51 Southeast Asia: Overview

Physical Geography

Landforms

Mainland Southeast consists of two major peninsulas. The broad Indochina Peninsula extends from the South China Sea to the Bay of Bengal. The narrower Malay Peninsular extends southward from Indochina, terminating at the island of Singapore. Much of the northern part of Indochina is mountainous, the result of India’s tectonic collision with Asia. The “wrinkling” of the fabric of Asia radiates southward through Indochina, with most of the major ridges and valleys running north-to-south. Many of the valleys contain a major river, and the cultures of the regions largely coalesced around those rivers – the Irrawaddy and Salween in Myanmar; the Chao Praya in Thailand, the Mekong in Laos, Cambodia, and southern Vietnam, and the Red in northern Vietnam. Southern Indochina and the Malay peninsula features some hilly landscapes, but the elevations are generally lower in the south, and the highlands are separated by broad plains.

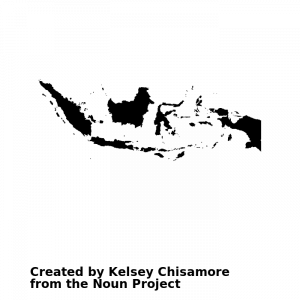

The Southeast Asian archipelago – occupied primarily by Indonesia and the Philippines – is made up of thousands of islands that were created by the collision of the Indo-Australian and Philippine tectonic plates. Hilly to mountainous landscapes dominate many of these islands, and the area is susceptible to deadly seismic and volcanic activity. Over the last two decades, more than 100,000 Indonesians have been killed by earthquakes, volcanoes, and tsunamis.

Climate

The temperature patterns of Southeast East are relatively simple. The vast majority of the region lies in the tropics, and is therefore warm to hot year-round. Colder conditions can be found in highlands areas, with temperatures dropping about 1°F for every 300 feet of elevation gained, and winters in northern Vietnam and Laos can be relatively cool. Still, only in the loftiest elevations of northern Indochina do air temperatures approach anything that could reasonably be called “cold.”

Greater variations can be found in precipitation patterns. Indonesia, the Malay peninsula, and the southern Philippines are generally wet year-round, due to the close proximity of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). Exceptions can be found during El Niño seasons. An irregular climate regime that occurs, on average, every two to seven years, and that can last for several months, El Niño is associated with severe storms on the Pacific side of the Americas. In Southeast Asia, however, El Niño is associated with severe droughts. During severe El Niño seasons, equatorial Southeast Asia often suffers crop failures and major forest fires.

The Southeast Asian mainland experiences a distinct monsoon precipitation cycle (see Chapter 70), with a dry season lasting from approximately November through April, and a rainy season lasting from May through October. Generally, the wettest parts of the Indochina peninsula are found near the coasts, and the driest areas in the interior.

Historical Geography

Nearly every country in Southeast Asia was once colonized by a European empire. In many other areas that were colonized by the Europe, the political boundaries set by the imperial powers were completely arbitrary – having no relationship to preexisting cultural patterns – and resulted in the creation of inherently unstable multi-national states. (This is especially true of Sub-Saharan Africa and Southwest Asia.) While it is not entirely untrue in Southeast Asia, the current political map of the region does bear some resemblance to pre-colonial political patterns. That is, most of Southeast Asia’s current countries existed in some similar form prior to colonization.

The first Cambodian (Khmer) state dates back to the 800s CE, when the Khmer Kingdom assumed control of much of Indochina. The kingdom entered a state of severe decline during the Black Plague of the 1300s, and subsequently lost much its territory to the Thai and Vietnamese. In the 900s, Vietnam gained independence after nearly a millennium of Chinese rule, and in the 1400s, the Vietnamese expanded southward to the Mekong River delta, displacing the Khmer. Burmese Buddhists began to forge a kingdom in the Irrawaddy Valley in the 1000s. The kingdom was topped by Mongol invaders in the 1200s, but was reunified in the 1500s. (Long known as Burma, the country adopted the name Myanmar in the 1989.) The Thai began to migrate south along the Chao Praya river from southern China in the 500s, and established a Thai kingdom there (known as Siam) in the 1200s. Laos first unified as a kingdom in the 1300s, but fell under the control of Siam in the 1700s. From the 1300s to the 1500s, a kingdom based in eastern Java established control over much of modern-day Indonesia. Malaysia originated in the 1400s as the state of Malacca, governed by a Muslim prince, which would serve as an independent trading hub for Malay, Chinese, Arab, Indian, and European merchants for about a century. Only the Philippines was never dominated by a single major civilization. Prior to colonization, the Philippine Islands were a collection of small, independent countries, the most significant ones organized around seaport city-states.

