Chapter 5 – Amendment IV: The Rule & The Exceptions to The Rule…Not Privacy

Amendment IV

Richard J. Forst and Tauya R. Forst

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

5.1 Identify the unfamiliar terms of the Fourth Amendment.

5.2 Explain the two parts of the Fourth Amendment.

5.3 Define search. Define stop. Define seizure. Define arrest. Define warrant.

5.4 Compare the differences among search, stop, seizure, and arrest.

5.5 Describe the exceptions to the warrant requirement in the Fourth Amendment.

5.6 Compare the differences between a search with a warrant and search without a warrant.

5.7 List the advantages of obtaining a warrant prior to a search.

5.8 Explain the exclusionary rule.

5.9 Identify when the exclusionary rule applies.

5.10 Define the fruit of the poisonous tree.

5.11 Explain what happens to evidence and a court case when applying the exclusionary rule.

KEY TERMS

| Admissible evidence | Inadmissible |

| Affidavit | Motion to Suppress |

| Agent | Plain view/Plain sight doctrine |

| Attenuation Doctrine | Probable Cause |

| Bright-line Rule | Qualified Immunity |

| Case-by-Case Rule | Reasonableness Clause |

| Consent | Reasonable Suspicion |

| Admissible evidence | Inadmissible |

| Affidavit | Motion to Suppress |

| Agent | Plain view/Plain sight doctrine |

| Attenuation Doctrine | Probable Cause |

| Bright-line Rule | Qualified Immunity |

| Case-by-Case Rule | Reasonableness Clause |

| Consent | Reasonable Suspicion |

| De-escalation | Search Incident to Lawful Arrest |

| Exceptions | Stop-and-Frisk |

| Exigent Circumstances Doctrine | Unreasonable search and seizure |

| Exclusionary Rule | Use of Force |

| Fruit of the Poisonous Tree | Warrant |

| Harmless Error Doctrine |

Getting Started

First determine how many parts exist in the Fourth Amendment. This will require a literal reading of each part of the amendment. Once we determine the parts, we can understand the verbiage of the United States Constitution. The Fourth Amendment is usually followed by statements which include unlawful, illegal and unreasonable searches and seizures (words found in the actual United States Constitution). Please note a reading of the Fourth Amendment indicates its important rule which you will find later in the chapter. In Terry v. Ohio (1968), Chief Justice Warren explained that the Fourth Amendment applied to all situations in which a law enforcement agent “accosts an individual and restrains [his or her’s] freedom to walk away.”[1] Therefore, we define unreasonable search and seizures here. According to Cornell Law’s Legal Information Institute,

“An unreasonable search and seizure is a search and seizure executed

1) without a legal search warrant signed by a judge or magistrate describing the place, person, or things to be searched or seized or

2) without probable cause to believe that certain person, specified place or automobile has criminal evidence or

3) extending the authorized scope of search and seizure.

An unreasonable search and seizure is unconstitutional, as it is in violation of the Fourth Amendment, which aims to protect individuals’ reasonable expectation of privacy, against government officers.”[2]

Amendment IV

Passed by Congress September 25, 1789. Ratified December 15, 1791. The first 10 amendments form the Bill of Rights.

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

Fourth Amendment word cloud from United States Courts[3]

INTRODUCTION TO AMENDMENT IV

In most scenarios where an agent conducts a search without a warrant, one question remains. Are the actions of the agent reasonable according to the Fourth Amendment? To adequately address this question, we must first define and identify which agents are subject to the Fourth Amendment. Black’s Law Dictionary defines an agent as “[s]omeone who is authorized to act for or in place of another; a representative.”[4] There are many types of agents identified as being subject to the Fourth Amendment such as: law enforcement agents, federal law enforcement agents, officers, police officers, cops, deputies, sheriffs, detectives, marshals, patrolmen, patrolwomen, peace officers, and troopers to name a few. Similar to other amendments in the Bill of Rights, the Fourth Amendment is a direct response to the experience of the colonists.

The Fourth Amendment’s direct response was addressed in the Saman Case (1603). The Fourth Amendment addressed the Crown’s unauthorized entry of the King’s men in legal arenas.[5] Saman’s case celebrated the concept that “[e]very man’s house is his castle” and balanced the homeowner’s right against unlawful entry of the King’s agents with the agents’ authority to enter to effectuate an arrest.[6] This authority is known as a writ of assistance. The writ of assistance is a “…a writ issued by a superior colonial court authorizing an officer of the Crown to enter and search any premises suspected of containing contraband.”[7] History notes that this writ and its impact was said to be the catalyst for the American Revolution in 1761.[8]

Although the Fourth Amendment remains central to American history, Steinberg notes that legal scholars maintain four differing interpretations of its meaning.[9] First, most legal analysts believed the Fourth Amendment Framers sought to force a warrant preference rule as well as a basic reasonable standard for searches and seizures. Unfortunately, there is little to no historical support for this and the next interpretation.[10] Second, the most widely regarded interpretation is an objective and original framers’ view of the Fourth Amendment which indicated that the Fourth Amendment was meant to apply to searches of homes. Third, Professor Akhil Reed Amar provided an interpretation which centers on the warrant as a threatening tool which requires governmental limitations. Fourth, scholars note and dismiss the final interpretation based upon the Fourth Amendment’s ambiguous history as meritless. Accordingly, the expansion of the Fourth Amendment may appear contradictory in nature, considering its original focus.

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT IV

Two Parts of the Fourth Amendment

Part I: Reasonableness Clause

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated,

Reasonable is a difficult term to define. In the legal realm, the reasonable person standard was identified to help judges and legal scholars articulate what is appropriate, fair, and moderate regarding a particular action or set of circumstances. This term calls for much deliberation and is typically reduced to judicial interpretation. In Cass v. State (1933), the court noted that a reasonable analysis requires “…having the faculty of reason, rational, governed by reason not immoderate or excessive, honest, equitable, [and] tolerable.”[11]

Reasonable encompasses many aspects for consideration when applying this concept in a case. Of course, one can not define reasonable using the same word (reasonable) in its definition. But we must note that the reasonableness clause is one of the two clauses of the Fourth Amendment. The reasonableness clause sets forth the requirement for searches and seizures with a warrant. In fact, “[a]ll searches and seizures under the Fourth Amendment must be reasonable and no excessive force shall be used. Reasonableness is the ultimate measure of the constitutionality of a search or seizure.”[12] This would not be a definition, but simply a restatement. For this reason, we must delve into other examples of how the court views this ambiguous term.

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) defined reasonableness in the United States v. Knights (2001) case as a balancing of individual rights against both federal and state rights.[13] Reasonableness of a search is set forth with specificity in Wyoming v. Houghton (1999). SCOTUS explained reasonableness of a search and determined “…by assessing, on the one hand, the degree to which it intrudes upon an individual’s privacy and, on the other hand, the degree to which it is needed for the promotion of legitimate governmental interests.”[14]

Reasonable Expectation of Privacy[15]

In evaluating whether an individual’s Fourth Amendment rights have been violated by a search, a court must first determine that the individual had a “reasonable expectation of privacy.” The Supreme Court held in O’Connor v. Ortega (1987) that a doctor in a public hospital had a reasonable expectation of privacy in his office because it was occupied by him only. Additionally, he occupied it for more than 17 years. Dr. Ortega was accused of stealing funds from patients and sexual harassment. The Court held that the reduced expectations of privacy that public employees face on the job are only those that are work related to the agency. Being an employee means that a person should expect that private items in their office are actually private.[16] The Court determined that it was not reasonable to search through all of Doctor Ortega’s private items in his office; therefore, the search violated the Fourth Amendment. [17]

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

As previously noted, individual rights must always be balanced with those of the federal and state governments. This theme is interwoven throughout the entire United States Constitution as the foundation of the document was meant to be a check and balance upon the cooperative efforts of individuals, states, and federal government.

