Chapter 2 – Other Models for Promoting Community Health and Development

Section 2-1: Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities

-

WHAT IS HEALTHY CITIES/HEALTHY COMMUNITIES?

-

WHY USE HEALTHY CITIES/HEALTHY COMMUNITIES?

-

WHO SHOULD PARTICIPATE IN HEALTHY CITIES/HEALTHY COMMUNITIES?

-

HOW DO YOU USE HEALTHY CITIES/HEALTHY COMMUNITIES?

In this video, Tyler Norris, Vice President of Kaiser Permanente Center for Total Health, discusses the meaning and impacts of community health. “What is a healthy community? What is healthy, and what is a community?” He asks. In this section, we will explore the concepts of defining, creating, and promoting healthy communities.

WHAT IS HEALTHY CITIES/HEALTHY COMMUNITIES?

Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities is a theoretical framework for a participatory process by which citizens can create healthy communities. In 1985, at a conference in Toronto organized by Trevor Hancock, Len Duhl spoke about his long-held conviction that health issues could only be effectively addressed through an inclusive, community-wide approach. Ilona Kickbusch, a World Health Organization (WHO) official who was attending the conference, brought the idea back to her superiors at the WHO European office in Copenhagen. Within a matter of weeks, Duhl and Hancock had been hired as consultants to help WHO and Kickbusch start a Healthy Cities movement in Europe. A year later, the attendees of a WHO conference in Ottawa drafted the Ottawa Charter, the “Constitution” of Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities. In the years since that first conference, the concept has spread to hundreds of large and medium-sized cities on all continents, and has also been used in smaller municipalities and rural communities in both the developing and the developed world. It is now the standard way in which the WHO addresses community health, and it encompasses other community issues as well.

A healthy community, as we discussed above, is one in which all systems work well (and work together), and in which all citizens enjoy a good quality of life. This means that the health of the community is affected by the social determinants of health and development – the factors that influence individual and community health and development.

So, what does the Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities model look like? Unlike PRECEDE/PROCEED, it has no flow chart or diagram, largely because its process may be totally different in different communities.It’s a loosely-defined strategy that asks citizens and officials to make becoming a healthy community a priority, and to pursue that end by involving all community members in identifying and addressing the issues most important to them.

We have created an informal logic model in order to connect you to your Community Tool Box resources that can support your effort to implement Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities.

Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities rests on two basic premises:

A comprehensive view of health. As we’ve been discussing, a comprehensive view of health takes in all the elements of a community’s life, since they affect both individual health and the health of the community itself. The Ottawa Charter lays out the prerequisites for health in communities:

Peace. This can be interpreted to cover both freedom from warfare, and freedom from fear of physical harm.

During the Vietnam War, young black men on the streets of their home neighborhoods in the U.S. were statistically more likely to be killed by gunfire than were young black soldiers in combat. Those home neighborhoods weren’t at peace, by anyone’s definition.

Shelter. Shelter adequate to the climate, to the needs of the occupants, and to withstand extremes of weather.

Education. Education for children (and often adults as well, as in the case of adult literacy) that is free, adequate to equip them for a productive and comfortable life in their society, and available and accessible to all.

Food. Not just food, but enough of it, and of adequate nutritional value, to assure continued health and vigor for adults, and proper development for children.

Income. Employment that provides an income adequate for a reasonable quality of life, and public support for those who are unable to work or find jobs.

A stable ecosystem. Clean air, clean water, and protection of the natural environment.

Sustainable resources. These might include water, farmland, minerals, industrial resources, power sources (sun, wind, water, biomass), plants, animals, etc.

Social justice. Where there is social justice, no one is mistreated or exploited by those more powerful. No one is discriminated against. No one suffers needlessly because she’s poor or ill or disabled. All are treated equally and fairly under the law, and everyone has a voice in how the community and the society are run.

Equity. Equity is not exactly the same thing as equality. It doesn’t mean that everyone gets the same things, but that everyone gets, or has access to, what he needs.

If all of these factors are considered, then health must extend far beyond medical treatment to all aspects of community life.

A commitment to health promotion. Health promotion differs from the more familiar medical models of treatment and prevention. Both of these look at health from a negative point of view: there’s something wrong or potentially wrong, and the medical expert will step in to fix it or head it off. Health promotion looks at it from a positive point of view: you can take positive steps to improve and sustain your well-being.

Health promotion – and we’ll use the term here to mean the promotion of healthy communities as well as healthy individuals – is a key both to the thinking behind the Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities concept, and to actually developing healthy communities. It calls for a commitment on the part of all sectors of the community, particularly government, to promote community health by:

Building healthy public policy. Communities can establish policies that foster the health of the community. According to the Ottawa Charter, such policies are “coordinated action that leads to health, income, and social policies that foster greater equity.” Thus, smoking bans in restaurants, local tax policies that encourage businesses to create jobs, training for police and youth workers to help them communicate with youth and curb youth violence, and strong environmental ordinances might all be seen as healthy public policy. Community support of such policy produces an atmosphere that makes it easier for policy makers to make the right choices, because they know the public is behind them.

Like all elements of a Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities strategy, healthy public policy is about a great deal more than simply fostering individual health – it’s about public policy that fosters a healthy society. That means equity, health for all, and attention to such things as supportive environments (see below).

Len Duhl talks about the fact that most public policy doesn’t deal with real needs, but rather with concerns of economics and power. For public policy to be healthy, it has to reflect reality, rather than what policy makers want to see, or what will get them elected. Objectivity leads to public policy that benefits everyone, not just the influential few.

Creating supportive environments. Community environments run the gamut from the physical to the social to the economic to the political. Some supportive environments can be created by laws or regulations, some by community effort, and some only by changes in attitude (which may or may not be influenced by social and other pressures). Some examples:

The natural environment. Laws and regulations that restore and/or preserve clean air and water; preservation and creation of open space, natural beauty, and wilderness; restrictions on the use and disposal of toxic substances; conservation of natural resources, including plants and animals. All of these can enhance health and reduce stress, provide an aesthetic experience, and affect community life for the better.

The Peak to Peak Healthy Communities Project, based in Nederland, CO, is working on renovating parks and creating a transportation link from downtown to trails and natural areas outside the city.

The built environment. People-friendly design of buildings and spaces (human scale, with pedestrian passageways, gathering places, views, attractiveness, etc.); handicap access; preservation of historic and cultural heritage; cleanliness; safety (lighting, building and bridge design, long views, traffic patterns, bans on the use of toxic materials); good public transportation; traffic-free paths to encourage walking, jogging, and bicycling.

For example, a city that builds or designates traffic-free walking and bike paths will probably see more of its citizens walk and bicycle to work and on errands than one where walking and biking are difficult and dangerous. Davis, California, for instance, has encouraged bicycling since 1960, when it became the first city in the US to paint bike lanes on its streets. It has been able to discontinue its school bus service, because it’s so easy for children to bike, walk, or skate to school on its miles of car-free bike paths.

The economic environment. A healthy economic environment is one where there is work for everyone capable of working, where workers are treated as assets (see directly below) and are paid a living wage, where there is equal economic opportunity for all, where those who can’t work are supported, and where money doesn’t buy political power or immunity from the law.

