Chapter 6 – Amendment V: Indictment, Double Jeopardy, Due Process, Self-Incrimination & Just Compensation

Amendment V

Richard J. Forst and Tauya R. Forst

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

6.1 Identify the unfamiliar terms of the Fifth Amendment.

6.2 Summarize the differences between a right and a privilege.

6.3 Summarize each method in which a criminal can be charged with respect to the Fifth Amendment.

6.4 Describe what element(s) must be present for double jeopardy to occur.

6.5 Explain when double jeopardy attaches in a bench or jury trial.

6.6 Explain when the Miranda warning should be delivered.

6.7 Compare the differences between substantive and procedural due process.

6.8 Determine which factors are utilized to decide if a taking or regulation transpired.

6.9 Explain which entity or entities acted to limit the powers of the federal government’s taking abilities and by which measures.

KEY TERMS

| Double Jeopardy Clause | No Bill |

| Due Process | Offense |

| Eminent Domain | Presentment |

| Grand Jury | Public Use |

| Indictment | Privilege |

| Information | Rules of Evidence |

| Invoke | Taking |

| Just Compensation | True Bill |

| Miranda Warning | Waiver |

Amendment V

Passed by Congress September 25, 1789. Ratified December 15, 1791. The first 10 amendments form the Bill of Rights.

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.

United States Courts word cloud[1]

INTRODUCTION TO AMENDMENT V

Named amongst the Bill of Rights, Amendment V shares a similar historical foundation as the other nine amendments. It provides notable protections as well as the framework for the Miranda Warnings. The basis of its approach is traced to both the Fifteenth and Sixteenth centuries which proved to be an ambiguous, legal timeframe. However, it is clear that the emergence of certain newly allowed legal procedures supported by the Crown were contrary to the customary traditional law.[2] While this internal battle of justice and the law continue to unfold, jurists began openly identifying blatant disregards for justice as it related to the codified law. Furthermore, one of the most influential portions of the Fifth Amendment, the privilege against self-incrimination, began and ended with a revolution. Originally, the revolution involved religion, but later the revolution concluded with the state question.[3] Specifically, different sects of the Protestants battled other groups regarding the privilege against self-incrimination. These battles brewed between the Anglicans & Calvinists or the Crown & the Parliament. Thus, the privilege exists today within the American system due to England’s shift in faith to Anglican in the Sixteenth century as well as the Calvinists who became involved in the battle of injustices.[4] Therefore, the Fifth Amendment in America reveals five key components.

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT V

Part I: Right to Presentment or Grand Jury Indictment

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger;

Grand Jury Indictments[5]

This section frames how a criminal case begins which takes into account two variables:

- Whether the crime involved a violation of state or federal laws; and

- The seriousness of the crime is (i.e., felony vs. misdemeanor or other category of crime).

When prosecutors examine a case, there are many options available to them to proceed with criminal charges. One option is a grand jury defined as “[a] body of ([usually] 16 to 23) people who are chosen to sit permanently for at least a month — and sometimes a year — and who, in ex parte proceedings, decide whether to issue indictments.”[6] One may believe that every case begins with a grand jury. In fact, this is untrue. Cases may begin through information, presentment, a grand jury indictment and/or complaint of witness. According to Black’s Law Dictionary, information “is a formal criminal charge made by a prosecutor without a grand-jury indictment.”[7] Whereas, an information, also known as a bill of information, is prevalent when prosecutors charge defendants with misdemeanors. Ironically, some states allow prosecutors the use of information as a charging mechanism in felonies, as well. Each state provides their own policy and process when charging defendants.

In some rare instances, states allow presentment as a charging mechanism. A presentment “is a formal written accusation returned by a grand jury on its own initiative, without a prosecutor’s previous indictment request.”[8] Recall, a presentment is an outdated legal tool; however, some prosecutors are allowed to use presentments to help toll the statute of limitations on a case. The justices in State v. Baker (2018) emphasized the timing and prosecutor’s inability to circumvent proper jurisdiction as a means to obtaining charges and/or indictments.[9] Presentment is primarily a process of the past by which individuals of the grand jury “initiated an independent investigation and asked that a charge be drawn to cover the facts should they constitute a crime.”[10] However, this process is rarely used now due to the attorneys’ ability to provide expertise and direction to grand juries.

Another process important to charging an individual is an indictment. Indictments are conducted by grand juries. Grand juries and petit juries differ, but are routinely used interchangeably.

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

Grand juries typically contain 16-23 members, not to be confused with petit or trial jury which typically contains 6-12 members.