Additionally, reasonableness requires a specific analysis of a long held legal standard for searching – probable cause. Chief Justice Warren further cautioned in Terry v. Ohio (1968), one should note that the law enforcement agent’s actions are central to reviewing the actions of the suspect as opposed to viewing the suspect’s actions as central while determining the validity of the law enforcement agent’s actions.[18] Thus, law enforcement agents must seek to describe their supportive evidence to a stop-and-frisk based upon “… specific and articulable facts which, taken together with rational inferences from those facts,” would draw the conclusion from a neutral magistrate or (judge) that the law enforcement agent “…of reasonable caution would be warranted in believing that possible criminal behavior was at hand and that both an investigative stop and a frisk was required.”[19]

Furthermore, Black’s Law Dictionary defines stop-and-frisk as “[a] police officer’s brief detention, questioning, and search of a person for a concealed weapon when the officer reasonably suspects that the person has committed or is about to commit a crime.”[20] As identified, stop-and-frisk includes a legal mechanism for search and seizures with or without a warrant. “The stop-and-frisk, which can be conducted without a warrant or probable cause, was held constitutional by the Supreme Court in Terry v. Ohio (1968).”[21] Reasonable suspicion must exist for both the stop and the frisk.

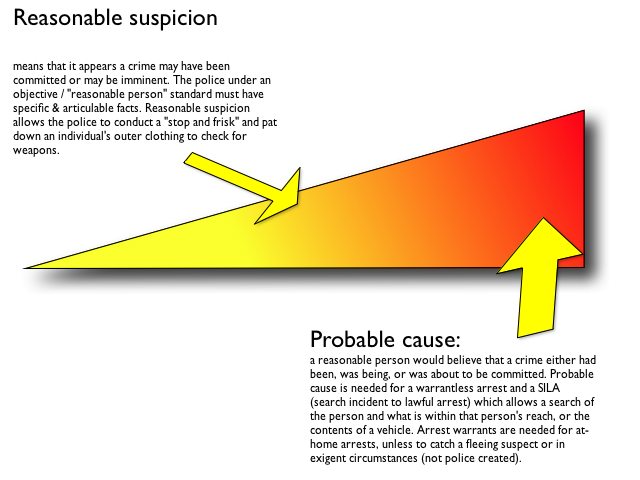

Reasonable Suspicion

Reasonable suspicion v. Probable cause[22]

Therefore, reasonable suspicion requires a review of four specific questions:

- Does the agent have a warrant for the search?

- Does the agent believe that the person has committed, will commit or is presently committing a crime?

- Does the agent have the ability to provide specific and articulable facts about this crime prior to the search?

- Does the agent believe that the person may be “… armed and presently dangerous?”[23]

The Bright-Line Rule or Totality of the Circumstances

When the courts determine if a search is unreasonable, they apply one of two viewpoints: the bright-line rule or the totality of the circumstances test. The bright-line rule is defined as the ability “[t]o decide a legal point; to make an official decision about a legal problem.”[24] Furthermore, the Bright-line rule is a controversial test, but legal practitioners tend to believe that it provides a simplistic approach to completing analysis.

a. Evaluating Legality of Searches

Within the legal arena, in Schneckloth v. Bustamonte (1973), the two-part issues before the court were

1) whether the the court of appeals erred when it held that the search of the car was invalid because the state failed to show consent given with knowledge that it could be withheld and

2) whether the claims relating to search and seizure are available to a prisoner filing a writ of habeus corpus?[25]

In fact, the law enforcement agents would have the breadth and depth necessary to appropriately manage realistic investigations. Therefore, the court held “whether consent is voluntary can be determined from the totality of the circumstances. It is unnecessary to prove that the person who gave consent knew that he had the right to refuse.”[26] Further, in Ohio v. Robinette (1996), the court extended the analysis indicating that “[r]easonableness, in turn, is measured in objective terms by examining the totality of the circumstances.”[27] Most courts implore the totality of the circumstances test using a case-by-case analysis. According to Black’s Law Dictionary, totality of the circumstances test is defined as “[a] standard for determining whether hearsay (such as an informant’s tip) is sufficiently reliable to establish probable cause for an arrest or search warrant.”[28]

Ultimately, the courts follow one of two viewpoints (as to whether a search is deemed unreasonable or not): apply one rule to all cases (bright-line rule) or what more courts tend to choose more often, the totality of the circumstances (case-by-case rule). A case-by-case rule is defined as a legal process “used to describe decisions that are made separately, each according to the facts of the particular situation.”[29] Totality of the circumstances is based upon all the evidence presented to the judge, not just one factor. The totality consideration determines whether probable cause for a warrant exists.[30] In this instance, the judge’s consideration involves whether a reasonable person would trust what officers have set forth.[31] If the judge is not convinced of these claims, a judge may request that an officer return with additional information to support his or her claim.[32] The latter viewpoint appears to be more inclusive in its application which tends to discount biases in the opinion processes.

Part II: Warrant Clause

and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

On the other hand, the Warrant clause sets forth the specific requirements for conducting a search. Further, it provides the specific items necessary to validate a search when executing the search according to a warrant. A warrant is defined as “[a] writ directing or authorizing someone to do an act, especially one directing a law enforcer to make an arrest, a search, or a seizure.”[33] Warrants are a necessary component for law enforcement agents to conduct searches such as a search warrant, an arrest warrant, an administrative warrant, a bench warrant, and a seizure warrant.

However, if one believes reasonableness is difficult to define, then probable cause may follow in stride. The Fourth Amendment (ratified 1791) sets the legal standard stage of how an agent will be aware of their ability to identify probable cause. Probable cause was first interpreted by the Supreme Court in Locke v. United States (1813) when the court defined the term by stating what it is not.[34] Chief Justice John Marshall formulated how we should review this constitutional verbiage. As he explained probable cause is defined as the ability to determine a “means less than evidence which would justify condemnation or conviction,” by acknowledging an officer’s responsibility to prove “more than bare suspicion” as noted in Brinegar v. United States (1949).[35]

Probable Cause

In essence, probable cause is a term which requires context of a fact pattern to fully understand. Consider the different ways probable cause may arise. Probable cause may arise as an agent obtains a warrant from a magistrate – a probable cause affidavit. Probable cause may arise as an officer in the field conducting a warrantless search – probable cause standard. Further, probable cause is defined by Black’s Law Dictionary as “[a] reasonable ground to suspect that a person has committed or is committing a crime or that a place contains specific items connected with a crime.”[36] Finally, probable cause may arise in a hearing conducted by a judge to hold over a client – a probable cause hearing. At any rate, probable cause requires an agent to explain the reason and purpose of the search prior to conducting the search. Legal standards for probable cause may be explained using an objective or subjective approach depending upon the way each of the probable cause options are leveraged in the criminal justice system. In this instance, probable cause is explained in an objective manner.

In Brinegar (1949), the courts ruled that it was reasonable to infer that Brinegar transported liquor as the agent observed Brinegar loading liquor. As a result, Brinegar was arrested for transporting liquor previously.[37] Brinegar personally confirmed his use of liquor when questioned by the officers. Consequently, the liquor was admissible evidence and Brinegar was charged and convicted of violating the Federal Liquor Enforcement Act. According to Black’s Law Dictionary, admissible evidence is defined as “[s]omething (including testimony, documents, and tangible objects) that tends to prove or disprove the existence of an alleged fact; anything presented to the senses and offered to prove the existence or nonexistence of a fact.”[38] The judge recognized how the explanation may appear in hindsight, but maintained the decorum of a factual or contextual analysis in confirming probable cause existed at the time of arrest. Thus it is important to remember as law enforcement agents utilize probable cause that it is done so with the rule in mind. The rule of the Fourth Amendment indicates that all searches must be conducted through the legal standard of probable cause as previously explained.

This general rule provides the necessary protections for how law enforcement agents should conduct searches as well as what level of expectation persons who come in contact with agents should expect.