Bethel New Life, a faith-based, grass roots initiative in the Garfield Park neighborhood of Chicago, started out to rehabilitate derelict housing in the area, using “sweat equity” – i.e., the labor of local residents, who could then exchange their work for part of the cost of the home they had rebuilt. Now, Bethel employs more than 300, mostly local residents, in housing, employment training and job placement, economic development, cultural, family support, and community development programs. Its board is drawn almost wholly from the community, and its programs are responses to voiced community need. Bethel continues to try to build assets and bring greater economic stability to the West Side of Chicago.

The work environment. The work environment should be a source of stimulation, rather than stress. Respect for employees, good safety precautions and procedures, firm rules forbidding harassment or abuse, adequate pay and/or other compensation, humane and fair production expectations and treatment – all contribute to work environments that nurture creativity and enthusiasm, and improve, rather than detract from, both production and workers’ quality of life.

The leisure environment. The work and home environments can provide time for leisure. The community can provide recreational and cultural opportunities to use in that leisure time: museums, parks and beaches, cultural and sports events, libraries, etc.

The social environment. A healthy community encourages social networks, provides gathering places where people from all parts of the community may mingle, nurtures families and children, offers universal education and other services, strives to forster non-violent an healthy behavior, invites familiartity and interaction among the various groups that make up the community, and treats all groups and individuals with respect.

The North Quabbin Community Coalition, in north central Massachusetts, was concerned, among other things, with the high incidence of child physical and sexual abuse in the area. A task force on the issue eventually developed into Valuing Our Children, a parent education and family life program, that has trained large numbers of area parents as “parent educators,” and that provides services to area families.

The political environment. In a healthy community, all citizens have a say in how and by whom their community is governed, and have easy access to the information necessary to understand political situations and to make informed political decisions. Political decisions, opinions, and speech are protected. Citizens feel they have the power in the community – that they own it, and can and should control its direction.

Strengthening community action. Communities can encourage and strengthen community action in at least three ways: The first involves encouraging and fostering grass roots planning and action. When issues are identified and addressed by the people affected by them, as well as by others concerned, two things happen: the issues are more likely to be resolved successfully, and the people involved learn how to use their own resources to take charge of their lives and their communities. A second way of strengthening community action is through a commitment from government, community leaders, and other decision makers to encourage action by passing legislation conducive to it, lending public support to it through the media and other communication channels, and including members of all segments of the community in the conception, planning, and implementation of any community initiative. The third is by decision makers and the media ensuring a free and accurate flow of necessary information about the community and community initiatives to all citizens, and providing everyone in the community with learning opportunities about issues and about the quality of life in general.

The latter two of these methods are really top-down conceptions where government and others in power “let” citizens share in the decision-making process. While community members – particularly those with less experience in planning and running projects, or with less education – often need support to learn some necessary skills, the drive for change can and should come from them to begin with. There is a big difference between officials organizing an initiative and inviting citizens to join, and officials approaching citizens with a request to participate in envisioning and organizing an initiative.

Developing personal skills. Healthy communities aid their citizens in gaining the skills necessary to address health and community issues, by providing education and information in school, home (through the media and other sources), work, and community settings. Courses, workshops, billboards and posters, TV and radio ads, newspaper articles, mailings, fliers, community meetings, presentations in social clubs and churches, the use of electronic technology – all might serve to help citizens understand an issue, and make decisions about it.

The education referred to here doesn’t relate only to health and wellness issues and life skills (e.g., parenting). In fact, it could, and does, apply to all learning that touches on topics related to the life of the community – political, social, environmental, and economic issues, for instance. Furthermore, the encouragement and accessibility of lifelong learning is a mark of a healthy community.

Reorienting services. To be useful to a Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities strategy, health and other human and municipal services have to change from an individual- and treatment-centered point of view to one that is community-centered and focuses on the promotion of a healthy community.

It’s not only a matter of reorienting health services, but one of reorienting all services to work together toward the goal of a healthy community. Any community issue has to be viewed through the lenses of both the individual and the community. It takes a village not only to raise a child, but to pull families out of poverty, to create employment, to improve mental health, to stop violence, to safeguard the natural environment, and to create a just and equitable society.

WHY USE HEALTHY CITIES/HEALTHY COMMUNITIES?

There are a number of reasons to consider using the Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities framework in planning and implementing community action:

- Community perspective. Virtually all health and community issues are affected by (or are the direct result of) economic, social, political, and/or environmental factors that operate at the community level. If you don’t deal with those factors, the chances are slim that you’ll be able to resolve the issue you’re concerned with.

- Participatory planning and community ownership. Planning that includes those who will be directly affected by or benefit from any community initiative is more likely to reflect the real needs of the community than planning done only by one group. Furthermore, the participatory nature of the Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities framework means that citizens themselves create initiatives and goals for the community. Those initiatives and goals are theirs – not imposed by those in power or by outside “experts”. As a result, their commitment to the process and to the goals makes them far more likely to support and work for the outcomes they’ve chosen.

- Range of ideas. Citizen participation leads to the presentation and consideration of a greater range of ideas and possibilities, and is therefore more likely to hit upon effective goals and actions.

- Knowledge of the community. Citizen participation taps the community’s wisdom about its own history, relationships, and conflicts, and can thus steer initiatives around potentially fatal pitfalls.

- Community-wide ties. Involving all segments of the community encourages interaction across social, economic, and political lines. Those ties strengthen the community as a whole, change people’s perspectives for the better, increase community-wide cooperation, and can positively transform how the community works.

- Achievable and measurable goals. Although Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities’ ultimate goals are wide and long-term, each goal is achievable in a manageable amount of time, and its successful achievement can be demonstrated. Each success sets the stage for enthusiasm for the next initiative.

- Identification and use of community assets and resources. A Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities initiative depends to a large extent on human, institutional, organizational, environmental, and other assets and resources already available within the community. Through identifying and using these, communities learn that they can create their own positive change, and reshape themselves in the ways they want to.

- Community commitment to the long-term process. Because of the participatory nature of the process, and because it requires recruiting more people at each new phase, it builds an ever-expanding core of people with varied skills, talents, and experience committed to the ideal of building a healthy community and improving the quality of life for everyone. That’s important for sustaining the work indefinitely.

- Community self-image. Through the use of the Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities process, the community comes to think of itself as a healthy community, and is concerned with maintaining that image through addressing issues as they come up. Perhaps more important, it is brought to look at the larger picture as well. Holding out an ultimate goal of a totally healthy community, whether attainable or not, keeps everyone working toward it, and means that planning goes on as a matter of course. The healthy community ideal becomes embedded in the self-image of the community, and people understand that they can take their fate in their own hands and work to improve it. The process itself thus becomes an important element in the definition of a healthy community – one in which citizens work together to identify and solve problems, create and consolidate assets, generate improvements, and raise the quality of life for all.

WHO SHOULD PARTICIPATE IN HEALTHY CITIES/HEALTHY COMMUNITIES?

The easy answer to this question is everyone in the community, and that’s in fact the ideal. In a perfect world, everyone everywhere would participate in some way in creating a healthy community. In the real world, while it’s important to try to involve all sectors of the community, you have to work to involve some particular people and groups if your effort is to be successful. Crucial participants include:

- Elected and appointed officials. Although a Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities initiative should not be top-down, it needs the commitment and backing of those with the power to make things happen. Officials can use the media to publicize the effort, pass laws and regulations (and enforce those already existing) that reinforce it, and throw the weight and resources of government behind it. Without official support, a community-wide effort is more likely to fail.

