Chapter 12 – Amendments III, VII, XI & XVI: Regulating the Government

Amendment III, Amendment VII, Amendment XI, & Amendment XVI

Richard J. Forst and Tauya R. Forst

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

12.1 Identify the unfamiliar terms of the Third Amendment.

12.2 Define quartering, troops, and house according to the Third Amendment.

12.3 Identify the unfamiliar terms of the Seventh Amendment.

12.4 Define value in controversy, suits, and common law according to the Seventh Amendment.

12.5 Identify the unfamiliar terms of the Eleventh Amendment.

12.6 Define judicial power, law or equity, and Foreign state according to the Eleventh Amendment.

12.7 Identify the unfamiliar terms of the Sixteenth Amendment.

12.8 Define lay, collect, and census according to the Sixteenth Amendment.

12.9 Explain the parts of the Sixteenth Amendment.

12.10 Describe governmental and sovereign immunity.

12.11 Summarize the taxing power of the federal government.

12.12 Explain how Congress exerts their power according to the Sixteenth Amendment.

KEY TERMS

| Apportionment | Petit Jury |

| Census | Prescribe |

| Constitutional Prohibition | Prohibition |

| Direct Income Tax | Quartering of Soldiers |

| Governmental Immunity | Sovereign Immunity |

| Income | Taxation Power |

| Judicial Power | Trial |

Amendment III

Passed by Congress September 25, 1789. Ratified December 15, 1791. The first 10 amendments form the Bill of Rights.

No Soldier shall, in time of peace be quartered in any house, without the consent of the Owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.

Amendment III[1]

INTRODUCTION TO AMENDMENT III

Amendment III is the least likely amendment to be referenced in judicial opinions. Not only is it rarely mentioned, but SCOTUS has never relied on its content as a sole basis for a Supreme Court decision. Thus, the question becomes what was the significance of this amendment that it became part and parcel of the Bill of Rights (the first 10 amendments ratified after the original constitution), but is rarely referenced? The question lies in the troubled history and foundation for the Third Amendment. In all actuality, the Third Amendment answered a problem exhibited in English law.

As previously mentioned, most of the constitutional provisions and amendments were centered in English law. English law contained several sources which included common law, legislation, as well as legal standards with their roots in Parliament, the Crown and the courts. These sources were the foundation for almost all of the United States’ laws, particularly in the earlier formation of the country. As a result, these important concepts were included in the Constitution based upon the Quartering Acts of 1765 and 1774 which provided British troops to take cover in colonial homes with the military regulation.[2]

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

This military posture continued as the British troops forced the owners of the private residences to house them during the American Revolution. This forced quartering of soldiers became intolerable and was evidenced in the pushback of the Declaration of Independence, where increased numbers of troops and standing armies were supported without any additional support from legislation.[3]

According to Black’s Law Dictionary, quartering of soldiers is defined as

“[t]he furnishing of shelter or lodging to one or more people, esp. to soldiers. In the United States, a homeowner’s consent is required before soldiers may be quartered in a private home during peacetime. During wartime, soldiers may be quartered in private homes only as prescribed by law. The Third Amendment generally protects U.S. citizens from being forced to use their homes to quarter soldiers.”[4]

Unfortunately, the English perspective did not include an alternative to the private residents quartering soldiers (as defined above). The distrust of quartering soldiers in private homes translated to an alignment against quartering troops in barracks as a standing army as well.[5] This mentality provided the catalyst for colonies to develop and enact similar laws. Delaware, Maryland, Massachusetts and New Hampshire, all held the belief that the quartering of soldiers would become problematic if left unchecked. Thus, they provided a similar version of the Third Amendment within their colonies’ Bill of Rights or Declaration of Rights.[6]