Grand juries provide a very unique perspective to the criminal justice system. Their purpose is to provide an unbiased approach to the charging of individuals after hearing the most compelling evidence from the prosecutor. In 99% of jurisdictions, the defendant is not present and unable to speak in the grand jury proceeding; however, some states allow the defendant to testify. The grand jury has become a fast favorite of prosecutors. Although prosecutors have options for charging defendants, many prosecutors chose the grand jury process to obtain a true bill for criminal charges instead of a preliminary hearing. During this process, prosecutors present their case without any information from the defense. Critics note that the grand jury process tends to negatively bias the defendant. At first blush this concept seems unfair, until one remembers the purpose of the grand jury. The grand jury process reviews whether the prosecutor possesses enough evidence to criminally charge a defendant; as opposed to finding a defendant guilty or not guilty of a crime. Depending upon the jurisdiction, the grand jury requires either a 2/3 or 3/4 agreement for an indictment.[11] If the grand jury believes enough evidence exists, then they deliver a “true bill.” The standard for delivering a true bill differs from state to state and jurisdiction to jurisdiction.

According to the American Law and Legal Library, ‘”In many states the grand jury is directed to indict only if the evidence before it establishes probable cause to believe that the accused committed the felony charged; in other [states], [the grand jury] is directed to indict “when all the evidence taken together, if unexplained or uncontradicted, would warrant a conviction of the defendant.”‘[12]

The true bill or an indictment for the defendant allows prosecutors to provide “formal written accusation of a crime, made by a grand jury and presented to a court for prosecution against the accused person.”[13]

On the other hand, what occurs if the grand jury determines the evidence does not support a true bill? If the grand jury determines the evidence does not support a true bill, then a “no bill” is delivered as the evidence is insufficient to hold a defendant accountable for the crime. A no bill: is “[a] grand jury’s notation that insufficient evidence exists for an indictment on a criminal charge.”[14]

True Bill v. No Bill[15]In this instance, the secrecy of the grand jury is of utmost importance to protect the identity of those who will never see criminal charges. In this way, critics of the grand jury note that the grand jury has become a mere technicality lacking true authority of its own. Furthermore, they state that the grand jury will side with prosecutor’s as a rubber stamp of justice.On August 1, 2023, a special prosecutor issued a historical indictment for former President Donald J. Trump. Read both indictments here[16] What stands out to you about the indictment as it relates to Amendment V? What requirements are addressed in the indictment itself?

Finally, a Prosecutor may issue a complaint or a criminal complaint defined as “[a] formal charging instrument by which a person is accused of a crime, usu. a misdemeanor or violation in a sworn statement.”[17] The complaint is typically weighted and presented from the perspective of a law enforcement agent. In fact, “[c]riminal complaints are typically filed by the prosecutor in cooperation with the police officer(s) who made the arrest.” According to Legal Match, the victim of a crime will individually file a criminal complaint against a suspect in some instances.[18] Additionally, this right contains an exception to the rule.[19] Remember, the Constitution includes the following verbiage “…except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the militia, when in actual service in time of war or public danger;”[20]

The Framers made a definitive point to address how a case should proceed, but created a caveat or exception. The language “except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the militia, when in actual service in time of war or public danger” speaks to exactly when the rule of the right to presentment or grand jury indictment should be applied and when other rules will apply. Finally, the Framers noted that this right applies to all military members or the militia (Air Force, Army, Marines or Navy, National Guard as well as Reserves).

Part II: Right Against Double Jeopardy

Right Against Double Jeopardy[21]

This section of the Fifth Amendment is widely quoted, erroneously applied, and continuously referenced. The right against double jeopardy is an important foundation of the criminal justice process; however, it is rarely applied correctly. In fact the double jeopardy clause is evidenced in the Fifth Amendment. However, the double jeopardy clause “does not prevent postacquittal appeals by the government if those appeals could not result in the defendant’s being subjected to a second trial for substantially the same offense before a second fact-trier. See U.S. v. Wilson, 420 U. S. 332…(1975).” Here the Constitution refers to the term offence. Significantly, the term offence means and it is interchangeable with the term offense. Most scholars note there is no definitional difference between these two terms; however, there is, in fact, a dialectal difference.[22] Offence is primarily used with British audiences, where the term offense is better suited for American audiences.[23] Black’s Law acknowledges that “[t]he terms ‘crime,’ ‘offense,’ and ‘criminal offense’ are all said to be synonymous, and ordinarily used interchangeably.”[24] Thus, when an individual engages in an alleged offense, they are against a law, ordinance, or statute. Let’s continue our analysis of the language of this section of Amendment V, by discussing the term jeopardy.

