Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student will be able to:

- Define communication.

- Describe the communication assumptions.

- Identify the five forms of communication.

- Illustrate similarities and differences amongst the five forms of communication.

- List some career options for students who study communication.

Definitions of Communication

Before we dive into the discipline of speech communication, it is imperative to have a shared understanding of the word communication. In his book Democracy and Education, John Dewey, educator, philosopher, and not the founder of the Dewey decimal system stated,

“Society not only continues to exist by transmission, by communication, but it may fairly be said to exist in transmission, in communication. There is more than a verbal tie between the words common, community, and communication. Men [sic] live in a community in virtue of the things which they have in common; and communication is the way in which they come to possess things in common” (1916, p. 5).

For our purposes, we will defer to John Dewey and employ his definition of communication. According to Dewey (1916) “communication is a sharing of experience till it becomes a common possession” (p. 11). Understandably, recognizing and using a definition from 1916 may “feel” dated. However, compare Dewey’s definition to more recent definitions published in print books and you will see that his 100 year old definition has not changed dramatically.

“Communication is the process of creating meaning through symbolic interaction” (Adler, Rodman, & du Pré, 2020, p. 2).

“Communication is the process of using messages to generate meaning” (Child, 2019, p. 4).

“Communication is a transactional process of sharing meaning with others” (Rothwell, 2020, p. 6).

“Communication is a transactional process using symbols to create (shared) meaning” (Turner & West, 2019, p. 4).

“Communication is the process through which we express, interpret, and coordinate messages with others” (Verderber, Sellnow, & Verderber, 2015, p. 4).

“Communication is a complex process through which we express, interpret, and coordinate messages with others” (Verderber, Sellnow & Verderber, 2017, p. 5).

More than likely, you can clearly see that the understanding of communication has not dramatically changed since Dewey’s (1916) description. A brief overview of the aforementioned definitions reveals a few assumptions about communication that require more explanation. The following section will discuss four assumptions:

- Communication is a process.

- Communication is about sharing.

- Communication uses symbols to generate messages or meaning.

- Communication is a phenomenon.

Communication Assumptions

Communication is a Process

Throughout this textbook, you are often going to come across the word “process.” Before you go any further into this textbook, it is encouraged that you have an understanding of the construct of “process.” According to the online version of Merriam-Webster Dictionary.com, process, as a noun is defined as “(a) a natural phenomenon marked by gradual changes that lead toward a particular result; (b) a series of actions or operations conducing to an end,” yet as a verb process is defined as “to subject to or handle through an established usually routine set of procedures.” Thus, the word “process,” for our purposes is assumed to be understood as a “series of steps leading to a determined end.”

Communication is about Sharing

As you consider this assumption, first imagine yourself in the act of “sharing” with another. When you “share” with another, what physical action is required and what mental motivation is required? Perhaps you imagine yourself giving an object to another person and the other person takes the object. Although that is a good start, what other actions must take place for sharing to occur? Perhaps you imagine that the other person gives back the object to the first person. Again, yes, this cyclical giving and taking of an object is part of sharing, but what else is required in the action of sharing?

Consider what thinking or motivation is required to influence the giving and taking of an object. What must both people “accept,” in terms of their thinking, for the action of sharing to occur? Discuss the action of sharing with another. What is necessary for “sharing” to occur?

Communication Uses Symbols to Generate Meaning

Sociologist and rhetorician Kenneth Burke (1966, in Gusfield, 1989) writes, “man is the symbol-using animal” (p. 56). According to Burke, and his theory of symbolic interaction, human beings are unique from all other animals in that we use symbols to create our understanding of time and place, and those same symbols assist in understanding our feelings about both. Often, symbols are easily recognized, in a physical sense, as a road sign informing you to “Stop!.” or “Caution! Slippery When Wet!,” or “Yield,” but those “signs” only make sense to humans because we have previous interactions with other significant symbols. George Mead (1922) pens, “the significant symbol is the gesture, the sign, the word which is addressed to the self when it is addressed to another individual, and is addressed to another, in form to all other individuals, when it is addressed to the self” (p. 162). Simply put, since the time and place of your birth, you have been learning how to communicate by an exhaustive accumulation of symbols and your interactions with said symbols. Clearly, symbolic interactionism is a complex theory that explains human communication and diving too deeply into it’s nuances is not the focus of this book, but as students of communication, and perhaps a future communication scholar, having an understanding of how humans have used, continue to use, and will use symbols in our social evolution is significant in your studies.