The European colonization of Southeast Asia began in the 1500s. Portugal assumed control over Malacca and East Timor (Timor-Leste), and Spain began to colonized the islands that would ultimately make up the Philippines (named for the Spanish King Philip II). In the 1600s, the Dutch began to slowly establish control over Indonesia – named the Dutch East Indies – which would ultimately become one of the world’s most lucrative colonies.

Britain, France, and the United States would establish colonies in Southeast Asia in the 1800s. The British forced the Portuguese from Malacca, and established a major naval base on the island of Singapore. Located on a strategic sea-lane linking China and India, Singapore would ultimately become one of the world’s busiest ports, and Southeast Asia’s most important financial center. The British then extended their control over the rest of the territory that constitutes modern-day Malaysia, made Brunei a British protectorate, and annexed Burma (Myanmar) into British India. France annexed Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, forming a colony known as French Indochina. The United States, having defeated Spain in a war, assumed control of the Philippines in 1898. Siam (Thailand) fell into the British trading sphere, and lost significant territories in Laos and Cambodia to the French, but was never formally colonized. Thailand has the distinction of being the only Southeast Asian nation to avoid colonization.

Independence for Southeast Asia was precipitated by World War II. Nearly the entire region was colonized by Japan, and armed resistance forces were organized throughout much of Southeast Asia. After Japan’s defeat, the European and American colonizers, themselves weary of war, returned to face experienced resistance fighters, and were eventually forced to grant their colonies independence. The Philippines and Burma gained independence in the 1940s, followed by Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos in the 1950s.

Only Brunei and Timor-Leste would remain as European colonies well into the second half of the twentieth century. Brunei remained a British protectorate until 1984. Timor-Leste would gain independence from Portugal in 1974, but would be invaded by Indonesia shortly thereafter (see Chapter 49).

Singapore remained a British colony until 1963, when control of the city was handed to Malaysia. Singapore would soon separate from Malaysia, becoming an independent city-state in 1965. There were multiple reasons for this. First, Indonesia had always objected Malaysian independence, believing that its territory should be incorporated into their country. They were especially troubled that Singapore, which was very important to the Indonesian economy, should be controlled by Malaysia. Granting Singapore independence brought some satisfaction to Indonesia, and improved its relationship with Malaysia. There were also a cultural reason. Singapore’s large Chinese and Indian populations threatened to make Malays a minority in their own country, and granting Singapore independence allowed Malays to be the majority. Finally, Singapore was more than happy to control its own political and economic destiny.

Much of the second half of Southeast Asia’s 20th century was defined by the ethnic conflicts and by Cold War politics, which are discussed in Chapters 40 and 42.

Cultural Geography

Religion

Buddhism is the dominant faith in most of mainland Southeast Asia, including Cambodia (95% Buddhist), Thailand (94%), Myanmar (88%), Singapore (74%), Laos (65%), and Vietnam (50%). Muslims form the majority in Malaysia (60% Muslim) and Indonesia (86%). Indonesia is, in fact, the world’s largest Muslim country. Christianity is the dominant faith in Timor-Leste (97% Christian) and the Philippines (91%). Both countries are overwhelmingly Roman Catholic, a legacy of Portuguese and Spanish colonization.