- Those most affected by the issue. A sure recipe for failure is to try to impose an intervention or initiative on a population “for their own good.” All too often, “experts” – often people who have no real knowledge of the group or its issues – formulate plans that might make perfect sense on paper, but make no sense at all in the actual situation for which they’re proposed. The participation of those affected in identifying the issues to address, developing action plans for addressing them, and implementing and overseeing those plans is absolutely crucial to the success of a Healthy Communities initiative. (This is equally true when the group concerned is the whole community.)

There are, unfortunately, many instances of a group resisting and short-circuiting well-meaning changes because they weren’t part of the planning. The author experienced one as a teacher in Philadelphia, which had, at the time, an innovative and progressive school superintendent. He tried to institute reforms that probably would have improved the lives of teachers students in the system, but he did it without conferring with them. As a result, the teachers simply ignored directives from the central office, the reforms failed, and the superintendent was gone within three years.

- The people who will actually administer and carry out the initiative, or whose jobs or lives will be affected by it. It is both unfair and unwise to expect organization staff, community employees (police, firefighters, Department of Public Works personnel, etc.), business people, and others to throw themselves into carrying out an initiative they had no part in devising. It may have elements that ignore the realities of their jobs or their lives, or that make things harder than necessary for them, and they may be the only people who have the information to understand that. In addition, they may regard it as just another foolish imposition to be gotten around, and do as little as possible to make it effective.

- All the agencies and groups that will need to cooperate and to coordinate their activities in order to implement a community-wide effort. Both the ways in which these groups will work together, and which of them will have responsibility for what have to be part of the planning for any community-wide initiative. Without their full participation, there’s no guarantee that they’ll work together at all, let alone that the methods for their doing so will be simple and efficient.

- Community opinion leaders. These are the people whose opinions others trust, and who lead the community by adopting new ideas and pulling others with them. They are seen as level-headed, smart, and serving the best interests of the community. Some may be current or former members of the groups already listed, and others may be clergy, credible institutional or business people (college presidents or faculty, CEO’s), or just average citizens who are known for their integrity and common sense.

If you can gain the participation of members of all these groups, it is more likely that everyone else will follow. If you can’t get people from all these groups to buy in at the outset, an alternative is educating them about the process and persuading them to join it, while you continue to recruit other participants. Ultimately, the combination of education and your momentum will bring in those who were initially reluctant. That may take time and patience, but it’s worth the effort – it can easily mean the difference between a successful long-term Healthy Community movement and a dead-on-arrival, failed attempt at one.

HOW DO YOU USE HEALTHY CITIES/HEALTHY COMMUNITIES?

Because the Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities framework is just that – an intellectual framework, rather than a prescription – there is no step-by-step instruction for employing it. It is meant to be adapted to the different needs of different communities. There are, however, necessary components of any Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities initiative:

- Create a compelling vision based on shared values. As with virtually any process that involves planning – and particularly participatory planning – the first step is to create a vision that defines the effort to be made. That vision may be broad (“A community that is truly just and equitable”) or more specific (“A community where every potential worker in the community can find employment that offers a living wage and acceptable working conditions”). Whatever the case, the vision must be compelling – one that motivates people to work for its realization. It must be founded in those values that they hold in common, and must be widely shared and recognized as legitimate and desirable.( Proclaiming Your Dream: Developing Vision and Mission Statements.)

In Orlando, Florida, the Healthy Community Initiative began with meetings of a few influential people. As they learned about healthy communities, the convened a group of about 160, representing all sectors of the city’s population – citizens of all races and economic levels, organizations and institutions, city government, other groups – to hash out a vision. That group, in turn, conducted citizen focus groups and public meetings to hear and understand citizens’ concerns. Ultimately, they drafted a vision, based on their own discussions and the input of hundreds of others from all walks of life, that contained 14 statements about what Orlando should be. That vision became the foundation of the initiative.

- Embrace a broad definition of health and well-being. Health must be seen as not merely the physical health of individuals, but the creation and nurturing of those factors leading to health named in the Ottawa Charter (peace, shelter, education, income, food, a stable ecosystem, sustainable resources, social justice, and equity). A truly healthy community encompasses – or works toward – all those elements and more.

- Address quality of life for everyone. The key word here is “everyone.” A Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities initiative should be aimed at improving the quality of life for all groups and individuals in the community, not just those in a particular target group or those who began the initiative.

- Engage diverse citizen participation and be citizen-driven. Initiatives should be originated, planned, and implemented with the full participation of citizens from all racial, ethnic, and socio-economic groups and all walks of life. Citizens themselves, rather than a government agency or experts of some sort, should be the force behind both the direction and the implementation of any community initiative.

- Seek multi-sectoral membership and widespread community ownership. All sectors of the community – government, the business and non-profit communities, health care, education, faith communities, cultural institutions and the arts, target populations, and ordinary citizens – should be represented in an initiative, and the community should feel that it created the initiative and owns it.

In many places in this and other sections of the Community Tool Box, we refer to “ownership” of an initiative or intervention or organization. In most cases, what we mean is that those who take part in creating and/or running such an endeavor feel that it belongs to them. It was their idea, and they therefore see themselves as not only supportive of it, but responsible for it.

True ownership can rarely, if ever, be attached to actions or ideas that are imposed, by others who “know better” or have more power. It comes from within, from the feeling that you’ve made a choice based on your best judgment. That’s why the inclusion of people from all sectors of the community is so important to a successful Healthy Cities/ Healthy Communities process. At the end, perhaps after a lot of argument and soul-searching, participants feel that they’ve had a hand in creating something important that will result in better lives for everyone in the community. There’s no substitute for that feeling to ensure their doing all they can to make their creation work.

- Acknowledge the social determinants of health and the interrelationship of health with other issues (housing, education, peace, equity, social justice). The research on the social determinants of health points to three overarching factors:

- Socioeconomic equity. For developed countries, the economic and social equality within the society or a given community is a greater determinant of death rates and average lifespan than the country’s position with regard to others. The size of the income gap between the most and least affluent segments of the society or community is tremendously important, and determines to a large extent whether people get what they need.

- Social connectedness. Many studies indicate that “belonging” – whether to a large extended family, a network of friends, a social or volunteer organization, or a faith community – is related to longer life and better health, as well as to community participation.

- Sense of personal efficacy. This refers to people’s sense of control over their lives. People with a higher sense of efficacy tend to live longer, maintain better health, and participate more vigorously in community affairs and politics.

Like the Ottawa Charter, the World Health Organization, in its publication The Solid Facts, recognizes the need to break these factors down into more manageable pieces. It lists ten factors that affect health and life expectancy, and advocates addressing each within a coherent program that looks at all of them within a society. These ten factors are:

- The social gradient (equity)

- Stress

- Early life

- Social exclusion (the opposite of social connectedness)

- Work

- Unemployment

- Social support

- Addiction

- Food

- Transport

- Address issues through collaborative problem-solving. Given a diverse group, there are bound to be disagreements and conflicts. These should be viewed as opportunities, rather than roadblocks, and people should be encouraged and helped to work together to reach creative solutions.