The term jeopardy is often disregarded or defined incorrectly. Black’s defines jeopardy as “the risk of conviction and punishment that a criminal defendant faces at trial.”[25] Again it is important to use Black’s Law Dictionary to define legal terms, as one will see this does not meet the lay definition of jeopardy. Jeopardy according to this section, underscores one’s ability to be convicted and penalized for an offense.[26] How and/or when does double jeopardy attach, preventing the defendant from being tried twice for the same offense? Let’s continue our analysis of a possible conviction with examining its affect on a bench trial versus a jury trial. In a jury trial, double jeopardy occurs once the jury is empaneled, whereas in a bench trial jeopardy attaches after the first witness is sworn.[27] According to Downum v. United States (1963) and Crist v. Bretz (1978), the court confirmed the Constitutional guarantee against being tried twice for a crime.[28] Both courts note that the defendant’s right attaches when the jury is empaneled and given the oath for the second trial.[29] Finally, there are few exceptions to this right against double jeopardy. Acquittal through fraud or retrial in a court where the court lacked jurisdiction are exceptions as well. Finally, Martinez v. Illinois (2014) supported the expansion of right against double jeopardy rule as it applied to all courts – both federal and state courts.[30]

“The Illinois Supreme Court’s error was consequential, for it introduced confusion into what we have consistently treated as a bright-line rule: A jury trial begins, and jeopardy attaches, when the jury is sworn.”[31]

Part III: Privilege Against Self-Incrimination

nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself,

Self-Incrimination[33]

Prior to this clause we have only reviewed and identified freedoms and rights as contained in the United States Constitution. Each word holds significant and unique meaning; hence, identifying something as a freedom or a right provides a completely different meaning to the clause. In this section, we will review a privilege. According to Black’s a privilege “grants someone the legal freedom to do or not to do a given act. {Privilege} immunizes conduct that, under ordinary circumstances, would subject the actor to liability.”[34]

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

Simply stated, a privilege provides legal justification as to why an individual will not be required to engage in an action.

Furthermore, a privilege within a legal realm may also coincide with the rules of evidence. According to Black’s Law Dictionary, it defines Rules of Evidence as “[t]he body of law regulating the admissibility of what is offered as proof into the record of a legal proceeding.”[35] Rules of Evidence provide parameters as to what is appropriately admitted in court. In fact, privileged information is not subject to disclosure or discovery due to the nature of its content. According to Cornell Law “…privileges exist not because of a fear that information provided will be inaccurate, but because there are public policy reasons that the information should not be disclosed.”[36] Some common examples of privilege are attorney-client privilege, clergy privilege, spousal privilege, and of course privilege against self-incrimination.

What privilege is guaranteed in this section of the Fifth Amendment? The privilege against self-incrimination or more commonly known as I plead the Fifth. Black’s defines self-incrimination as “[t]he act of indicating one’s own involvement in a crime or exposing oneself to prosecution, especially by making a statement.[37] Black’s Law Dictionary seeks to remind actors and those who may use this privilege that it is not absolute in its execution as the information, if obtained with a third party present, is not privileged. If this does not occur, then the privilege against self-incrimination operates as “an evidentiary rule that gives a witness the option to not disclose the fact asked for, even though it might be relevant.”[38] The privilege may be waived under certain conditions, but the general policy surrounding the privilege must be regarded. Waiving a privilege requires a full disclosure by the entity seeking to obtain information. Waiving a privilege entails one abandoning, renouncing or surrendering a privilege that one was technically entitled to exercise.[39]

No entity or governmental agent may compel a witness to provide evidence, testimony or information which may culminate in criminal prosecution.[40] Furthermore, defendant’s can not be penalized if they chose to waive this privilege. Operationally, the prosecutor and law enforcement agents should methodically build their cases with valid evidence regardless of the defendant making statements against one’s self. Finally, the privilege against self-incrimination only applies to testimony and/or verbal answers to questioning or grand jury requests.[41]

Therefore, a defendant can not invoke the privilege against self-incrimination if asked to produce hair samples, handwriting samples, or voice recordings.

The right against self-incrimination extends to civil, administrative, and grand jury proceedings if raised by a defendant or prospective defendant. Further, if there is an increased interest in the investigating agents for criminal activity, then this amendment and its clause would apply under the criminal activity investigation as well. An example of instances in civil incidents where defendants have a right against self-incrimination are connections to tax documents and discussion related to the tax documents.

