Chapter 13 – Amendments XII, XX, XXII, & XXV: Electoral College, President, & Vice-President

Amendment XII, Amendment XX, Amendment XXII, & Amendment XXV

Richard J. Forst and Tauya R. Forst

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

13.1 Identify the unfamiliar terms of the Twelfth Amendment.

13.2 Describe how the Electoral College and the popular vote affect election of President and Vice-President.

13.3 Identify the unfamiliar terms of the Twentieth Amendment.

13.4 Describe the lame duck session.

13.5 Identify the unfamiliar terms of the Twenty-Second Amendment.

13.6 Describe historical and present-day Presidential term limits.

13.7 Identify the unfamiliar terms of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment.

13.8 Summarize how the Twenty-Fifth Amendment provides for the permanent, complete succession plan of a President in the event of death, removal, resignation, or incapacity.

13.9 Summarize how the Twenty-Fifth Amendment provides for the permanent, complete succession plan of a Vice-President in the event of death, removal, resignation, or incapacity.

KEY TERMS

| Elector | Nominate |

| Electoral College | Presidential Succession Act of 1948 |

| Inoperative | Succession |

| Lame Duck |

“I voted” stickers[1]

Amendment XII

Passed by Congress December 9, 1803. Ratified June 15, 1804. The 12th Amendment changed a portion of Article II, Section 1. A portion of the 12th Amendment was changed by the 20th Amendment, Section 3.

The Electors shall meet in their respective states and vote by ballot for President and Vice-President, one of whom, at least, shall not be an inhabitant of the same state with themselves; they shall name in their ballots the person voted for as President, and in distinct ballots the person voted for as Vice-President, and they shall make distinct lists of all persons voted for as President, and of all persons voted for as Vice-President, and of the number of votes for each, which lists they shall sign and certify, and transmit sealed to the seat of the government of the United States, directed to the President of the Senate;–the President of the Senate shall, in the presence of the Senate and House of Representatives, open all the certificates and the votes shall then be counted;–The person having the greatest number of votes for President, shall be the President, if such number be a majority of the whole number of Electors appointed; and if no person have such majority, then from the persons having the highest numbers not exceeding three on the list of those voted for as President, the House of Representatives shall choose immediately, by ballot, the President. But in choosing the President, the votes shall be taken by states, the representation from each state having one vote; a quorum for this purpose shall consist of a member or members from two-thirds of the states, and a majority of all the states shall be necessary to a choice. And if the House of Representatives shall not choose a President whenever the right of choice shall devolve upon them, before the fourth day of March next following, then the Vice-President shall act as President, as in case of the death or other constitutional disability of the President.–The person having the greatest number of votes as Vice-President, shall be the Vice-President, if such number be a majority of the whole number of Electors appointed, and if no person have a majority, then from the two highest numbers on the list, the Senate shall choose the Vice-President; a quorum for the purpose shall consist of two-thirds of the whole number of Senators, and a majority of the whole number shall be necessary to a choice. But no person constitutionally ineligible to the office of President shall be eligible to that of Vice-President of the United States.

INTRODUCTION TO AMENDMENT XII

Although the term is not mentioned specifically in the amendment, the Twelfth Amendment refers to the Electoral College. Black’s Law Dictionary defines electoral college as “[t]he body of electors chosen from each state to formally elect the U.S. President and Vice President by casting votes based on the popular vote.”[2] This concept appears to be common sense as we observe and understand elections today; however, the electoral process was not always this simple. As previously mentioned, the electoral college was established in Art. II, §1. The verbiage in this article worked well for the United States until the elections of 1796 and 1800.[3] In order for us to understand how the electoral college evolved, we must first understand how it was established in Art. II, §1.

This electoral process consisted of four significant features:

(1) Electors would vote for the two most qualified individuals (one outside of the elector’s home state).

(2) Electors did not determine whether the two individuals would be President or Vice President. The individual who secures the most votes (if a majority) becomes President, with the runner-up becoming Vice President.

(3) The House of Representatives would decide if no majority or a tie occurs from the elections – with the House’s state delegate having one vote.

(4) Finally, the House of Representatives’ determinations would be made by a fair amount of lame ducks – who may have been defeated in the previous election. Therefore, the final decision would not occur with the new representatives as they were not seated until one year later per the Constitution.

This structure supported the notion that the forefathers wanted the most qualified individual as opposed to the concept of the best political party.

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

The Twelfth Amendment is the fastest ratified amendment in the United States Constitution. The amendment was ratified less than 6 months after its proposal.

Any sense that this concept would be defended was dissipated with the election of 1796. The election emerged with the incumbent John Adams, who was Washington’s Vice President for two terms and was then elected President in 1796.[4] At this time, the electors chose Thomas Jefferson as the Vice President. This would prove to be frustrating in 1800 when this process included political party association as well as running mates.[5] As the 1800 election unfolded, President Adams (Charles Cotesworth Pickney) of the Federalist Party and Vice President Jefferson (Aaron Burr) of the Democratic-Republican Party were candidates for the highest office again, only with running mates.[6]

Aaron Burr – Lieutenant Colonel, Attorney General, and Senator[7]

The Federalists began to analyze what would occur if they cast ballots on the most qualified system and determined that they would not provide all of their votes with Adams and Pickney as this would not be a majority. Thus, the Federalists were determined to avoid a tie and a decision from the House of Representatives (keeping the deciding vote within their grasp). On the other hand, the Democratic-Republicans did not consider all possible outcomes and voted for their party running mates. This led to a tie and the House decided between Jefferson and Burr. This tie launched deep rooted issues within the original electoral process which ultimately led directly to the ratification of the Twelfth Amendment. Jefferson was chosen, inaugurated, and the precedent for peaceful transfer of power began – regardless of one’s political affiliation. However, the cracks in the electoral college were exposed as necessary for repair.[8]