Herbert Blumer wrote the seminal book on Symbolic Interactionism in 1969. His book, aptly named Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method thoroughly details the theory of how humans use symbols to interact with self, others, and context. As Blumer (1969) writes, “group life necessarily presupposes interaction between the group members; or, put otherwise, a society consists of individuals interacting with one another” (p. 7). Furthermore, as Blumer continues the interaction of individuals is strongly influenced by the mutual understanding of verbal and nonverbal symbols in a respective context. For example: Imagine walking down the hallway and seeing a person approaching you.

Scenario 1: An older man. Gray in his beard, balding, dressed like a teacher. Makes eye contact and says, “Good morning” as you pass by.

Your response? Your feelings?

Scenario 2: A young woman. 18-20. Dressed in typical fashion. Makes eye contact and says, “Good morning” as you pass by.

Your response? Your feelings?

More than likely, you have experienced both of these innocuous interactions and have had a response to both. We don’t respond to people the same way, do we? Furthermore, our feelings about both interactions are not replicated due to your previous interactions with similar symbols. As you can note, both people performed the same action with you and both said the same words to you, but as symbolic interactionism will posit: your meaning of the messages will differ due to your previous interactions with learned symbols embedded in various communicative contexts.

Communication is a Phenomenon

To continue with the philosophical components of the communication discipline, it is also important to assume that communication is phenomenological. Merleau-Ponty (1945) writes, “phenomenology is the study of essences” (p. vii). Since Merleau-Ponty’s (1945) definition is a tad too “philosophical” it is necessary to better understand what is meant by communication as a phenomenon. Again, utilized the online version of the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, we can define phenomenon as “an observable fact or event or object or aspect known through the senses rather than by thought or intuition.” Therefore, a phenomenon is something that you can see, hear, taste, touch or smell that creates understandable meaning to you. Take for example, the smell of cookies. Your nose smells “cookie,” and now you can, in your imagination, “see” a cookie, “taste” a cookie, “feel” a cookie….although it’s not actually there. This is a nature of a phenomenon.

By nature, communication is phenomenological. You can hear words, although you can’t “see them.” You can hear words and you can “feel” a feeling. You can be “listening” to your favorite song in your car and then “see” police lights in your mirror and “feel” your feelings change. Your ability to see, hear, touch, taste, and smell “things” and your subsequent ability to make meaning associated with those sensory messages demonstrates the phenomenological nature of communication.

Forms of Communication

The field of communication has become quite large and vast. Scholars in this discipline study health communication, sports communication, conflict management, political communication, marketing, and the list goes on and on and on and will continue to grow because as Dewey states, “Society not only continues to exist by transmission, by communication, but it may fairly be said to exist in transmission, in communication” (1916, p. 5). Communication is at the very center of each and every aspects of your personal and social life. Therefore, as communication is “all around us,” many scholars in this field have found that not all forms of communication are alike. And so, in time, communication scholars, have come to agree on five main “types,” or “forms” or “genres” of communication, and those are:

- Intrapersonal communication.

- Interpersonal communication.

- Small group communication.

- Public communication.

- Mass communication.

As you read this book and as you continue through this course with your instructor, you may find one of these forms particularly interesting. If this is you, reach out to your instructor and ask about what other courses your college or university offers that will teach you about the myriad, and perhaps countless ways that you can study this discipline deeper and with more breadth. The following section will discuss the similarities and differences amongst each form of communication, including its definition, level of intentionality, goals, and contexts.

Intrapersonal Communication

Intrapersonal communication, or sometimes referred to as “self-talk,” is communication with oneself using internal vocalization or reflective thinking (Sellnow et al, 2018, p. 23). Like other forms of communication, intrapersonal communication is triggered by some internal or external stimulus. We may, for example, communicate with oneself about what to eat after seeing another person take a bite of a sandwich or when we smell the unique odor of a freshly extinguished, smoldering, match. Unlike other forms of communication, intrapersonal communication takes place inside our heads. As will be explained later, the other forms of communication must be received and perceived by another person to meet the criterion for communication.

Intrapersonal communication is communication with ourselves that takes place in our heads.

Sarah – Pondering – CC BY 2.0.

