25 NAME: Overview

Physical Geography

Climates

North Africa and the Middle East is an exceptionally dry place. Much of the region is covered by deserts – areas that receive less than ten inches of rainfall per year, where vegetation is either scarce or absent, and where daytime temperatures are the hottest ever recorded on earth. Much of the region’s aridity is caused by the presence of sub-tropical highs, including one over the Sahara, the world’s largest desert. In many places, deserts are created or enhanced by the rain shadow effect. Outside of the Sahara, which dominates most of North Africa, desert climates can be found in southern Israel, most of Jordan, western Iraq, central Iran, and nearly all of the Arabian Peninsula. Most of the rest of the region is dominated by a steppe climate – semi-arid regions characterized by grasslands and scrub vegetation – including the Atlas Mountains of northwestern Africa, the highlands of the southwestern Arabian Peninsula, the interior of Turkey, eastern Iraq, and much of Iran. The region’s wettest areas possess a Mediterranean climate, featuring dry summers and wet winters caused by the seasonal oscillation of sub-tropical highs and the westerlies. Places with a Mediterranean climate include the northern coasts of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia, far northeastern Libya, northern Israel, Lebanon and Syria, northern, southern, and western Turkey, and northwestern Iran.

Landforms

Photo by Jennifer Birkhofer.

Much of North Africa and the Middle East consists of relatively flat landscapes, including most of the Sahara, the inland areas of the Arabian Peninsula, the coastal plains of the Persian Gulf, and the Syrian and Iraqi deserts. Highland areas are found along both shores of the Red Sea and in and around the country of Lebanon. The most mountainous areas are found in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia, the Pontic and Taurus Mountains of Turkey, and he Elburz and Zagros Mountains of Iran.

Historical Geography

North Africa and the Middle East is the birthplace of human civilization. The world’s first agricultural societies emerged 10,000 years ago in the upper reaches of the Tigris and Euphrates River valleys. The evolution of agriculture gradually allowed some people to separate from the task of food production and develop specialized occupations, such as merchants, artisans, clerics, soldiers, and engineers. These people gathered together in the world’s earliest cities, and from these cities the world’s first civilizations were born. For thousands of years, some of the world’s most substantial empires emerged in the region, including the Sumerian Empire (4500s – 1900s BCE), the Egyptian Empire (3100s – 300s BCE), the Babylonian Empire (1900s – 500s BCE), the Assyrian Empire (1300s – 600s BCE), and the Persian Empire (500s – 300s BCE).

Photo by Shirley Hall Diaz.

The empire that has had the most lasting impact on the current geography of the region was the Arab-Islamic Empire. Islam arose on the Arabian Peninsula in the 600s CE and its earliest converts began to forge an empire shortly before the death of the Prophet Mohammed. By 632, Arab Muslims controlled much of the Arabian Peninsula. By the 640s, the Empire controlled all of the Arabian Peninsula, and expanded in Egypt and Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq). By the 660s, the Empire had expanded into Persia (modern-day Iran), the Caucasus, and the modern-day territories of Afghanistan and Pakistan. Between the 660s and the 750s, the Empire expanded along the Mediterranean rim of Africa, and then across the Strait of Gibraltar into Spain, where Muslim states would remain for the next seven centuries.

The Arab-Islamic Empire typically allowed local rulers they had conquered to retain power over their territories, provided they converted to Islam and collected taxes to support the Empire. The Empire also established the region’s long-standing bond between government and religion, with Islamic rules serving as the basis for civil law. One of the Empire’s most profound legacies, of course, was the widespread diffusion of Islam and the Arabic language.

By the 900s, the Empire began to fragment into smaller states, but the region’s influence on global culture had just begun. The Islamic Golden Age (900s – 1400s) was a time of extraordinary economic, technological, and cultural development. Arab merchants became integral to the global economy, their trading sphere reaching from the Atlantic Ocean, across Africa to the Indian Ocean, and on to the edge of the Pacific. It is not a coincidence that Islam began to flourish in East Africa, the Sahel, India, Bangladesh, Malaysia, and Indonesia during the 1000s. Some of the world’s greatest libraries and universities were founded in North Africa and the Middle East during this time period, notably at Alexandria, Baghdad, Damascus, and Fez, as well as at Toledo in Muslim Spain. Golden Age scholars founded the world’s first law schools, developed the study of algebra, sociology, and economics, and are credited with developing an early version of the scientific method. The Arab-Islamic world was known for its tolerance of non-Muslims (some of its most influential scholars were Christians), and for its appreciation of foreign cultures. Much of the literature, poetry, and philosophy of ancient Greece and Rome would have been lost forever had it not been preserved in Arab libraries.

