54 Europe: Political Geography I – Balkanization and Separatism

Separatism, in political geography, refers to an attempt by a region of a country to separate from that country and gain independence. A related term is Balkanization, which describes any situation where one country dissolves into more than one country. The Cold War ended with the Balkanization of the Soviet Union, in which one country dissolved into fifteen countries. Two other countries dissolved at the end of the Cold War – Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia.

Both countries had formed at about the same time, and for similar reasons. The Czechs and Slovaks have different cultures, identities, and languages, but they also have a lot in common. Both nations are Slavic and historically Catholic. Both had been part of Austria-Hungary. The two nations formed a union in 1918 as the result of a sort of “safety in numbers” mentality. Surrounded by larger, more powerful states, the Czechs and Slovaks figured that by unifying they would be better equipped to resist foreign domination. Yugoslavia was formed in the same year, when a number of small southern Slavic nations (Yugoslavia means “Land of the Southern Slavs”) unified out of a similar “safety in numbers” motivation.

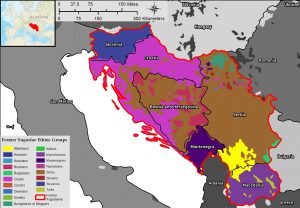

The Czechs and Slovaks divided peacefully in 1993 – so peacefully, in fact, that the dissolution was referred to as the “Velvet Divorce.” Things didn’t go so smoothly in Yugoslavia. In 1991 and 1992, four countries declared independence from Yugoslavia – Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia, and Macedonia. Serbia dominated much of what was left of Yugoslavia (and, in fact, kept the name “Yugoslavia” for a few years). What followed was Europe’s bloodiest conflict since World War II. The term “ethnic cleansing” was coined in the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s, as these newly separate states sought to “cleanse” their countries of minorities. Those who resisted were often killed. Nowhere was the fighting fiercer than in Bosnia. The Muslim Bosniaks held a slim majority in the new country, but there were (and still are) large Serb and Croat minorities in Bosnia. All three groups fought for political and territorial control, with Croatia and Serbia backing their ethnic brethren in the civil war.

The fighting continued in different areas for about a decade, leaving more than 140,000 dead. In 2006, Montenegro voted to separate from Serbia, becoming the sixth country to emerge from Yugoslavia. Kosovo, an Albanian-dominated enclave in Serbia, declared independence in 2008, although its independence is not recognized by many countries in the international community, including, of course, Serbia.

The fragmentation of the European political map might not have ended. There are a few areas in Europe that have discussed the possibility of future independence.

The most likely candidate is Scotland. For several centuries, Scotland has been united with England, Wales, and Northern Ireland in what is officially known as the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (the “UK,” or “Britain” for short). Still, the Scots have long maintained a strong separate national identity. Calls for Scottish independence intensified in the 1980s after Margaret Thatcher was elected Prime Minister of Britain. Scotland is, for the most part, a very politically liberal part of Britain, and the conservative Thatcher was not popular there. In 1997, Scotland established its own parliament. It still sends representatives to the British parliament in London, but the Scottish parliament has control over many of its own domestic affairs. In 2014, Scottish voters took part in a national referendum seeking full independence. Polls showed that a number of Scots liked the idea of independence, but felt that there were too many questions about how Scotland and the rest of the UK would divide the country’s resources and liabilities. In spite of support by the man in the photo , the referendum was defeated 55% to 45%.

After Britain’s recent exit from the European Union, however, there have been renewed calls for independence, since Scottish voters overwhelmingly voted to remain part of the EU. Recent polls show that the majority of Scots now favor independence. It is possible, even probable, that Scotland will gain independence sometime in the next few years.

The second-most likely country to gain independence in Europe is Catalonia, a region in northeastern Spain centered on the city of Barcelona. Catalonia has, in the past, been free from Spanish rule and, when it hasn’t been, it has often enjoyed a good deal of autonomy. As a result, Catalonia has always had a unique and separate identity from Spain, and even has its own unique dialect of Spanish. Many Catalonians favor independence based on these cultural and historical factors alone, but economics plays a role as well. Barcelona has long been the economic dynamo of Spain, and many in the city feel that the rest of Spain is essentially economic dead weight.

In 2017, the Catalonian provincial government held an independence referendum, which passed, leading the Catalonian parliament to declare independence. Spain’s government declared the referendum illegal (and, in the eyes of most neutral legal experts, it was). At the moment, there is no clear path forward for Catalonian independence, but there is clearly support for it.

There have been similar rumblings in northern Italy. Like Catalonia, northern Italian regions like Lombardy are the economic engines of their country, and feel limited by political corruption and economic stagnation in the rest of Italy. At this point, a genuine move for independence by northern Italy seems unlikely, but not impossible. Residents in Flanders (northern Belgium) have had similar discussions, but, similarly, independence does not seem imminent. Many residents in the Basque Country in northern Spain, and also of the French island of Corsica have made more strident calls for independence, but is unlikely that either region possesses the economic or political clout to achieve such a thing.

Did You Know?

Bosniaks, Serbs, and Croatians all speak the same language, and have a shared cultural history. The primary difference among them is religion – most Bosniaks are Muslim, most Serbs are Orthodox, and most Croats are Catholic.

The Czech Republic has adopted a shorter version for its country name – Czechia. This sort of thing is not unusual. The People’s Republic of China is generally simply called China, after all. Even so, the BBC suggests that the new name was added primarily because it fit better on sports jerseys.

For a nifty GIF of the history of Balkanization, go to http://wordsmith.org/words/images/balkanize_large.gif

Cited and additional bibliography:

Goehring, David. n.d. Balkanization. Accessed June 6, 2020. https://tinyurl.com/balkanization2. Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0).

Knight, Garry. 2018. 2014 Scottish Vote for Independence. https://tinyurl.com/yestoscotland. Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0).

McGinty, James. 2020. “Ethnic Groups of the Former Yugoslavia.” College of DuPage. College of DuPage GIS Class. Instructor Joseph Adduci.

samuel. 2018. Skalica, Slovakia. https://tinyurl.com/skalica. Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).