However, the fruition of such fears was never realized and the Third Amendment was rarely invoked by SCOTUS. Oddly, when SCOTUS engaged the Third Amendment it did not include soldiers or quartering at all. Instead SCOTUS has expanded the reach of the Third Amendment with the angle of private citizens having legally defined and protected rights such as the right against quartering troops. Additionally, when certain parties have invoked the Third Amendment in lower federal courts, its usage was flatly rejected as a reliable posture.[7] This rejection did not completely preclude the use of the Third Amendment. SCOTUS noted in Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), a 7-2 decision authored by Justice Douglas, the Court held that there is a constitutional basis to protect the right of marital privacy against state restrictions on contraception. Although this right to privacy was not explicitly stated, the court identified the First, Third, Fourth, and Ninth Amendments as references for constitutional authority. Specifically, the “[t]hird Amendment, in its prohibition against the quartering of soldiers “in any house” in time of peace without the consent of the owner, is another facet of that privacy.”[8] SCOTUS has never decided a case based solely on the Amendment III.

A prohibition and more importantly a constitutional prohibition is defined as “[a] proscription contained in a constitution, esp. one on the making of a particular type of statute (e.g., an ex post facto law) or on the performance of a specified type of act.”[9] Additionally, SCOTUS has never decided a case based solely on the Third Amendment. However, the most notable case in reference to the Third Amendment is Engblom v. Carey (S.D.N.Y. 1983) from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit.[10] This is the closest case which includes a direct reference to quartering soldiers. The question before the court was whether the state violated the Third Amendment when the governor activated the National Guard and quartered them in two correctional officer’s dorm rooms located on the state penitentiary complex. This case is fascinating and held that the renting correctional officers were “owners” of their quarters as well as the National Guard were deemed “soldiers” for the purposes of the Third Amendment.[11] Finally, no additional analysis has occurred since 1983.

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT III

Part 1

No Soldier shall,

in time of peace be quartered in any house,

without the consent of the Owner,

Upon a literal analysis of this verbiage, a soldier would include any persons enlisted in the American military branches – Air Force, Army, Coast Guard, Marine Corps, Navy, and Space Force. However, the court in Engblom v. Carey (S.D.N.Y. 1983) extended this analysis to include the National Guard as well.[12] Further, the amendment explains soldiers may be housed in any [private] quarters. The language precludes quartering soldiers which is defined by Black’s Law Dictionary as “[t]he assigning of military personnel to a place for food and lodging, usu. in a barracks.”[13] This prohibition may not occur in time of peace. This phrase is quite important and appears to refer to times without war and/or rumors of war. Some interpretations lend itself to a period of peace which may occur during a time of war. At any rate, a soldier may not be quartered during a true time of peace or a period of peace without the consent of the owner of the private quarters. This includes rental quarters as evidenced in Engblom v. Carey (S.D.N.Y. 1983).[14]

Part 2

nor in time of war,

but in a manner to be prescribed by law.

The amendment allows homeowners to retain their ownership and autonomy over their property, except when the soldiers’ housing is a military necessity. According to Black’s Law Dictionary, prescribe is defined as “[t]o dictate, ordain, or direct; to establish authoritatively (as a rule or guideline).”[15] Thus, a soldier is not limited to military designated housing during time of war, but it must meet the established authority or legal approval of the law. Further, a soldier is not prohibited from being quartered in a time of war either. This time of war may be armed or unarmed, domestic or foreign, and public or private. The authority for the war power is located in U.S. Const. Art. I, §8, Cl. 11-14 and coincides with the law.

Amendment VII

Passed by Congress September 25, 1789. Ratified December 15, 1791. The first 10 amendments form the Bill of Rights.

In Suits at common law, where the value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial by jury shall be preserved, and no fact tried by a jury, shall be otherwise re-examined in any Court of the United States, than according to the rules of the common law.

Amendment VII[16]

INTRODUCTION TO AMENDMENT VII

As the Bill of Rights was drafted, many of the earlier amendments referred to criminal proceedings. However, the Seventh Amendment refers to civil proceedings as there was no direct amendment which addressed these proceedings prior to this amendment. The federal convention revealed the intention to include such an amendment in the Bill of Rights. “On September 12, 1787, as the Convention was in its final stages, Mr. Williamson of North Carolina ‘observed to the House that no provision was yet made for juries in Civil cases and suggested the necessity of it.'”[17] In fact, the convention entertained a motion to add a clause to Art. III, §2 which would include language regarding federal jury trials. A trial is defined as “[a] formal judicial examination of evidence and determination of legal claims in an adversary proceeding.”[18] This effort failed. Thus, the Seventh Amendment was included as one of the original changes to the original United States Constitution. As a result of its inclusion in the Bill of Rights, the purpose of the Seventh Amendment began to emerge. “The Amendment has, for its primary purpose, the preservation of ‘the common law distinction between the province of the court and that of the jury, whereby, in the absence of express or implied consent to the contrary, issues of law are resolved by the court and issues of fact are to be determined by the jury under appropriate instructions by the court.'”[19]

