Chapter 8 – Amendment VIII: Defining Excessive and Cruel & Unusual Punishment

Amendment VIII

Richard J. Forst and Tauya R. Forst

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

8.1 Define the unfamiliar terms of the Eighth Amendment.

8.2 Explain the parts of the Eighth Amendment, including rights and freedoms.

8.3 Determine how reasonable bail helps indigent defendants to avoid appearing guilty.

8.4 Compare the different bail options that may be available to a defendant.

8.5 Describe how the excessive fines clause has been leveraged by government to seize personal property.

8.6 Explain what factors are used to determine if something is cruel and unusual punishment.

8.7 Explain the factors used to determine if a fine is excessive.

KEY TERMS

| Bail | Fine |

| Bail Bond | Imprisonment |

| Cash Bail | Property |

| Cruel and Unusual Punishment | Recognizance |

| Excessive Fine | Writ of certiorari |

Amendment VIII

Passed by Congress September 25, 1789. Ratified December 15, 1791. The first 10 amendments form the Bill of Rights.

Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.

Eighth Amendment: Banning Cruel and Unusual Punishment[1]

INTRODUCTION TO AMENDMENT VIII

As previously discussed, Amendment VIII is part and parcel of the Bill of Rights of the United States Constitution as introduced by James Madison. This amendment, in its uniqueness, is almost an exact duplicate of the English Bill of Rights of 1689 (formerly known as An Act Declaring the Rights and Liberties of the Subject and Settling the Succession of the Crown).[2] The American Bill of Rights, Amendment VIII states “Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted,” while the British Bill of Rights includes this language “That excessive bail ought not to be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.”[3]

Myth: Every defendant is entitled to bail.

Following the English’s example, the American Eighth Amendment has it roots in the Titus Oates case. Oates was tried by the court system for multiple crimes culminating in executions of many people who he wrongfully accused.[4] As you may imagine, Oates’ trial ended without an execution, but included harsh penalties.[5] As a result, there was a need to address how punishments are meted out and when they are appropriate and proportional. In England “cruel and unusual punishment” was outlawed allowing judicial discretion to reasonably adhere to standards against “cruel and unusual” punishment.[6] However, this approach resonated with the United States of America and the Framers began discussions to include the American Bill of Rights (amendments), once the original Constitution was ratified. Thus, the Eighth Amendment boasts of three key portions which underscore how defendants are to be treated within the American criminal justice system.

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT VIII

Three Parts of Amendment VIII

Part I: Right Against Excessive Bail

Excessive bail shall not be required,

Excessive Bail Shall Not Be Required[7]

When reviewing Amendment VIII, one portion leads most discussions. However, bail is a foundational piece of the American criminal justice system and has been broadly and widely debated. Bail allows for great judicial and prosecutorial discretion. In Bell v. Wolfish (1979), the Court introduced a stricter view of the presumption of innocence, indicating it is a doctrine that allocates the burden of proof in criminal trials,

while denying that it appli[es] to a determination of the rights of a pretrial detainee during confinement before his trial has even begun.[8]

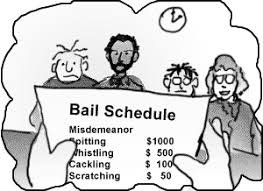

Bail Schedule[9]

Because of this view, judges understand that the right against excessive bail does not support a right to bail for all detainees in all cases. According to Black’s Law Dictionary, bail is defined as “[a] security such as cash, a bond, or property; esp., security required by a court for the release of a criminal defendant who must appear in court at a future time.”[10] There are four common types of bail which exist within the United States bail system:

- release on one’s own recognizance,

- cash bail,

- property bond, and

- cash bond.

Each of these types of bail produces an ability to allow the accused to answer to criminal charges while remaining in the community. If an accused seeks bail, then the best option is receiving bail on one’s own recognizance. Being released on one’s own recognizance or release on recognizance is the least pretrial condition, as it only requires the accused to sign a promise to return to court to answer for pending criminal charges. Black’s defines this concept as “[t]he pretrial release of an arrested person who promises, usu. in writing but without supplying a surety or posting bond, to appear for trial at a later date.”[11] Further, this type of release bears no financial burden for the accused. There are many factors which a judge will consider when determining if a defendant is a good match for release on one’s own recognizance.

The judge considers personal aspects of the accused to determine eligibility such as:

1. criminal history,

2. the seriousness of criminal charges,

3. propensity to flee from the trial as well as

4. the accused’s behavior within the community.

According to Black’s Law Dictionary, recognizance is defined as “[a] bond or obligation, made in court, by which a person promises to perform some act or observe some condition, such as to appear when called, to pay a debt, or to keep the peace; specif., an in-court acknowledgment of an obligation in a penal sum, conditioned on the performance or nonperformance of a particular act.”[12]

Bail should never be used as a punishment.

Remember, bail ensures the accused will appear for trial and all pretrial required hearings. A judge may include additional conditions such as no or limited contact with the alleged victim. After all, the accused is seeking pre-conviction release meaning the accused has not been convicted of a crime; therefore, they should be considered innocent until proven guilty. This presumption of innocence supports the accused in their appearance before the court. When the accused appears without shackles, handcuffs, detention garments, and a disheveled look, the trier of fact (either jurors or judge) may inadvertently attach some level of guilt. However, when the accused is dressed in a suit and tie {suit or dress}, having rested at home the night before the hearing, he {she} may be viewed more favorably.[13]

Another method for obtaining bail is via the option of cash bail. Cash bail is defined as “[a] sum of money (as opposed to a surety bond) posted to secure a criminal defendant’s release from jail.”[14] Research from the Prison Policy Initiative states almost half a million people are detained and awaiting trial in the United States. “Many are jailed pretrial simply because they can’t afford money bail, others because a probation, parole, or ICE office has placed a hold”[15] on their release. The number of people in jail pretrial has nearly quadrupled since the 1980s.”[16]