Photo by Stacie Haen-Darden.

North Africa and the Middle East’s last great empire was the Ottoman Empire. The Ottomans were a Turkish people who began to assemble their empire in Anatolia in the 1200s. In the 1400s, the Ottomans conquered the Byzantine Empire and overtook its capital, Constantinople, which they renamed Istanbul. Over the next two centuries, the Ottoman Empire would reach its height, controlling Turkey, the eastern Mediterranean, Egypt and much of the rest of North Africa, Mesopotamia, much of the Arabian Peninsula, a good deal of the Greek and Balkan Peninsulas, and all of the land that surrounded the Black and Red Seas. During this time, it was the world’s wealthiest empire, controlling a key global pivot point – nearly all the trade that flowed among Asia, Europe, and Africa passed through Ottoman lands.

At its height, however, the seeds of the Ottoman Empire’s doom were already being sown. European countries, notably Portugal, began to explore the world’s oceans, creating sea-trade routes that would eventually undercut the Ottomans’ land-trade routes. The colonization of the Americas by Spain, Portugal, Britain, and France would open up new markets that the Ottomans could not access. By the 1700s, the Industrial Revolution was making Europe the center of global economic and technological power. European empires began to chip away at Ottoman territory. The French colonized Algeria in 1830, Tunisia in 1881, and Morocco in 1912. Britain colonized Egypt in 1882, and Sudan in 1898. Italy colonized Libya in 1912. World War I would ultimately doom the Ottoman Empire. The Ottomans sided with Germany and Austria-Hungary, and were defeated. Most of the remaining Ottoman territories were seized by the victorious countries, with France colonizing Syria and Lebanon, and Britain colonizing Palestine, Iraq, and Jordan.

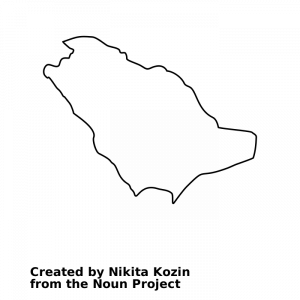

What remained of Ottoman territory would soon emerge as the Republic of Turkey, led by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, who launched a campaign of Turkish modernization and westernization. At about the same time, Sheik Ibn Saud began to consolidate tribal territories on the Arabian Peninsula to form the independent country of Saudi Arabia. The remaining areas of the Arabian Peninsula fell under British influence, including lands that would eventually become Yemen, Oman, Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates.

Most of the European colonies in North Africa and the Middle East were protectorates – a form of colonization that allowed local rulers to remain on the throne, but with European officials often dictating their domestic and foreign policy. During the colonial period, local forms of ethnic and religious government were dismantled, and communal lands were largely privatized. The end result was the concentration of wealth and political power in the hands of the ruling class at the expense of most the region’s population.

From the 1920s through the 1940s, many protectorates and colonies were granted home rule or independence, but British and French influence remained strong through the early 1940s. After World War II, the United States would emerge as the region’s most influential foreign power. The United States often supported authoritarian leaders who were sympathetic to U.S. geopolitical and economic interests. The United States was interested in preventing the expansion of communism into North Africa and the Middle East during the Cold War, and in maintaining political stability in a region that supplied much of the world’s oil. Unfortunately, the rulers backed by the United States, such as the Saudi royal family, the Shah of Iran, and numerous military dictators, provided stability at the expense of democracy, civil rights, and equal opportunity. The region’s ruling class became fabulously wealthy, and the gap between the wealthy and poor expanded dramatically. The deep-seated resentment against the United States government, still prevalent in much of the region, is largely the result of the U.S. relationship with these oppressive regimes.

Cultural Geography

Arab cultural identity and the Arabic language accounts for about 48% of the region’s population, and are dominant in North Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, and Iraq. Arabs also make up about 24% of Israel’s population. This common cultural bond, extending from Morocco to Mesopotamia, makes this a particularly unique region, although there is a good deal of cultural diversity within the Arab world.

The region’s most significant non-Arab populations include the Jews, a Hebrew-speaking people who represent 76% of Israel’s population; the Turks, a Turkish-speaking people who represent 75% of Turkey’s population; the Persians, a Farsi-speaking people who represent 61% of Iran’s population; and the Kurds, a Kurdish-speaking people who represent 15 to 20% of the populations of Iran, Iraq, and Turkey. Some significant ethnic minorities include Azeris in Iran, Berbers in northwest Africa, and South and Southeast Asians in the Persian Gulf states.