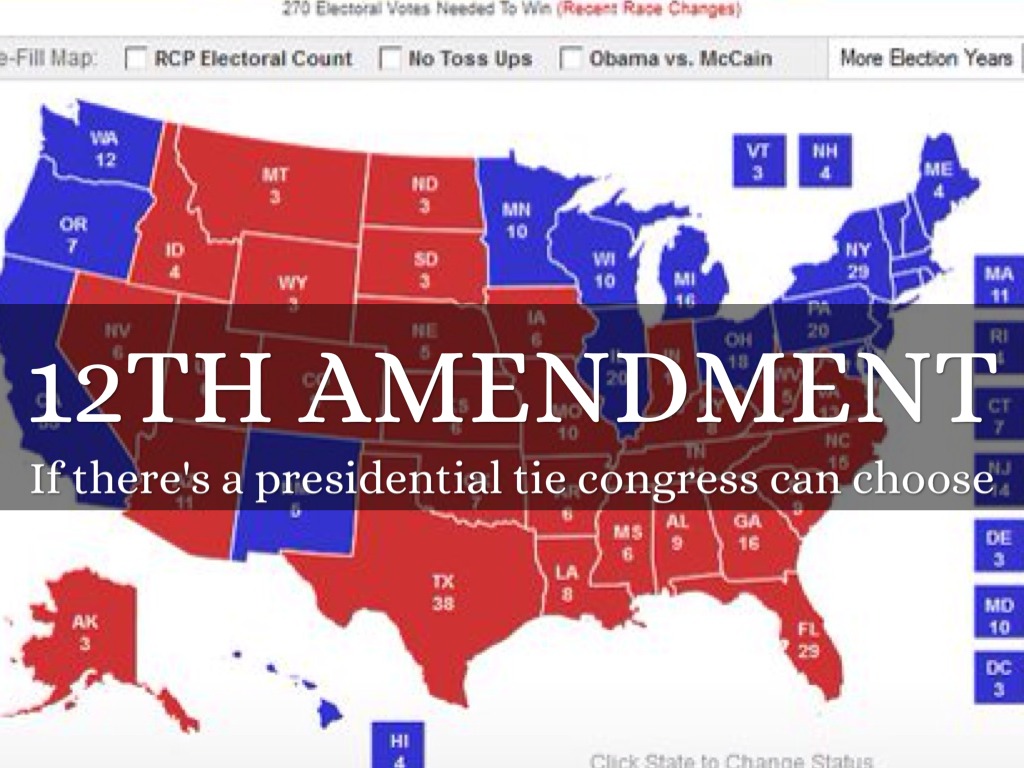

Amendment XII – Resolving Presidential Ties[9]

“While states varied in how they selected presidential electors through the 19th century, electors today are uniformly popularly elected (rather than appointed) and pledged to support a given candidate.”[10] It is worth noting that the Presidential election issue surfaced again in 1824 in the House of Representatives when Andrew Jackson (99) did not win a majority of votes, John Quincy Adams (85), Treasury Secretary William Crawford (41) and Speaker of the House Henry Clay (37), but Jackson had widespread influence in the House and was expected to leverage it to win the election.[11] Now ratified, the Twelfth Amendment required the House of Representatives to only consider those with the top votes; instead, the House chose Adams over Jackson. Not surprisingly, Adams chose Clay as his Secretary of State, due to Clay’s agreement with Adams on the key issues. Jackson was devastated and publicly identified what he believed to be corruption. Jackson stated in response to the 1825 election, “[T]he Judas of the West has closed the contract and will receive the thirty pieces of silver . . . Was there ever witnessed such a bare faced corruption in any country before?”[12]

In recent years, this amendment has proven to be quite important. After acknowledging an inconclusive electoral college result, John Quincy Adams became the only President to be elected by the House of Representatives in 1824. It should be noted that several portions of the Constitution were changed as a result of the Twelfth Amendment. Art. II, §1 changed the dates of the Congressional sessions and when Presidential sessions began. It is noteworthy that this section clearly established the need for a single individual to be the President. The process was safeguarded through the agency of the electoral college. Each elector votes using an instrument in paper or electronic form to name the chief of state, as well as a different ballot if the chief dies and/or resigns (otherwise unable to complete the duties of President). This process seeks to impart transparency as it limits one’s votes to those who reside outside of the same state as the elector. Furthermore, these electors will create running lists for both President and Vice-President. The lists will be forwarded to the Federal capital where the President of the Senate (that is, the Vice-President of the United States) will count all votes in front of the Senate and the House of Representatives. There are two ways that the candidate is chosen. If a majority vote occurs, then the candidate with the majority vote becomes President and Vice-President, respectively. If there is no majority, then the candidate who held the majority of at least three other candidates will be determined by ballot by the House of Representatives. This smaller voting process will require a majority of the House’s members to be present (at least two-thirds) and will decide the President/Vice-President with the majority vote of the House’s members.

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT XII

Part 1 – Electoral College

a. The Electors shall meet in their respective states and vote by ballot for President and Vice-President, one of whom, at least, shall not be an inhabitant of the same state with themselves; they shall name in their ballots the person voted for as President, and in distinct ballots the person voted for as Vice-President, and they shall make distinct lists of all persons voted for as President, and of all persons voted for as Vice-President, and of the number of votes for each, which lists they shall sign and certify, and transmit sealed to the seat of the government of the United States, directed to the President of the Senate; —

b. The President of the Senate shall, in the presence of the Senate and House of Representatives, open all the certificates and the votes shall then be counted;

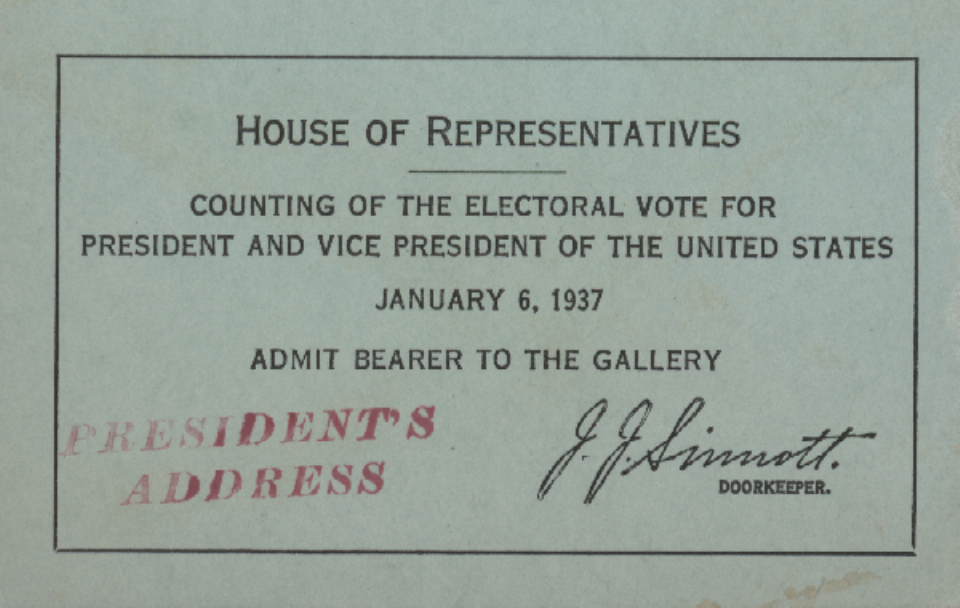

This pass for the Electoral College’s 1937 vote count was used again the same day for the President’s annual message.[13]

This section of the Twelfth Amendment heavily examines electors and how they function in the President and Vice-Presidential election. However, the verbiage itself doesn’t provide context for one of the most important terms in the amendment – electors. What is an elector? According to Black’s Law Dictionary, an elector is “[a] member of the electoral college chosen to elect the U.S. President and Vice President.[14] An elector has a specific method for choosing both the United States President and Vice-President. The electors are required to gather in their states and cast two votes, but one vote must be for a non-native inhabitant of the state.

The difference between Art. II, §1 and the Twelfth Amendment is that the elector must identify the name for President and a separate name for Vice-President.