- Focus on systems change. To be successful, a Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities initiative has to be active, rather than reactive. It’s not enough to “fix” a problem: your goal is to eliminate the causes of that and other problems and improve the long-term quality of life in the community in the process.

In order to address causes, you have to concentrate not on individual problems, but on improving and changing systems – the ways in which the community operates, and the attitudes, assumptions, and policies behind them. That includes identifying, using, and strengthening the assets the community already possesses, as well as changing the systems that pose problem

- Build capacity using local assets and resources. All communities, no matter how troubled, have great real and potential strengths. These vary from community to community, but could include:

Individuals with the talents, skills, leadership, and passion to work to change the community for the better.

Individuals, businesses, and foundations that can provide material resources – money, space, etc. – to a community effort.

- Institutions – libraries, schools, hospitals, houses of worship – that have the capacity to act as both resources for and agents of change.

- Community-based and other organizations whose mission is to work for the betterment of the whole community.

- Governments and individual government officials that can add both official support and legal and regulatory power to an initiative.

- Human resources – the skills and work ethic of the community’s work force, for example.

- Natural and other environmental resources – open space, clean air and water, wilderness, fisheries, historic sites or buildings, housing stock.

- Perhaps most important, the potential for all these individuals, groups, and resources to be joined in a coordinated pursuit of a common vision.

- At least some of these and other assets already exist in virtually every community – usually to a far greater extent than most citizens realize until they start looking for them. They must be identified and included in a Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities effort.

- Measure and benchmark progress and outcomes. Whatever you’re doing, whether it’s a PR campaign or a complex behavioral intervention, you have to monitor and evaluate it in order to be sure that it’s effective. That means setting objectives – benchmarks – to indicate your progress along the road to your goal, and defining clearly the outcome you’re aiming for. Regularly monitoring what you’re doing is crucial, because it allows you to spot problems or inadequacies in goals, methods, procedures, communication, etc. and correct them before they derail your initiative entirely. Even more important, regular monitoring allows you to change what you’re doing to respond to changes in circumstances and community needs, so that you’re always addressing current reality. Communities are dynamic: they develop and change, sometimes in short periods. Your initiative has to be dynamic, too, especially if you expect it to continue for the long term.

IMPLEMENTING A HEALTHY COMMUNITIES STRATEGY

How do you actually put these components together to create a healthy community? There’s no one way to do that – it depends on your community, the issues you want to address, and the ideas and capacities of the groups and individuals that participate in the Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities process. There are, however, some basic procedures that, at least in outline, should be common to any Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities initiative.

- Assemble a diverse and inclusive group. To begin a Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities initiative, people from all parts of the community have to come together to hammer out a vision. That group, as we’ve been saying throughout this section, should be representative of everyone in the community, so that whatever it decides will be seen as legitimate by just about everyone, and will be owned by the community.

Someone has to start the process. That may be a charismatic or persistent individual, an organization, a coalition, or a government office or agency. Whoever it is should be simply a convener, and not necessarily expect to lead over the long term. Leaders should be chosen by the group itself as it forms, and they should be collaborative ( Collaborative Leadership.)

This is not to say that a Healthy Communities effort doesn’t need leadership. Quite the contrary – leadership and structure are necessary for any successful effort. But leadership should be collaborative and arise from the community. The leader may be an individual, or two, or a larger group. Whatever the situation, the leadership should be one of an equal among equals, and decision-making should be the province of the whole group. That’s how a participatory process works.

It is assumed that all the other steps listed here will also be carried out by an inclusive group, and that all sectors of the community – including those affected and individual citizens – will be represented and have decision-making power. The group may change from step to step or over time, but should remain inclusive and participatory.

- Generate a vision. A vision of how the community should be, based not on a single issue, but on values shared among all participants and on a high quality of life for everyone in the community, is needed to motivate and inspire participants and to guide the initiative over the long term. Generating such a vision may take time and a great deal of discussion, but it’s absolutely necessary for a successful effort.

- Assess the assets and resources in the community that can help you realize your vision, and the issues that act as barriers to it. Placing assets first is not just an accident here. A Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities initiative is best served by looking at the community through a positive lens, and asking first what’s right with it, rather than what’s wrong with it. The initiative then becomes an exercise in community health promotion, instead of the treatment of a diseased community. Taking a positive perspective affects for the better the attitudes of everyone involved, the community’s self-image, and the perception of whether or not realizing your vision is possible. By the same token, it’s important to be honest and clear-eyed about issues and problems in the community. Once they’ve been identified, they have to be acknowledged and understood, so they can be addressed at some point in the process.

- Choose a first issue to focus on. The best way to sink a long-term initiative is to try to accomplish all your goals at once. It’s vital to choose one issue – or in some cases, perhaps, two or three – to attack, and to make it one that can be resolved, so that your first effort leads to success.

What the issue is doesn’t matter, except in that it must be one chosen by citizens as important to them, and must be one that is specific enough to be resolvable. Len Duhl talks about the process in a 1993 interview by Joe Flower in Healthcare Forum Journal.

The first thing that happens when the Healthy Cities program develops in a new place is that some persons assume the responsibility of bringing together all segments of the community to deal with the issues: the business community, the government, the voluntary sector and the citizens themselves. …

Then there are “vision workshops” in which people are asked, “What kind of city do you really want?” My personal surprise is that the clearer I am about what a Healthy City program is, the less likely a community is to develop it. The fuzzier I am in what a Healthy City is, “A Healthy City is what you want to make it,” the greater the odds are that they will start.

The various participants define the program. All I say is that you have to start someplace. You have to begin to look at it in an ecological and systemic way. You have to involve people. You have to start thinking of values of equity and participation. Beyond that, you can start wherever you want.

Some cities start on the environment, on pollution, on smoking, seat belts and the quality of life index. Some have government operations, some have newspapers, big organizations, housing. Barcelona linked it to the Olympics. Glasgow linked it to developing itself as the cultural capital of Europe. It is being done every way.

- Develop a community-wide strategy, incorporating as many organizations, levels, and sectors as possible. Here’s where Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities differs most from many logic models and other methods that are clear on exactly how to go about planning and carrying out an initiative. Rather than offering a step-by-step process, HC might use any participatory planning process that incorporates a community-wide approach and that looks at all the possible areas that might affect the issue chosen. Thus, you might use VMOSA, PRECEDE/PROCEED, or some variant, or a less structured process – whatever seems appropriate and works for your community.

It is important, however, that your plan result in a community-wide, multi-pronged approach. If your focus is on youth violence, for instance, it should involve some sort of action or supportive function by local government, parents and parent advocates, schools, law enforcement, the court system, welfare, agencies that deal with youth and families, physical and mental health services, Family Planning, the media, adult literacy (dropouts), and potentially or formerly violent youth and their victims. All of these groups and individuals should be working together as a team, each referring youth to other appropriate services or agencies among them, and all coordinated and collaborating in their operation. The focus should be on changing the systems that make a problem possible, or that present barriers to the ideal the community is working toward.

- Implement the plan. Once again, this should involve a community-wide effort. Any oversight of the implementation should include a broad range of individuals and groups, representing a cross-section of the community.