How does the privilege against self-incrimination impact a defendants’ confessions? Miranda warnings are foundational to the discussion of a defendant’s confession under the privilege against self-incrimination. Providing a suspect with Miranda warnings is very important and should occur at pivotal times during the criminal process, but must occur when custodial interrogation occurs.[42]

In contrast, how does the privilege against self-incrimination impact defendant’s confessions outside of Miranda warnings? First, the authors acknowledge that the court does review confessions made outside of the Miranda warnings. This review is based upon the totality of the circumstances test. As previously discussed, the totality of the circumstances test includes a comprehensive approach for the entire situation which helps determine if the confession fulfills the voluntary and admissible or involuntary and inadmissible.

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

a. Suspect vulnerabilities (age, health, intelligence quotient (IQ), impact of videotaping, valid Miranda warnings),

b. Interrogating factors (duration of interrogation),

c. Place of questioning,

d. Use of deception (lies, processes, threats, and trickery), and

e. Promises[43]

Thus, most cases speak directly to critics surrounding confessions subject to privilege against self-incrimination requiring a complete and anticipatory argument if intended for use. Additionally, Marcus warns “[m]any judges allow confessions into evidence in cases in which police interrogators lied and threatened defendants or played on the mental, emotional, or physical weaknesses of suspects” once the actions are reviewed in terms of totality of the circumstances as listed above.[44]

Part IV: Right to Due Process

nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.

You Get Due Process[45]

You Get Due Process[45]

The Framers of the United States Constitution used specific language to indicate that individuals on American soil are entitled to a procedure which allows a just and fair hearing prior to governmental entities attempting to take anyone’s life (death eligibility), liberty (jail, prison, parole, and to some extent probation sentencing), or property (personal and real). This procedure is identified as due process of the law. What is due process? Black’s defines due process as “the conduct of legal proceedings according to established rules and principles for the protection and enforcement of private rights, including notice and the right to a fair hearing before a tribunal with the power to decide the case.”[46] For the most part, due process is an important tenet of the Constitution and represents an equitable approach to legal proceedings. Similarly, due process falls under two categories: substantive and procedural.

According to Black’s, substantive due process is “the doctrine that the Due Process Clauses of the 5th and 14th Amendments require legislation to be fair and reasonable in content and to further a legitimate governmental objective.”[47] Substantive due process really examines the essence of how the law itself is written, created, and legitimized.[48] Additionally, substantive due process is when we ask ourselves was this law written in a way that is fair and equitable to all who may be charged? An example of a violation of substantive due process would be Congress passing a bill which sets an official religion for the United States of America with the President showing their approval by signing it into law. For more explanation of Substantive Due Process, review Chapter 10 in this textbook.

Conversely, procedural due process is defined as “the minimal requirements of notice and a hearing guaranteed by the Due Process Clauses of the 5th and 14th Amendments, especially if the deprivation of a significant life, liberty, or property interest may occur.[49] Procedural due process notes that if two defendants are charged with the same crime, then they will be afforded the same protections, such as a jury trial, within the criminal justice system regardless of their race, socioeconomic status, gender, religion, ethnicity, and so forth. By way of example, two defendants charged with the same possession of drugs charge with the same evidence and same criminal history should proceed through the criminal justice system in the same way. When anything veers or creates a different result for the same charges, this is an example of a procedural due process violation. Finally, a complete analysis of a procedural due process violation should include a thorough analysis of any exceptions which may apply.