In February 2021, Governor J.B. Pritzker signed a bill which places Illinois in the forefront of criminal justice as it as been in other areas such as juvenile justice. Governor Pritzker signed “a landmark criminal justice reform package into law…, making the state among the first to eliminate the use of cash bail.”[17]

Bail Bonds.footnote]Schwen, Daniel. Bail Bonds. CC BY-SA. Wikimedia Commons.[/footnote]

Dubbed the Pretrial Fairness Act, the Safety, Accountability, Fairness and Equity-Today (or SAFE-T) Act of 2021 was enacted to make changes to the Illinois’ criminal justice system. Originally, the statute was scheduled to take effect on January 1, 2023. “Nonviolent defendants who cannot pay for release will no longer remain incarcerated before trial, reversing a measure that opponents say criminalizes poverty. Instead, judges must impose the least restrictive conditions necessary to ensure a defendant’s appearance in court.”[18] In reality, the measure was a bipartisan, multiagency attempt to address criminal justice reform in Illinois. Although litigation persisted from across the state, the historical implementation will occur. “The Illinois Supreme Court … upheld the constitutionality of a state law ending cash bail, ordering implementation in mid-September.”[19] The 5-2 ruling creates a path for those charged with minor, nonviolent offenses to be released in a pretrial basis. On the other hand, the ruling is clear to note that those who are at risk for avoiding trial, have violent tendencies, and/or deemed a threat to the public, will remain detained as was the case prior to this act.[20] Both opponents and supporters of this historic approach to cash bail weighed in from the bench. ‘”The Illinois Constitution of 1970 does not mandate that monetary bail is the only means to ensure criminal defendants appear for trials or the only means to protect the public,” Justice Mary Jane Theis wrote in the ruling.”[21] While those who oppose this act spoke from a textualist mode of interpretation, ‘Justices David Overstreet and Lisa Holder White both dissented from the ruling, calling the end to the state’s cash bail a “direct violation of the plain language of our constitution’s bill of rights.'”[22]

A statue outside of the Illinois Supreme Court in Springfield, IL[23]

Yet another option for obtaining bail is the bail bond system. Bail bond is defined as “[a] bond given to a court by a criminal defendant’s surety to guarantee that the defendant will duly appear in court in the future and, if the defendant is jailed, to obtain the defendant’s release from confinement.”[24] This option allows an accused to use a bail bondsperson to make an appropriate payment arrangement if the accused is unable to pay the full bail amount. “In return for the defendant’s putting up a percentage of the total bond, usually 10 percent, the bondsperson will guarantee the remaining amount to the court should the defendant not be present for any court appearance.”[25]

Part II: Right Against Excessive Fines also known as Excessive Fines Clause

nor excessive fines imposed,

Excessive Fines.[26]

When discussing the Eighth Amendment, legal discussions almost automatically go to cruel and unusual punishment. However, the second part of the amendment is almost always ignored. Right against excessive fines imposed within this portion of the amendment points to common aspects of penalty for criminal offenses. Judicial discretion is significant if the fines are not purely proscribed by law. Recall we identified all of the sources of law as described in Chapter 2. As mentioned each level of government – federal, state, and local, refer to the law differently. Codes, statutes, and ordinances, respectfully, lists and provides penalty for criminal matters. According to Fuller, criminal penalties include incarceration (prison), detention (jail), parole, death penalty, probation, fines, or any combination of those punishments.[27]

Criminal fines are included in codes, statutes, and ordinances and may be named solely or in conjunction with other penalties. In general, fines are included in response to less serious offenses, non-violent crimes, which carry pecuniary or theft issues. According to Black’s Law Dictionary, a fine is “[a] pecuniary criminal punishment or civil penalty payable to the public treasury.”[28] Fines are typically seen in the criminal and civil statutes. Fines may arise in a case for various reasons.

Within criminal fines, the U.S. Supreme Court discussed the Excessive Fines Clause in an unanimous and unusual decision. In Timbs v. Indiana (2019), the court explored the central question of whether the Excessive Fines Clause of the Eighth Amendment would apply to the states under the Fourteenth Amendment. The case involved the forfeiture of the accused’s Land Rover, after he was involved in a drug arrest where $1200 fines and costs were at issue. Justice Kagan pointed out in the argument, the issue includes both the incorporation and scope of the Excessive Fines Clause. The Court decided that the Excessive Fines Clause applies to the states, the question is how to determine what the fine should be and when is the fine excessive. The Supreme Court of the United States vacated the Supreme Court of Indiana which allowed the forfeiture of the Land Rover and remanded the case for further proceedings consistent with the Eighth Amendment.

According to Black’s Law Dictionary, an excessive fine is defined as “[a] fine that is unreasonably high and disproportionate to the offense committed.”[29]

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

“The Excessive Fines Clause limits the government’s power to extract payment as punishment for an offense. A fine is excessive when it is grossly disproportionate to the gravity of the offense that it was designed to punish United States v. Bajakajain (1998).[30] Courts must also defer to the legislature regarding the appropriate range of punishment for an offense.”[31] Therefore, judges are required to follow the intent of the law makers when sentencing defendants to fines.

Is the fine excessive?

- Whether the statute was designed to punish the accused;

- The amount of other approved penalties; and

- The harm caused by the accused.[32]

Part III: Right Against Cruel and Unusual Punishments

nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.