In this instance, the rule of the Fourth Amendment states that any search must occur with a search warrant which requires three items per the Fourth Amendment.

First, the agent must obtain probable cause to believe that the searched items support that a crime has or will occur.

Third, the agent must obtain an oath or affirmation of the searched items which support that a crime has or will occur.

If all three items exist, then this information will culminate into a judge’s signature affixed to a warrant.

As we begin to study case law and the affects of local, state, and federal statutory law, we recognize that exceptions to this rule are common. Exceptions are defined as “…formal objection[s] to a court’s ruling by a party who wants to preserve an overruled objection or rejected proffer for appeal.”[39] However, it is important that those who seek to enforce the rule of the Fourth Amendment, immediately make the connection to the possibility of any exceptions which may exist.

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

Exceptions were meant to work in tandem with the rule, not instead of the rule. In other words, agents should concentrate on probable cause where available as any other legal standard works to reduce the authority and scope of the search resulting in a limited search.

Execution of a Warrant

Warrant Execution[40]

A police officer must execute a warrant once it has been issued by a judge or magistrate. A private citizen cannot execute a warrant. When a police officer executes a warrant, the media or other third parties cannot accompany the officer. This rule was set forth in Wilson v. Layne (1999), when the Supreme Court considered whether a newspaper reporter and photographer should be permitted to accompany the police on the execution of a warrant.[41] In keeping with the framers’ interest in protecting the right to privacy in homes, the Court indicated this practice was impermissible. The Court reasoned that police action pursuant to a warrant is reasonable only if the action is related solely to the objectives of the warrant.[42] In this case, the Fourth Amendment expectation of privacy trumped the First Amendment freedom of the press.[43]

Generally, search warrants should be executed as soon as possible after they are issued. Federal rules require execution within ten days of issuance. Searches should be conducted within daytime hours (6:00 a.m. to 10:00 p.m.), unless the alleged criminal activity is occurring at night, such as drug activity. In addition, a “no-knock” warrant can be requested if officers can demonstrate that knocking and announcing their presence would put them or others in danger. In order to obtain such an order, the Supreme Court held in United States v. Ramirez (1998) that an officer need merely prove that he has reasonable suspicion that he should not knock.[44] How long must an officer wait after knocking and announcing to enter? In United States v. Banks (2003), the Court held 15 to 20 seconds was a reasonable wait time. The Supreme Court of the United States posited that the officer could assume that 15 to 20 seconds is enough time for the suspect to begin destroying evidence.[45]

Each knock and announce case must be considered based upon its own facts and the totality of the circumstances, including the following factors:

1. The size, design and layout of the premises {to be searched or seized};

2. The nature of the offense, including the possibility of destroying evidence and the possibility that the suspect will be dangerous; and

3. The time of day that the search is being conducted.[46]

a. Cases

Chimel was arrested when law enforcement agents served a valid arrest warrant. Agents requested to look around Chimel’s home and Petitioner denied the request. Agents did not receive consent from Chimel or his wife. Although consent was denied, agents persisted to search Chimel’s home and obtained items which were used to convict Chimel. The Supreme Court in Chimel v. California (1969) held that the items used were unconstitutionally obtained – due to the lack of consent obtained “on the basis of the lawful arrest.”[47] It is of note that this was a warrantless search as it could not be connected to the lawful arrest or another constitutional grounds to legally execute the search. Hence, it was not a search “incident to that arrest.”[48]

It is important to recall that the general rule for conducting a search is that one must obtain a warrant. Recall, the legal standard for the Fourth Amendment requires probable cause in order to conduct searches. However, in some instances, a lesser legal standard appears to be constitutional.

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

In Terry v. Ohio (1968), the landmark case which reduced the legal standard of probable cause to reasonable suspicion was created within a limited context.[49] Reasonable suspicion, as a new limited legal standard allowed agents to search in uniquely specific circumstances, while placing legal restrictions on the atypical search.[50]

While patrolling a familiar area, a detective (with 39 years of experience) observed Terry and others proceed alternately back and forth along the same route, viewing the same store more than 20 times. The detective suspected Terry and friends were “casing the building” (reviewing the area for a possible robbery) in Terry v. Ohio (1968).[51] The detective approached and began a brief questioning before he patted down Terry to check for a weapon. The detective continued to question everyone as he moved Terry and others into the store. Ultimately, the detective recovered weapons from Terry and friends. Terry was arrested and charged with carrying a concealed weapon. Defense counsel moved to suppress this evidence. The court held that the evidence was constitutionally obtained.[52] The court recognized and introduced a new legal standard of reasonable suspicion.[53] Finally, reasonable suspicion is limited and must include the analysis that the agent does not have probable cause.[54]

The agent may conduct a limited search of the person’s outer garments without probable cause if the agent has:

Part III: Searches With A Warrant

a. Comparative Table 5.1: Types and Legal Authority are missing below. Please complete this information

| Legal tool | Searches | Stops | Seizures | Arrests |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elements | (1) the warrant must be filed in good faith by a law enforcement officer; (2) the warrant must be based on reliable information showing probable cause to search; (3) the warrant must be issued by a neutral and detached magistrate; and (4) the warrant must state specifically the place to be searched and the items to be seized. | When a police officer has a reasonable suspicion that an individual is armed, committing, or about to commit, in criminal conduct, the officer may briefly stop and detain an individual for a pat-down search of outer clothing. A Terry stop is a seizure within the meaning of Fourth Amendment. | Two elements must be present to constitute a seizure of a person. First, there must be a show of authority by the police officer. Presence of handcuffs or weapons, the use of forceful language, and physical contact are each strong indicators of authority. Second, the person being seized must submit to the authority. An individual who ignores the officer’s request and walks away has not been seized for Fourth Amendment purposes. | a. Restraint of liberty; b. Intent to make an arrest; c. Comprehension by the detainee that he/she is under arrest. |

| Types (Student should complete these options) | ||||

| Legal Authority (Student should complete these options) | ||||

| Definition | An exploration of a person's body, property, or other private area conducted by a peace officer for supporting | Temporary restraint that prevents a person from walking or driving away. | Act or instance of taking possession of a person or property by legal right or process. | A seizure or forcible restraint by legal authority; Taking or keeping of a person in custody by legal authority |

b. General Warrant

The rule of the Fourth Amendment identifies how a peace officer should execute a search and/or seizure. The search and/or seizure must be done with a warrant according to the following requirements:

- probable cause;

- judge’s signature supported by

- oath or affirmation (typically an affidavit).

Wells Fargo Search Warrant and Affidavit[58]

According to the Fourth Amendment, searches can not be conducted without a warrant. This general rule is important as all agents must conduct the search according to a warrant unless an exception to a warranted search exists. Generally, warrants must be executed after agents knock-and-announce their presence. This rule serves in several capacities – namely to prevent loss of human life, to provide officer safety, protect a person’s precedential right to privacy and to protect said person from sudden and explosive intrusion in their homes.

c. No-Knock Warrant – Special Conditions Warrant

The history of the No-Knock Warrant began in Ker v. California (1963) where a law enforcement agent believed the petitioner was involved in the sale of marijuana and purchased marijuana from a known drug dealer.[59] Additionally, the prosecution noted that if the drug dealer was known to the agent, the law enforcement agent is then justified in conducting a search without a warrant.[60] The court examined the collection of the evidence based upon the reasonableness of the Fourth Amendment. The court further remarked that the law enforcement agent’s belief which developed prior to the search was founded upon the federal standard of relying upon the compliance of the state law.[61] In this instance, the state law was followed, while agents entered into the location quietly to protect officer’s from possible danger. Hence, the defendant was constitutionally subject to both a lawful arrest as well as a search incident to arrest which yielded constitutional evidence.[62] This incident followed President Richard Nixon’s commencing of his campaign slogan of the “war on drugs.”