ANALYSIS Of AMENDMENT VII

In Suits at common law,

where the value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars,

the right of trial by jury shall be preserved,

and no fact tried by a jury,

shall be otherwise re-examined in any Court of the United States,

than according to the rules of the common law.

In the Seventh Amendment, the verbiage of suits refers to lawsuits at common law as described in Chapter 2. The amendment specifically refers to those actions or lawsuits which request more than $20 in damages yielding a right to a jury. A jury is defined as “[a] group of persons selected according to law and given the power to decide questions of fact and return a verdict in the case submitted to them.”[20] This section allows a right of trial by jury to be maintained providing an opportunity for parties to invoke the right when they deem it appropriate. The right of trial by jury is also known as jury trial or petit jury. Petit jury is defined as “[a] jury ([usually] consisting of 6 or 12 persons) summoned and empaneled in the trial of a specific case.”[21] The purpose of the petit jury in a civil, or common law, case is for its members to determine whether the plaintiff proves the elements of the statute with the legal standard of preponderance of the evidence (more than 50%). The elements of the violation are found in the ordinance, statute, or codes depending upon the jurisdiction. After the petit jury deliberates in a civil case, the civil petit jury finds for the plaintiff or the defendant and addresses the amount of damages.

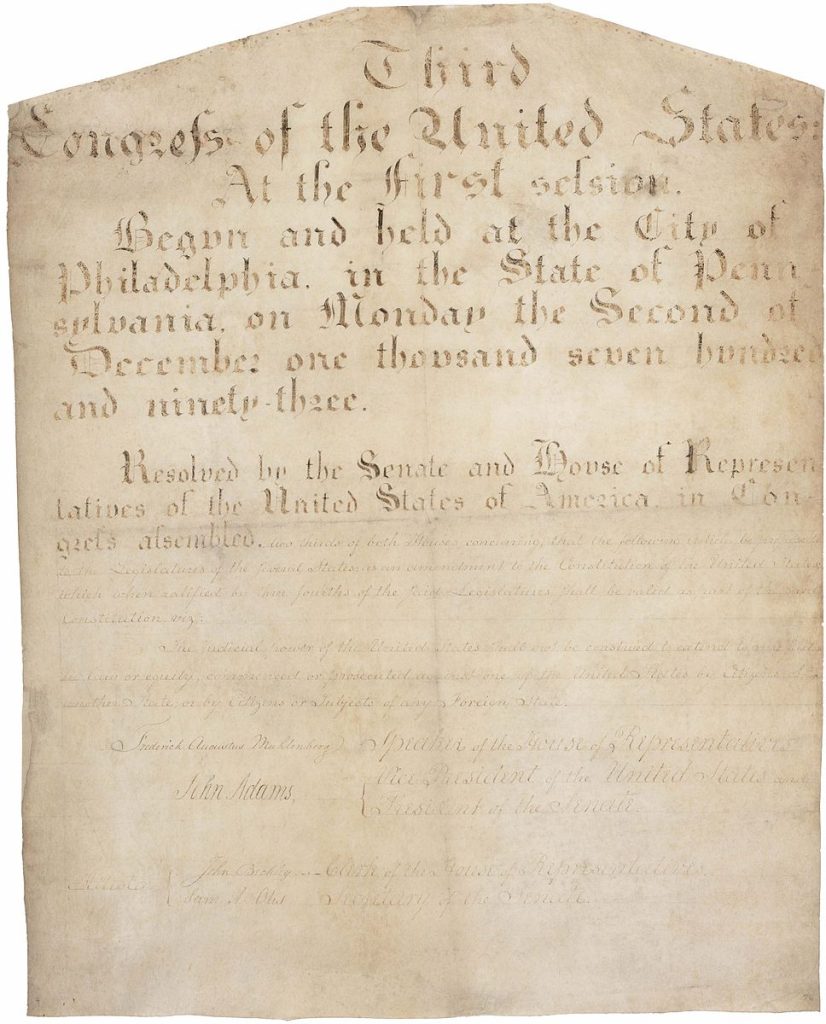

Amendment XI

Passed by Congress March 4, 1794. Ratified February 7, 1795. The 11th Amendment changed a portion of Article III, Section 2.

The Judicial power of the United States shall not be construed to extend to any suit in law or equity, commenced or prosecuted against one of the United States by Citizens of another State, or by Citizens or Subjects of any Foreign State.

Amendment XI[26]

INTRODUCTION TO AMENDMENT XI

The Eleventh Amendment, similar to the other amendments in the Constitution, has its roots in the battle for the American Revolution (also known as the Revolutionary War or the United States War of Independence). During this war, many debts were incurred. As a result, the plaintiff, Chisholm, the executor of the estate of Robert Farquhar, sued the state of Georgia for the debts incurred and the money owed to him for goods Farquhar provided during the Revolutionary War.[27] Georgia never acknowledged the debt and did not defend its claims. Georgia invoked the British concept of sovereign immunity. Sovereign immunity is defined as “[a] government’s immunity from being sued in its own courts without its consent.”[28] Georgia claimed that as a state and a sovereign power, no citizen could sue the state unless Georgia acquiesced to the court’s jurisdiction of the lawsuit. The concept of sovereign immunity was based upon the deference to the crown as the law. Because of the deference to monarchs, this immunity protection has long existed. Thus, Georgia posited that it is immune to citizens’ lawsuits in federal court unless and until Georgia provides consent to the litigation.[29]

