Chapter 9 – Amendment IX and Amendment X: To Retain or To Reserve

Amendment IX & Amendment X

Richard J. Forst and Tauya R. Forst

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

9.1 Define the unfamiliar terms of the Ninth and Tenth Amendments.

9.2 Explain the parts of the Ninth and Tenth Amendments.

9.3 Explain the implicit rights of the Ninth Amendment not specifically mentioned in the Constitution.

9.4 Summarize the net powers bestowed, to whom the powers are bestowed upon, as related in the Tenth Amendment.

9.5 Describe the zone of privacy set forth in the Griswold case.

9.6 Explain the Supreme Court’s holdings in Roe v. Wade, Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey, and Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization.

z9.7 Explain the purpose of the inclusion of the Tenth Amendment in the Bill of Rights.

KEY TERMS

| Compelling State Interest | Penumbra of Rights |

| Construe | Right to Privacy |

| Enumerated Rights | Viability |

| Implied or Unenumerated Rights | Zone of Privacy |

| McCulloch v. Maryland |

Amendment IX

Passed by Congress September 25, 1789. Ratified December 15, 1791. The first 10 amendments form the Bill of Rights.

The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.

The 9th amendment of the Bill of Rights[1]

The 9th amendment of the Bill of Rights[1]

INTRODUCTION TO AMENDMENT IX

Legal analysts agree that the ambiguity in the Ninth Amendment presents interesting topics for those who chose to invoke it. In fact, Associate Justice Robert H. Jackson described his thoughts surrounding the Ninth Amendment. In “The Supreme Court in the American System of Government,” Justice Jackson, a noted legal scholar, admits that the Ninth Amendment “remains a mystery” to him.[2] Similarly, most legal scholars and lay persons alike agree that the Ninth Amendment remains vague. The final version of the Ninth Amendment (after five attempts by James Madison) leaves much to the imagination of those who debate its inclusion of natural or lack of natural rights.[3] We find it paramount to begin a conversation of this vastness, by defining some of the terms found in its twenty-one words. The depth of its effect can not be measured by the miniscule number of words. The Ninth Amendment was meant to be a living, breathing construct for additional individual rights to be vetted and born.

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT IX

The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.

Due to this living, breathing aspect of the United States Constitution and is vagueness of Amendment Nine, we begin by reviewing key terms to help develop a framework of understanding as we introduce some new terminology. Firstly, enumerate or enumeration is “[t]o count off or designate one by one; to list.”[4] The amendment speaks to those rights which are identified and established with a numerical counterpart in the beginning of the verbiage. Following this context is the term construed. Black’s Law Dictionary defines construe as “[t]o analyze and explain the meaning of (a sentence or passage.)”[5] The amendment lends credence to certain numbered rights which must (the legal force of the word, shall) not be used to analyze whether those rights are explicitly missing, disregarding its existence or diminish the value of others.