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

President Richard Nixon vowed to tame the beast of drugs through the use of the No-Knock warrant. The increased use of No-Knock warrants was a product of the country’s “war on drugs,” a series of federal and local policies aimed at cracking down on recreational drug use. President Nixon launched the campaign in the 1970s, but it gained momentum in the 1980s under President Ronald Reagan.[63]

This controversial No-Knock warrant yielded many problems, then and now. In response to the current problems, some jurisdictions have passed legislation which bans and/or limits its use. Note: Federal law allows for No-Knock warrants for potential federal crimes, as explained earlier in this chapter. This exception to the execution of the general warrant rule continues to support its use by claiming that it protects the rights of the accused and supports officer safety. Increasing the use of the No-Knock warrant proved to be problematic with the rise of civilians being caught in the cross hairs.

In Richards v. Wisconsin (1997), Richards sought to clarify how the No-Knock Warrant was expanded from a personal dwelling to a motel room.[64] In this case, the Supreme Court found that the agent did not violate the Fourth Amendment. The court reviewed a No-Knock warrant for a hotel room whereby the verbiage supporting the No-Knock portion of the warrant was removed. Subsequently, the agents operated as if the warrant was a No-Knock warrant due to their thoughts of danger in the room. According to the court, “the police must have a reasonable suspicion that knocking and announcing their presence, under the particular circumstances, would be dangerous or futile, or that it would inhibit the effective investigation of the crime by, for example, allowing the destruction of evidence.”[65]

Breonna’s Law was the legislation created to limit No-Knock warrants in light of a fatal shooting of an unarmed Black woman, Breonna Taylor. Breonna endured an unwarranted attack in her home by the Louisville Police Department looking for the wrong suspect in the wrong home. The agents failed to knock and announce, but erroneously executed a No-Knock Warrant.[66] Ultimately, this legislation has ignited a call to action for all agencies who still support No-Knock Warrants. Unfortunately, every good initiative can turn sour. Opponents of this initial movement bought a domain page bearing Taylor’s name in an effort to support “good cops.”[67]

Mural of Breonna Taylor[68]

“Louisville’s Metro Council voted unanimously to pass Breonna’s Law. The bill was rightfully named in honor of Breonna Taylor, an award-winning EMT, essential worker, and daughter who worked tirelessly to help others and who was killed in her home by Louisville police officers… Breonna’s Law effectively outlaws “no-knock” warrants and requires body cameras to be turned on before and after every search.”[69]

d. Special Conditions Warrant

These are limited searches that the court considers reasonable because societal needs are thought to outweigh the individual’s normal expectation of privacy:

-

- Prison

- Probation and parole searches

- Drug testing for certain occupations

- Administrative searches of closely regulated businesses

- Community caretaking searches

- Public school searches[70]

Part V: Searches Without A Warrant

a. Consent

Consent is the number one exception to the warrant requirement. Consent is important in a warrantless search because it allows an unchecked, unrestricted access to the items or persons being searched. Consent is defined as “[a] voluntary yielding to what another proposes or desires; agreement, approval, or permission regarding some act or purpose, especially given voluntarily by a competent person; legally effective assent.”[71] Agents must be careful to meticulously document that the consent was relevant and voluntary. Consent is particularly appealing to law enforcement agents as it is approval without restrictions. Recall, warrants have restrictions and this makes consent appealing to law enforcement agents. On the other hand, consent may be revoked at any moment. This disadvantage makes consent unappealing to law enforcement agents. Therefore, consent is the best exception and the worst exception for warrantless searches.

b. Exigent-Circumstances Doctrine

Exigent-circumstances doctrine is another exception to the warrant requirement. This exception exists in specific situations which include maintaining safety of persons’ lives and imminent danger to persons from a suspect. Exigent-circumstances doctrine (or exigent circumstances) is defined as “[t]he rule that emergency conditions may justify a warrantless search and seizure, [especially] when there is probable cause to believe that evidence will be removed or destroyed before a warrant can be obtained.”[72] Exigent circumstances are also referred to as an emergency circumstance.

One such instance which explored exigent circumstances was pursuit of a misdemeanant. In Lange v. California (2021), as a result of the defendant’s writ of certiorari, the court reviewed a common application of exigent circumstances in an effort to provide guidance to all lower courts.[73] The defendant suggested that the court should examine this concept because most warrantless searches are predecessors to misdemeanor prosecutions. Specifically, the defendant wanted the court to address the following issue: “Does pursuit of a person who a police officer has probable cause to believe has committed a misdemeanor categorically qualify as an exigent circumstance sufficient to allow the officer to enter a home without a warrant?”[74]

In a unique opinion, SCOTUS held 9-0 that “[u]nder the Fourth Amendment, pursuit of a fleeing misdemeanor suspect does not always or categorically qualify as an exigent circumstance justifying a warrantless entry into a home.” Justice Kagan penned the opinion joined by Justice Thomas in part. Specifically, Justice Kagan wrote “[t]he Court has recognized exigent circumstances when an officer must act to prevent imminent injury, the destruction of evidence, or a felony suspect’s escape.”[75]

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

Exigent is defined as “[a] situation in which a police officer must take immediate action to effectively make an arrest, search, or seizure for which probable cause exists, and thus may do so without first obtaining a warrant.

Exigent circumstances may exist if

(1) a person’s life or safety is threatened,

(2) a suspect’s escape is imminent, or

(3) evidence is about to be removed or destroyed.”[76]

c. Plain View Doctrine

Additionally, plain view, sometimes referred to as plain sight, allows agents to search without a warrant. For reference, plain view/plain sight doctrine is defined as “The rule permitting a police officer’s warrantless seizure and use as evidence of an item seen in plain view from a lawful position or during a legal search when the officer has probable cause to believe that the item is evidence of a crime.”[77] According to the definition, the legal standard which must be met is probable cause. As a result, there are two ways to obtain evidence in this capacity. An agent may conduct a warrantless seizure if the evidence being confiscated is done through the agent’s own senses – touch, taste, smell, sight, or hearing. The law enforcement agent’s assessment of legal evidence through their five senses must be completed pursuant to a legal stance of the agent. In Maryland v. Macon (1985), the court noted an example of a plain view exception which the court held did not violate the defendant’s Fourth Amendment unreasonable search and seizure rights.[78] The court noted that the actions of the law enforcement agents were lawful.[79] Specifically, the court stated these lawful actions of entering the bookstore was open and intentional for all to see.[80] Further, this does not infringe on the defendant’s legitimate expectation of privacy preventing the legal finding of a reasonable search within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment.[81]

Equally important, the plain view/sight/feel doctrine is not without limitations. According to Minnesota v. Dickerson (1993), the court reviewed the actions of a law enforcement agent when he conducted a limited outer garment pat down search based upon the defendant’s vague actions, while exiting a known cocaine building.[82] The court determined that the warrantless search based upon reasonable suspicion remains limited to discovering weapons which may harm the officer or others.[83] Additionally, this limited or protective search may not supersede the boundaries of Terry v. Ohio (1968) which set the perimeters of all pat down searches.[84]

Finally, if the search supersedes these boundaries then a taint occurs. According to Black’s Law Dictionary, a taint is defined as “[t]o contaminate or corrupt [evidence].”[85] Additionally, this taint, also known as the original taint of the evidence is deemed inadmissible. According to Black’s Law Dictionary, inadmissible is defined as “(Of evidence) excludable by some rule of evidence.”[86] Furthermore, any additional evidence collected as a result of the first or original taint, is deemed inadmissible as well. However, a plain view/plain sight/plain feel exception may occur pursuant to a warranted seizure, only if the officer has probable cause to believe that a crime will or did occur.[87]

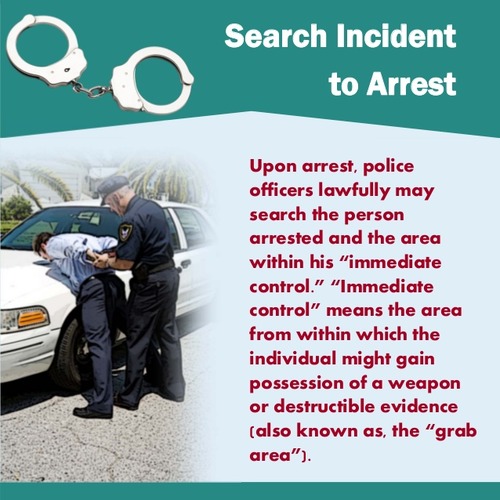

d. Search Incident to Lawful Arrest

Search incident to lawful arrest[88]

Search Incident To Lawful Arrest is “[a] warrantless search of a suspect’s person and immediate vicinity, no warrant being required because of the need to keep officers safe and to preserve evidence.”[89] Legal scholars differentiate between a search incident to lawful arrest and a protective search based upon its scope of search. Most scholars suggest that a search incident to arrest must remain in the immediate vicinity of the arrest. Remember, these arrests are limited as they are being conducted without a warrant.

