42 SE Asia: Historical Geography I – SE Asia and the Cold War

The Cold War was a four-decade struggle between the United States and Soviet Union, with the Soviets attempting to spread communism throughout the globe, and the U.S. and its capitalist allies attempting to contain it. Both countries backed insurgencies and counterinsurgencies in dozens of countries around the world, but few regions saw more prolonged conflicts than Southeast Asia. With the backing of the United States, Thailand’s government successfully defeated a communist insurgency that lasted from 1965 to 1980. The British successfully defeated a similar insurgency in colonial Malaysia in the 1950s. Burma, although officially a socialist country and neutral during the Cold War, fought a communist insurgency with covert American support for nearly four decades. One of the deadliest events of the Cold War occurred in Indonesia. General Suharto, a high-ranking military official, launched a purge of communists in 1967 with support from the American Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Communists, or those simply suspected of having leftist sympathies, were detained and tortured. It is estimated that nearly a million Indonesians were executed by government forces. Suharto would seize control of the country and serve as its dictator, with U.S. support, for three decades. Remarkably, this was not the bloodiest chapter in Southeast Asia’s Cold War history. The most intense fighting, and stunning brutality, took place in former French Indochina – in the countries of Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia.

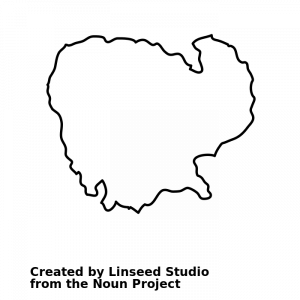

Vietnam

Vietnam’s communist insurgency, led by Ho Chi Minh, began as a resistance movement against Japanese occupation during World War II. After the war, France recolonized Vietnam, and soon found themselves fighting the communists as well. After a stunning defeat at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1954, France was forced to negotiate a surrender to Ho Chi Minh’s forces. The resulting Geneva Accords established the 17th parallel of latitude as the dividing line between the communists, who controlled the northern part of the country, and the French, who still occupied the south. Two separate independent states were established. North Vietnam, with its capital at Hanoi, was a communist state aligned with China and the Soviet Union. South Vietnam, with its capital at Saigon, was a capitalist state aligned with the United States. The Geneva Accords allowed citizens of either country to migrate across the 17th parallel. A large number of northern capitalists relocated to Saigon, and some communists relocated north, but a number of communist operatives remained in South Vietnam.

South Vietnam’s government soon faced opposition from not only North Vietnam, but also from those communists still living in the south. Realizing that South Vietnam’s government had only tenuous control over their own country, the United States began sending military equipment to the south, along with advisors to train South Vietnam’s military and security forces. South Vietnam’s leaders proved to be corrupt and incompetent, ignoring the needs of the citizens, who began to turn against their government. In the late 1950s, a communist resistance force in South Vietnam, known as the Viet Cong, began to level attacks against the South Vietnamese army, security forces, and other government personnel. The Viet Cong was a guerrilla force, carrying out attacks and fighting pitch battles before blending back into the civilian population. It was almost impossible to tell who was a communist militant and who was a noncombatant.

By the early 1960s, it became apparent to the United States that the South Vietnamese government was unprepared to defeat the Viet Cong. More American military advisors were there, along with more sophisticated weaponry. North Vietnam, inspired by the Viet Cong’s successes, began to funnel both weapons and troops to South Vietnam. Soon, communist forces were targeting U.S. military bases. The United States responded with a sustained aerial bombing campaign of North Vietnam, but that did little to improve the situation in the south.

By 1965, the fall of South Vietnam’s government appeared to be imminent. For the first time, the United States began to commit regular combat troops to the country, sending a force 200,000 personnel over the next year. The U.S. launched a furious assault against the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army, utilizing heavy artillery, helicopter assaults, aerial bombing, napalm, and a chemical defoliant known as Agent Orange to deprive the Viet Cong of jungle cover.

It was unlike any war the United States had ever fought. Success was measured not in ground gained. More often than not, the United States would attack an enemy position, secure it, and then abandon it, only to have it reoccupied by communist forces. The U.S. was fighting a war of attrition, measuring their success by body counts, totaling up the number of enemy fighters killed in battle. The prevailing theory was that the U.S.’s superior fire power would eventually inflict more casualties on the enemy than it could replace.

The United States did indeed inflict enormous damage on the communist forces, but U.S. casualties began to climb as well. Oftentimes the greatest number of fatalities were not combatants, but Vietnamese civilians, including many children, who were caught in the crossfire. By 1967, the American public’s support for the war was sagging. Many Americans objected to the war on moral grounds, unsure why the United States was killing Vietnamese civilians to prop up a corrupt and unpopular regime in South Vietnam. Many more were troubled by the mounting U.S. casualties in a war that seemed to have no end in sight. The U.S. government, however, was unwilling to abandon a war that had already cost so much, both in money and in lives, and was soon pouring even more troops into the country. At the war’s peak, there would be more than half a million American troops in Vietnam.