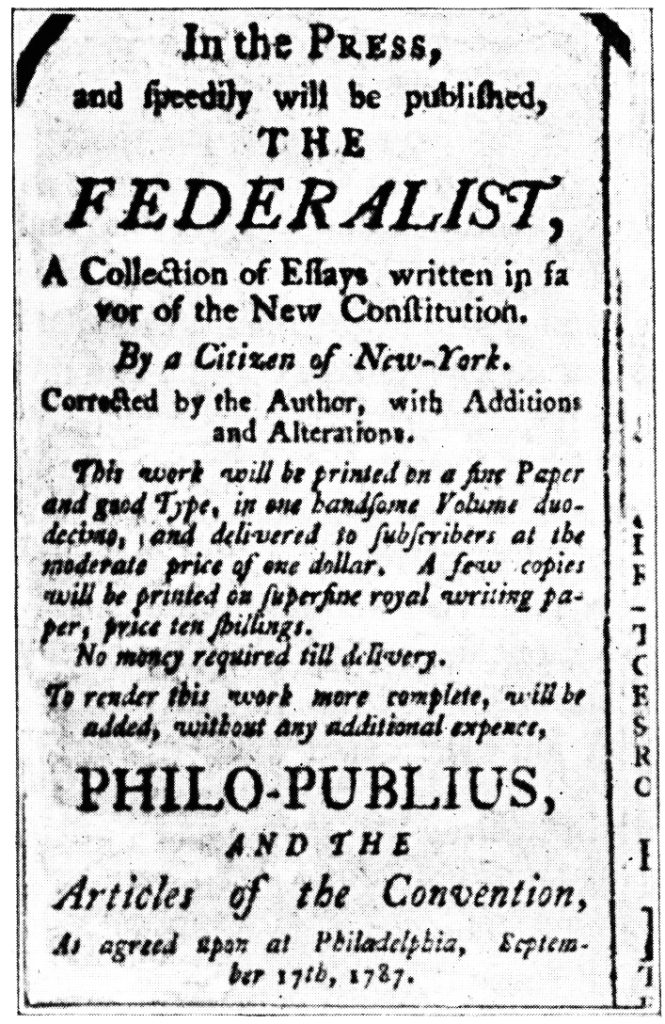

The Federalist Papers[6]

Scholars regard The Federalist Papers, originally referred to as The Federalist, as a compilation of 85 essays written in persuasive detail by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison culminating in 1788.[7] The essays were published under a pen name, leaving the original authors’ names unknown. These essays appeared in several New York state newspapers. In short, the purpose of the Federalist Papers was to encourage support to ratify the United States Constitution. The authors took extra attention and time to provide the necessary methodical explanation for each portion of the United States Constitution. “For this reason, and because Hamilton and Madison were each members of the Constitutional Convention, the Federalist Papers are often used today to help interpret the intentions of those drafting the Constitution.”[8]

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

The diametrically opposed positions of the Anti-Federalists and Federalists remain at the forefront of every debate regarding the United States Constitution. The Anti-Federalists advocated for individual rights to help balance the power of the federal government, while Federalists noted the controlled method of providing a limited number of individual rights would contradict the argument for additional rights and symbolize any additional rights as unconstitutional.

“Thus was born the Ninth Amendment, whose purpose was to assert the principle that the enumerated rights are not exhaustive and final and that the listing of certain rights does not deny or disparage the existence of other rights.”[9] Therefore, the Ninth Amendment was written to emphasize clarity of additional individual rights, while providing ambiguity to those who limited the rights to those being enumerated within the amendments.

Although the Ninth Amendment doesn’t provide explicit rights, SCOTUS has noted some implicit rights in many instances. We will explore how two such cases with very different legal issues have leveraged and highlighted the depth of the Ninth Amendment. In United Public Workers v. Mitchell (1947), the court examined a violation of the §9 and §15 of the Hatch Act of 1940, which is a federal law which seeks to protect a nonpartisan federal workforce.[10] In this case, several issues came before the court.

The appellants wanted the court to address: 1. an alleged jurisdictional issue barred by a deadline, 2. a justiciable issue for all appellants, if only one appellant violated the Hatch Act, and 3. §9 and §15 of the Hatch Act of 1940 as a Constitutional provision regarding federal employees.

The court gave an elaborate analysis of each of the first two legal procedural issues, while providing interpretation for the third issue. In fact, the court states that the political restrictions as stated in the §9 and §15 of the Hatch Act of 1940 are not unconstitutional. SCOTUS relied upon a penumbra of rights to help make this determination. The penumbra of rights stems from the First Amendment, the Third Amendment, Fourth Amendment, and Fifth Amendments. “The fundamental human rights guaranteed by the First, Fifth, Ninth and Tenth Amendments are not absolute, and this Court must balance the extent of the guarantee of freedom against a congressional enactment to protect a democratic society against the supposed evil of political partisanship by employees of the Government.”[11] This application of the explicit rights to a federal political issue pales in contrast to how the Ninth Amendment was eventually utilized within the Constitutional scheme of the country.

In comparison, the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) spotlighted the penumbra of rights which included the Ninth Amendment in other ways. Whereas its original construction may be argued, it is clear by the 1960s the Ninth Amendment was morphing into an important concept within SCOTUS. Its use landed on new concepts which SCOTUS deemed significant enough to acknowledge regardless of its direct enumeration or lack of enumeration.

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

It is interesting that the Supreme Court of the United States has never been asked to specifically interpret the vagueness or, for that matter, the meaning of the Ninth Amendment.