Ethnicity and Language

Southeast Asia is an incredibly complex cultural region. Many of the countries could be considered nation-states, but nearly all of them contain a significant number of ethnic minorities. The table below shows some of the larger ethnolinguistic groups in each country.

| Country | Largest Ethnolinguistic Groups |

|---|---|

| Thailand | Thai (96%) |

| Cambodia | Khmer (90%); Kinh (5%) |

| Vietnam | Kinh (86%) |

| Singapore | Chinese (74%); Malay (13%); Indian (9%) |

| Myanmar | Burmese (68%); Shan (9%); Karen (7%); Chinese (3%) |

| Brunei | Malay (66%); Chinese (10%) |

| Laos | Lao (55%); Khmu (11%); Hmong (8%) |

| Malaysia | Malay (50%); Chinese (23%); Indian (7%) |

| Indonesia | Javanese (40%); Sundanese (16%) |

| Timor-Leste | Tetun (37%); Mambai (17%); Makasai (11%); Baikenu (6%) |

| Philippines | Tagalog (28%); Cebuano (13%); Ilocano (9%); Bisaya (8%); Hiligayon (8%); Bikol (6%) |

Remarkably, the ethnic composition of Southeast Asia is even more complex than this table suggests. The Philippines, for example, is home to 182 different ethnic groups. The region’s ethnic complexity is partly the result of its physical geography. Its thousands of islands and isolated mountain valleys led to the evolution of many distinctly different cultures. At the same time, the region as a whole is highly accessible, surrounded by oceans on of the world’s busiest trade routes. This has resulted in numerous outside groups contributing their own cultural traits and enhancing the cultural diversity of the region.

The region’s cultural complexity lends itself to the political risk of ethnic separatism, which is discussed in Chapter 40.

Population Geography

Population Distribution

Indonesia is the population giant of Southeast Asia. Home 261 million people, it is the fourth-largest country in the world. Other populous countries include the Philippines (103 million), Vietnam (93 million), Thailand (68 million), Myanmar (54 million), and Malaysia (32 million). The remaining countries have considerably smaller populations, including Cambodia (16 million), Laos (6 million), Timor-Leste (1 million), and Brunei (400,000).

Like all regions, Southeast Asia’s population distribution is very uneven. The interior areas of many of the region’s islands are sparsely populated. The heavy rainfall in the region tends to leach nutrients out of the soil, making them largely unsuitable for permanent agriculture and, therefore, incapable of sustaining large populations. The highland areas of Southeast Asia’s mainland also tend to be lightly populated. Farming in mountainous terrain is difficult, and the rugged topography also limits transportation opportunities, which in turn limits economic opportunities.

Southeast Asia’s islands tend to be most densely populated along the coasts, where the flat landscapes and rich alluvial soils allow for more productive agriculture. Coastlines also provide opportunities for fishing and trade, further increasing economic possibilities. On the mainland, population densities are highest along major rivers, which provide fertile soils for agriculture, as well as opportunities for fishing and trade.

One of the region’s most densely populated places is the Indonesia island of Java, which is about the same size as Illinois. But while Illinois is home to 13 million people, Java is home to 143 million. The island has been densely populated for centuries due its rich volcanic soils.

Only three of Southeast Asia’s countries are home to a majority urban population: Singapore (100% urban), Brunei (76%), and Malaysia (72%). The rest of the region’s countries are still mostly rural, including the Philippines (49% urban), Indonesia (44%), Thailand (34%), Myanmar (34%), Laos (33%), Vietnam (30%), Timor-Leste (28%), and Cambodia (20%). But even in the most rural countries, the population of Southeast Asia is urbanizing rapidly. With the notable exception of Singapore, many of the region’s major cities are facing immense challenges associated with rapid growth, including housing shortages and severe pollution. Many recent arrivals to these cities, unable to afford formal housing, are forced to live in makeshift squatter settlements, often without basic services like water and electricity.