Electors will maintain a list of all Presidential votes as well as all Vice-Presidential votes keeping a tally of the votes for each candidate with certification and seal to the Vice-President who is the President of the Senate. In Chiafalo v. Washington (2020), in a 9-0 decision, Justice Kagan wrote an opinion for the majority based upon the Twelfth Amendment, while Justice Thomas wrote a concurring opinion based upon the Tenth Amendment.[15] In Chiafalo, a few “faithless” electors sought to change the outcome of the 2016 presidential election by voting for their parties’ choice as opposed to the candidate who carried the popular vote in their state.[16] The court introduced an additional mode of Constitutional interpretation called Constitutional liquidation to reach its reasoning. Justice Kagan reminded the parties that James Madison “wrote that the Constitution’s meaning could be ‘liquidated’ and settled by practice. But the term ‘liquidation’ is not widely known, and its precise meaning is not understood.”[17] Justice Kagan invoked the concept of constitutional liquidation, which relies upon three key elements:

- textual indeterminancy,

- course of deliberate practice, and

- the course of practice had to result in a constitutional settlement.[18]

Further, she relied upon constitutional liquidation to express the court’s opinion which ultimately combined “[t]he Constitution’s text and the Nation’s history [to] both support allowing a State to enforce an elector’s pledge to support his party’s nominee — and the state voters’ choice — for President.”[19] Finally to complete the electoral college process, the Vice-President must open all of the sealed certifications to be counted. Following Chiafalo, the Supreme Court of the United States addressed Colorado Department of State v. Baca (2020). Baca cast a vote for John Kasich as opposed to the person who won the popular vote, Hillary Clinton. After becoming a “faithless elector,” Baca was removed from his office as an elector.

“Electors pledge to vote for the candidate from their party if that candidate wins the most votes in the state (or district in the case of Maine and Nebraska). ‘Faithless electors’ are electors who ultimately vote for someone other than for whom they pledged.”[20]

Faithless Electors

Subsequently Baca sued. The court reversed the decision in Colorado Department of State v. Baca in a per curiam decision upon the reasoning in Chiafalo.

Now that we understand what electors should do, it is important to provide additional information to delve into the particulars as we rarely discuss electors, but they are quite powerful. What are the qualifications for an elector; when are electors chosen; and why do we need to vote if we have electors to vote for President and Vice-President?[21]

a. What are the Qualifications for an Elector?

As previously stated, the U.S. Constitution contains very little information regarding the qualifications of an elector. Art. II, §1, Cl. 2 states “…no Senator or Representative, or Person holding an Office of Trust or Profit under the United States, shall be appointed an elector.” This information along with the language of the Fourteenth Amendment, §3 indicates some terms for disqualification of an elector where it states

“No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any state, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any state legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any state, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof.”

Finally, the certification presented by the appointed electors, “Each State’s Certificates of Ascertainment,” confirms the names of its appointed electors. A State’s certification of its electors is generally sufficient to establish the qualifications of electors.

b. When are Electors Chosen?

Although state law on elector appointments vary, most States follow this procedure on Election Day. The state political parties nominate slates of electors at their State conventions or other meetings. Finally, the citizens vote on the appointment of the electors in the state’s general election.

c. Where do the Electors Meet?

Electors are required to meet in December on the first Monday after the second Wednesday in their own states. The State legislature will determine where in the state, said meetings will occur. At this meeting, the electors cast their votes for President and Vice President.[22]

d. Why Do We Need to Vote if We Have Electors to Vote for President?

The general election identifies for the State’s electors for whom they should cast their ballot for President and Vice-President. When those who vote (popular vote) for a Presidential candidate, you are indicating to the electors which candidate you want your State to vote for at the meeting of electors. The winning Presidential candidate’s state political party selects the electors.

Part 2 – House of Representatives

a. The person having the greatest number of votes for President, shall be the President, if such number be a majority of the whole number of Electors appointed; and if no person have such majority, then from the persons having the highest numbers not exceeding three on the list of those voted for as President, the House of Representatives shall choose immediately, by ballot, the President. But in choosing the President, the votes shall be taken by states, the representation from each state having one vote; a quorum for this purpose shall consist of a member or members from two-thirds of the states, and a majority of all the states shall be necessary to a choice. And if the House of Representatives shall not choose a President whenever the right of choice shall devolve upon them, before the fourth day of March next following, then the Vice-President shall act as President, as in case of the death or other constitutional disability of the President.–

The Electoral College is effective as long as the individual with the greatest votes for President has a majority of the electoral votes, but the process becomes more involved if this is not the case. Just as explained previously in Art. II, § I, the top three vote getters must be chosen from this list by the House of Representatives. The vote will be held by the states, wherein each state = one vote. The choice must be made prior to March 4 of the next year or the Vice-President must act as interim President.

b. The person having the greatest number of votes as Vice-President, shall be the Vice-President, if such number be a majority of the whole number of Electors appointed, and if no person have a majority, then from the two highest numbers on the list, the Senate shall choose the Vice-President; a quorum for the purpose shall consist of two-thirds of the whole number of Senators, and a majority of the whole number shall be necessary to a choice. But no person constitutionally ineligible to the office of President shall be eligible to that of Vice-President of the United States.

As to the Vice-President, the Electoral College is effective as long as the individual with the greatest votes for Vice-President has a majority of the electoral votes. The process becomes more involved if this is not the case. In this case, the top two vote getters must be chosen from this list by the Senate. However, individuals chosen for Vice-President must be eligible for President as well, lest he or she encounters circumstances which requires them to become President.

Amendment XX

Passed by Congress March 2, 1932. Ratified January 23, 1933. The 20th Amendment changed a portion of Article I, Section 4, and a portion of the 12th Amendment (changed the dates of the Congressional sessions and Presidential sessions began).

Section 1

The terms of the President and the Vice President shall end at noon on the 20th day of January, and the terms of Senators and Representatives at noon on the 3d day of January, of the years in which such terms would have ended if this article had not been ratified; and the terms of their successors shall then begin.

Section 2

The Congress shall assemble at least once in every year, and such meeting shall begin at noon on the 3d day of January, unless they shall by law appoint a different day.

Section 3

If, at the time fixed for the beginning of the term of the President, the President elect shall have died, the Vice President elect shall become President. If a President shall not have been chosen before the time fixed for the beginning of his term, or if the President elect shall have failed to qualify, then the Vice President elect shall act as President until a President shall have qualified; and the Congress may by law provide for the case wherein neither a President elect nor a Vice President shall have qualified, declaring who shall then act as President, or the manner in which one who is to act shall be selected, and such person shall act accordingly until a President or Vice President shall have qualified.

Section 4

The Congress may by law provide for the case of the death of any of the persons from whom the House of Representatives may choose a President whenever the right of choice shall have devolved upon them, and for the case of the death of any of the persons from whom the Senate may choose a Vice President whenever the right of choice shall have devolved upon them.

Section 5

Sections 1 and 2 shall take effect on the 15th day of October following the ratification of this article.

Section 6

This article shall be inoperative unless it shall have been ratified as an amendment to the Constitution by the legislatures of three-fourths of the several States within seven years from the date of its submission.