Right against cruel and unusual punishment[36]

When discussing the Eighth Amendment, legal discussions reflexively go to cruel and unusual punishment. Even more typical is how such discussions conclude that the Amendment refers only to death eligible cases. According to Black’s Law Dictionary, cruel and unusual punishment is defined as “[p]unishment that is torturous, degrading, inhuman, grossly disproportionate to the crime in question, or otherwise shocking to the moral sense of the community.”[37] The phrase “cruel and unusual” is ambiguous and sometimes convoluted as applied under the Eighth Amendment. This phrase generates much division, dialogue, and disagreement. In fact, most individuals who formulate an opinion on cruel and unusual punishment have not viewed or been closely involved in a case where it is applied to death penalty, capital punishment or death eligible cases. So the question really becomes, does the court view all capital punishment cases as cruel and unusual as noted under the Eighth Amendment?

According to the Congressional Quarterly’s (1979), the court has not deemed the “…death penalty as invariably cruel and unusual.”[38] The court has generally indicated that it would apply the amendment to prohibit punishments it found barbaric or disproportionate to the crime punished.”[39] It is important that we ask the correct question in the death penalty dialogue. According to the Equal Justice Initiative, “The question we need to ask about the death penalty in America is not whether someone deserves to die for a crime. The question is whether we deserve to kill.”[40] The question sparks more discussion than provide answers. The authors of this textbook believe this is appropriate as many legal discussions end in more questions, than answers.

The Supreme Court of the United States noted that the Eighth Amendment’s Right Against “cruel and unusual punishment” applies to many categories of identified prisoner rights. Prisoner rights on this topic, include, but are not limited to the following:

- “The right to humane facilities and conditions

- The right to be free from sexual crimes

- The right to be free from racial segregation

- The right to express condition complaints

- The right to assert their rights under the Americans with Disabilities Act

- The right to medical care and attention as needed

- The right to appropriate mental health care

- The right to a hearing if they are to be moved to a mental health facility.”[41]

These important rights are afforded to incarcerated individuals subject to the United States Constitution and the laws, codes, and acts of the United States of America. These rights are guaranteed regardless of the prisoner’s alleged or confirmed crime, degree of heinousness, and/or the their sentence.[42] Accordingly, this text will delve deeper into four categories associated with the Eighth Amendment’s “cruel and unusual punishment.”

Four Categories applying Cruel and Unusual Punishment

There are four categories to which the Supreme Court of the United States applies the third part of the Eighth Amendment. The phrase “cruel and unusual punishment” as noted above began in a case for harsh and severe prisoner’s sentencing. Therefore, this current application remains in alignment with the Supreme Court in Weems v. United States (1910). The Court would extend this concept to three additional categories.

- Death Penalty

- Imprisonment

- Age, and

- Prisoner’s Rights as evidenced in the sections to follow.

a. Death Penalty

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Supreme Court held in Weems v. United States (1910) that excessive punishments disproportionate to the crime may also be ‘cruel and unusual.’[43] Although the case does not involve the death penalty, the Court identified the perimeters for cruel and unusual punishment.

“… {T}he Court held that punishment is cruel and unusual if it is grossly excessive for the crime. Paul Weems, a government official in the Philippines, was convicted of falsifying pay records. Under a territorial law inherited from the Spanish penal code, Weems was sentenced to cadeña temporal, a punishment involving fifteen years of hard labor in chains, permanent deprivation of political rights, and surveillance by the authorities for life. Since the Philippine Bill of Rights was Congress’s extension to the Philippines of rights guaranteed by the Constitution, the meaning of cruel and unusual punishment was the same in both documents.”[44]

On May 24, 2021, the U.S. Supreme Court denied a writ of certiorari from a Missouri death row inmate, Ernest Johnson.[45] Recall from Chapter 2 how a case proceeds to the Supreme Court of the United States. A writ of certiorari is “[a]n extraordinary writ issued by an appellate court, at its discretion, directing a lower court to deliver the record in the case for review … The U.S. Supreme Court uses certiorari to review most of the cases that it decides to hear.”[46] It is this power which allowed the court to shape its destiny. According to Wright, “[c}ertiorari control over the cases that come before the Court enables the Court to define its own institutional role.”[47]

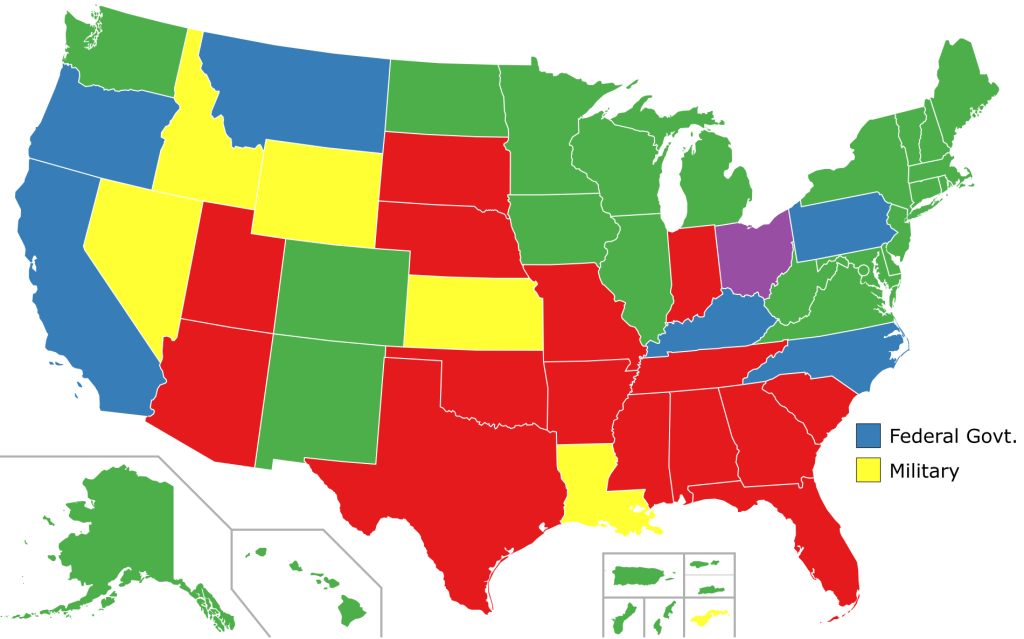

States with the Death Penalty, Death Penalty Bans, and Death Penalty Hiatuses[48]