The religious geography of the region is discussed in Chapters 13 and 20.

Population Geography

North Africa and the Middle East are home to nearly 600 million people – slightly less that twice the population of the United States, or slightly less than half the population India. Three large countries – Egypt (102 million), Iran (84 million), and Turkey (84 million) – account for nearly half the region’s population. Other large countries include Algeria (44 million), Sudan (44 million), and Iraq (40 million). The table below shows the population of the region’s remaining countries, along with a U.S. state with a comparable population.

| Country | Population (in millions) | US Comparison |

|---|---|---|

| Morocco | 37 | California |

| Saudi Arabia | 35 | California |

| Yemen | 30 | Texas |

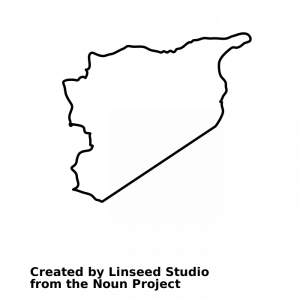

| Syria | 18 | New York |

| Israel and Palestine | 14 | Pennsylvania |

| Tunisia | 12 | Ohio |

| Jordan | 10 | Michigan |

| UAE | 10 | Michigan |

| Lebanon | 7 | Massachusetts |

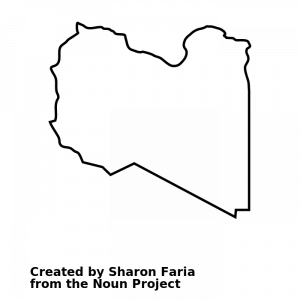

| Libya | 7 | Massachusetts |

| Oman | 5 | Alabama |

| Qatar | 3 | Arkansas |

| Bahrain | 2 | Nebraska |

| Mauritania | 5 | Alabama |

| Niger | 24 | Florida |

Birth rates in North Africa and the Middle East are considerably higher than in many other regions of the world, but declined significantly in the second half of the 20th century as the region continued to progress through the demographic transition. In 1960, the region’s total fertility rate (TFR) was about 9.0 (nine children per female). By 2000, the regional TFR had declined to 4.0. Still, the majority of the region’s countries have TFRs at or above the global average of 2.4 children per female, including Sudan (4.3), Yemen (3.7), Iraq (3.6), Palestine (3.6), Egypt (3.3), Israel (3.0), Algeria (3.0), Syria (2.8), Oman (2.8), Jordan (2.7), and Morocco (2.4). Four countries have TFRs that are below the world average, but above the replacement rate of 2.1, including Saudi Arabia (2.3), Libya (2.2), Tunisia (2.2), and Iran (2.2). Six of the region’s countries have TFRs at or below 2.1 – Kuwait (2.1), Turkey (2.1), Lebanon (2.1), Bahrain (2.0), Qatar (1.9), and the UAE (1.4).Population Growth

The strongest influences on birth rates in North Africa and the Middle East are the same as many other regions. Countries with fewer career opportunities for women, with more rural populations, with lower levels of educational achievement, and more frequent interethnic conflict tend to have higher birth rates.

Although the region’s declining birth rates are encouraging, the population of North Africa and the Middle East are likely to continue to grow for years to come. Nearly 40% of the region’s population is under the age of fifteen, so even if TFRs continue to decline, a large portion of the population will soon enter their reproductive years. This is troubling for a region where water, food, and jobs are already quite scarce.

Migration

Between 2015 and 2020, Syria lost a greater share of its residents to emigration than any other country on earth – 2.4% annually. This is certainly understandable, given the devastating civil war that has been raging there since 2011. While no other countries in the region have experienced a net migration loss nearly as extreme, just over half of them lost more migrants than they gained over the same time period, including Lebanon, Palestine, Morocco, Sudan, Yemen, Iran, Egypt, Tunisia, Libya, and Algeria. While conflict is partially responsible for this exodus – particularly in Yemen and Libya – the vast majority of emigrants from these countries are motivated by economic push factors. The lack of economic diversity has made employment difficult to find, particularly for young people with advanced educations, and millions have left the region seeking economic opportunity. Europe, the United States, Canada, and the wealthy states along the Persian Gulf are the most popular destinations.