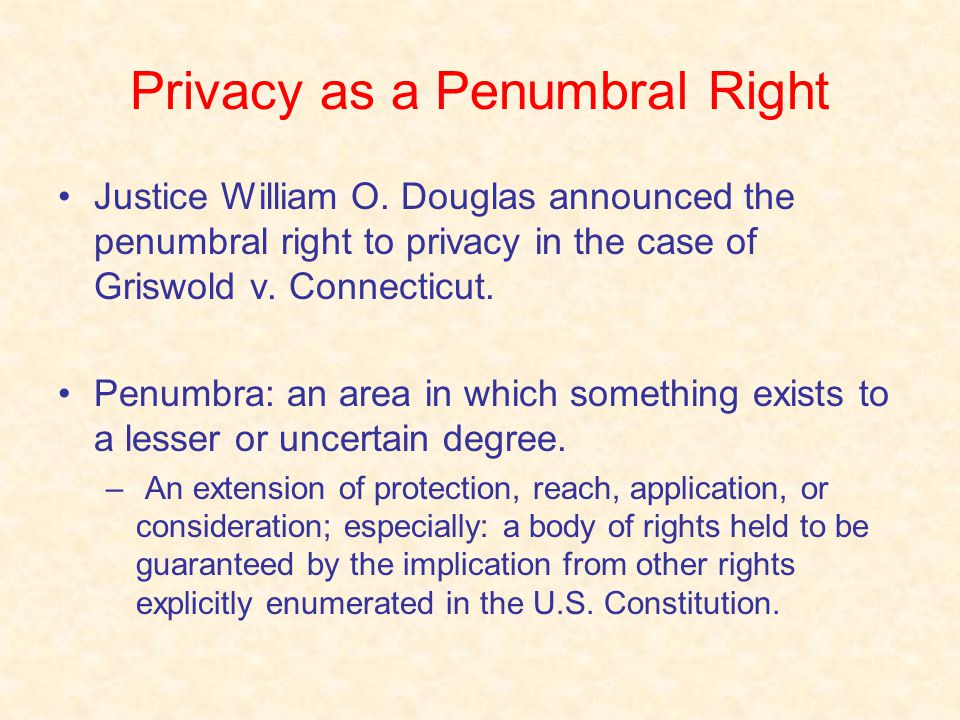

To this end, the Supreme Court of the United States instead explored and implemented new judicial concepts. One such concept, the zone of privacy, which Justice Louis Brandeis once defined as “the right to be left alone,” is not an enumerated right.[12] However, Black’s Law Dictionary defines zone of privacy as “[a] range of fundamental privacy rights that are implied in the express guarantees of the Bill of Rights.”[13] Additionally, the right to privacy, or even the word “privacy” is not mentioned in the United States Constitution. In 1965, this assumed inclusion of privacy would be addressed via landmark cases. In this way, the Supreme Court of the United States began to acknowledge inherent rights supported by the Ninth Amendment.

In Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), Griswold, the Executive Director of Planned Parenthood in Connecticut, was a named party. Griswold and her staff provided birth control services.[14] These services were a violation of the Connecticut law which read “Any person who assists, abets, counsels, causes, hires or commands another to commit any offense may be prosecuted and punished as if he were the principal offender.”[15] Griswold and a member of her staff were each found to be in violation of the law. The penalty for the violation was a $100 fine.[16] Griswold and her colleague appealed the case to the SCOTUS. The Court, in a 7-2 opinion, reviewed the question of whether the aforementioned Connecticut law interferes with the zone of privacy created by “several fundamental guarantees” including those which pre-date the United States Constitution, such as marriage.[17] Thus, the Court warned, if allowed to stand, the police would be endowed to enter the sacred bedrooms of married couples to determine illegal activities barring any legal authority to do so.[18]

