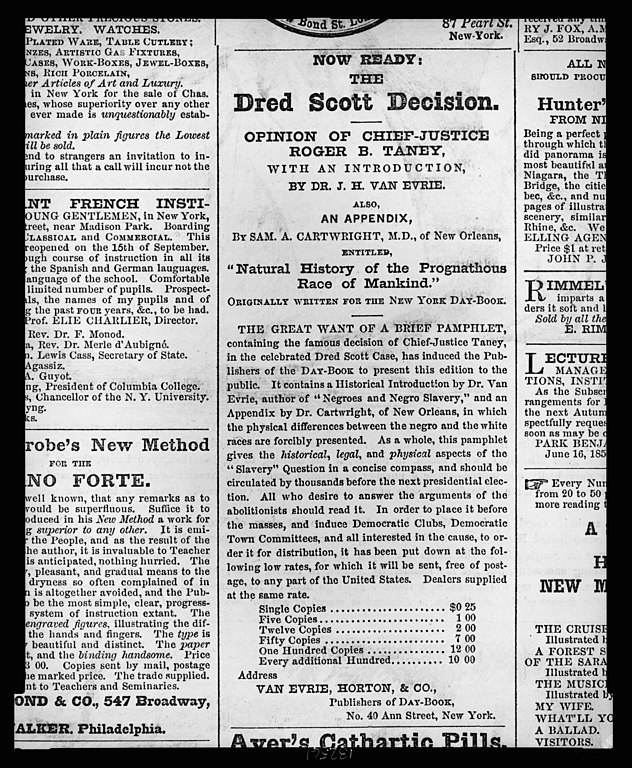

Dred Scott v Sandford, 60 U.S. 393 (1857)[45]

Cases

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

The strongest version of the Anti-Federalist argument held the individual right to bear arms to be a “privilege and immunity of United States citizenship” of membership in a liberty-enhancing political order. This individual right included keeping arms that could be taken up against tyranny wherever found, including the state government. Ironically, the principal citation supporting this argument is to Chief Justice Taney’s egregious opinion in the infamous Dred Scott (1857) decision where he suggested that an uncontroversial attribute of citizenship, in addition to the right to migrate from one state to another, was the right to possess arms.[46] The logic of Taney’s argument at this point seems to be that, because it was inconceivable that the Framers could have genuinely imagined blacks having the right to possess arms, it follows that they could not have envisioned them as being citizens, since citizenship entailed that right. Taney’s seeming recognition of a right to arms is heavily relied upon for opponents of gun control.[47]

a. the evolution of the Second Amendment

Part IV: Evolution of the Second Amendment – Balancing Federal, State and Individual Rights

Professor Laurence Tribe of Harvard Law School asserts that the history of the Second Amendment “indicate[s] that the central concern of [its] framers was to prevent such federal interferences with the state militia as would permit the establishment of a standing national army and the consequent destruction of local autonomy.”[48] The Second Amendment began with the ratification in 1791, however, several key cases created the foundation for the ratification. In the next section, note the key cases that provided the complete evolution of how the amendment progressed. Moreover, the Second Amendment leverages these cases to provide support to current arguments for and against the Second Amendment’s status today. A comprehensive approach to this analysis is included in the below, entitled Second Amendment Timeline.

Cases

In United States v. Miller (1939), the Court held unanimously that Congress could prohibit the possession of a sawed-off shotgun because that sort of weapon had no reasonable relation to the preservation or efficiency of a “well-regulated Militia.”[49]

Jack Miller of United States v. Miller, 307 U.S. 174 (1939)[50]

Miller, along with another robber, was charged with moving a sawed-off shotgun in interstate commerce in violation of the National Firearms Act of 1934. The National Firearms Act of 1934 (NFA) “…imposed a tax on the making and transfer of firearms defined by the Act, as well as a special (occupational) tax on persons and entities engaged in the business of importing, manufacturing, and dealing in NFA firearms. The law also required the registration of all NFA firearms with the Secretary of the Treasury.”[51] Among other things, Miller and a compatriot failed to register the shotgun, as required by the NFA. The court below dismissed the charge, accepting Miller’s argument that the Act violated the Second Amendment.