Between 2015 and 2020, ten countries had net migration gains, although three of them did so under unfortunate circumstances. Iraq, Jordan, and Turkey had modest migration gains, but nearly all of that was the result of refugees fleeing the war in Syria. Nearly 4 million Syrians currently reside in refugee camps in the region.

Over the same period, however, a number of the region’s countries had extremely high rates of economic immigration. In fact, Bahrain led the world in net migration rate, with an annual migration gain of 3.1%. Five of Bahrain’s Persian Gulf neighbors – Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Kuwait, Qatar, and Oman also experienced extremely high rates of immigration. This continues a trend that began in the 1970s, when global oil prices soared. The native populations of many of the oil-rich Gulf states are relatively small, and as their economies expanded rapidly, they recruited large numbers of guest workers to fill the huge number of jobs that were being created. In the UAE, for example, nearly 75% of private sector workers are not native Emiratis. The largest sources of workers in the Gulf states are from Palestine, Egypt, Pakistan, India, and Indonesia.

Israel also has a positive net migration rate, and has for a number of years. Not only is it the wealthiest country in the region, but it strongly encourages immigration from Jewish communities around the world. It’s highest rates of immigration occurred shortly after World War II, when Jewish survivors of the Holocaust fled Europe for the nascent country. In 1950, Israel adopted the Law of Return, which allows any Jew to apply for citizenship in Israel. Another wave of immigrants arrived in the 1990s, when 700,000 Jews immigrated from the former Soviet Union after its collapse, and when 25,000 Ethiopian Jews arrived, fleeing a civil war.

North Africa and the Middle East has also experienced a good deal of movement within countries in the form of rural-to-urban migration. Well into the 20th century, the vast majority of the region’s population lived in agricultural villages, but as economic opportunities have declined in rural areas, urbanization rates have increased significantly. Today, the region is nearly two-thirds urban, and every country except Sudan, Egypt, and Yemen has a majority-urban population.

Political Geography: Governments

Colonization and Independence

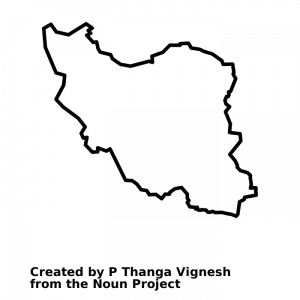

A few countries in North Africa and the Middle East avoided European colonization, notably Turkey, which emerged from the ruins of the Ottoman Empire in 1918, and Saudi Arabia, which was unified in 1932. Iran was never formally colonized, although Western influence in the country was strong from the 1800s to the 1970s. Likewise, Oman was never colonized, but was subject to significant British influence until the 1970s.

The rest of the region was colonized by one European empire or another in the 1800s or early 1900s. As mentioned above, in some cases local rulers were allowed to retain nominal or partial control over their countries, but were largely subordinate to European power. France colonized Lebanon, Syria, Morocco, Tunisia, and Algeria, while Britain colonized Sudan, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Yemen, Bahrain, Qatar, and the UAE. Libya was a colony of Italy, and would be administered for a time by the United Nations after the Italian surrender in World War II.

The colonies in this region gained their independence over a long period of time in the 20th century. Iraq gained independence in the 1930s; Lebanon, Syria, Jordan in the 1940s; Morocco, Tunisia, Sudan, and Libya in the 1950s; Algeria, Kuwait, and Yemen in the 1960s; and Bahrain, Qatar, and the UAE in the 1970s.

Democracy & Authoritarianism

North Africa and the Middle East is the world’s least democratic region. Only one country, Israel, can be considered a full democracy, with a fair, multi-party elections, a free press, and a respect for basic civil rights. Still, even Israel is not without its problems. Several high-profile corruption scandals have rocked the country in recent years, and Israel’s Jewish majority enjoys far more political power than religious and ethnic minorities.

Turkey, Tunisia, Morocco, Kuwait, and Lebanon are partial democracies – featuring democratic institutions, free elections, and basic civil freedoms, but also featuring significant suppression of the political opposition and/or rampant corruption. Turkey held its first free elections in 1950, but experienced military coups in 1960, 1971, 1980, and 1997. The current government, led by President Recep Erdogan, has increasingly cracked down on dissent. Since he came to power in 2014, thousands of people of have been arrested for “insulting the president,” and press freedoms have been curbed. A failed military coup in 2016 gave Erdogan further license to silence dissent, and thousands of soldiers, judges, teachers, and students were arrested. After years of one-party rule, Tunisia emerged as a democracy in 2011, but in recent years its government has taken an increasingly authoritarian turn. Morocco and Kuwait hold free parliamentary elections, but parliament shares power with the royal family in each country. The citizens of Lebanon enjoy some basic political freedoms, but their government has a history of delaying elections, demonstrates a lack of respect for the rule of law, and suffers from rampant corruption.