- Monitor and adjust your initiative or intervention. Once you’ve implemented your plan, it’s crucial to evaluate the effectiveness of both your process (Are you doing what you set out to do?) and your results (Are you reaching your benchmarks? Are you having the planned effect on the issue?) If an evaluation gives unsatisfactory answers to any of these questions, you can revisit the issue, determine the reasons your plan isn’t working well, and change it accordingly.

- Establish new systems that will maintain and build on the gains you’ve made. Once you’ve reduced youth violence, for example, you still have to do whatever is necessary to make sure it doesn’t rise again, and that it continues to decline. (What’s the ultimate goal here? Is there an acceptable level of youth violence?) That may mean setting up new organizations or programs, working to change or cement changes in community attitudes and procedures, redesigning school curricula, working regularly with the media – whatever it takes to sustain progress.

- Celebrate benchmarks and successes. Public celebration of achievements not only energizes those who have been working toward them, but informs the community that the drive toward a healthy community is moving forward successfully. It helps to establish the idea of a healthy community in the public mind, and to build a foundation for the continuation of the initiative.

- Tackle the next issue(s). The ultimate goal here is the development of a truly healthy community, which translates to improving the quality of life for everyone in the community. After your first success, it’s time to use your momentum to address another (or more than one other) issue. That may be the removal of a barrier to a healthy community, or it may be the creation of a necessary element of a healthy community. In either case, it means sustaining citizens’ commitment to an ongoing and long-term process, the end result of which is a community controlled by its residents, where all systems work toward the public good.

IN SUMMARY

The health of a community, like that of an individual, depends on far more than freedom from pain or disease. Health, or its lack, for a community is the result of a large number of factors, often intertwined, that span the social, economic, political, physical, and environmental spheres. Virtually any community issue has an effect on, and is affected by, the overall health of the community as a whole, and therefore should be approached in a community context. Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities provides a philosophical framework for an inclusive, participatory process aimed at raising the quality of life for everyone, and creating a truly healthy community.

Two basic premises underlying the Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities concept are a comprehensive view of health and community issues, covering a broad range of factors that contribute to a healthy community; and a commitment to the active promotion of a healthy community, rather than the “treatment” of problems. By addressing the social and other determinants of health and community issues (including the Ottawa Charter’s list of peace, shelter, education, food, income, a stable ecosystem, sustainable resources, social justice, and equity), and by creating appropriate policy and environments, encouraging social action, providing personal skills, and reorienting services to a more wide-ranging approach, communities can foster citizen empowerment and equity.

REASONS FOR ADOPTING THE HEALTHY CITIES/HEALTHY COMMUNITIES APPROACH INCLUDE:

- Its community perspective, leading to a more effective approach to issues.

- Community ownership of any effort, resulting from community participation in its development and implementation.

- The broad range of ideas gained from a participatory process.

- Its access to citizens’ knowledge of the community, helping to avoid pitfalls caused by ignorance of community history and relationships.

- The forging of community-wide and ties that cross economic, social, racial, and other lines.

- Participatory planning leading to solutions that reflect the community’s real needs.

- The adoption of achievable goals, leading to success.

- The identification and use of community assets and resources which both take advantage of what already exists, and teach the community what it can do with its own considerable resources.

- The fostering of community commitment to the process of building a healthy community.

- The creation of a healthy community self-image.

While a Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities process should involve everyone, some particularly important participants include local government and officials; those affected by the issue(s); those who will actually administer and implement the initiative, or whose lives or jobs will be affected by it; any organizations that will be expected to work together; and opinion leaders.

There are 10 important components of a Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities process:

- Create a compelling vision based on shared values.

- Embrace a broad definition of health and well-being.

- Address quality of life for everyone.

- Engage diverse citizen participation and be citizen-driven.

- Multi-sectoral membership and widespread community ownership.

- Acknowledge the social determinants of health and the interrelationship of health with other issues (housing, education, peace, equity, social justice).

- Address issues through collaborative problem-solving.

- Focus on systems change.

- Build capacity using local assets and resources.

- Measure and benchmark progress and outcomes.

Although there is no one step-by-step procedure for a Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities initiative – both the content and the structure of the process depend upon your community’s needs, and, particularly on community decisions – there is, given the ten components above, a reasonable way to approach it in most cases.

- Assemble a diverse and inclusive group.

- Generate a vision.

- Assess the assets and resources in the community that can help you realize your vision, and the issues that act as barriers to it.

- Choose a first issue to focus on.

- Develop a community-wide strategy, incorporating as many organizations, levels, and sectors as possible.

- Implement the plan.

- Monitor and adjust your initiative or intervention.

- Establish new systems that will maintain and build on the gains you’ve made.

- Celebrate benchmarks and successes.

- Tackle the next issue.

PowerPoint: 2.7_0

Online Resources

(The goal in choosing sites here has been to offer a few that give background or general information on Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities, and a few that are the sites of specific programs. Nearly every Healthy Cities site seems to have its own web page, and these can easily be found by searching “healthy cities” and/or “healthy communities.”)

Bethel New Life, a grass roots, church-based urban development effort in the Garfield Park neighborhood of Chicago. A bottom-up initiative that grew organically over many years, responding to the voiced needs of the community. Most staff and board members are community residents.

Mesa County, CO: A case study of community transformation. A grass roots effort that involved the whole community and grew into the Civic Forum; and a more top-down community health assessment.

Community Partners, Inc., an organization deeply involved in the Healthy Communities movement.

Essential State Level Capacities for Support of Local Healthy Communities Efforts, by Peter Lee, Tom Wolff, Joan Twiss, Robin Wilcox, Christine Lyman, and Cathy O’Connor.

Greater Orlando Healthy Communities Initiative. A very top-down effort, started by current and former Junior League presidents, the newspaper editor, the mayor, and other prominent citizens. They involved the community with the help of a consultant.

The Healthy Communities Program in Aiken, South Carolina. A “model” program, focused on infant mortality. A top-down effort, it nonetheless involves the community in planning and input, and has been highly successful not only at reducing infant mortality, but at providing other needed services, many not directly related to health.

Healthy Cities information from WHO Denmark, the godfather of the Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities movement.

The Healthy Cities initiative of Illawarra, Australia.

Healthy People in Healthy Communities, a guide from the US Dept. of Health and Human Services.

The International Healthy Cities Foundation.

Links to numerous articles on Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities from the Change Project. Includes interviews with Len Duhl and Ilona Kickbusch by Joe Flower from the Healthcare Forum Journal.

The Ottawa Charter.

The Peak to Peak Healthy Communities Project, Gilpin County, Colorado.

The Twenty-Fifth Anniversary of Healthy Communities

WHO information on Healthy Cities

Print Resources

Norris, T. (2002). America’s Best Kept Secret: The Healthy Communities Movement. (Reprint by Healthy Communities Massachusetts from the National Civic Review, introduction, Spring, 1997.) Pan American Health Organization. Healthy Municipalities and Communities: Mayors’ Guide for Promoting Quality of Life. Washington, DC.

Public Health, Vol. 115, Nos. 2 and 3 (March/April & May/June, 2000): Focus on Healthy Communities., Vol. 115.

Wilkinson, R., & Michael M. (1998) eds. The Solid Facts: Social Determinants of Health. World Health Organization: Copenhagen.

Section 2-2: Ten Essential Public Health Services

Before you read this section’s information about the Ten Essential Services, we invite you to take a quiz. Answers are provided at the bottom of this page. See how well YOU do!