Part VI: Applications of the Fourth Amendment

a. Use of Force

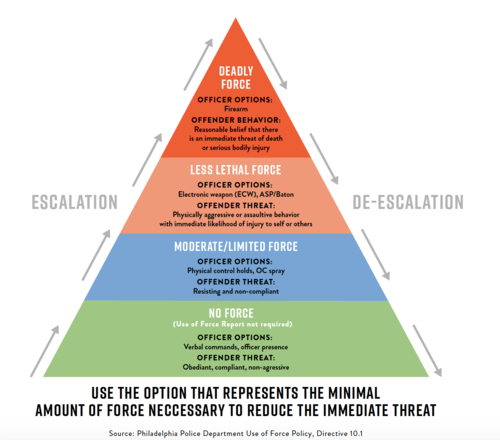

According to Black’s Law Dictionary, use of force is defined as “[t]he principle that a law-enforcement officer may legally resort to force, even deadly force, in the appropriate circumstances.”[90] Use of Force remains a controversial topic in law enforcement circles as agents weigh their views on reasonableness while present in the situation and the judicial, legislative, and executive branches all balance their perspective views regarding the situation. As noted many times over, there is no-single, go to definition for this term. In short, you will see this concept used in various ways. It is of utmost importance that those who read this section, do so with an eye toward the referenced definition.

When used in our text, we center use of force as a legal analysis which requires an independent neutral magistrate or arbiter to weigh the agent’s response to the suspect’s force. Specifically, the arbiter must assess whether the amount of the physical response by an agent is commiserate to the amount of force from the suspect? This analysis attempts to review the actions by the agent from every plausible side. Whereas, the International Association of the Chiefs of Police have agreed that use of force is defined as an “amount of effort required by police to compel compliance by an unwilling subject.”[91]

We must note that use of force embeds an escalating approach to compelling compliance. This approach is typically referred to as the use of force continuum and is widely referenced and adopted by most agencies. Importantly, for our purposes, agents should concentrate on de-escalation. De-escalation is defined as “tactics and technique actions used by officers, when safe and feasible without compromising law enforcement priorities, that seek to minimize the likelihood of the need to use force during an incident and increase the likelihood of voluntary compliance as much as possible.”[92] It is important that both suspect and agent return home safely. After all, a suspect is not a convicted felon, therefore, the suspect should be allowed to proceed through the criminal justice system where appropriate. Additionally, if a suspect becomes a convicted felon, this does not mean that one will or has been sentenced to death. Therefore, each suspect should live to have their proverbial “day in court,” determining their guilt or non-guilt. Agents are restricted via the law with how and when they can compel compliance, therefore we will explore these options after reviewing the use of force continuum.

b. De-escalation

De-Escalation and Escalation Continuum[93]

“1. When Safe, Feasible, and Without Compromising Law Enforcement Priorities, Officers Shall Use De-Escalation Tactics in Order to Reduce the Need for Force.

(a). Officers shall conduct a threat assessment so as not to precipitate an unnecessary, unreasonable, or disproportionate use of force by placing themselves or others in undue jeopardy.

(b). Team approaches to de-escalation are encouraged and should consider officer training and skill level, number of officers, and whether any officer has successfully established rapport with the subject. Where officers use a team approach to de-escalation, each individual officer’s obligation to de-escalate will be satisfied as long as the officer’s actions complement the overall approach.

(c). Selection of de-escalation options should be guided by the totality of the circumstances with the goal of attaining voluntary compliance; considerations include:

Communication

Using communication intended to gain voluntary compliance, such as:

− Verbal persuasion

− Advisements and warnings (including TASER spark display to explain/warn prior to TASER application), given in a calm and explanatory manner.

Exception: Warnings given as a threat of force are not considered part of de-escalation.

− Clear instructions

− Using verbal techniques, such as Listen and Explain with Equity and Dignity (LEED) to calm an agitated subject and promote rational decision making

− Avoiding language, such as taunting or insults, that could escalate the incident

Considering whether any lack of compliance is a deliberate attempt to resist rather than an inability to comply based on factors including, but not limited to:

− Medical conditions

− Mental impairment

− Developmental disability

− Physical limitation

− Language barrier

− Drug interaction

− Behavioral crisis

− Fear or anxiety

Time

Attempt to slow down or stabilize the situation so that more time, options and resources are available for incident resolution.

− Scene stabilization assists in transitioning incidents from dynamic to static by limiting access to unsecured areas, limiting mobility and preventing the introduction of non- involved community members

− Avoiding or minimizing physical confrontation, unless necessary (for example, to protect someone, or stop dangerous behavior)

− Calling extra resources or officers to assist, such as CIT or Less-Lethal Certified officers

Distance

Maximizing tactical advantage by increasing distance to allow for greater reaction time.

Shielding

Utilizing cover and concealment for tactical advantage, such as:

− Placing barriers between an uncooperative subject and officers

− Using natural barriers in the immediate environment”[94]

Reviewing More Use Of Force Analysis[95]

| Degree of Force | Methodization |

|---|---|

| Agent Presence - No force is used. Best option. | Mere presence works to diffuse a situation. Note: agent must present as professional and nonthreatening. |

| Agent Verbalization - Force is not-physical. | Continue nonthreatening manner in commands |

| Empty-Hand Control - Officers use bodily force to gain control of a situation. | Soft technique. Officers use grabs, holds and joint locks to restrain an individual. |

| Less-Lethal Methods - Officers use less-lethal technologies to gain control of a situation. | Blunt impact. Officers may use a baton or projectile to immobilize a combative person. |

| Lethal Force - Officers use lethal weapons to gain control of a situation. Should only be used if a suspect poses a serious threat to the officer or another individual. |

Officers use deadly weapons such as firearms to stop an individual's actions. |

Part VII: Violations of the Fourth Amendment

As law enforcement agents seek to use the Fourth Amendment, the guarantees of the amendment must be met. According to the verbiage of the Fourth Amendment, the rule requires law enforcement agents to obtain a warrant prior to a search. Of course, we have noted above that some exceptions exist to this rule; however, every action must include behavior free from unreasonable search and seizures as well as be supported by probable cause (unless conducting a limited search). Remember, probable cause must exist prior to a judge approving the warrant or the law enforcement agent conducting the search. Although these requirements remain constant, some agents knowingly or unknowingly engage in behavior adverse to the Fourth Amendment. In these instances, the defendant will file a motion to suppress the evidence. A motion to suppress is “[a] usu. pretrial motion to exclude evidence from a criminal trial; esp., a request that the court prohibit the introduction of illegally obtained evidence.”[96] When reviewing a motion to suppress, a judge will determine if:

- Police misconduct occurred (this requires evidence of the illegality of the law enforcement’s actions) and

- If such elements existed at the time of the agent’s actions.[97]

If both conditions are met, then the judge may grant the motion to suppress if and only if no other exceptions exist.