Population Growth

Southeast Asia is a perfect illustration of the demographic transition. For centuries, the region was sparsely populated, its slow population growth the result of extremely high death rates. Death rates plummeted when modern technology was introduced, and the mostly rural region’s high birth rates caused population to explode upward. In 1800, Southeast Asia was home to just 10 million people. By the 1970s, the population was over 300 million, and was well over half a billion by the end of the twentieth century. As time marched on, the countries of Southeast Asia moved toward the latter stages of the demographic transition. In the 1960s, the region’s total fertility rate (TFR) was 6.1. By the 2000s, it had dropped to 2.2.

There is still a broad regional variation in TFRs. Five countries have TFRs above the global average of 2.4, including Timor-Leste (5.3), the Philippines (3.2), Laos (3.0), Cambodia (2.8), and Malaysia (2.6). Two countries are below the world average, but still above the replacement rate of 2.1, including Indonesia and Myanmar, each with TFRs of 2.2. Four countries are now below replacement rate, including Vietnam (1.9), Brunei (1.9), Thailand (1.7), and Singapore (0.8). There are many reasons for these variations but, in general, countries with higher TFRs tend to be more rural, poorer, less educated, and more religiously conservative. Countries with lower TFRs tend to be more urban, wealthier, better educated, and more religiously moderate.

Political Geography

Five of Southeast Asia’s are free democracies, albeit imperfect ones. Malaysia has been a constitutional monarchy since independence, and although it has recently experienced numerous high-profile corruption scandals, its citizens have long enjoyed free, multi-party elections. The Philippines has been a democracy since 1986, when longtime dictator Ferdinand Marcos was forced from power. The country has held free elections since then, but is still somewhat unstable, suffering through corruption, mass demonstrations, and threatened coups. The recent president, Rodrigo Duterte, has been accused of ordering more than 7,000 extrajudicial killings. In 2022, Ferdinand Marcos’s son, Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos, Jr. was elected president, further fueling concerns of a drift toward authoritarianism. Indonesia held its first free elections in 1999, but the current century has been marred by ethnic separatism, a lack of strong leadership, and corruption. Timor-Leste has had stable and fair elections since 2007, but the government there faces monumental challenges in the region’s poorest country. Singapore is perhaps the region’s most stable country. It has been a democratic republic since independence. It has been largely governed by one political party for decades, but is a peaceful, if somewhat obsessively orderly, state.

Two of Southeast Asia’s countries, Thailand and Cambodia, are partial democracies. Thailand has officially been a constitutional monarchy since 1932, but it was effectively ruled by the military until 1992. In the 1990s, a more open, multi-party democracy emerged, and several free elections were held. However, in both 2006 and 2014, the military overthrew democratically elected governments. There have been free elections since the last coup, but Thailand’s government continues to live under the shadow of the military, and it appears that its democratic institutions may be headed in the wrong direction. Even during its long periods of military rule, most of Thailand’s citizens enjoyed basic freedoms. In recent years, however, the government has arrested numerous critics, including students, professors, and journalists, and many of them died in custody. The government has also re-routed all of the country’s internet activity through government servers in order to monitor it for dissent.

Cambodia was been a constitutional monarchy since 1993, when its first free elections were held. Hun Sen, a former Khmer Rouge fighter, was elected prime minister, and has led the country ever since. Subsequent elections are widely believed to have been fraudulent. Hun Sen’s regime has been occasionally tolerant of political dissent, and Cambodians enjoy moderate amount of personal freedom. Still, the imprisonment of political dissidents has been common any time Hun Sen’s regime appears to be under genuine threat.

Four of Southeast Asia’s countries are non-democracies. Vietnam and Laos are still ruled by their respective communist parties. Human rights violations remain commonplace, but are less frequent today than in past decades. Brunei is a sultanate and former British protectorate that gained full sovereignty in 1984. It has been ruled internally by the same family for six centuries.

Cartography by Steve Wiertz.