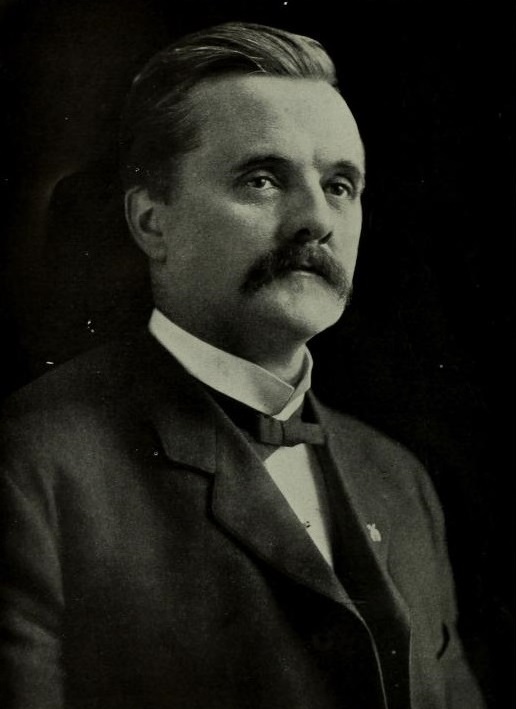

Portrait of Senator George Norris, the author of the first resolution that ultimately created the Twentieth Amendment, c. 1910. (Public Domain)[23]

INTRODUCTION TO AMENDMENT XX

According to History, Arts, and Archives, the 74th Congress (1935-1937) of the United States of America represented the first Congress to adhere to the Twentieth Amendment where “…an old Congress dies and a new one is born on the 3d day of January.”[24] The new method of representation as transportation improved and those who were considered lame ducks could be removed before they could cause an unbalanced or unchecked change on the government. A lame duck is defined as “[a]n official, esp. an elected one, whose term of office will soon end and who therefore has limited power or influence; esp., an elected official serving out a term after a successor has been elected.”[25] Thus, the lame duck elected official is simply sitting in the place of the newly elected “during which a number of members sat who had not been reelected to office.”[26] Similarly, the time which elapsed between the election of the new Congress and the President and Vice-President’s inaugural ceremony is greatly abridged to accommodate these individuals who were not reelected. Therefore, this “…post-election legislative session in which some of the participants are voting during their last days as elected officials” may prove to be quite destructive to a party’s new legislative and new presidential agenda.[27]

Nebraska Senator George Norris understood this uncomfortable political position and worked diligently to pass an answer to this dilemma. Senator Norris was unrelenting in his efforts proposing the Twentieth Amendment to five successive Congressional – with a ratified version in 1923. This remarkable effort spanned the course of almost ten years before Congress finally and quickly ratified it. Although this amendment’s rise to ratification was not without incident, it became a well-received and ratified amendment. After reviewing the process for ratification, we note that most amendments only receive three-fourths support from the states.

This unanimous support of an amendment is unique, but also it was the most expediently ratified amendment as well.In this case, by the end of the state legislative sessions, all states showed support for this change by ratifying the Twentieth Amendment.

Additionally, the Twentieth Amendment has never been the sole subject of a Supreme Court case. In fact, lower courts rarely identify or rely on the amendment in their analysis; however, it is an amendment which functions without incident. Thus, it is important to fully examine the language in the amendment for comprehension. Therefore, this snippet from the Constitution Annotated provides a picture of why the Senate Committee on the Judiciary wanted these changes made as it relates to the lame duck session:

“If it should happen that in the general election in November in presidential years no candidate for President had received a majority of all the electoral votes, the election of a President would then be thrown into the House of Representatives and the membership of the House of Representatives called upon to elect a President would be the old Congress and not the new one just elected by the people. It might easily happen that the Members of the House of Representatives, upon whom devolved the solemn duty of electing a Chief Magistrate for 4 years, had themselves been repudiated at the election that had just occurred, and the country would be confronted with the fact that a repudiated House, defeated by the people themselves at the general election, would still have the power to elect a President who would be in control of the country for the next 4 years. It is quite apparent that such a power ought not to exist, and that the people having expressed themselves at the ballot box should through the Representatives then selected, be able to select the President for the ensuing term. . . .”[28]

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT XX

Section 1

The terms of the President and the Vice President shall end at noon on the 20th day of January, and the terms of Senators and Representatives at noon on the 3d day of January, of the years in which such terms would have ended if this article had not been ratified; and the terms of their successors shall then begin.

Originally, Art. II, § 1, Cl. 1 set the four-year term for the President and Vice President. Section 1 reduced the timeframe from March 4th – January 20th beginning with the election of 1932. In the same way, Congress reduced the timeframe from March 4th – January 3rd which affected the newly ratified Seventeenth Amendment’s six-year senator term. Ironically, this verbiage shortened Representatives’ terms in the Seventy-third Congress to two years while reducing their time to sit from March 4, 1935 – January 3, 1937.

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

If January 3rd occurs on a Sunday, then a different day is chosen for commencing the Senate term.

The section is clear to remind the readers that ratification must occur for the changes to apply. Once ratification occurs then the successors’ terms must begin at the indicated dates to remain compliant with the United States Constitution.

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT XX

Section 2

The Congress shall assemble at least once in every year, and such meeting shall begin at noon on the 3d day of January, unless they shall by law appoint a different day.

This section answers the question of timing for the first mandatory session of Congress.[29] This section replaces Art. I, § 4, Cl. 2. The need for a specific meeting time was enacted in 1867, while it was repealed in 1871. This difference continued to support the thought that Congress needed additional support.[30]

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT XX

Section 3

If, at the time fixed for the beginning of the term of the President, the President elect shall have died, the Vice President elect shall become President. If a President shall not have been chosen before the time fixed for the beginning of his term, or if the President elect shall have failed to qualify, then the Vice President elect shall act as President until a President shall have qualified; and the Congress may by law provide for the case wherein neither a President elect nor a Vice President shall have qualified, declaring who shall then act as President, or the manner in which one who is to act shall be selected, and such person shall act accordingly until a President or Vice President shall have qualified.

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT XX

Section 4

The Congress may by law provide for the case of the death of any of the persons from whom the House of Representatives may choose a President whenever the right of choice shall have devolved upon them, and for the case of the death of any of the persons from whom the Senate may choose a Vice President whenever the right of choice shall have devolved upon them.

This section speaks to the succession of the Presidency. If the President-elect dies after the November election but prior to the January 20th inauguration, the Vice President-elect must become President. Further this section identifies an interim issue of choosing the President or failing to meet the qualifications of President prior to January 20, then the Vice President must temporarily act as President until a President shows appropriate qualifications. It is of note that the issue of qualification may arise from death, disability, succession or other disqualifying factors. Finally, this section authorizes Congress to enact a law which addresses a situation where neither a President nor Vice President-elect qualifies as President. In response to this unprecedented event, Congress enacted the Presidential Succession Act of 1948, but was amended and codified as 3 U.S.C, §19 where Congress is given authority to choose the President if the Electoral College fails to do so. Please note this discussion of Presidential succession continues under the Twenty-fifth Amendment later in this chapter.[31]

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT XX

Section 5

Sections 1 and 2 shall take effect on the 15th day of October following the ratification of this article.