In his 1989 book, Meaning and Mind: An Intrapersonal Approach to Human Communication, author Leonard Shedletsky writes,

It is one thing to read about selective attention and quite another to “catch” oneself shifting attention in the course of a conversation; to know that words can be ambiguous, and to experience ambiguity and alternative interpretations in communication; to learn about emotions, and to observe one’s own emotional triggers and their effects upon reasoning. (See William James, 1890.)

Simply put, intrapersonal communication is a very important aspect of human communication. And as Jemmer (2009) states,

“the [intrapersonal communication] situation is complicated by the fact that the expressions of internal dialogue are manifold and the elements of inner speech are found in all our conscious perceptions, actions, and emotional experiences, where they manifest themselves as verbal sets, instructions to oneself, or as verbal interpretations of sensations and perceptions. This renders inner speech a rather important and universal mechanism in human consciousness and psychic activity.” (p. 39)

It is rare to find courses devoted to the topic, and it is generally separated from the remaining four types of communication. This is probably due to the fact that intrapersonal communication seems to be better suited to individuals interested in the study of human psychology rather than those of us interested in the study of human communication. The main distinction of intrapersonal communication as opposed to the other genres is “the triad of “sender-[message]-receiver” [are] all located in the same individual” (Jemmer, 2009, p. 38).

Interpersonal Communication

Interpersonal communication is communication between two people whose lives mutually influence one another. Interpersonal communication, or sometimes referred as “dyadic communication” builds, maintains, and ends our relationships, and we spend more time engaged in interpersonal communication than the other forms of communication. Interpersonal communication occurs in various contexts and is addressed in subfields of study within communication studies such as intercultural communication, organizational communication, health communication, and computer-mediated communication. After all, interpersonal relationships exist in all those contexts.

Interpersonal communication can be planned or unplanned, but since it is interactive, it is usually more structured and influenced by social expectations than intrapersonal communication. Interpersonal communication is also more goal oriented than intrapersonal communication and fulfills instrumental and relational needs. In terms of instrumental needs, the goal may be as minor as greeting someone to fulfill a morning ritual or as major as conveying your desire to be in a committed relationship with someone. Interpersonal communication meets relational needs by communicating the uniqueness of a specific relationship. Since this form of communication deals so directly with our personal relationships and is the most common form of communication, instances of miscommunication and communication conflict most frequently occur here (Dance & Larson, 1972). Couples, bosses and employees, and family members all have to engage in complex interpersonal communication, and it doesn’t always go well. In order to be a competent interpersonal communicator, you need conflict management skills and listening skills, among others, to maintain positive relationships.

Small Group Communication

Group communication is communication amongst three or more people, who feel a sense of belonging, either influence or are willing to be influenced and all of whom are working towards a common shared goal. You have likely worked in groups at work, in school, and in extra curricular activities. Furthermore, if you are like most people, group communication is not something you enjoy and/or are very good at it. Even though it can be frustrating, group work in an academic setting provides useful experience and preparation for group work in professional settings. Organizations have been moving toward more team-based work models, and whether we like it or not, groups are an integral part of people’s lives. Therefore, the study of group communication is valuable in many contexts.

Since many businesses and organizations are embracing team models, learning about group communication can help these groups be more effective.

RSNY – Team – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Group communication is usually intentional and may include formal group rules rather than assumed norms that tend to drive most communication. Group communication is often task focused, meaning that members of the group work together for an explicit purpose or goal that affects each member of the group. Goal-oriented communication in interpersonal interactions usually relates to one person; for example, I may ask my friend to help me move this weekend. Goal-oriented communication at the group level usually focuses on a task assigned to the whole group; for example, a group of people may be tasked to figure out a plan for moving a business from one office to another.

You know from previous group experience that more communicators usually leads to more conflict. Some of the challenges of group communication relate to task-oriented interactions, such as deciding who will complete each part of a larger project. But many challenges stem from relational-oriented conflict amongst the group membership. Since group members also communicate with and relate to each other interpersonally, may have preexisting relationships, or may develop them during the course of group interaction, the tenets of interpersonal communication are multiplied due to the sheer volume of communicated messages. Chapter 13 “Small Group Communication” and Chapter 14 “Leadership, Roles, and Problem Solving in Groups” of this book, which deal with group communication, will help you learn how to be a more effective group communicator by learning about group theories and processes as well as the various roles that contribute to and detract from the overall functionality of a group.

Public Communication

Public communication is a sender-focused form of communication in which one person is typically responsible for conveying information to an audience. Public speaking is something that many people fear, or at least do not enjoy.