(1).As you read the front page of the local paper, you notice an alarming article about an outbreak of “disease X” in your community. You read on to learn about the scientifically established cause of “disease X”, and precautionary measures for avoiding exposure.

This valuable information was published as a front-page story because:

a. The local football team lost its game last night

b. The front-page columnist is on vacation

c. State and local health officials and their staff have worked for weeks to gather data, conduct laboratory and statistical tests, generate hypotheses, and collaborate with the media to alert and educate the public about “disease X” as effectively as possible.

(2).On your way into the local grocery store, you notice a flier advertising a toll-free hotline number for enrolling uninsured children in a federally funded health insurance program.

This insurance program is being offered because:

a. The federal government has a budget surplus and is looking for a way to spend it

b. A leading telephone company offered the state health department a great deal on 1-800 numbers

c. Public health professionals have documented the numbers of uninsured children in their states, and worked with federal and state policymakers to institute outreach and “wrap around services” that assure the universal provision of health care.

(3).While shopping in the local mall, you come across a group of nurses offering free blood pressure and cholesterol screenings.

The nurses are offering these screenings because:

a. They need to moonlight

b. They enjoy people watching at the mall

c. They are public health nurses dedicated to community health promotion, including the prevention of heart disease

(4).You and your sweetheart share a romantic dinner at your favorite restaurant. Not only is the meal delicious – you do not get food poisoning!

This enjoyable experience has been brought to you by:

a. The restaurant management

b. Your local health department

c. A joint effort of the restaurant management and your local health department

(5).In an urban area, prevalent liquor stores are slowly being replaced by grocery stores. The mass transit system has been re-routed to guarantee store access to urban residents without vehicles.

This change in the community’s planning and development is probably a result of:

a. The Department of Transportation needing to increase revenue

b. The liquor storeowners deciding that they weren’t doing enough business and moving elsewhere.

c. A collaborative effort of citizens, public health professionals, city planners, and local government officials who share the common goal of preventing substance use and alcoholism among members of their urban community.

(Answers: 1. c; 2. c; 3. c; 4. c; 5. c)

What, besides the same answer, do the quiz scenarios above have in common? They are real life, everyday examples of some of the Ten Essential Public Health Services that public health professionals strive to deliver in the counties and states that they serve.

This Tool Box section will teach you what the Ten Essential Public Health Services are, and illustrate the function of those Services in public health. When you have completed the tool, you will be able to identify under which Essential Service public health activities in your community are implemented. More importantly, we hope that you will understand how the synergy of efforts within all ten Essential Service areas can contribute to the health of your community’s populations.

To help you get started with identifying how the Ten Essential Public Health Services are reflected in day-to-day public health activities, Table 1 below matches five of the Ten Essential Public Health Services with their corresponding quiz scenarios.

Table 1: Examples of How Essential Services Are Reflected in Day-to-Day Public Health Activities

|

Quiz Scenario

|

Essential Public Health Service Implemented

|

|

Informing the public about an epidemiological outbreak investigation in the community

|

“Investigate, diagnose, and address health hazards and root causes”

|

|

Promoting enrollment in a federally subsidized health insurance program

|

“Enable equitable access”

|

|

Health education and health promotion to prevent heart disease

|

“Communicate effectively to inform and educate”

|

|

Maintenance of a sanitary restaurant environment for public well-being

|

“Utilize legal and regulatory actions”

|

|

Shaping health policy, city planning, and transportation routes to create an environment that fosters positive health behavior

|

“Create, champion, and implement policies, plans, and laws”

|

We hope that you want to read on and learn more. But before we discuss each of the Essential Services, we will visit the broader concept of defining the purpose and function of public health.

WHAT IS PUBLIC HEALTH?

As you probably concluded from the quiz scenarios, public health is everywhere – it is a part of the infrastructure that keeps our communities safe and healthy.

Depending on which resource you read, you will find varying definitions of the mission of public health. However, the most current and widely accepted mission definition is:

“Promote physical and mental health, and prevent disease, injury, and disability.”

Public health services may go unnoticed within a community because they are often (but not always) preventive versus reactive. For example, which community service are you more likely to notice – an environmental health specialist inspecting the safety of a local university’s food service establishments, or a fire truck speeding down the street with its lights and sirens on?

Despite having a relatively ‘low profile’ status, public health services play a key role in assuring the health and well being of communities. Throughout the 1900s, the average lifespan of persons in the United States increased by more than 30 years. According to an article by Bunker, Frazier, and Mosteller (1994), 25 years of this are attributable to advances in public health.

WHO IS THE TYPICAL PUBLIC HEALTH PROFESSIONAL?

There really is no “typical” public health professional. The public health workforce in the United States consists of approximately 500,000 individuals with diverse professional training and experience.

- Some are nurses, physicians, or laboratory technicians by training.

- Some are educators, nutritionists, or social workers by training.

- Some are biostatisticians or epidemiologists.

- Others are economists or lawyers.

- Community-based or “grassroots” workers might include concerned parents, grandparents, or civic leaders who volunteer their time.

How do all of these people with a unified purpose but different skills work together successfully to carry out the mission of public health? They have a logic model to consult: the Ten Essential Services of Public Health.

The Ten Essential Services of Public Health differ in some ways from other logic models presented in Chapter 2 of the Tool Box. Other logic models discussed incorporate prescribed processes (e.g., from planning to implementation to evaluation) diagrammed in a flow chart that can then be applied to one priority goal like teen pregnancy prevention. In contrast, there is no prescribed order of implementation for the Ten Essential Services—no flow chart, and no one specific outcome that results from implementing all ten Essential Services. Rather, the Ten Essential Services have the potential to create a comprehensive infrastructure that can provide a supportive context for any public health priority in a community.

Although the more prescriptive logic models may be narrow in scope once applied to one goal, they can also undertake a comprehensive approach within a community. For example, a planning phase might involve stakeholders from non-public health sectors of the community, in an effort to foster the most supportive context for change. This is not unlike the impact of the Ten Essential Services.

You may be wondering,

“Why do people need a logic model for direction if they are already working towards the same mission?”

Because of their diverse backgrounds, some professionals have been trained to follow different paradigms (models) in their specialties. One example is the “medical model” versus the “public health model.” The most significant difference between the two models is that public health activities focus on entire populations, while clinical activities focus on individual patients. Table 2 below summarizes key differences between the paradigms that are typically used to train clinical and public health professionals.

Table 2: Public Health versus Medical Models of Professional Training

|

Public Health Model |

Medical Model |

| Primary focus on population | Primary focus on the individual |

| Public service ethic, tempered by concerns for the individual | Personal service ethic, conditioned by awareness of social responsibilities |

| Emphasis on prevention and health promotion for the whole community | Emphasis on diagnosis, treatment, and care for the whole patient |

| Paradigm employs a spectrum of interventions aimed at the environment, human behavior and lifestyle, and medical care | Paradigm places predominant emphasis on medical care |

The Ten Essential Public Health Services provide a common ground for professionals trained in either paradigm, as well as grassroots workers and non-public health civic leaders, so they can work collaboratively towards fulfilling the public health mission:

“To promote physical and mental health, and prevent disease, injury, and disability.”