All of the region’s remaining countries are ruled by authoritarian governments, where elections are absent or fraudulent, political opposition is regularly suppressed, and basic personal freedoms are not guaranteed. Algeria has been ruled almost exclusively by a military-backed party since independence, and Syria has been a one-party state since 1970. Libya was a dictatorship from 1969 to 2011, and has since devolved into civil war. Egypt was ruled by a military government from 1952 to 201l. After a brief flirtation with democracy, military rule returned to Egypt in 2013. After decades of military rule, Iraq began to hold elections since 2005, but the elections are deeply flawed, and authoritarian rule largely remains in place.

A number of the region’s countries are monarchies, some with local and parliamentary elections, but where ultimate power still rests with royal families. In addition to semi-democratic Morocco and Kuwait, the region’s monarchies include Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, the UAE, and Oman.

Many countries in North Africa and the Middle East are home to Islamist political movements that hope to establish theocracies – governments that are ruled by religious leaders according to Islamic law. Over the last few decades, Islamist revolutions occurred in Syria, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Egypt, Algeria, Iraq, and Morocco, but all of them failed. Only one country has experienced an Islamist revolution that managed to successfully install a theocracy. In 1979, a disparate group of revolutionaries overthrew the pro-Western government of Iran, and Islamist forces were ultimately able to seize control of the country. A group of conservative Shia Muslim clerics – called the Supreme Council – assumed control of the country’s courts and military. Iran does have an elected civilian government that handles the day-to-day functions of the country, but the Supreme Council determines which candidates are eligible to run for office, and only approve candidates that share their views. Iran’s government is not tolerant of political dissent, regularly arresting and often executing its critics.

In 2011, in an event that became known as the Arab Spring, pro-democracy demonstrations erupted across North Africa and the Middle East. The movement began in Tunisia, where protests against government corruption forced President Ben Ali to leave office after twenty-five years in power. Soon, similar demonstrations were taking place across the Arab World, with protestors decrying a lack of democracy, government corruption, a lack of freedom of speech, entrenched poverty, and the widening gap between the wealthy and poor. At first, these protests yielded positive results. Throughout the region, long-standing strongmen were forced from office, municipal democracy was expanded, and new elections and reforms were promised. Unfortunately, many of these promises proved to be empty. Worse still, civil wars erupted in Syria, Yemen, and Libya, all of which have now been raging for more than a decade.

Political Geography: Conflicts

In this section, we will examine some of North Africa and the Middle East's ongoing conflicts (except for conflicts in Palestine, Israel, and Iraq, which are discussed separately in Chapters 15 and 22) as well as some of the major political powers in the region.

Libya

In 2011, Arab Spring protests against long-time Libyan dictator Muammar Qadhafi escalated into a civil war. Revolutionaries were able to capture the capital, and assassinated Qadhafi as he fled. Over the next three years, Libya fragmented into numerous competing factions, including forces that had been loyal to the former dictator and those who deposed him, but also various tribal and Islamist factions, including forces loyal to the Islamic State (see below). Since 2014, Libya has been divided into two major factions. A government based in Tobruk controls much of Libya’s east and south. It is comprised mainly of former Qadhafi loyalists, and is supported by Egypt, Russia, and the UAE. Another government, based in Tripoli, controls Libya’s northwest, consists mainly of anti-Qadhafi forces and various tribal militias, and is supported by the United States, the European Union, Turkey, and Jordan. More than 100,000 people have been killed since fighting began in 2011.

Photo by maartenF for Flickr.

Yemen

In 2012, Arab Spring protests led to the ouster of Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh, who had been in office for more than three decades. He was succeeded by his vice president, Abdrabbuh Manur Hadi. Saleh, who had not left office willingly, soon threw his support behind the Houthi insurgency in an attempt to regain control of the country (this relationship would eventually sour, and Saleh was executed by the Houthis). Since then, Yemen has devolved into a multi-faction civil war. The official government faction consists of Sunni Muslims who advocate a secular form of government, and who were loyal to President Hadi. It is primarily led by Sunni military officials, and is supported by Saudi Arabia, which has carried out a violent bombing campaign on its behalf. The governments main rivals are the Houthis, a Shia faction who took their name from a northern tribe who initially launched the insurgency. It is led by Shia militias and military officers, and is supported by Iran. Other factions included combatants loyal to al-Qaeda or the Islamic State, and numerous tribal factions that want to secede from Yemen altogether. More than 377,000 people have been killed in the fighting.