This section is self-explanatory but sets a specific date and time to allow for additional compliance by the government.

ANALYSIS of Amendment XX

Section 6

This article shall be inoperative unless it shall have been ratified as an amendment to the Constitution by the legislatures of three-fourths of the several States within seven years from the date of its submission.

This section provides an alternate end to the amendment if ratification does not occur.

Amendment XXII

Passed by Congress March 21, 1947. Ratified February 27, 1951.

Section 1

No person shall be elected to the office of the President more than twice, and no person who has held the office of President, or acted as President, for more than two years of a term to which some other person was elected President shall be elected to the office of President more than once. But this Article shall not apply to any person holding the office of President when this Article was proposed by Congress, and shall not prevent any person who may be holding the office of President, or acting as President, during the term within which this Article becomes operative from holding the office of President or acting as President during the remainder of such term.

Amendment XXII – Word Cloud[32]

Section 2

This article shall be inoperative unless it shall have been ratified as an amendment to the Constitution by the legislatures of three-fourths of the several States within seven years from the date of its submission to the States by the Congress.

INTRODUCTION TO AMENDMENT XXII

If you are not familiar with Amendment XXII, then you might miss it. It is a quiet amendment, considering its colorful history. Amendment XXII continues to deliver its purpose which is to create a term limit for President. It is of important note that the balance of power among the federal, state, and individual rights always informed the Constitution and its formation. Consider the no-term limit for a Senator; while accepting the term limit for a President. Perhaps this single fact continued to drive the debate surrounding the Twenty-second amendment. Specifically, the amendment was never identified in a Supreme Court case. Although this topic was thoroughly debated by the delegates in the 1787 Constitutional Convention, their thoughts seemed to be geared toward one term varying from three to seven years.[33] Additionally, some delegates floated the idea of a life-time presidency and this perspective received much support; however, both George Washington and Thomas Jefferson declined a third term of Presidency.[34]

According to the National Constitution Center,

“These doubts about unlimited presidential terms of office did not fade away after President Washington set the unofficial two-term precedent in 1796. Scholar Stephen W. Stathis [explained] that Congress considered early versions of presidential term limit amendments in 1803 and 1808, and the Senate approved term-limit resolutions in 1824 and 1826, only to be rejected by the House.”[35]

The process of balancing federal, state and individual power was emphasized in congressional activity. Taken together, the Congressional debate over the presidential terms amounted to almost 150 years and 125 iterations of the presidential term limit amendments.[36] Finally, the National Archive explored this contention when Ulysses S. Grant was elected to two terms in 1876 and 1880. At the end of his second term, he tried to obtain his party’s nomination for a third term. Unfortunately, the party did not obtain the nomination for a third term. In 1876, the National Constitution Center reported that a resolution was submitted indicating “the precedent established by Washington and other Presidents of the United States, in retiring from the Presidential office after their second term, has become by universal concurrence a part of our republican system of government.”[37] This resolution did not comfort those who believed the presidential term must be addressed in a more formal manner. Therefore, the passage of the Twenty-second amendment would prove to be a must.

The President was not always limited to two terms. George Washington, the first President of the United States of America created a precedent of two terms. Ironically, national and global concerns led the 32nd President Franklin D. Roosevelt to secure four terms (the Elections of 1932, 1936, 1940, and 1944). Unfortunately, his fourth term would terminate with his death in 1945.[38]

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT XXII

Section 1

No person shall be elected to the office of the President more than twice, and no person who has held the office of President, or acted as President, for more than two years of a term to which some other person was elected President shall be elected to the office of President more than once. But this Article shall not apply to any person holding the office of President when this Article was proposed by Congress, and shall not prevent any person who may be holding the office of President, or acting as President, during the term within which this Article becomes operative from holding the office of President or acting as President during the remainder of such term.

This section limits the terms of the President. The verbiage indicates three possibilities. First, the President may be elected to up to two four- year terms, if he or she has not been previously elected. Next, a person who has acted as the President temporarily, for less than two years, may be elected to up to two four-year terms. Finally, a person who has acted as the President temporarily, for more than two years, may only be elected to one additional four-year term.

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT XXII

Section 2

This article shall be inoperative unless it shall have been ratified as an amendment to the Constitution by the legislatures of three-fourths of the several States within seven years from the date of its submission to the States by the Congress.

Black’s Law Dictionary defines inoperative as “[h]aving no force or effect; not operative.”[39] This section outlines the terms for ratification of the Twenty-second amendment to become effective within a specified timeframe. In this instance, the amendment was to be ratified by three-fourths of the States but it must be completed within seven years from the original date of submission unlike other amendments without this limitation.

Amendment XXV

Passed by Congress July 6, 1965. Ratified February 10, 1967. The 25th Amendment changed a portion of Article II, Section 1.

Section 1

In case of the removal of the President from office or of his death or resignation, the Vice President shall become President.

Section 2

Whenever there is a vacancy in the office of the Vice President, the President shall nominate a Vice President who shall take office upon confirmation by a majority vote of both Houses of Congress.

Section 3

Whenever the President transmits to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives his written declaration that he is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office, and until he transmits to them a written declaration to the contrary, such powers and duties shall be discharged by the Vice President as Acting President.

Section 4

Whenever the Vice President and a majority of either the principal officers of the executive departments or of such other body as Congress may by law provide, transmit to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives their written declaration that the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office, the Vice President shall immediately assume the powers and duties of the office as Acting President.

Thereafter, when the President transmits to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives his written declaration that no inability exists, he shall resume the powers and duties of his office unless the Vice President and a majority of either the principal officers of the executive department or of such other body as Congress may by law provide, transmit within four days to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives their written declaration that the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office. Thereupon Congress shall decide the issue, assembling within forty-eight hours for that purpose if not in session. If the Congress, within twenty-one days after receipt of the latter written declaration, or, if Congress is not in session, within twenty-one days after Congress is required to assemble, determines by two-thirds vote of both Houses that the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office, the Vice President shall continue to discharge the same as Acting President; otherwise, the President shall resume the powers and duties of his office.

| 1. Vice President | 10. Secretary of Commerce |

| 2. Speaker of the House | 11. Secretary of Labor |

| 3. Senate President Pro Tempore | 12. Secretary of Health and Human Services |

| 4. Secretary of State | 13. Secretary of Housing and Urban Development |

| 5. Secretary of the Treasury | 14. Secretary of Transportation |

| 6. Secretary of Defense | 15. Secretary of Energy |

| 7. Attorney General | 16. Secretary of Education |

| 8. Secretary of the Interior | 17. Secretary of Veterans Affairs |

| 9. Secretary of Agriculture | 18. Secretary of Homeland Security |

Presidential Line of Succession

INTRODUCTION of AMENDMENT XXV

As we examine Amendment XXV, we must begin with some contextual facts which informed Congressional responses as evidenced by Britannica.