Now that you have a better understanding of public health, let’s talk about the origin, purpose, and function of the Ten Essential Public Health Services.

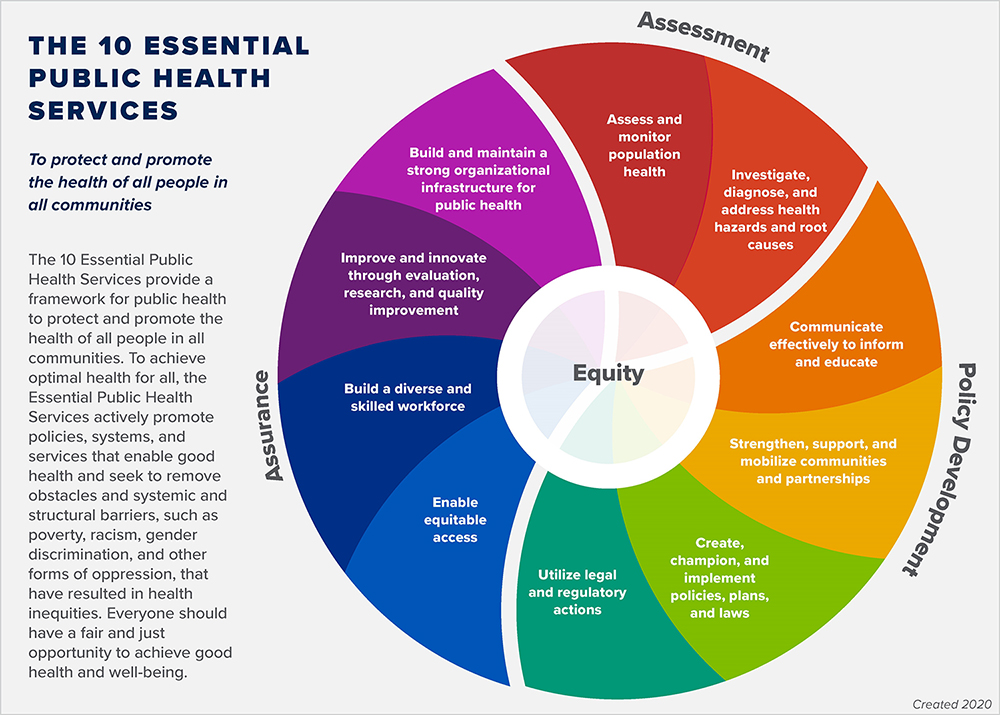

WHAT ARE THE TEN ESSENTIAL PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICES?

From 1988 to the early 1990s, the recognized “core functions” of public health were:

- Assessment

- Policy development

- Assurance

In 1993, with a new presidential administration and federal and state attempts to reform the health care system in the United States, public health leaders decided to set forth a more detailed and utilitarian consensus statement that would “speak with one voice” to public health professionals, the general population, and the policymakers who would shape health care reform.

Public health leaders worked to define a more detailed logic model of core public health functions. The end result was a consensus statement that included the Ten Essential Public Health Services, adopted in 1994.

WHY IS IT IMPORTANT TO IMPLEMENT AND MONITOR THE TEN ESSENTIAL PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICES?

- The Ten Essential Public Health Services are really about actualizing the public health paradigm that we presented in Table 2. Let’s review the key principles involved:

- A primary focus on the population

- A public service ethic, tempered by concerns for the individual

- An emphasis on prevention and health promotion for the whole community

- The paradigm employs a spectrum of interventions aimed at the environment, human behavior and lifestyle, and medical care

The theme of prevention is the most powerful element in the implementation of the Ten Essential Public Health Services.

- Through prevention, countless injuries, illnesses, and even chronic diseases can be avoided.

- Through prevention, lives can be saved.

- Through prevention, health care cost can be contained.

- Through prevention, individuals, their families, and their communities can benefit from the population-based reach of the Ten Essential Public Health Services.

It is important to not only implement but also monitor—or track, assess, and modify, as needed—the Ten Essential Public Health Services. With data or other information about the Services’ costs or expenditures, implementation, and impact, monitoring can contribute to informed policy decisions about public health program development and funding at local, state, and national levels.

HOW ARE THE TEN ESSENTIAL SERVICES USED IN COMMUNITY PRACTICE?

On the pages that follow, each Essential Service is discussed in order from 1 to 10. Each discussion includes a definition of the Service and some examples of national or community practice. Keep in mind that the Services do not necessarily need to be implemented in the “1 – 10” sequence, or even independently.

The Ten Essential Services are independent yet complementary goals for communities to work toward. You should actually strive to implement the services simultaneously in your community as a means of carrying out the mission of public health. However, you may find that you identify with only one or two in terms of your role in your community’s public health initiatives as you read through this section.

Essential Service #1: Assess and monitor population health.

Public health surveillance—the ongoing, systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health related data—is at the core of this Essential Service.

Essential Service #1 encompasses public health activities such as:

- Identification of threats to health and assessment of health service needs;

- Timely collection, analysis, and publication of information on access, utilization, costs, and outcomes of personal health services;

- Attention to the vital statistics and health status of specific groups that are at higher risk than the total population; and

- Collaboration to manage integrated information systems with private providers and health benefit plans.

National level, population-based surveillance systems administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) include:

- The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System;

- National Vital Statistics System;

- National Health Interview Survey; and

- Cancer registries;

You can access CDC data electronically at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. You may not immediately think to use national level data when working at the community level. However, national level surveillance data can provide trend data to use as a benchmark as you assess health status measures (e.g., the number of children immunized prior to entering preschool) in your community. Prior to investing resources and time in a program, it is often necessary to conduct a needs assessment. Community data collected via a needs assessment can be compared to existing data at the national level. If you discover that your community actually has an excellent rate for a health status measure as compared to 75% of the states in the country, you may shift your prevention program priorities to a different measure or target population!

If you do not have the time or resources to conduct your own needs assessment, you can search for community level data in resources including:

- State-level ‘report cards’ on maternal and child health indicators (see the federal Title V Information System with data for all U.S. states and territories).

- School health reports; and

- Law enforcement agency surveillance, such as the number of DUI arrests

Essential Service #2: Investigate, diagnose, and address health hazards and root causes.

Essential Service #2 encompasses public health activities such as:

- Epidemiologic identification of emerging health threats;

- Public health laboratory capability using modern technology to conduct rapid screening and high volume testing;

- Active infectious disease epidemiology programs; and

- Technical capacity for epidemiologic investigation of disease outbreaks and patterns of chronic disease and injury.

At the national level, the United States Department of Health and Human Services oversees the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). The Agency’s overall function is to “serve the public by using the best science, taking responsive public health actions, and providing trusted health information to prevent harmful exposures and disease related to toxic substances.”

Via grants and cooperative agreements, ATSDR provides funding and technical assistance for states to identify and evaluate environmental health threats to communities, as well as educate the communities about health risk or other findings.

At the local level, public health laboratories provide diagnostic testing, disease surveillance, applied research, laboratory training and other essential services to the communities they serve. Laboratory work is diverse, yet accomplished by highly trained and skilled professionals.