The application for a writ included Johnson’s request for a firing squad instead of the lethal injection which he believed could lead to an excruciating death.[49] The defendant suffers from epilepsy as a result of a brain tumor as well as damage caused by surgery to remove the tumor. He contends that he will experience excruciating seizures if Missouri executes him by lethal injection of the drug pentobarbital. The court’s requirement for four justices to agree to consider the case (otherwise known as granting the writ of certiorari) was a 6-3 decision, with all of the Republican appointees in the majority and the Democratic appointees in the minority. Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in the dissent, “Missouri is now free to execute [the inmate] in a manner that, at this stage of the litigation, we must assume will be akin to torture given his unique medical condition.”[50]

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

On May 14, 2021, Governor Henry McMaster of South Carolina signed Act 43 that forces South Carolina death row inmates to choose how to die: electric chair or firing squad.[51] The law was passed to expedite executions, which had been halted since 2011 due to a shortage of the drugs needed to execute by lethal injection. South Carolina Supreme Court placed a stay on Richard Moore as he was the first prisoner subject to execution under this law. Subsequently, the choice of execution remains unresolved as the South Carolina Supreme Court heard arguments of constitutionality of this act.

Further complicating this matter is how a death row prisoner may feel when he dies. In June 2022, the Supreme Court of the United States decided a case in which a Georgia death row inmate requested death by firing squad as opposed to the state authorized death by lethal injection due to his “severely compromised” veins.[52] Michael Nance was arrested, convicted, and sentenced to death in 2002 for shooting and killing a bystander after a bank robbery in 1993. Subsequently, Nance has requested habeas review of this sentence. The motion was denied. Later, Nance brought a “suit under §1983 to enjoin Georgia from using lethal injection to carry out his execution. Lethal injection is the only method of execution that Georgia law now authorizes. Nance alleges that applying that method to him would create a substantial risk of severe pain {due to the condition of his collapsed veins.]”[53] This suit was dismissed as untimely, while the 11th Circuit court rejected the suit based upon its categorization as a second and subsequent habeas petition.

Thus, Nance appealed the decision to the Supreme Court of the United States. Writing for the court in a 5-4 decision, Justice Kagan stated “a death row inmate may attempt to show that a State’s planned method of execution, either on its face or as applied to him, violates the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on ‘cruel and unusual’ punishment.” As a result, the Supreme Court granted Nance the ability to pursue his lawsuit against the state of Georgia for death by firing squad.

Do you agree with the court? In your opinion did the court get it right? Why or why not?

b. Imprisonment

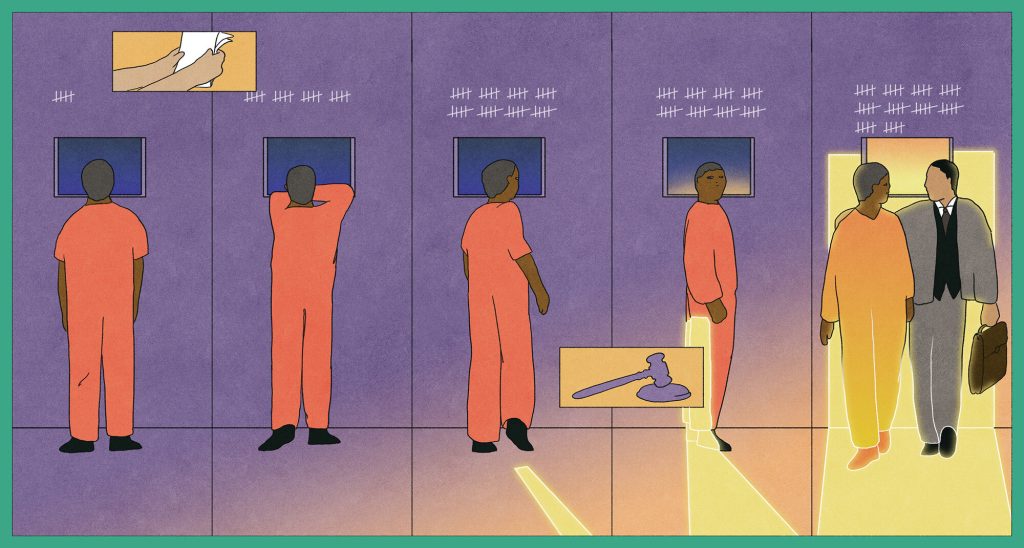

Empowering Prosecutors to Review Older Sentences[54]

The cruel and unusual punishment as penalty suggests evaluation of the Eighth Amendment must include proportionality of the crime as it relates to several key factors. The Supreme Court of the United States emphasized the proportionality of punishment of any crime – felony or misdemeanor, as noted in Solem v. Helm (1983).[55] The Solem factors include

- “the severity of the offense,

- the harshness of the penalty,

- the sentences imposed on others within the same jurisdiction, and

- the sentences imposed on others in different jurisdictions.”[56]