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

Prior to the passage [of Amendment XXV], nine presidents – William Henry Harrison, Zachary Taylor, Abraham Lincoln, James Garfield, William McKinley, Woodrow Wilson, Warren G. Harding, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Dwight D. Eisenhower – all experienced health crises that left them temporarily incapacitated. According to the Bill of Rights Institute, death resulted in six of the cases – Harrison, Taylor, Lincoln, Garfield, McKinley, and Harding.[40]

As Congress and the states acted to close the loop for succession in cases of disability, Dr. Felix Yerace of the Bill of Rights Institute, sought to show how President Lyndon Baines Johnson viewed this monumental action.[41] President Johnson explained that Amendment XXV provided a long-awaited response to concerns most Americans held for almost two centuries. The Presidential disability conversation is a continuous debate which began with the constitutional convention and the founding fathers. John Dickinson of Delaware asked this question: “What is the extent of the term ‘disability’ and who is to be the judge of it?” No one replied.”[42] Thus, Amendment XXV was born out of pure necessity. Since the beginning of the country, Congressional leaders grappled with how the country would function if its Commander-In-Chief died or was otherwise unavailable due to a variety of circumstances.

Accordingly, Dr. Yerace identified three concerns which supported the ratification of Amendment XXV.[43] First, the President maintained escalating authority and duties after the ratification of the original constitution. Second, presidential duties in national security and execution at any moment; and finally, the realization that Presidents become injured or ill, but too disabled to continue their responsibilities as President. As a result, there is a vagueness in the language of the constitution as to succession which may end in debilitating illness or injury for a President, but without the end of death.

Remember, the Art. II, § 1, Cl. 6, the predecessor to Amendment XXV states

“In Case of the Removal of the President from Office, or of his Death, Resignation, or Inability to discharge the Powers and Duties of the said Office, the Same shall devolve on the Vice President, and the Congress may by Law provide for the Case of Removal, Death, Resignation or Inability, both of the President and Vice President, declaring what Officer shall then act as President, and such Officer shall act accordingly, until the Disability be removed, or a President shall be elected.”

Congressional pressure to address all three concerns met with some rejection, but eventually the third concern and another presidential assassination of President John F. Kennedy led to real change. The National Constitution Center distinguished the temporary, piecemeal presidential succession plans in Art. II, §1, Cl. 6, the 1947 Presidential Succession Act, and finally President Dwight Eisenhower’s promise to the country and Vice President Nixon to serve as Acting President in the event of his inability due to illness.[44]As a result, Black’s Law Dictionary acknowledges how the passage of Amendment XXV sets forth the permanent, complete succession plan for “…presidency and vice presidency in the event of death, resignation, or incapacity.”[45]

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT XXV

Section 1

In case of the removal of the President from office or of his death or resignation, the Vice President shall become President.

This section addresses the protocol for the voluntary or involuntary removal of a President. Moreover, this section addresses the protocol upon a Presidential resignation being offered. In both instances, the Vice President becomes the Interim or Acting President upon either event occurring. This protocol is known as the presidential succession plan. Black’s Law dictionary defines succession as “[t]he act or right of legally or officially taking over a predecessor’s office, rank, or duties.”[46] In essence this section addresses all ambiguities which previously existed if the President were incapacitated, but still retained the title of President. This provides continuity in leadership for the United States of America in case any unknown presidential disability occurs.

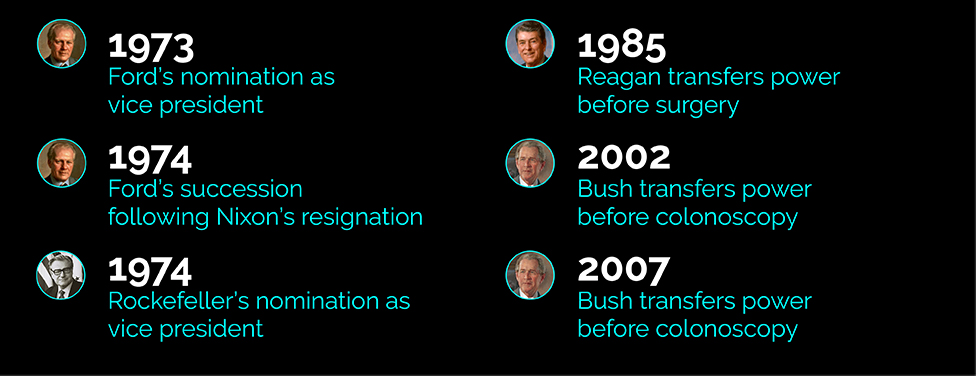

The “acting President” provision of the Twenty-fifth Amendment was first invoked on July 13, 1985, when President Ronald Reagan underwent cancer surgery.[47] He signed a letter transferring power to Vice President George H.W. Bush and sent another letter to the Speaker of the House and president pro tempore of the Senate, as the amendment required. Following his surgery, Reagan notified both that he was fit to resume his Presidential duties. In 2002, President George W. Bush signed similar letters to transfer power temporarily to Vice President Dick Cheney, while Bush was sedated briefly during a colonoscopy medical procedure.[48]

ANALYSIS ROF AMENDMENT XXV

Section 2

Whenever there is a vacancy in the office of the Vice President, the President shall nominate a Vice President who shall take office upon confirmation by a majority vote of both Houses of Congress.

| Vice Presidents who died in office | Vice Presidents who resigned |

| George Madison (1805-1812) | John C. Calhoun (1825-1832) |

| Elbridge Gerry (1813-1814) | Spiro T. Agnew (1969-1973) |

| William Rufus DeVane King (1853) | |

| Henry Wilson (1873-1875) | |

| Thomas A. Hendricks (1885) | |

| Garret A. Hobart (1897-1899) | |

| James S. Sherman (1909-1912) |

Vice Presidential Vacancies

Further, this section addresses gaps in succession for the vice presidency. If a Vice Presidential vacancy occurs, then this section empowers the President to fill the vacancy of the Vice President. Recall the vacancy discussion which occurred earlier in this chapter. Note the vacancy remains under the jurisdiction of the president without Congressional involvement, popular vote, or even the electoral college. This section balances this great increase in power by checks and balances with Congress. The President must nominate or “…propose (a person) for election or appointment” according to Black’s Law Dictionary.[49] A valid nomination must be confirmed by a majority vote of the House of Representatives and the Senate. Thus, this protocol seemed to address the increased concerns over presidential authority.