The Supreme Court of the United States addressed this concept of sovereign immunity in an attempt to provide clarity for this approach. In Chisholm v. Georgia (1793), SCOTUS rejected the claim of sovereign or state governmental immunity.[30] To the contrary, the court held that Article III, the foundation of the federal courts, precluded state governmental immunity. Therefore, the court in Chisholm explained that its holding was based upon the action of the states’ ratification of the United States Constitution which SCOTUS noted was the states’ action of relinquishing their governmental immunity.[31]

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT XI

The Judicial power of the United States shall not be construed to extend to any suit in law or equity, commenced or prosecuted against one of the United States by Citizens of another State, or by Citizens or Subjects of any Foreign State.

The Eleventh Amendment included the judicial power of the United States contained in Art. III, §2. The judicial power referenced in this amendment is defined as “[t]he authority vested in courts and judges to hear and decide cases and to make binding judgments on them; the power to construe and apply the law when controversies arise over what has been done or not done under it.”[32] According to federal law, the Supreme Court of the United States is vested with judicial power. Whereas, Congress establishes inferior courts under its purview. The Eleventh Amendment protects states within the federal court if the state’s citizens from State A chooses to sue the state’s citizens from State B or another country is known as government immunity, governmental immunity, or sovereign immunity.[33] Governmental immunity is defined as “[a} government’s immunity from being sued in its own courts without its consent. Congress has waived most of the federal government’s sovereign immunity.” Sovereign immunity is a rarity for SCOTUS review. However, this concept was explored in PennEast Pipeline Co. v. New Jersey (2021).[34] Under Art. I, §8 and the interstate commerce clause, Congress passed the Natural Gas Act (NGA) of 1938 to regulate the transportation and sale of natural gas.[35] As much needed background, in order for a company to build an interstate pipeline, a company must secure a Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) certificate reflecting that such construction “is or will be required by the present or future public convenience and necessity” according to 15 U. S. C. §717f(e).[36] As originally enacted, the NGA did not provide a way for certificate holders to secure property rights in New Jersey. Certificate holders were unable to secure property rights to accomplish building pipelines; therefore, FERC granted petitioner PennEast Pipeline Co. a certificate of public convenience.