Syria

In 2011, the regime of Bashir Assad responded violently to Arab Spring protests, and the country plunged into a civil war. The Assad government suffered numerous setbacks at the start of the war, but has been steadily regaining control of lost territory for the last several years. Its strongholds are mainly in the western part of the country, and its territories include the majority of Syria’s population. Assad loyalists primarily consist of Shia and Alawite Muslims, and are supported by Iran, Lebanon’s Hezbollah militia (see below), and Russia. Over the course of the war, the Assad government has been accused of numerous human rights violations and war crimes, including the use of chemical weapons against civilian targets.

The main Syrian opposition controls sections of the north and south, although their territories have diminished in recent years. It consists of various moderate Sunni factions opposed to the Assad regime, and is supported by most western countries, such as France and the United States, as well as Israel and Saudi Arabia.

The Islamic State (see below) has also been active in this war. A radical Sunni militia that once attempted to establish a new country in the Middle East, the Islamic State no longer controls significant territory in Syria, but it remains an underground presence in the country.

Finally, Kurdish militias control an increasing amount of Syrian territory, particularly in the north. These militias were mainly concerned with protecting Kurdish civilians, and proved to be the most effective force in defeating the Islamic State. The Kurds have since gained support from the United States, Russia, and the Assad regime. The Kurds are pursuing a potential autonomous region within a post-war Syria, an idea that has met with fierce objections from Turkey.

Since the beginning of the war, more than 350,000 people have been killed, and millions have been displaced from their homes.

The Islamic State

The Islamic State (also known as ISIL, ISIS, or Daesh) is a militant Sunni extremist group that once controlled vast sections of Syria and Iraq. This group coalesced around the Sunni insurgency during the waning days of the Iraq War (see Chapter 22), and seized control over remote areas of western Iraq that were not fully under government control. After 2011, the Islamic State was able to expand into Syria during that country’s civil war. The group viciously targeted non-Sunni populations such as Shias, Yazidis, and Christians, and has also targeted Sunnis who they consider to be too moderate. The Islamic State has been accused by the United Nations of widespread human rights violations.

The Islamic State has ambitions to create a global caliphate, and numerous radical Islamist groups in Algeria, Libya, Egypt, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Afghanistan, and Pakistan have pledged allegiance to the group. The Islamic State, and groups loyal to it, have carried out numerous attacks against mosques, hotels, resorts, and other civilian targets in North Africa and the Middle East, and has been linked to terrorist attacks in Europe, Central Asia, South Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa as well. The group’s actions have been so horrendous that they’ve made enemies of practically every major political power in the region. The Islamic State has lost formal control over all of its territory due to withering attacks by the Iraqi government, Iraqi Shia militias, the Syrian government, the United States, and the Kurds, among others. Nevertheless, the Islamic State still appears to be organized and capable of carrying out terrorist attacks.

The United States

For more than seven decades, the United States has been the most active foreign power in North Africa and the Middle East. It is a longtime ally of Israel, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia. In 2003, the U.S. invaded Iraq and installed a new government, which it heavily subsidizes. The U.S. has supported Kurdish militias and Syrian rebels in their fight against the Assad regime and the Islamic State, and supports Yemen’s government in that country’s civil war. The U.S. has a generally positive relationship with the region’s Sunni Arab states, but has generally favored Israel’s interests over those of the Sunni Arab Palestinians. And, although it supports Kurdish political aspirations in Syria and Iraq, it has condemned Kurdish separatism in Turkey. The U.S. has supported Iraqi Shia militias in their battle against the Islamic State, but has a generally adversarial relationship with Lebanon’s Shia Hezbollah militia and the Shia government of Iran.

Iran

Iran is the largest Shia country in North Africa and the Middle East, and has recently assumed a more assertive role in the region, seeing itself as the primary defender of non-Sunni populations. Iran supports the Assad regime in Syria, the Shia Houthi rebels in Yemen, and has long supported the Shia Hezbollah militia in Lebanon. Iran long viewed Iraq as an adversary, but has been working in recent years to build a closer relationship with that country’s Shia majority.