Public health laboratory professionals and epidemiologists are the ones working behind the scenes on the issues that you hear about in the news. These include: newborn screening; Lyme disease; West Nile virus; food borne illness outbreak investigations; and bio-terrorism threats. The Association of Public Health Laboratories was founded by state and territorial public health laboratory directors serving communities across the United States. You may want to visit this website to learn more about the public health laboratory expertise and services available in your own community.

Essential Service #3: Communicate effectively to inform and educate.

You have probably come across—and even participated in— health promotion and social marketing efforts in your community.

Essential Service #3 encompasses public health activities such as:

- Social marketing and targeted media public communication (e.g., Toll-free information lines);

- Providing accessible health information resources at community levels (e.g., free, mobile health screening initiatives);

- Active collaboration with personal health care providers to reinforce health promotion messages and programs; and

- Joint health education programs with schools, churches, and worksites (e.g., stress reduction seminars; parenting support groups for enhancing mental health; and health fairs).

You may have noticed national media campaign advertisements on television, billboards, or even posters or fliers in your doctor’s office. Some examples include the “Back to Sleep” campaign to prevent Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, or the anti-substance use campaign, “Just Say No.”

Many national awareness weeks also relate directly to public health efforts. The American Public Health Association, headquartered in Washington, D.C., actually sponsors a “National Public Health Week” each spring. You can find additional information, and links to free tools and resources for National Public Health Week. You may decide to sponsor an event such as a fun run or health fair to raise public health awareness in your own community!

Essential Service #4: Strengthen, support, and mobilize communities and partnerships.

These activities represent a comprehensive approach to community health, in which professionals and even entire sectors of a community collaborate to plan, implement, monitor, evaluate, and subsequently modify activities, and repeat the process as needed.

Essential Service #4 encompasses public health activities such as:

- Convening and facilitating community groups and associations, including those not typically considered to be health-related, to undertake defined preventive, screening, rehabilitation, and support programs; and

- Skilled coalition-building ability in order to draw upon the full range of potential human and material resources in the cause of community health.

This is not unlike the PATCH logic model – the Planned Approach to Community Health

Included in the PATCH strategy are five elements that are fundamental to the success of any community health promotion process:

- Community members participate in the process.

- Data guide the development of programs.

- Participants develop a comprehensive health promotion strategy.

- Evaluation emphasizes feedback and program improvement.

- The community capacity for health promotion is increased.

You can read about a similar process for mobilizing community partnerships to identify and solve health problems in the Community Tool Box’s Community Action Guide: A Framework for Addressing Community Goals and Problems.

The overall goal of action planning is to increase your community’s ability to work together to affect conditions and outcomes that matter to its residents—and to do so both over time and across issues of interest.

As your community works towards a broad vision of health for all, creating supportive conditions for change requires comprehensive efforts among diverse sectors of the community. These include health organizations, faith communities, schools, and businesses. Representatives of each sector come together to form a community coalition. Your community coalition can strive to influence systems changes—programs, policies, and practices that can enhance or detract from the community’s capacity to be a supportive environment for healthy living.

Essential Service #5: Create, champion, and implement policies, plans, and laws.

Because state and local public health programs are often funded at least in part with Federal dollars, accountability is often a key issue. Public health programs therefore document progress towards positive change in health behavior or health status indicators. For example, the Federal Maternal and Child Health Services Block Grant, which imposes a $3 state match for every $4, requires annual reporting of “performance measures.” Some of those are state-negotiated to allow for flexibility in tracking health behavior or health status indicators that are unique to a state’s populations. Data such as these can be presented to policymakers to document the value or effectiveness of a program. Those data can also be used for continued program planning and modification.

Essential Service #5 encompasses public health activities such as:

- Leadership development at all levels of public health;

- Systematic community-level and state-level planning for health improvement in all jurisdictions;

- Development and tracking of measurable health objectives as a part of continuous quality improvement strategies;

- Joint evaluation with the medical health care system to define consistent policy regarding prevention and treatment services; and

- Development of codes, regulations, and legislation to guide the practice of public health.

Active Living by Design is a national program of The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and is a part of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Public Health. The program establishes and evaluates innovative approaches to increase physical activity through community design, public policies, and communications strategies. The program funds community partnerships to develop, implement and sustain collaboration among a variety of organizations in public health and other disciplines, such as city planning, transportation, architecture, recreation, crime prevention, traffic safety and education, and key advocacy groups. Collaborators focus on land use, public transit, non-motorized travel, public spaces, parks, trails, and architectural practices that advance physical activity.

One example of an Active Living by Design initiative is: “Obesity and The Built Environment: Improving Public Health through Community Design.” You can learn more about this and other initiatives by visiting Active Living by Design.

Essential Service #6: Utilize legal and regulatory actions.

While you may not always be conscious of how public health regulations have influenced your community environment, think about some of the things that you see or experience when you visit restaurants. You may have noticed a framed certificate hanging on the wall, with “Sanitation Grade A.” This certificate is a result of local health department inspections to assure that the restaurant is in compliance with food storage, handling, and preparation regulations.

While at that same restaurant, you may also notice a sign that says, “No smoking.” This may be a direct result of a statewide law that was designed to improve the environmental health conditions in your community.

If you have school-aged children and have had to prepare them for entrance into the public school system, you know that the full series of immunizations is required. Immunizations are required for school-aged children in the United States because when widespread immunizations are in place, we all benefit from what is referred to as “herd immunity.” When a group of people (e.g., an entire community, state, or nation) is immunized against an infectious disease, it makes it more difficult for the disease to spread and cause an epidemic.

Essential Service #6 encompasses public health activities such as:

- Full enforcement of sanitary codes, especially in the food industry;

- Full protection of drinking water supplies;

- Enforcement of clean air standards;

- Timely follow-up of hazards, preventable injuries, and exposure-related diseases identified in occupational and community settings;

- Monitoring quality of medical services (e.g., laboratory, nursing homes, and home health care); and

- Timely review of new drug, biologic, and medical device application.

Essential Service #6 may be implemented in your community as a result of either state or federal legislation. Not only can you take on a leadership role in your community to assure that public health regulations are enforced; you can be a catalyst for change by identifying and prioritizing new issues, and sponsoring new regulations through public health advocacy.

Essential Service #7: Enable equitable access.

Essential Service #7 encompasses public health activities such as:

- Assuring effective entry for socially disadvantaged people into a coordinated system of clinical care;

- Culturally and linguistically appropriate materials and staff to assure linkage to services for special population groups;

- Ongoing “care management;”

- Transportation services;

- Targeted health information to high risk population groups; and

- Technical assistance for effective worksite health promotion/disease prevention programs.

The implementation of this Essential Service is inherently linked to the social, economic, and political climate in communities, states, and the nation. To assure the provision of health care when it is otherwise unavailable, the United States federal government funds two “safety net” programs: Medicaid and the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP).

Medicaid is the largest source of funding for medical and health-related services for people and families with low incomes and resources. This program became law in 1965, and is jointly funded by the federal and state governments (including the District of Columbia and the Territories) to assist states in providing medical long-term care assistance to people who meet certain eligibility criteria.

The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 created a new children’s health insurance program called the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP). SCHIP is a state administered program, and each state sets its own guidelines regarding eligibility and services for children up to age 19 who are uninsured. Families who earn too much to qualify for Medicaid may still be able to qualify for SCHIP.

To learn more about the Medicaid and SCHIP programs and how they can benefit members of your community, please visit: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.