The Court further explores and draws legal authority from other parts of the United States Constitution as a signal of support. The court identifies the First, Third, Fourth, Fifth, Ninth, and Fourteenth Amendments to provide this hedge of protection that does not explicitly state these rights of privacy, but has shown in times past a periphery approach to such rights. In short, SCOTUS admits that minus the extended interpretation of the First, Third, Fourth, Fifth and Fourteenth (by inclusion) Amendments, plus the ambiguity of the Ninth Amendment, the zone of privacy or the rights of privacy does not exist.[19] Griswold plainly states that the right to privacy is solely comprised of the penumbra of enumerated rights. Therefore, we are introduced to this legal concept of penumbras for one of the most pivotal rights for those on the soil of the United States of America. According to Black’s Law Dictionary, a penumbra is defined as “[a] surrounding area or periphery of uncertain extent.”[20] Thus, SCOTUS has acknowledged that specific rights and guarantees in the first ten amendments use this concept to support the implied rights – namely, the right to privacy. Notably, an implied right is defined as “[a] right inferred from another legal right that is expressly stated in a statute or at common law.”[21] Regardless of your interpretation of the Ninth Amendment, it is of utmost importance to recognize that the Supreme Court of the United States has extended the Ninth Amendment’s effect to include such implied rights as travel, right to vote, right to privacy as well as the right to one’s own self-care.[22]

Penumbra of Rights – Right to Privacy[23]

The controversial landmark case Roe v. Wade (1973), firmly established the right to privacy as fundamental, and required that any governmental infringement of that right to be justified by a compelling-state-interest test.[footnote]Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973)[/footnote] Black’s Law Dictionary defines a compelling-state-interest test is defined as “[a] method for determining the constitutional validity of a law, whereby the government’s interest in the law and its purpose are balanced against an individual’s constitutional right that is affected by the law.”[24] More importantly, laws are deemed valid when the government’s interest is strong enough.[25] In fact, “[t]he compelling-state-interest test is used, [for example], in equal-protection analysis when the disputed law requires strict scrutiny.”[26] In Roe, the Court ruled that the state’s compelling interest in preventing abortion and protecting the life of the mother outweighs a mother’s personal autonomy only after the viability of the fetus.[27]

According to Roe, the fetus is deemed viable if it is “…potentially able to live outside the mother’s womb, albeit with artificial aid.”[28] Additionally, viability usually occurs “about seven months (28 weeks) but may occur earlier, even at 24 weeks.”[29] Before viability, the mother’s right to privacy limits state interference due to the lack of a compelling-state-interest test according to Sharp (2014).[30] First trimester, the mother’s personal autonomy dictates the abortion. Second trimester, the state’s compelling interest is balanced with protecting the life of the mother. Finally, third trimester, the state’s important and legitimate compelling interest sets forth the basis for an abortion, if one is to be performed. Therefore, Roe previously set forth the right to abortion based upon the three trimesters in birth by balancing the state’s compelling interest and the mother’s personal autonomy.

The Supreme Court reaffirmed its holding in Roe, granting a right to an abortion, in Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey (1992).[31] The Judgment of the Court was announced by Justices O’Connor, Kennedy and Souter, with Justices Blackmun and Stevens concurring (all five of whom had been nominated by Republican Presidents–see below), resulting in a 5-4 majority.[32] The Judgment stated, “We conclude that the basic decision in Roe was based on a Constitutional analysis which we cannot now repudiate….The woman’s right to terminate her pregnancy before viability is the most central principle of Roe v. Wade. It is a rule of law and component of liberty we cannot renounce…”[33]

The right to an abortion established by Roe (1973) and reaffirmed by Casey (1992) was overturned by a 6-3 majority of the Court in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022).[34] The Court’s six-person majority (nominated by Republican Presidents) held that the Constitution does not confer a right to abortion, and that the authority to regulate abortion is returned to the people and their elected representatives.[35] Justice Alito, writing for the majority, stated, “The Constitution makes no reference to abortion, and no such right is implicitly protected by any constitutional provision…any such right must be ‘deeply rooted in this Nation’s history and tradition’ and ‘implicit in the concept of ordered liberty.'”[36] Alito further wrote, “Stare decisis, the doctrine on which Casey’s controlling opinion was based, does not compel unending adherence to Roe’s abuse of judicial authority. Roe was egregiously wrong from the start. Its reasoning was exceptionally weak, and the decision has had damaging consequences.”[37]

