62 East Asia: Physical Geography II – Karst

What is karst? Most people have never heard of karst. Perhaps it seems like a misspelling of some other word. In fact, it is a type of landscape that can be found in different parts of the world. As highlighted in the icon to the left, caves are possible features of karst landscapes. In this chapter on East Asia, we note that China has a number of locations featuring a karst landscape; in fact, one area is famous and distinctive enough to be a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Karst is created from the interaction of water and limestone. Consider a rainy day. Rain falls from clouds and strikes the Earth’s surface. There are many possible surfaces that may become wet. In populated areas, rain may fall on a manmade surface, for instance on a paved surface. In that case, water may run off, reaching soil, lawns, or drains. Water may pool on a hard surface and progressively evaporate. Also, urban areas may have ponds, rivers, or lakes where the rainwater hits.

Photo by Alex Berger on Flickr.

In rural areas, rainwater may land on a rocky surface, analogous to manmade pavements. Most likely though, the rain will fall onto soil or vegetation. Of course, rural areas outside of deserts will feature ponds, rivers, and lakes in which rain may land.

So, rainwater may stay directly in the hydrologic cycle by landing in water. The hydrologic cycle follows the path of precipitation from its downward flight to its return to the atmosphere in evaporation. Rain to lake to surface evaporation to clouds to rain again is a simple process. Rain that reaches a hard surface and runs into a body of water has a similarly straightforward path in the hydrologic cycle. What about rain that reaches the soil or vegetation? Of course, some of that water will be utilized by the vegetation to sustain itself and further plant growth.

However, some of the rainwater may move freely through the soil. The ability of water to move through the soil does vary by the type of soil. Clay is relatively impermeable, inhibiting the flow of water. In contrast, sand is highly permeable, allowing water to move easily.

So, let’s take a somewhat permeable soil that receives a good rainfall. That water moves through the quite small air pockets in the soil. As the water moves, it interacts with the air, in part causing a chemical reaction that creates carbonic acid – carbon dioxide and water mixed.

| H2O | + | CO2 | → | H2CO3 |

Next, this carbonic acid percolates through the soil. In most cases, this carbonic acid, as a mild acid, is harmless. However, carbonic acid reacts chemically with limestone (and dolomite). With these rock strata, carbonic acid very slowly dissolves the limestone. Over many, many years the limestone may be completely dissolved. As a result, there are gaps of varying sizes in the soil and rock, somewhere below the ground’s surface. Consequently, caves may be formed. Or, the surface may collapse into the open space, creating a sinkhole. Given that limestone represents about ten percent of the Earth’s sedimentary rock, there are numerous sites of limestone across the planet.

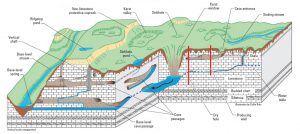

Alternatively, limestone may be present on the surface, uncovered by soil. This limestone may be dissolved and eroded away. In this case the limestone areas will disappear, while adjacent non-limestone landforms will remain. Over lengthy periods of time, these other rock formations will appear as towers amidst lower lands that once held limestone. Indeed, there are a number of different karst landforms created from varied settings of limestone dissolution. Note this illustration.

Photo by Rod Waddington on Flickr.

In our chapter today, we note that China, particularly south and southeast China, has extensive karst landscapes. These lands, covering half a million square kilometers (about 500,000 km2) are so widespread and visually striking that this region has been designated at a UNESCO World Heritage site. Across the provinces of Chongqing, Guangxi, Guizhou, and Yunnan, there are diverse types of karst landscapes, including the stone forests, caves, and tower, pinnacle and cone karst. The stone forests of Shilin are well-known; in fact, “Shilin” 石林 means “stone forest” in Mandarin. Fine examples can be seen in Naigu Stone Forest and Suyishan Stone Forest near the city of Kunming. The Li River (seen to the left) is a popular waterway for tourists to view the cones and hills of the adjacent karst.

Did you know?

Karst is present in the United States as well. Nearly all of the states of Florida and Missouri have karst landscapes, as well southwestern Texas, eastern Iowa, eastern Indiana, western Ohio, central Kentucky, and much of Tennessee. Florida, in particular, is known for sinkholes.

Additional and cited bibliography:

Berger, Alex. Zhangjiajie National Park. February 2, 2018. Photo. https://www.flickr.com/photos/virtualwayfarer/27759205508/. Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. “South China Karst.” UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Accessed September 11, 2021. https://whc.unesco/org/en/list/1248/.

“File:KarstterrainUSGS.Jpg – Wikimedia Commons.” Public Domain. Accessed September 11, 2021. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:KarstterrainUSGS.jpg. Figure 1 in Taylor, Charles J., and Earl A. Greene. “Hydrogeologic characterization and methods used in the investigation of karst hydrology.” US Geological Survey (2008). Chapter 3 of Field Techniques for Estimating Water Fluxes Between Surface Water and Ground Water, Edited by Donald O. Rosenberry and James W. LaBaugh, Techniques and Methods 4–D2. Available from USGS at https://pubs.usgs.gov/tm/04d02/pdf/TM4-D2-chap3.pdf.

Waddington, Rod. Li River. May 21, 2019. Photo. https://www.flickr.com/photos/rod_waddington/47898625751/. Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.0).