a. Miranda v. Arizona

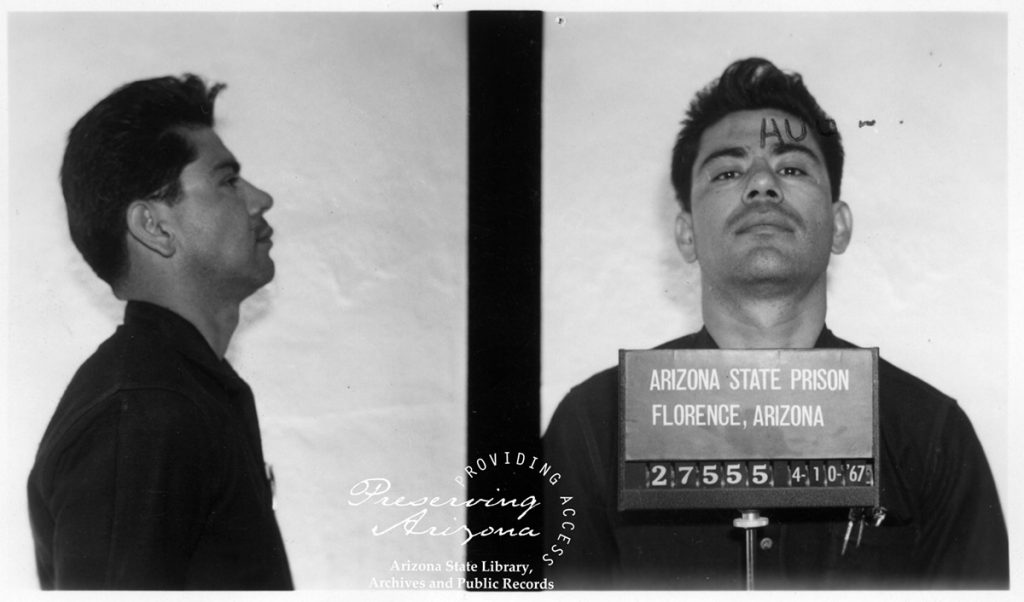

Ernesto Miranda – Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966)[50]

As such, the Due Process in the Fifth Amendment must include a full discussion of Miranda v. Arizona (1966).[51] The landmark case, Miranda v. Arizona (1966), combined four cases with four separate sets of plaintiffs and defendants. In this significant case, the court articulated defendants’ Constitutional rights which law enforcement agents’ must use when a defendant is in custodial interrogation. In Miranda, the suspect was interrogated regarding a kidnapping and rape. During the interrogation, agents secured a verbal confession and written confession admissible at trial. Miranda’s defense attorney objected to both confessions based upon Miranda’s lack of counsel during questioning as well as a failure for Miranda being advised about this privilege against self-incrimination and right to remain silent. Law enforcement agents testified Miranda was aware of legal rights, but was not informed of his right to counsel during interrogation.[52] Ultimately, Miranda was convicted and appealed his case. The Supreme Court would change the protocol for law enforcement agents based upon rights and privileges which suspects possessed, but may not understand or know exist. Cornell Law emphasized the courts’ stance on the flow of interrogation noting, “[w]here the individual answers some questions during in-custody interrogation, he has not waived his privilege, and may invoke his right to remain silent thereafter.”[53]

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

Furthermore, the Miranda warning as identified in Miranda v. Arizona (1966) includes the Fifth Amendment’s self-incrimination right, the Sixth Amendment’s right to counsel as well as the Fourth Amendment’s Constitutional protections. It does not contain specific language and can vary by state. The warning must include some variation of the following elements:

- You have the right to remain silent.

- Anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law.

- You have the right to an attorney.

- If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be appointed for you.[54]

The Miranda warnings are usually followed by a verbal acknowledgment that the suspect has heard and understood the warning. Remember, courts have held that specific words contained in Mirandaare not necessary to comply with the warnings. However, giving the Miranda warnings are just the beginning of the safeguards of a suspect’s Constitutional rights.

After the Miranda warning is given, a person in custody can invoke or waive his or her rights. If the detainee invokes their rights, then they will “put into legal effect or call for the observance of the Constitutional protections” within the Fifth Amendment.[55] The detainee may waive their rights which manifests as “abandon[ing], renounc[ing], or surrender[ing] (a claim, privilege, right, etc.).”[56] One such waiver is the jury waiver which includes “[t]he voluntary relinquishment or abandonment — express or implied — of a legal right or advantage.”[57] It is important to note that most legal authorities require that those who invoke the waiver must do so knowingly, freely and voluntarily. Black’s Law Dictionary emphasizes the standards of a waiver in its definition. “The voluntary relinquishment or abandonment — express or implied — of a legal right or advantage…” The party alleged to have waived a right must have had both knowledge of the existing right and the intention of forgoing it [in order for it to be fully effectuated.][58] At this juncture, all questioning must cease with a call for an attorney. If questioning should restart, then the detainee must agree to proceed without counsel present (agents should memorialize this agreement) as silence can not be construed as a waiver.

Thus, it is imperative that law enforcement agents are clear as to the suspect’s intention when Miranda warnings are necessary. Every situation does not require Miranda warnings. One such incident is when a witness is being questioned about their general impressions of a victim. However, Miranda warnings may be required if the witness becomes a suspect and the questioning becomes custodial interrogation. Therefore, agents should be careful to advise and inform suspects of Miranda warnings soon and often. Consider what occurs if the Miranda warning requirement is violated.

b. Exclusionary Rule

Exclusionary Rule[59]

If the Miranda warning is not given, and a suspect fails to waive their rights, the exclusionary rule may be triggered as discussed in the Fourth Amendment. The exclusionary rule could apply and nullify any statements made causing the evidence to be inadmissible. Thus, this is a case of fruit of the poisonous tree as explained under the Fourth Amendment.