The arch-conservative Justice James McReynolds of the Supreme Court wrote the opinion. The Supreme Court reversed the District Court stating “the Second Amendment doesn’t guarantee the right to keep and bear a sawed-off shotgun.”[52] Interestingly, Justice McReynolds emphasized that there was no evidence showing that a sawed-off shotgun “at this time has some reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia.”[53] However, “[c]ertainly it is not within judicial notice that this weapon is any part of the ordinary military equipment or that its use could contribute to the common defense.”[54]

It is possible Miller could offer a tenable argument to show that he was keeping or bearing a weapon that clearly had a potential military use. Justice McReynolds went on to describe the purpose of the Second Amendment as “assur[ing] the continuation and render[ing] possible the effectiveness of [the militia].[55] He contrasted the militia with troops of a standing army, which the Constitution forbade the states to keep without the explicit consent of Congress.”[56] The sentiment of the time strongly disfavored standing armies; the common view was that adequate defense of country and laws could be secured through the Militia-civilians primarily, soldiers on occasion.

Associate Justice James Clark McReynolds delivered majority opinion in U.S. v. Miller (1939)[57]

“Justice McReynolds noted further that “the debates in the Convention, the history and legislation of Colonies and States, and the writings of approved commentators [all] [s]how plainly enough that the Militia comprised all males physically capable of acting in concert for the common defense.”[58]