Iran frequently finds itself at odds with Saudi Arabia (see below), but its greatest traditional adversaries have been Israel and the United States. Iran refuses to recognize the legitimacy of Israel, and has repeatedly called for the country’s destruction. Iran’s ill will toward the United States dates back to Operation Ajax, a U.S.-orchestrated military coup that’s been largely forgotten in the United States, but certainly not in Iran. In 1953, the United States’ Central Intelligence Agency, in cooperation with British Intelligence and members of Iran’s military, overthrew the democratically-elected president of Iran, and placed control of the country in the hands of its monarch, known as the Shah. The Shah was pro-Western and anti-communist, which suited U.S. interests, but he was deeply unpopular with the majority of Iranian citizens, and grew more unpopular with each passing year. In 1979, the Shah was ousted and an Islamist government took power. In the wake of the revolution, fifty-two U.S. diplomats and civilians were held hostage in Tehran by Islamist militants for more than 400 days. Since then, the United States has played a prominent role in isolating Iran diplomatically and economically from the rest of the world. Iran responded by vilifying the United States at every opportunity, with the country’s leaders frequently referring the U.S. as the “Great Satan.”

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia is North Africa and the Middle East’s most politically and economically prominent Arab state. It has long been a leading source of military aid and economic investments to the region’s Sunni Arab countries, including Egypt.

Saudi Arabia is a longtime ally of the United States, although it has been, at times, an uncomfortable relationship. The United States has long been critical of Saudi Arabia’s human rights record. Many key founders of the terrorist organization al-Qaeda, including Osama bin Laden, were Saudi, as were the majority of the hijackers who carried out terrorist attacks against the United States on September 11th, 2001. And Saudi Arabia, a conservative Muslim country, has long been wary of America’s cultural influence.

Nevertheless, the relationship is vital for both countries. The United States supplies Saudi Arabia with most of its military hardware, and Saudi Arabia is key to U.S. military activity in the region – neither of the U.S. invasions of Iraq would have been possible without the aid of Saudi Arabia. The Saudi and American governments also have a shared interest in crushing Islamist extremist movements such as the Islamic State. Moreover, the two countries are deeply invested in one another economically.

The Americans and Saudis also have a significant shared adversary. Saudi Arabia views Iran as its greatest existential threat. Iran’s population is more than twice that of Saudi Arabia, but the Saudis have long held a huge economic advantage over the Iranians. However, if the world begins to ween itself from dependence on oil, the backbone of the Saudi Arabia’s economy, then the balance of power may shift. Iran and Saudi Arabia have backed opposing sides in civil conflicts in Lebanon, Yemen, and Syria, in what many see as a brewing regional Cold War, with Saudi Arabia backing Sunni interests and Iran backing Shia and other non-Sunni interests.

Lebanon

Lebanon is a predominantly Arab country, but its population is divided almost evenly into three major religious groups – about a third are Christian, a third Sunni Muslim, and a third Shia Muslim. For many years, it was a stable and prosperous country where power was shared peacefully among the three major religious groups. In the 1970s and 1980s, however, violent incidents among these three groups escalated into a civil war that devastated the country. The last three decades have been somewhat peaceful, but the three groups still find themselves divided over conflicts around the region. Lebanon’s Christians tend to be supportive of, and are supported by, Israel and the major western powers. Lebanon’s Sunni’s are generally supportive of the Palestinians and other Sunni Arab populations. Lebanon’s Shia population are generally supportive of Iran and Syria’s Assad regime.

Complicating matters is the presence of Hezbollah, a Shia militia that was formed during the civil war, and which is still armed. Hezbollah is arguably more powerful than the Lebanese military and acts autonomously from it. It has carried out attacks on Israel, and is active in the Syrian civil war in support of the Assad regime.

Israel

Israel has numerous major adversaries in the region, including the Palestinians, Iran, the Syrian government, and Lebanon’s Hezbollah. Israel’s relationship with the region’s Sunni Arab states is complicated. Most Arab states did not initially recognize Israel’s right to exist, and most have supported the Palestinians in their conflicts with Israel. During the 20th century, Israel engaged in conflict with many Arab powers, including Jordan, Egypt, Lebanon, Syria, and Saudi Arabia.

In recent years, however, Israel has enjoyed a stable, if not necessarily friendly, peace with most of the region’s Sunni Arab states. Both Israel and the Sunni states are largely aligned with the United States, and are united in their opposition to Syria’s Assad regime, the Islamic State, and Iran. In 1979, Egypt became the first Arab state to recognize Israel’s right to exist, followed by Jordan in 1994. In 2020, Israel established diplomatic relationships with Morocco, Sudan, Bahrain, and the UAE.