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

According to Constitution Annotated, the Amendment XXV “…resulted for the first time in our history in the accession to the Presidency and Vice-Presidency of two men who had not faced the voters in a national election.”[50]

To date, this section of the Amendment XXV has been invoked twice. In 1973, President Richard Nixon nominated then Congressman Gerald Ford for Vice-President after Spiro Agnew’s untimely resignation.[51] In 1974, the unlikely use of Amendment XXV would occur again, when then President Nixon resigned and Vice President Ford matriculated to the office and became President Ford.[52] These movements created a vacancy and President Ford nominated Nelson Rockefeller, who was confirmed. According to the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library and Museum, this unique set of circumstances highlighted a new issue regarding succession where voters were not contemplated in choosing President and Vice-President. Therefore, Amendment XXV would not address every issue surrounding presidential disability and vice presidential vacancy, but it did provide answers using such concepts as separation of powers and checks and balances to settle questions which perplexed the framers. Feerick outlined this remarkable feat and identified how it was accomplished, while providing continuity and security to future successions.[53]

Gerald R. Ford, 38th President of the United States (1974-1977), appearing at the House Judiciary Subcommittee hearing on pardoning former President Richard Nixon, Washington, D.C., October 17, 1974.[54]

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT XXV

Section 3

Whenever the President transmits to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives his written declaration that he is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office, and until he transmits to them a written declaration to the contrary, such powers and duties shall be discharged by the Vice President as Acting President.

Presidential Succession and Transfer of Power[55]

Interestingly this section allows the President to voluntarily and temporarily discharge the powers and duties of his or her office. Scholars agree that this notice assumes that if § 3 is not invoked by the President, then he or she is able to discharge their powers and duties for their office. However, when this section is invoked the President must be of sound mind to do so (which removes incapacitation of thought and/or activity of limbs). Also, this section allows for the President to provide notice when he or she believes they are able to resume powers and duties. According to the Congressional Research Service, this ability includes anticipated and unanticipated disabilities for our President. In fact, this clause has been activated twice, but with two different Presidents.

Amendment XXV, §3 was activated under President Ronald Reagan when he “…underwent general anesthesia for medical treatment. It was informally implemented by President Ronald Reagan in 1985 and was formally implemented twice by President George W. Bush [for colonoscopies], in 2002 and 2007, under similar circumstances.”[56]

According to Annenberg Classroom (providing constitutional history), President Ronald Reagan invoked § 3 on July 13, 1985 prior to cancer treatment.[57] He memorialized his intention to temporarily stop his duties and powers by granting Vice President George H.W. Bush the power.[58] Additionally, he sent his written intention to the Speaker of the House and president pro tempore of the Senate anticipating the requirement of §3. Furthermore, President Reagan informed all of his intention to return to his Presidential duties after the treatment. Similarly, Vice-President Kamala Harris became the first woman to possess presidential power. In November 2021, President Joe Biden underwent his first annual physical since becoming president.[59] To accomplish the goal of transferring power under Amendment XXV, §3, “Biden sent a letter to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Democratic Sen. Patrick Leahy of Vermont, the president pro tempore of the Senate, at 10:10 a.m. ET before going under anesthesia.”[60] After the procedure, President Biden transferred the power back by sending a letter evidencing this intention.[61] Thus, when used appropriately by our Commander-in-Chief, §3 supports a smooth transfer of power between the President and Vice-President.

ANALYSIS OF AMENDMENT XXV

Section 4

Whenever the Vice President and a majority of either the principal officers of the executive departments or of such other body as Congress may by law provide, transmit to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives their written declaration that the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office, the Vice President shall immediately assume the powers and duties of the office as Acting President.

Thereafter, when the President transmits to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives his written declaration that no inability exists, he shall resume the powers and duties of his office unless the Vice President and a majority of either the principal officers of the executive department or of such other body as Congress may by law provide, transmit within four days to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives their written declaration that the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office. Thereupon Congress shall decide the issue, assembling within forty-eight hours for that purpose if not in session. If the Congress, within twenty-one days after receipt of the latter written declaration, or, if Congress is not in session, within twenty-one days after Congress is required to assemble, determines by two-thirds vote of both Houses that the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office, the Vice President shall continue to discharge the same as Acting President; otherwise, the President shall resume the powers and duties of his office.

Sections 3 and 4 address different aspects of how the President is regarded when determining succession and disability. The first clause of § 4 points to the specific time when the Vice-President should engage in temporary representation or as Acting President. Specifically, the Congressional Research Service outlines the options as it relates to this shift in power. Firstly, “§4 can be implemented only by the Vice President and either (1) a majority of the Cabinet, or (2) a majority of “such other body as Congress may by law provide.”[62] Secondly, §4 supposes that the President may be of the mindset that he or she is either unfit or reluctant to state the apparent issue of disability. Additionally, the President will not or cannot submit to temporarily removing themselves while this disability exists. Furthermore, this section categorically sets forth four distinct approaches to the presidential disability based upon the Congressional Research Service.

Finally, § 4 was most recently discussed, reviewed and otherwise anticipated after a domestic terrorist attack by individuals who sought to interrupt democracy as well as bring harm to members of our government on January 6, 2021 at the Capitol (the seat of the government) of the United States of America. In response, political leaders, commentators and civilians engaged in a renewed conversation of Amendment XXV. In response, National Public Radio announced the House of Representatives symbolic response to a day of terror which left many capitol police injured and two capital police dead.[63] The House approved a resolution which symbolized their stance of support for those directly and indirectly impacted by the January 6, 2021 insurrection. The resolution strongly suggested that Vice President Mike Pence invoke Amendment XXV without the agreement of President Donald Trump.[64]Occurring within one week after the insurrection, this resolution was the House of Representatives’ push for action as America increased security at the capitol and neared the inauguration of the next president, then President-elect Joseph R. Biden. Therefore, the history of Amendment XXV exposes unresolved issues, while addressing the smooth transfer of power and duties for voluntary or involuntary presidential disability.

CONSTITUTIONAL CLIP

According to the Congressional Research Service, §4 authorizes four potential procedures:

(1) a joint declaration of presidential disability by the Vice President and a majority of the Cabinet or such other body (i.e., DRB) as Congress has established by law. When they transmit a written message to this effect to the President pro tempore and the Speaker, the Vice President immediately assumes the powers and duties of the office as Acting President;

(2) a declaration by the President that the disability invoked under the provisions set out above no longer exists. If the President’s declaration is not contested by the Vice President and the Cabinet or DRB within four days, then the President resumes the powers and duties of the office;

(3) the Vice President and a majority of the Cabinet or DRB, acting jointly, may, however, contest this finding by a written declaration to the contrary to the aforementioned officers. As noted previously, this declaration must be issued within four days of the President’s declaration; otherwise, the President resumes the powers and duties of the office;

(4) if this declaration is transmitted within four days, then Congress decides the issue.

If Congress is in session it has 21 days to consider the question. If a two thirds vote of Members present and voting in both chambers taken within this period disputes the President, the Vice President continues as Acting President. If less than two-thirds of Members in both houses vote to confirm the President’s disability, the President resumes the powers and duties of the office. Alternative actions—a decision by Congress not to vote on the question, a decision to vote to sustain the President’s declaration, or passage of the 21-day deadline without a congressional vote—would also result in the President’s resumption of the office’s powers and duties.”[65]

Finally, some critics believe Amendment XXV doesn’t go far enough. Specifically, for our country to run seamlessly, we must address two concerns with presidents and vice-presidents. In fact, Fordham Law noted some important aspects of Amendment XXV as their graduate, John D. Feerick helped draft the amendment.[66] In fact, they note that there is a possibility of a “dual inability” where both president and vice president may be unavailable. This may lead to a lack of coverage in the presidential succession. Specifically, “Without an able vice president, the 25th Amendment cannot be invoked to declare the president unable. In a dual inability scenario, there is no formal way to initiate succession to the next person in the line of succession.” Therefore, there appears to be gaps in the line of succession which may require additional amendments or congressional acts to secure the federal executive governments.