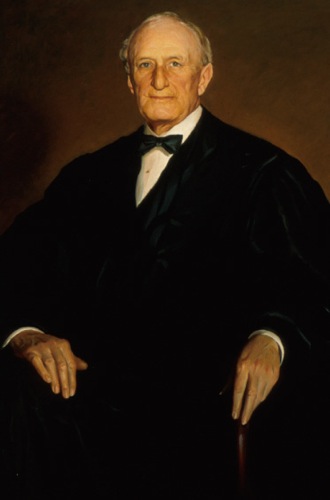

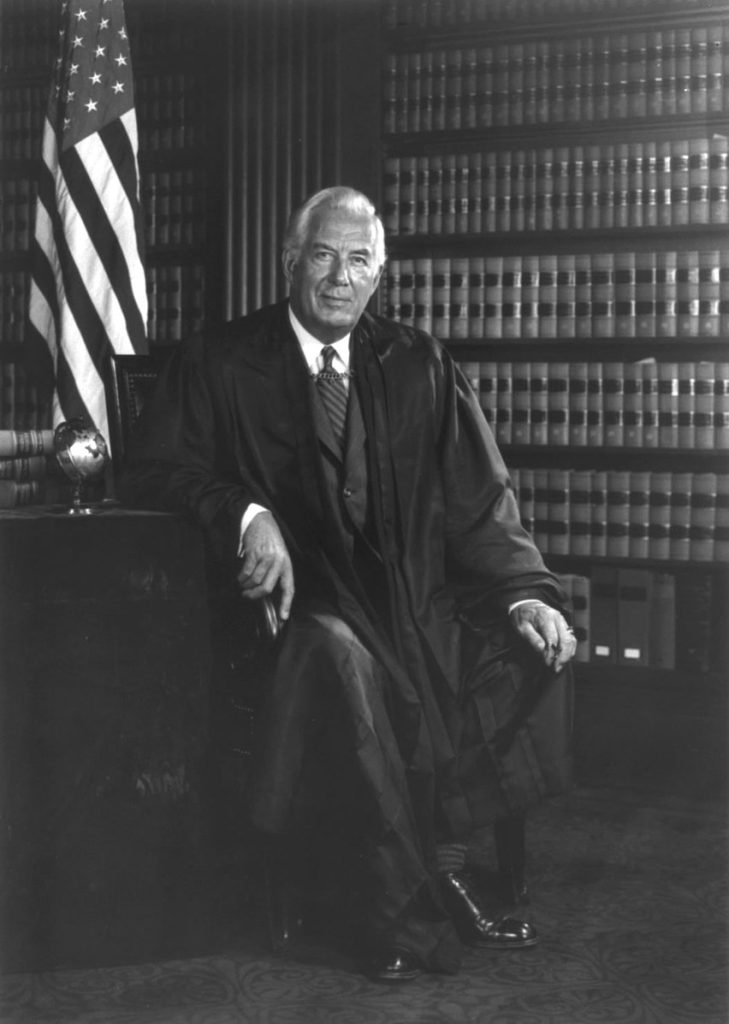

Additionally, Justice John Paul Stevens gave his first-hand historical context of Miller. Justice Stevens acknowledged “[w]hen I joined the Court in 1975, that holding [in Miller] was generally understood as limiting the scope of the Second Amendment to uses of arms that were related to military activities.[59] During the years when Warren Burger was Chief Justice, 1969 to 1986, Justice Stevens noted “no judge or justice expressed any doubt about the limited coverage of the amendment, and I cannot recall any judge suggesting that the amendment might place any limit on state authority to do anything.” [60] Five years after his retirement, during a 1991 appearance on the “MacNeil/Lehrer News Hour,” Burger himself remarked that the Second Amendment “has been the subject of one of the greatest pieces of fraud, I repeat the word ‘fraud,’ on the American public by special interest groups that I have ever seen in my lifetime.’”[61] To say that the Second Amendment is engulfed in controversy is a mere understatement. However, most justices agree the controversy leaves the American public clueless regarding the true Second Amendment evolution as the historical explanations culminate into political debates.[62]

Warren Burger, Chief Justice of the United States, 1969-1986[63]

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

Justice James Clark McReynolds, who wrote the Court’s unanimous opinion in U.S. v. Miller (1939), was known for his anti-Semitic and racist views. Justice William Howard Taft called him “selfish to the last degree” and “fuller of prejudice than any man I have ever known.”[64] McReynolds refused to speak to Justice Louis Brandeis, a Jew, for three years, to sit near him during Court ceremonies, or to sign any opinions written by him. He was also given to venting about “un-Americans” and “political subversives.”[65]

b. the current state of the Second Amendment

Cases

In Printz v. United States (1997), the Court held that certain interim provisions of the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act violated the Tenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.[66] The Court created the “anti-commandeering rule,” which provides that the federal government cannot “commandeer” local or state officials to implement and enforce federal regulations.[67] In this case, universal background checks on gun purchases. This was the first venture by the Supreme Court into Second Amendment territory since U.S. v. Miller (1939). The majority opinion, penned by Justice Antonin Scalia in a 5-4 decision, was a forerunner to the cases that followed.[68]

An Introduction to Constitutional Law » D.C. v. Heller with Dick Heller[69]

Another landmark case which addresses the Second Amendment is District of Columbia v. Heller (2008).[70] In a 5-4 decision, the Supreme Court held in Heller that a civilian has a right to keep a handgun in his home for purposes of self-defense. Justice Antonin Scalia, writing for the slim majority, challenged the constitutionality of a 32-year-old handgun ban in Washington, D.C., and found, “The handgun ban and the trigger-lock requirement (as applied to self-defense) violate[s] the Second Amendment.”[71] At the same time, the Court recognized the existence (and, later, fundamentality) of an individual right to keep and bear arms for private purposes like self-defense in the home, the Court also noted that this right, “[l]ike most rights, . . . [are] not unlimited.”[72]

Meet the Plaintiffs: McDonald v. Chicago, 561 U.S. 742 (2010)[73]

“Meet the plaintiffs: These four Chicago residents (from left), Adam Orlov, David and Colleen Lawson, and Otis McDonald, … sued to repeal the city’s ban on handgun possession.”[74]