Turkey

Turkey is a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), a military alliance that includes the United States, Canada, and many of the major powers of Europe, such as Germany, France, Italy, Britain, and Poland. It had traditionally been Europe and the United States’ closest Muslim ally in North Africa and the Middle East.

Turkey is populated mostly by Sunni Muslims, but the Turks are not Arabs, and the country has long been the most westernized country in the region. This complicates its relationship with the region’s Shia, Arab, and conservative populations. But Turkey’s greatest geopolitical concern is Kurdistan. For many years, Turkey has fought sporadic conflicts with Kurdish separatists in the eastern part of the country.

Kurdistan

The Kurds are a prime example of a stateless nation. There are 28 million Kurds living in the Middle East, a population equal to that of Syria and Jordan combined. However, in the wake of the Ottoman Empire’s collapse, Kurdistan was unable to secure independence. A non-Arab and primarily Sunni population, the Kurds occupy a huge homeland spanning parts of Iraq, Turkey, Syria, and Iran. Although the Kurds have achieved considerable autonomy in Iraq and Syria, Kurdistan is still not a unified or independent state.

The Kurds had long been distrusted by most of the important powers in the region. As mentioned above, Turkey has been fighting Kurdish separatism for years. Iran has a largely adversarial relationship with Sunni populations, and Arab states are generally distrustful of the region’s non-Arab populations. During the Cold War, the United States viewed the Kurds as a potential threat to the stability of its anti-communist allies in Turkey and Iraq.

The Kurds quickly gained a number of allies over the last decade. The Kurdish peshmerga (Kurdish militias – literally “those who face death”) were instrumental in the destruction of the Islamic State, and received support from Iran, Saudi Arabia, Russia, and the United States – the only group in the region to be supported by all four of these countries. This has created grave concerns for the Turks, who fear that the Kurds’ sudden prominence will allow them to press for autonomy or even independence in eastern Turkey.

Economic Geography

Overall standards of living in North Africa and the Middle East fall close to the world average. The region’s countries are, in general, much better off economically than their neighbors in Sub-Saharan Africa, but not nearly as wealthy as their neighbors in Europe.

Israel has the region’s highest standards of living by a wide margin, ranking alongside some of the world’s wealthiest countries, such as Japan and the United States. Israel’s primary industries include high-tech manufactured goods, cut diamonds, pharmaceuticals, and tourism.

Turkey, along with five states on the Arabian Peninsula – Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, and the UAE – are in an economic tier below Israel, but with relatively high standards of living, on par with some of Europe’s mid-income countries like Portugal and Poland. The five Gulf States accumulated wealth from their vast reserves of petroleum, and all have made attempts to diversify their economies with tourism, finance, manufacturing, transportation, and telecommunications, although oil prices still largely dictate the health of their economies. Turkey has long been a major agricultural producer, and has had some success in developing other forms of revenue through banking, transportation, tourism, and manufacturing.

Many of the rest of the region’s countries have standards of living similar to those of Mexico and Brazil – not particularly wealthy, nor particularly poor. Lebanon was long a financial and shipping hub for the region, and has significant economic potential, but is still recovering from its civil war. Tourism is an important source of revenue for Lebanon, Egypt, Tunisia, and Morocco, with the latter three countries also having some success in manufacturing. Much of the rest of the region is primarily dependent on the export of raw materials. Oil, natural gas, and minerals are the leading exports of Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Algeria, and Libya.

Yemen has long been the poorest country in the region, and one of the poorest countries on earth, with standards of living resembling those of much of Sub-Saharan Africa. Its meager economy is based on limited oil reserves and agricultural exports. Syria, once a relatively prosperous oil-exporting country, has seen its standards of living tumble dramatically as result of its protracted civil war.

Did you know?

Persian mathematician, Omar Khayyam, developed the foundations of algebraic geometry.

Cited and additional bibliography:

Birkhofer, Jennifer. Rock bridge at Jebel Kharaz in the Wadi Rum Protected Area in Jordan. April 2022.

Diaz, Shirley Hall. Pyramids at Giza, Egypt. Photo. 2022.

Haen-Darden, Stacie. Turkish mosque. Photo.

maartenF. Yemen. February 21, 2009. Photo. https://www.flickr.com/photos/33945754@N07/3298077542/. Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

Savage, Cynthia Gronewold. Ruins at Ephesus, Turkey. Photo, 2022.