Critical Reflections:

- The Twelfth Amendment has the potential to provide major answers if our country becomes a multi-political party system as it was in 1948, 1968 and possibly in 2024. What would occur if we had a multi-political system? How will the electoral college function? Is this problematic for other branches within our country?

- Should Presidential terms be limited? Why or why not?

- Is the Electoral College a fair way to elect a President? If yes, why and how would you change the way we elect a President?

- GPA Photo Archive. "I voted" stickers. CC BY-SA 2.0. ↵

- ELECTORAL COLLEGE, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Levinson, S. (n.d.). Interpretation: The twelfth amendment | the national constitution center. The National Constitution Center. Retrieved April 13, 2021, from https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/interpretation/amendment-xii/interps/171 ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Vanderlyn, J. (1802). Portrait of Aaron Burr. Wikimedia Commons. Public domain. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- 12th amendment. (n.d.). Clip Art. https://clipart-library.com/clipart/1722845.htm ↵

- Electoral college & indecisive elections | US house of representatives: History, art & archives. (n.d.). US House of Representatives: History, Art, & Archives. Retrieved October 18, 2020, from https://history.house.gov/Institution/Origins-Development/Electoral-College/#:%7E:text=After%20the%20experiences%20of%20the,the%20other%20for%20Vice%20President.&text=After%20the%20experiences%20of%20the,the%20other%20for%20Vice%20President. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Electoral College Fast Facts | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives. (n.d.). https://history.house.gov/Institution/Electoral-College/Electoral-College/. Public domain. ↵

- ELECTOR, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Chiafalo v. Washington, 140 S.Ct. 2316 (2020). ↵

- Id. ↵

- Baude, W., & Review, S. L. (2019). Constitutional liquidation. Stanford Law Review. https://www.stanfordlawreview.org/print/article/constitutional-liquidation/ ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Chiafalo, 2020. ↵

- What is the law on faithless electors? - Ask a Librarian. (n.d.). https://ask.loc.gov/law/faq/331082#:~:text=Electors%20pledge%20to%20vote%20for,than%20for%20whom%20they%20pledged. ↵

- About the electors. (2021, May 11). National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/electoral-college/electors#:%7E:text=What%20are%20the%20qualifications%20to,shall%20be%20appointed%20an%20elector. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- US National Archives. (2022, October 3). “Constitutional Amendments” Series – Amendment XX – “Date Changes for Presidency, Congress, and Succession.” The Reagan Library Education Blog. Public domain. ↵

- The 20th amendment | US house of representatives: History, art & archives. (n.d.). US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives. Retrieved March 23, 2021, from https://history.house.gov/Historical-Highlights/1901-1950/The-20th-Amendment/. ↵

- LAME DUCK, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Twentieth amendment: Doctrine and practice | constitution annotated | Congress.gov | library of congress. (n.d.). Library of Congress. Retrieved January 28, 2021, from https://constitution.congress.gov/browse/essay/amdt20-2/ALDE_00001006/5/13./ ↵

- Twentieth amendment: Doctrine and practice | constitution annotated | Congress.gov | library of congress. (n.d.-b). Library of Congress. Retrieved November 30, 2020, from https://constitution.congress.gov/browse/essay/amdt20-2/ALDE_00001006/ ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Image by Top 10 website. "A word cloud featuring 22nd Amendment." Flickr. CC BY. ↵

- Interpretation: Twenty-Second amendment | the national constitution center. (n.d.). The National Constitution Center. Retrieved March 17, 2021, from https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/interpretation/amendment-xxii/interps/149 ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Interpretation: Twenty-Second amendment | the national constitution center. (n.d.). The National Constitution Center. Retrieved March 17, 2021, from https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/interpretation/amendment-xxii/interps/149 ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- INOPERATIVE, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024) ↵

- Smentkowski, B. (n.d.). Britannica. Twenty-Fifth Amendment. Retrieved September 20, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Twenty-fifth-Amendment ↵

- The Twenty-Fifth amendment. (2018). Bill of Rights Institute. https://billofrightsinstitute.org/e-lessons/the-twenty-fifth-amendment ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Cait, C., & Pozen, D. (n.d.). Interpretation: The Twenty-Fifth amendment | the national constitution center. The National Constitution Center. Retrieved November 18, 2020, from https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/interpretation/amendment-xxv/interps/159 ↵

- TWENTY-FIFTH AMENDMENT, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- SUCCESSION, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- NOMINATE, Black's Law Dictionary (12th ed. 2024). ↵

- Twenty-Fifth amendment: Doctrine and practice | constitution annotated | Congress.gov | library of congress. (n.d.). Library of Congress. Retrieved January 13, 2021, from https://constitution.congress.gov/browse/essay/amdt25-2/ALDE_00001014/ ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Feerick, J. (1995). The Twenty-Fifth amendment: An explanation and defense. Wake Forest Law Review, 30, 481–503. https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1382&context=faculty_scholarship ↵

- U.S. News and World Report. Gerald Ford hearing. Wikimedia Commons. Public domain. ↵

- Presidential Succession Clinic Report | Fordham School of Law. (n.d.). https://www.fordham.edu/school-of-law/experiential-education/clinics/news/presidential-succession-clinic-report/ ↵

- Twenty-fifth amendment (1965) –. (2019, January 15). Annenberg Classroom. https://www.annenbergclassroom.org/resource/our-constitution/constitution-amendment-25/ ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Sullivan, K. (2021, November 19). For 85 minutes, Kamala Harris became the first woman with Presidential Power | CNN politics. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2021/11/19/politics/kamala-harris-presidential-power/index.html ↵

- Ibid. at 6th para. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Congressional Resource Service. (2021, February 5). The Twenty-Fifth Amendment: Sections 3 and 4—Presidential Disability. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/IF11756.pdf ↵

- House approves 25th amendment resolution against trump, pence says he won’t invoke. (2021, January 12). House Approves 25th Amendment Resolution Against Trump, Pence Says He Won’t Invoke. https://www.npr.org/sections/trump-impeachment-effort-live-updates/2021/01/12/955750169/house-to-vote-on-25th-amendment-resolution-against-trump ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Congressional Resource Service. (2021, February 5). The Twenty-Fifth Amendment: Sections 3 and 4—Presidential Disability. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/IF11756.pdf ↵

- Presidential Succession Clinic Report | Fordham School of Law. (n.d.). https://www.fordham.edu/school-of-law/experiential-education/clinics/news/presidential-succession-clinic-report/ ↵