We must remember that the Supreme Court of the United States has the ability to overturn itself as previously stated in Chapter 2. Thus, this case set the application for cruel and unusual punishment while inmates are in confinement or imprisonment. According to Black’s Law Dictionary, imprisonment is defined as “[t]he act of confining a person, [especially] in a prison”[57] or “[a] building or complex where people are kept in long-term confinement as punishment for a crime, or in short-term detention while waiting to go to court as criminal defendants; [specifically}, a state or federal facility of confinement for convicted criminals, [especially] felons.”[58] In Harmelin v. Michigan (1991), the court overturned their prohibition on disproportionality, but noted that the defendant’s life sentence without the possibility of parole is an unconstitutional extreme case which could violate the Eighth Amendment.[59]

According to Cornell Law, a later holding affirmed how the court regards the disproportionality standard affirming in Lockyer v. Andrade (2003), that proportionality is not the norm, but is only available in “exceedingly rare” and “extreme cases.”[60]

Despite the stated desire for proportionality in Solem v. Helm (1983), the reality in today’s America is quite different. Additionally, Alexander in “The New Jim Crow,” reported the overwhelming majority of people swept into the system of mass incarceration are charged with nonviolent crimes and drug offenses. In 2019, data reported by the Vera Institute of Justice revealed that police make more than ten million arrests each year, but only 5% of those arrests are for violent offenses.[61] Drug crimes remain the largest category of arrests. According to the Pew Research Center, eight out of ten people on probation and two-thirds of the people on parole have been convicted of nonviolent crimes.[62] Almost half, 48%, of people in state prisons today have been convicted of nonviolent crimes.[63] The statistic is actually worse than it appears, because those convicted of violent crimes generally serve much longer sentences, skewing their share of the prison population upward. Therefore, while the punishment of non-violent offenders may be considered cruel, it is anything but unusual.[64]

c. Age

14-year-0ld Allen Miller from Miller v. Alabama[65]

In Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption, attorney Bryan Stevenson recounts many first-hand accounts of how human nature engages in cruel and unusual punishment according to his laymen’s definitions as explored in many of his cases.[66] Attorney Stevenson represented clients who alleged age as a mitigating factor for their reduction in sentencing based upon the disproportionality of the crime. Juveniles have many issues and challenges as they “act impulsively, recklessly, and irresponsibly.”[67]

Because of the juveniles’ diminished ability to critically think and behave, Stevenson argued in Graham v. Florida (2011) that “barred life-without-parole sentences for juveniles convicted of nonhomicide offenses” is cruel and unusual punishments.[68]

Attorney Stevenson and the Equal Justice Initiative invited the Supreme Court of the United States to further expand the application of age within the cruel and unusual punishment as it reviewed a combined case in Miller v. Alabama (2012).[69] In Miller, the court held that mandatory life without the possibility of parole is unconstitutional amongst juveniles. Unfortunately, the court did not summarily dismiss all life without the possibility of parole sentences noting that if they are part and parcel of a juveniles’ sentence, then it should occur few and far in between.[70] “The Court did not ban all juvenile life-without-parole sentences, but held that requiring judges to consider ‘children’s diminished culpability, and heightened capacity for change’ should make such sentences “uncommon.”[71] Therefore, it appears the Supreme Court of the United States is set forth the legal standard for determining if defendant’s Eighth Amendment rights amount to cruel and unusual punishment.

Although Miller v. Alabama was a pivotal juvenile decision, approximately one-quarter of states changed their stance on juvenile sentences. These states “applied Miller retroactively to people already serving the banned sentence and granted them new sentencing hearings.”[72] Furthermore, “a handful of states, including Louisiana, refused to [allow a new sentencing hearing].”[73] In Montgomery v. Louisiana (6-3), the United States Supreme Court held Miller v. Alabama barred mandatory life without parole sentences for youth. The Court extended this holding retroactively.”[74]

This landmark decision paved the way for a remarkable occurrence. Mr. Joseph Ligon, 83, the oldest living juvenile lifer was released from prison after 68 years.[75] At that time, Pennsylvania and Louisiana were two states that refused to apply Miller v. Alabama retroactively. Pennsylvania’s refusal created an opportunity for one of the worst miscarriages of juvenile justice by the United States. At 15, Joseph Ligon was convicted of two counts of first-degree murder after a drinking spree with three other youth ended tragically with two people dead. The court sentenced Ligon to life without parole. After Montgomery, the courts reset each of Mr. Ligon’s sentences to thirty-five years. All sentences were to be served concurrently with an opportunity for parole. When offered, Ligon refused parole on several occasions, citing instead that he wanted to leave without governmental conditions. Ligon eventually brought suit which resulted in his release from prison without oversight.[76] However, housing Ligon for almost 7 decades has its costs. “According to an estimate by the Vera Institute of Justice, it cost the state of Pennsylvania nearly three million dollars to incarcerate Ligon for 68 years, and that’s without medical costs.”[77]

Furthermore, a Mississippi petite jury convicted Brett Jones of murdering his grandfather when he was 15 years old. Murder in Mississippi carried a mandatory sentence of life without parole. Jones was sentenced to life without parole. Jones’ conviction pre-dated both Miller v. Alabama (2012) and Montgomery v. Louisiana (2016), but he was granted a resentencing to ensure that the penalty addressed the Miller and Montgomery challenges. Recall Miller held that the Eighth Amendment permits a life-without-parole sentence for a defendant who committed a homicide when he or she was under 18, but only if the sentence is not mandatory and the sentencer therefore has discretion to impose a lesser punishment.”[78] Recall Montgomery provides this standard retroactively. In this case, Jones was resentenced to the same life without parole. Jones requested review of this outcome from the SCOTUS. The court upheld (6-3) the constitutionality of Jones’ life without parole sentence. The court further noted that

