83 Central Asia: Historical Geography I – Fixing the Aral Sea

“The small Aral is not a real sea.

The old one used to have waves seven meters high.”

Sagnai Zhurimbetov, who fished on the Aral Sea over 56 years

A Turkestani proverb says – The moon cannot be covered by a skirt. In application here, indeed there was no way to hide the disaster of the Aral Sea.

Under Mikhail Gorbachev’s policy of гласность (glasnost’) or openness, even in the Soviet Union the ecological demise of the Aral Sea gained attention. During Gorbachev’s rule, he canceled consideration of a massive plan to divert Siberian rivers to the Aral Sea. While theoretically this project could have refilled the sea, it would have cost billions of rubles and itself caused untold ecological damage. Wisely, the project was canceled. But wait! In the early 2000s, interest in the project was renewed, supported by Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. But, no.

No rivers have been diverted, but what has been done? The biggest step toward fixing the Aral Sea was the construction of the Kokaral Dam. This dam severed the North Aral Sea from the South Aral Sea. However, while this step has been successful for the North Aral Sea, it meant the abandonment of the rest of the once watered area.

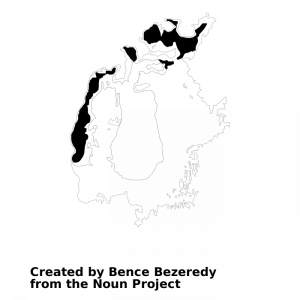

Over the years of Soviet cotton irrigation in Central Asia, the Aral Sea declined in volume, surface area, and depth. Eventually, the decline was so sufficiently major that the waters separated into different basins, based on the bathymetry of the Aral Sea. That is, shallow areas were revealed while deeper areas retained water. Naturally, ridges between deeper waters separated those waters. One of these major ridges split the sea into two – the North Aral Sea and the South Aral Sea. Later the southern sea parted into western and eastern lobes, while other smaller pockets broke off. The eastern lobe of the southern sea fluctuates between a modest shallow ponds and since 2015 a dry barren desert space.

As the North Aral Sea received larger volumes and more consistent flows of water than the South Aral Sea did, sometimes water would flow from the north to the south bodies. While the southern waters are split between Kazakh and Uzbek jurisdictions, the northern waters splash entirely within Kazakhstan. Seeking to preserve its North Aral Sea, Kazakhstan built the Kokaral Dam to permanently separate north from south, doing so entirely on Kazakh territory. Given that the Amu Darya continues to contribute trickles to the South Aral Sea, the northern dam has condemned to southern waters to maintain the status quo. In contrast, the Syr Darya delivers more consistent and somewhat larger volumes of water to the North Aral Sea, where the dam allows the water levels to increase. Dam work had early problems, but by 2005 a secure barrier was established.

The North Aral Sea now is a success story. Within a few months of the dam’s completion, water levels had risen to ten feet, even though scientists had expected this to take ten years. In fact, by now the waters have risen so high that some water slips over the dam to be wasted in the southern basin. Fishing has been restored, using reintroduced fish stocks. Waters are not back to their original levels, but Kazakhs are enthusiastic about the recovery so far.

The notion of stopping the vast irrigation of cotton is a non-starter. Uzbekistan is the fifth largest exporter of cotton in the world. The money is too much to give up. Thus, the South Aral Sea continues to dwindle, probably toward complete elimination of water and continuation of hazards. Without the water, salt and sand cover the area, but can blow for miles with strong winds. Salt storms and sand storms can blow over the distant downs and ironically over cotton fields. The salt and sand can be damaging to people and to cotton. These storms even reach Turkmenistan where over half of children’s health problems are respiratory. In Geography, this situation is called a negative externality – a circumstance where a problem from across the border hurts you, but you have no jurisdiction or authority to address the problem.

Vozrozhdeniya Island was an actual island in the pre-Soviet Aral Sea. The Soviet military decided that such an isolated location would be a useful site for bioweapons research, starting in 1948 with a center named Aralsk-7. With the shrinkage of the Aral Sea, in 2001 Vozrozhdeniya Island attached itself to the mainland, thus becoming a peninsula. At that point in time, the Soviet Union had dissolved, but remnants of bioweapons research remained on the island, but now theoretically accessible by land. With American assistance, Uzbekistan decontaiminated ten anthrax burial sites in 2002.

The Aral Sea has recovered in part. Only the Northern Aral Sea has partly regained its previous levels of water and fish, while the Southern Aral Sea continues its exorable path to vanish completely.

Did you know?

The idea of diverting Siberian rivers to Central Asia was not new to the Gorbachev era. As early as 1830, the notion was discussed. Considering that Siberian rivers flow northward to the Arctic Ocean, there was some argument that the waters of these rivers were “wasted.” In the 1960s, tentative plans for this type of project included use of small nuclear bombs to blast the many miles of canals needed for the construction. It never happened.

Iran’s saline Lake Urmia also have suffered from catastrophic declines in water levels. Around the world, other large lakes are suffering from significant loss of water – in the United States, Lake Mead, for instance.

In 1971, an accidental release of the smallpox virus from Aralsk-7 killed three people and prompted emergency vaccinations.

Cited and additional bibliography:

Blood, de:User:Kapitän Nemo; de:User:Captain. English: One of the Versions (Probably, 1960s Vintage) of the Russian Northern Rivers Diversion Plan. The Scheme Depicted Involves Transfer of Water from the Yenisei into the Ob, and Piping Water Upstream from the Ob via Irtysh and Ishim, and Then a Canal, toward the Aral Sea. An Actual Implementation Would Also See a Canal Skirting the Aral Sea from the East (Not Shown on This Map), to Bring Water to the Syr Darya and Amu Darya. Russia. 14 Apr. 2007. File:Russland top.png, Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Russland_Dawydow.PNG. Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported(CC BY-SA 3.0).

Chen, Dene-Hern. The Country That Brought a Sea Back to Life. BBC. 23 July 2018. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20180719-how-kazakhstan-brought-the-aral-sea-back-to-life.

Nasar, Rusi. “HOW THE SOVIETS MURDERED A SEA.” Washington Post, 4 June 1989. www.washingtonpost.com, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/opinions/1989/06/04/how-the-soviets-murdered-a-sea/b4a1b9d7-44c7-4d09-9885-ddd29d1a447c/.