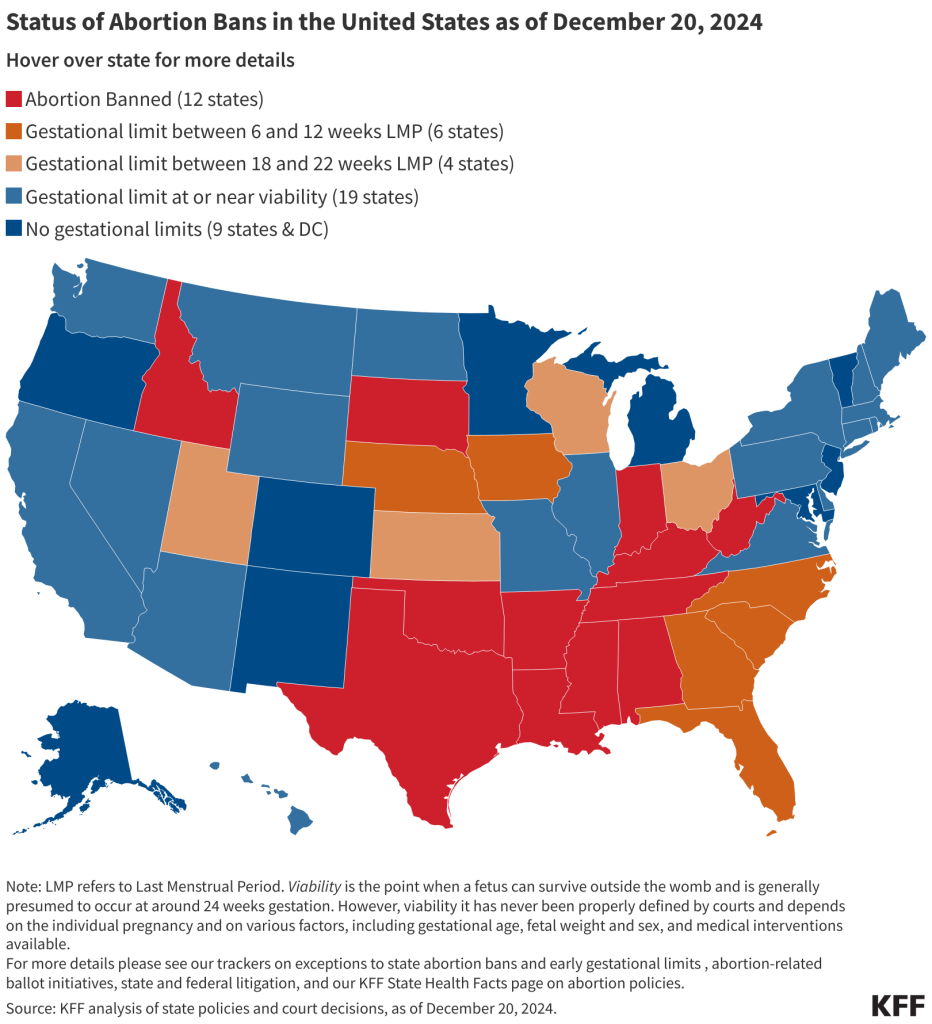

Bans on Abortion[38]

Within the first year after Dobbs was announced, and the decision whether or not to guarantee the right to an abortion had been turned over to the individual States, the following States banned abortion entirely: Alabama, Arkansas, Idaho, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, West Virginia, and Wisconsin. Other states passed Gestational Limits on abortions: Georgia, after 6 weeks, Nebraska and North Carolina after 12 weeks, Arizona and Florida after 15 weeks, and Utah, after 18 weeks.[39]

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

In an unusual show of solidarity, the three most liberal justices—Breyer, Sotomayor and Kagan—issued a joint opinion in bitter dissent from the Dobbs majority. The right recognized in Roe (1973) and Casey (1992) “does not stand alone,” they wrote. “To the contrary, the Court has linked it for decades to other settled freedoms involving bodily integrity, familial relationships, and procreation. Most obviously, the right to terminate a pregnancy arose straight out of the right to purchase and use contraception. In turn, those rights led, more recently, to rights of same-sex intimacy and marriage. They are all part of the same constitutional fabric, protecting autonomous decisionmaking over the most personal of life decisions.”[40]

Amendment X

Passed by Congress September 25, 1789. Ratified December 15, 1791. The first 10 amendments form the Bill of Rights.