“In the case of a defendant who committed homicide when he was under 18, Supreme Court precedent does require the sentencer to make a separate factual finding of permanent incorrigibility before sentencing the defendant to life without parole; a discretionary sentencing system is both constitutionally necessary and constitutionally sufficient.”[79]

This examination reminds the country of the chipping away at the progress made for juvenile offenders who receive a mandatory life without parole sentence under 18 years old. These offenders should be sentenced, but must have a review which includes “a sentencer decid[ing] whether the juvenile offender before it is a child whose crimes reflect transient immaturity or is one of those rare children whose crimes reflect irreparable corruption” as noted in Tatum v. Arizona.[80] In her dissent, Justice Sotomayor joined by Justice Kagan and Justice Breyer, noted Jones was requesting such a determination. Therefore, Justices Kavannaugh, Roberts, Barrett, Gorusch, and Alito joining in the opinion which upheld the life without parole sentence, but claimed to leave Miller and Montgomery undisturbed. The justices attributed their opinions to the state’s sovereign ability to execute justice as they see fit.[81]Thus, the majority shifted federal judicial authority found in Miller and Montgomery back to the states for final determination.

d. Prisoners’ Rights

Deplorable prison conditions[82]

There are many examples where cruel and unusual punishment may apply to prisoners housed in the prisons and jails. These violations of prisoners’ rights include, but are not limited to:

- protection against beatings, Hudson v McMillian (1992) where the Supreme Court held an Eighth Amendment violation occurred when the guards maliciously and sadistically beat Hudson.[83]

- lack of adequate medical care, Estelle v. Gamble (1976) where a prison employees “deliberate indifference” to the “serious medical needs” of prisoners is an Eighth Amendment violation.[84]

- lack of care – resulting from overcrowding, Brown v. Plata (2011) where the Court stated prisoners would suffer and potentially die without food sustenance and proper medical care.[85]

- sexual assault by inmates or guards, Bearchild v. Cobban (2020) where the Court held that “sexual conduct for the staff member’s own sexual gratification, or for the purpose of humiliating, degrading, or demeaning the prisoner” violates a prisoner’s right against cruel and unusual punishment.[86]

- sexual assault by inmates or guards – federal code, Civil Rights Actions – Convicted Person’s Claim of Sexual Assault which lists:

“Under the Eighth Amendment, a convicted prisoner has the right to be free from “cruel and unusual punishments.” To prove the defendant deprived [name of applicable plaintiff] of this Eighth Amendment right, the plaintiff must establish the following elements by a preponderance of the evidence:

-

[Name of applicable defendant] acted under color of law;

-

[Name of applicable defendant] acted without penological justification; and

-

[Name of applicable defendant] [touched the prisoner in a sexual manner] [engaged in sexual conduct for the defendant’s own sexual gratification] [acted for the purpose of humiliating, degrading, or demeaning the prisoner].”[87]

Furthermore, the Eighth Amendment provides protections for the basic human needs of prisoners, as prisoners remain humans even, and especially when, in confinement. In Farmer v. Brennan (1994), prisoners were afforded “humane conditions of confinement,” to “ensure that inmates receive adequate food, clothing, shelter, and medical care.”[88] Still, inmates suffer severe and despicable conditions while confined.

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

In Taylor v. Riojas (2020), the Supreme Court of the United States, in a per curiam opinion, noted that the petitioner could sue under the Eighth Amendment for confining him in two inhumane cells over the course of six days.[89]

Taylor was housed in the first cell which contained human feces everywhere including the floor, ceiling, windows, walls, and faucet creating a fear in Taylor. These uninhabitable conditions affected Taylor’s physical and mental well-being. As Taylor heightened his responses, this treatment only worsened. Taylor was placed naked in a freezing cell with an inoperable drain. Unfortunately, Taylor involuntarily relieved himself and was forced to sleep naked in his and other persons’ bodily waste. The court deemed these conditions appropriate to provide a basis for a lawsuit.[90] Specifically, the court noted that the correctional officers in this situation should have known that the prisoner’s cell conditions amounted to “cruel and unusual” punishment. The court stated that when the officers were “[c]onfronted with the particularly egregious facts of this case, any reasonable officer should have realized that Taylor’s conditions of confinement offended the Constitution.”[91] The court in Taylor set forth the legal standard of a reasonable officer, when evaluating whether an Eighth Amendment violation for prisoner’s right occurs.

Finally, the Supreme Court of the United States applied cruel and unusual punishment to women in confinement during childbirth. Recall, the Eighth Amendment prevents officials in a jail or prison from acting with deliberate indifference to an inmate’s serious medical needs. Obviously, the Court notes childbirth as a serious medical need. Unfortunately, both federal and state violations persist with 173,000 women and girls incarcerated as of March 2023. These women are forced to endure incomprehensible pain and restraint during childbirth. Essentially, these practices continue and impact about 5-10% of restrained women and girls who gave birth in many types of restraints.[92] These restraints include, but are not limited to: “shackles, flex cuffs, soft restraints, hard metal handcuffs, a black box, Chubb cuffs, leg irons, belly chains, a security (tether) chain, or a convex shield.”[93] Because prisoners’ rights are constitutionally protected under the Eighth Amendment cruel and unusual punishment clause, these claims are sometimes heavily litigated.