Part V: Right to Just Compensation for Private Property

nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.

The right to just compensation according to this section does not necessarily equal the amount of money a property owner desires or feels is an appropriate value based upon their love and attachment for their property. The just compensation is held as the fair marketable value of the private property which is required from the governmental entity. This process for the government to acquire the land is known as eminent domain. According to Black’s, eminent domain involves “[t]he inherent power of a governmental entity to take privately owned property, especially land, and convert it to public use, subject to reasonable compensation for the taking.”[60] Note a taking is defined as “[t]he government’s actual or effective acquisition of private property either by ousting the owner or by destroying the property or severely impairing its utility. There is a taking of property when government action directly interferes with or substantially disturbs the owner’s use and enjoyment of the property.”[61] These standards must be evaluated before determining a taking has occurred.

a. Eminent Domain

Just Compensation and Eminent Domain relationship[62]

Courts broadly interpret the Fifth Amendment to allow the government to seize property if doing so will increase the general public welfare. Eminent domain refers to the power of the government to take private property and convert it into public use. The Fifth Amendment provides that the government may only exercise this power if they provide just compensation to the property owners. In Kelo v. City of New London (2005), the Supreme Court allowed a taking when the government used eminent domain to seize private property to facilitate a private development.[63] The Court considered the taking to be a public use because the community would enjoy the furthering of economic development. Further, the Kelo court determined that a governmental claim of eminent domain is justified if the seizure is rationally related to a conceivable public purpose.[64]

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

The analysis according to Kelo begins with answering a few questions:

a. Is eminent domain present?

b. if a regulation occurs, then is the regulation a taking?

c. Is just compensation being offered for the taking?

d. Finally, does the taking include meet the public use requirement?

As such, the Kelo decision significantly broadened the government’s takings power. This caused significant controversy and states were quick to act to quell concerns about this expansion of power. In response to Kelo, many states have passed laws which have restricted governments’ takings abilities. One example is – implementing a stricter definition of what constitutes a “public use” which requires a heightened level of scrutiny to justify an action categorized as a taking.[65]

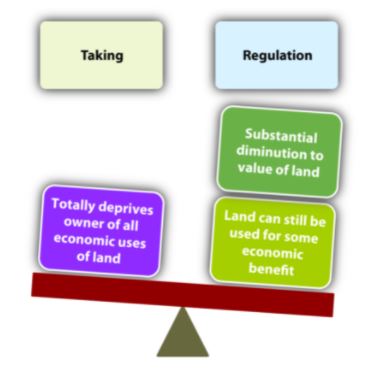

b. When is a Regulation a Taking?

What constitutes a taking?[66]

After determining if eminent domain exists, then one must determine if a regulation is present? If such a regulation exists, then one must determine if the regulation is a legal government taking? How do you determine if a legal taking has occurred? According to Pa Coal Co. v. Mahon (1922), the Supreme Court of the United States held that government regulation will not be deemed a taking unless the regulation severely damages the value of the property.[67] Sometimes, a government regulation infringes upon private property ownership to such an extent that the regulation can be considered a taking, thus requiring just compensation. In United States v. Dickinson (1947), the Supreme Court held that even if the government does not physically seize private property, the action is still a taking “when inroads are made upon an owner’s use of it to an extent that, as between private parties, a servitude has been acquired either by agreement or in course of time.”[68]

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

Additionally, Cornell Law identified a series of Supreme Court cases regulatory takings cases which developed a 4-part test to determine whether a regulation is considered to be a taking.

Is the regulation a taking under Loretto v. Teleprompter Manhattan CATV Corp (1982)?

A government regulation is a taking when the government authorizes a permanent physical occupation of real/personal property

Is the regulation a taking under Lucas v. South Carolina Coastal Council (1992)?

The regulation is a taking when the regulation causes the loss of all economically beneficial/productive uses of the land, unless the regulation is justified by background principles of property law/nuisance law

Is the regulation a taking under Nollan-Dolan v. California Coastal Commission (1987)?

- The regulation is a taking if the government demands an exaction that lacks a nexus with a legitimate state interest or lacks proportionality to project’s impacts

- Exaction – a requirement that the developer provides specified land, improvements, payments, or other benefits to the public to help offset the project’s impacts

Is the regulation a taking under the Penn Central Transportation Co. v. City of New York (1978) balancing test?