PennEast filed suit and sought to exercise the federal eminent domain power under §717f(h) to obtain rights-of-way along the pipeline route approved by FERC. PennEast sought to condemn New Jersey or the New Jersey Conservation Foundation asserted property interests. New Jersey moved to dismiss PennEast’s complaints on sovereign immunity grounds. The District Court denied New Jersey’s motion to dismiss PennEast’s complaints on the basis of sovereign immunity grounds. The Third Circuit vacated the District Court’s order insofar as it awarded PennEast relief with respect to New Jersey’s property interests and concluded §717f(h) did not clearly delegate to certificate holders the Federal Government’s ability to sue nonconsenting States such as New Jersey. As a result, the Supreme Court held that §717f(h) authorizes FERC certificate holders to condemn all necessary rights-of-way, whether owned by private parties or States. As a result, the states waived their sovereign immunity as to the federal eminent domain power.[37]

Compare the above holding to the holding in Torres v. Texas Department of Public Safety (2022).[38] According to Art. I, §8, Congress has the authority to raise and support armies. LeRoy Torres enlisted in Army Reserves in 1989 and was called to active duty in Iraq, 2007. While deployed, Torres was exposed to toxic burn pits receiving an honorable discharge due to the diagnosis of constructive bronchitis.[39] Upon his discharge, Torres requested his former employer, Texas Department of Public Safety (“hereinafter Texas”), to accommodate his constructive bronchitis. Texas refused to accommodate Torres’ request. As a result, Torres filed suit under Uniformed Services Employment and Reemployment Rights Act of 1994 (USERRA). This act gives returning servicemembers the right to reclaim their prior jobs with state employers and authorizes suit if those employers refuse to accommodate veterans’ service-related disabilities.[40] Texas filed a motion and raised the defense of sovereign immunity according to the 11th Amendment to get the claim dismissed. The trial court denied this motion and allowed Torres’ suit to proceed. An intermediate appellate court reversed the trial court, reasoning that Congress could not authorize private suits against nonconsenting States (Texas) pursuant to PennEast Pipeline Co. v. New Jersey.[41] Subsequently, SCOTUS granted certiorari to determine whether, in light of that intermediate court’s intervening ruling, USERRA’s damages remedy against state employers is constitutional.[42] Writing for the Court in a 5-4 opinion, Justice Breyer noted “Text, history, and precedent show that the States, in coming together to form a Union, agreed to sacrifice their sovereign immunity for the good of the common defense.”[43] Finally, this holding reversed and remanded the case to the Texas Court of Appeals according to SCOTUS’ opinion.

Amendment XVI

Passed by Congress July 2, 1909. Ratified February 3, 1913. The 16th Amendment changed a portion of Article I, Section 9.

The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever source derived, without apportionment among the several States, and without regard to any census or enumeration.

Amendment XVI[44]

INTRODUCTION TO AMENDMENT XVI

According to the Constitution Annotated, the Sixteenth Amendment was directly related to previous Congressional powers and Supreme Court cases.[45]

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

Specifically, the Sixteenth Amendment’s roots were firmly planted in a case where the definition of income was explained and applied to taxation.

In Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan & Trust Company (1895), the plaintiff sought to preclude the company where he held shares from complying with the intended taxation of his 10 shares.[46] Farmers’ Loan & Trust Company expressed to its shareholders its desire to comply with the provisions in the Wilson-Gorman Tariff Act of 1894 by paying the tax as well as identifying those who were subject to the tax.[47] Ultimately, the lower level courts ruled for the investment company, but the Supreme Court of the United States accepted the case for review.