As examples of constitutionally acceptable limitations, the Court noted prohibitions on carrying concealed weapons, on the possession of firearms by felons and the mentally ill, as well as laws forbidding carrying firearms in sensitive places such as schools and government buildings. Additionally, prohibitions existed which imposed conditions and qualifications on the commercial sale of arms – specifically identified by the majority opinion as permissible regulations.[75]

In McDonald v. Chicago (2010), the Supreme Court’s 5-4 landmark decision emphasized the fact that the Second Amendment applies to state and local governments, by incorporation through the Fourteenth Amendment.[76]

Thus, Justice Stevens stated that nothing in either the Heller or the McDonald majority opinion poses any obstacle to the adoption of such preventive measures as a ban on the sale of assault weapons or more complete background checks on purchasers of firearms.[77] Stevens further argues that the Court did not overrule Miller. Rather, the Court ruled that only weapons of a specific caliber were in the protected class deserving of Second Amendment protection. Machine guns and sawed-off shotguns might be helpful for self-defense, but they do not satisfy the “in common use” requirement.  Are Stun Guns Protected By Second Amendment? Supreme Court Suggests Yes[78]

Are Stun Guns Protected By Second Amendment? Supreme Court Suggests Yes[78]

The “in common use” requirement was tested in Caetano v. Massachusetts (2016), a per curiam opinion. The Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts upheld a Massachusetts law prohibiting the possession of stun guns after examining “whether a stun gun is the type of weapon contemplated by Congress in 1789 as being protected by the Second Amendment.”[79] SCOTUS ruled that “this is inconsistent with Heller’s clear statement that the Second Amendment “extends . . . to . . . arms . . . that were not in existence at the time of the founding,” reversing the Massachusetts high court.[80] In a concurring opinion, Justice Samuel Alito stated,

“[t]his reasoning defies our decision in Heller, which rejected as ‘bordering on the frivolous’ the argument ‘that only those arms in existence in the 18th century are protected by the Second Amendment.’ Also, the decision below does a grave disservice to vulnerable individuals like Caetano who must defend themselves because the State will not.”[81]

Thus, the Supreme Court extended the scope of weaponry protected by Heller to stun guns.[82]

Black’s Law Dictionary defines a per curiam opinion as “[(o]f an appellate judicial opinion) attributed to the entire panel of judges who have heard the appeal and not signed by any particular judge on the panel.”[83]

c. Where the Second Amendment stands today

Cases

Recall from our Article III Judicial branch discussion, President Donald Trump nominated three justices to the Supreme Court of the United States. Once nominated, the justices must then receive a simple majority vote of the Senate. In April 2017, the Republican majority in the Senate abolished the filibuster for Supreme Court confirmation hearings, thus ending debate on the nomination of Neil Gorsuch to the Court, and allowing the majority to confirm Gorsuch. Confirmations of Trump appointees Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett soon followed. Senate confirmation allows a check and balance on the composition of the Supreme Court of the United States.

New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen, 597 U.S. __ Fitzgerald, S. (2022)[84]

These appointments were controversial, to say the least. In 2022, the Supreme Court heard a challenge to concealed carry gun laws, seeking to extend the right established in Heller to possess guns in the home, to now do so in public. In New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen (2022), the challengers claimed that New York’s 109-year-old special permitting process for carrying a firearm outside the home violates the Second Amendment.[85] The Court held by a vote of 6-3, with all the conservative justices in the majority, in an opinion written by Justice Clarence Thomas, that the New York State law violates the Second Amendment (and Fourteenth Amendment) and invalidated the concealed carry rules in the law.[86] The new test for legislation and regulations, articulated by Justice Thomas, “requires courts to assess whether modern firearms regulations are consistent with the Second Amendment’s text and historical understanding.”[87]

Therefore, the new composition of the Supreme Court of the United States has the possibility to afford the expansion and clarification of current landmark cases, while producing new landmark cases.[88] In the fall of 2023, the Court will hear oral argument in United States v. Rahimi, a case in which the Court will decide if a Congressional law prohibiting the possession of firearms by persons subject to domestic-violence restraining orders, violates the Second Amendment.[89]

Below is an interactive timeline of the evolution of the Second Amendment. How does this timeline help you understand which rights were balanced by whom and when?