Here a court will look at 3 factors:

The character of the governmental action involved in the regulation

A. If the government’s action is a physical action, rather than a “regulatory invasion,” then the action is almost certainly a taking

The extent to which the regulation has interfered with the owner’s reasonable investment-backed expectations for the parcel as a whole

The regulation’s economic impact on the affected prop owner[69]

c. Just Compensation Requirement

After determining that the government taking was valid, then one must determine if the just compensation requirement has been met. In Kohl v. United States (1875), the Supreme Court held that the government may seize property through the use of eminent domain, as long as it appropriates just compensation to the legal owner of the property.[70] How does one identify when just compensation exists? In Loretto v. Teleprompter Manhattan CATV Corp (1982), the Supreme Court clarified that when the government engages in a taking and implements a permanent physical occupation of the property, then the property owner must be given just compensation.[71]

Perhaps, just compensation’s definition sheds some light on the standard as it is “…a payment by the government for property it has taken under eminent domain — [usually] the property’s fair market value, so that the owner is theoretically no worse off after the taking.”[72] The court further defined just compensation based upon the size of the area which the government takes. The court clarified that just compensation must occur regardless if the area is small and the government’s use does not greatly affect the owner’s economic interest. Therefore, the court reiterated any governmental taking warrants just compensation.

d. Public Use Requirement

Not For Public Use[73]

Lastly, if a governmental taking is deemed to have met the just compensation requirement, then the public use requirement must be reviewed. What is public use? According to Black’s, public use is defined as “[a] legitimate public purpose for the condemnation of private property.”[74] Thus, any analysis of public use must include determining “[i]f property is taken for a legitimate public purpose — one that is within the scope of the government’s police power.”[75] If one determines, the government taking was for a legitimate public purpose, then “…the public-use requirement is satisfied, regardless of who physically uses the property once it is taken.”[76] In Kelo, the Supreme Court held that general benefits which a community would enjoy from the furthering of economic development is sufficient to qualify as a “public use.”[77] Therefore, the court’s review for a public use is expansive establishing most government takings as valid.

Critical Reflections:

- Critics assert that grand juries are not their own entity. Instead, critics believe grand juries are an extension of the prosecutor’s office. Read the Trump indictment listed above at Footnote 15. Barring your political affiliations, assess the indictment based upon the language and legal format. Does the indictment meet the legal standards necessary for a “true bill?” Why or why not?

- If due process is a right held by the Fifth Amendment, then why is it implemented differently throughout the criminal justice system?

- Should the government be allowed to use eminent domain? Why or why not?

- United States courts word cloud. (n.d.). United States Courts. Retrieved August 2, 2023, from https://www.uscourts.gov/sites/default/files/fifth_amendment_wordcloud_0.pdf ↵

- Kemp, J. (1958). The background of the fifth amendment in english law: A study of its historical implications. William and Mary Law Review, 1(2), 247–286. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3341&context=wmlr ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Youngson, Nick. Grand jury. CC BY-SA 3.0. Pix4free. ↵

- GRAND JURY, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- INFORMATION, Black’s Law Dictionary (12th ed., 2024). ↵

- PRESENTMENT, Black’s Law Dictionary (12th ed., 2024). ↵

- State v. Baker, 808 S.E.2d 805 (N.C. Ct. App. 2018) ↵

- PRESENTMENT (12th ed., 2024). ↵

- How does a grand jury work? (2020, November 9). Findlaw. https://www.findlaw.com/criminal/criminal-procedure/how-does-a-grand-jury-work.html#:%7E:text=Grand%20juries%20do%20not%20need,(depending%20on%20the%20jurisdiction). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- INDICTMENT, Black’s Law Dictionary (12th ed., 2024). ↵

- NO BILL, Black’s Law Dictionary (12th ed., 2024). ↵

- Hudson, Toby. Brass scales with cupped trays [edited]. CC BY-SA 3.0. Wikimedia Commons. ↵

- Read the indictment. (n.d.). AP News. https://apnews.com/trump-election-2020-indictment. ↵

- CRIMINAL COMPLAINT, Black’s Law Dictionary (12th ed., 2024). ↵

- Wishnia, J. (2021, March 29). How to file a criminal complaint. LegalMatch Law Library. https://www.legalmatch.com/law-library/article/criminal-complaint-lawyers.html ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- U.S. Const. art. I, § 3 ↵

- Youngson, Nick. Double jeopardy. CC BY-SA 3.0. Pix4free. ↵

- Offence vs. Offense—What is the difference? (n.d.). Https://Www.Grammarly.Com/Blog/Offence-Offense/#:~:Text=Offense%20can%20also%20be%20spelled,In%20other%20English%2Dspeaking%20countries%3A&text=The%20adjective%20derived%20from%20offense,American%20and%20British%20English%20alike. Https://Law.Jrank.Org/Pages/1261/Grand-Jury-Screening-Procedures.Html. Retrieved May 17, 2021, from https://www.grammarly.com/blog/offence-offense/#:~:text=Offense%20can%20also%20be%20spelled,in%20other%20English%2Dspeaking%20countries%3A&text=The%20adjective%20derived%20from%20offense,American%20and%20British%20English%20alike.https://law.jrank.org/pages/1261/Grand-Jury-Screening-procedures.html ↵