- If the judge denies the motion to suppress, then the evidence may be used during the trial.

- If the judge grants the motion to suppress, then the illegally or unconstitutionally obtained evidence can not be used during the trial.

It is important to note that a case may proceed without the illegally obtained evidence if additional evidence, testimony, and facts to sustain the charges. Otherwise, the defendant or their attorney may file a motion to dismiss the charges against the defendant. The motion to dismiss the case is “[a] request that the court dismiss the case because of settlement, voluntary withdrawal, or a procedural defect.”[98] In this case, the court would dismiss the charges according to a procedural defect. Essentially, the defendant attests that the prosecution can no longer sustain the charges against them and files a motion to dismiss. As a result, the judge will determine if the remaining elements support the current charges. Therefore, a violation of the Fourth Amendment has many ramifications and may impact the evidence before the court and any additional evidence which law enforcement agents obtained after the initial illegal evidence was obtained. The next section outlines in detail how this evidence may be in danger of suppression as well.

a. Exclusionary Rule

1. Determining if the Exclusionary Rule Applies

Prior to Weeks v. U.S. (1914), the courts did not address a formal sanction for illegally or unconstitutionally obtained evidence. In Weeks, the court noted that evidence collected from two unconstitutional warrantless searches should have been inadmissible in the trial court. In creating this new concept of the Exclusionary Rule, Justice William R. Day writing for the majority opinion in the landmark case of Weeks explained why these facts merited a departure from judicial support typically extended to law enforcement regarding the Fourth Amendment.[99] The Supreme Court decision in Mapp v. Ohio (1961) established that the exclusionary rule applied to evidence illegally obtained in violation of the Fourth Amendment.[100]

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

“If letters and private documents can thus be seized and held and used in evidence against a citizen accused of an offense, the protection of the Fourth Amendment, declaring his right to be secure against such searches and seizures, is of no value, and…might as well be stricken from the Constitution. The efforts of the courts and their officials to bring the guilty to punishment, praiseworthy as they are, are not to be aided by the sacrifice of those great principles established by years of endeavor and suffering which have resulted in…the fundamental law of the land.”[101]

For most college and law students (and even some attorneys), the exclusionary rule is a difficult concept to grasp as it requires several steps. A defendant files a motion and has the burden of proof to suppress the questionable evidence. Note: the is a shift in the burden of proof from the prosecutor which occurs in most other criminal hearings.

The judge will consider three factors in their analysis:

- Did police misconduct occur? There are many ways to show police misconduct. Two examples of police misconduct may be illegally obtained evidence without a warrant or obtaining evidence with a faulty warrant. At any rate, the exclusionary rule does not enter a legal analysis unless and until the trigger of police misconduct occurs.

- Once police misconduct occurs, then the judge must determine if probable cause exists?

- Finally, if probable cause exists, then the judge must determine if the defendant was searched illegally?[102]

If steps one through three are met, then “any evidence collected from the search may be excluded from evidence at trial.”[103] However, most significant to this analysis is that the inquiry does not end here.

Now, the burden of proof shifts to the prosecutor to provide an exception to the exclusionary rule which will deem the evidence admissible. If the prosecution proves that a legal exception to the exclusionary rule exists, then the motion to suppress will be granted and the evidence is deemed inadmissible. Comparatively, if the prosecution proves that a legal exception to the exclusionary rule exists, then the motion to suppress will be denied and the evidence is deemed admissible. Let’s review the five exceptions to the exclusionary rule and their differences.

2. Identifying the Exceptions to the Exclusionary Rule

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

Now that the judge has determined that the exclusionary rule is applicable, the next logical question that follows is – Does an exception to the Exclusionary rule exist?

IMPORTANT NOTE:

The analysis for the exclusionary rule does not end when we determine that it applies in a particular case. Once the judge determines the exclusionary rule applies, then the judge must ask if any exceptions exist. There are five exceptions which may be analyzed in response to the exclusionary rule being triggered. The first exception is the Attenuation Doctrine. Attenuation Doctrine is defined as “[a] rule that excludes or suppresses evidence obtained in violation of an accused person’s constitutional rights. The rule providing that evidence obtained by illegal means may nonetheless be admissible if the connection between the evidence and the illegal means is sufficiently remote.”[104]

The Attenuation Doctrine was first identified in Nardone v. U.S. (1939) when the government used indirect evidence of illegal wiretapping. The court held that a “[s]ophisticated argument may prove a causal connection between information obtained through illicit wiretapping and the Government’s proof. As a matter of good sense, however, such connection may have become so attenuated as to dissipate the taint.”[105]

The Supreme Court revisited and reintroduced the Attenuation Doctrine in Wong Son (1963) when the court held that the governmental agent’s unlawful entry of the first defendant’s home tainted any subsequent statements made by the defendant.[106] Thus, the court deems evidence admissible when the connection between the police misconduct is weak “or has been interrupted by an intervening circumstance so that the violation is not served by suppression.”[107]

In determining if the attenuation rises to the level of a valid exception, the court in Brown v. Illinois (1975) notes three relevant factors:

- The amount of time between the unconstitutional conduct and the discovery of evidence. Generally the closer in time the more likely the evidence will likely be suppressed.

- The presence of intervening circumstances. Here, the intervening circumstance was the discovery of the valid arrest warrant.

- The court evaluates the purpose and flagrancy of the official misconduct. The more flagrant the misconduct the more it needs to be deterred. Negligence, errors in judgment etc., are not enough. Systemic or recurrent police misconduct is required.[108]

Thus, Attenuation Doctrine may apply if the exclusionary rule is triggered and the three relevant factors are met. If this analysis occurs and the attenuation doctrine applies, then the evidence is deemed admissible.

Another exception to the exclusionary rule is the Inevitable Discovery Doctrine. This rule is defined when the “… evidence obtained indirectly from an illegal search is admissible, and the illegality of the search is harmless, if the evidence would have been obtained nevertheless in the ordinary course of police work.”[109] This exception was first noted in Nix v. Williams (1984) when the court held that the defendant’s statement, identifying where the body of his victim was located, was obtained illegally.[110] The court supported its holding with the Inevitable Discovery Doctrine as “the discovery and condition of the victim’s body was properly admitted at respondent’s second trial on the ground that it would ultimately or inevitably have been discovered even if no violation of any constitutional provision had taken place.”[111] It is important to note that the burden shifts to the prosecution to establish “by a preponderance of evidence that the information ultimately or inevitably would have been discovered by lawful means.”[112] The sole purpose of the exclusionary rule is to address police misconduct, but if the evidence is discovered regardless of the misconduct then it should be admissible. Therefore, the evidence obtained by illegal means is admissible, if a legal means of obtaining the evidence is available.

Next, we examine Independent Source Doctrine as an exception to the Exclusionary Rule. This Doctrine allows evidence illegally obtained to be admitted, if the evidence could be obtained by an autonomous line of investigation. The Independent Source Doctrine is defined as “…[t]he rule providing — as an exception to the fruit-of-the-poisonous-tree doctrine — that evidence obtained by illegal means may nonetheless be admissible if that evidence is also obtained by legal means unrelated to the original illegal conduct.”[113] The court in Murray v. United States (1988) and Nix v. Williams (1984) emphasized that evidence illegally obtained can be determined clean if it would have been discovered in the same condition anyway through legal means not related to the original illegal source.[114] Similar to the Inevitable Discovery Doctrine, the burden of proof shifts to the prosecution to establish the valid Independent Source of the evidence. To this end, the evidence would be admissible if the Independent Source Doctrine is applied.