By 1969, however, it became apparent to U.S. leaders that the war was unwinnable. That year, the United States began a phased withdrawal of troops from Vietnam, and the final American troops left the country in 1973. Saigon would fall in 1975, and the country was unified under communist rule. The Vietnam War proved to be one of the deadliest episodes of the Cold War. More than 58,000 American military personnel were killed in the conflict, along with 250,000 South Vietnamese troops, and more than a million communist fighters. But the greatest casualties were inflicted on noncombatants. At the war’s end, more than two million civilians were dead.

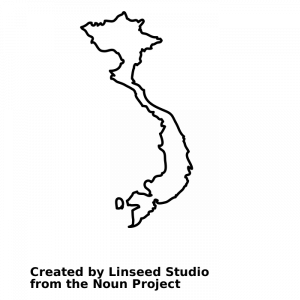

Laos

By 1964, Laos had experienced more than its fair share of troubles. Poor, rugged, and landlocked, this small country had been colonized by France and then occupied by Japan. It gained independence in 1954, but was soon plunged into a civil war as government forces battled communist rebels. But perhaps its greatest liability was having Vietnam as a neighbor.

By 1964, Laos had experienced more than its fair share of troubles. Poor, rugged, and landlocked, this small country had been colonized by France and then occupied by Japan. It gained independence in 1954, but was soon plunged into a civil war as government forces battled communist rebels. But perhaps its greatest liability was having Vietnam as a neighbor.

As the war in Vietnam intensified, the North Vietnamese government began to open supply routes through Laos and Cambodia to funnel weapons to the Viet Cong in South Vietnam. Collectively known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail, these supply routes became a prime target for American military strategists.

Although it was technically illegal, and unacknowledged by the U.S. government, the CIA ordered more than 230,000 aerial bombing raids into Laos between 1964 and 1973. That’s the equivalent of a bombing run every nine minutes, twenty-four hours a day, for nine years. American planes dropped more than two million tons of bombs on Laos, more than all of the bombs dropped by all of the combatants during World War II. These bombing raids, coupled with the internal civil war, killed more than 200,000 people, or roughly 10% of Laos’s population. The raids ended in 1973, and the civil war ended with a communist victory in 1975, but the violence did not end there. It is estimated that 30% of the bombs dropped by the United States failed to explode on impact. Since 1975, nearly 20,000 civilians in Laos have been killed by bombs that detonated years after they were dropped. The United States has pledged millions of dollars for a program to find and remove the unexploded ordinance, but it is estimated that only 1% of it has been successfully cleared.

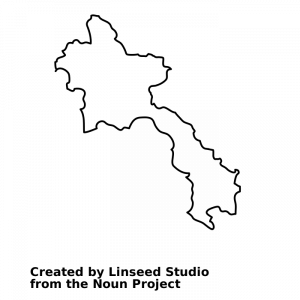

Cambodia

In the 1960s, the North Vietnamese Army and the Viet Cong infiltrated eastern Cambodia, using the country as a launching pad for attacks in South Vietnam. This emboldened Cambodian communists, who formed an insurgent group known as the Khmer Rouge. Led by Pol Pot, the insurgency made few initial gains, but the withdrawal of American troops from Southeast Asia provided a boost to their campaign, and they seized control of Cambodia in 1975.

Pol Pot believed that communism could only be achieved in a rural, agricultural, ideologically pure society. Declaring 1975 “Year Zero,” the Khmer Rouge set out on an unbelievably destructive campaign to create their imagined utopia. Factories, businesses, and banks were destroyed. Money, private property, education, and religion were abolished. The country’s intellectual elite were targeted for elimination. Hundreds of thousands of teachers, lawyers, doctors, scholars, and clergy were executed, along with anyone who spoke a foreign language, and even those who simply wore eyeglasses. Parents were separated from children and wives from husbands to ensure supreme loyalty to the Khmer Rouge. Cities were abandoned. Cambodia’s capital city, Phnom Penh, had a million residents in 1975. The following year, only 40,000 residents remained.

Survivors were marched to the countryside and resettled in villages that lacked adequate food, tools, and medical care. Hundreds of thousands died of starvation or diseases before the first harvest. Anyone who resisted was executed on the spot. The Khmer Rouge was finally driven from power when Vietnam invaded and occupied the country in 1979. Pol Pot fled into hiding and died years later, never having faced a trial. Ultimately, the Khmer Rouge were responsible for the deaths of 2.5 million Cambodians – about a third of the country’s population.

Did you know?

Cited and additional bibliography:

How Giant African Rats Are Helping Uncover Deadly Land Mines in Cambodia. 2019. www.youtube.com, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hxY3aEsesss.