One such civil case filed in a federal court out in New Jersey addressed this issue for an incarcerated mom. The prisoner was incarcerated on non-violent drug charges, but later died from an unrelated illness. The case continued as the estate wanted the county to make improvements for pregnant prisoners. Her loved ones detailed the deceased, incarcerated mom’s experience when they explained that the Middlesex County Jail officials “routinely shackled her wrists, ankles, and waist during prenatal visits, as she was transported to the hospital and during labor and childbirth.”[94] The deceased inmate’s estate alleged the mental and physical challenges associated with being shackled during her pregnancy and throughout labor and delivery led Middlesex County representative to settle for $750,000.[95]

In most cases, the “cruel and unusual punishment” violations stem from prisoners’ serious medical needs up to and including death. Prisoners, as humans, are entitled to human dignity. What is human dignity? According to Hopwood, “If you translated {human dignity} into policy, it would mean that people in prison would be protected from physical, sexual, and emotional abuse and would be provided with adequate mental health and medical treatment.”[96] The right against cruel and unusual punishment requires legislatures as well as the Supreme Court of the United States to weigh in and trace both the Framers’ intention and the current evolution for a holistic solution to this important legal issue including a protection of physical, sexual, emotional, mental and physical health. Therefore, when thinking of Amendment VIII and its rights, remember to acknowledge all major parts of the amendment as opposed to the most infamous “cruel and unusual punishment” for a complete analysis.

Critical Reflections:

- Review the bail schedule listed in this chapter as well as this ruling issued by the Illinois Supreme Court. What is the reasoning used by the court to support their constitutional finding?

- Do people convicted of nonviolent crimes, such as drug offenses, belong in the same prison population as people convicted of violent crimes? If not, what form of punishment would meet the standards of the Eighth Amendment?

- Review methods of execution here. What are the legal methods of executions used in the United States? Explain how a prisoner is able to challenge the method of their execution. You must state both sides of the argument.

- Review the Marshall Project here. What states have the ability to review old sentences? When should prosecutors use their authority to review old sentences? What factors help prosecutors determine if a sentence is cruel and unusual?

- Define the restraints such as shackles, flex cuffs, soft restraints, hard metal handcuffs, a black box, Chubb cuffs, leg irons, belly chains, a security (tether) chain, and a convex shield. Do you believe these restraints during childbirth violates a mother’s Eighth Amendment right against “cruel and unusual” punishment?

- Case law in recent years such as Taylor v. Riojas (2020) has highlighted inhumane treatment of prisoners. How does that inform how you will perform your career in law enforcement understanding detainees, defendants and even convicts have rights.

- 8th Amendment. CC BY. Image by Epic Top 10 Site. Flickr. ↵

- Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2020, March 19). Bill of Rights. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Bill-of-Rights-British-history ↵

- Levy, M. (2018, July 12). Eighth Amendment. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Eighth-Amendment ↵

- Bessler, J. (2019). A century in the making: The glorious revolution, the american revolution, and the origins of the U.S. Constitution’s eighth amendment. William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal, 27, 989–1077. https://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2086&context=all_fac ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Henry, Matthew. Woman in jail. CC0: Public domain. ↵

- Bell v. Wolfish, 441 U.S. 520, 533 (1979) ↵

- Bail schedule. (n.d.). [Slide show]. NACDL. https://www.nacdl.org/getattachment/76e01bfc-9e62-4838-97cb-4db3f5bb21ee/bail-presentation.pdf ↵

- BAIL, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- RELEASE ON RECOGNIZANCE, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Etemad, N. (2019). To shackle or not to shackle? the effect of shackling on judicial decision-making. Review of Law and Social Justice, 28(2). https://gould.usc.edu/students/journals/rlsj/issues/assets/docs/volume28/Spring2019/2-4-etemad.pdf ↵

- BAIL, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Rabuy, B., & Kopf, D. (2016, May 10). Detaining the poor: How money bail perpetuates an endless cycle of poverty and jail time [Press release]. Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/incomejails.html ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Evans, E., & Oceguera, R. (2021, February 23). Illinois criminal justice reform ends cash bail, changes felony murder rule. Injustice Watch. https://www.injusticewatch.org/news/2021/illinois-criminal-justice-reform-cash-bail-felony-murder/#:%7E:text=Harper)-,Illinois%20Gov.,the%20use%20of%20cash%20bail.&text=%E2%80%9CToday%20is%20a%20historic%20first,%2C%E2%80%9D%20said%20Illinois%20State%20Sen. ↵

- Evans & Oceguera, 2021. ↵

- Franklin, J. (2023, July 18). Illinois Supreme Court rules in favor of ending the state’s cash bail system. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2023/07/18/1188349005/illinois-ends-cash-bail-system-state-supreme-court ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Von Liski, Randy. Justice and Power Sculpture, Illinois Supreme Court Building, Springfield, Illinois. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. Flickr. ↵

- BOND, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- American Bar Association. (2019, September 9). How courts work. https://www.americanbar.org/groups/public_education/resources/law_related_education_network/how_courts_work/bail/ ↵

- Nguyen, Trong Khiem. nộp tiền khắc phục hậu quả ("Pay compensation"). Public domain. Flickr. ↵

- Fuller, J. (2018). Intro to Criminal Justice. Oxford University Press, Oxford (1st Edition). ↵

- FINE, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- United States v. Bajakajain, 524 U.S. 321 (1998) ↵

- Carroll, P. (2020, April 5). Issues of excessive fines coming to a court near you. Trends In State Courts. https://www.ncsc.org/trends/monthly-trends-articles/2019/issues-of-excessive-fines-coming-to-a-court-near-you#:%7E:text=A%20claim%20based%20upon%20the,it%20was%20designed%20to%20punish. ↵

- LII / Legal Information Institute. (n.d.). Excessive fines. Retrieved March 25, 2021, from https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/excessive_fines ↵

- FINE, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- PROPERTY, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Mobilus in Mobili. VIII. CC BY-SA 2.0. Wikimedia Commons. ↵