- Ticak, M. (2023). Offence vs. Offense—What Is the Difference? | Grammarly. Offence Vs. Offense—What Is the Difference? | Grammarly. https://www.grammarly.com/blog/offence-offense/#:~:text=The%20difference%20is%20that%20offense,in%20other%20English%2Dspeaking%20countries. ↵

- OFFENSE, Black’s Law Dictionary (12th ed., 2024). ↵

- JEOPARDY, Black’s Law Dictionary (12th ed., 2024). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Downum v. United States, 372 U.S. 734 (1963); Crist v. Bretz, 437 U.S. 28 (1978). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Martinez v. Illinois, 572 U.S. 833 (2014). ↵

- Martinez v. Illinois, (2014). ↵

- SUBJECT, Black’s Law Dictionary (12th ed., 2024). ↵

- Youngson, Nick. Self-Incrimination. CC BY-SA 3.0. Pix4free. ↵

- PRIVILEGE, Black’s Law Dictionary (12th ed., 2024). ↵

- EVIDENCE, Black’s Law Dictionary (12th ed., 2024). ↵

- Legal Information Institute. (n.d.). Self-incrimination. LII / Legal Information Institute. Retrieved October 2, 2020, from https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/self-incrimination ↵

- SELF INCRIMINATION, Black’s Law Dictionary (12th ed., 2024). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Legal Information Institute, n.d. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Richards, E. (2009, April 19). Privilege against Self-Incrimination. Privilege against Self-Incrimination. https://biotech.law.lsu.edu/map/PrivilegeagainstSelf-Incrimination.html ↵

- Miranda v. Arizona, 384 US 436 (1966). ↵

- Marcus, P. (2006). It’s Not Just About Miranda: Determining the Voluntariness of Confessions in Criminal Prosecutions. Valparaiso University Law Review, 601–644. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1069&context=facpubs ↵

- Marcus, 2006, p. 643. ↵

- You get due process!(n.d.). LinkedIn. Retrieved August 2, 2023, from https://media.licdn.com/dms/image/C5612AQEr8y2y7FYNKg/article-cover_image-shrink_600_2000/0/1567960882457?e=2147483647&v=beta&t=kGCOjb8TDaj1hy5RXyHVhTqQPeOULy7H2orYzx8dJXc ↵

- DUE PROCESS, Black’s Law Dictionary (12th ed., 2024) ↵

- SUBSTANTIVE DUE PROCESS, Black’s Law Dictionary (12th ed., 2024) ↵

- Id. ↵

- PROCEDURAL DUE PROCESS, Black’s Law Dictionary (12th ed., 2024) ↵

- Arizona State Library (n.d.). Ernesto Miranda, 1963. Archives and Public Records, History and Archives Division, Phoenix, Photo #00-0517. Retrieved August 2, 2023 from https://backstoryradio.org/shows/you-have-the-right-to-remain-silent/ ↵

- Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Legal Information Institute, n.d. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- WAIVER, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Youngson, Nick. Exclusionary rule. CC BY-SA 3.0. Pix4free. ↵

- EMINENT DOMAIN, Black’s Law Dictionary (12th ed., 2024) ↵

- TAKING, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024)e. ↵

- The Geyser. (2023, June 13). Is the NSF plan unconstitutional? https://www.the-geyser.com/is-the-nsf-plan-unconstitutional/ ↵

- Kelo v. City of New London, 545 U.S. 469 (2005). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Lesson 6: Constitutional law: Land use, commerce, and federalism. (n.d.). https://water.mecc.edu/courses/Env227/taking.jpg ↵

- Pa Coal v. Mahon, 260 US 393 (1922). ↵

- United States v. Dickinson, 331 U.S. 745 (1947). ↵

- Legal Information Institute, n.d. ↵

- Kohl v. United States, 91 U.S. 367 (1875). ↵

- Loretto v. Teleprompter Manhattan CATV Corp., 458 U.S. 419 (1982). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Levine, Alan. Not Public. CC BY 2.0. Flickr. ↵

- PUBLIC USE, Black’s Law Dictionary (12th ed., 2024) ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Kelo v. City New London (2005). ↵