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

INTRODUCTION TO AMENDMENT X

The Tenth Amendment follows the course of the Ninth Amendment, in that it still portrays some form of ambiguity and vagueness if taken solo. On the other hand, some critics believe the Tenth Amendment provides clarity of power regarding the reservations of said power. What becomes questionable is what the power is and how it should be interpreted when applied to case law and ordinances, codes, and statutes. Within this debate, we find a carefully crafted compromise for the positions of the Federalists and Anti-Federalists. The Federalists continued to lay hold to the concept of a strong and notable federal or central government, while the Anti-Federalists delighted in opposing said federal or central government.[41] In short, the Tenth Amendment manages to avert any strict parameters, while encouraging and supporting the states as they implement, institute, and introduce their own laws as long as it doesn’t compete or contradict the federal powers. Then the question remains – what powers are being addressed in the Tenth Amendment.

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT X

The 10th amendment of the Bill of Rights[42]

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

According to the language of the Tenth Amendment, the powers being addressed begins first with those powers not delegated in the United States Constitution to the federal government. The implication of the first clause is to place the emphasis on an enumerated power which is “[a] political power specifically delegated to a governmental branch by a constitution.”[43] This implication then extends and is further developed by the next clause. This clause coupled with the initial clause further directly prohibits States’ powers held by the Constitution, thus leaving the states with the remainder powers officially known as reserved powers. Reserved powers differ in that they are political powers “that [are] not enumerated or prohibited by a constitution, but instead is reserved by the Constitution for a specified political authority, such as a state government.”[44]

Compared to other amendments, the Tenth Amendment is comprised of only twenty-eight words and one sentence. Similar to the Ninth Amendment, one should not be discouraged by the lack of words to express this very powerful sentiment of those who support the Tenth Amendment. According to the Annals of Congress, the term “expressly” was purposely absent before “delegated” from the Tenth Amendment.[45] Additionally, this did not provide support for granting the federal government powers or reservation of power to the states as evidenced in “…Madison’s remarks in the course of the debate which took place while the proposed amendment was pending concerning Hamilton’s plan to establish a national bank…”[46] This would later be explored in McCulloch v. Maryland.[47] The Tenth Amendment, like all other amendments, was placed with the verbiage used to address particular concerns within the states. It was meant to create a framework of separation of powers between the governments and all who they served in this newly formed entity. “…[T]he Tenth Amendment was inserted into the Constitution largely to relieve tension and to assuage the fears of states’ rights advocates, who believed that the newly adopted Constitution would enable the federal government to run roughshod over the states and their citizens.”[48]

McCulloch v. Maryland[49]

To this end, the fight between the state and federal government was real based upon its appearance in the Articles of Confederation. Most individuals recognized that the role of the states within that document was paramount and vowed to present a different view of balancing interests. The balancing of interests looks at the rights of the federal government, state governments, and the individuals. Each of these rights serves as a reminder that all interests are necessary to meet the viewpoints of all stakeholders involved in governmental decisions. In actuality, the first ten amendments, also known as the Bill of Rights, was drafted when the First Congress met and the balancing of the interested began to unfold.

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

The Supreme Court models the balancing of federal and state interests in the following case. We find the beginnings of the Supreme Court of the United States’ interpretation of the Tenth Amendment in McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), where the question before the court was two-fold. In McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), two central issues were before the composition of seven justices. The justices, most of which were in favor of states’ rights, were taxed with determining whether the Congressional authority existed to create a national bank; additionally, whether the states maintained Constitutional authority to tax said national bank?[50]

With Chief Justice Marshall at its helm and writing the majority, unanimous decision, the court supported Congress in its authority to create the bank, but denied the states the right to tax the entity reiterating federal authority in most situations.[51] The court emphasized the vast federal authority vested in Congress, reminding the nation that any law created by Congress is rooted in Article I of the United States Constitution which is the supreme law of the land.[52] The courts would review, extend, and reduce its interpretation of the Tenth Amendment regarding federal taxing power, federal police power, as well as federal regulations affecting state activities.