- CRUEL AND UNUSUAL PUNISHMENT, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Congressional Quarterly's Guide to the U.S. Supreme Court 575 (Elder Witt ed., 1979) ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Children in adult prison. (2021, January 13). Equal Justice Initiative. https://eji.org/issues/children-in-prison/ ↵

- Findlaw.com’s team (Ed.). (2017, July 20). Rights of inmates. Findlaw.com. Retrieved July 17, 2023, from https://www.findlaw.com/civilrights/other-constitutional-rights/rights-of-inmates.html ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. 349 (1910). ↵

- "Weems v. United States 217 U.S. 349 (1910)." Encyclopedia of the American Constitution. . .Retrieved June 30, 2023 from Encyclopedia.com: https://www.encyclopedia.com/politics/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/weems-v-united-states-217-us-349-1910 ↵

- Johnson v. Precythe, 593 U.S. _________ (2021) ↵

- CERTIORARI, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Charles Alan Wright et al., Federal Practice and Procedure §4004, at 22 (2d ed. 1996). ↵

- Atakuzier. Death penalty in the United States with hiatuses [updated 12/27/24]. CC BY-SA 4.0. Wikimedia Commons. ↵

- Johnson v. Precythe, 2021. ↵

- Washington Post, “New law makes inmates choose electric chair or firing squad,” May 17, 2021 ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Nance v. Ward, 597 US _ (2022). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Nadel, M., & Lee, C. (2022b, November 11). Prosecutors in these states can review sentences they deem extreme. few do. The Marshall Project. https://www.themarshallproject.org/2022/11/11/prosecutors-in-these-states-can-review-sentences-they-deem-extreme-few-do-it ↵

- Solem v. Helm, 463 U.S. 277 (1983). ↵

- Id. ↵

- IMPRISONMENT, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- PRISON, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Harmelin v. Michigan, 501 U.S. 957 (1991) ↵

- Lockyer v. Andrade, 538 U.S. 63 (2003) ↵

- Alexander, M. (2020). The new jim crow (mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness - 10th anniversary edition) (1st ed.). NEW PRESS. ↵

- Sawyer, W., & Wagner, P. (2020, March 24). Mass incarceration: The whole pie 2020 [Press release]. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2020.html#slideshows/slideshow1/2 ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Alexander, 2020. ↵

- Totenberg, N. (2012, March 20). Do juvenile killers deserve life behind bars? NPR. https://www.npr.org/2012/03/20/148538071/do-juvenile-killers-deserve-life-behind-bars ↵

- Stevenson, B. (2015). Just mercy: A story of justice and redemption (Reprint ed.) One World. ↵

- Children in adult prison. (2021, January 13). Equal Justice Initiative. https://eji.org/issues/children-in-prison/ ↵

- Stevenson, 2015. ↵

- Miller v. Alabama, 567 US _ (2012). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Children in adult prison. (2021, January 13). Equal Justice Initiative. https://eji.org/issues/children-in-prison/ ↵

- Miller v. Alabama, 2012. ↵

- Children in adult prison. (2021, January 13). Equal Justice Initiative. https://eji.org/issues/children-in-prison/ ↵

- Montgomery v. Louisana, 577 US _ (2016) ↵

- Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.v. Ligon, 1845 EDA 2017 (Pa. Super. Ct. 2019). ↵

- Id. ↵

- CBS News. (2021, March 16). After 68 years in prison, “juvenile lifer” Joe Ligon is free and hopes for a “better future.” CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/joe-ligon-longest-serving-juvenile-lifer/ ↵

- Jones v. Mississippi, 593 U.S. ___ (2021). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Tatum v. Arizona, 580 U. S. ___, ___ (2016) (SOTOMAYOR, J., concurring in decision to grant, vacate, and remand) (slip op., at 3) (internal quotation marks omitted). ↵

- Jones v. Mississippi, 2021. ↵

- How atrocious prisons conditions make us all less safe. (2021, August 23). Brennan Center for Justice. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/analysis-opinion/how-atrocious-prisons-conditions-make-us-all-less-safe ↵

- Hudson v McMillian, 503 U.S. 1 (1992) ↵

- Estelle v. Gamble, 429 U.S. 97 (1976). ↵

- Brown v. Plata, 131 S.Ct. 1910 (2011) ↵

- Bearchild v. Cobban, 947 F.3d 1130, 1144 (9th Cir. 2020) ↵

- 42 U.S.C. Sec. 1983, 9.26 ↵

- Farmer v. Brennan, 511 U.S. 825, 832 (1994). ↵

- Taylor v. Riojas, 592 U.S. _________ (2020). ↵

- American Bar Association. (n.d.). Cruel & unusual punishment - conversation starter. Retrieved October 22, 2020, from https://www.americanbar.org/groups/public_education/programs/constitution_day/conversation-starters/cruel-and-unusual-punishment/ ↵

- Taylor v. Riojas (2020). ↵

- Clarke, J., & Simon, R. (2013). Shackling and Separation: Motherhood in prison. AMA Journal of Ethics, 15(9), 779–785. https://doi.org/10.1001/virtualmentor.2013.15.9.pfor2-1309 ↵

- Does shackling incarcerated women during childbirth violate the Eighth Amendment? (n.d.). https://www.americanbar.org/groups/litigation/committees/civil-rights/articles/2020/does-shackling-incarcerated-women-during-childbirth-violate-the-eighth-amendment/ ↵

- Joe Atmonavage, NJ Advance Media for NJ.com. (2022, September 13). N.J. county settles case for $750K after woman says she was shackled during labor. Nj. https://www.nj.com/news/2022/09/nj-county-settles-case-for-750k-after-woman-says-she-was-shackled-during-labor.html ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Brennan City for Justice, 2021. ↵