Additionally, the Good Faith Doctrine is an exception to the exclusionary rule. It states that “…evidence obtained under a warrant later found to be invalid (especially because it is not supported by probable cause) is nonetheless admissible if the police reasonably relied on the notion that the warrant was valid.”[115] The Supreme Court upheld law enforcement agent’s illegal seizure of a large quantity of drugs based upon the agent’s belief that the warrant was sufficient in U.S. v. Leon (1984).[116] Although the court determined that the warrant was insufficient for the seizure, the court indicated in its analysis that the exclusionary rule should be weighed in circumstances where law enforcement agent’s do not exhibit bad behavior, but instead really act in good faith.[117] Accordingly, evidence is admissible if the Good Faith Doctrine is applied to law enforcement’s reliance on a legal statute later deemed invalid.

Finally, the Harmless Error Doctrine is noted as an exception to the exclusionary rule. Harmless Error Rule is defined as “[t]he doctrine that an unimportant mistake by a trial judge, or some minor irregularity at trial, will not result in a reversal on appeal.”[118] The Harmless Error Doctrine is distinguished from all other exceptions as it addresses mistakes by trial judges, whereas the other exceptions address mistakes raised by law enforcement agents. Of all of the exceptions to the Exclusionary Rule mentioned above, Epps posits that defendants raise the Harmless Error Doctrine more than any other exception.[119] Unfortunately, courts continue to acknowledge a lack of continuity within the test or approach for harmless error. According to Epps, Chapman (1967) reminds us that harmless error is a difficult concept for the courts’ to navigate as the automatic reversal test does not apply to all harmless error cases.[120] Additionally, harmless error is dubbed a mystery as the process remains elusive. Judicially created, harmless error integrates the necessary Constitutional protections in the criminal trial procedure as well as adverse policies that underpin criminal statutes. Harmless error appears to be more palatable because of its intentional flexibility. Courts continue to struggle with implementation as a consensus surrounding standard of application remains. Therefore, Pondolfi notes courts should engage in a specific analysis which includes examining their explicit Constitutional support, legislative reinforcement, and historical weight.[121] As a result, evidence is admissible if the Harmless Error Doctrine is applied to specific cases. These cases mistakenly allowed the jury to hear prejudicial testimony, then attempt to correct the record by striking the same testimony, while ordering the jury to ignore the same testimony.

Although the analysis of police misconduct spans the Exclusionary Rule, the five exceptions (Attenuation, Independent Source, Inevitable Discovery, Good Faith, and Harmless Error) dictate that one additional aspect should be examined. After a motion to suppress is denied, illegal evidence is deemed inadmissible. Furthermore, all evidence which followed the initial illegal evidence is inadmissible as well. In fact, this legal concept is referred to as fruit of the poisonous tree.

b. Exclusionary Rule and the Fruit of the Poisonous Tree

Exclusionary Rule and Fruit of the Poisonous Tree[122]

As we close the loop in the analysis of the Exclusionary Rule, the understanding of the exceptions and the admissibility of any evidence obtained as a result of the illegal search requires examination of one additional doctrine. Most constitutional scholars agree that fruit of the poisonous tree is a legal extension of the Exclusionary Rule.

The Fruit of the Poisonous Tree as a legal concept was first applied in Silverthorne v. U.S. (1920), when the court noted that the “Fourth Amendment protects a corporation and its officers from compulsory production of the corporate books and papers for use in a criminal proceeding against them when the information upon which the subpoenas were framed was derived by the Government through a previous unconstitutional search and seizure.”[123]

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

Fruit of the Poisonous Tree Doctrine is defined as “[t]he rule that evidence derived from an illegal search, arrest, or interrogation is inadmissible because the evidence (the “fruit”) was tainted by the illegality (the ‘poisonous tree’).”[125] Similar to the exclusionary rule, fruit of the poisonous tree must follow the analysis regarding exceptions. If a defendant alleges the evidence is subject to the fruit of the poisonous tree, then the evidence will be admissible if the independent source, inevitable discovery, attenuation, good faith and/or harmless error applies. Under this doctrine, if the defendant’s drugs are located as a result of an unreasonable search and seizure of his car, the the drugs seized are also inadmissible as the drugs were the “fruit” (direct extension) of the original tainted search.

It is worth noting that if police misconduct occurs, a defendant is not automatically entitled to relief or remedy against a law enforcement agent. Normally, these actions are protected by qualified immunity. Qualified immunity is defined as “[i]mmunity from civil liability for a public official who is performing a discretionary function, as long as the conduct does not violate clearly established constitutional or statutory rights.”[126]

Part VII: Bringing the Fourth Amendment into the Digital Age

Cellular device

Supreme Court brings Fourth Amendment into the Digital Age with Cell Phone Ruling[128]

Recall the discussion from earlier in this chapter, explaining the Supreme Court’s holding in Chimel v. California (1969) where the items used were unconstitutionally obtained due to the lack of consent obtained “on the basis of the lawful arrest.”[129] In Riley v. California (2014), the Supreme Court brought the Fourth Amendment into the digital age, holding that the warrantless search exception following an arrest exists for the purposes of protecting officer safety and preserving evidence, neither of which is at issue in the search of digital data.[130] Chief Justice Roberts, writing for a unanimous Court, characterized cell phones as minicomputers with massive amounts of private information, which distinguished them from other personal items such as a wallet or purse.[131] Therefore, “[t]he Riley court established a rare bright-line rule under the Fourth Amendment when it declared that data searches of cell phones – regardless of type – are unlawful incident to arrest.“[132]

Additionally, the court examined other important data for cell phone usage. In Carpenter v. United States (2018), the court discussed the 12,898 location points obtained from the petitioner, Timothy Carpenter’s phone.[133] In this case, the court established a position on significant performance and functioning cell phone data which is gathered from cell sites. When this information is generated the cell site captures it, stores it and generates a time-stamped record known as cell-site location information (CSLI).[134] Thus the question before the court “…whether the Government conducts a search under the Fourth Amendment when it accesses historical cell phone records that provide a comprehensive chronicle of the user’s past movements.”[135] First and foremost, the court noted that “[t]he government’s acquisition of Timothy Carpenter’s cell-site records from his wireless carriers was a Fourth Amendment search.[136] [Second], the government did not obtain a warrant supported by probable cause before acquiring those records.” [137] The court reminded law enforcement agent’s that they have this new highly scientific tool to assist in investigations, but the court declined “to grant the state unrestricted access to a wireless carrier’s database of physical location information [to accomplish these goals].”[138] Thus, the Fourth Amendment’s application was further expanded by the Supreme Court of the United States.

Critical Reflections:

- Analyze whether checks such as the exclusionary rule and other doctrines leveraged by the courts have balanced unlawful search and seizures by police/government agents. Why or why not?

- As a result of the wrongful deaths and/or “incidents” that have occurred in the last 10 years, the concept of No Knock warrants are being revisited by the courts. Will legislatures introduce changes to improve the execution of this warrant? Why or why not?

- Explain any challenges/changes there could be in the Use of Force Continuum and De-escalation over the next 10 years given today’s policing climate. Illustrate how all stakeholders may be affected.

- Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1, 16 (1968). ↵

- Unreasonable search and seizure. (n.d.). LII / Legal Information Institute. https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/unreasonable_search_and_seizure#:~:text=An%20unreasonable%20search%20and%20seizure,has%20criminal%20evidence%20or%203). ↵

- Fourth Amendment activities. (n.d.). United States Courts. https://www.uscourts.gov/about-federal-courts/educational-resources/educational-activities/fourth-amendment-activities ↵

- AGENT, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- United States Congress. (n.d.). Fourth amendment: Historical background | constitution annotated | congress.gov | library of Congress. Constitution Annotated. Retrieved April 10, 2021, from https://constitution.congress.gov/browse/essay/amdt4_1 ↵

- 5 Coke's Repts. 91a, 77 Eng. Rep. 194 (K.B. 1604). ↵

- Fourth amendment, 2021. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Steinberg, D. (2008). The uses and misuses of the fourth amendment history. Journal of Constitutional Law, 10(3), 581–606. https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1212&context=jcl ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Cass v. State, 124 Tex. Crim. 208, 61 S.W.2d 500 (1933). ↵

- Fourth Amendment. (n.d.). LII / Legal Information Institute. https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/fourth_amendment#:~:text=Reasonableness%20Requirement,of%20a%20search%20or%20seizure. ↵

- United States v. Knights, 534 U.S. 112 (2001). ↵

- Wyoming v. Houghton, 526 U.S. 205, 300 (1999). ↵

- Introduction to 4th search and seizure Arkansas. (n.d.). https://www.slideshare.net/ClaySmith37/introduction-to-4th-search-and-seizure-arkansas ↵

- O'Connor v. Ortega, 480 U.S. 709 (1987). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 (1968). ↵

- Id. at 22. ↵

- STOP-AND-FRISK, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- STOP-AND-FRISK, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- LibGuides: Verde, Brandon: Introduction. (n.d.). https://avemarialaw.libguides.com/CriminalProcedure ↵

- Id. ↵

- BRIGHT-LINE RULE, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- 412 U.S. 218 (1973). ↵

- {{meta.pageTitle}}. (n.d.-b). {{Meta.siteName}}. https://www.oyez.org/cases/1972/71-732. ↵

- Ohio v. Robinette, 519 U.S. 33, 39 (1996). ↵

- TOTALITY-OF-THE-CIRCUMSTANCES TEST, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- case-by-case. (2023). https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/case-by-case. ↵

- Steinberg, 2008. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- WARRANT, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Locke v. United States, 11 U.S. 339 (1813). ↵

- Brinegar v. United States, 338 U.S. 160, 176 (1949). ↵

- PROBABLE CAUSE, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Brinegar v. United States, 1949. ↵

- EVIDENCE, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- EXCEPTION, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Federal Bureau of Investigation team members demonstrate an execution of a search warrant. Public domain. https://nara.getarchive.net/media/federal-bureau-of-investigation-team-members-demonstrate-dec655 ↵

- Wilson v. Layne, 526 U.S. 603 (199). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- United States v. Ramirez, 523 U.S. 65 (1998). ↵

- United States v. Banks, 540 U.S. 31 (2003). ↵

- Fryling, T. M. F. (2023). Constitutional law in criminal justice. Aspen Publishing, p. 131-134. ↵

- Chimel v. California, 395 U.S. 752 (1969). ↵

- Id. at 755-768. ↵

- 392 U.S. 1 (1968). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Wells Fargo Search warrant and affidavit. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/10/20/business/dealbook/document-Wells-Fargo-Search-Warrant-and-Affidavit.html ↵

- Ker v. California, 374 U.S. 23 (1963). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Norwood, C. (2020, June 12). The war on drugs gave rise to ‘No-Knock’ warrants. Breonna Taylor’s death could end them. PBS NewsHour. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/the-war-on-drugs-gave-rise-to-no-knock-warrants-breonna-taylors-death-could-end-them ↵

- Richards v. Wisconsin, 117 S. Ct. 1416 (1997). ↵

- Id. at 1421. ↵

- Brown, M., & Duvall, T. (2020, June 30). Fact check: Louisville police had a “no-knock” warrant for Breonna Taylor’s apartment. USA TODAY. https://eu.usatoday.com/story/news/factcheck/2020/06/30/fact-check-police-had-no-knock-warrant-breonna-taylor-apartment/3235029001/ ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Faircloth, Terence. Breonna Taylor, mural by HIERO. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. Flickr. ↵

- UPDATED! Quick signature: Justice for Breonna Taylor! (2021, February 1). MomsRising. https://www.momsrising.org/blog/updated-quick-signature-justice-for-breonna-taylor ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- CONSENT, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- EXIGENT-CIRCUMSTANCES DOCTRINE, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Lange v. California, 594 US _ (2021). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Lange v. California. (n.d.). Oyez. Retrieved August 27, 2023, from https://www.oyez.org/cases/2020/20-18. ↵

- EXIGENT CIRCUMSTANCES, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- PLAIN-VIEW DOCTRINE, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Maryland v. Macon, 472 U.S. 463 (1985). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Minnesota v. Dickerson, 508 U.S. 366 (1993). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- TAINT, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- INADMISSIBLE, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Criminal justice 4th and 5th amendments. (n.d.). [Slide show]. https://quizlet.com/395124418/criminal-justice-4th-5th-amendments-flash-cards/ ↵

- SEARCH INCIDENT TO ARREST, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- USE-OF-FORCE DOCTRINE, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- International Association of the Chiefs of Police (2001). Police Use of Force in America. Alexandria, Virginia. ↵

- The call for de-escalation training. (n.d.). [Slide show; Power point slides]. IACP. https://www.theiacp.org/sites/default/files/Engel_Use%20of%20Force%20and%20De-escalation_FINAL.pdf ↵

- International Association of the Chiefs of Police (2001). ↵

- 8.100 - De-Escalation - police manual | seattle.gov. (n.d.). Seattle Police Department Manual. Retrieved May 14, 2021, from https://www.seattle.gov/police-manual/title-8---use-of-force/8100---de-escalation ↵

- International Association of the Chiefs of Police (2001). ↵

- MOTION TO SUPPRESS, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- MOTION TO DISMISS, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 20249). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961). ↵

- Weeks v. U.S. (1914). ↵

- Mapp v. Ohio (1961). ↵

- Id. ↵

- ATTENUATION DOCTRINE, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Nardone v. United States, 308 U.S. 338, 341 (1939). ↵

- Wong Sun v. United States, 371 U.S. 471 (1963). ↵

- Utah v. Strieff, 136 S.Ct. 2056 (2016). ↵

- Brown v. Illinois, 422 U.S. 590 (1975). ↵

- INEVITABLE DISCOVERY RULE, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Nix v. Williams, 467 U.S. 440 (1984). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- INDEPENDENT SOURCE DOCTRINE, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Murray v. U.S., 487 U.S. 533 (1988); Nix v. Williams, 467 U.s. 431 (1984). ↵

- GOOD FAITH DOCTRINE, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- U.S. v. Leon, 468 U.S. 897 (1984). ↵

- Id. ↵

- HARMLESS ERROR RULE, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Epps, D. (2018, June). Harmless errors and substantial rights. Harvard Law Review. https://harvardlawreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/2117-2186_Online.pdf ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Pondolfi, R. (1974). Principles for application of the harmless error standard. The University of Chicago Law Review, 616–634. https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3816&context=uclrev ↵

- The exclusionary rule. (n.d.). https://lawshelf.com/coursewarecontentview/the-exclusionary-rule ↵

- Silverthorne v. U.S., 231 U.S. 385 (1920). ↵

- Nardone v. United States, 308 U.S. 338, 341 (1939). ↵

- FRUIT OF THE POISONOUS TREE DOCTRINE, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- QUALIFIED IMMUNITY, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- History and scope of the amendment. (n.d.). LII / Legal Information Institute. Retrieved November 14, 2020, from https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution-conan/amendment-4/history-and-scope-of-the-amendment ↵

- Supreme Court brings Fourth Amendment into the Digital Age with Cell. (2016, January 27). Joseph Greenwald & Laake, PA. https://www.jgllaw.com/blog/supreme-court-brings-fourth-amendment-digital-age-cell-phone-ruling ↵

- Chimel v. California, 395 U.S. 752 (1969). ↵

- Riley v. California, 573 U.S. 373 (2014). ↵

- Id. ↵

- The U.S. Supreme Court says ‘No’ to Cell-Phone searches Incident to arrest | Illinois State Bar Association. (n.d.). ISBA IBJ. https://www.isba.org/ibj/2014/09/ussupremecourtsaysnocell-phonesea ↵

- Carpenter v. United States, 585 U.S. ___ (2018). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Howard, K. (2023, August 7). Carpenter v. United States - SCOTUSblog. SCOTUSblog. https://www.scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/carpenter-v-united-states-2/ ↵

- Carpenter v. United States, 2018. ↵