Timeline Sources[90]

Critical Reflections:

- How does the information and Musket reenactment picture help you understand what the forefathers anticipated when they wrote the Second Amendment? What additional factors should we consider as we explore how the Second Amendment evolved?

- Second Amendment enthusiasts insist that the individual’s right to bear arms are supreme against states’ and federal rights based on the wording and layout of the Amendment. Do you agree? Explain why or why not?

- Should Congress act to place more controls on the sale of guns given the increased frequency of mass homicides in our country? Would such an act encroach too heavily on the right to bear arms? Why or why not?

- While not the shortest, the Second Amendment leaves a lot to be interpreted. How would you modify it to reflect more clarity? Be sure to include the forefathers’ intentions.

- Should Congressional tools for argument such as the filibuster be eliminated at critical times in order for one party to gain advantage over another when facing the lifetime appointment of a Supreme Court Justice?

- Is the right defined in the Second Amendment an individual right, states’ right or a collective (federal) right?

- T. Forst (2016). Recreating the use of a musket. Photograph, Savannah, GA. ↵

- Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2020, March 12). Musket. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/technology/musket ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Annenberg Public Policy Center (n.d.). Justice Antonin Scalia in “Second Amendment: D.C. v. Heller and McDonald v. Chicago." Retrieved August 1, 2023 from https://www.annenbergpublicpolicycenter.org/guns-in-america-annenberg-classroom-releases-second-amendment-film/ ↵

- Harr, S. J., Hess, K. M., Orthmann, H. C., & Kingsbury, J. (2017). Constitutional Law and the Criminal Justice System (7th ed.). Wadsworth Publishing. ↵

- MILITIA, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- The battle of Lexington. Public domain. Library of Congress. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- PRESENTMENT, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- INDICTMENT, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Id. ↵

- A glossary of small arms across three wars. (2022, June 28). American Battlefield Trust. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/glossary-small-arms-across-three-wars#:~:text=By%201862%2C%20most%20Union%20soldiers,highly%20accurate%20long%2Drange%20weapon. ↵

- Fryling, T. F. M. (2014). Constitutional law in criminal justice. Wolters Kluwer. ↵

- Id. ↵

- United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542 (1875). ↵

- Id. at para. 17. ↵

- Rodriguez, V. (2019, May 1). This footnote provides a link to a timeline of the second amendment and gun control in the U.S.: Seventeen. https://www.seventeen.com/life/a19643402/second-amendment-gun-control-history/ ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Harr, 2017. ↵

- COMMERCE CLAUSE, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Art. I, §8, cl. 15. ↵

- United States Senate. (2020, January 21). U.S. senate: Constitution of the united states. Constitution of the United States. https://www.senate.gov/civics/constitution_item/constitution.htm ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Federalism: Scholar Exchange. The National Constitution Center. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. ↵

- United States Flag [cropped, text added]. Public domain. ↵

- RIGHT TO BEAR ARMS, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Harr, 2017. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Definition of infringe. (2023). In Merriam-Webster Dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/infringe#:~:text=fringe%20in%2D%CB%88frinj-,infringed%3B%20infringing,or%20the%20rights%20of%20another. ↵

- Shaw, W. L. (1966). The Interrelationship of the United States Army and the National Guard. Mil. L. Rev, 39–84. https://www.loc.gov/law/mlr/Military_Law_Review/27-100~1.pdf ↵

- Ibid, p.44. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- History.com Editors. (2020, August 26). Second amendment. HISTORY. https://www.history.com/topics/united-states-constitution/2nd-amendment, p. 1. ↵

- Akirn. (n.d.). Difference Between Federalist And Anti Federalists | annahof-laab.at. http://annahof-laab.at/typo3conf/ext/custom/analysis-of-body-and-mind/difference-between-federalist-and-anti-federalists.php ↵