But, just like group communication, public speaking is an important part of our academic, professional, and civic lives. When compared to interpersonal and group communication, public communication is the most intentional, most formal, and most goal-oriented form of communication we have discussed.

Public communication, at least in Western societies, is predominately sender-focused. It is precisely this formality and focus on the sender that makes many new and experienced public speakers anxious at the thought of facing an audience. One way to begin to manage anxiety toward public speaking is to begin to see connections between public speaking and other forms of communication with which we are more familiar and comfortable. Despite being formal, public speaking is very similar to the conversations that we have in our daily interactions. For example, although public speakers do not necessarily develop individual relationships with audience members, they still have the benefit of being engaged face-to-face, thus the speaker is able to receive verbal and nonverbal feedback. Later in this chapter, you will learn some strategies for managing speaking anxiety, since presentations are a requirement in the basic speech at College of DuPage. In Chapter 9 “Preparing a Speech”, Chapter 10 “Delivering a Speech”, Chapter 11 “Informative and Persuasive Speaking”, and Chapter 12 “Public Speaking in Various Contexts”, you will learn how to choose an appropriate topic, research and organize your speech, effectively deliver your speech, and evaluate your speeches in order to improve.

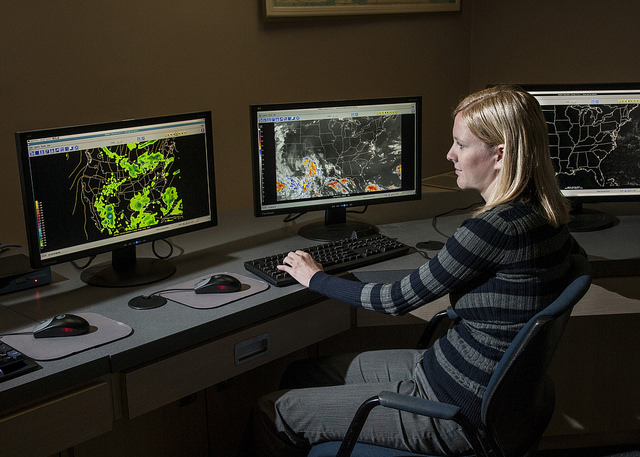

Mass Communication

Public communication becomes mass communication when it is transmitted to many people through print or electronic media. Print media such as newspapers and magazines continue to be an important channel for mass communication, although they have suffered much in the past decade due in part to the rise of electronic media. Television, websites, blogs, and social media are mass communication channels that you probably engage with regularly. Radio, podcasts, and books are other examples of mass media. The technology required to send mass communication messages distinguishes it from the other forms of communication. A certain amount of intentionality goes into transmitting a mass communication message since it usually requires one or more extra steps to convey the message. This may involve pressing “Enter” to send a Facebook message or involve an entire crew of camera people, sound engineers, and production assistants to produce a television show. Even though the messages must be intentionally transmitted through technology, the intentionality and goals of the person actually creating the message, such as the writer, television host, or talk show guest, vary greatly. The president’s State of the Union address is a mass communication message that is very formal, goal oriented, and intentional, but a president’s verbal gaffe during a news interview is not.

Technological advances such as the printing press, television, and the more recent digital revolution have made mass communication a prominent feature of our daily lives.

Savannah River Site – Atmospheric Technology – CC BY 2.0.

Mass communication differs from other forms of communication in terms of the personal connection between participants. Even though creating the illusion of a personal connection is often a goal of those who create mass communication messages, the relational aspect of interpersonal and group communication isn’t inherent within this form of communication. Unlike interpersonal, group, and public communication, there is no immediate verbal and nonverbal feedback loop in mass communication. Of course you could write a letter to the editor of a newspaper or send an e-mail to a television or radio broadcaster in response to a story, but the immediate feedback available in face-to-face interactions is not present. With new media technologies like Twitter, blogs, and Facebook, feedback is becoming more immediate. Individuals can now tweet directly “at” (@) someone and use hashtags (#) to direct feedback to mass communication sources. Many radio and television hosts and news organizations specifically invite feedback from viewers/listeners via social media and may even share the feedback on the air.

The technology to mass-produce and distribute communication messages brings with it the power for one voice or a series of voices to reach and affect many people. This power makes mass communication different from the other levels of communication. While there is potential for unethical communication at all the other levels, the potential consequences of unethical mass communication are important to consider. Communication scholars who focus on mass communication and media often take a critical approach in order to examine how media shapes our culture and who is included and excluded in various mediated messages. We will discuss the intersection of media and communication more in Chapter 15 “Media, Technology, and Communication” and Chapter 16 “New Media and Communication”.