In 1962, the democratically elected government of Burma was ousted in a military coup. For the next three decades, the military developed a highly isolated, repressive, and xenophobic police state. By 1990, the country, now renamed Myanmar, was facing significant international sanctions due to its poor human rights record. The military agreed to hold free elections, and opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi led her anti-military party to a landslide victory. The military quickly nullified those election results and placed Suu Kyi under house arrest, triggering another round of international sanctions. In the 2000s, Suu Kyi was released from house arrest, and she formed a new opposition party, the National League for Democracy (NLD). Her rallies attracted huge crowds, and the military once again placed her house arrest. She was released again in 2010 and, two years later, Myanmar again held elections. The NLD won 43 of the 44 open parliamentary seats. In 2015, a new round of elections gave the NLD 60% of the seats in parliament. It was lauded as success story for democracy, and the foreign community continued to ease its sanctions. Unfortunately, the military staged another coup in 2021 and declared martial law. Many NLD leaders were arrested, sparking mass protests that were met with lethal responses from the military.

Economic Geography

Agriculture was long the dominant economic activity in Southeast Asia, and continues to employ about 60% of the population. Traditionally, most of the rural population have been small-scale farmers growing rice as a subsistence crop and tobacco, coffee, or rubber as cash crops. Agriculture’s importance to the region’s economy has long been in decline, today accounting for only about 15% of the region’s GDP. Mining and manufacturing have begun to dominate the export economy, and smaller farms are increasingly being combined into larger corporate farms.

Large-scale industrialization arrived in Southeast Asia in the 1960s, particularly in Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Singapore. Initially, the region’s factories primarily produced cheap consumer goods such as clothing, shoes, and toys. In the 1970s, free trade agreements led to a significant expansion of the region’s manufacturing. Transnational corporations were attracted by the region’s abundant raw materials, low taxes, inexpensive but relatively well-educated labor, and lax environmental and labor laws. In recent decades, the region’s manufacturing has grown more sophisticated, supplying the world with cars, chemicals, appliances, and electronics.

By the 1980s and 1990s, the world was incredibly optimistic about Southeast Asia’s economic prospects. A little too optimistic, as it turned out, and the region suffered a massive economic collapse in 1997. (See Chapter 41).

Singapore, Malaysia, and Brunei are the region’s wealthiest countries, and enjoy standards of living that are above the world average. Singapore has served as the region’s financial and transportation center for over a century, and is one of the richest places on earth. Malaysia has long been one of Asia’s wealthier countries due to its natural resources, and it has been Southeast Asia’s most productive manufacturer since the 1970s. Brunei’s economy is not terribly complicated, but it does have an abundance of oil and a small population, and therefore one of the region’s highest per capita incomes.

Photo by Arthur Fedde.

Thailand, the Philippines, and Indonesia are Southeast Asia’s middle-income countries, featuring overall standards of living that are close to the world average. For years, the economies of these countries were based on the export of agricultural products and other natural resources. All three industrialized in the second half of the twentieth century, lifting millions out of poverty. Still, the economic growth of these countries has been stunted by falling commodities prices, political instability, and government corruption.

Southeast Asia’s poorest countries are Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Timor-Leste, and Myanmar. Effective social welfare programs have kept Vietnam’s standard of living close to the world average, but Cambodia, Laos, Timor-Leste, and Myanmar’s overall standards of living are well below the world average. They are among the poorest countries in Asia.

Newly independent Timor-Leste is the poorest country in the region, and is still largely dependent on foreign humanitarian aid. Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos were impoverished by decades of Cold War conflicts and inefficient communist economic policies. Inspired by China, all three have introduced market reforms and lured foreign investment. They have experienced modest growth driven by low-wage manufacturing and tourism. Still, their rigidly authoritarian governments are likely to inhibit significant economic growth for the foreseeable future. Myanmar, with its abundant natural resources and relatively well-educated population, has tremendous economic potential, but that potential has been destroyed by decades of corruption, conflict, and international sanctions.

Did you know?

Cited and additional bibliography:

Fedde, Arthur. Meal in Bangkok. Photo.

Keith.Fulton. Singapore. July 16, 2017. Photo. https://www.flickr.com/photos/fultons/35910056116/. Attribution-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-ND 2.0).

Wiertz, Steve. Myanmar. College of DuPage GIS class, May 2022.