- U.S. Const. Art. I, §8. ↵

- History.com Editors. (2020, August 26). Second amendment. HISTORY. https://www.history.com/topics/united-states-constitution/2nd-amendment, p. 2. ↵

- Levinson, S. (1988). The embarrassing second amendment. The Yale Law Journal, 637–659. https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=7254&context=ylj ↵

- Ibid, p. 688. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Morgan, E. S. (1989). Inventing the people: The rise of popular sovereignty in england and america (Revised ed.). W. W. Norton & Company, p.85-87. ↵

- STATE, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Oil on Canvas Portrait of Dred Scott; Now Ready - the Dred Scott decision. Public domain. Wikimedia Commons. ↵

- Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. 393, 417 (1857). ↵

- Levinson, 1988, p. 651. ↵

- Tribe, L. (1988). American Constitutional Law, 2d (University Treatise Series) (2nd ed.). Foundation Press. ↵

- United States v. Miller, 307 U.S. 174, 178 (1939). ↵

- Frye on the 2nd Amendment and the Peculiar Story of U.S. v. Miller. (n.d.). http://legalhistoryblog.blogspot.com/2007/04/frye-on-2nd-amendment-and-peculiar.html ↵

- Id. ↵

- U.S. v. Miller, 1939. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Wikimedia Commons. James Clark McReynolds portrait. https://sv.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fil:James_Clark_McReynolds_portrait.jpg ↵

- Id at 179. ↵

- Stevens, J. J. P. (2014). Six Amendments: How and Why We Should Change the Constitution (Illustrated ed.). Little, Brown and Company, p. 76. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- U.S. Chief Justice Warren E. Burger.. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:US_Chief_Justice_Warren_Burger_-_1971_official_portrait.jpg ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Printz v. United States, 521 U.S. 898 (1997). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- An Introduction to Constitutional Law » District of Columbia v. Heller. (n.d.). Nearer.com. https://conlaw.us/case/district-of-columbia-v-heller-2008/ ↵

- District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570 (2008). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- On Otis McDonald and his lawsuit challenging Chicago’s 1982 handgun ban. (n.d.). Chicago Magazine. https://www.chicagomag.com/chicago-magazine/january-2010/in-their-sights-lawsuit-challenging-chicagos-1982-handgun-ban-to-be-heard-by-supreme-court/. ↵

- Id. ↵

- District of Columbia v. Heller, 2008. ↵

- McDonald v. Chicago, 561 U.S. 742 (2010). ↵

- Elkins & McKitrick, 1993. ↵

- Rama. Electric weapon. CC BY-SA 2.0 FR. Wikimedia Commons. ↵

- Caetano v. Massachusetts, 136 S. Ct. 1027, 1027-1028 (2016). ↵

- Id. at 1028. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Fourth Amendment. (n.d.). LII / Legal Information Institute. Retrieved December 7, 2020, from https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution/fourth_amendment ↵

- PER CURIAM, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- SCOTUS Strikes Down New York’s Restrictive Carry Law. CRPA. https://crpa.org/news/blogs/nysrpa-v-bruen-decision-is-in/. ↵

- New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen, 597 U.S. ___________ (2022). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. at 23. ↵

- Washington Post. (2021, April 27). ↵

- United States v. Rahimi. (n.d.) Oyez. Retrieved July 15, 2023, from https://www.oyez.org/cases/2023/22-915 ↵

- Gray, S. (2021, April 29). Here’s a timeline of the major gun control laws in america. Time. https://time.com/5169210/us-gun-control-laws-history-timeline/; Right to bear arms timeline. (n.d.). Shmoop. Retrieved June 1, 2021, from https://www.shmoop.com/study-guides/civics/right-to-bear-arms/timeline; Rodriguez, V. (2019, May 1). A timeline of the second amendment and gun control in the U.S. Seventeen. https://www.seventeen.com/life/a19643402/second-amendment-gun-control-history/ ↵