The question before the court was “whether the income tax now before it does or does not belong to the class of direct taxes.”[48] The court agreed with the plaintiff and held that clauses of the act were void. According to the population and the requirement of apportionment of direct taxes in the states, a direct income tax breached Art. I, §9. Taxes are either direct or indirect. A direct tax is “[a] tax [that] is levied on individuals and organizations and cannot be shifted to another payer. Often with a direct tax, such as the personal income tax, tax rates increase as the taxpayer’s ability to pay increases, resulting in what’s called a progressive tax.”[49] Ultimately, this change affected two sections of Article I.[/footnote]

“By specifically affixing the language, ‘from whatever source derived,’ it removes the ‘direct tax dilemma’ related to Art. I, §8, and authorizes Congress to lay and collect income tax without regard to the rules of Art. I, §9, regarding census and enumeration.”[50]

Unfortunately, Pollock was an unpopular holding. Soon after, the Democrats capitalized on its lack of popularity during the 1896 platform and reminded the voters that the court usurped its authority in Pollock.[51] On the other hand, working class individuals saw this as the wealthy people and corporations avoiding their fair share of taxes. This fight continues today, as President Joe Biden supported a bill introduced in the House which provides an increased share in taxes for the wealthy and corporations.

Therefore, the Sixteenth Amendment did not provide any additional power of taxation, but worked to prohibit Congress’ previous exhaustive and plenary power of income taxation.[52]

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT XVI

The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes on incomes,

from whatever source derived,

without apportionment among the several States,

and without regard to any census or enumeration.

Amendment XVI[53]

Congress first exercised the federal government’s power to tax in 1861, long before ratification of the Sixteenth Amendment, to finance the Civil War.[54] The first Internal Revenue Act taxed imports, provided for a direct land tax, and imposed a tax of 3% on individual incomes over $800.00.[55] The Act was overhauled in new legislation signed by President Lincoln in 1862. This act created the Internal Revenue Service which levied the first progressive income tax and heavily taxed alcohol and tobacco products.

This section identified and outlined how the Framers granted Congress authority to address taxes. The power referred to within this amendment is a taxing or taxation power defined as “[t]he power granted to a governmental body to levy a tax; especially, the congressional power to levy and collect taxes as a means of effectuating Congress’s delegated powers.”[56] Although the phrase originally appeared in Art. I, §8, it did not include the language “on incomes.” Thus, the question becomes what is income? Black’s defines income as “[t]he money or other form of payment that one receives, [usually] periodically, from employment, business, investments, royalties, gifts, and the like.”[57] As stated above, in Pollock and Black’s Law Dictionary, income tax includes the entirety of a person or entity’s net income.

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

The guide for all things federal income tax is governed by the Internal Revenue Code (hereinafter the IRC) which provides the perimeters for collection and appropriation. The IRC “is the domestic portion of federal statutory tax law in the United States, and is under Title 26 of the United States Code (USC). The IRC has 11 subtitles, including income taxes, employment taxes, coal industry health benefits, and group health plan requirements, and group health plan requirements. The implementing agency of IRC is the Internal Revenue Service (IRS).”[58]

Furthermore, this code is located at Title 26 of the United States Code. Finally, the IRC’s power does not require apportionment or “…allocating or attributing moneys…in a given way…” amongst the states, nor does the IRC tax based upon the census or “[a]n official count of people made for the purpose of compiling social and economic data for the political subdivision to which the people belong.”[59]

The Supreme Court of the United States agreed to hear one case which invokes the Sixteenth Amendment. The appearance of the Sixteenth Amendment is a rarity, but takes front stage when SCOTUS granted certiorari to hear whether the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act provision is constitutional which requires “U.S. taxpayers who owned shares in foreign corporations to pay a one-time tax on their share of the corporation’s earnings, even if those earnings were reinvested in the corporation and the taxpayers did not receive them.”[60] Although, Article I of the Constitution requires Congress to apportion any “direct taxes” among the states, the 16th Amendment’s exception allows Congress to tax “incomes, from whatever source derived,” without apportioning that tax among the states.[61] Charles and Kathleen Moore challenged the tax because they reinvested their earnings as opposed to distributing the dividends. SCOTUS granted review of “whether the 16th Amendment authorizes Congress to tax unrealized sums without apportionment among the states?”[62] Finally, this appeal would mean an additional $15,000 in taxes for the Moores if affirmed.[63]

Critical Reflections:

- Does Congress have the power to tax for a purely regulatory, non-revenue generating goal? Could Congress require all prostitutes to register and pay taxes?