“Getting Real”

What Can You Do with a Degree in Communication Studies?

You’re hopefully already beginning to see that communication studies is a diverse and vibrant field of study. The multiple subfields and concentrations within the field allow for exciting opportunities for study in academic contexts but can create confusion and uncertainty when a person considers what they might do for their career after studying communication. It’s important to remember that not every college or university will have courses or concentrations in all the areas discussed next. Look at the communication courses offered at your school to get an idea of where the communication department on your campus fits into the overall field of study. Some departments are more general, offering students a range of courses to provide a well-rounded understanding of communication. Many departments offer concentrations or specializations within the major such as public relations, rhetoric, interpersonal communication, electronic media production, corporate communication. If you are at a community college and plan on transferring to another school, your choice of school may be determined by the course offerings in the department and expertise of the school’s communication faculty. It would be unfortunate for a student interested in public relations to end up in a department that focuses more on rhetoric or broadcasting, so doing your research ahead of time is key.

Since communication studies is a broad field, many students strategically choose a concentration and/or a minor that will give them an advantage in the job market. Specialization can definitely be an advantage, but don’t forget about the general skills you gain as a communication major. This book, for example, should help you build communication competence and skills in interpersonal communication, intercultural communication, group communication, and public speaking, among others. You can also use your school’s career services office to help you learn how to “sell” yourself as a communication major and how to translate what you’ve learned in your classes into useful information to include on your resume or in a job interview.

The main career areas that communication majors go into are business, public relations / advertising, media, nonprofit, government/law, and education.[1] Within each of these areas there are multiple career paths, potential employers, and useful strategies for success. For more detailed information, visit http://whatcanidowiththismajor.com/major/communication-studies.

- Business. Sales, customer service, management, real estate, human resources, training and development.

- Public relations / advertising. Public relations, advertising/marketing, public opinion research, development, event coordination.

- Media. Editing, copywriting, publishing, producing, directing, media sales, broadcasting.

- Nonprofit. Administration, grant writing, fund-raising, public relations, volunteer coordination.

- Government/law. City or town management, community affairs, lobbying, conflict negotiation / mediation.

- Education. High school speech teacher, forensics/debate coach, administration and student support services, graduate school to further communication study.

- Which of the areas listed above are you most interested in studying in school or pursuing as a career? Why?

- What aspect(s) of communication studies does/do the department at your school specialize in? What concentrations/courses are offered?

- Whether or not you are or plan to become a communication major, how do you think you could use what you have learned and will learn in this class to “sell” yourself on the job market?

Key Takeaways

- Getting integrated: Communication is a broad field that draws from many academic disciplines. This interdisciplinary perspective provides useful training and experience for students that can translate into many career fields.

- Communication is the process of generating meaning by sending and receiving symbolic cues that are influenced by multiple contexts.

- Ancient Greeks like Aristotle and Plato started a rich tradition of the study of rhetoric in the Western world more than two thousand years ago. Communication did not become a distinct field of study with academic departments until the 1900s, but it is now a thriving discipline with many subfields of study.

-

There are five forms of communication: intrapersonal, interpersonal, group, public, and mass communication.

- Intrapersonal communication is communication with oneself and occurs only inside our heads.

- Interpersonal communication is communication between people whose lives mutually influence one another and typically occurs in dyads, which means in pairs.

- Group communication occurs when three or more people communicate to achieve a shared goal.

- Public communication is sender focused and typically occurs when one person conveys information to an audience.

- Mass communication occurs when messages are sent to large audiences using print or electronic media.

Exercises

- Getting integrated: Review the section on the history of communication. Have you learned any of this history or heard of any of these historical figures in previous classes? If so, how was this history relevant to what you were studying in that class?

- Come up with your own definition of communication. How does it differ from the definition in the book? Why did you choose to define communication the way you did?

- Over the course of a day, keep track of the forms of communication that you use. Make a pie chart of how much time you think you spend, on an average day, engaging in each form of communication (intrapersonal, interpersonal, group, public, and mass).

Media Attributions

- 1.1.1N

- 1.1.2N

- 1.1.3N

- What Can I Do with This Major? “Communication Studies,” accessed May 18, 2012, http://whatcanidowiththismajor.com/major/communication-studies ↵