The Ninth and Tenth Amendment together work to examine enumerated and unenumerated rights, as well as reserved powers while fully defining federalism and its relationship to federal, state, and individual rights. As Federal activity has increased, so too has the problem of reconciling all interests “…as they apply to the Federal powers to tax, to police, and to regulations such as wage and hour laws, disclosure of personal information in recordkeeping systems, and laws related to strip-mining.”[53]

Critical Reflections:

- Is the Right to Privacy an unenumerated right the Supreme Court should continue to protect? Why or why not?

- What is a penumbra of rights? When was this term first introduced? Where was this term first introduced?

- Is there a limit to the “reserved powers”? If so, what are the limits?

- Read how McCulloch v. Maryland (1819)’s 200th birthday discussion remains relevant today. Read how one Constitutional expert applies current day implications here. How is Congress described in this article? Do you agree or disagree? Why?

- Image by Epic Top 10 Site. 9th Amendment. CC BY. Flickr. ↵

- Jackson, R. (1963). The supreme court in the american system of government. Harper & Row. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- ENUMERATE (enhanced), Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- CONSTRUE, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- An Advertisement of The Federalist. Public domain. Wikimedia Commons. ↵

- Research guides: Federalist papers: Primary documents in american history: Full text of The federalist papers. (n.d.). Federalist Papers: Primary Documents in American History. Retrieved November 12, 2020, from https://guides.loc.gov/federalist-papers/full-text ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Smentkowski, B. (n.d.). Britannica. Tenth Amendment. Retrieved August 30, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Tenth-Amendment. ↵

- United Public Workers v. Mitchell, 330 U.S. 75, 95-96 (1947). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Skousen, 2002. The right to be left alone. Foundation for Economic Education. https://fee.org/articles/the-right-to-be-left-alone/ ↵

- ZONE OF PRIVACY, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- PENUMBRA, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- RIGHT, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Does the Constitution guarantee a right to privacy. (n.d.). https://slideplayer.com/slide/4533648/ ↵

- COMPELLING-STATE-INTEREST TEST, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Roe v. Wade (1973). ↵

- Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113, at 161 (1973). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992). ↵

- O’Brien, D. M., & Silverstein, G. (2020). Constitutional Law and Politics: Struggles for power and governmental accountability. p. 1285-1286. ↵

- Planned Parenthood v. Casey, 1992. ↵

- Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, 597 U.S. ___ ___ (2022); Hamm, A. (2023, July 20). Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization - SCOTUSblog. SCOTUSblog. https://www.scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/dobbs-v-jackson-womens-health-organization/. ↵

- Hamm, A. (2023, July 20). Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization - SCOTUSblog. SCOTUSblog. https://www.scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/dobbs-v-jackson-womens-health-organization/. ↵

- Dobbs v. Jackson, 2022. ↵

- O’Brien, D. M., & Silverstein, G. (2020). Constitutional Law and Politics: Struggles for power and governmental accountability. p.1304 ↵

- Abortion in the United States dashboard. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. KFF. ↵

- Times, N. Y. (2023, July 12). Abortion bans across the country: Tracking restrictions by state. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/us/abortion-laws-roe-v-wade.html ↵

- O'Brien and Silverstein, pp. 1301-1302. ↵

- Levy, M. (n.d.). Reserved powers. LII / Legal Information Institute. Retrieved March 3, 2021, from https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution-conan/amendment-10/reserved-powers ↵

- Image by Epic Top 10 Site. 10th Amendment. CC BY. Flickr. ↵

- POWER, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- GPO. (n.d.). Tenth amendment. Authenticated U.S. Government Information GPO. Retrieved December 11, 2020, from https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CONAN-1992/pdf/GPO-CONAN-1992-10-11.pdf. ↵

- GPO, (n.d.). ↵

- McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. 316 (1819). ↵

- Levy, 2020. ↵

- Centpacrr. Daniel Webster 1824 signature. CC BY-SA 3.0. Wikimedia Commons. ↵

- McCulloch v. Maryland (1819). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Levy, M. (n.d.). Reserved powers. LII / Legal Information Institute. Retrieved March 3, 2021, from https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution-conan/amendment-10/reserved-powers ↵