- If a foreign country attacks America, can you envision any circumstances in which the armed forces would be able to quarter soldiers in the homes of private citizens?

- Do you agree that the Eleventh Amendment does not allow states to use their state’s immunity to avoid providing compensation and retribution to its citizens? Explain why or why not?

- Image by Epic Top 10 Site. 3rd Amendment. CC BY. Flickr. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- English law, n.d. ↵

- QUARTERING, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024) ↵

- Wood, G. (n.d.). Interpretation: The third amendment | the national constitution center. National Constitution Center. Retrieved February 13, 2021, from https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/interpretation/amendment-iii/interps/123 ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- English law, n.d. ↵

- Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479, 484 (1965). ↵

- PROHIBITION, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Engblom v. Carey, 572 F. Supp. 44 (S.D.N.Y. 1983). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- QUARTERING SOLDIERS, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Id. ↵

- PRESCRIBE, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Image by Epic Top 10 Site. 7th Amendment. CC BY. Flickr. ↵

- GPO. (n.d.). Seventh amendment. Authenticated U.S. Government Information GPO. Retrieved November 10, 2020, from https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CONAN-1992/pdf/GPO-CONAN-1992-10-8.pdf ↵

- TRIAL, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- JURY, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- PETITE JURY, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Dairy Queen v. Wood, 369 U.S. 469 (1962). ↵

- Lytle v. Household Manufacturing, Inc., 494 U.S. 545 (1990). ↵

- 11th Amendment of the United States Constitution. Public domain. Wikimedia Commons. ↵

- Clark, B., & Jackson, V. (n.d.). Interpretation: The eleventh amendment | the national constitution center. The National Constitution Center. Retrieved December 8, 2020, from https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/interpretation/amendment-xi/interps/133 ↵

- IMMUNITY, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Clark & Jackson, n.d. ↵

- Chisholm v. Georgia, 2 U.S. 419 (1793) ↵

- Id. ↵

- JUDICIAL POWER, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- PennEast Pipeline Co. v. New Jersey, 594 US _ (2021). ↵

- PennEast Pipeline Co. v. New Jersey, 2021. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Torres v. Texas Department of Public Safety, 597 U.S. ___ (2022). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. at 16. ↵

- Image by Epic Top 10 Site. 16th Amendment. CC BY. Flickr. ↵

- Sixteenth amendment: Historical background | constitution annotated | Congress.gov | library of congress. (n.d.). Library of Congress. Retrieved May 8, 2021, from https://constitution.congress.gov/browse/essay/amdt16-1/ALDE_00000999/ ↵

- Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Company, 158 U.S. 601 (1895). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. at 602. ↵

- Tax Foundation. (2023, July 26). Direct Tax | Examples of a direct tax | Tax Foundation’s TaxEDU. https://taxfoundation.org/taxedu/glossary/direct-tax/ ↵

- Smentkowski, B. P. (2019, October 14). Sixteenth Amendment. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Sixteenth-Amendment ↵

- Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Company, 1895. ↵

- See Stanton v. Baltic Mining Co., 240 U.S. 103 (1916) for a full explanation. ↵

- DonkeyHotey. US Treasury Checks - 3D Illustration. CC BY 2.0. Flickr. ↵

- Fishkin, J. R., Forbath, W. E., & Jensen, E. (n.d.). Interpretation: The sixteenth amendment | the national constitution center. The National Constitution Center. Retrieved October 23, 2020, from https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/interpretation/amendment-xvi/interps/139 ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- POWER, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- INCOME, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Internal Revenue Code (IRC). (n.d.). LII / Legal Information Institute. https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/internal_revenue_code_(irc)#:~:text=The%20Internal%20Revenue%20Code%20(IRC,and%20group%20health%20plan%20requirements. ↵

- APPORTIONMENT, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024); CENSUS, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Howe, A., & Amy-Howe. (2023). Justices take up cases on veterans’ education benefits and 16th Amendment. SCOTUSblog. https://www.scotusblog.com/2023/06/justices-take-up-cases-on-veterans-education-benefits-and-16th-amendment/ ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵

- Id. ↵